Abstract

Background

Eating food away from home and restaurant consumption have increased over the past few decades.

Purpose

To examine recent changes in calories from fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and to assess characteristics associated with consumption.

Methods

Analyses of 24-hour dietary recalls from children, adolescents, and adults using nationally representative data from the 2003–2004 through 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, including analysis by gender, ethnicity, income and location of consumption. Multivariate regression analyses of associations between demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and consumption prevalence and average daily caloric intake from fast-food and full-service restaurants.

Results

In 2007–2008, 33%, 41% and 36% of children, adolescents and adults, respectively, consumed foods and/or beverages from fast-food restaurant sources and 12%, 18% and 27% consumed from full-service restaurants. Their respective mean caloric intake from fast food was 191 kcal, 404 kcal, and 315 kcal, down by 25% (p≤0.05), 3% and 9% from 2003–2004; and among consumers, intake was 576 kcal, 988 kcal, and 877 kcal, respectively, down by 12% (p≤0.05), 2% and 7%. There were no changes in daily calories consumed from full-service restaurants. Consumption prevalence and average daily caloric intake from fast-food (adults only) and full-service restaurants (all age groups) were higher when consumed away from home versus at home. There were some demographic and socioeconomic associations with the likelihood of fast-food consumption, but characteristics were generally not associated with the extent of caloric intake among those who consumed from fast-food or from full-service restaurants.

Conclusions

In 2007–2008, fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption remained prevalent and a source of substantial energy intake.

Introduction

Away-from-home food consumption, in particular fast food, has been associated with higher total energy intake and higher intake of fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sugar, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and lower intake of micronutrients and fruits and vegetables.1–6 Also, studies have found associations between fast-food consumption and body weight.1,5,7–9 Several studies have documented increases in away-from-home consumption patterns and expenditures, particularly from fast-food sources, over the past several decades.10–15

As a percentage of total daily caloric intake, between 1977–1978 and 1994–1996, consumption of away-from-home food increased from 18% to 32% among all individuals aged ≥2 years.10 The contribution from fast food increased from 2% to 10% for children and from 4% to 12% for adults. From full-service restaurants, the share of calories increased from 1% to 4% for children and 4% to 10% for adults.

Between 1977–1978 and 1994–1996, the percentage of total daily energy from fast-food restaurants increased from 6.5% to 19% among adolescents and from 14.3% to 31.5% among young adults.11 Recent evidence for children12 showed that fast-food and full-service restaurant sources contributed 13% and 5%, respectively, of daily energy intake for children aged 2–18 years in 2003–2006, up from 10% and 4% in 1994–1998. For adults, the mean number of commercially prepared meals consumed weekly increased from 2.5 in 1987–1992 to 2.8 in 1999–2000, and the odds of eating commercially prepared food less than once a week and more than three times per week increased by 40%.13

Further, consumers spent $415 billion on away-from-home food, in 2002, up 58% from 1992.14 Evidence for adolescents from 1999 to 2004 showed that frequent (≥3 times per week) fast-food consumption increased from 19% to 27% for girls and 24% to 30% for boys.15 Evidence on more-recent changes is limited and much of the previous research focused on either away-from-home food, commercially prepared foods in general, or only on fast food. Additionally, previous studies have often focused on prevalence/frequency rather than measures of total caloric intake, particularly among consumers from such sources.

The current study aimed to document recent changes from 2003–2004 to 2007–2008 in the patterns of consumption from both fast-food and full-service restaurant sources for children, adolescents and adults. Changes over time were assessed by gender, ethnicity and SES, and in terms of location of consumption. Finally, multivariate analyses were used to examine demographic and socioeconomic characteristics associated with the prevalence of fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and daily caloric intake from these sources.

Methods

Data and Variables

Dietary recall data were drawn from the participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004, 2005–2006 and 2007–2008. NHANES is an ongoing survey based on a complex multistage sampling design nationally representative of the civilian non-institutionalized U.S. population. A complete description of the data-collection procedures and survey design are provided online.16 Changes in outcomes were reported based on changes from 2003–2004 to 2007–2008, and regression analyses were undertaken using all three NHANES survey rounds from 2003–2004, 2005–2006, and 2007–2008.

