Abstract

UV-B light initiates photomorphogenic responses in plants. Arabidopsis UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 (UVR8) specifically mediates these responses by functioning as a UV-B photoreceptor. UV-B exposure converts UVR8 from a dimer to a monomer, stimulates the rapid accumulation of UVR8 in the nucleus, where it binds to chromatin, and induces interaction of UVR8 with CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1), which functions with UVR8 to control photomorphogenic UV-B responses. Although the crystal structure of UVR8 reveals the basis of photoreception, it does not show how UVR8 initiates signaling through interaction with COP1. Here we report that a region of 27 amino acids from the C terminus of UVR8 (C27) mediates the interaction with COP1. The C27 region is necessary for UVR8 function in the regulation of gene expression and hypocotyl growth suppression in Arabidopsis. However, UVR8 lacking C27 still undergoes UV-B–induced monomerization in both yeast and plant protein extracts, accumulates in the nucleus in response to UV-B, and interacts with chromatin at the UVR8-regulated ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5) gene. The UV-B–dependent interaction of UVR8 and COP1 is reproduced in yeast cells and we show that C27 is both necessary and sufficient for the interaction of UVR8 with the WD40 domain of COP1. Furthermore, we show that C27 interacts in yeast with the REPRESSOR OF UV-B PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS proteins, RUP1 and RUP2, which are negative regulators of UVR8 function. Hence the C27 region has a key role in UVR8 function.

UV-B wavelengths (280–315 nm) are a minor component of sunlight but have a major impact on living organisms. The damaging effects of UV-B are well documented, but plants rarely show signs of UV-damage despite constant exposure to sunlight. This is because plants have evolved effective means of protection against UV-B, including the deposition of UV-absorbing phenolic compounds in the outer tissues and the production of efficient antioxidant and DNA repair systems (1–4). These UV-protective mechanisms are stimulated by low doses of UV-B through differential gene expression. Moreover, low levels of UV-B regulate other responses in plants, including the suppression of hypocotyl extension (5). Thus, in plants, UV-B acts as a key regulatory signal that initiates photomorphogenic responses and promotes survival.

The low dose, photomorphogenic responses to UV-B are mediated by the photoreceptor UVR8 (3–7). UVR8 acts specifically in UV-B to regulate over 100 genes, many of which are involved in UV protection (5, 6). Arabidopsis uvr8 mutant plants are highly sensitive to UV-B because they fail to express UV-protective genes (6, 8). Among the genes regulated by UVR8 is that encoding the ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) transcription factor, which mediates most, if not all, gene expression responses initiated by UVR8 (6, 7). UVR8 interacts with chromatin via histones, in particular H2B (9) at the HY5 gene (6, 9) and a number of other UVR8-regulated genes (9), which raises the possibility that UVR8 promotes recruitment or activation of transcription factors and/or chromatin remodeling proteins that regulate target genes such as HY5.

UVR8 is a seven-bladed β-propeller protein (8, 10, 11). UVR8 exists as a homodimer in plants and in vitro, which rapidly dissociates to form monomers following exposure to low doses of UV-B (10–12). Recent elucidation of the crystal structure of UVR8 shows that the dimer is maintained by salt-bridge interactions between specific charged amino acids at the dimer interface (10, 11). UV-B is perceived by specific excitonically coupled tryptophans that are adjacent to salt-bridging arginine residues, and hence photoreception results in breakage of salt bridges leading to monomerization. Photoreception leads to the rapid nuclear accumulation of UVR8 (13) and interaction with the COP1 protein (5, 12). Although necessary for UVR8 function, nuclear localization alone is insufficient to cause expression of target genes; UV-B exposure is still needed to activate UVR8 in the nucleus (13). COP1 and UVR8 regulate essentially the same set of genes (5, 14) and this positive regulatory function contrasts with the role of COP1 as a negative regulator of photomorphogenesis in dark-grown seedlings (15). In UV-B responses, COP1 is required for the stimulation of HY5 gene expression (14), whereas in dark-grown seedlings COP1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase to promote the destruction of HY5 (16). There is no evidence that COP1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase in UV-B photomorphogenic responses, although in principle it could act to degrade an unidentified negative regulator of the responses. The RUP1 and RUP2 proteins negatively regulate UV-B photomorphogenic responses and interact directly with UVR8, but COP1 is required for their UV-B–induced expression, along with UVR8, rather than their degradation (17).

The recent determination of UVR8 structure combined with mutational analysis explains how UVR8 acts in photoreception (10, 11). However, these studies do not show how UVR8 interacts with COP1 to initiate signaling, which is key to understanding UVR8 function. Here we identify the region of UVR8 that interacts with COP1 and show that it has a crucial role in UVR8 function in vivo.

