Abstract

In an era when health resources are increasingly constrained, international organisations are transitioning from directly managing health services to providing technical assistance (TA) to in-country owners of public health programmes. We define TA as: A dynamic, capacity-building process for designing or improving the quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of specific programmes, research, services, products, or systems’. TA can build sustainable capacities, strengthen health systems and support country ownership. However, our assessment of published evaluations found limited evidence for its effectiveness. We summarise socio-behavioural theories relevant to TA, review published evaluations and describe skills required for TA providers. We explore challenges to providing TA including cost effectiveness, knowledge management and sustaining TA systems. Lastly, we outline recommendations for structuring global TA systems. Considering its important role in global health, more rigorous evaluations of TA efforts should be given high priority.

Keywords: technical assistance, research utilisation, programme effectiveness, programme evaluation, research to practice

Introduction

Over the past half-century, international nongovernmental organisations (INGOs) have made many contributions to the health and development needs of low-income countries. They have brokered funding, established programmes, conducted research and helped deliver services on an enormous scale. However, the role of INGOs is changing. In May 2009, President Obama announced the Global Health Initiative (GHI) - a major effort by the US Government (USG) to address public health issues around the world. The GHI encourages INGOs to transition from managing service delivery programmes to providing more technical assistance (TA). Under this transition, country governments and local organisations will own, manage, strengthen and sustain their national health programmes (USAID 2010). Other funders have called for INGOs to make similar changes in their roles (OECD 2010, The Global Fund 2010).

Finding more effective and efficient ways to deliver TA is a priority for achieving global health goals. However, no guidelines or model systems have been generally accepted to define TA or direct TA efforts (Potter and Brough 2004). Some TA activities lack focus, follow through and contextual sensitivity. Also, many TA services are uncoordinated across organisations and vary widely in their quality and comprehensiveness (Mitchell et al. 2002, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2007, Curry et al. 2010, Government Accountability Office and President's Emergency Plan for AIDs Relief 2010, OECD 2010, UNAIDS 2011). Because TA is an important means for capacity-building and a core activity in the emerging field of ‘implementation science’, TA methods need to become more evidence-based, standardised and rigorously evaluated (Potter and Brough 2004, Padian et al. 2011).

To advance our understanding of global health-related TA practices, systems and needs, we review published evaluations and relevant theories. We define TA, describe delivery systems and summarise what is known about TA practices and effectiveness. We also outline the skills required for competent TA providers and present suggestions for increasing cost-effectiveness and sustaining high-quality TA systems. Our findings may also be applicable beyond global health, to organisations working in other domains (e.g., human services, international monetary policy, disaster response and defense) engaged in improving their TA systems (Neufeld 1978, Marincioni 2007, Gibbs et al. 2009, Gates 2010).

Defining TA

We were unable to find a commonly accepted definition of TA in the published literature. To most, TA is a simple, straightforward activity: (1) a programme manager requests help or a technical expert identifies a need to design a new or enhance an existing programme; (2) a content expert is identified to provide the assistance; (3) the TA is provided; and (4) recommendations from the TA are put into practice. But, even a superficial assessment will quickly reveal that providing effective TA is a complex and challenging process.

Structurally, TA is provided through a broad range of systems, using a variety of methods. TA can be a one-time activity performed by consultants or long-term assistance provided by a resident advisor (Mitchell et al. 2002). A TA system can be highly centralised with a core group of providers, or it can be decentralised, with loose coordination of short-term independent consultants (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2007, Tyson and McNeil 2009). TA activities often include training, mentoring, reviewing literature, analysing data, and developing and disseminating tools and guidelines that are tailored to address specific technical needs.

Some have proposed that a TA system should function as an ‘interpretive bridge’ to catalyse improvement (Logan et al. 2005). Clearly, TA should help programme staff learn about relevant developments in science, technology and programme practice. TA can also be a platform for linking research to action to meet the specific needs of an organisation (Mitchell et al. 2002, Kegler and Redmon 2006, Lavis et al. 2006). In practice, TA most often involves responding to requests for short-term assistance. It usually does not include a systematic assessment of need or the development of long-term plans for improving the effectiveness of programmes (Backer et al. 1995, Mitchell et al. 2002, Potter and Brough 2004, Lavis et al. 2006, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2007, Bertozzi et al. 2008, Durlak and DuPre 2008, The Global Fund 2010). To capture the evolving need for TA in a transitioning world, we propose the following comprehensive, system-based definition: ‘TA is a dynamic, capacity-building process for designing or improving the quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of specific programmes, research, services, products, or systems. A TA system continually assesses TA needs and monitors the relevance and utility of an evolving base of experience, knowledge, and technology. It assists others in adapting and applying new knowledge, technology, and innovative practices to improve outcomes and increase impact’.

