Abstract

Among agents of selection that shape phenotypic traits in animals, humans can cause more rapid changes than many natural factors. Studies have focused on human selection of morphological traits, but little is known about human selection of behavioural traits. By monitoring elk (Cervus elaphus) with satellite telemetry, we tested whether individuals harvested by hunters adopted less favourable behaviours than elk that survived the hunting season. Among 45 2-year-old males, harvested elk showed bolder behaviour, including higher movement rate and increased use of open areas, compared with surviving elk that showed less conspicuous behaviour. Personality clearly drove this pattern, given that inter-individual differences in movement rate were present before the onset of the hunting season. Elk that were harvested further increased their movement rate when the probability of encountering hunters was high (close to roads, flatter terrain, during the weekend), while elk that survived decreased movements and showed avoidance of open areas. Among 77 females (2–19 y.o.), personality traits were less evident and likely confounded by learning because females decreased their movement rate with increasing age. As with males, hunters typically harvested females with bold behavioural traits. Among less-experienced elk (2–9 y.o.), females that moved faster were harvested, while elk that moved slower and avoided open areas survived. Interestingly, movement rate decreased as age increased in those females that survived, but not in those that were eventually harvested. The latter clearly showed lower plasticity and adaptability to the local environment. All females older than 9 y.o. moved more slowly, avoided open areas and survived. Selection on behavioural traits is an important but often-ignored consequence of human exploitation of wild animals. Human hunting could evoke exploitation-induced evolutionary change, which, in turn, might oppose adaptive responses to natural and sexual selection.

Keywords: contemporary evolution, anti-predator behaviour, shy–bold continuum, hunting, elk, Cervus elaphus, GPS telemetry

1. Introduction

Phenotypic traits of wild vertebrate and invertebrate populations are constantly shaped and reshaped by changes in the environment and by numerous agents of natural selection, including predators [1]. Among these countless factors, modern humans have emerged as a dominant evolutionary force [2]. Humans can cause more rapid phenotypic changes than many natural agents [3]. For several animal species, Darimont et al. [4] suggested that rates of phenotypic change driven by human harvest could outpace those driven by other selective forces. Human influence on phenotypes also might generate large and rapid changes in population and ecological dynamics, including those that affect population persistence [5,6].

By exploiting prey at high levels and targeting fundamentally different age- and size-classes than natural predators [7,8], humans can generate rapid phenotypic and genetic changes in both morphological and life-history traits in exploited prey [9]. However, while research has focused on human-mediated selection of morphological traits in wild populations (e.g. selection of large-antlered or large-horned ungulate males [10,11]), little is known about human-mediated selection of behavioural traits. Here we predict that prey, depending on individual personality traits, can adopt anti-predator behavioural strategies in response to human hunting pressure, and thus humans directly influence prey behavioural traits. The importance of behaviourally mediated effects of humans requires greater attention in the wild, as these effects have been shown only in domesticated animals [12,13].

We tested whether elk (Cervus elaphus) that were eventually killed by human hunters (hereinafter referred to as harvested) had less favourable behaviours than surviving elk in southwest Alberta, Canada. Elk is a good model species because of its high degree of behavioural plasticity in response to predators [14,15]. We deployed global positioning system (GPS) satellite-telemetry collars on 122 elk. GPS-radiotelemetry provides vast quantities of high-quality relocation data that allow for disentangling spatial anti-predator strategies adopted by large mammals [16]. We investigated among-individual differences in personality traits of males (n = 45, age: 2 y.o.) all facing the hunting season with the same experience level but no longer bonded with their mothers, which can influence anti-predator strategies of calves [17,18]. At the same time, we studied females (n = 77) from a range of experience levels (age: 2–19 y.o.) and thus different knowledge of the environment [19].

We predict that harvested elk have higher movement rates than those that survived, thus more likely to be detected by hunters [20], particularly in less-steep terrain that is more accessible to hunters, in open areas or close to roads where there is increased detectability, and during the weekend when human activity is higher. Therefore, our general prediction is that individuals choosing to increase movements as an anti-predator strategy to avoid hunters, especially when they are more visible, have a higher probability of being harvested than animals that take a ‘hiding’ strategy by decreasing movement rate as an anti-predator strategy. These patterns should be more evident in males, as we studied young males with low experience levels, whereas learning could confound personality traits in older females.

In our study design, we first assessed the movement strategies of harvested elk versus those that survived before and during the hunting season. If behavioural differences between elk represent personality differences versus learning, those differences should be already present before the onset of the hunting season. We then calculated which spatial behaviour patterns affected the probability of an elk being harvested.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study area

The study occurred within a montane ecosystem along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains in southwest Alberta, Canada. Some monitored elk moved to southeastern British Columbia and northwestern Montana during study (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1). This is a diverse landscape, from flat agriculturally developed grasslands to mixed conifer/hardwood forests and abrupt mountains.

Human activity was intense during the autumn hunting season, especially during weekends. Hunters access hunting areas using forestry roads and trails, searching at dawn and dusk until they detect prey, often using binoculars or spotting scopes. We deployed 43 trail cameras along roads and trails in the study area [21] to quantify human activity. Humans counted per day during weekends was 20.7 ± 5.7 (mean ± s.e.), and significantly lower (12.4 ± 3.3 humans per day) during weekdays (paired sample t-test: n = 43, t = 3.112, p = 0.003) [21].

