Abstract

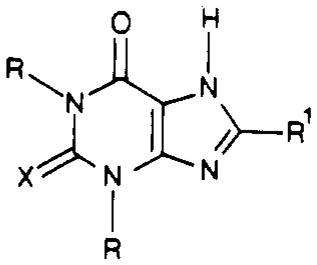

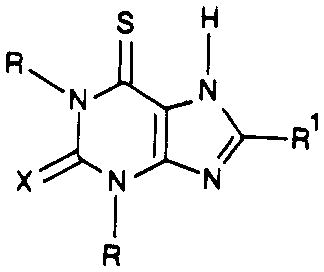

Sulfur-containing analogues of 8-substituted xanthines were prepared in an effort to increase selectivity or potency as antagonists at adenosine receptors. Either cyclopentyl or various aryl substituents were utilized at the 8-position, because of the association of these groups with high potency at A1-adenosine receptors. Sulfur was incorporated on the purine ring at positions 2 and/or 6, in the 8-position substituent in the form of 2- or 3-thienyl groups, or via thienyl groups separated from an 8-aryl substituent through an amide-containing chain. The feasibility of using the thienyl group as a prosthetic group for selective iodination via its Hg2+ derivative was explored. Receptor selectivity was determined in binding assays using membrane homogenates from rat cortex [[3H]-N6-(phenylisopropyl) adenosine as radioligand] or striatum [[3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine as radioligand] for A1- and A2-adenosine receptors, respectively. Generally, 2-thio-8-cycloalkylxanthines were at least as A1 selective as the corresponding oxygen analogue. 2-Thio-8-aryl derivatives tended to be more potent at A2 receptors than the oxygen analogue. 8-[4-[(Carboxymethyl)oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropyl-2-thioxanthine ethyl ester was >740-fold A1 selective.

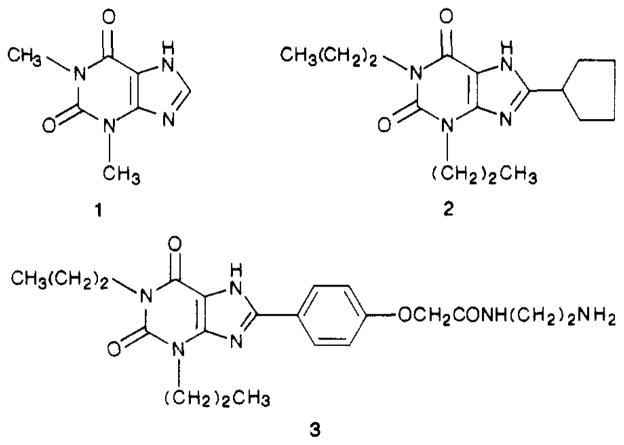

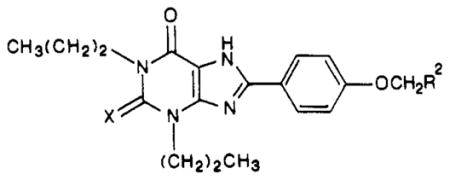

1,3-Dialkyl and other xanthine derivatives inhibit many of the pharmacological and physiological effects of adenosine, e.g., the cardic-depressive,1 hypotensive,1 antidiuretic,2 and antilipolytic effects,3 by acting as competitive antagonists at A1- and A2-adenosine receptor subtypes. The naturally occurring caffeine and theophylline (1; Figure 1) are the most widely used xanthine drugs. However, they are nonselective and relatively weak adenosine antagonists (Ki values of 10 μM or greater). Synthetic analogues of theophylline, containing 1,3-dipropyl, 8-aryl, and 8-cycloalkyl substitutions, are more potent as adenosine antagonists.4–6 The combination of 1-, 3-, and 8-position substitutions has resulted in analogues such as 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine5,6 (CPX; 2) and 8-[4-[[[[(2-aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine7 (XAC; 3) which are more than 4 orders of magnitude more potent than theophylline in binding at A1-adenosine receptors, and which are A1-selective by factors of 300 and 60, respectively.

Figure 1.

Xanthines having thio substitutions at the 2- and/or 6-position have been reported to act as antagonists at A2 receptors in human fibroblasts21 and as phosphodiesterase inhibitors with potency comparable to or greater than that of theophylline.8,9a Remarkably, 6-thiocaffeine and 6-thiotheophylline cause cardiac depression rather than stimulation.9b Recently, 6-thiocaffeine and 6-thiotheophylline were reported to induce tracheal relaxation, without cardiac or behavioral stimulation.9a Thio substitution of the NH at position 7 of 8-phenyltheophylline reduced activity by 1000-fold at an A1 receptor and by nearly 100-fold at an A2 receptor.20