Results

C-Terminal 27-Amino-Acid Region of UVR8 Is Required for Function in Plants.

In a previous mutant screen (6) we isolated several uvr8 alleles (Fig. S1A). One allele (uvr8-2) has a premature stop codon and lacks 40 amino acids at the C terminus of the protein. The truncated protein is detectable in uvr8-2 plants (Fig. S1B) but the mutant fails to induce UVR8-regulated CHS transcripts in response to UV-B exposure (Fig. S1C). A 27-amino-acid region from the C terminus of UVR8 (C27; amino acids 397–423) contains a number of amino acids that are highly conserved among UVR8 proteins from different plant species (boxed in Fig. S2), but not present in sequences related to UVR8, such as eukaryotic RCC1 (8). The fact that these amino acids are lacking in the uvr8-2 mutant led us to investigate their role in UVR8 function.

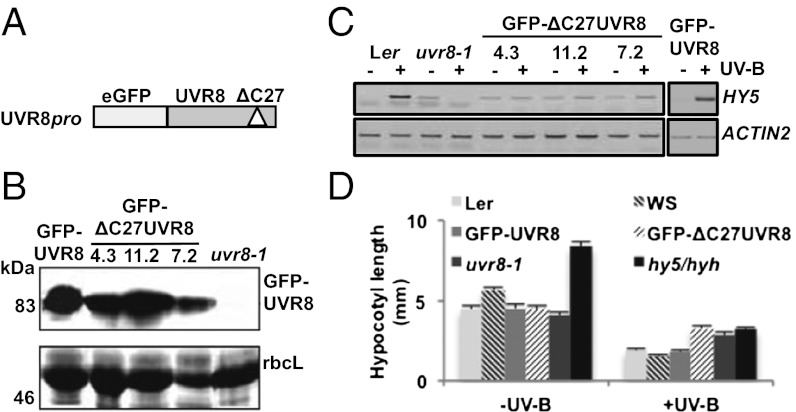

UVR8 lacking specifically the C27 region, with a translational GFP fusion at the N terminus was expressed in uvr8-1 null mutant plants under the control of the native UVR8 promoter (Fig. 1A). The level of expression of the GFP–ΔC27UVR8 fusion in transgenic plants (Fig. 1B) was similar to that of a wild-type GFP–UVR8 fusion that was shown previously to complement the impaired UV-B induction of gene expression in uvr8-1 (13) (Fig. 1C). However, as shown in Fig. 1C, GFP–ΔC27UVR8 fails to complement uvr8-1 in that no UV-B induction of UVR8-regulated HY5 transcripts is observed in three independent transgenic lines. Moreover, uvr8-1 plants transformed with GFP–ΔC27UVR8 are highly sensitive to UV-B, similar to the uvr8-1 mutant (Fig. S3). Therefore, the C27 region is required for UVR8 function in vivo.

Fig. 1.

The GFP–ΔC27UVR8 fusion does not functionally complement transgenic uvr8-1 plants. (A) The GFP–ΔC27UVR8 fusion protein lacking UVR8 amino acids 397–423 coupled to the UVR8 promoter. (B) Western blot of whole cell extracts from uvr8-1 plants expressing UVR8pro:GFP–UVR8 or UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (lines 4.3, 11.2, and 7.2) probed with anti-GFP antibody. Ponceau staining of Rubisco large subunit (rbcL) is shown as a loading control. (C) RT-PCR assays of HY5 and control ACTIN2 transcripts in Ler, uvr8-1, uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (lines 4.3, 11.2, and 7.2) and uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–UVR8 (line 6.2) (13) plants grown under 20 μmol m−2 s−1 white light (−) and exposed to 3 μmol m−2 s−1 broadband UV-B for 4 h (+). (D) Hypocotyl lengths (±SE, n = 10) for 4-d-old wild-type Ler, wild-type Ws, uvr8-1, uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–UVR8, uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (line 4.3), and hy5-ks50 hyh (Ws background) plants grown in 1.5 μmol m−2 s−1 white light (−UV-B) supplemented with 1.5 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B (+UV-B).

To further examine the role of the C27 region in UVR8 function we measured the suppression of hypocotyl extension in response to UV-B, which is mediated by UVR8 (5). Whereas uvr8-1 plants expressing GFP–UVR8 exhibit hypocotyl suppression in UV-B, similar to wild-type, those expressing GFP–ΔC27UVR8 have similar hypocotyl length to uvr8-1 (Fig. 1D), demonstrating that the C27 region is required for UVR8 to mediate the response. Hypocotyl growth suppression by UV-B additionally requires HY5/HYH (Fig. 1D), so the lack of response in uvr8-1 plants and in uvr8-1 expressing GFP–ΔC27UVR8 may result from impaired HY5/HYH gene expression (Fig. 1C) (7).

