In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that common polygenic diseases generally do not result from accumulated defects in a single pathway but, rather, present as complex interactions among multiple environmental and inherited factors. Nowhere is this more obvious than in diabetes mellitus, which is classified into at least two groups, type 1 and type 2 (T2DM), that share hyperglycemia but differ in the initiating primary immune destruction of the β-cells or insulin resistance, respectively. Although much literature has emphasized the dissimilarities in the progression of β-cell failure in type 1 diabetes mellitus vs. T2DM, only recently have investigators focused on how the peripheral metabolic profile of T2DM differs from that predicted to be the consequence of an insulin deficiency state (i.e., simple global “insulin resistance”). As a result of these studies, the idea has emerged that the “insulin-resistant” liver, for example, remains sensitive to action of the hormone on lipid metabolism while developing resistance to the control of glucose metabolism, a state that has been termed “selective insulin resistance” (1). One consequence of this revised model has been an emphasis on examining downstream signaling pathways as possible sites of insulin insensitivity as well as potential targets for therapeutic intervention (2). In PNAS, Owen et al. (3) describe a unique “branch point” in the pathway by which insulin works in concert with nutritional signals to regulate hepatic lipid synthesis positively.

A characteristic abnormal pattern of circulating lipids and triglyceride accumulation in the liver are hallmarks of insulin-resistant states, such as obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and T2DM. In principle, the excess amounts of liver and plasma triglycerides could result from increased rates of synthesis or decreased clearance. Liver triglyceride is synthesized by the esterification of glycerol phosphate to fatty acids either taken up from the bloodstream or newly synthesized, the latter as a result of de novo lipogenesis (DNL). Two transcription factors coordinate the expression of genes encoding lipogeneic enzymes: carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein 1 (ChREBP1), which is regulated by metabolites of glucose, and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), whose activity is enhanced by insulin and amino acids working in concert through the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling complex (4,5). Regulation of SREBP-1c activity is particularly complex, however. In the basal state, it resides as an integral membrane protein in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in association with insulin-induced gene (Insig) protein (6). In times of high DNL, there is an increase in expression of the gene encoding the SREBP-1c precursor. In addition, the precursor is escorted by SREBP-1c activating protein (Scap) out of the ER and into the Golgi complex, where it can be proteolytically processed to the mature, transcriptionally active form (7). Although the regulated intracellular trafficking of the paralog SREBP-2, which is involved primarily in cholesterol metabolism, is understood in some detail, the pathway by which insulin regulates processing of SREBP-1c has been largely unknown until recently; in PNAS, Owen et al. (3) define perhaps the most distal signaling event so far identified in the regulation of SREBP-1c processing.