Results

Chemistry

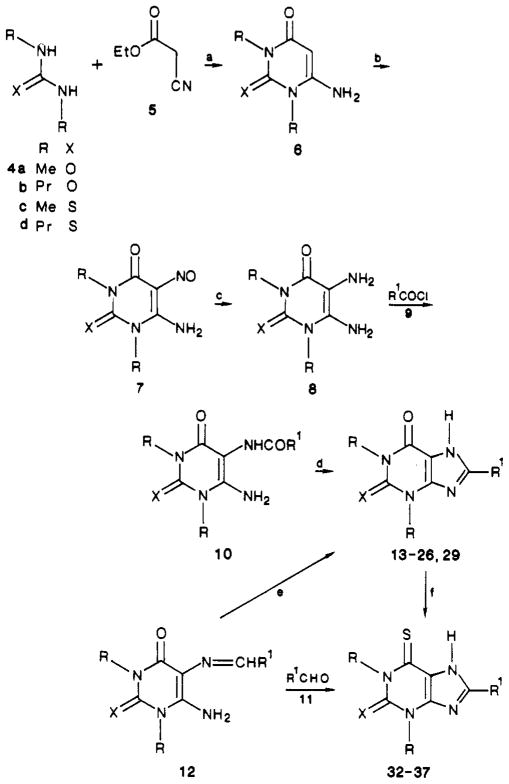

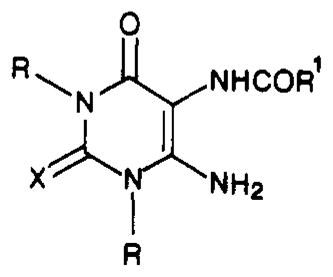

Various 8-substituted xanthine and thioxanthine derivatives were synthesized via 1,3-dialkyl-5,6-diaminouracils as shown in Scheme I. The substituted uracil and 2-thiouracil intermediates were prepared via an optimized Traube synthesis.6,7a 1,3-Dimethyl- and 1,3-di-n-propyl-5,6-diaminouracil and their 2-thio derivatives were obtained by condensation of the corresponding dialkyl urea (4a and -b) or thiourea (4c and -d) with ethyl cyanoacetate (5). The products after ring closure, substituted 6-aminouracil derivatives 6, were then nitrosated at the 5-position. The nitroso group was reduced through chemical reduction or catalytic hydrogenation to form the intermediate 1,3-dialkyl-5,6-diaminouracil derivatives 8 in good yield.

Scheme I.

The next step of the synthesis was to form the imidazole ring of the purine nucleus, resulting in the xanthine derivatives, as listed in Table I (compounds 1, 2, and 13–28). The more nucleophilic 5-amino group of compound 8 was acylated by using a carboxylic acid chloride 9, forming the 1,3-dialkyl-5-(acylamino)-6-aminouracil derivatives 10. 1,3-Dialkyl-5-(acylamino)-6-aminouracils derived from thiophene-2-carboxylic acid and -3-carboxylic acid chlorides and from cyclopentanecarboxylic acid chloride were isolated and characterized (Table II). The various 1,3-dialkyl-5-(acylamino)-6-aminouracil derivatives were then cyclized to the corresponding xanthine and 2-thioxanthine derivatives (Table III) by treatment with aqueous sodium hydroxide.

Table I.

Potencies of Xanthine Derivatives at Adenosine A1 and A2 Receptors in Nanomolar Concentration Unitsa,b

| compd | R | R1 | X |

|

Ki(A2)/Ki(A1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (A1 receptors) | Ki (A2 receptors) | |||||

| 1a | Me | H | O | 8470 ± 1490c | 25300 ± 2000a | 2.99 |

| 1b | Pr | H | O | 450 ± 25c | 5160 ± 590c | 11.5 |

| 2a | Me | cyclopentyl | O | 10.9 ± 0.9c | 1440 ± 70c | 133 |

| 2b | Pr | cyclopentyl | O | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 410 ± 40 | 455 |

| 13 | Me | cyclopentyl | S | 10.2 ± 1.5 | 1390 ± 88 | 136 |

| 14 | Pr | cyclopentyl | S | 0.655 ± 0.058 | 314 ± 62 | 479 |

| 15a | Me | 2-furyl | O | 350 ± 20c | 2780 ± 50c | 7.94 |

| 15b | Pr | 2-furyl | O | 37 ±6 | 640 ± 100 | 16.8 |

| 15c | Me | 2-furyl | S | 182 ± 36 | 4450 ± 420 | 10.6 |

| 15d | Pr | 2-furyl | S | 32 ± 5 | 594 ± 71 | 18.6 |

| 16 | Me | 3-furyl | O | 72.4 ± 3.7c | 984 ± 70c | 13.6 |

| 17 | Me | 2-thienyl | O | 233 ± 48.6 | 1630 ± 179 | 6.97 |

| 18 | Me | 3-thienyl | O | 152 ± 27 | 841 ± 109 | 5.53 |

| 19 | Pr | 2-thienyl | O | 16.1 ± 1.96 | 381 ± 27.7 | 23.6 |

| 20 | Pr | 3-thienyl | O | 10.0 ± 0.03 | 121 ± 18.2 | 12.1 |

| 21 | Me | 2-thienyl | S | 221 ± 43.3 | 1740 ± 153 | 7.87 |

| 22 | Pr | 2-thienyl | S | 35.1 ± 6.0 | >5000 | >142 |

| 23 | Me | phenyl | O | 86.0 ± 2.8c | 848 ± 115c | 9.85 |

| 24 | Et | phenyl | O | 44.5 ± 1.2c | 836 ± 73c | 19.4 |

| 25 | Pr | phenyl | O | 10.2 ± 2.6c | 180 ± 29c | 17.8 |

| 26a | Me | phenyl | S | 38 ± 6 | >7000 | >184 |

| 26b | Pr | phenyl | S | 16.1 ± 2 | 422 ± 33 | 26.1 |

| compd | R2 |

|

Ki (A2)/Ki (A1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Ki (A1 receptors) | Ki (A2 receptors) | |||