C27 Region of UVR8 Is Not Required for Interaction with Chromatin, UV-B–Dependent Monomerization, or Nuclear Accumulation.

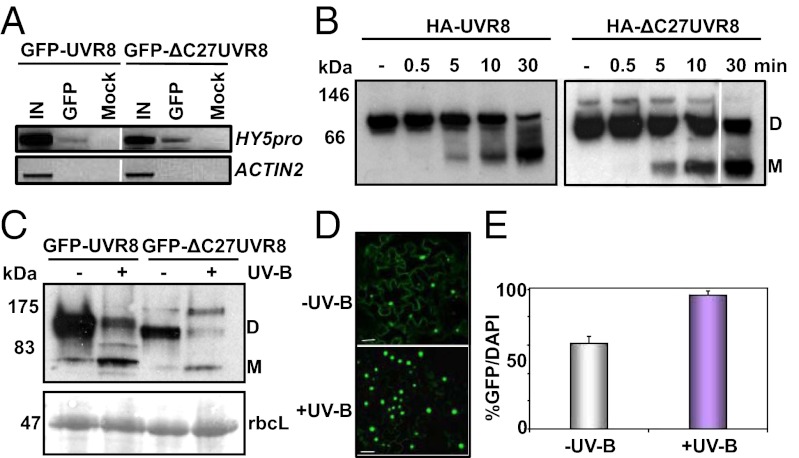

GFP–UVR8 (and native UVR8) binds to chromatin at several genes it regulates, including the HY5 gene (9). Chromatin immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody demonstrates that both GFP–ΔC27UVR8 and GFP–UVR8 associate with chromatin containing the HY5 promoter region but not the control ACTIN2 gene (Fig. 2A). Therefore, although the C27 region of UVR8 is required for function, it is not required for UVR8 to bind to chromatin at a target gene locus.

Fig. 2.

The C27 region of UVR8 is not required for chromatin association, UV-B–induced monomerization or nuclear accumulation. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays of DNA associated with GFP–UVR8 or GFP–ΔC27UVR8. PCR of the HY5 promoter (−331 to +23) and control ACTIN2 DNA from uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–UVR8 and uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (line 11.2) plants grown under 20 μmol m−2 s−1 white light and exposed to 3 μmol m−2 s−1 broadband UV-B for 4 h. IN, input DNA before immunoprecipitation; GFP, DNA immunoprecipitated by anti-GFP antibody; mock, no antibody control. (B) Western blots of whole cell extracts from yeast expressing HA-UVR8 (Left) or HA-ΔC27UVR8 (Right) probed with anti-HA antibody. The yeast extracts were treated (+) or not (−) with 1 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B for the times shown. Samples were run on an 8% native gel. The UVR8 dimer (D) and monomer (M) are indicated. (C) Western blot of whole cell extracts from uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–UVR8 and uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (line 11.2) plants probed with anti-GFP antibody. Extracts were treated (+) or not (−) with 4 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B for 30 min before SDS-loading buffer was added. Samples were then run on a 7.5% SDS/PAGE gel without boiling. Ponceau staining of Rubisco large subunit (rbcL) is shown as a loading control. The UVR8 dimer (D) and monomer (M) are indicated. (D) Confocal images of GFP fluorescence in leaf epidermal tissue of uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (line 11.2) plants grown under 20 μmol m−2 s−1 white light (−UV-B) and exposed to 3 μmol m−2 s−1 broadband UV-B for 4 h (+UV-B). (Scale bars, 20 μm.) (E) Percentage of nuclei identified by DAPI fluorescence in uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (line 11.2) plants showing colocalization of GFP fluorescence under 20 μmol m−2 s−1 white light (−UV-B) and following exposure to 3 μmol m−2 s−1 broadband UV-B for 4 h (+UV-B). Data are the mean ± SE (n = 20 images).

UV-B promotes the conversion of UVR8 from a dimer to a monomer in vitro (10), in plants and when it is expressed heterologously in yeast (12). Fig. 2B shows the effect of UV-B illumination on HA-tagged UVR8 in protein extracts of yeast. Following UV-B illumination of the extracts, proteins were resolved by native gel electrophoresis and HA–UVR8 was detected by an anti-HA antibody. The HA–UVR8 dimer is present before illumination and the monomer is detectable after 5 min illumination with a relatively low fluence rate of UV-B. Longer exposures generate increasing amounts of the monomer while the amount of dimer decreases. The same result is observed with yeast expressing HA–ΔC27UVR8.

