Abstract

Understanding how biogeochemical cycles relate to the structure of ecological communities is a central research question in ecology. Here we approach this problem by focusing on body size, which is an easily measured species trait that has a pervasive influence on multiple aspects of community structure and ecosystem functioning. We test the predictions of a model derived from metabolic theory using data on ecosystem metabolism and community size structure. These data were collected as part of an aquatic mesocosm experiment that was designed to simulate future environmental warming. Our analyses demonstrate significant linkages between community size structure and ecosystem functioning, and the effects of warming on these links. Specifically, we show that carbon fluxes were significantly influenced by seasonal variation in temperature, and yielded activation energies remarkably similar to those predicted based on the temperature dependencies of individual-level photosynthesis and respiration. We also show that community size structure significantly influenced fluxes of ecosystem respiration and gross primary production, particularly at the annual time-scale. Assessing size structure and the factors that control it, both empirically and theoretically, therefore promises to aid in understanding links between individual organisms and biogeochemical cycles, and in predicting the responses of key ecosystem functions to future environmental change.

Keywords: climate change, allometry, size structure, ecosystem functioning, metabolic theory, global warming

1. Introduction

Since its inception by Arthur Tansley in 1935, the concept of the ecosystem has been applied in many ways [1–6]. Still, the fundamental tenet that organisms and their physical, biological and chemical environment are intimately linked has remained the cornerstone of ecology for almost a century. Ecosystems are frequently studied from either the ‘community’ or ‘ecosystem’ perspectives. The community perspective (advanced by Charles Elton [7] and Robert MacArthur [8–10]) emphasizes the importance of organisms, their population-level interactions and their community-level structure on ecosystem dynamics. By contrast, the ecosystem perspective (pioneered by Raymond Lindeman [6] and Eugene Odum [2]) emphasizes the overarching constraints imposed by the physical laws of thermodynamics and chemical stoichiometry on ecosystem processes, including primary production, carbon sequestration and nutrient cycling.

In reality, community structure and ecosystem functioning are inextricably linked, but our understanding of these linkages and how they arise is, in general, quite limited. For example, while it seems obvious that the abundances of heterotrophic populations in a food web should increase with autotrophic net primary production, predicting the partitioning of energy and matter within- and among-species populations or body-size classes remains challenging. This is because food-web structure is a consequence of a complex network of biotic interactions among individuals comprising the community [11], as well as abiotic constraints on these interactions [12].

Understanding how community structure and ecosystem functioning are related has taken on increased urgency in the light of forecasted global warming [13–15] and the unprecedented rates of biodiversity loss related to the human domination of the Earth's biosphere [8–10,16]. Relationships between aspects of community structure (e.g. biodiversity) and ecosystem functioning (e.g. CO2 sequestration, decomposition, primary production and nutrient cycling) have been identified in particular systems [17–19], but these relationships have often lacked generality owing to the idiosyncratic responses of biota [19,20] which, in part, reflect trait differences among species [11,21].

Here we approach this problem by focusing on how environmental warming affects three key ecosystem processes—ecosystem respiration, gross primary production and carbon sequestration—through its effects on the size- and temperature-dependencies of respiration and photosynthesis at the individual level, and body-size structure at the community level [12,22,23]. We do so by testing the predictions of a model derived from metabolic theory [24–27]. Metabolic theory is particularly useful for understanding how physiology, community structure and abiotic variables combine to influence ecosystem metabolism, because it relates complex ecosystem-level phenomena to the effects of body mass and temperature on individual-level metabolic rate [16,24,25]. We evaluate the predictions of the model by combining, for the first time, previously published data on plankton community size structure [17–19,28] and ecosystem metabolism [29] that were collected as part of an aquatic mesocosm experiment, designed to assess the effects of a 4°C rise in ambient temperature. Previous work from this experiment has demonstrated that warming resulted in a reduction in carbon sequestration capacity [29] and a shift in community size structure [28]. Here we combine these datasets in an attempt to synthesize the ‘community’ and ‘ecosystem’ perspectives.

2. Overview of the experimental data

The experiment comprised 20 outdoor freshwater mesocosms (approx. 1 m3, 0.5 m water depth), which were seeded with organisms from surrounding natural aquatic environments in December 2005 and were then left to natural colonization until April 2007, when sampling began [28,29]. Ten of the 20 mesocosms were subjected to experimental warming starting in September 2006. These mesocosms were warmed by 3–5°C (mean 4°C) above ambient temperature to simulate the level of warming expected for temperate latitudes by the end of the century under the IPCC A1B scenario.

To evaluate the predictions of our models, we used daily measurements of ecosystem respiration and gross primary production from Yvon-Durocher et al. [29] and estimates of community size structure from Yvon-Durocher et al. [28]. Ecosystem-level metabolic fluxes over a 24 h diel cycle (gross primary production (P) and ecosystem respiration (R)) were estimated for each replicate of each treatment on alternate months over the course of 1 year (April 2007–April 2008). These fluxes were estimated by assuming that changes in dissolved oxygen concentration over a diel cycle in aquatic ecosystems largely reflect the balance between the photosynthetic and respiratory metabolism [30]. Dissolved oxygen concentrations were measured using YSI 600XLM multiparameter Sondes equipped with 6562 rapid pulse dissolved oxygen sensors. Sensors were deployed for 24 h in a heated- and unheated-treatment pair of mesocosms on each of the seven sampling occasions over the year. Measurements of dissolved oxygen, temperature and pH were taken every 15 min for 24 h at mid depth (0.25 m) in the water column of each mesocosm. Changes in dissolved oxygen concentration during the daytime, ΔOdt, and night-time, ΔOnt, were then calculated by subtracting the O2 concentration at the end of each 15-minute time interval from the concentration at the beginning of the interval. Finally, total ecosystem fluxes over a 24 h period were calculated as follows: P = ∑ΔOdt + Rdt, where Rdt and ∑ΔOdt are, respectively, the total respiratory flux and the net ecosystem productivity during the daytime; and R = Rdt + Rnt, where Rnt is total respiratory flux during the night-time (=∑ΔOnt). The parameter Rdt was estimated by extrapolating the mean rate of night-time respiration across the hours of daylight.

Annual estimates of ecosystem respiration, τ〈R〉τ, and gross primary production, τ〈P〉τ, were estimating by linearly interpolating between sampling occasions to generate 365 estimates of flux over a time period of length τ = 365 days, taking averages of these estimates, 〈R〉τ and 〈P〉τ, and then multiplying these daily averages by τ. In this study, data from one warmed pond (no. 17) and one ambient pond (no. 3) were excluded because they were deemed to be outliers based on preliminary analyses of flux–community relationships.