| 27 | COOH | O | 58 ± 3 | 2200 ± 526 | 37.8 |

| 28 | COOH | S | 53.8 ± 7.1 | 315 ± 60.8 | 5.86 |

| 29 | COOEt | O | 42 ± 3 | >5000 | >119 |

| 30 | COOEt | S | 6.78 ± 0.64 | >5000 | >740 |

| 3 | CONH(CH2)2NH2 | O | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 63 ± 21 | 52.5 |

| 31 | CONH(CH2)2NH2 | S | 2.69 ± 0.77 | 26.3 ± 1.76 | 9.8 |

| 32 | CONH(CH2)2NHCH3 | O | 15.1 ± 1.6d | [9.3 ± 2.1]f | [0.62] |

| 33 | CONH(CH2)2NHCH3 | S | 2.4 ± 0.28 | 6.80 ± 1.36 | 2.8 |

| 34 | CONH(CH2)2N(CH3)2 | O | 2.8 ± 0.19d | 5.03 ± 0.54 | 1.8 |

| 35 | CONH(CH2)2N(CH3)2 | S | 2.55 ± 0.60 | 27.9 ± 7.5 | 11 |

| 36 | CON(CH3)(CH2)2N(CH3)2 | O | 0.93 ± 0.03d | 6.26 ± 0.25 | 6.7 |

| 37 | CON(CH3)(CH2)2N(CH3)2 | S | 2.57 ± 0.67 | 24.5 ± 8.4 | 9.5 |

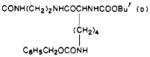

| 38 |

|

O | 12 | e | e |

| 39 |

|

S | 84 | 870 | 10 |

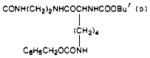

| 40 |

|

O | 6.4 ± 2.7 | 191 ± 13 | 30 |

| 41 |

|

S | 8.9 | 322 ± 17 | 36 |

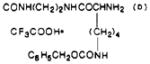

| 42 |

|

O | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 180 | 210 |

| 43 |

|

S | 13.0 ± 3.5 | 46.8 ± 9.4 | 3.6 |

| 44 |

|

O | 3.69 ± 0.71d | 207 ± 57d | 56 |

| 45 |

|

S | 33.5 | e | e |

| 46 |

|

O | 18.3 ± 3.0 | 147 ± 5 | 8.1 |

| 47 |

|

O | 16.2 ± 2.7 | 458 ± 34 | 28.3 |

| 48 |

|

O | 11.3 ± 1.5 | 116 ± 25 | 10.3 |

| 49 |

|

O | 7.44 ± 0.98 | 630 ± 160 | 85 |

| 50 |

|

O | 17 ± 1.6 | e | e |

| 51 |

|

O | 1.3 ± 0.12 | e | e |

| compd | R | R1 |

|

Ki (A2 receptors) | Ki(A2)/Ki(A1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Ki (A1 receptors) | |||||

| 52 | Me | cyclopentyl | S | 40.5 ± 6.6 | 11500 ± 628 | 285 |

| 53 | Pr | cyclopentyl | S | 4.87 ± 0.82 | 2780 ± 730 | 572 |

| 54 | Me | cyclopentyl | O | 202 ± 26 | 8980 ± 1300 | 44.4 |

| 55 | Pr | cyclopentyl | O | 15.5 ± 1.5 | 3360 ± 270 | 217 |

| 56 | Me | phenyl | O | 1380 ± 74 | 11300 ± 777 | 8.18 |

| 57 | Et | phenyl | O | 1010 ± 321 | 3510 ± 290 | 3.47 |

Ki value from a single determination run in triplicate or average of three ± SEM.

Inhibition of binding of [3H](phenylisopropyl)-adenosine to A1 receptors in rat cortical membranes and binding of [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine to A2-adenosine receptors in rat striatal membranes was measured as described.18,19

Values taken from Bruns et al.18

Values taken from Jacobson et al.10

Not determined.

Kb for inhibition of 5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine-stimulated adenylate cyclase, in pheochromocytoma PC12 cell membranes.10b

Table II.

Synthesis and Characterization of 1,3-Dialkyl-5-(acylamino)-6-aminouracils

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R | R1 | X | % yield | mp, °C | formula | anal. |

| 10a | Me | cyclopentyl | S | 71 | 253 | C12H18N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 10b | Pr | cyclopentyl | S | 92 | 103 | C16H26N4O2S·H2O | C, H, N |

| 10c | Me | 2-thienyl | O | 76 | >300 | C11H12N4O3S | C, H, N |

| 10d | Me | 3-thienyl | O | 78 | >300 | C11H12N4O3S | C, H, N |

| 10e | Pr | 2-thienyl | O | 88 | 143 | C15H20N4O3S | C, H, N |

| 10f | Pr | 3-thienyl | O | 88 | 144 | C15H20N4O3S | H, N; Ca |

| 10g | Me | 2-thienyl | S | 83 | >300 | C11H12N4O2S2 | C, H, N |

| 10h | Pr | 2-thienyl | S | 80 | 150 | C15H20N4O2S2 | C, H, N |

C: calcd, 53.56; found, 52.95.

