Abstract

We investigated Zn compartmentation in the root, Zn transport into the xylem, and Zn absorption into leaf cells in Thlaspi caerulescens, a Zn-hyperaccumulator species, and compared them with those of a related nonaccumulator species, Thlaspi arvense. 65Zn-compartmental analysis conducted with roots of the two species indicated that a significant fraction of symplasmic Zn was stored in the root vacuole of T. arvense, and presumably became unavailable for loading into the xylem and subsequent translocation to the shoot. In T. caerulescens, however, a smaller fraction of the absorbed Zn was stored in the root vacuole and was readily transported back into the cytoplasm. We conclude that in T. caerulescens, Zn absorbed by roots is readily available for loading into the xylem. This is supported by analysis of xylem exudate collected from detopped Thlaspi species seedlings. When seedlings of the two species were grown on either low (1 μm) or high (50 μm) Zn, xylem sap of T. caerulescens contained approximately 5-fold more Zn than that of T. arvense. This increase was not correlated with a stimulated production of any particular organic or amino acid. The capacity of Thlaspi species cells to absorb 65Zn was studied in leaf sections and leaf protoplasts. At low external Zn levels (10 and 100 μm), there was no difference in leaf Zn uptake between the two Thlaspi species. However, at 1 mm Zn2+, 2.2-fold more Zn accumulated in leaf sections of T. caerulescens. These findings indicate that altered tonoplast Zn transport in root cells and stimulated Zn uptake in leaf cells play a role in the dramatic Zn hyperaccumulation expressed in T. caerulescens.

Phytoextraction is an emerging technology that involves the use of vascular plants to remediate soils contaminated with heavy metals and/or radionuclides (Nanda Kumar et al., 1995). This approach is based on the ability of higher plants to absorb contaminants from the soil and translocate them to their shoots. The identification of several metal-hyperaccumulator plant species (Baker and Brooks, 1989; Baker et al., 1998) demonstrates that the genetic potential exists for successful phytoremediation of contaminated soils. One of the best-known metal hyperaccumulators is Thlaspi caerulescens J&C Presl, which has been reported to have a great potential for extraction of Zn and Cd from metalliferous soils (Reeves and Brooks, 1983; Chaney, 1993; Baker et al., 1994; Brown et al., 1994, 1995a, 1995b). Recently, Brown et al. (1995b) reported that from a hydroponic medium, T. caerulescens accumulated more than 25,000 μg Zn g−1 before symptoms of Zn toxicity (i.e. shoot biomass reduction) occurred.

Although T. caerulescens has the ability to transfer high levels of Zn and other metals from the soil into the shoot, the use of this species for commercial remediation of contaminated soils is severely limited by its small size and slow growth (Ebbs et al., 1997). The transfer of Zn-hyperaccumulating properties from T. caerulescens into a high-biomass-producing plant has been suggested as a potential avenue for making phytoremediation a commercial technology (Brown et al., 1995a). Progress in this area, however, is hindered by a lack of understanding of the basic physiological mechanisms involved in Zn uptake into roots and translocation to aboveground tissues.

In a previous study we reported that Zn influx into root symplasm of Zn-hyperaccumulator and -nonaccumulator species of Thlaspi was mediated by a saturable component with similar affinities for Zn (Lasat et al., 1996). However, the maximum capacity for Zn transport across the plasma membrane into the cytosol was 4.5-fold greater in the Zn-accumulator T. caerulescens compared with the Zn-nonaccumulator Thlaspi arvense L. These results indicate that one characteristic of T. caerulescens is a greater capacity for Zn absorption from soil solution into root cells. Enhanced Zn uptake into the root symplasm of T. caerulescens was also associated with a greater capacity for Zn translocation to the shoot (Lasat et al., 1996). For example, after 96 h of exposure to a 65Zn-labeled uptake solution, 10-fold more 65Zn accumulated in the shoots of T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense, and 1.2-fold more 65Zn accumulated in the roots of T. arvense compared with T. caerulescens. These results suggest that in addition to Zn entry into the root symplasm, other Zn-transport sites are altered in T. caerulescens, contributing to the dramatic increase in Zn translocation and storage in the shoot.

We used hydroponically grown T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings to investigate several mechanisms possibly involved in Zn hyperaccumulation: (a) stimulated Zn transport from the root symplasm into the xylem sap; (b) xylem accumulation of low-Mr organic ligands possibly involved in Zn complexation and transport to the shoot; and (c) enhanced Zn transport into leaf cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Seeds of Thlaspi arvense were obtained from the Crucifer Genetics Cooperative (University of Wisconsin, Madison). Thlaspi caerulescens seeds were obtained from plants grown near a Zn/Cd smelter in Prayon, Belgium (Vázquez et al., 1994). Seeds were grown hydroponically in 5-L black plastic tubs as described previously (Lasat et al., 1996). To obtain seedlings of similar size and developmental status, T. caerulescens seedlings were used when they were 5 to 10 d older than T. arvense seedlings. Seedlings were detopped for collection of xylem sap and grown in a nutrient solution with either a control level of Zn2+ (1 μm) or supplemented with 50 μm Zn2+ (as ZnCl2).

Short-Term 65Zn-Efflux (Compartmentation) Studies

Seedlings of 40-d-old T. arvense and 45-d-old T. caerulescens were incubated with roots in Plexiglas uptake wells filled with 85 mL of the aerated uptake solution containing 2 mm Mes-Tris buffer (pH 6.0), 0.5 mm CaCl2, and 20 μm 65Zn2+ (1.4 μCi L−1) (as ZnCl2). After 24 h the radioactive uptake solution was removed, roots were quickly rinsed with deionized water, and wells were refilled with an efflux solution that was identical to the radioisotope-loading solution except that it lacked 65Zn (2 mm Mes-Tris buffer, pH 6.0, 0.5 mm CaCl2, and 20 μm Zn2+). At various time intervals, a 1-mL aliquot of the efflux solution was collected and 65Zn was measured with a gamma counter (model 5530, Packard Instruments, Downers Grove, IL). After the removal of each aliquot, wells were drained and refilled with fresh efflux solution. After 6 h roots were excised, blotted, and weighed, and root 65Zn content was determined. The efflux of 65Zn2+ from roots was determined by monitoring the appearance of 65Zn in the efflux solution over time.