Three age groups were examined separately: children aged 2–11 years, adolescents aged 12–19 years, and adults aged 20–64 years. Changes in consumption were examined for subpopulations by gender, race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic; other racial subpopulations were not examined due to small sample sizes) and by income. Low income was defined (for individuals within families) as <130% of the federal poverty level (FPL), middle income as 130%–300% of the FPL, and high income as >300% of the FPL.

Information on consumption was based on the 24-hour dietary recall data in NHANES for which respondents reported on all food and beverages consumed in the prior 24 hours. Caloric and nutritional content of food and beverages in NHAHES was assessed according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrient database. Data from Day 1 collected by trained dietary interviewers in a mobile examination center (MEC) were used. Survey participants aged ≥12 years completed the dietary interviews on their own; proxy-assisted interviews were conducted with children aged 6–11 years; and proxy respondents reported for children aged <6 years.

Survey respondents were asked about the source of each food and beverage item obtained (e.g., a store; restaurant fast food/pizza; restaurant with waiter/waitress; bar/tavern/lounge; restaurant with no additional information; child care center; vending machine). In this study, fast-food restaurant was defined to include: restaurant fast food/pizza. Full-service restaurant was defined to include: restaurant with waiter/waitress, bar/tavern/lounge, and restaurant no additional information. Respondents were also asked whether they consumed the food and beverage item at home or away from home. From these two questions, the source and location of intake for each food or beverage item were determined based on whether it was from: (1) a fast-food restaurant (eaten away from home or at home); and (2) a full-service restaurant (eaten away from home or at home).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were undertaken using STATA 11.1, and weights were used to adjust for the NHANES complex sampling design. Given that the dietary recall data were obtained from the MEC-examined sample people, the MEC sample weights were used. For each of the fast-food and full-service restaurant sources, the prevalence of consumption, mean daily energy intake in kilocalories (kcal), and mean daily energy intake (kcal) conditional on consumption (that is, among consumers) from the given source was examined, and changes over time were tested. The contribution of fast-food and full-service consumption to daily total energy intake (TEI) also was examined.

Multivariate regressions of the prevalence of consumption were estimated using logistic regression models and ORs, and the set default 95% CIs were reported. Models of energy intake conditional on consumption were estimated using ordinary least-squares regression analysis. The multivariate regression analyses controlled for age, gender, race (white, black, Hispanic, other), marital status (married, never married, separated, divorced, widowed), the number of individuals in the household, income (low, middle, high), education (less than high school, high school, some college or vocational school, college or more), intake day (weekend/weekday), and survey wave (2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008).

Results

Recent Changes in Daily Caloric Intake from Fast-Food and Full-Service Restaurants

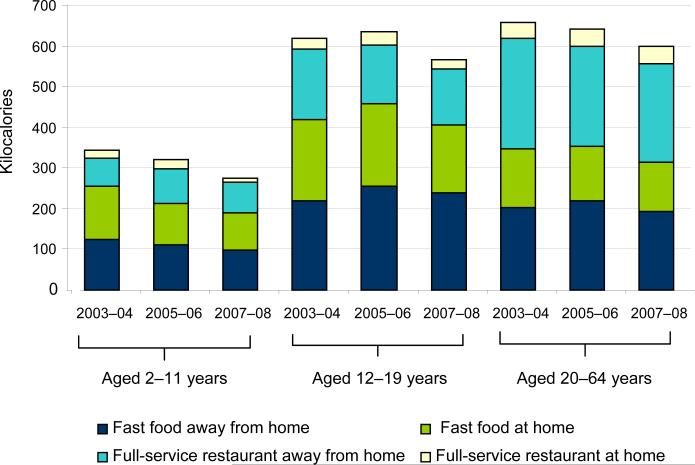

Table 1 shows that, in 2007–2008, 33% of children, 41% of adolescents and 36% of adults consumed foods and/or beverages from fast-food restaurants, and their respective mean caloric intake was 191 kcal, 404 kcal, and 315 kcal down by 25% (p≤0.05), 3%, and 9% from 2003–2004 (Figure 1). Among those who consumed fast food, daily energy intake from fast food was on average 576 kcal for children, 988 kcal for adolescents, and 877 kcal for adults, respectively in 2007–2008, down from 2003–2004 by 12% (p≤0.05), 2%, and 7%. Adolescents remained the most prevalent fast-food consumers overall and continued to have the highest daily energy intake from fast food.