Table III.

Synthesis and Characterization of Xanthine Derivatives

| compd | % yield | mp, °C | formula | anal. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 91 | 278 | C12H16N4OS | C, H, N |

| 14 | 89 | 217 | C16H24N4OS | C, H, N |

| 15a | 80 | 347 | C11HI0N4O3 | C, H, N |

| 15b | 88 | 252 | C15H18N4O3 | C, H, N |

| 15c | 85 | >350 | C11H10N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 15d | 88 | 269 | C15H18N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 17 | 82 | >300 | C11H10N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 18 | 92 | >300 | C11H10N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 19 | 85 | 259 | C15H18N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 20 | 87 | 267 | C15H18N4O2S | C, H, N |

| 21 | 71 | >340 | C11H10N4O2S2 | C, H, N |

| 22 | 92 | 298 | C15H18N4OS2 | C, H, N |

| 26a | 91 | >350 | C13H12N4OS | C, H, N |

| 26b | 80 | 253 | C17H20N4OS | C, H, N |

| 33 | 95 | 206–208 | C22H30N6O3S·¼H2O | C, H, N |

| 35 | 93 | 238–240 | C23H32N6O3S·¾H2O | C, H, N |

| 37 | 52 | 172–174 | C24H34N6O3S·½H2O | C, H, N |

| 39 | 92 | 210–212 | C40H54N8O8S | C, H, N |

| 41 | 84 | 182–187 | C37H47F3N8O8S·½CF3COOH·½H2O | C, H, N |

| 43 | 97 | 238–242 dec | C27H40N8O4S·3HBr·3/2H2O | C, H, N |

| 45 | 68 | 160–168 | C33H43N7O8S | C, H, Nb |

| 48 | 85 | 240 dec | C27H31N6O5SI·2.5H2O | C, H, N |

| 52 | 85 | 236 | C12H16N4S2 | C, H, N |

| 53 | 84 | 135 | C16H24N4S2 | C, H, N |

| 54 | 79 | 241 | C12H16N4OS | C, H, N |

| 55 | 81 | 153 | C10H24N4OS | C, H, N |

| 56 | 84 | 256 | C13H12N4OS | C, H, N |

| 57 | 72 | 223 | C15H16N4OS | H, C, Na |

| 60b | 84 | 230 | C11H9NO3SHg | C, H, N |

| 61a | 43 | 71–73 | C6H5O2SI·0.5H2O | C, H |

C: calcd, 59.32; found, 58.52. N: calcd, 18.65; found, 18.12.

N: calcd, 14.05; found, 15.42.

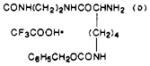

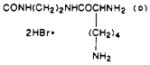

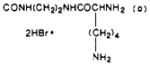

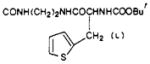

For 8-[p-[(carboxymethyl)oxy]phenyl]xanthine derivatives related to a xanthine amine congener, compound 3, an alternate route was used to form the imidazole ring. 1,3-Dipropyl-5,6-diaminouracil (8b) or the corresponding 2-thiouracil (8d) was condensed with [(p-formylphenyl)-oxy]acetic acid, forming the imine 12. Upon oxidation, the carboxylic acid congeners 27 (XCC) and 28 were obtained. The xanthine carboxylic acid derivatives were then esterified, giving the ethyl esters 29 and 30, respectively, which were treated with neat ethylenediamine as previously reported7 to give the amine derivatives 3 and 31. Since the A2 potency of compound 31 was enhanced over the oxygen analogue (see below), compound 3, we synthesized other 8-aryl-2-thioxanthine derivatives in an effort to increase A2 potency. Other amine derivatives were synthesized through aminolysis reactions (compounds 32–35) or by carbodiimide coupling (compounds 36–39) as reported.10b Lysyl conjugates 38–43 were prepared as described.10c

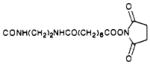

An N-hydroxysuccinimide ester derivative, 44, was reported to be an irreversible inhibitor of A1-adenosine receptors at concentrations greater than 50 nM.10a If shown to be a potent and nonselective adenosine antagonist, this xanthine may be a potential inhibitor of both A1- and A2-adenosine receptors. Certain isothiocyanate-containing xanthines related to compound 3 also have been shown to be chemically reactive with A1 receptors.10a Efforts to synthesize analogous xanthine–isothiocyanates containing the 2-thio substitution were unsuccessful, likely due to side reactions involving the more reactive thio group.

A thiation reaction was used to generate 6-thioxanthine derivatives from the corresponding oxygen analogues. It is known11 that xanthine derivatives are preferentially thiated at the 6-position with P4S10. Dioxane was the favored reaction medium to give high yields of the anticipated 6-thio- and 2,6-dithioxanthines (compounds 52–57). For example, CPX was converted to 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropyl-6-thioxanthine (55) by using this thiation reaction.