Long-Term 65Zn-Efflux Studies

Roots of intact T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings were incubated for 24 h in a plastic container filled with 800 mL of the aerated uptake solution containing 20 μm 65Zn2+ (1.4 μCi L−1). After 24 h the radioactive solution was removed, roots were rinsed with deionized water, and the container was refilled with nonradiolabeled efflux solution. At various time intervals up to 46 h, four T. arvense and four T. caerulescens seedlings were harvested and roots were separated from shoots, blotted, and weighed, and root and shoot 65Zn was measured. After removal of each set of seedlings at the specific time intervals the efflux solution was replaced with fresh solution. Efflux from roots was assessed by determining the 65Zn remaining in roots over time.

Xylem Sap Collection and Analysis

Fifty-day-old T. arvense and 55-d-old T. caerulescens seedlings grown for the entire period in a nutrient solution containing 1 μm Zn2+ or transferred 10 d before the experiment to a similar nutrient solution supplemented with 50 μm Zn2+ were detopped just below the leaf rosette with a razor blade. The entire excised root system and remaining stem material were used for collection of xylem exudate. The excised stem surface was gently wiped, and a Pasteur pipette tip was sealed onto the cut end of the stem by applying a thin layer of high-vacuum grease (Dow-Corning Corp., Midland, MI). Xylem sap exuded into the pipette for the subsequent 24-h period was collected, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −70°C until analyzed. Zn content of the xylem sap was analyzed with an inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (model ICAP 61E, Thermo-Jarrell Ash, Waltham, MA).

To analyze organic acids in the xylem sap, we used an ion-chromatography system (model 300, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) with an ion-exchange analytical column (4 mm, model AS11, Dionex) and an eluent gradient of NaOH in 18% high-purity methanol. Organic acids were detected by determination of electrical conductivity. Identification and quantification of sample components were achieved by comparison of retention times in standard solutions and peak integration to fit into standard curves. The detection limit was 10 μm.

To analyze amino acids, xylem sap was dried under a vacuum and hydrolyzed with constant boiling in HCl at 116°C for 24 h. Hydrolyzed samples were dried under a vacuum, redissolved in 1:3 (v/v) 20 mm HCl:AccQ-Fluor borate buffer (Waters), and fluorescently derivatized with 1 volume of AccQ-Fluor for 10 min at 55°C. Samples were chromatographed using a liquid-chromatography system (Waters) with a C18 column (4 μm, Waters) according to the directions of the manufacturer. Derivatized amino acids were identified via fluorescence detection using an excitation wavelength of 250 nm and an emission wavelength of 395 nm. For most amino acids the detection limit was 10 μm; for Cys the detection limit was 5 μm.

65Zn2+ Uptake in Leaf Sections

Leaves were gently abraded with Carborundum powder (320-grit, Fisher Scientific) to facilitate infiltration of the radioactive uptake solution, thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to remove any adhering powder, and cut into 10- to 20-mm2 sections. Leaf material was then immersed in an aerated uptake solution containing 10, 100, or 1000 μm 65ZnCl2 (1.4 μCi L−1), 2 mm Mes-Tris buffer, pH 6.0, and 0.5 mm CaCl2. At different time intervals up to 48 h, 65Zn2+ uptake was terminated by replacing radioactive solution with desorption solution containing 5 mm CaCl2, 5 mm Mes-Tris, pH 6.0, and 100 μm ZnCl2. After 15 min of desorption to remove apoplastic 65Zn, leaf sections were harvested, blotted, and weighed, and leaf 65Zn content was measured via gamma detection.

65Zn Uptake in Leaf Protoplasts

Protoplast Isolation

Leaves (4 g fresh weight) were gently abraded with Carborundum powder, rinsed thoroughly with deionized water to remove adhering powder, and chopped into fine pieces using a razor blade. Chopped tissues were suspended in 25 mL of a cell wall-digesting medium composed of 600 mm mannitol, 3 mm Mes-Tris buffer, pH 5.5, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm DTT, 0.7 mm KH2PO4, 0.1% (w/v) BSA, 1% (w/v) Cellulysin (Calbiochem), and 0.1% (w/v) Pectolyase (Sigma). The tissues were incubated at 20°C in the dark for 30 to 45 min. The resulting suspension was filtered through four layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem), and protoplasts were pelleted by centrifugation at 60g for 5 min at 2°C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet resuspended in protoplast buffer (600 mm mannitol, 3 mm Mes-Tris buffer [pH 5.5], 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm DTT, 0.7 mm KH2PO4, and 0.1% [w/v] BSA).

Protoplasts were washed in 20 mL of the protoplast buffer and centrifuged at 60g for 5 min, and then the supernatant was discarded and the pellet resuspended in the residual liquid. This step was repeated three times. After the last centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of preuptake solution consisting of 500 mm mannitol, 50 mm Suc, 3 mm Mes-Tris (pH 5.5), 0.05 mm CaCl2, 1 mm DTT, and 0.7 mm KH2PO4. The number of protoplasts was determined with a hemocytometer. The protoplast stock was kept in a test tube on ice until the uptake experiments were performed.