Table 1.

Daily total energy intake from fast-food and full-service restaurants, by age group, location, and year

| Prevalence (%) | Mean daily energy (kcal) intake (% of total energy intake) | Mean daily energy (kcal) intake conditional on consumption (% of total energy intake) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2004 | 2007–2008 | 2003–2004 | 2007–2008 | % change over time | 2003–2004 | 2007–2008 | % change over time | |

| AGE 2–11 YEARS (n=1664, 2044) | ||||||||

| Fast food | 39 | 33 | 255 (12) | 191(10) | –25* | 652(32) | 576(31) | –12* |

| Away from home | 19 | 17 | 123 (6) | 97(5) | –21 | 638(31) | 566(29) | –11 |

| At home | 23 | 19 | 132 (6) | 94(5) | –29* | 575(28) | 502(28) | –13* |

| Full service | 15 | 12 | 89 (4) | 84(4) | –6 | 611(30) | 683(34) | 12 |

| Away from home | 9 | 11 | 69 (3) | 74(4) | 7 | 728(35) | 701(35) | –4 |

| At home | 6a | 3a | 20a(1) | 10a(1) | –49* | 342(18) | 406(20) | 19 |

| Age 12–19 years (n=2013, 1184) | ||||||||

| Fast food | 41 | 41 | 418(17) | 404(17) | –3 | 1012(41) | 988(42) | –2 |

| Away from home | 24 | 25 | 221(9) | 239(10) | 8 | 932(39) | 961(40) | 3 |

| At home | 21 | 20 | 198(8) | 165(7) | –17 | 921(37) | 815(36) | –11 |

| Full service | 19 | 18 | 201(8) | 160(7) | –20 | 1026(41) | 910(42) | –11 |

| Away from home | 16 | 15 | 173(7) | 138(6) | –20 | 1114(42) | 915(43) | –18* |

| At home | 5a | 3a | 28a(1) | 23a(1) | –18 | 608a(29) | 731(33) | 20 |

| Aged 20–64 years (n=2920, 4107) | ||||||||

| Fast food | 37 | 36 | 348(14) | 315(13) | –9 | 943(39) | 877(37) | –7 |

| Away from home | 24 | 24 | 204(8) | 195(8) | –4 | 867(36) | 812(34) | –6 |

| At home | 16a | 15a | 144a(6) | 121a(5) | –16 | 888(37) | 784(34) | –12* |

| Full service | 30 | 27 | 311(13) | 284(11) | –9 | 1028(41) | 1032(42) | 0 |

| Away from home | 26 | 23 | 270(11) | 242(10) | –10 | 1024(41) | 1048(42) | 2 |

| At home | 6a | 6a | 41a(2) | 42a(2) | 2 | 688a(28) | 695a(28) | 0 |

Significant difference between food consumed away from home versus at home at p≤0.05 level.

Sample sizes, n, shown in parentheses for 2003–2004 and 2007–2008.

Change significant at p≤0.05 level

Figure 1.

Energy intake from fast-food and full-service restaurants, by age groups, location, and year

Note: Based on NHANES 2003–2004, 2005–2006, and 2007–2008 data and sample sizes presented in Table 1.

By place of consumption, in 2007–2008, children were more likely to consume fast food at home than away from home, whereas away-from-home versus at-home consumption was more prevalent among teens. However, the differences in prevalence and daily caloric intake for fast food were not significantly different by place of consumption for either children or adolescents. However, children and adolescents had significantly lower prevalence and overall daily caloric intake from full-service restaurants consumed at home versus away from home. Among adults, consumption prevalence and intake were significantly higher for both fast-food and full-service restaurants when consumed away from home compared to at home.

Although the prevalence of full-service restaurant consumption among children and adolescents was substantially lower than fast-food restaurant use, it was nonetheless nontrivial at 12% for children and 18% for adolescents, in 2007–2008, with average daily intake among consumers of 683 kcal for children and 910 kcal for teens. Among adults, approximately one quarter (27%) consumed from full-service restaurants daily in 2007–2008, obtaining, on average, 1032 kcal. There were no significant changes in full-service restaurant use or intake overall across age groups, but there were some reductions for children and adolescents for consumption at home.