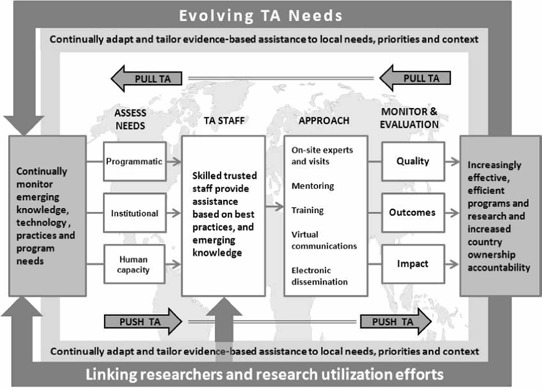

Two major concepts underlay TA (Figure 1): market ‘pull’ and technology ‘push’ (Rimer et al. 2001, Mitchell et al. 2002). Pull begins at the programme level. It facilitates access to technical information that programme implementers believe they need. Thus, pull TA reactively responds to requests for support. Push TA proactively integrates emergent knowledge, research findings and technology into programme practice (Rimer et al. 2001, Lavis et al. 2006). Push TA often begins at the central level and targets groups of programmes, helping them adopt innovations, technologies and new treatment regimens or programme approaches. But the push component can also involve assessing the needs of multiple programmes and promoting the use of up-to-date knowledge, extant research findings and proven interventions.

Figure 1.

A dynamic TA system model.

Logically, as pull and push are mutually reinforcing concepts, TA systems should include both. Programme managers who request assistance (pull TA) can benefit from learning about TA systems and resources, and TA providers trying to integrate new knowledge and technology (push TA) can learn about programme needs, challenges and capabilities. TA providers who respond to pull requests can build trust with programme staff, which facilitates the integration of research findings or evidence-based practices into local programmes. Push initiatives can help programme managers not only improve their efforts but also encourage the use of the TA system when needs emerge.

TA provider knowledge and skills

Successful TA providers must understand the experience, context, capabilities and challenges of the programmes they are trying to support (Blanchard and Aral 2010). Knowledge of changing programme needs and implementation capacities is required to determine evolving TA priorities. Moreover, TA providers must evaluate and synthesize information from multiple sources and agree on the most relevant, feasible solutions to address identified needs and local circumstances. They must also engage the recipients of TA when designing and delivering the assistance (rather than merely disseminating information). Above all, effective TA providers must maintain trusting relationships with the programmes they are serving. Without such trust, recommendations may not be heeded by TA recipients, even when compelling evidence for their effectiveness exists (Mitchell et al. 2002, Rogers 2004).

Because TA can help improve the quality and relevance of research (as well as programmes), TA providers who support in-country research teams (push) need to be familiar and experienced with the scientific, regulatory and operational issues likely to be encountered. For example, in the recently completed CAPRISA 004 clinical trial (which demonstrated that a vaginal gel containing the antiretroviral drug tenofovir can prevent HIV among women), experienced biostatisticians, data managers, social scientists and communications experts provided scientific and operational support to the South African investigators (Abdool Karim et al. 2010).

Relevant theories

Many behavioural change, social and system theories are relevant to understanding issues surrounding TA. Although a full discussion of these theories is beyond the scope of this article, we will highlight three of the most relevant.

Diffusion of Innovation theory, which defines diffusion as the process by which an innovation is disseminated over time among members of a social system, is especially germane to understanding how to structure TA systems and improve their effectiveness (Valente and Rogers 1995, Rogers 2002). For an innovation to be accepted, diffusion theory indicates that the advantage of integrating it into practice must be clear and compatible with the local context. Recommendations by TA providers will probably not be accepted by programmes if the innovation is not based on evidence, cannot be easily implemented or is inconsistent with local needs. Diffusion theory also predicts that early adopters and peer opinion leaders will be the most influential agents of change and that a critical mass of adopters will be needed for system-wide change (Rogers 2002, 2004 Bertrand 2004, Chinman et al. 2005, Peterson et al. 2007).

Social cognitive theory, with its core concept of self-efficacy, also provides insight into TA systems. Based on this theory, we expect that confident, well-prepared TA providers who have strong evidence supporting their recommendations are most likely to succeed. Conversely, some local health officials (even if they are convinced that implementing the recommendations will enhance operations) may doubt they have sufficient skills to implement them or to gain support from higher-ranking local policy-makers (Leviton 1989, Bandura 1999, Pajares 2002). Although training on how to be a good TA provider is rarely mentioned in the literature, social cognitive theory explains that people learn from others who model ‘skilled’ behaviour. Much like proponents of diffusion theory, proponents of social cognitive theory may stress that priority should be given to ‘pushing’ into practice the TA recommendations that have the most compelling evidence of significant benefit.