Determination of Protoplast Viability

The percentage of viable protoplasts in the stock was determined by staining with FDA used at a final concentration of 36 μm from a stock of 7.2 mm FDA dissolved in acetone (final acetone concentration was 0.5%, v/v). After 10 min of incubation in FDA, protoplasts were inspected using a fluorescence microscope (model IMT-2, Olympus). Protoplasts showing bright fluorescence were counted as viable. Protoplast viability ranged between 70% and 80%.

65Zn-Uptake Experiments with Protoplasts

The time course of 65Zn uptake was initiated by the addition of 900 μL of the protoplast stock to a 1.5-mL Eppendorf microcentrifuge tube with 100 μL of the preuptake solution containing 0.1, 1.0, or 10 mm 65ZnCl2 (0.5 μCi mL−1). Therefore, the 65Zn2+ concentration to which protoplasts were exposed was 10, 100, or 1000 μm (protoplast volume did not interfere with this dilution, because it represented less than 5% of the stock volume). The final protoplast concentration in the uptake solution was 2 × 107 protoplasts mL−1. At different time intervals up to 12 min, a 100-μL aliquot of the radioactive protoplast suspension was removed and placed on the top of a discontinuous gradient consisting of (from the top to the bottom of a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube) 50 μL of 10% (v/v) HClO4 on top of 400 μL of silicon oil (550 Fluid, Dow-Corning) with a specific density of 1.06 at 25°C. The microcentrifuge tubes were immediately centrifuged using a bench-top microcentrifuge (model 5415, Brinkmann Instruments) at high speed for 1 min to pellet the protoplasts through the silicon oil layer. After centrifugation, tubes were immersed in liquid N2. Tips containing the frozen protoplast pellet were cut off and placed in counting vials. The uptake of 65Zn2+ into protoplasts was quantified via gamma detection.

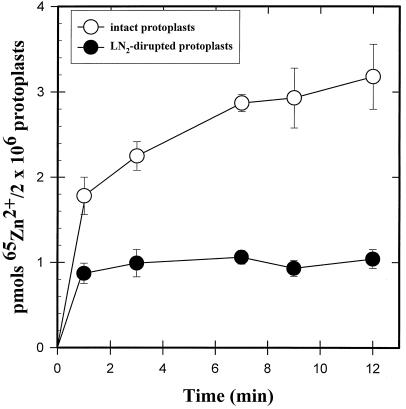

To determine whether Zn accumulation in protoplasts was caused by 65Zn2+ movement across the plasma membrane into the cytosol or by the binding of Zn to negatively charged sites associated with the external face of the plasma membrane, two different experiments were carried out. First, we conducted a study to investigate the time course of Zn uptake in intact versus ruptured T. arvense protoplasts. To rupture the plasma membrane, T. arvense protoplasts were frozen in liquid N2 and then thawed at room temperature. Microscopic inspection confirmed that after this treatment the protoplast stock had been entirely ruptured. The stock of ruptured and intact protoplasts was used to conduct a time-course study of 65Zn2+ uptake from a 10 μm Zn solution. In the second experiment, we investigated the effect of the protonophore and metabolic inhibitor CCCP on the time-dependent kinetics of 65Zn uptake in T. caerulescens protoplasts. In this experiment, 10 μm CCCP was added to the protoplast stock 30 min before the beginning of the experiment. The time-course study was conducted in an uptake solution containing 10 or 100 μm 65Zn2+, as described above.

RESULTS

Efflux Compartmentation Studies

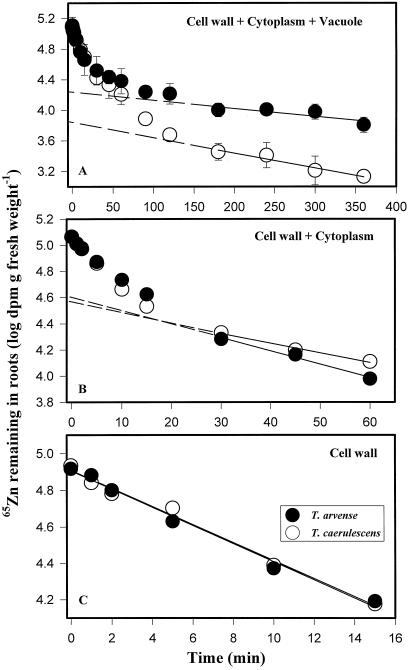

To investigate the subcellular compartmentation of 65Zn2+ in roots, we conducted a short-term (6 h) study on the time-dependent kinetics of 65Zn efflux from T. caerulescens and T. arvense roots. Plots representing a first-order kinetic transformation of Zn efflux (log 65Zn remaining in the root as a function of time) could be dissected into three linear phases representing Zn efflux from three compartments in series: the vacuole, cytoplasm, and cell wall (Fig. 1). The straight line drawn through data representing the slowest-exchanging phase (180–360 min) was interpreted to represent 65Zn efflux from the vacuole (Fig. 1A). From the slope of this line we estimated the half-time for 65Zn efflux from the vacuole (Table I). The y-axis intercept of this line was used to calculate the distribution of 65Zn in root cells at the termination of the radioisotope-loading period (Table I).

Figure 1.

Short-term efflux of 65Zn from roots of T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings. After a 24-h incubation in an uptake solution containing 20 μm 65Zn2+, roots were rinsed in deionized water, and, to initiate 65Zn efflux, the radioactive uptake solution was replaced with an identical, nonlabeled solution containing 20 μm Zn2+. Efflux of 65Zn from roots into the external solution was subsequently monitored for a 6-h period. Lines represent regressions of the linear portion of each curve extrapolated to the y axis. The curve shown in B was derived by subtracting the linear component in A from the data points in A. The curve in C was similarly derived from the curve in B. Data points in A represent means ± se of four replicates.

Table I.