Size structure of the plankton community in each mesocosm was measured once at the beginning (April) and the end (October) of the growing season. Data from the two samples were pooled for each mesocosm for all of the analyses presented here. Estimating size structure entailed first collecting a 2 l sample from the water column. Organisms in this sample were then subdivided into two size categories using a 80 μm sieve. All organisms greater than 80 µm (typically zooplankton) were preserved in 4 per cent formalin, and then counted and measured using a Nikon SMZ1500 dissection microscope. For organisms less than 80 µm (typically phytoplankton), a 100 ml subsample of the 2 l volume was preserved in 1 per cent Lugol's iodine; 400 individuals were then counted and measured using an inverted microscope (Leica DMIRE2) after settling for a period of 24 h in a 10 ml Utermöhl sedimentation chamber. The size of each organism, in units of carbon mass, was estimated based on its biovolume, which was calculated using length and width measurements after assigning the organism to an appropriate geometric shape. Measurements of length and width were obtained using the Openlab interactive image analysis system after digitally capturing the microscope images using a Hamamatsu C4742-95 camera. Biovolumes were converted to carbon units using a multiplication factor of 0.109 μg C μm−3 (= 1.09 μg wet mass μm−3 × 0.25 μg dry mass μg−1 wet mass × 0.4 μg C μg−1 dry mass). A more detailed description of the techniques used to estimate community size structure and ecosystem metabolism can be found in Yvon-Durocher et al. [28,29], respectively.

3. Reconciling ecosystem metabolism with community size structure through time

The overall rates of respiratory and photosynthetic metabolism in an ecosystem are governed by the sizes, abundances and metabolic rates of the organisms comprising that ecosystem [24,25,31]. This notion implies fundamental linkages between community size structure and biogeochemical fluxes at the ecosystem level. We now present and test a number of predictions that arise from a model [24] derived from metabolic theory [26], which yields predictions on these linkages and their relationship to temperature change.

(a). Quantifying the short-term size and temperature dependence of ecosystem metabolism

Metabolic theory provides quantitative predictions for the size- and temperature-dependence of individual metabolic rates (photosynthetic or respiratory flux), and the relationship of these rates to ecosystem-level flux (P or R) [24–26]. The combined effects of individual mass, mi, and temperature, T (in degrees Kelvin), on metabolic rate are predicted using the equation

| 3.1 |

where bo is an individual-level normalization for metabolic rate, which differs between photosynthesis and respiration. The mass dependence of metabolic rate,  reflects mass-dependent changes in the densities of metabolic organelles (i.e. chloroplasts, respiratory complexes) [24] and is characterized by an exponent α that takes a canonical value close to three-fourths for metazoans [32], but may be closer to unity for unicellular prokaryotes and eukaryotes [33]. The temperature dependence, characterized by the Boltzmann factor, e−E/kT, reflects the exponential effects of temperature, T, on the kinetics of biochemical reactions in metabolic organelles, where k is the Boltzmann constant (8.62 × 10−5 eV K−1) and E is an activation energy (1 eV = 96.49 kJ mol−1) used to characterize the temperature sensitivity.

reflects mass-dependent changes in the densities of metabolic organelles (i.e. chloroplasts, respiratory complexes) [24] and is characterized by an exponent α that takes a canonical value close to three-fourths for metazoans [32], but may be closer to unity for unicellular prokaryotes and eukaryotes [33]. The temperature dependence, characterized by the Boltzmann factor, e−E/kT, reflects the exponential effects of temperature, T, on the kinetics of biochemical reactions in metabolic organelles, where k is the Boltzmann constant (8.62 × 10−5 eV K−1) and E is an activation energy (1 eV = 96.49 kJ mol−1) used to characterize the temperature sensitivity.

Metabolic theory predicts, and empirical data show, that the overall temperature sensitivities of respiration and photosynthesis differ [24,29,34–36]. The activation energy of respiration, ER, tends to fall within a relatively narrow range (0.6–0.7 eV) [37] that reflects the average activation energies of metabolic reactions in the respiratory complex [38]. The temperature sensitivity of aquatic photosynthesis can be approximated using an ‘effective’ activation energy, EP ≈ 0.32 eV, that is about half that of respiration [24]. At the individual level, these differential activation energies imply that respiratory fluxes should increase at a faster rate with temperature (approx. 16-fold from 0–30°C) than photosynthetic fluxes (approx. fourfold from 0 to 30°C). These different temperature dependencies have been shown to have important implications for the effects of warming on carbon sequestration in ecosystems [29].

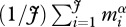

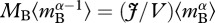

Owing to mass and energy balance, the rate of ecosystem respiration per unit volume, RB(T), by a biomass pool, B, is equal to the sum of the individual respiratory fluxes,  characterized by equation (3.1), for all J individuals contained in a volume V,

characterized by equation (3.1), for all J individuals contained in a volume V,

|

3.2 |

where  is the individual-level normalization for respiration, which is generally lower for autotrophs than heterotrophs [38]. In this expression, MB is total biomass per unit volume,

is the individual-level normalization for respiration, which is generally lower for autotrophs than heterotrophs [38]. In this expression, MB is total biomass per unit volume,  is an average for body size (=

is an average for body size (= ) that accounts for size-dependent changes in metabolic rate, characterized by α, and

) that accounts for size-dependent changes in metabolic rate, characterized by α, and  is an average for

is an average for  which is weighted by biomass rather than individual abundance, such that

which is weighted by biomass rather than individual abundance, such that  is mass-corrected biomass in equation (3.2). Mass correction of biomass, by

is mass-corrected biomass in equation (3.2). Mass correction of biomass, by  is necessary to account for changes in the density of metabolic organelles with body mass [39]. Mass-corrected biomass is predicted to be proportional to the total number of metabolic organelles in the biomass pool, which is determined in part by the total biomass, and in part by the relative numbers of small versus large organisms. Thus, mass-corrected biomass can be viewed as a measure of the total ‘metabolic capacity’ of the biomass pool in the ecosystem.

is necessary to account for changes in the density of metabolic organelles with body mass [39]. Mass-corrected biomass is predicted to be proportional to the total number of metabolic organelles in the biomass pool, which is determined in part by the total biomass, and in part by the relative numbers of small versus large organisms. Thus, mass-corrected biomass can be viewed as a measure of the total ‘metabolic capacity’ of the biomass pool in the ecosystem.