UVR8 monomerization is observed when plant extracts are exposed specifically to UV-B wavelengths (Fig. S4) and analyzed by SDS/PAGE without boiling to denature the samples (12). The UVR8 dimer is very resistant to SDS when not boiled (10–12) and only dissociates in the absence of UV-B under low pH (10) or high salt (11). As shown in Fig. 2C, before UV-B illumination of extracts, GFP–UVR8 and GFP–ΔC27UVR8 were present predominantly as the dimer, whereas following UV-B exposure the monomer increased in abundance. These experiments show that the C27 region of UVR8 is not required for the primary effect of UV-B exposure on the protein in vivo, namely conversion from a dimer to a monomer.

Although GFP–ΔC27UVR8 is not functional, it nevertheless still accumulates in the nucleus in response to UV-B illumination of plants. In previous experiments, we showed that GFP–UVR8 is detectable in about half of the nuclei of plants not exposed to UV-B but that UV-B stimulates a rapid increase in both the fraction of nuclei showing GFP fluorescence and the brightness of the fluorescence (13). A very similar response is shown in Fig. 2D for GFP–ΔC27UVR8. Quantification of GFP fluorescence in nuclei identified by DAPI staining shows that UV-B exposure increases the fraction of nuclei containing GFP–ΔC27UVR8 from ∼60% to over 90% (Fig. 2E).

C27 Region of UVR8 Is Required for Interaction with COP1 in Plants and Yeast.

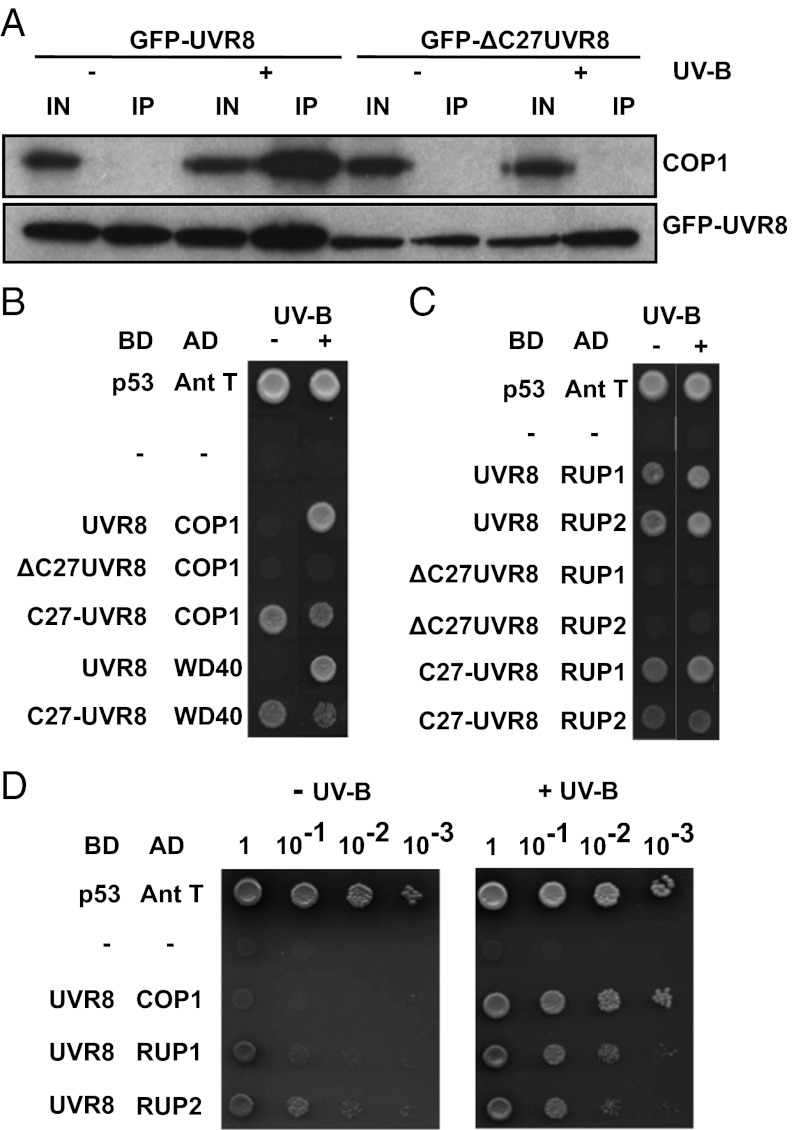

UVR8 interacts with COP1 in a UV-B–dependent manner in plants (5). Here the interaction was tested by immunoprecipitation of GFP–UVR8 and analysis of the immunoprecipitate for the presence of COP1 using an anti-COP1 antibody. As shown in Fig. 3A, for plants expressing GFP–UVR8, COP1 is not detectable in the immunoprecipitate obtained from dark-treated plants but is present following UV-B exposure, indicating interaction with GFP–UVR8. In contrast, COP1 was not detectable in immunoprecipitates of GFP–ΔC27UVR8 from either dark-treated or UV-B–exposed plants. Therefore, the C27 region of UVR8 is required for interaction with COP1 in plants.