Intracellular 65Zn2+ compartmentation and half-time (t1/2) for 65Zn2+ efflux from different root compartments from T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings

Subtraction of the linear component from total efflux data (Fig. 1A) yielded a second curve, which was analyzed similarly and was interpreted to represent 65Zn efflux from the cytoplasm (30–60 min) and cell wall (0–15 min) (Fig. 1B). Efflux from the cell wall (Fig. 1C) was obtained after subtracting the linear phase associated with the cytoplasmic efflux from the data points plotted in Figure 1B. Translocation of 65Zn to the shoots did not interfere with the compartmentation analysis, in that it represented only 0.7% and 2.5% of the total radioactive Zn accumulated in roots of T. arvense and T. caerulescens, respectively. At the end of a 24-h radioisotope-loading period, comparable amounts of 65Zn2+ had accumulated in the roots of the two Thlaspi species (first pair of data points in Fig. 1A).

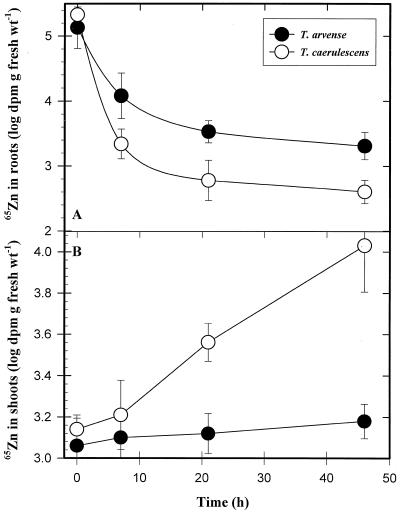

As shown in Table I, Zn compartmentation in the root cell wall and cytoplasm were similar in T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings; however, approximately 2.4-fold more 65Zn was accumulated in the root vacuole of T. arvense compared with T. caerulescens. Although the rates of 65Zn efflux from the cell wall and cytoplasm were similar in T. arvense and T. caerulescens, the half-time for radioactive Zn efflux from the vacuole was nearly 50% shorter in T. caerulescens, indicating that Zn efflux from the T. caerulescens root vacuole was almost twice as rapid as in T. arvense (Table I). In a long-term 65Zn efflux experiment, approximately 6-fold more 65Zn remained in T. arvense roots compared with T. caerulescens at the end of the 46-h washout period (Fig. 2A); however, at the end of the same period, 6-fold more 65Zn was translocated from the root to the shoot of T. caerulescens (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Long-term efflux of 65Zn from roots (A) and 65Zn translocation to shoots (B) of T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings. Bundles of four T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings were immersed with roots in a 20 μm 65Zn2+ uptake solution. After a 24-h loading period, roots were rinsed in deionized water, and the radioactive uptake solution was replaced with an identical, nonlabeled solution containing 20 μm Zn2+. At different time intervals up to 46 h, one bundle of each Thlaspi species was harvested, roots were excised, blotted, and weighed, and gamma activity was measured. Data points represent means ± se of four replicates. wt, Weight.

Analysis of Xylem Exudates

Relatively large volumes of xylem sap (approximately 5 mL from 15 to 20 plants) were collected from both Thlaspi species during the 24-h period after detopping. Regardless of the Zn concentration in the nutrient solution, significantly more Zn was accumulated in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense. For example, from the hydroponic growth solution containing 50 μm Zn2+, approximately 5-fold more Zn was found in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense (524 versus 100 μm Zn; Table II). A comparable ratio was found when the two Thlaspi species were grown in 1 μm Zn2+ (54 versus 15 μm; Table II). Both species accumulated Zn in the xylem to significantly higher concentrations when the Zn level in the growth solution was increased from 1 to 50 μm.

Table II.

Concentrations of Zn, organic acids, and amino acids in the xylem sap of T. arvense and T. caerulescens grown for the entire 55-d period in a nutrient solution containing 1 μm Zn2+ or for the last 10 d in the solution supplemented with 50 μm Zn2+

|

T.

arvense

|

T. caerulescens

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 μm Zn2+ | 50 μm Zn2+ | 1 μm Zn2+ | 50 μm Zn2+ | |

| Zn | 15 | 100 | 54 | 524 |

| Organic acidsa | ||||

| Acetate | 290 | 890 | 875 | 4140 |

| Malate | 130 | 250 | 150 | 170 |

| Amino acidsb | ||||

| Asp | — | — | — | 60 |

| Ser | 60 | — | — | — |

| Glu | 140 | — | 640 | 420 |

| His | 110 | 140 | — | — |

| Arg | 40 | 30 | — | 20 |

| Thr | 40 | — | — | 20 |

| Ala | 10 | 30 | 60 | 20 |

| Pro | 30 | 120 | — | 20 |

| Tyr | 20 | — | — | — |

| Val | 60 | — | 60 | 40 |

| Lys | 40 | 50 | — | — |

| Ile | 40 | — | 20 | 10 |

| Leu | 30 | — | — | 10 |

| Phe | 10 | 10 | 60 | 40 |

Aconitate, citrate, fumarate, pyruvate, and succinate were not detected in the xylem sap of either Thlaspi species. Detection limit was 10 μm for all organic acids.

Gly, Cys, and Met were not detected in the xylem sap of either Thlaspi species. The detection limit was 10 μm for all amino acids except Cys (5 μm detection limit).

The possibility that a significant amount of Zn moving to the T. caerulescens shoot was complexed or associated with one or more low-Mr organic ligands was investigated by analyzing the xylem sap for organic and amino acids. We could not detect the presence of aconitate, citrate, fumarate, pyruvate, or succinate anions in the xylem sap of either Thlaspi species (Table II). The predominant organic acids in the xylem sap of both Thlaspi species were acetate and malate. Acetate was the only organic-acid anion that showed an increase in response to elevated Zn exposure. When the Zn level in the growth solution was increased from 1 to 50 μm, xylem acetate levels increased approximately 3-fold in T. arvense and almost 5-fold in T. caerulescens.