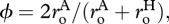

Separately performing the summation in equation (3.2) for autotrophs and heterotrophs yields expressions that relate daily respiratory fluxes of the two biomass pools, RA(T) and RH(T), to individual-level normalizations for respiration,  and

and  , standing stocks of community biomass, MA and MH, biomass-weighted averages for individual body mass,

, standing stocks of community biomass, MA and MH, biomass-weighted averages for individual body mass,  and

and  and the mass-dependencies of individual respiration, characterized by α:

and the mass-dependencies of individual respiration, characterized by α:

| 3.3a |

and

| 3.3b |

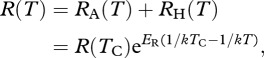

Ecosystem respiration, R(T), is equal to the sum of these fluxes

|

3.4a |

where

|

3.4b |

is the average of the two respiratory normalizations

is the average of the two respiratory normalizations  and

and  The final expression of equation (3.4b) includes a dimensionless parameter

The final expression of equation (3.4b) includes a dimensionless parameter  which facilitates direct comparisons of mass-corrected expressions for autotroph biomass,

which facilitates direct comparisons of mass-corrected expressions for autotroph biomass,  and total biomass,

and total biomass,  , using common units. In equation (3.4a), the temperature data are centred using a fixed, arbitrary value, TC (=288 K = 15°C) so that R(TC) is equal to the ecosystem respiration rate at 15°C [27]. As demonstrated by equation (3.4b), the model predicts that R(TC) is governed by the mass-corrected biomass terms for autotrophs,

, using common units. In equation (3.4a), the temperature data are centred using a fixed, arbitrary value, TC (=288 K = 15°C) so that R(TC) is equal to the ecosystem respiration rate at 15°C [27]. As demonstrated by equation (3.4b), the model predicts that R(TC) is governed by the mass-corrected biomass terms for autotrophs,  and heterotrophs,

and heterotrophs,  and the normalization constants for the two groups,

and the normalization constants for the two groups,  and

and  which together govern the total ‘respiratory capacity’ of the ecosystem.

which together govern the total ‘respiratory capacity’ of the ecosystem.

Similarly, the rate of gross primary production (i.e. the gross fixation of CO2 by photosynthesis in the ecosystem) is obtained by summing the individual-level photosynthetic rates,  for all the autotrophs in the ecosystem (following equations (3.1) and (3.2)),

for all the autotrophs in the ecosystem (following equations (3.1) and (3.2)),

|

3.5 |

where

| 3.6 |

is the rate of gross primary production at 15°C, and po is an individual-level normalization for photosynthesis. Thus, P(TC) quantifies the ecosystem's ‘photosynthetic capacity’ that in turn is predicted to be directly proportional to the mass-corrected biomass of the autotroph community,

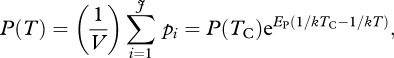

Equations (3.3)–(3.6) yield three predictions. The first prediction is that, after controlling for mass-corrected biomass, short-term gross primary production (i.e. gross photosynthetic flux, equation 3.5) and ecosystem respiration (equation 3.4a) should exhibit different temperature dependencies governed by the activation energies of photosynthesis (approx. 0.32 eV) and respiration (approx. 0.65 eV), respectively. To test this prediction, we fit a constrained model using a Bayesian modelling framework to simultaneously estimate the temperature dependencies of photosynthesis, Ep, and respiration, ER, as well as the scaling exponent, α, required to calculate mass-corrected biomass for each mesocosm (see §5). Consistent with this prediction, the observed temperature dependence of short-term gross primary production (figure 1 and table 1) was weaker than that of ecosystem respiration (figure 1 and table 1), as documented previously in Yvon-Durocher et al. [29] for these mesocosms. These findings are consistent with field studies conducted in terrestrial [24,27,36], marine [34,35] and freshwater ecosystems [27,40,41].

Figure 1.

The short-term temperature dependencies of (a) daily gross primary production and (b) daily ecosystem respiration for heated (filled circles) and ambient treatments (open circles) over the annual temperature cycle. Each data point corresponds to a measurement in a single mesocosm on one of the seven sampling occasions. The solid lines correspond to the predictions of the constrained model, which was fitted to data using equations (3.3)–(3.6) and yielded the parameter estimates listed in table 1. Fluxes were standardized using these estimates in combination with community size-structure data for each pond. The dashed lines are unconstrained OLS regression models fitted to bivariate relationships (parameter estimates and statistics listed in the figure panels). Both regression models yielded 95% CIs for the slopes that overlapped with those of the constrained model (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Results of constrained model fitting, which entailed estimating the parameters below simultaneously by fitting equations (3.3)–(3.6) to the following datasets: daily respiration, daily gross primary production, temperature and community size structure (see §5). The constrained models were estimated using Bayesian model fitting.

| parameter | units | estimate | 95% credible interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP | eV | 0.381 | 0.291–0.488 |

| ER | eV | 0.588 | 0.507–0.680 |

| α | n.a. | 0.426 | 0.385–0.464 |

|

g1−α d−1 | −12.795 | −13.895 to −11.799 |

|

g1−α d−1 | −13.202 | −14.296 to −12.156 |

|

g1−α d−1 | −7.199 | −8.798 to −6.413 |

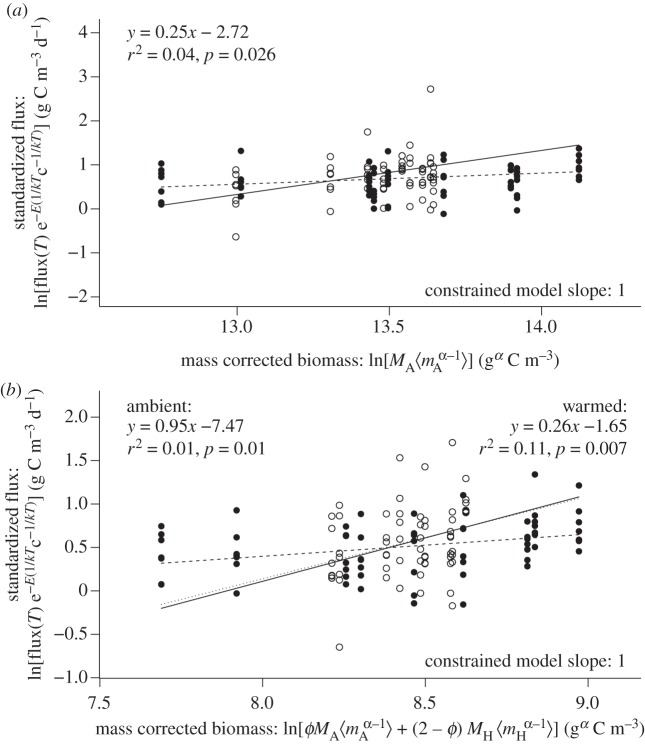

The second prediction is that, after controlling for temperature, T, gross primary production, P, and ecosystem respiration, R, should increase proportionally with the mass-corrected biomass for autotrophs and the entire community, respectively. To test this prediction, we calculated temperature-normalized rates of daily ecosystem respiration and gross-primary production  and