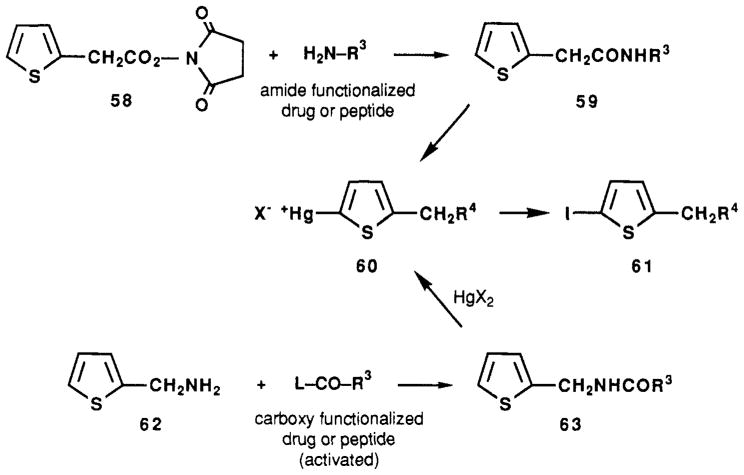

Iodinated xanthine derivatives, synthesized by using a prosthetic group12 or by classical methodology, have been introduced as high-affinity radioligands for adenosine receptors.12,13 We have explored the use of a 2-thienyl substituent as a site for selective iodination, via mercuration (Scheme II). These substituted thiophene derivatives, such as 59 and 63, undergo regioselective mono-mercuration at the unsubstituted 2-position, rapidly and at ambient temperature, in the presence of stoichiometric quantities of mercury salts such as mercuric acetate.14 The 2-mercuriothiophene salt 60 is then exposed to elemental iodine, resulting in the corresponding 2-iodothiophene derivative 61.

Scheme II.

Use of 2-Thienyl Derivatives as Prosthetic Groups for Mercuration and Subsequent Iodinationa

aL = leaving group, such as N-hydroxysuccinimide.

New prosthetic groups designed for facile radiodination of functionalized drugs and peptides are still being sought.15,16 We have used thiophene-2-acetic acid (as its reactive N-hydroxysuccinimde ester, 58) and thiophene-2-methanamine (62) as prosthetic groups for iodination, via mercuration.

Compound 58 reacted with XAC (3) to form an amide, compound 46. This xanthine bearing a 2-alkylthienyl prosthetic group was readily mercurated to give 47.

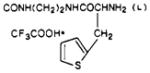

Iodination via 2-mercuriothiophene intermediates as in Scheme II may be carried out selectively in the presence of other susceptible aromatic groups, such as phenols. Compound 58 reacted with L-tyrosylglycine to form an amide [compound 59, in which R3 = CH(CH2C6H4OH)-CONHCH2COOH]. Upon sequential treatment with mercuric acetate and iodine (1 equiv), the corresponding monoiodinated peptide derivative, 61 [R4 = CONHCH-(CH2C6H4OH)CONHCH2COOH], was obtained in high yield.

The N-succinoyl derivative [63a; R3 = (CH2)2COOH] of thiophene-2-methanamine was mercurated to form an internal salt, 60b [R4 = NHCO(CH2)2COOH] which precipitated from methanol. Upon treatment with iodine an immediate reaction occurred. This reaction was followed by NMR in DMSO-d6. The complete reaction of the 2-mercuriothiophene derivative was indicated by shifts of the thiophene aromatic signals to 6.68 and 7.13 ppm from TMS, corresponding to the 2-iodo derivative 61b.

Pharmacology

Affinity at A1- and A2-adenosine receptors was measured in competitive binding assays, using as radioligands [3H]-N6-(phenylisopropyl)adenosine17 (with rat cerebral cortical membranes) and [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine (with rat striatal membranes),18 respectively.

A sulfur substitution at the 2-position carbonyl group of 1,3-dialkylxanthines usually did not decrease the affinity of the xanthines for A1- or A2-adenosine receptors. In the case of the 2-thio analogue of CPX, compound 14, the A1 affinity was enhanced by the thio substitution. The 2-thioxanthine amine congener, compound 30, bound with greater affinity at A2 receptors and with less affinity at A1 receptors than the corresponding oxygen analogue, compound 3. Potency at A2 receptors was enhanced 7-fold by the 2-thio substitution in the case of a carboxylic acid congener (compounds 27 and 28).

N-Methylated analogues (32–37) of compound 31 were prepared. As in the 2-oxo series, the secondary N-methylamine derivative 33 was the most potent at A2 receptors with a Ki value of 6.8 nM. Thus, the combination of two modifications of compound 3 enhanced its A2 affinity 10-fold.

A sulfur substitution at the 6-position carbonyl group of 1,3-dialkylxanthines was not well tolerated at either A1 or A2 binding sites. Thus, the 6-thio analogue of CPX 55 was 17-fold less potent than CPX at A1 receptors. The 6-thio analogue of 1,3-diethyl-8-phenylxanthine (57) was 23-fold less potent than DPX (24) at A1 receptors and 12-fold less potent at A2 receptors. 2,6-Dithio analogues, such as 53, were intermediate in potency between the corresponding 2-thio and 6-thio analogues.