Analysis of the xylem sap amino acid content revealed few significant differences between T. arvense and T. caerulescens (Table II). The major difference was in Glu, which was 3- to 4.5-fold greater in T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense. However, the concentration of Glu did not increase in the xylem sap of plants grown in the high-Zn solution. His was not detected in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens.

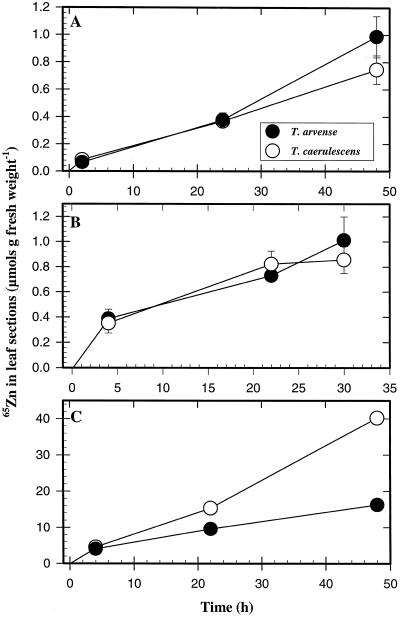

Uptake of 65Zn2+ into Leaf Tissues

After an initial rapid phase the time course of Zn accumulation into leaf sections from the uptake solutions containing from 10 to 1000 μm 65Zn2+ was approximately linear for up to 48 h. We speculate that the initial rapid phase involves Zn movement into the apoplast through the residual cuticle and cut edges of the leaf sections (Fig. 3). At the lower Zn concentrations (10 and 100 μm), there were no detectable differences in leaf Zn accumulation between the two Thlaspi species (Fig. 3, A and B). However, at the higher Zn concentration (1000 μm), which is probably more representative of the Zn concentration in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens, approximately 2.5-fold more Zn was accumulated in T. caerulescens leaf sections by the end of the 48-h uptake period (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Time course of 65Zn accumulation in leaf sections of the two Thlaspi species. Leaves of T. arvense and T. caerulescens seedlings were cut into 10- to 20-mm2 sections and immersed in an uptake solution containing 2 mm Mes-Tris buffer, pH 6.0, 0.5 mm CaCl2 and 10 μm (A), 100 μm (B), or 1000 μm (C) 65ZnCl2. After exposures for up to 48 h, the radioactive uptake solution was replaced with a solution consisting of 5 mm Mes-Tris, pH 6.0, 5 mm CaCl2, and 100 μm ZnCl2 and allowed to desorb for 15 min. Leaf sections were then harvested, blotted, and weighed, and the gamma activity was measured. Data points represent means ± se of four replicates.

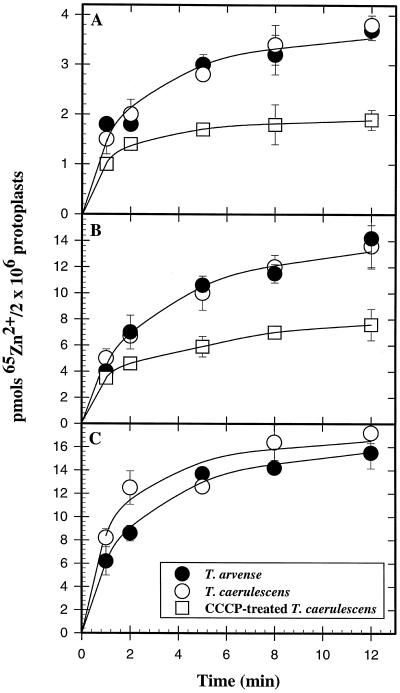

Leaf Zn transport was also studied at the cellular level using protoplasts isolated from leaves of the two Thlaspi species. The time dependence of 65Zn uptake was studied in uptake solutions containing 10, 100, and 1000 μm 65Zn2+ (Fig. 4). Zn uptake from a solution containing 10 or 100 μm 65Zn2+ was similar in protoplasts isolated from T. arvense and T. caerulescens leaves. At a high Zn2+ concentration (1000 μm), there was a small tendency for higher Zn uptake in T. caerulescens protoplasts, but this difference was considerably less than that obtained with leaf sections.

Figure 4.

Time course of 65Zn accumulation in protoplasts isolated from the two Thlaspi species. Protoplasts isolated from T. arvense and T. caerulescens leaves were suspended in an uptake buffer containing 10 μm (A), 100 μm (B), or 1000 μm (C) 65ZnCl2. At different time intervals up to 12 min, an aliquot of the uptake suspension was collected and placed on top of a discontinuous gradient consisting of 50 μL of 10% (v/v) HClO4 on top of 400 μL of silicon oil, and the protoplasts were pelleted by centrifugation. The tube was then frozen in liquid N2 and the tip containing the pellet was cut and placed in a vial, and the gamma activity was measured. For the experiments with CCCP, protoplasts were exposed to 10 μm CCCP for 30 min before the uptake experiment.