Fig. 3.

The C27 region of UVR8 is necessary and sufficient for interaction with both the WD40 region of COP1 and RUP proteins. (A) The ΔC27UVR8 protein does not interact with COP1 in plants. Whole cell extracts were obtained from uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–UVR8 and uvr8-1/UVR8pro:GFP–ΔC27UVR8 (line 4.3) plants treated (+) or not (−) with 3 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B. Coimmunoprecipitation assays were carried out under the same illumination conditions. Input samples (15 μg, IN) and eluates (IP) were fractionated by SDS/PAGE and Western blots were probed with anti-COP1 and anti-GFP antibodies. (B) Yeast two-hybrid plasmids containing a DNA binding domain (BD) and an activation domain (AD) fused to the proteins indicated were cotransformed in yeast, which were then spotted on fully selective media plates. All colonies grew on nonselective media (not shown). As controls, yeast were cotransformed with plasmids containing mammalian p53 and antigen T (positive control) or no inserts (−, negative control). ΔC27UVR8 lacks amino acids 397–423 of UVR8 (Fig. 1A). Construct C27–UVR8 contains only these 27 amino acids of UVR8. WD40 corresponds to the 341 C-terminal amino acids of COP1 (334–675). Yeast were left to grow in darkness (−) or under 0.1 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B (+). (C) Yeast two-hybrid assay undertaken as in B with RUP1 and RUP2. (D) Yeast two-hybrid assay undertaken as in B except that yeast were spotted onto plates in a serial dilution.

To facilitate further study of the interaction between UVR8 and COP1, experiments were undertaken in yeast. The interaction in yeast is specific to UV-B wavelengths and is not mediated by the yeast DNA damage signaling pathway (Fig. S5). As shown in Fig. 3B, deletion of the C27 region prevents interaction of UVR8 with COP1, consistent with the results obtained in plants. The lack of interaction cannot be explained by a failure of the yeast cells to express the proteins, as each protein was detectable (Fig. S6A). The C27 region alone interacts with intact COP1 but the UV-B dependence is lost; interaction is seen in both darkness and UV-B. Intact UVR8 interacts with the WD40 region of COP1 (the C-terminal 341 amino acids) in a UV-B–dependent manner. The C27 region interacts with the WD40 region of COP1, but again not in a UV-B–dependent manner. These results show that a UV-B–dependent interaction requires intact UVR8, whereas intact COP1 is not sufficient, consistent with UVR8 acting as the UV-B photoreceptor for the response. We further conclude that the C27 region of UVR8 is both necessary and sufficient for interaction with COP1 via its WD40 domain.

C27 Region of UVR8 Mediates Interaction with RUP1 and RUP2.

RUP1 and RUP2 negatively regulate UVR8 function in plants and interact directly with UVR8 in the presence and absence of UV-B (17). Because RUP1 and RUP2 are small WD40 proteins and C27 interacts with the WD40 domain of COP1, we tested whether C27 interacts with RUP1 and RUP2. As shown in Fig. 3C, UVR8 interacts with RUP1 and RUP2 in the presence or absence of UV-B in yeast, although examination of a dilution series indicates that the interaction is stronger in the presence of UV-B (Fig. 3D). Moreover, taking into account the similar levels of expression of COP1, RUP1, and RUP2 in the yeast cells (Fig. S6B), the interaction between UVR8 and COP1 in UV-B appears to be at least as strong as between UVR8 and the RUP proteins (Fig. 3D). However, UVR8 lacking C27 fails to interact with either RUP1 or RUP2 (Fig. 3C), although the proteins were expressed in the cells (Fig. S6A). C27 alone interacts with both RUP1 and RUP2. Therefore, C27 is both necessary and sufficient to mediate an interaction between UVR8 and the RUP proteins that is independent of UV-B.