Finally, readiness-to-change theory builds on the concept that, like individuals, communities and organisations can be at different stages of readiness to receive TA (Edwards et al. 2000, Mitchell et al. 2002). Assessing readiness to receive TA and to integrate new knowledge or technology into practice can help determine which organisations should have priority for receiving TA. Applying this theory can also help identify the most effective TA methods for a given context (Leviton 1989, Prochaska et al. 1993, Valente and Rogers 1995, Edwards et al. 2000).

Evidence for TA effectiveness

To assess the effectiveness of TA, we used the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews (Moher et al. 2009) to examine the scientific literature from January 2000 through October 2010 for published evaluations of TA. We searched both PubMed and POPLINE databases using the keywords ‘technical assistance', ‘research utilisation', ‘research to practice’ or ‘technology transfer’ coupled with ‘assessment', ‘evaluate', ‘evaluation’ or ‘study'. Our initial search found 1181 articles, of which 1067 were excluded as irrelevant or incomplete based on our review of abstracts. We reviewed the full text of the remaining 114 articles (including 16 we had identified through reviewing citations). Of these articles, 23 were included in our assessment (Table 1). Each article met the following inclusion criteria: (1) was an evaluation of TA that had been provided to a specific programme or system, (2) described the methods used to provide the TA and (3) presented data relevant to the TA. While we may have missed some evaluations indexed with different keywords, our review was extensive. We did not systematically assess the quality of the study methods or try to rank the evaluations.

Table 1.

A summary of published evaluations of technical assistance: 2000–2010.

| Lead author | Yeara | Recipients (n) | Locationb | Focus | Study designc | Major Findings and conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly (Kelly et al.) | 2000 | ASOs (83) | Metropolitan areas in 47 US states | HIV prevention | E, RR, CG | Active collaboration between researchers and service agencies results in more successful adoption of evidence-based practices than distribution of implementation packages alone |

| Stevenson (Stevenson et al.) | 2002 | CBOs (13) | RI, US | Substance abuse | CS | A needs assessment was useful in focusing technical assistance. TA and training can build confidence in evaluation methods |

| Jolly (Jolly et al.) | 2003 | CBO (98) | 8 US cities | HIV prevention | QA | Preferred TA providers have practical experience, accessibility, cultural competence and communications skills |

| Kelly (Kelly et al.) | 2004 | ASOs (86) | 78 countries | HIV prevention | E, RR, CG | Advanced communication technologies can provide a cost-effective means to disseminate new intervention models worldwide |

| Mitchell (Mitchell et al.) | 2004 | Community coalitions (41) | ME, US | Behavioural andcommunityhealth | QE, CG | While coalition effectiveness improved, no explicit relationship was found between the amount of TA delivered and coalition effectiveness |

| Batchelor (Batchelor et al.) | 2005 | CPG/Prevention agencies (21) | TX | HIV prevention | QE | Increased use of behavioural data in planning |

| Kegeles (Kegeles and Rebchook) | 2005 | CBOs, ASOs and LHDs (44) | US | HIV prevention | QA | Collaboration between TA providers and CBOs increased evaluation capabilities |

| Tang (Tang et al.) | 2005 | Health promotion practitioners (240) | China(7 cities/oneprovince) | Health promotion | QE, CS | Marked improvements in key reform areas and self reported knowledge |

| Kegler (Kegler and Redmon) | 2006 | CHP (48) | US | Tobacco control | QA | TA services resulted in increased knowledge and skills, strengthened leadership and partnership and changes in program practices |

| Florin (Florin et al.) | 2006 | CBOs (9) | RI, US | Tobacco control | QE | Understanding of the programme logic model facilitated TA services. Continued interaction between TA providers and programme coordinators helped identify needs and target TA |

| Harshbarger (Harshbarger et al.) | 2006 | CBOs and LHDs(162) | US | HIV prevention | QE | Proactive offering of TA is needed for interventions to be successfully adapted and implemented with fidelity to core elements and to ensure programme sustainability |

| Olivia (Oliva et al.) | 2007 | LHDs (61) | US | Maternal and child health | QE | TA strategies are associated with better use of data for community assessments, planning and use of grant funds |

| Peterson (Peterson et al.) | 2007 | CHP (7) | NM, US | Behavioural health | CS | Collaborative efforts and community participation are critical to facilitate utilisation of behavioural health research findings |

| Spoth (Spoth et al.) | 2007 | Community/ University Teams (14) | IO, PA | Drug abuse | E, CG, RR | TA and frequency of TA requests were associated with higher recruitment rates |