Exposure of protoplasts to the protonophore and metabolic inhibitor CCCP (10 μm) elicited a large (>50%) inhibition of 65Zn2+ uptake into T. caerulescens protoplasts (Fig. 4, A and B). Uptake of 65Zn2+ into liquid-N2-ruptured protoplasts saturated rapidly (in less than 1 min) and very little 65Zn subsequently accumulated. At the end of a 12-min uptake period, approximately 2.2-fold more 65Zn2+ had accumulated in intact compared with ruptured protoplasts (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Time course of 65Zn uptake in intact and ruptured T. arvense protoplasts. Protoplasts were ruptured by freezing in liquid N2. The uptake solution contained 10 μm 65Zn2+. At different time intervals up to 12 min, an aliquot of the uptake suspension was removed and placed on top of a discontinuous gradient consisting of 50 μL of 10% (v/v) HClO4 on top of 400 μL of silicon oil, and the protoplasts were pelleted by centrifugation. The tube was then frozen in liquid N2 and the tip containing the pellet was cut and placed in a vial, and the gamma activity was measured.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of Zn hyperaccumulation in leaf cells of T. caerulescens is not clearly understood. It is likely that a number of steps are involved in the Zn2+ movement from the rhizosphere to the shoots, including (a) Zn2+ influx across the root cell plasma membrane; (b) radial Zn movement across the root; (c) loading into xylem vessels in the stelar region of the root; (d) translocation from the root to the shoot; (e) absorption of Zn from the xylem into leaf cells; and (f) transport across the leaf cell tonoplast. Additionally, because Zn tolerance plays a major role in hyperaccumulation, Zn detoxification involving a number of different organic ligands most likely plays a part in the overall response.

We have previously shown that despite a small Zn2+ influx into root cells, more radioactive Zn was accumulated in T. arvense roots than in T. caerulescens (Lasat et al., 1996). However, after a 96-h period, 65Zn translocation to the shoot was 10- to 20-fold higher in T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense. These findings suggest that Zn compartmentation is fundamentally different in the roots of the two Thlaspi species, and that certain processes associated with Zn loading into the xylem are also stimulated in T. caerulescens.

We conducted a radiotracer efflux (compartmental) analysis to investigate indirectly 65Zn compartmentation in the cytoplasm and vacuole of the two Thlaspi species. We have used this approach previously in several different studies to investigate the root compartmentation of a number of monovalent and divalent cations (Kochian and Lucas, 1982; Hart et al., 1992; DiTomaso et al., 1993; Lasat et al., 1997) and are very familiar with its limitations. This technique was developed to study ion compartmentation in single giant algal cells, in which the ion content of the individual compartments (vacuole, cytoplasm, and cell wall) can be measured directly (MacRobbie, 1971). Several researchers have questioned the extension of compartmental analysis to complex, multicellular higher plant organs such as roots. For example, it has been argued that radiolabeled ions may be slowly released from the cell wall-binding sites (Spanswick and Williams, 1965; Jorgenson, 1966), chemically bound within the cytoplasm (Robinson and Jackson, 1986), or compartmentalized in other organelles such as plastids (Cheeseman, 1986). However, in compartmental studies with oat coleoptiles (Pierce and Higinbotham, 1970) and carrot root tissues (Cram, 1968), the authors provided strong arguments and analyses that allowed them to validate this technique for the application of the three-compartment-in-series model to plant organs such as roots and leaves. For a detailed examination of the application of this technique for ion compartmentation in roots, see Kochian and Lucas (1982).

The application of radiotracer efflux analysis to roots only allows for an indirect and semiquantitative estimate of ion fluxes and loading in the vacuole, cytoplasm, and cell wall. Unfortunately, no other experimental method is currently available to investigate ion compartmentation in a semiquantitative manner. Moreover, this technique has been used to provide valuable information on the efflux and compartmentation of several ions such as K+ (Kochian and Lucas, 1982), Na+ (Pierce and Higinbotham, 1970), NH4+ (Macklon et al., 1990), Cd2+ (Rauser, 1987), Cu2+ (Thornton, 1991), Zn2+ (Santa Maria and Cogliatti, 1988), and Co2+ (Macklon and Sim, 1987).

At the end of the 24-h 65Zn-loading period, 65Zn2+ had accumulated to comparable levels in roots of T. arvense and T. caerulescens (Figs. 1A and 2A). The Zn-compartmentation data summarized in Table I suggest that similar amounts of Zn were stored in the root apoplast of the two Thlaspi species, which argues against sequestration of Zn in the root cell wall of T. arvense as a mechanism of Zn tolerance, as suggested by Peterson (1969) for Agrostis tenuis. Zn levels were also similar in the T. arvense and T. caerulescens root cell cytoplasm (Fig. 1B; Table I); however, there were significant differences in the degree of Zn vacuolar accumulation and the rate of Zn efflux back out of the vacuole. As shown in Table I, almost 2.5-fold more Zn was stored in the vacuoles of T. arvense roots, and Zn efflux out of the vacuole was about 2-fold faster in T. caerulescens. These findings suggest that Zn is sequestered in the root vacuole of T. arvense, possibly being made unavailable for loading into the xylem. Because vacuolar efflux was slower in T. arvense, the difference in root residual Zn between T. arvense and T. caerulescens should increase after longer efflux periods. In support of this, after a 46-h period, approximately 6-fold more 65Zn remained in the root of T. arvense compared with T. caerulescens (Fig. 2A).

Although Zn flux into T. caerulescens roots was significantly greater (Lasat et al., 1996), cytoplasmic Zn content was similar in the two Thlaspi species (Fig. 1A), presumably because of a greater Zn throughput across the T. caerulescens root and into the xylem. This was supported by a 5-fold increase in Zn concentration in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense. From these data we cannot determine whether Zn transport involved in the loading of Zn from xylem parenchyma into xylem vessels was stimulated in T. caerulescens. It is possible that the elevated Zn in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens was attributable solely to the enhanced Zn influx into the root and to altered root compartmentation, which should facilitate radial Zn movement across the root to the xylem.