Discussion

Although recent research has established the physiological importance of UVR8 and the structural basis of its action as a photoreceptor, the mechanism of UVR8 signaling, which is initiated by interaction with COP1, is poorly understood. The data presented here show that the C27 region of UVR8 is key to understanding UVR8 signaling. The C27 region is not present in structurally related proteins such as RCC1 and is not present in other Arabidopsis proteins, including those with moderate sequence similarity to UVR8. However, the C27 region contains stretches of amino acids that are highly conserved in UVR8 sequences from various plant species, including lower plants, consistent with its importance in UVR8 function. Both the uvr8-2 allele, which lacks the C-terminal 40 amino acids of the protein, and transgenic uvr8-1 plants expressing the GFP–ΔC27UVR8 fusion show no detectable UV-B induction of HY5 or CHS transcripts. It is known that HY5, sometimes acting redundantly with the closely related HYH (HY5 HOMOLOG) transcription factor (7, 18), has a key role in mediating UVR8-regulated gene expression (5, 6), and hence the loss of HY5 expression in plants lacking C27 will impair responses. Thus, uvr8-1 plants expressing GFP–ΔC27UVR8 are both highly sensitive to UV-B, likely because of a general absence of UVR8-regulated gene expression, and impaired in the suppression of hypocotyl growth by UV-B, similar to uvr8-1 (5, 6, 8) and hy5 (6) or hy5 hyh (7) mutants.

The loss of function of GFP–ΔC27UVR8 is not because deletion of the C-terminal region of UVR8 leads to instability and degradation of the protein, as the mutant protein is expressed in both uvr8-2 and transgenic GFP–ΔC27UVR8 plants. The nonfunctional GFP–ΔC27UVR8 protein still forms a dimer, as in the wild-type, indicating that the C27 region is not required for interaction between UVR8 molecules. Moreover, the GFP–ΔC27UVR8 protein is converted to a monomer following UV-B exposure in both yeast and plants, and so the primary effect of UV-B on the protein is not prevented by the C27 deletion. Similar findings are obtained with purified trypsin-treated UVR8 lacking 40 amino acids at the C terminus (10). Furthermore, the GFP–ΔC27UVR8 protein accumulates in the nucleus of plants in response to UV-B and interacts with chromatin at the HY5 gene similar to wild-type UVR8. Thus, the C27 region is not required for nuclear accumulation of UVR8 and its interaction with histones.

The data presented here show that the C27 region is required for the interaction of UVR8 with COP1, which is pivotal to photomorphogenic UV-B responses. The ΔC27UVR8 protein fails to interact with COP1 in either yeast or plants. Although COP1 is required for the induction of gene expression by UVR8, it is not required for either monomerization (12) or the interaction of UVR8 with chromatin (5), consistent with the findings reported here for plants expressing GFP–ΔC27UVR8. The observation that the GFP–ΔC27UVR8 protein accumulates in the nucleus in response to UV-B indicates that this process also does not require COP1. The experiments in yeast show that the C27 region is both necessary and sufficient for interaction with the WD40 region of COP1. Holm et al. (18) identified a motif in HY5 and several other proteins that is responsible for interaction with the WD40 region of COP1. This motif (VPE/D-hydrophobic residue-G with several upstream negatively charged residues) is partly conserved in the C27 region of UVR8 (VPDETG with one upstream glutamate residue) and could be involved in the interaction with COP1.

There is no reason to suppose that yeast itself contains a photoreceptor that would mediate the UV-B–dependent interaction between UVR8 and COP1. Yeast is very unlikely to have a protein that could substitute as a plant UV-B photoreceptor and the activation of DNA damage signaling is not responsible for initiating the interaction between UVR8 and COP1. This interaction is induced specifically by UV-B wavelengths and requires intact UVR8 acting as the photoreceptor. Intact UVR8 is able to mediate a UV-B–dependent interaction with the WD40 region of COP1 alone, whereas intact COP1 is unable to mediate a UV-B-dependent interaction with the C27 region alone, and thus C27 binds to COP1 (and specifically to the WD40 domain) in both darkness and following UV-B exposure. It is interesting that the C27 region alone binds constitutively to COP1, whereas intact UVR8 binds to COP1 only following UV-B exposure. It is possible that the C27 region is shielded from COP1 in intact UVR8, which is in the dimeric form in darkness, and that UV-B–induced monomerization, together with associated conformational changes, exposes the C27 region to COP1. The crystal structure of UVR8 (10, 11) does not include the C-terminal 40 amino acids and hence it is important to determine where the C27 region resides in the protein and whether its position changes after UV-B exposure.