| Chinman (Chinman et al.) | 2008 | Community coalitions (10) | CA & SC, US | Substance abuse | E, CG | GTO model can build individual capacity and enhance programme performance |

| Emmons (Emmons et al.) | 2008 | Elementary schools (28) | MA | Skin cancer | E, RR, CG | Schools increased their adoption of sun protection policies |

| Feinberg (Feinberg et al.) | 2008 | Community coalitions (96) | PA, US | Adolescent behavioural | QE, CG | Compared dosage of TA received. Results demonstrate limited impact of TA on board functioning |

| Riggs (Riggs et al.) | 2008 | Community coalition (24) | 5 US States | health Drug abuse | E, CG, RR | Increasing effectiveness of the internal coalition results in an equally effective response on evidence-based prevention programmes |

| Hunter (Hunter et al.) | 2009 | Community coalitions (2) | US | Substance abuse | QE | Effective TA models consist of two-way interactions that emphasize collaboration between TA providers and recipients |

| Mayberry (Mayberry | 2009 | CBOs (24) | 9 US states | HIV prevention | QE | Providing TA markedly enhance CBO capacity to plan, implement and evaluate interventions |

| et al.) Gibbs (Gibbs et al.) | 2009 | CBOs (4) | TX, KS, MO, DC,/US | Sexual violence prevention | QE | TA systems should invest in relationship building, collaborate with program staff, tailor TA to programme preferences, and combine structured with programme-specific TA |

| Kalichman (Kalichman et al.) | 2010 | CBOs (111) and LHDs (11) | 37 US states | HIV prevention | QE, | Interventions are commonly adapted to improve community fit and meet programme constraints. Programmes found adapted interventions to be beneficial |

| Rohrbach (Rohrbach et al.) | 2010 | High schools (65) | US | Drug abuse | E, CG, RR | Comprehensive intervention support (with TA) results in stronger effects on implementation fidelity |

Year of publication.

US state abbreviations used.

E, experimental; QE, quasi-experimental; CG, comparison group; RR, random assignment of respondents; QA, qualitative assessment; CS, case study.

Note: ASO, AIDS service organisation; CBO, community-based organisation; CHP, community health programmes; CPG, community planning groups; GTO, Getting to Outcomes project; LHD, local health department.

The TA field is characterised by many unpublished reports in the ‘grey’ literature that are not peer reviewed and can be hard to access. We assessed reports appearing in the grey literature during 2010–2011 using the same keywords and criteria used to search the scientific literature by combing the USAID Development Experience System (DEXS), Google and Google scholar. We reviewed 520 reports and found many descriptive programme evaluations in multiple countries, but no specific evaluations of TA that met our criteria.

Only 2 of the 23 published evaluations had an international focus. The remaining 21 evaluated TA provided to US-based organisations. All 23 described their TA approach and methods in detail, and nine included a comparison or control group and six randomised respondents. All of the evaluations documented some benefit of TA on programme operations, programme outcomes or organisational capacities. Four of the articles assessed the degree to which NGOs receiving TA maintained ‘fidelity’ in adapting interventions into their programmes. Encouragingly, the evaluations that used the most rigorous methods tended to produce the most compelling findings. Although limited, the published evidence suggests that easily accessible, collaborative TA systems that include continued interaction between providers and recipients are most likely to have an impact.

Results of the two internationally focused TA evaluations largely echoed what has been learned from US domestic evaluations. They used two different, but both apparently effective, methods of providing TA. The first evaluation targeted 86 AIDS NGOs in 78 countries using a new intervention. The NGOs were randomised either to receive enhanced TA support or to be in a control group. The NGOs that received enhanced TA support participated in an interactive distance-learning curriculum coupled with telephone consultations with a behavioural scientist. The NGOs in the control group received reference materials with no consultations. The investigators found that virtual systems can effectively link service providers to support for adopting a science-based programme. Twenty-seven (64%) of the 42 NGOs receiving enhanced TA support, versus only 14 (34%) of the 41 control NGOs, developed a new or modified an existing programme (Kelly et al. 2004).

The second evaluation was of TA services provided to health-promotion practitioners during a major TA project to build capacity for community-based health in China. Rather than using a series of ad hoc consultancies, the project used a progressive approach to introduce new concepts (for promoting community health) that called for an increasing degree of Chinese input and management to ensure sustainability and maintenance of technical support. The evaluation utilised a range of quantitative and qualitative methods, including pre/post surveys of practitioners; independent assessments commissioned by the World Bank; content reviews of plans, proposals and evaluation reports; and a post-project review of newly developed policies, strategies and guidelines. However, it did not include a comparison group. The results showed many practical changes in knowledge and skills, which were reflected in annual plans, project proposals, implementation and evaluation reports, and guidelines for schools, hospitals, workplaces and communities. The TA providers also achieved a trustworthy, respectful working relationship with Chinese colleagues that contributed to its success (Tang et al. 2005).