and  , and mass-corrected biomass using parameter estimates for the constrained model (table 1). Analyses revealed that temperature-corrected rates of ecosystem metabolism increased with mass-corrected biomass for both gross primary production and ecosystem respiration (figure 2). However, the unconstrained OLS regression slopes of these log–log relationships were significantly less than the predicted value of unity (p < 0.05), indicating deviations from the assumptions of the model. Neither the slopes, nor the intercepts, of the linear models differed between the ambient and warmed treatments for gross primary production (ANCOVA, p > 0.08). By contrast, for ecosystem respiration, the slope and intercepts did differ (ANCOVA, p < 0.05) and the data from the ambient treatments were consistent with model predictions (figure 2).

, and mass-corrected biomass using parameter estimates for the constrained model (table 1). Analyses revealed that temperature-corrected rates of ecosystem metabolism increased with mass-corrected biomass for both gross primary production and ecosystem respiration (figure 2). However, the unconstrained OLS regression slopes of these log–log relationships were significantly less than the predicted value of unity (p < 0.05), indicating deviations from the assumptions of the model. Neither the slopes, nor the intercepts, of the linear models differed between the ambient and warmed treatments for gross primary production (ANCOVA, p > 0.08). By contrast, for ecosystem respiration, the slope and intercepts did differ (ANCOVA, p < 0.05) and the data from the ambient treatments were consistent with model predictions (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between (a) temperature-corrected daily gross primary production and mass-corrected autotroph community biomass, and (b) temperature-corrected daily ecosystem respiration and total mass-corrected biomass. Fluxes were temperature normalized using the empirically derived values of Ep = 0.39 eV in (a) and ER = 0.60 eV in (b) (table 1). The heated and ambient treatments are denoted by filled circles and ambient treatments by open circles. Analysis reveals that mass-corrected community biomass and ecosystem flux are positively correlated, after correcting daily fluxes for the influence of temperature. The solid lines in these panels correspond to predictions of the constrained model, which was fitted (see table 1 for parameter estimates) based on equations (3.3)–(3.6), whereas the dashed lines are unconstrained OLS regression models fitted to the bivariate relationships (parameter estimates and statistics listed in the figure panels). Regression models for gross primary production, and ecosystem respiration in the warmed treatments yield slopes that differ significantly from the model predictions (p < 0.01), while the model for ecosystem respiration in the ambient treatments yielded a slope that was consistent with the theory.

The third prediction is that the mass-dependence of metabolic rate, characterized by α, should be less than unity, implying that the total rate of ecosystem metabolism (i.e. P and R) increases sub-linearly with total standing biomass, reflecting nonlinear declines in organelle densities and mass-specific metabolic rate with increasing body size [24]. The allometric exponent that provided the best fit to the data was α = 0.426 (table 1), which is less than unity, but also significantly lower than the ‘canonical’ value of α = 0.75 that is typically observed for metazoans [42].

(b). Reconciling the long-term temperature dependence of ecosystem metabolism with community size structure

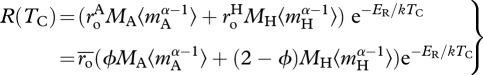

We now consider how community size structure can modulate the temperature dependence of ecosystem respiration and gross primary production over annual time-scales. For ecosystems that are at steady state on an annual basis and that receive few allochthonous subsidies, annual ecosystem respiration, τ〈R(T)〉τ, is constrained to be approximately equal to annual gross primary production, τ〈P(T)〉τ, such that

|

3.7 |

where  is the integral of the Boltzmann factor with respect to temperature variation through time, T(t), over the time interval 0 to τ [27].

is the integral of the Boltzmann factor with respect to temperature variation through time, T(t), over the time interval 0 to τ [27].

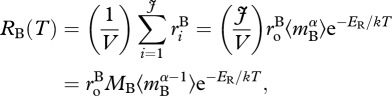

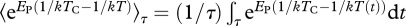

Equation (3.7) yields three predictions. The first prediction, which arises from a steady-state assumption [24], is that ecosystem respiration and gross primary production should show a one-to-one relationship. The mesocosm data provide some support for this prediction. In both the warmed and ambient mesocosms, annual ecosystem respiration was positively correlated with annual gross primary production (figure 3). Furthermore, the average ratio of annual ecosystem respiration to gross primary production was indistinguishable from unity in the warmed mesocosms ( 95% CI = 0.88–1.06; table 2), implying that these ecosystems were approximately at steady state. In the ambient systems, by contrast, this ratio was significantly less than unity (

95% CI = 0.88–1.06; table 2), implying that these ecosystems were approximately at steady state. In the ambient systems, by contrast, this ratio was significantly less than unity ( 95% CI = 0.76–0.87; table 2), meaning the ambient mesocosms served as carbon sinks on an annual basis.

95% CI = 0.76–0.87; table 2), meaning the ambient mesocosms served as carbon sinks on an annual basis.

Figure 3.

Relationship between annually integrated ecosystem respiration and gross primary production for heated (filled circles) and ambient treatments (open circles). Dashed line represents y = x. For both heated and ambient treatments, ecosystem respiration and gross primary production were significantly correlated. However, analysis of these data reveal that the ratio of ecosystem respiration to gross primary production is significantly less than unity in the ambient treatments, while in the heated treatments this ratio is indistinguishable from unity and they are therefore at steady state on an annual basis.

Table 2.