In relative terms, based on contributions to daily TEI, 10%, 17% and 13%, on average, came from fast-food restaurants, in 2007–2008, among children, adolescents and adults, respectively, and among those who were consumers, fast-food intake accounted for 31%, 42% and 37% of TEI. This contribution remained fairly flat across all age groups except for a change in contribution to TEI among children from 12% in 2003–2004 to 10% in 2007–2008. The percentage of TEI from full-service restaurants remained fairly stable for children and teens at 4% and about 7%, whereas among adults, TEI from full-service restaurants decreased from 13% in 2003–2004 to 11% in 2007–2008.

Appendixes A and B (available online at www.ajpmonline.org) show that for children aged 6–11 years and male children there were significant reductions in overall caloric intake (–27%) from fast food and intake conditional on fast-food consumption was significantly lower for males (–14%) between 2003–2004 and 2007–2008. White children had a 29% reduction in caloric intake from fast-food restaurants overall and a 15% reduction among consumers. No significant changes were found by subpopulations of children for intake from full-service restaurants. For adolescents and adults, there were no changes identified in fast-food caloric intake for any of the subpopulations. However, among those who ate at full-service restaurants, intake was significantly lower between 2003–2004 and 2007–2008 among female (–19%) and low-income (–25%) adolescents and overall caloric intake from full-service restaurants was 19% lower among adult women.

Multivariate Associations with Prevalence and Intake

Appendixes C and D (available online at www.ajpmonline.org) show that men were more likely to consume from restaurants and both adolescent boys and men had higher daily caloric intake from these sources than girls/women. The likelihood of restaurant consumption did not differ between younger (aged 2–5 years) and older (aged 6–11 years) children, but among consumers caloric intake was higher among older children from both fast-food (+236 kcal) and full-service (+264 kcal) restaurants. Older adolescents (aged 14–19 years) had a higher prevalence of consumption from fast-food (+65%) and full-service (+48%) restaurants and consumed an additional 146 kcal and 222 kcal from these respective restaurant sources compared to those aged 12–13 years.

Young versus middle-aged adults were significantly more likely to consume from fast-food restaurants and had higher caloric intake (+123 kcal). Older versus middle-aged adults were less likely to consume from fast-food or full-service restaurants and reported significantly lower daily caloric intake. Living in larger households was associated with lower prevalence of consumption from full-service restaurants (adolescents and adults) and higher prevalence of fast-food consumption (adults only).

There were no ethnic associations with fast-food consumption among children. Black adolescents (+29%) and adults (+49%) were more likely to consume fast food compared to their white counterparts, although ethnicity was not associated with the magnitude of daily caloric intake. Across all age groups, blacks compared to whites were consistently less likely to consume food from full-service restaurants: 47%, 60% and 36% lower likelihood among children, adolescents and adults, respectively, and daily caloric intake was lower for black adolescents.

Among children aged 2–11 years, having parents with a college education versus those with less than a high school education was associated with a 36% lower likelihood of fast-food consumption, whereas having more-highly educated parents was associated with higher likelihood of consumption from full-service restaurants. Children from high- versus low-income families were 59% more likely to consume fast food and almost twice as likely to consume from full-service restaurants. There were no socioeconomic associations with adolescents’ fast-food consumption, although full-service restaurant consumption prevalence was higher for adolescents from higher-educated and higher-income families. Compared to those who had not completed high school, high school–educated adults were 24% more likely to consume fast food. Middle-and higher-income adults were more likely to consume from restaurants; although, among those who consumed, high-income adults consumed 71 fewer calories per day from fast food compared to their low-income counterparts.

The results from additional controls show that children were 70% more likely to consume from a full-service restaurant and report higher caloric intake on the weekend days versus weekdays. Adolescents were 31% more likely to consume from both fast-food and full-service restaurants on a weekend versus weekday with intake higher from full-service restaurants. Adults, on the other hand, were less likely to consume fast food on the weekend, suggesting that fast-food consumption patterns may be associated with preferences for quick service during the work week. Fast-food caloric intake among children was estimated to be 62 kcal per day lower in 2007–2008 versus 2003–2004; no other associations over time from 2003–2004 to 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 were found.