Although relevant theory and published evidence on the effectiveness of TA provide a reasonable foundation for structuring and implementing TA systems, there are many unanswered questions and little data on providing TA in developing countries or in different cultural contexts. As TA is a major activity of the GHI and other global programmes, we believe that the emerging framework for implementation science, proposed for programmes supported by the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), urgently needs to be applied to TA. This framework includes more rigorous monitoring and evaluation, operations research and evaluation of impact to improve quality and effectiveness (Padian et al. 2011).

Challenges to TA systems

Challenges to TA systems are common. For example, inadequate funding and non-availability of qualified TA providers may limit responses to pull requests. Once on site, challenges in defining expectations, agreeing on priorities, establishing collaboration with programme staff and providing TA with sufficient ‘dose’ strength can arise. Accepting too many TA requests can reduce the quality of assistance (Mitchell et al. 2002, Hunter et al. 2009). Lastly, some organisations are not ready to receive TA, believe it is too costly, or do not have the capacity to implement recommendations (Rogers 2002, Greenhalgh et al. 2004, Logan et al. 2005). With all of these challenges, it is not surprising that TA systems also have difficulty retaining their experienced staff. INGOs have encountered all of these issues, finding them to be amplified by the geographic scope and multicultural requirements of global efforts.

Knowledge management

All TA systems need to manage an increasing amount of scientific or technical knowledge to determine what is most useful for local programmes. Thousands of publications and reports of innovative global health practices are generated each year. For example, during 2010, more than 14,000 publications on HIV/AIDS issues, nearly 3000 on malaria, and more than 5300 on tuberculosis alone were cited in PubMed. Screening systems can help TA providers identify the most relevant publications to share with TA recipients, but programme managers are often unable to review the vast amount of information to identify what could help improve their services (Goldstein et al. 1998, Bertozzi et al. 2008).

Internet sites and other sources of programmatic information also exist, but most focus on US domestic issues (Goldstein et al. 1998, Armstrong and Del Rio 2009). Moreover, reports of evaluations of international programmes are difficult to access. Even when available, programme managers may not know which sources of information are authoritative, reliable and up to date (USAID 2011). TA systems need to have user-friendly procedures for assessing proposed best practices (from all sources) for the quality, relevance and feasibility of implementation (Rimer et al. 2001, Bertozzi et al. 2008).

Supporting research to practice

Once a study is completed, translating findings into use can also be frustratingly difficult (Rogers 2002). A survey of researchers in 10 countries found that less than half had any type of ‘bridging’ relationship with policy-makers or programme managers (Lavis et al. 2010). Furthermore, researchers may underestimate the resources required to bring a new programme to scale. Likewise, most programme staff do not routinely read published reports of research or have experience integrating emerging research findings (Goldstein et al. 1998, Kelly et al. 2004, Lavis et al. 2006, Peterson et al. 2007). When they do attempt to adapt evidence-based interventions to local context, they may inadvertently neglect or revise components that are critical to their effectiveness.

To help facilitate the research-to-practice process, researchers, TA providers, recipients of TA, implementing agencies, and local communities should be viewed as one ‘boundary-spanning’ team that moves through the process together, always focused on the eventual utilisation of the research findings (Sogolow et al. 2000, Rogers 2002, Greenhalgh et al. 2004, Chinman et al. 2005, Lavis et al. 2006). This approach can help ensure that research meets the needs of programmes, without compromising study effectiveness. Once findings are available, the team can help facilitate integration of the findings into practice (World Health Organization 2004, Peterson et al. 2007). Experienced TA providers can also highlight programmatic issues that could be translated into future research questions that, if answered, could lead to more effective programmes. TA providers can facilitate lasting programme and research ‘exchange relationships’ that increase researchers’ credibility with programme staff, identify opportunities and capabilities for future studies, and increase willingness to participate in research (Logan et al. 2005, Blanchard and Aral 2010).

Cost-effectiveness

Costs for providing TA in developing countries vary substantially (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2007), but salary and travel costs for TA providers are the major expenses. However, the time and effort local programme staff exert to define TA needs and secure needed assistance can also add up (Florin et al. 2006).

Three approaches can be used to reduce TA costs and increase effectiveness. The first approach focuses TA efforts on a narrow range of evidence-based priorities decided using a collaborative process. This (rather than responding to all pull requests) will help ensure that interventions most likely to achieve key programme outcomes are well supported. Responding to all pull TA requests will not be cost-effective, and having a clear consensus on priorities will help control costs and increase the impact of the TA that is provided (Mitchell et al. 2002).