Results of the linear mixed effects model analysis—models were fitted using the lme function in the nlme package for R. The random effects structure is given for the model. A first-order autoregressive function (corAR1) was used to model the temporal autocorrelation in the data that arose from making repeated measurements on replicates. The results of the model selection procedure on the fixed effect terms are also given and the most parsimonious models are highlighted in bold. Analysis revealed that the metabolic balance (R/P) varied significantly between treatments and months, though the interaction between treatment and month was not significant.

| model | d.f. | AIC | logLik | L-ratio | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| random effects structure | |||||

| random = ∼ 1|mesocosm, | |||||

| corrected structure = corAR1 (month|mesocosm) | |||||

| fixed effects structure | |||||

| 1. ln(R/P) ∼1 + month × treat | 17 | −28.5 | 31.3 | ||

| 2. ln(R/P) ∼1 + month + treat | 11 | −38.8 | 30.4 | 1.7 | 0.95 |

| 3. ln(R/P) ∼1 + treat | 5 | −9.3 | 9.7 | 41.5 | <0.0001 |

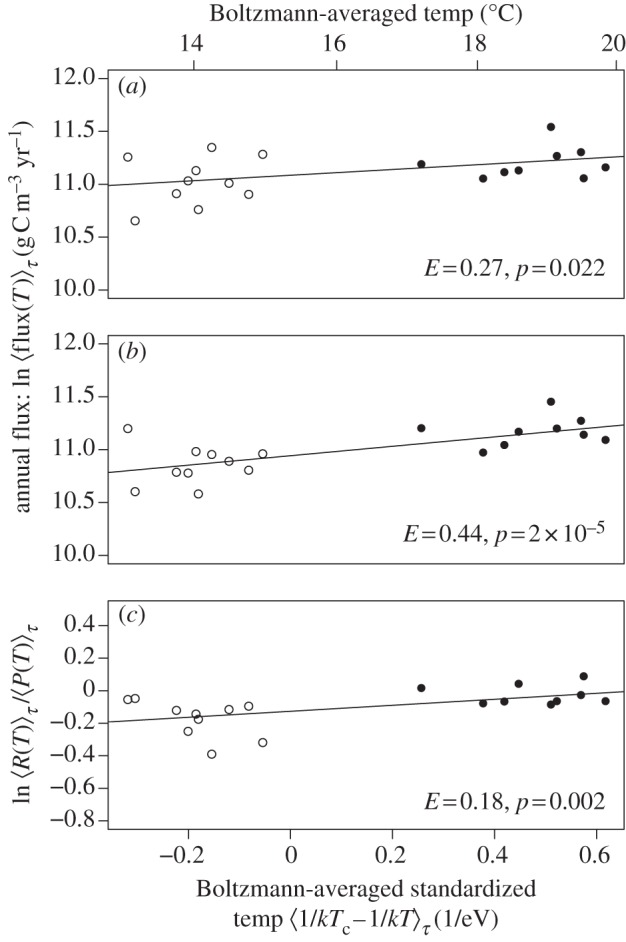

The second prediction is that both long-term ecosystem respiration and gross primary production should be governed by the temperature dependence of photosynthesis provided that the steady-state assumption is upheld. Given that this assumption was only upheld for the warmed mesocosms (figure 3 and table 2), and that the warming treatment was the primary determinant of temperature-dependent variation in annual flux among mesocosms (figure 4a,b), it was not surprising that the temperature dependence of annual ecosystem respiration was significantly stronger than that of gross primary production (likelihood ratio test on nested models  p = 0.023). Consequently, the metabolic balance of these ecosystems was temperature-dependent, such that the carbon sequestration capacity declined at higher temperatures (figure 4c).

p = 0.023). Consequently, the metabolic balance of these ecosystems was temperature-dependent, such that the carbon sequestration capacity declined at higher temperatures (figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Long-term temperature dependencies of (a) gross primary production, (b) ecosystem respiration, and (c) the ratio of annual ecosystem respiration to gross primary production, all of which were estimated using Boltzmann-averaged temperature kinetics (see §5). Analysis revealed that the long-term temperature dependence of ecosystem respiration was significantly stronger than that of gross primary production ( p = 0.023), resulting in a temperature-dependent metabolic balance (i.e. R/P), which differed from the prediction of our model assuming a long-term steady state between these variables.

p = 0.023), resulting in a temperature-dependent metabolic balance (i.e. R/P), which differed from the prediction of our model assuming a long-term steady state between these variables.

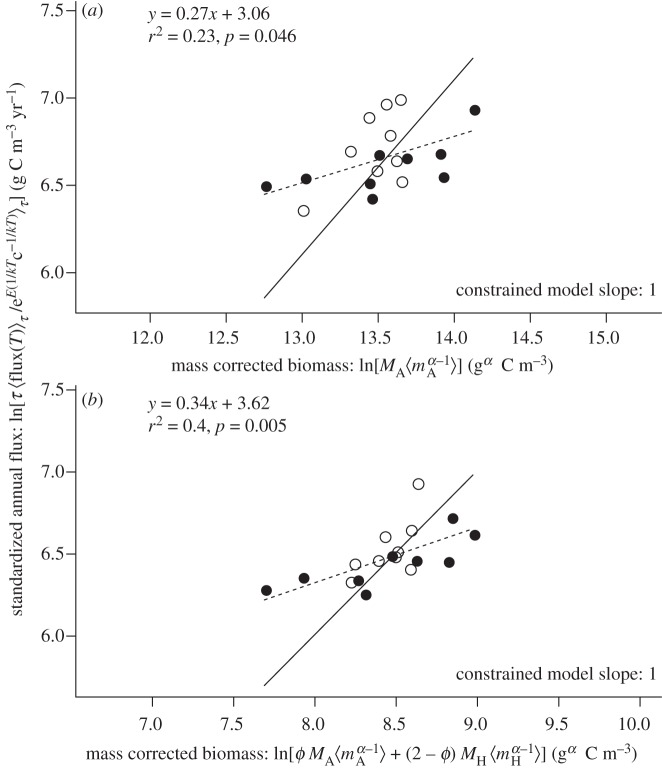

The third prediction is that gross primary production and ecosystem respiration should increase proportionally with the expressions used to quantify mass-corrected biomass of autotrophs and the entire ecosystem, respectively. This prediction was qualitatively, but not quantitatively, supported by our experimental data (figure 5). Both gross primary production and ecosystem respiration were significantly correlated with mass-corrected biomass after correcting for temperature. However, in contrast to expectations based on equation (3.7), both variables exhibited sub-linear scaling, rather than proportional scaling with the mass-corrected biomass terms.

Figure 5.

Relationships of mass-corrected community biomass to (a) temperature-corrected annual gross primary production, and (b) annual ecosystem respiration. Both fluxes are significantly correlated with biomass, although the slopes of the OLS-fitted regression models (dashed lines) are significantly less than the value of unity (p < 0.05) predicted by the constrained model (solid line; table 1), indicating qualitative, but not quantitative, support for the model predictions.