Substitutions of thienyl and furyl groups at the 8-position of xanthines have approximately equivalent effects on affinity at both receptor subtypes. Both substitutions are generally slightly less potent than the corresponding 8-phenylxanthine analogues. For both thienyl and furyl derivatives (several of which were reported previously, by Bruns et al.18), attachment at the 3-position relative to the heteroatom (sulfur or oxygen, respectively) results in greater potency at adenosine receptors than attachment at the 2-position. Preference for 3-thienyl derivatives was evident, particularly at the A2 subtype (cf. 18 vs 17 and 20 vs 19).

1,3-Dipropyl-8-(2-thienyl)-2-thioxanthine (22) did not bind measurably to A2 receptors at its limit of aqueous solubility. At pH 7.7 in Tris buffer this concentration was 5.8 μM, determined with a log ε for absorption in methanol at 320 nm of 4.38. At this concentration there was not even a partial displacement of tritiated [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine from striatal membranes. Thus, compound 22 was > 142-fold A1 selective in these binding assays. Compound 30 is > 740-fold A1 selective, but low solubility may limit its usefulness. The aqueous solubilities of A1-selective xanthines 26a and 30 are 9.0 and 5.4 μM, respectively.

Discussion

We have found that 2-thioxanthines are very similar in potency to the corresponding oxygen analogues. In certain cases, as for the CPX analogue 14 and an 8-(2-thienyl) derivative, 22, a greater margin of A1 selectivity may be achieved by using the 2-thio substitution. A 6-thio substitution is not well tolerated at either A1 or A2 receptors.

The feasibility of using a 2-thienyl moiety as a prosthetic group for selective iodination via its Hg2+ derivative was explored. By facile and selective mercuration at the 2-thienyl ArH, a site for rapid and regioselective (in the presence of phenols) iodination is created. A xanthine conjugate of XAC and thiophene-2-acetic acid was sequentially mercurated and iodinated by this scheme, resulting in an iodinated xanthine with potential use as an antagonist radioligand for adenosine receptors. This scheme may have applicability to other receptor ligands, including tyrosyl peptides, in which iodination in the presence of essential phenolic groups is desired.

Experimental Section

8- [4- [[[[(2–Aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine (XAC; xanthine, amine congener), 2-chloroadenosine, and 8-cyclohexyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine were obtained from Research Biochemicals, Inc. (Natick, MA). Compounds 32, 34, 36, 38,42, 50, and 51 were reported previously.7c,10b Amino acid derivatives of XAC and the 2-thio analogue were synthesized in the manner previously described,7c using the water-soluble 1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDAC) in dimethylformamide. [(p-Formylphenyl)oxy]acetic acid was obtained from Eastman Kodak (Rochester, NY). [3H]-N6-(Phenylisopropyl)adenosine and [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine were from Du Pont NEN Products, Boston, MA. Thiophene-2-acetic acid was from Aldrich.

New compounds were characterized by 300-MHz proton NMR (unless noted, chemical shifts are in DMSO-d6 in ppm from TMS), chemical ionization mass spectroscopy (CIMS, NH3, Finnigan 1015 spectrometer), and C, H, and N analysis. UV spectra were measured in methanol, and the results are expressed as peak wavelengths in nanometers with log ε values in parentheses.

General Procedure for Compound 10

A 1,3-disubstituted 5,6-diaminouracil or the corresponding 1-thiouracil (10 mmol) was suspended in 10 mL of absolute pyridine, and then under stirring 11 mmol of the acid chloride (freshly prepared) was added dropwise. After 5-h stirring at room temperature, the reaction mixture was poured slowly into 100 mL of H2O, and the precipitate was collected by suction filtration. Purification was done by recrystallization from a EtOH/H2O mixture. Yields ranged from 70 to 90%.

General Procedure for Compounds 13–26

A 1,3-disubstituted 5-(acylamino)-6-aminouracil or the corresponding 2-thiouracil (10 mmol) was heated under reflux in a mixture of 40 mL of 1 N NaOH and 10 mL of EtOH for 1 h. The hot solution was acidified with acetic acid, resulting in the formation of a precipitate upon cooling. The precipitate was collected and recrystallized from a H2O/EtOH mixture: yield 80–90% of colorless crystals; 1H NMR spectrum (compound 13) δ 3.86 (3 H, s, CH3), 3.68 (3 H, s, CH3), 3.19 (m, 1 H, cyclohex C1), 2.0 (m, 2 H, cyclohex C2 and C5), 1.6–1.8 (m, 6 H, cyclohex). The NMR spectra of the other compounds were consistent with the assigned structures.

8-[4-[[[[N-[2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl]-N-methylamino]-carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-2-thio-1,3-dipropylxanthine (37)

8-[4-[(Carboxymethyl)oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropyl-2-thioxanthine (compound 28; 21 mg, 52 μmol), N,N,N′-trimethyl-ethylenediamine (Aldrich, 20 mg, 0.20 mmol), EDAC (45 mg, 0.23 mmol), and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt; 25 mg, 0.18 mmol) were combined in 1 mL of DMF. After stirring overnight, 0.5 mL of sodium carbonate (pH 10, 0.5 M) and 2 mL of saturated NaCl were added. After cooling overnight, a white precipitate was collected, yield 13 mg (52%). The NMR and mass spectra were consistent with the assigned structure.