The second approach expands virtual TA programmes using emerging communication technologies such as distance learning, telephone consultation, mobile devices, texting systems and other Internet-based approaches to reduce personnel costs and travel expenses. This approach was used in several of the evaluations of TA we reviewed and appears feasible (Kelly et al. 2004, Marincioni 2007, Oliva et al. 2007). However, advances in computer and virtual technologies are evolving at such a fast pace that they need to be constantly monitored to identify new capabilities that can support TA systems.

The third approach transfers TA responsibilities from international staff to well-trained local staff. The cost of training and providing assistance through local TA providers is substantially lower than for international staff. Local TA providers are also more accessible and more likely to have direct knowledge of programme needs (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2007). However, local staff will need significant support to keep up on emerging research and innovative practices, and retaining them once they are trained and experienced can be a formidable challenge (Stevenson et al. 2002, Kegeles and Rebchook 2005, Oliva et al. 2007, Hunter et al. 2009).

Local TA systems can benefit from embedding experts with the required TA experience and skills into country teams (Rogers 2002, Meyerson et al. 2008). These experts can rapidly learn programme needs and gain local credibility more easily than TA providers who periodically visit. Resident experts can mentor the TA providers and help establish the systems needed to sustain local efforts. They can also serve as an interface between global information systems and ‘push’ efforts (World Health Organization 2004, Meyerson et al. 2008). If adequate provisions are made to sustain local TA infrastructure, embedding experts into country teams could be highly cost-effective in the long term. Such approaches may be required to build technical capacities in large-scale systems, such as that described earlier in the evaluation of TA in China (Tang et al. 2005).

The most cost-effective approach will likely be a permutation of the options. A well-designed ‘south-to-south’ TA capacity-building programme may tie together and strengthen all three options. Such programmes could identify common needs, provide peer mentoring to TA staff in neighbouring countries and create attractive career opportunities for local TA providers. Targeted assistance can still be obtained from international staff as needs emerge (CDC 2002).

Creating global TA systems

Creating and sustaining effective global TA systems to support the GHI or other global programmes is a formidable undertaking but will be fundamental to their success. Although priority should be given to strengthening the evidence based on TA effectiveness, the available literature is useful in guiding the development of TA systems. An ideal TA system must perform two critical functions. First, it must incorporate an in-depth knowledge of evolving programme needs and challenges. Second, it must continually and critically examine emerging knowledge, technologies and innovative practices to determine which are the most relevant, feasible and likely to improve programme effectiveness and capabilities.

A key task for TA systems will be to recruit, train, and retain skilled and experienced staff. This is especially true for local TA providers who, working with counterparts in other countries, can form a global community of TA practice. Assistance must be tailored to address local priorities, using cost-effective methods. The TA systems should link researchers to programmes to facilitate identifying research needs and translating research results in practice. Lastly, evaluating the quality, process, cost-effectiveness and impact of assistance must be an integral component of all TA systems. We believe the theory and evidence discussed here should stimulate the emergence of such systems - those that operate effectively at all levels (local, country, regional and global) and help achieve the world's health and development goals.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to recognize Kerry Aradhya for her editing of the essay and the assistance of Carol Manion, Library Services for providing consultation on the literature search and providing EndNote support. We would also like to recognize, Cathryn Jirlds who conceptualised and designed Figure 1 (A Dynamic TA System Model).

Development of this essay was supported in part through the Prevention Technologies (GHO-A-00-09-00016-00) and PROGRESS (GPO-A-00-08-0001-00) cooperative agreements with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