4. Discussion

Understanding and quantifying the mechanisms that link the structure of biotic communities to the flux, storage and turnover of energy and elements in ecosystems is among the greatest challenges in ecology [18,20,31,43]. Here we have addressed this issue by analysing experimental mesocosm data using a mechanistic model of the carbon cycle that yields quantitative predictions by scaling metabolism from individuals to ecosystems [24,27]. Our analysis revealed that seasonal variations in photosynthesis and respiration were strongly influenced by temperature, and reflected the average activation energies of these metabolic fluxes at the sub-cellular level, consistent with the primary role of temperature as a driver of physiological rate processes [25,38]. However, neither of these temperature dependencies were affected by the warming treatment (figure 1). On the other hand, warming significantly shifted the balance between ecosystem respiration and gross primary production on an annual basis. In the warmed mesocosms, ecosystem respiration and gross primary production reached approximate steady state, while the ambient systems were net carbon sinks on an annual basis (figure 3). These findings highlight that the different temperature dependencies of photosynthesis and respiration at the individual level can have important implications for ecosystem-level carbon sequestration.

Annually integrated rates of both gross primary production and ecosystem respiration were significantly correlated with community size structure both within and among the ambient and warmed temperature treatments (figure 5). This is because, ultimately, long-term fluxes are driven by the abundance, biomass and body size distribution of the organisms that comprise the ecosystem. These findings are particularly significant given that all of the mesocosms were seeded with identical communities of organisms and experienced similar colonization histories by biota for more than 1 year prior to commencement of the experiment. Our analyses therefore illustrate that even relatively small differences in community size structure (mass corrected biomass spans <1 order of magnitude in figure 5) can have significant, measurable effects on annual biogeochemical cycling rates. Owing to our experimental design, it was not possible to ascertain the extent to which seasonal variation in ecosystem fluxes was influenced by community size structure. However, given the short generation times of most organisms comprising the biota of these mesocosms (e.g. hours to weeks), size structure may be of importance at shorter time-scales as well. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of using the mass and temperature dependence of individual metabolism to predict feedbacks between anthropogenic change, community structure and ecosystem functioning (see also Rall et al. [44] and Perkins et al. [45] for other examples of this approach).

While many of the model predictions were generally supported by the experimental data, the model did not of course capture all of the variability observed, and not all fitted parameter estimates matched our expectations. With respect to temperature, seasonal variation in gross primary production and ecosystem respiration normalized for mass-corrected biomass, closely matched a priori predictions based on the activation energies of photosynthetic and respiratory reactions [24]. On the contrary, while temperature normalized rates of ecosystem metabolism were correlated with estimates of mass-corrected biomass they also generally exhibited sub-linear scaling with these quantities, providing only qualitative support for our model's predictions. Similarly, with respect to size, there were clear deviations from the model's predictions, and the estimated size dependence of individual metabolism (α = 0.426, table 1) was markedly lower than values typically observed for metazoans [46] and unicellular organisms [33].

These deviations may, at least in part, reflect an incomplete empirical characterization of the mesocosm communities temporally, spatially and taxonomically. Analysis of the plankton community spanned the nano-plankton to macro-zooplankton; pico-plankton, bacteria (less than 2 μm) and macroalgae were not analysed, but often account for major portions of the total standing biomass and metabolic fluxes in aquatic ecosystems, particularly in shallow lakes [47–49]. Additionally, the temporal resolution of our characterization of community structure was far coarser than the generation times of most organisms comprising these communities. Assaying all the organisms that contribute significantly to biogeochemical cycles over the spatial extent of an ecosystem remains a significant challenge for empiricists and experimentalists interested in comprehensively understanding the links between community structure and ecosystem functioning.

As the limitations of the present study demonstrate, a great deal of empirical and theoretical work is still required to develop a complete, general theory that links the structure, dynamics and functioning of ecosystems. Nevertheless, recent work [12,24,25,27,31,39], including the theory and analyses presented here, have begun to make inroads into this fundamental question in ecology. Progress in this area promises to enable more accurate forecasting of the impact of anthropogenic processes on the ecosystem services controlled by biota [15]. In our increasingly modified world, overcoming this challenge is of paramount importance to securing to our long-term future, and that of the planet's biodiversity.

5. Statistical methods

The combined effects of community size structure and temperature on the seasonal variation in gross primary production and ecosystem respiration were assessed using a Bayesian modelling approach. For this study, the key advantage of the Bayesian methodology was that it allowed us to simultaneously estimate all of the parameters in equations (3.3) and (3.6) (estimates listed in table 1), and quantities derived from these parameters (e.g. mass-corrected biomass). It also allowed us to explicitly take into account statistical uncertainties in the parameter estimates, correlations among parameters and the nested nature of the data, which reflected more frequent sampling of some variables (i.e. temperature, P, R) than others (i.e. size-structure) for individual mesocosms.

Bayesian model fitting was undertaken by conducting a minimum of 100 000 MCMC iterations using JAGS v. 3.1.0 (Just Another Gibbs Sampler), in R statistical software using the R package ‘rjags’. Bayesian models were specified using the BUGS language [50]. Output from the MCMC runs was subsequently analysed using the R package ‘R2jags’ to verify convergence. Convergence was also assessed by visually inspecting posterior distributions of parameters to ensure the existence of well-defined modes. Given that parameters were assigned vague priors, the modes of posterior distributions correspond closely to the maximum-likelihood estimates (see BUGS code in the electronic supplementary material) [51].

The effects of warming on the ratio of ecosystem respiration to gross primary production were assessed using linear mixed effects models [52]. In the model, sampling date and experimental treatment were treated as fixed effects, while the intercepts were treated as random variables that could potentially vary among mesocosms. This random effect structure allowed us to account for the nested structure of the data—i.e. mesocosm-level relationships nested within the overall experimental-level relationship. We also included a first-order auto-regressive function to model the temporal correlation structure of the data (see table 1 for model specification) [52]. Significance of the fixed effects was assessed by adopting a top-down model selection procedure, which entailed fitting the most complex model to the data and then sequentially deleting non-significant terms until the most parsimonious model was found [53]. Model selection was carried out by comparing nested models (fitted with maximum likelihood) using the likelihood ratio test (see table 2 for the results of the model selection procedure).