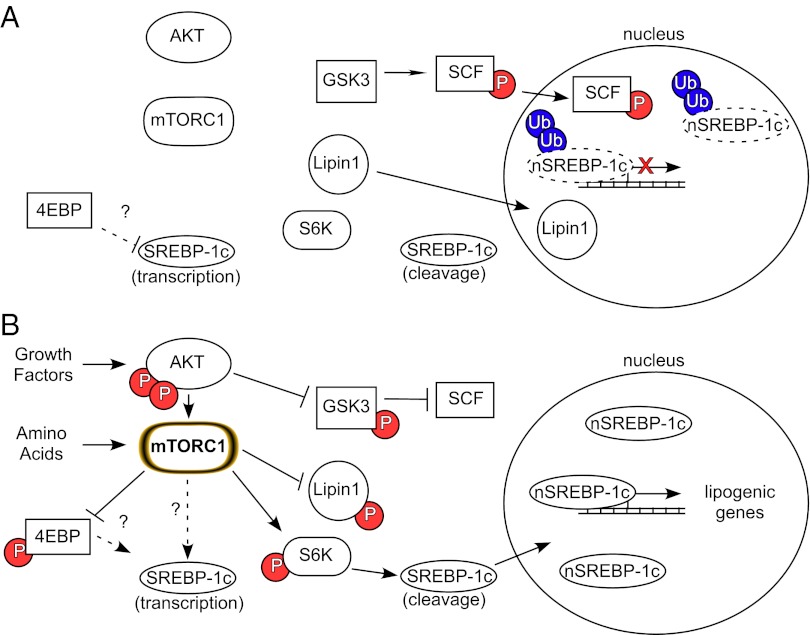

SREBP-1c–dependent stimulation of DNL appears important not only for the pathological state resulting from overnutrition but for maintenance of the unusual metabolic state of many cancers. It has been known for some time that the multiprotein complex mTORC1 resides downstream of PI3K-Akt and functions to integrate signals from growth and survival factors as well as amino acids to promote cellular growth (8). When mTORC1 recognizes the right signal from either a growth factor receptor or oncogene in combination with adequate substrates, it activates a protein translational program that drives cell growth. More recently, mTORC1 has emerged as a central control point for more global anabolic metabolism, including the stimulation of lipogenesis. Recent parallel studies in cancer cells (9) and normal (10) insulin-responsive organs, such as the liver (5), have demonstrated that mTORC1 is required for the increase in SREBP-1 expression and stimulation of its target genes (Fig. 1); whether activation of mTORC1 is sufficient to promote lipogenesis via SREBP-1c is still unclear. Recently, lipin 1, a phosphatidic acid phosphatase, has been advanced as a link between mTORC1 an SREBP-1c action by controlling the concentration of nuclear SREBP-1c (11).

Fig. 1.

Control of SREBP-1c transcription, cleavage, and stability via the AKT-mTORC1 signaling pathway. (A) During fasting or in the absence of growth factors, SREBP-1c transcription and cleavage are depressed and nuclear SREBP-1c (nSREBP-1c) is destabilized and degraded. (B) SREBP-1c abundance, stability, and processing are increased on stimulation of the AKT-mTORC1 signaling pathway, leading to an increase in the transcription of lipogenic genes. 4EBP, 4E binding protein 1; P, phosphorylated; SCF, Skp, cullin, F-box containing complex; Ub, ubiquitin.

In contrast to gene expression, illuminating the role of mTORC1 and its downstream targets in the control of SREBP-1c processing has been much more challenging; in some studies, it has not even been clear that processing is regulated independent of gene expression. Study of the pathways controlling SREBP-1c processing has always been confounded by concomitant changes in SREBP-1c precursor protein levels that inevitably occur following engagement of insulin signaling (12). It is virtually impossible to quantify the rate of generation of the nuclear form when the amount of precursor is also changing. In addition, phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) (13) or cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (CDK8) (14) of a classic phosphodegron motif in SREBP-1c induces its degradation, further complicating the interpretation of experiments on SREBP-1 processing. Owen et al. (3) now overcome these technical limitations by generating a transgene for human SREBP-1c, such that the protein is expressed exclusively in the liver, driven by a promoter that maintains the precursor at constant levels independent of changes in nutritional state or pharmacological manipulation of upstream signaling pathways. The additional clever twist that Owen et al. (3) provide is producing the transgene in rats rather than the much more conventional rodent model, mice. This choice of animal was inspired by the generally recognized but poorly understood (and even more sparsely published) observation that isolated mouse hepatocytes are relatively insensitive to the actions of insulin, particularly in regard to regulation of SREBP-1c. Using this genetically modified rat, Owen et al. (3) show clearly that insulin does indeed increase the levels of the nuclear transcriptionally active form of SREBP-1c and that this is likely due to enhanced proteolytic cleavage rather than protein stabilization. Moreover, they go on to demonstrate that, like the regulation of SREBP-1c gene expression, the mTORC1 complex is absolutely necessary for hormone-dependent activation of SREBP1c processing. Further, using pharmacological reagents, Owen et al. (3) ask which of the many signaling pathways downstream of mTORC1 conveys this message. Inhibition of p70 ribosomal S6 protein kinase (S6K) blocked the insulin-dependent increase in the nuclear form of SREBP-1c (3) but not increased expression of the endogenous gene (12). These data reveal a bifurcation in the regulation of SREBP-1c, distal to mTORC1, such that one arm controls SREBP-1c processing and the other regulates gene expression. Still to be uncovered are the mechanisms by which S6K leads to SREBP-1c cleavage. In reality, S6K has always been a bit of a mystery in regard to its physiological roles, because many of its known substrates do not appear to play a role in the regulation of its canonical target function, protein translation. Perhaps these results from Owen et al. (3) point to an unrecognized function for S6K in the control of membrane protein trafficking or in the retention of ER proteins.