References

- Abdool Karim Q. Abdool Karim S.S. Frohlich J.A. Grobler A.C. Baxter C. Mansoor L.E. Kharsany A.B.M. Sibeko S. Taylor D. Al E. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329(5996):1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W.S. Del Rio C. HIV-associated resources on the internet. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2009;17(5):151–162. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/queryfcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20068262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer T.E. David S.L. Saucy G. Reviewing the behavioral science knowledge base on technology transfer. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1995. Monograph Series 155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;2(1):21–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor K. Robbins A. Freeman A.C. Dudley T. Phillips N. After the innovation: outcomes from the Texas behavioral data project. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(Suppl. 2):S71–S86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3946-8. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15933829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi S.M. Laga M. Bautista-Arredondo S. Coutinho A. Making HIV prevention programmes work. The Lancet. 2008;372(9641):831–844. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand IT. Diffusion of innovations and HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9(Suppl. 1):113–121. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard J. Aral S. Program science: an initiative to improve the planning, implementation and evaluation of HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention programmes. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2010;87(1):2–3. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. South-to-south collaboration: lessons learned. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. Available from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACT829.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M. Hunter S.B. Ebener P. Paddock S.M. Stillman L. Imm P. Wandersman A. The getting to outcomes demonstration and evaluation: an illustration of the prevention support system. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):206–224. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9163-2. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18278551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M. Hannah G. Wandersman A. Ebener P. Hunter S.B. Imm P. Sheldon I. Developing a community science research agenda for building community capacity for effective preventive interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35(3–4):143–157. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3390-6. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15909791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry L. Luong M. Krumholz H. Gaddis X. Kennedy P. Rulisa S. Taylor L. Bradley E. Achieving large ends with limited means: grand strategy in global health. International Health: Lancet. 2010;10:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J.A. Dupre E.P. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18322790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R. Jumper-Thurman P. Plested B. Oetting E. Swanson L. Community readiness: research to practice. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(3):291–307. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K.M. Geller A.C. Viswanath V. Rutsch L. Zwirn X. Gorham S. Puleo E. The sunwise policy intervention for school-based sun protection: a pilot study. Journal of School Nursing. 2008;24(4):215–221. doi: 10.1177/1059840508319627. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18757354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M.E. Ridenour T.A. Greenberg M.T. The longitudinal effect of technical assistance dosage on the functioning of communities that care prevention boards in Pennsylvania. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2008;29(2):145–165. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0130-3. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18365313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin P. Celebucki C. Stevenson X. Mena X. Salago D. White A. Harvey B. Dougal M. Cultivating systemic capacity: the Rhode Island tobacco control enhancement project. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;38(3):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates R.M. Helping others defend themselves: the future of U.S. Security assistance. Foreign Affairs. 2010;89(3):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs D.A. Hawkins S.R. Clinton-Sherrod A.M. Noonan R.K. Empowering programs with evaluation technical assistance: outcomes and lessons learned. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10(Suppl. 1):38S–44S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908316517. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/queryfcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19136444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein E. Wrubel X. Faigeles B. Decarlo P. Sources of information for HIV prevention program managers: a national survey. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10(1):63–74. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9505099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office & President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief. Efforts to align programs with partner countries’ HIV/AIDS strategies and promote partner country ownership. Washington, DC: United States Government Accountability Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T. Robert G. Macfarlane F. Bate P. Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15595944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshbarger C. Simmons G. Coelho H. Sloop K. Collins C. An empirical assessment of implementation, adaptation, and tailoring: the evaluation of CDC's national diffusion of voices/voces. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(suppl):184–197. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S.B. Chinman M. Ebener P. Imm P. Wandersman A. Ryan G.W. Technical assistance as a prevention capacity-building tool: a demonstration using the getting to outcomesframework. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(5):810–828. doi: 10.1177/1090198108329999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly D. Gibbs D. Napp D. Westover B. Uhl G. Technical assistance for the evaluation of community-based HIV prevention programs. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(5):550–563. doi: 10.1177/1090198103254346. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=>Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>14582597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S.C. Hudd K. Diberto G. Operational fidelity to an evidence-based HIV prevention intervention for people living with HIV/AIDS. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31(4):235–245. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0217-5. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20582629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles S.M. Rebchook G.M. Challenges and facilitators to building program evaluation capacity among community-based organizations. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(4):284–299. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.4.284. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>16178701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M. Redmon P. Using technical assistance to strengthen tobacco control capacity: evaluation findings from the tobacco technical assistance consortium. Public Health Reports. 2006;121(5):547. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.A. Heckman T.G. Stevenson L.Y. Williams P.N. Ertl T. Hays R.B. Leonard N.R. O'donnell L. Terry M.A. Sogolow E.D. Neumann M.S. Transfer of research-based HIV prevention interventions to community service providers: fidelity and adaptation. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(Suppl. 5):87–98. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>11063072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.A. Somlai A.M. Benotsch E.G. Mcauliffe T.L. Amirkhanian Y.A. Brown K.D. Stevenson L.Y. Fernandez M.I. Sitzler C. Gore-Felton C. Pinkerton S.D. Weinhardt L.S. Opgenorth K.M. Distance communication transfer of HIV prevention interventions to service providers. Science. 2004;305(5692):1953–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.1100733. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>15448268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J. Guindon G. Cameron D. Boupha B. Dejman D. Osei E. Sadana R. Bridging the gaps among research, policy and practice in low-and middle-income countries: a survey of researchers. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2010;182(9):E350–E361. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J. Lomas J. Hamid M. Sewankambo N. Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84:620–628. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leviton L. Theoretical foundations of AIDS-prevention programs, Chapter 3. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Logan J. Beatty M. Woliver R. Rubinstein E. Averbach A. Creating a bridge between data collection and program planning: a technical assistance model to maximize the use of HIV/AIDS surveillance and service utilization data for planning purposes. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(Suppl. B):68–78. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.Supplement_B.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marincioni F. Information technologies and the sharing of disaster knowledge: the critical role of professional culture. Disasters. 2007;31(4):459–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01019.x. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/queryfcgi?cmd=>Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>18028164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry R.M. Daniels P. Yancey E.M. Akintobi T.H. Berry J. Clark N. Dawaghreh A. Enhancing community-based organizations’ capacity for HIV/AIDS education and prevention. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2009;32(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.01.002. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>19376579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson B. Martich F. Naehr G. Ready to go: the history and contributions of U.S. Public health advisors. Research Triangle Park, NC: American Social Health Association; 2008. pp. 163–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. Synthesis of evaluations on technical assistance: evaluation study 2007/2. Copenhagen, Denmark: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R.E. Florin P. Stevenson J.F. Supporting community-based prevention and health promotion initiatives: developing effective technical assistance systems. Health Education & Behavior. 2002;29(5):620–639. doi: 10.1177/109019802237029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R. Stone-Wiggins B. Stevenson J.S. Florin P. Cultivating capacity: outcomes of a statewide support system for prevention coalitions. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2004;27(2):67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D. Liberati A. Tetzlaff J. Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19621072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld G.R. Technical assistance systems in human services: an overview. In: Sturgeon MLT S., editor; Ziegler A., editor; Neufield R., editor; Wiegerink and R., editor. Technical assistance: facilitating change. Bloomington: Developmental Training Center, Indiana University; 1978. pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Annex: Paris declaration on aid effectiveness and the accra agenda for action: ownership, harmonisation, alignment, results and mutual accountability. OECD; 2010. Available from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/30/63/43911948.pdf [Accessed 4 August 2011] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva G. Rienks J. Chavez G.F. Evaluating a program to build data capacity for core public health functions in local maternal child and adolescent health programs in California. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2007;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0139-2. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/queryfcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>17006772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padian N.S. Holmes C.B. Mccoy S.I. Lyerla R. Bouey P.D. Goosby E.P. Implementation science for the US President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR) Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2011;56(3):199–203. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bb448. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21239991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajares F. Overview of social cognitive theory and of self-efficacy. 2002. Available from http://www.emoryedu/EDUCATION//mfp/effhtml [Accessed 2 January 2010]