The long-term temperature dependencies of ecosystem respiration and gross primary production (figure 4) were determined using maximum likelihood by calculating Boltzmann-averaged temperature kinetics,  [27]. Using Boltzmann-averaging to characterize kinetics is preferable to estimating kinetics using arithmetic mean annual temperature because this entails an approximation that becomes less accurate as seasonal variation in temperature increases [42]. This method used the annually integrated Boltzmann factor with the observed annual distribution of temperature to generate predicted values of annual flux, Pr, for each mesocosm [27]. Given the predicted values, Pr, and the observed annual fluxes, Or, for all n replicates, r, we then calculated the log-likelihood, L, as

[27]. Using Boltzmann-averaging to characterize kinetics is preferable to estimating kinetics using arithmetic mean annual temperature because this entails an approximation that becomes less accurate as seasonal variation in temperature increases [42]. This method used the annually integrated Boltzmann factor with the observed annual distribution of temperature to generate predicted values of annual flux, Pr, for each mesocosm [27]. Given the predicted values, Pr, and the observed annual fluxes, Or, for all n replicates, r, we then calculated the log-likelihood, L, as  where f(lnOr

− lnPr) is the log of the probability density for a deviation of magnitude lnOr − lnPr from a normal distribution of mean = 0. We then repeated this procedure using different values of E until the parameter estimate that maximized L was found. The difference between the long-term temperature dependencies of ecosystem respiration and gross primary production was assessed using a similar likelihood-based approach to that described above. This time, however, the data for the relationship between ecosystem respiration, gross primary production and temperature was fitted to a model with differential temperature dependencies for respiration and primary production, and a model with a single temperature dependence. These nested models were compared using the likelihood ratio test to determine whether the more complex model—with different slopes—yielded a significantly better fit.

where f(lnOr

− lnPr) is the log of the probability density for a deviation of magnitude lnOr − lnPr from a normal distribution of mean = 0. We then repeated this procedure using different values of E until the parameter estimate that maximized L was found. The difference between the long-term temperature dependencies of ecosystem respiration and gross primary production was assessed using a similar likelihood-based approach to that described above. This time, however, the data for the relationship between ecosystem respiration, gross primary production and temperature was fitted to a model with differential temperature dependencies for respiration and primary production, and a model with a single temperature dependence. These nested models were compared using the likelihood ratio test to determine whether the more complex model—with different slopes—yielded a significantly better fit.

The relationships between ecosystem metabolism and mass-corrected community biomass in both the short- (figure 2) and the long-term (figure 5) analyses were assessed using analysis of covariance to determine whether the slopes or intercepts of the models differed between treatments and from model predictions. Estimates of mass-corrected biomass for autotrophs,  , and the entire community,

, and the entire community,  used in these analyses were derived directly from the Bayesian analysis described above.

used in these analyses were derived directly from the Bayesian analysis described above.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jose M. Montoya, Guy Woodward and Mark Trimmer for discussions that have influenced the ideas presented here. We also thank Brian Godfrey, John Davy-Bowker and the Freshwater Biological Association of the UK for site maintenance and upkeep of the mesocosm experiment, as well as Daniel Perkins for field assistance. G.Y.-D. was supported by a Natural Environment Research Council UK grant awarded to Mark Trimmer (grant: NE/F004753/1).

References

- 1.Tansley A. 1935. The use and abuse of vegetational concepts and terms. Ecology 16, 284–307 10.2307/1930070 (doi:10.2307/1930070) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odum E. 1953. Fundamentals of ecology. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Niel R., DeAngelis D., Waide J., Allen T. 1986. A hierarchical concept of ecosystems. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones C., Lawton J. 1992. Linking species and ecosystems. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall [Google Scholar]