An important aspect of Zn hyperaccumulation in T. caerulescens might be the production of low-Mr organic ligands that can complex Zn2+ in the plant cell cytoplasm, rendering it nontoxic. It is also likely that organic ligands help facilitate the long-distance transport of Zn in the xylem (White et al., 1981) and might be instrumental in helping sequester Zn in the leaf cell vacuole. To investigate the possible role of organic ligands in long-distance Zn transport in the xylem and in Zn reabsorption in leaves, we analyzed the composition of xylem sap isolated from both Thlaspi species in plants grown at low and high Zn levels. Our results showed a significant increase in the level of acetic acid in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense. However, because acetate is a weak ligand for Zn2+ (Smith and Martell, 1989), this increase may not directly facilitate Zn translocation from root to shoot, but, rather, might be involved in the maintenance of cation-anion balance in response to the high level of Zn2+ transported in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens. In support of this, the addition of acetate to the uptake medium at concentrations as high as 4 mm did not stimulate 65Zn2+ accumulation in leaf sections of either Thlaspi species (results not shown).

We also investigated the possibility that amino acids are involved in long-distance transport of Zn, because His production and accumulation in the xylem was shown to be involved in Ni hyperaccumulation in shoots of Alyssum (Krämer et al., 1996). In the present study, however, His was not detected in the xylem sap of T. caerulescens, but was found in moderate levels in the xylem of T. arvense. Glu was found to be the most abundant amino acid in the xylem sap of both species of Thlaspi, but Glu concentrations were 3- to 5-fold higher in the T. caerulescens xylem sap. However, the Glu concentration of the xylem sap did not increase in response to increasing Zn concentrations in the xylem, and addition of Glu at concentrations as high as 500 μm did not stimulate 65Zn2+ uptake in leaf sections of either Thlaspi species (results not shown), suggesting that Glu does not facilitate reabsorption of xylem-borne Zn into leaf cells.

Because one of the major storage sites for Zn is the leaf vacuole (Vázquez et al., 1994), we investigated the possibility that Zn influx across the leaf cell plasma membrane was stimulated in T. caerulescens. We found that at lower Zn concentrations (10 and 100 μm), there were no differences in 65Zn uptake into leaf sections or protoplasts isolated from the two Thlaspi species. However, when the Zn concentration was increased to 1 mm, 65Zn accumulation was significantly stimulated in leaves of T. caerulescens. This finding is interesting, for it suggests that Zn transport is stimulated at both the root cell and leaf cell plasma membrane in the hyperaccumulator species. If this is the case, then the Zn transporter has different kinetic properties in roots versus shoots, because stimulated root Zn2+ influx was observed in T. caerulescens at external Zn2+ concentrations as low as 1 μm (Lasat et al., 1996), whereas in leaves it was observed at much higher Zn2+ concentrations (1 mm). It should also be noted that enhanced Zn transport into leaf cells could reflect a stimulated transport system operating in the leaf cell tonoplast, which could effectively move cytoplasmic Zn into the vacuole.

To avoid the confounding effect of the cuticle and the cell wall, accumulation of 65Zn2+ in leaf tissues was also investigated using protoplasts isolated from leaves of the two Thlaspi species. The uptake curves were biphasic, with an initial rapid linear component followed by a slower one. We previously found similar biphasic, time-dependent kinetics for the uptake of another divalent cation, methyl viologen, in maize protoplasts (Hart et al., 1993). Those findings were consistent with the initial, rapid phase being a combination of true uptake and considerable cation binding to the negatively charged sites on the outer face of the plasma membrane and the second, slower phase being influx across the plasma membrane.

To determine whether this interpretation applied to the uptake curves shown in Figure 4, we conducted uptake studies in the presence of CCCP, an anionic protonophore and metabolic inhibitor (Heyter and Prichard, 1962). Exposure to CCCP has also been shown to dramatically depolarize the electrical potential across the plasma membrane of plant cells (DiTomaso et al., 1992), which could inhibit the electrical driving force for divalent cation uptake. Our data (Fig. 4, A and B) indicate that the CCCP treatment strongly inhibited 65Zn2+ transport into protoplasts, indicating that we were measuring primarily true transmembrane Zn2+ transport into Thlaspi protoplasts. 65Zn2+ binding to the plasma membrane was also investigated in liquid-N2-ruptured protoplasts (Fig. 5), and indicated that Zn binding to the plasma membrane was rapid, saturating within 1 to 2 min, whereas Zn accumulation into intact protoplasts continued for at least 10 min.

It is interesting to note that although we observed a significant increase in Zn accumulation in cells from leaf segments of T. caerulescens compared with T. arvense (at high exogenous Zn concentrations), these Zn-transport differences disappeared in isolated leaf protoplasts. This suggests that either an intact leaf is required to express the enhanced Zn uptake in T. caerulescens, or that the artificial conditions associated with protoplasts are such that they do not accurately reflect the physiology of leaf cells in an intact leaf. An estimate of “true Zn influx” of 6 pmol Zn 106 protoplasts−1 h−1 was obtained by subtracting the amount of 65Zn2+ binding in ruptured protoplasts from the Zn accumulation measured in intact protoplasts. Our calculations indicate that this rate was at least 2 orders of magnitude lower than the rate of Zn uptake into intact leaf cells (leaf sections). Therefore, under the altered physiological conditions the identification of Zn-transport differences in protoplasts isolated from the two Thlaspi species might be compromised and should be viewed with some caution.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that altered tonoplast Zn transport in the root and stimulated Zn uptake in the leaf play a role in the dramatic Zn hyperaccumulation expressed in T. caerulescens.