COP1 interacts with various other components involved in regulating photomorphogenesis, including the cry1 photoreceptor (19, 20), SPA proteins (21), CULLIN4, and DAMAGED DNA BINDING PROTEIN1 (DDB1) (22, 23). Hence UVR8 could possibly interact with other photomorphogenic proteins via its association with COP1 or influence the interaction of COP1 with other components. For instance, the interaction of COP1 with UVR8 might reduce its availability to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase in association with other proteins (23). Moreover, interaction with UVR8 following UV-B exposure could possibly inhibit the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of COP1 and contribute to the light inactivation of COP1, which is not fully understood (15). Thus, further research is required to establish both how the interaction of UVR8 with COP1 leads to transcriptional regulation in photomorphogenic UV-B responses and how it impacts on the function of COP1 in other photomorphogenic responses.

RUP1 and RUP2 are WD40 repeat proteins, like COP1 (17), and the data presented here indicate that they interact with the C27 region of UVR8, which also binds COP1. Hence, in addition to its key role in binding COP1 to initiate signaling, the C27 region is important in the regulation of UVR8 activity through its ability to interact with other WD40 proteins. Although the interaction of RUP1 and RUP2 with C27 is stimulated by UV-B in yeast, both proteins bind to UVR8 in the absence of UV-B, in contrast to COP1, whose interaction is dependent on UV-B. As discussed above, COP1 is unable to access C27 in the UVR8 dimer. The much smaller size of the RUP proteins does not explain their stronger interaction with the C27 region in darkness, because the WD40 region of COP1 alone, which is similar in size to the RUP proteins, shows a UV-B–dependent interaction with C27 (Fig. 3B). Hence, there are likely differences in the primary sequence or structure of the RUPs compared with the WD40 region of COP1 that enable them to interact with the C27 region in dimeric UVR8. It is not clear how the RUP proteins repress UV-B photomorphogenic responses in vivo. The data presented here suggest that COP1 and the RUP proteins have similar strength of interaction with C27 in yeast in the presence of UV-B, so the RUPs may not impair interaction of COP1 with UVR8 in plants by having greater binding affinities for C27. Because the RUPs are UV-B induced, an increase in their abundance relative to COP1 may limit binding of COP1 to C27. However, more detailed study of the amounts, availability, and binding affinities of the proteins in planta is needed to understand the mechanism of negative regulation.

Methods

Plant Materials, Treatments, and Assays.

Wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Wassilewskija (Ws), the uvr8-1 mutant (Ler background) (8) and hy5-ks50 hyh double mutant (Ws background) (18) were used in these experiments. All transgenic lines were produced in the uvr8-1 mutant. Details of seed origin, production of the GFP–ΔC27UVR8 construct (UVR8 lacking amino acids 397–423), plant transformation, and growth conditions are given in SI Methods. Plants were exposed to either broadband UV-B (spectrum in Fig. S7A) or narrowband UV-B (spectrum in Fig. S7B), as indicated in Fig. S7 legends.

RT-PCR experiments, ChIP assays, and GFP–UVR8 subcellular localization analyses were undertaken as described in refs. 7, 9, and 13, respectively.

UVR8 Dimer/Monomer Analysis.

UVR8 fused to the HA epitope was expressed in yeast and whole cell extracts were prepared as described in SI Methods. Aliquots of the extracts were exposed to 1 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B. Proteins were fractionated on a 8% (wt/vol) native PAGE gel and Western blots probed with anti-HA antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; 2367).

Plants were grown on agar plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 constant white light at 21 °C for 10 d then put in darkness for 16 h. Arabidopsis whole cell extracts were prepared as described (13) and monomerization of UVR8 in the extracts was examined essentially as described (12). Whole cell extracts were kept on ice in the absence or presence of 4 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B for 30 min. Four times loading buffer [250 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 6.8, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 20% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol, 40% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5% bromophenol blue] was added to the samples. The proteins were loaded on a 7.5% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE gel without boiling. Western blots were incubated with anti-GFP antibody as described (13). The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay.

Proteins were cloned as fusions with either the DNA binding domain or activation domain of the yeast transcription factor GAL4 (primers used for generating fusion proteins are listed in Table S1). Vectors containing the fusions were transformed into yeast and interaction between proteins was assayed by growth on fully selective medium for 3 d at 30 °C either in darkness or under 0.1 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B. Controls for autoactivation are shown in Fig. S8. The data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments. Full details are given in SI Methods.

Coimmunoprecipitation of UVR8 and COP1.