Discussion

This study used data from NHANES 2003–2004 through 2007–2008 to examine changes in fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and associations with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Results showed that among children there was a recent 25% reduction in the total average daily caloric intake from fast-food restaurants and a 12% reduction in average daily caloric intake with reductions for older (aged 6–11 years), male, and white children. There were no recent changes in fast-food intake for adolescents or adults in general, nor among any of the subpopulations based on age, income, or race/ethnicity.

Overall, for children, adolescents and adults there were no changes between 2003–2004 and 2007–2008 in the average daily calories consumed from full-service restaurants, although there were reductions for female and low-income adolescents and for women. Adolescents remained the most prevalent fast-food consumers and had the highest energy intake from fast food. On average, prevalence of consumption and caloric intake from full-service (all age groups) and fast-food (adults only) restaurants was greater when consumed away from home compared to at home.

In 2007–2008, one third of children aged 2–11 years consumed fast food daily, and while down from 39% in 2003–2004, this figure remains higher than the prevalence reported from the mid-1990's of 25% for children aged 4–8 years and 26% for those aged 9–13 years.4 Among adolescents, prevalence was slightly higher at 41% in 2003–2004 through 2007–2008 compared to data for youth aged 14–19 years reported to be 39% in the mid-1990s.4 Overall, in 2007–2008, TEI from fast-food and full-service restaurants, respectively, was 10% and 4% for children aged 2–11 years and 7% and 17% for adolescents aged 12–19 years.

Previous research showed that as a percentage of TEI, the contribution from fast-food and full-service restaurants, respectively, increased from 2% to 10% and 1% to 4% from 1977–1978 to 1994–1996 for children aged 2–17 years. More-recent evidence showed a further increase in TEI from fast-food sources for children aged 7–12 years, from 9% in 1994–1998 to 11% in 2003–2006.12 In comparison, the study results in this paper show a recent decrease among children in the contribution of fast food to TEI from 12% in 2003–2004 to 10% in 2007–2008.

For adolescents, over the study period, fast-food consumption remained persistently prevalent (41%) and contributed 17% of TEI, on average, overall and 42% of TEI, on average, on days when fast food was consumed by adolescents. In 2007–2008, 36% and 27% of adults consumed from fast-food and full-service restaurants daily with no recent changes in intake since 2003–2004. The contribution to TEI from these sources was generally unchanged compared to the data from 1994–1996.10

The multivariate regression analyses showed that the likelihood of consuming from fast-food restaurants was greater for black and high school–aged adolescents but was not associated with SES. Black adults also were more likely than their white counterparts to consume fast food. Higher-income children and adults were more likely to consume from fast-food restaurants but children with more-highly educated adults in the household were less likely to do so. The likelihood of full-service restaurant consumption but not the extent of caloric intake was consistently associated with higher SES among all age groups. Further, blacks across all age groups were consistently less likely to consume from full-service restaurants. However, among consumers, sociodemographic and economic characteristics were generally not associated with the extent of calories consumed from restaurant sources.

This study was subject to some limitations. First, the 24-hour dietary recall data were obtained via self-report and are subject to error – such data have been shown to be subject to under-reporting17,18 and therefore, the estimates of average daily caloric intake may be considered as lower bounds. Second, a single 24-hour dietary recall may not precisely capture longer-term consumption patterns.19 Third, the measurement of restaurant types may have been subject to classification error. Fourth, the multivariate regression analyses are limited by the cross-sectional design of the NHANES data which does not permit assessment of causal relationships. Finally, the 2009–2010, the 24-hour dietary recall data from NHANES were not available at the time of this study, and future research should continue to monitor changes in fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption.