8-[4-[[[[[2-[[[6-[(N-Succinimidyloxy)carbonyl]-n-hexyl]carbonyl]amino]ethyl]amino]carbonyl]methyl]-oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropyl-2-thioxanthine (45)

Compound 31 (10.4 mg, 0.024 mmol) was added to a solution of disuccinimidyl suberate (13.1 mg, 0.036 mmol; Pierce, Rockford, IL) in DMF (1 mL) and vigorously stirred for 2 h or until complete by TLC (CHCl3/MeOH/AcOH, 18/1/1). Dry ether (2 mL) was then added to the suspension followed by the addition of petroleum ether until cloudy. The suspension was allowed to stand at 0 °C for 1 h and then filtered to give an off-white powder: yield 11.5 mg (68%); mp 160–168 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) 0.90 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.28 (br m, 4 H), 1.44 (m, 2 H), 1.71 (m, 2 H), 1.83 (m, 2 H), 1.83 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.65 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.79 (s, 4 H), 3.15 (br s, 4 H), 3.32 (s, H2O), 4.45 (br t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 4.54 (s, 2 H), 4.59 (br t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.83 (br s, 1 H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 8.18 (br s, 1 H).

General Procedure for 6-Thiation Reaction

The appropriate xanthine or 2-thioxanthine derivative (10 mmol) was heated with 6 g of P4S10 in 100 mL of dioxane for 3–5 h under reflux. Insoluble material was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was added dropwise to 200 mL of H2O with stirring. The precipitate was collected and purified by recrystallization from a H2O/EtOH mixture; yield 80–85%.

N-Succinimidyl Thiophene-2-acetate (58)

Thiophene-2-acetic acid (1.61 g, 11 mmol), dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (2.34 g, 11 mmol), and N-hydroxysuccinimide (1.30 g, 11 mmol) were added to 50 mL of ethyl acetate containing 10% DMF. After stirring for 2 h, the urea was removed by filtration. The filtrate was washed with aqueous acid/base and evaporated. The residue was recrystallized from ethyl acetate/petroleum ether; yield 2.01 g (74%), mp 127–128 °C; C, H, N, S analysis for C10H9NO4S.

5-Mercuriothiophene-2-acetate (60a; R4 = COO−). Mercuration Reaction

Thiophene-2-acetic acid (0.39 g, 2.8 mmol) was dissolved in 8 mL of methanol. Mercuric acetate was added with stirring, and a white precipitate appeared shortly thereafter. After 1 h, 4 mL of ether was added and the solid was collected by filtration; yield (of 60a) 0.88 g (93%). Mass spectrum (CI, NH3) shows a peak at 360 z/e corresponding to M + 1 + NH3.

The thiophene–xanthine derivative 46 was prepared as reported previously.10b Upon mercuration in dimethylformamide by a similar method, a solid product, compound 47, was obtained and characterized by californium plasma desorption mass spectroscopy.

2-[(N-Succinoylamino)methyl]-5-mercuriothiophene [60b; R4 = NHCO(CH2)2COO−]

Compound 63a (60.5 mg, 0.28 mmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of methanol and treated with 100 mg (0.31mmol) of mercuric acetate. First a solution formed, followed by crystallization of product. After 1 h, ether was added, and the precipitate was collected: yield 98 mg (84%); mp 230 °C dec.

This compound was converted to the corresponding 5-iodo derivative upon treatment at room temperature with iodine or iodine monochloride. 1H NMR of 2-[(N-succinoylamino)-methyl]-5-mercuriothiophene (61b): 8.46 (1 H, t, NH), 7.13 (1 H, d, Ar-4), 6.68 (1 H, d, Ar-3), 4.37 (2 H, d, CH2N), 2.43 (2 H, CH2), 2.35 (2 H, CH2).

5-Iodothiophene-2-acetic Acid (61a; R4 = COOH)

Compound 60a (75 mg, 0.22 mmol) was suspended in 5 mL of dimethylformamide containing 5% DMSO. Iodine crystals (77 mg, 0.31 mmol) were added with stirring. A solution formed within 1 min. Hydrochloric acid (1 M) was added, and the mixture was extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were dried (Na2SO4) and evaporated. The product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel. Rf of product (silica, ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) was 0.79.

The identical product was obtained as follows: N-Iodo-succinimide (236.2 mg, 1.05 mmol) was added to a stirred suspension of compound 59a (326.2 mg, 0.95 mmol) in methanol (30 mL). After 16 h the suspension was filtered and the methanol removed in vacuo. The remaining oil was redissolved in ethyl acetate and washed with 0.5 N HCl, and the product was extracted into a 0.5 N NaOH solution. The basic fraction was washed with CH2Cl2, acidified to pH 1.0 with 1 N HCl, and extracted with EtOAc. The product was chromatographed on a silica gel column (eluent, 17/2/1 CHCl3/MeOH/AcOH), and the solvents were removed from the product fractions in vacuo. Acetic acid was removed by azeotropic distillation with petroleum ether. The light yellow oil was redissolved in ethyl acetate, and ether was added, forming a precipitate which was removed by filtration. Evaporation of the solvent gave compound 61a as a waxy yellow solid (110 mg, 43%).