- 5.Likens G. E. 1992. The ecosystem approach: its use and abuse. Oldendorf, Germany: Ecology Institute, Oldendorf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindeman R. 1942. The trophic dynamic aspect of ecology. Ecology 23, 399–418 10.2307/1930126 (doi:10.2307/1930126) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elton C. 1927. Animal ecology. New York, NY: Macmillan [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacArthur R. 1955. Fluctuations of animal populations and a measure of community stability. Ecology 36, 533–536 10.2307/1929601 (doi:10.2307/1929601) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacArthur R. 1960. On the relative abundance of species. Am. Nat. 94, 25–36 10.1086/282106 (doi:10.1086/282106) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacArthur R. 1972. Geographical ecology: patterns in the distribution of species. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montoya J. M., Pimm S. L., Solé R. V. 2006. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature 442, 259–264 10.1038/nature04927 (doi:10.1038/nature04927) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shurin J. B., Clasen J. L., Greig H. S., Kratina P., Thomson P. L. 2012. Warming shifts top-down and bottom-up control of pond food web structure and function. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 3008–3017 10.1098/rstb.2012.0243 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0243) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentice I. C., Farquhar G. D., Fasham M. J. R., Goulden M. L., Heimann M., Jaramillo V. J., Kheshgi H. S., Scholes R. J., Wallace D. W. R. 2001. The carbon cycle and atmospheric carbon dioxide In Climate change 2001: the scientific basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed. Houghton J. T.), pp. 183–237 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodward G., et al. 2010. Ecological networks in a changing climate. Adv. Ecol. Res. 42, 71–138 10.1016/B978-0-12-381363-3.00002-2 (doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-381363-3.00002-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brose U., Dunne J. A., Montoya J. M., Petchey O. L., Schneider F. D., Jacob U. 2012. Climate change in size-structured ecosystems. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 2903–2912 10.1098/rstb.2012.0232 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0232). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitousek P., Mooney H., Lubchenco J., Melillo J. 1997. Human domination of Earth's ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499 10.1126/science.277.5325.494 (doi:10.1126/science.277.5325.494) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naeem S., Thomson L., Lawler S., Lawton J., Woodfin R. 1994. Declining biodiversity can alter the performance of ecosystems. Nature 368, 734–737 10.1038/368734a0 (doi:10.1038/368734a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loreau M., et al. 2001. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science 294, 804–808 10.1126/science.1064088 (doi:10.1126/science.1064088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiss J., Bridle J. R., Montoya J. M., Woodward G. 2009. Emerging horizons in biodiversity and ecosystem functioning research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 505–514 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.018 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper D., et al. 2005. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol. Monogr. 75, 3–35 10.1890/04-0922 (doi:10.1890/04-0922) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGill B., Enquist B., Weiher E., Westoby M. 2006. Rebuilding community ecology from functional traits. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 178–185 10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.002 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White E. P., Ernest S. K. M., Kerkhoff A. J., Enquist B. J. 2007. Relationships between body size and abundance in ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 323–330 10.1016/j.tree.2007.03.007 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.03.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yvon-Durocher G., Reiss J., Blanchard J., Ebenman B., Perkins D. M., Reuman D. C., Thierry A., Woodward G., Petchey O. L. 2011. Across ecosystem comparisons of size structure: methods, approaches and prospects. Oikos 120, 550–563 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.18863.x (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.18863.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen A. P., Gillooly J. F., Brown J. H. 2005. Linking the global carbon cycle to individual metabolism. Funct. Ecol. 19, 202–213 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.00952.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.00952.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enquist B., Economo E., Huxman T., Allen A., Ignace D., Gillooly J. 2003. Scaling metabolism from organisms to ecosystems. Nature 423, 639–642 10.1038/nature01671 (doi:10.1038/nature01671) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown J., Gillooly J., Allen A., Savage V., West G. 2004. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85, 1771–1789 10.1890/03-9000 (doi:10.1890/03-9000) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yvon-Durocher G., et al. 2012. Reconciling the temperature dependence of respiration across time scales and ecosystem types. Nature 487, 472–476 10.1038/nature11205 (doi:10.1038/nature11205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yvon-Durocher G., Montoya J. M., Trimmer M., Woodward G. 2011. Warming alters the size spectrum and shifts the distribution of biomass in freshwater ecosystems. Global Change Biol. 17, 1681–1694 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02321.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02321.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yvon-Durocher G., Jones J. I., Trimmer M., Woodward G., Montoya J. M. 2010. Warming alters the metabolic balance of ecosystems. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 2117–2126 10.1098/rstb.2010.0038 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0038) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staehr P. A., Bade D., Van de Bogert M. C., Koch G. R., Williamson C., Hanson P., Cole J. J., Kratz T. 2010. Lake metabolism and the diel oxygen technique: state of the science. Limnol. Oceanogr. Method 8, 628–644 10.4319/lom.2010.8.628 (doi:10.4319/lom.2010.8.628) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enquist B. J., West G. B., Brown J. H. 2009. Extensions and evaluations of a general quantitative theory of forest structure and dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7046–7051 10.1073/pnas.0812303106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0812303106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehnes R. B., Rall B. C., Brose U. 2011. Phylogenetic grouping, curvature and metabolic scaling in terrestrial invertebrates. Ecol. Lett. 14, 993–1000 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01660.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01660.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeLong J. P., Okie J. G., Moses M. E., Sibly R. M., Brown J. H. 2010. Shifts in metabolic scaling, production, and efficiency across major evolutionary transitions of life. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12 941–12 945 10.1073/pnas.1007783107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1007783107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez-Urrutia A., San Martin E., Harris R. P., Irigoien X. 2006. Scaling the metabolic balance of the oceans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8739–8744 10.1073/pnas.0601137103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0601137103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regaudie-de-Gioux A., Duarte C. M. 2012. Temperature dependence of planktonic metabolism in the ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB1015. 10.1029/2010GB003907 (doi:10.1029/2010GB003907) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson-Teixeira K. J., DeLong J. P., Fox A. M., Brese D. A., Litvak M. E. 2011. Differential responses of production and respiration to temperature and moisture drive the carbon balance across a climatic gradient in New Mexico. Global Change Biol. 17, 410–424 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02269.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02269.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Downs C. J., Hayes J. P., Tracy C. R. 2008. Scaling metabolic rate with body mass and inverse body temperature: a test of the Arrhenius fractal supply model. Funct. Ecol. 22, 239–244 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01371.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01371.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillooly J. F. H., Brown J. F., West G. B., Savage V. M., Charnov E. L. 2001. Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. Science 293, 2248–2251 10.1126/science.1061967 (doi:10.1126/science.1061967) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen A. P., Gillooly J. F. 2009. Towards an integration of ecological stoichiometry and the metabolic theory of ecology to better understand nutrient cycling. Ecol. Lett. 12, 369–384 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01302.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01302.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demars B. O. L., et al. 2011. Temperature and the metabolic balance of streams. Freshwater Biol. 56, 1106–1121 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2010.02554.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2010.02554.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkins D. M., Yvon-Durocher G., Demars B. O. L., Reiss J., Pichler D. E., Friberg N., Trimmer M., Woodward G. 2012. Consistent temperature dependence of respiration across ecosystems contrasting in thermal history. Global Change Biol. 18, 1300–1311 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02597.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02597.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savage V. H. 2004. Improved approximations to scaling relationships for species, populations, and ecosystems across latitudinal and elevational gradients. J. Theor. Biol. 227, 525–534 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.11.030 (doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.11.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall E. K., Maixner F., Franklin O., Daims H., Richter A., Battin T. 2011. Linking microbial and ecosystem ecology using ecological stoichiometry: a synthesis of conceptual and empirical approaches. Ecosystems 14, 261–273 10.1007/s10021-010-9408-4 (doi:10.1007/s10021-010-9408-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rall B. C., Brose U., Hartvig M., Kalinkat G., Schwarzmüller F., Vucic-Pestic O., Petchey O. L. 2012. Universal temperature and body-mass scaling of feeding rates. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 2923–2934 10.1098/rstb.2012.0242 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0242) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins D. M., Mckie B. G., Malmqvist B., Gilmour S. G., Reiss J., Woodward G. 2010. Environmental warming and biodiversity-ecosystem functioning in freshwater microcosms: partitioning the effects of species identity, richness and metabolism. Adv. Ecol. Res. 41, 177–209 (doi:10.1016/S0065–2504(10)43005-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savage V., Gillooly J., Woodruff W., West G., Allen A., Enquist B., Brown J. 2004. The predominance of quarter-power scaling in biology. Funct. Ecol. 18, 257–282 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00856.x (doi:10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00856.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li W., Rao D., Harrison W., Smith J., Cullen J., Irwin B., Platt T. 1983. Autotrophic picoplankton in the tropical ocean. Science 219, 292–295 10.1126/science.219.4582.292 (doi:10.1126/science.219.4582.292) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moran X. A. G., Lopex-Urrutia Á., Calvo-Diaz A., Li W. K. W. 2010. Increasing importance of small phytoplankton in a warmer ocean. Global Change Biol. 16, 1137–1144 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01960.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01960.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moss B. 2011. Cogs in the endless machine: lakes, climate change and nutrient cycles: a review. Sci. Total Environ 434, 130–142 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.069 (doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lunn D., Spiegelhalter D., Thomas A., Best N. 2009. The BUGS project: evolution, critique and future directions. Stat. Med. 28, 3049–3067 10.1002/sim.3680 (doi:10.1002/sim.3680) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gelman A., Carlin J. B., Stern H. S., Rubin D. B. 2003. Bayesian data analysis, 2nd edn Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinheiro J., Bates D. M. 2000. Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuur A., Ieno E., Walker N., Saveliev A. 2009. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]