Abbreviations:

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone

- FDA

fluorescein diacetate

LITERATURE CITED

- Baker AJM, Brooks RR. Terrestrial higher plants which hyperaccumulate metallic elements: a review of their distribution, ecology and phytochemistry. Biorecovery. 1989;1:81–126. [Google Scholar]

- Baker AJM, McGrath SP, Reeves RD, Smith JAC (1998) Metal hyperaccumulator plants: a review of the ecology and physiology of a biological resource for phytoremediation of metal-polluted soils. In N Terry, GS Bañuelos, eds, Phytoremediation. Ann Arbor Press, Ann Arbor, MI (in press)

- Baker AJM, Reeves RD, Hajar ASM. Heavy metal accumulation and tolerance in British populations of the metallophyte Thlaspi caerulescens J. & C. Presl (Brassicaceae) New Phytol. 1994;127:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Chaney RL, Angle JS, Baker AJM. Phytoremediation potential of Thlaspi caerulescens and bladder campion for zinc- and cadmium-contaminated soil. J Environ Qual. 1994;23:1151–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Chaney RL, Angle JS, Baker AJM. Zinc and cadmium uptake by hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens and metal tolerant Silene vulgaris grown on sludge-amended soils. Environ Sci Technol. 1995a;29:1581–1585. doi: 10.1021/es00006a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Chaney RL, Angle JS, Baker AJM. Zinc and cadmium uptake by hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens grown in nutrient solution. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1995b;59:125–133. doi: 10.1021/es00006a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney RL. Zinc phytotoxicity. In: Robson AD, editor. Zinc in Soil and Plants. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman JM. Compartmental efflux analysis: an evaluation of the technique and its limitations. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:1006–1011. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.4.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram WJ. Compartmentation and exchange of chloride in carrot root tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;163:339–353. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(68)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiTomaso JM, Hart JJ, Kochian LV. Compartmentation analysis as a means of estimating the rate of vacuolar accumulation and translocation to shoots. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:467–472. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiTomaso JM, Hart JJ, Linscott DL, Kochian LV. Effect of inorganic cations and metabolic inhibitors on putrescine transport in roots of intact maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:508–514. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbs SD, Lasat MM, Brady DJ, Cornish J, Gordon R, Kochian LV. Phytoextraction of cadmium and zinc from a contaminated site. J Environ Qual. 1997;26:1424–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Hart JJ, DiTomaso JM, Kochian LV. Characterization of paraquat transport in protoplasts from maize (Zea mays L.) suspension cells. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:963–969. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JJ, DiTomaso JM, Linscott DL, Kochian LV. Characterization of the transport and cellular compartmentation of paraquat in roots of intact maize seedlings. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1992;43:212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Heyter PG, Prichard WW. A new class of uncoupling agents: carbonyl cyanide phenyl hydrazones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1962;7:272–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(62)90189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson CK (1966) Symmetry and chemical bonding in copper-containing chromophores. In J Peisach, P Aisen, WE Blumberg, eds, The Biochemistry of Copper. Academic Press, New York, pp 1–14

- Kochian LV, Lucas WJ. Potassium transport in corn roots. I. Resolution of kinetics into a saturable and linear component. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:1723–1731. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.6.1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer U, Cotter-Howels JD, Charnock JM, Baker AJM, Smith JAC. Free histidine as a metal chelator in plants that accumulate nickel. Nature. 1996;379:635–638. [Google Scholar]

- Lasat MM, Baker AJM, Kochian LV. Physiological characterization of root Zn2+ absorption and translocation to shoots in Zn hyperaccumulator and nonaccumulator species of Thlaspi. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1715–1722. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasat MM, DiTomaso JM, Hart JJ, Kochian LV. Evidence for vacuolar sequestration of paraquat in roots of a paraquat-resistant Hordeum glaucum biotype. Physiol Plant. 1997;99:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Macklon AES, Ron MM, Sim A. Cortical cell fluxes of ammonium and nitrate in excised root segments of Allium cepa L: studies using 15N. J Exp Bot. 1990;41:359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Macklon AES, Sim A. Cellular cobalt fluxes in roots and transport to the shoots of wheat seedlings. J Exp Bot. 1987;38:1663–1677. [Google Scholar]

- MacRobbie EAC. Fluxes and compartmentation in plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1971;22:75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda Kumar PBA, Dushenkov V, Motto H, Raskin I. Phytoextraction: the use of plants to remove heavy metals from soils. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29:1232–1238. doi: 10.1021/es00005a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PJ. The distribution of zinc-65 in Agrostis tenuis Sibth. and A. stolonifera L. tissues. J Exp Bot. 1969;20:863–875. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce WS, Higinbotham N. Compartments and fluxes of K+, Na+, and Cl− in Avena coleoptile cells. Plant Physiol. 1970;46:666–673. doi: 10.1104/pp.46.5.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauser WE. Compartmental efflux analysis and removal of extracellular cadmium from roots. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:62–65. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves RD, Brooks RR. European species of Thlaspi L. (Cruciferae) as indicators of nickel and zinc. J Geochem Explor. 1983;18:275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NJ, Jackson PJ. ‘Metallothionein-like’ metal complexes in angiosperms: their structure and function. Physiol Plant. 1986;67:499–506. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Maria GE, Cogliatti DH. Bidirectional Zn-fluxes and compartmentation in wheat seedling roots. J Plant Physiol. 1988;132:312–315. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RM, Martell AE (1989) Critical Stability Constants, Vol 6, Suppl 2. Plenum Press, New York, pp 300–302

- Spanswick RM, Williams EJ. Ca fluxes and membrane potentials in Nitella translucens. J Exp Bot. 1965;16:463–473. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton B. Indirect compartmental analysis of copper in live ryegrass roots: comparison with model systems. J Exp Bot. 1991;42:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez MD, Poschenrieder C, Barceló J, Baker AJM, Hatton P, Cope GH. Compartmentation of zinc in roots and leaves of the zinc hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens J&C Presl. Bot Acta. 1994;107:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- White MC, Decker AM, Chaney RL. Metal complexation in xylem fluid. I. Chemical composition of tomato and soybean stem exudate. Plant Physiol. 1981;67:292–300. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]