Peptide Derivatives of Thiophene-2-acetic Acid

Compound 58 reacted with L-tyrosylglycine (274 mg, 1.15 mmol) in dimethylformamide to give N-(thiophene-2-acetyl)-L-tyrosylglycine (230 mg, 55% yield). Upon mercuration in dimethylformamide as for compound 60a, N-(5-mercuriothiophene-2-acetyl)-L-tyrosylglycine (40% yield) was obtained.

2-[(N-Succinoylamino)methyl]thiophene [63a; R = (CH2)2COOH]

Thiophene-2-methanamine (Aldrich, 2.37 g, 21 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of tetrahydrofuran and treated with a solution of succinic anhydride (2.1 g, 21 mmol) in 20 mL of dimethylformamide. After ½ h, ethyl acetate (50 mL) was added, and the mixture was extracted with citric acid (1 M) three times and with water. The organic layer was dried (MgSO4). Solvent was removed and petroleum ether was added, causing white crystals of 62a to precipitate: Yield 9.4%; mp 130 °C. The NMR and mass spectra were consistent with the assigned structure. UV spectrum λmax 233 nm (log ε 4.019).

Biochemical Assays

Stock solutions of xanthines were prepared in the millimolar concentration range in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored frozen. Solutions were warmed to 50 °C prior to dilution in aqueous medium. Inhibition of binding of 1 nM [3H]-N6-(phenylisopropyl)adenosine to A1-adenosine receptors in rat cerebral cortical membranes was assayed as described.17 Inhibition of binding by a range of concentrations of xanthines was assessed in triplicate in at least three separate experiments. IC50 values, computer generated by using a nonlinear regression formula on the Graphpad program, were converted to Ki values by using a KD value for [3H]PIA of 1.0 nM and the Cheng–Prusoff equation.19

Inhibition of binding of [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine to A2-adenosine receptors in rat striatal membranes was measured as described,18 except that 5 mM theophylline was used to define nonspecific binding. N6-Cyclopentyladenosine was present at 50 nM to inhibit binding of the ligand at A1-adenosine receptors. Inhibition of binding by a range of concentrations of xanthines was assessed in triplicate in at least three separate experiments. IC50 values were converted to Ki values by the method of Bruns et al.,18 using a conversion factor derived from the affinity of [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine at A2 receptors and the Cheng–Prusoff equation.19

Acknowledgments

This project has been supported in part by National Institutes of Health SBIR Grant 1 R34 AM 37728-01 to Research Biochemicals, Inc.

References

- 1.Fredholm BB, Jacobson K, Jonzon B, Kirk K, Li Y, Daly J. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1987;9:396. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198704000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collis MG, Baxter GS, Keddie JR. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1986;38:850. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1986.tb04510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Londos C, Wolff J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruns RF, Daly JW, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.7.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruns RF, Fergus JH, Badger EW, Bristol JA, Santay LA, Hays SJ. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1987;335:64. doi: 10.1007/BF00165038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shamim MT, Ukena D, Padgett WL, Hong O, Daly JW. J Med Chem. 1988;31:613. doi: 10.1021/jm00398a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Jacobson KA, Kirk KL, Padgett WL, Daly JW. J Med Chem. 1985;28:1334. doi: 10.1021/jm00147a038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jacobson KA, Ukena D, Kirk KL, Daly JW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jacobson KA, Kirk KL, Padgett W, Daly JW. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu PH, Phillis JW, Nye MJ. Life Sci. 1982;31:2857. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Fassina G, Gaion RM, Caparrotta L, Carpenedo F. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1985;330:222. doi: 10.1007/BF00572437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ragazzi E, Froldi G, Santi Soncin E, Fassina G. Pharmacol Res Commun. 1988;20:621. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6989(88)80095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Jacobson KA, Barone S, Kammula U, Stiles G. J Chem. 1989;32:1043. doi: 10.1021/jm00125a019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jacobson KA, de la Cruz R, Schulick R, Kiriasis L, Padgett W, Pfleiderer W, Kirk KL, Neumeyer JL, Daly JW. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:3653. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90398-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jacobson KA, Ukena D, Padgett W, Daly JW, Kirk KL. J Med Chem. 1987;30:211. doi: 10.1021/jm00384a037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietz AJ, Burgison RM. J Med Chem. 1966;9:500. doi: 10.1021/jm00322a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;32:184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linden J, Patel A, Earl CQ, Craig RH, Daluge SM. J Med Chem. 1988;31:745. doi: 10.1021/jm00399a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spande T. J Org Chem. 1980;45:3081. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seevers RH, Counsell RE. Chem Rev. 1982;82:575. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khawli LA, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. Abstract ORGN80 at the 196th National Meeting of the Americal Chemical Society; Los Angeles, CA. September 25–30, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwabe U, Trost T. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1980;313:179. doi: 10.1007/BF00505731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruns RF, Lu GH, Pugsley TA. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng YC, Prusoff WH. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daly JW, Hong O, Padgett WL, Shamim MT, Jacobson KA, Ukena D. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:655. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90139-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruns RF. Biochem Pharmacol. 1981;30:325. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]