- Peterson J.C. Rogers E.M. Cunningham-Sabo L. Davis S.M. A framework for research utilization applied to seven case studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(Suppl. 1):S21–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. Brough R. Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy and Planning. 2004;19(5):336–345. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh038. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15310668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. Diclemente C. Norcross J. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 1993;5(1):2–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs N.R. Nakawatase M. Pentz M.A. Promoting community coalition functioning: effects of project step. Prevention Science. 2008;9(2):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer B.K. Glanz K. Rasband G. Searching for evidence about health education and health behavior interventions. Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28(2):231–248. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E. The nature of technology transfer. Science Communication. 2002;23(3):323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E.M. A prospective and retrospective look at the diffusion model. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9(Suppl. 1):13–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach L.A. Gunning M. Sun P. Sussman S. The project towards no drug abuse (TND) dissemination trial: implementation fidelity and immediate outcomes. Prevention Science. 2010;11(1):77–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0151-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogolow E.D. Kay L.S. Doll L.S. Neumann M.S. Mezoff J.S. Eke A.N. Semaan S. Anderson J.R. Strengthening HIV prevention: application of a research-to-practice framework. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(Suppl. 5):21–32. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=>11063067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R. Clair S. Greenberg M. Redmond C. Shin C. Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):137–146. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.137. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17605536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson J. Florin P. Mills D. Andrade M. Building evaluation capacity in human service organizations: a case study. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2002;25(3):233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Tang K.C. Nutbeam D. Kong L. Wang R. Yan J. Building capacity for health promotion-a case study from China. Health Promotion International. 2005;20(3):285–295. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai003. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15788525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Global Fund. Principles for technical support. 2010. Available from http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/rounds/9/TechnicalSupportPoster_en.pdf [Accessed 7 March 2011]

- Tyson S. Mcneil M. How to… provide effective technical assistance. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;116(s1):93–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. ‘Three ones’ key principles. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. ‘Coordination of national responses to HIV/AIDS’ guiding principles for national authorities and their partners. [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Implementation of the global health initiative: consultation document. Washington, DC: United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Remarks by Dr. Rajiv Shah, administrator USAID: the modern development enterprise (speech). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Valente T.W. Rogers E.M. The origins and development of the diffusion of innovations paradigm as an example of scientific growth. Science Communication. 1995;16(3):242–273. doi: 10.1177/1075547095016003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Linking research to action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]