What implications can be drawn from the discovery of a distinct signaling pathway in the control of SREBP-1c expression and trafficking? For one, it raises the possibility that other mTORC1-regulated factors might be important for lipid synthesis. One perplexing mTORC1 target is hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, which has been best characterized in the context of its role as a master transcriptional regulator of the response to reduced oxygen (15). However, HIF-1α is also frequently activated in an mTORC1 manner in cancer, presumably as part of the metabolic adaptions that allow continuous growth in unfavorable conditions. HIF directly stimulates the transcription of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (16, 17), which phosphorylates and inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), favoring glycolysis and lactate production over the citric acid cycle and the generation of lipogenic precursors. Because the synthesis of fatty acids from glucose depends on flux through PDH, it is difficult to understand why a coordinated lipogenic signal by mTORC1 would include inhibition of this enzyme, which is typically stimulated by insulin. It is possible to generate fatty acids from glutamate by reductive carboxylation in the liver, adipose tissue, and some tumors by a pathway not requiring PDH (18–20), but the quantitative contribution of this pathway to normal and pathological lipid accumulation has not been defined. Interestingly, mouse livers, which have constitutive accumulation of HIF-2 by virtue of tissue-specific deletion of von Hippel–Lindau protein, develop steatosis, consistent with HIF-2 being a positive regulator of triglyceride accumulation (21).

The other interesting implication of branched signaling cascades is the possibilities for the development of drugs that target only a subset of the biological effects of insulin. As noted above, this approach has become very appealing since the realization that not all insulin-signaling pathways are affected during the insulin-resistant state. The work of Owen et al. (3) will inevitably lead to strategies to block different components of the activation of lipogenic gene expression in a selective manner, perhaps alleviating the dyslipidemia of T2DM with a minimum of unwanted adverse effects.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 16184.

References

- 1.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Selective versus total insulin resistance: A pathogenic paradox. Cell Metab. 2008;7:95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leavens KF, Easton RM, Shulman GI, Previs SF, Birnbaum MJ. Akt2 is required for hepatic lipid accumulation in models of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;10:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen JL, et al. Insulin stimulation of SREBP-1c processing in transgenic rat hepatocytes requires p70 S6-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16184–16189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213343109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benhamed F, et al. The lipogenic transcription factor ChREBP dissociates hepatic steatosis from insulin resistance in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2176–2194. doi: 10.1172/JCI41636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porstmann T, et al. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell Metab. 2008;8:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang T, et al. Crucial step in cholesterol homeostasis: sterols promote binding of SCAP to INSIG-1, a membrane protein that facilitates retention of SREBPs in the ER. Cell. 2002;110:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon TI, Osborne TF. SREBPs: Metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(2):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yecies JL, et al. Akt stimulates hepatic SREBP1c and lipogenesis through parallel mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways. Cell Metab. 2011;14:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan M, et al. Postprandial hepatic lipid metabolism requires signaling through Akt2 independent of the transcription factors FoxA2, FoxO1, and SREBP1c. Cell Metab. 2011;14:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson TR, et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell. 2011;146:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Bifurcation of insulin signaling pathway in rat liver: mTORC1 required for stimulation of lipogenesis, but not inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3441–3446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundqvist A, et al. Control of lipid metabolism by phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the SREBP family of transcription factors by SCF(Fbw7) Cell Metab. 2005;1:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X, et al. Regulation of lipogenesis by cyclin-dependent kinase 8-mediated control of SREBP-1. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2417–2427. doi: 10.1172/JCI61462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: A metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D Adamo AF, Jr, Haft DE. An alternate pathway of alpha-ketoglutarate catabolism in the isolated, perfused rat liver. I. Studies with dl-glutamate-2- and -5-14C. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:613–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo H, Antoniewicz MR, Stephanopoulos G, Kelleher JK. Quantifying reductive carboxylation flux of glutamine to lipid in a brown adipocyte cell line. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20621–20627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706494200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullen AR, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature. 2012;481:385–388. doi: 10.1038/nature10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rankin EB, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4527–4538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]