The per capita availability of limited-service and full-service restaurants increased by 12.3% and 7.4%, respectively, between 2002 and 2007.20,21 In 2007, sales at limited-service restaurants reached $183 billion and were $192 billion for full-service restaurants; both up by roughly one third from 2002.20 The inflation-adjusted cost of consuming from either limited-service or full-service restaurants was shown to be relatively constant over the 2000s (22). In addition, fast-food advertising exposure increased substantially between 2003 and 2009, particularly among teens, and is the most prevalent category of foods ads on TV seen by both children and teens23,24 and research documents the poor nutritional content of fast foods advertised to children.25

The availability of fast-food restaurants is found to be greater in lower-income and minority neighborhoods26 and such restaurants are also shown to cluster around schools, particularly high schools.27,28 The ubiquitous presence and promotion of restaurants in the U.S. highlights the importance of understanding patterns of consumption and implications for dietary intake. Continued monitoring of consumption patterns is important to assess whether the recent reductions among children and the leveling off among adolescents and adults reflect a potential reversal from previous trends in restaurant consumption or whether they may be only a temporary change reflective of the recent recession.29 Overall, the multivariate results from this study suggest that populations from all socioeconomic and demographic groups would benefit from policies aimed at improving dietary choices to reduce caloric intake when consuming food and beverages from fast-food and full-service restaurants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant number R01CA138456 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and grant number 11IPA1102973 from the CDC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI, the NIH, or the CDC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.French SA, Harnack L, Jeffery RW. Fast food restaurant use among women in the Pound of Prevention study: dietary, behavioral and demographic correlates. Int J Obes. 2000;24(10):1353–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25(12):1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paeratakul S, Ferdinand DP, Champagne CM, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Fast-food consumption among U.S. adults and children: dietary and nutrient intake profile. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(10):1332–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)01086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):112–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman SA, Vinyard BT. Fast food consumption of U.S. adults: impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(2):163–168. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebastian RS, Wilkinson Enns C, Goldman JD. U.S. Adolescents and MyPyramid: Associations between Fast-Food Consumption and Lower Likelihood of Meeting Recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2):226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binkley JK, Eales J, Jekanowski M. The relation between dietary change and rising U.S. obesity. Int J Obes. 2000;24(8):1032–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(6):842–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulkerson JA, Farbakhsh K, Lytle L, et al. Away-from-home family dinner sources and associations with weight status, body composition, and related biomarkers of chronic disease among adolescents and their parents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(12):1892–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: Changes and consequences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34(3):140–50. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in U.S. between 1977 and 1996: Similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):370–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poti JM, Popkin BM. Trends in Energy Intake among U.S. Children by Eating Location and Food Source, 1977–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Eating out in America, 1987–2000: trends and nutritional correlates. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart H, Blisard N, Bhuyan S, Nayga RM., Jr . The demand for food away from home: Full service or fast food? Food and Rural Economics Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.; 2004. Agricultural Economic Report Series. Report 829. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer KW, Larson NI, Nelson MC, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Fast food intake among adolescents: Secular and longitudinal trends from 1999 to 2004. Prev Med. 2009;48(3):284–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. DHHS, CDC; Hyattsville MD: 2011. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertz W, Tsui JC, Judd JT, et al. What are people really eating? The relation between energy intake derived from estimated diet records and intake determined to maintain body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(2):291–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briefel RR, Sempos CT, McDowell MA, Chien S, Alaimo K. Dietary methods research in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: underreporting of energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4):1203S–9S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1203S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among U.S. children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1604–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Census Bureau Accommodation and Food Services: Geographic Area Series: Comparative Statistics for the U.S. (2002 NAICS Basis): 2007 and 2002. 2007 factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ECN_2007_US_72A2&prodType=table.

- 21.U.S. Census Bureau National Intercensal Estimates (2000–2010) 2011 www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal/national/nat2010.html .

- 22.U.S Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index; All Urban Consumers. www.bls.gov/data/. 2012.

- 23.Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Trends in exposure to television food advertisements among children and adolescents in the U.S. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(9):794–802. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Trends in the nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children in the U.S.: analyses by age, food categories, and companies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(12):1078–86. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Fast food F.A.C.T.S.: Evaluating fast food nutrition and marketing to youth. Yale University, Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood Environments: Disparities in Access to Healthy Foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin SB, Melly SJ, Sanchez BN, Patel A, Buka S, Gortmaker SL. Clustering of fast-food restaurants around schools: A novel application of spatial statistics to the study of food environments. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1575–1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zenk SN, Powell LM. U.S. secondary schools and food outlets. Health Place. 2008;14(2):336–46. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumcu A, Kaufman P. Food spending adjustments during recessionary times. 3. Vol. 9. Amber Waves, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.