Plants were grown on agar plates containing half-strength MS salts under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 constant white light at 21 °C for 12 d then put in darkness for 16 h. The plants were treated for 3 h with 3 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B. Arabidopsis whole cell extracts were prepared as described in ref. 13 in the absence or presence of 3 μmol m−2 s−1 narrowband UV-B. The coimmunoprecipitation assays were carried out in the same conditions. Samples were incubated for 30 min on ice with 50 μL anti-GFP microbeads (μMacs, 130–091-370; Miltenyi Biotec). The microcolumn was equilibrated using 200 μL high-salt lysis buffer [450 mM NaCl, 1% Triton (vol/vol), 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 5 mM PMSF, protease inhibitors, Complete Mini, 11836153001; Roche]. The lysate was applied onto the column and left to run through. After five washes with 200 μL of high-salt lysis buffer and one wash with 300 mM NaCl, Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 20 μL of elution buffer (0.1 M triethylamine pH 11.8, 0.1% Triton X-100) was applied onto the column and left for 5 min at room temperature. An extra 50 μL of elution buffer was added and the eluate was collected in a tube containing 3 μL of 1 M Mes, pH 3 for neutralization. The eluates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE gel and Western blot using antibodies anti-GFP or anti-COP1 (kindly provided by Nam-Hai Chua, The Rockefeller University, New York) (24). Data are representative of at least three experiments.

Full details of all materials and methods are given in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roman Ulm for sharing data on UVR8 monomerization prior to publication and guidance with defining the COP1 WD40 domain, Drs. In-Cheol Jang and Nam-Hai Chua for sending the COP1 antibody, Jane Findlay for technical assistance, and Jane Forrester for preliminary experiments with the RUP proteins. This research was supported by grants from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and The Leverhulme Trust. E.K. was supported by a University of Glasgow doctoral studentship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210898109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Frohnmeyer H, Staiger D. Ultraviolet-B radiation-mediated responses in plants. Balancing damage and protection. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1420–1428. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.030049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulm R, Nagy F. Signalling and gene regulation in response to ultraviolet light. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins GI. Signal transduction in responses to UV-B radiation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:407–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heijde M, Ulm R. UV-B photoreceptor-mediated signalling in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favory JJ, et al. Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2009;28:591–601. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown BA, et al. A UV-B-specific signaling component orchestrates plant UV protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18225–18230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507187102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown BA, Jenkins GI. UV-B signaling pathways with different fluence-rate response profiles are distinguished in mature Arabidopsis leaf tissue by requirement for UVR8, HY5, and HYH. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:576–588. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kliebenstein DJ, Lim JE, Landry LG, Last RL. Arabidopsis UVR8 regulates ultraviolet-B signal transduction and tolerance and contains sequence similarity to human regulator of chromatin condensation 1. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:234–243. doi: 10.1104/pp.005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloix C, Jenkins GI. Interaction of the Arabidopsis UV-B-specific signaling component UVR8 with chromatin. Mol Plant. 2008;1:118–128. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssm012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christie JM, et al. Plant UVR8 photoreceptor senses UV-B by tryptophan-mediated disruption of cross-dimer salt bridges. Science. 2012;335:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1218091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu D, et al. Structural basis of ultraviolet-B perception by UVR8. Nature. 2012;484:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizzini L, et al. Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science. 2011;332:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1200660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiserli E, Jenkins GI. UV-B promotes rapid nuclear translocation of the Arabidopsis UV-B specific signaling component UVR8 and activates its function in the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2662–2673. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oravecz A, et al. CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 is required for the UV-B response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1975–1990. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi C, Deng XW. COP1: From plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW. Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2000;405:462–466. doi: 10.1038/35013076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber H, et al. Negative feedback regulation of UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20132–20137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914532107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holm M, Hardtke CS, Gaudet R, Deng XW. Identification of a structural motif that confers specific interaction with the WD40 repeat domain of Arabidopsis COP1. EMBO J. 2001;20:118–127. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H-Q, Tang R-H, Cashmore AR. The signaling mechanism of Arabidopsis CRY1 involves direct interaction with COP1. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2573–2587. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li QH, Yang HQ. Cryptochrome signaling in plants. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:94–101. doi: 10.1562/2006-02-28-IR-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu D, et al. Biochemical characterization of Arabidopsis complexes containing CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 and SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA proteins in light control of plant development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2307–2323. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen H, et al. Arabidopsis CULLIN4 forms an E3 ubiquitin ligase with RBX1 and the CDD complex in mediating light control of development. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1991–2004. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, et al. Arabidopsis CULLIN4-damaged DNA binding protein 1 interacts with CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1-SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA complexes to regulate photomorphogenesis and flowering time. Plant Cell. 2010;22:108–123. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.065490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jang I-C, Henriques R, Seo HS, Nagatani A, Chua N-H. Arabidopsis PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR proteins promote phytochrome B polyubiquitination by COP1 E3 ligase in the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2370–2383. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.