The elk rifle hunting season was from early September until the end of November. Wolf (Canis lupus) cougar (Puma concolor) and grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) are the main natural predators in the area [21].

(b). Elk data

Male (n = 45) and female (n = 77) elk were captured (animal care protocol no. 536-1003 AR University of Alberta) during the winters of 2007–2011 using helicopter net-gunning. Males were fitted with Lotek ARGOS GPS-radiotelemetry collars, whereas females were fitted with Lotek GPS-4400 radiotelemetry collars (Lotek wireless Inc., Ontario, Canada). All collars were programmed with a 2-h relocation schedule. Satellite transmitted data of males were received weekly via email, whereas data of females were remotely downloaded in the field. A total of 635 700 GPS relocations collected from January 2007 to December 2011 were used in this study. A vestibular canine was taken using dental lifters during the capture to assess age through cementum analysis (Matson's Laboratory, MT, USA). All males were aged 1.5 y.o. during the winter capture, and consequently they faced the following hunting season at the age of 2.5 y.o. (greater than equal to three-point antlers). Age of females ranged from 2 to 19 y.o. By the last day of the hunting season, 97 elk were still alive and 25 had been harvested (table 1; see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2 for details on monitoring period). Age of females that were harvested ranged from 2 to 9 y.o. The majority (93%) of hunting mortalities occurred between early September and early November.

Table 1.

Elk monitored using GPS radio telemetry in southwest Alberta and southeast British Columbia, Canada and northwest Montana, USA from 2007 to 2011. Sample size was split according to sex, individual movement strategy (migratory, disperser or resident) and individual fate during hunting season.

| males n = 45 |

females n = 77 |

grand total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| migratory | disperser | resident | total | migratory | disperser | resident | total | ||

| harvested | 11 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 25 |

| survived | 22 | 7 | 1 | 30 | 59 | 1 | 7 | 67 | 97 |

| total | 33 | 10 | 2 | 45 | 67 | 1 | 9 | 77 | 122 |

(c). Ecological factors affecting elk mobility

We calculated step length (i.e. distance between 2 h telemetry relocations, in metre) as a proxy of elk mobility [22] using ARCMAP v. 9.2 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA) with the Hawth's Tools extension (http://www.spatialecology.com/htools/). We report in table 2 the complete list of ecological factors that have been predicted to affect elk mobility (i.e. step length) based on previous studies on ungulates [19,20,22–31] and our own predictions (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1 for further details on GIS data). To distinguish migration from other movement behaviours, we used a single measurement, the net-squared displacement (NSD) that measures the straight line distances between the starting location and the subsequent locations for the movement path of a given individual. On the basis of shape of NSD patterns, we split the monitored sample into disperser, migratory and resident elk [32] (see table 1 and electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Dawn and dusk periods were assessed each month as the 4 h period around twilight start and twilight end (sun 6° below horizon) for which we obtained the daily occurrence using the sunrise/sunset calculator for the geographical centre of the study site (http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/eng/services/hia/sunrise-sunset.html).

Table 2.

Candidate ecological factors that influence elk mobility (step length) before and during the hunting season.

| group of factors included in model selection | factors | variables associated with elk step length | predicted link with individual movement rate (step length) | supporting examplesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| individual behaviour | hunting season fate | survived or harvested | higher movement rates are expected in elk that are eventually shot by hunters (through increased encounters with humans) | [20] |

| Julian date | Julian date | elk mobility could flexibly fluctuate through time (Julian date), e.g. depending on movement behaviour, period of the year (rut) and hunting pressure | [23–25] | |

| movement behaviour | migratory, disperser, resident | higher movement rates are expected in dispersers or young migratory individuals owing to exploratory behaviour within unknown grounds | [26] | |

| individual experience (age) | age | age | home ranges and, arguably, movement rates decrease with age (as a result of increased experience and/or knowledge of the habitat) | [19] |

| environment | day period | night, dawn, day, dusk | higher movement rates are expected at dawn and dusk as a result of crepuscular activity | [27] |

| terrain ruggednessb,c | terrain ruggedness r | lower movement rates are expected as higher energy expenditure for locomotion is required due terrain ruggedness, and, consequently, elevation and snow cover. | [28] | |

| open areas (anti-predator behaviour) | elk step length recorded outside or inside open areas (un-forested) | higher movement rates are expected within open areas because of higher perceived risk | [29] | |

| open areas (foraging behaviour) | lower movement rates are expected if animals forage in open habitat | [22] | ||

| humans | land use (human disturbance on a large spatial scale) | national park, private land, public land | different movement rates are expected within national park, private and public land, but the direction of such an effect is still unclear | [20,30] |

| distance from gravel roadsc (human disturbance on a small spatial scale) | distance from the nearest gravel road dgrv | higher movement rates are expected close to roads | [31] | |

| week period (human disturbance on a temporal scale) | weekday or Sat.–Sun. | higher movement rates are expected when human disturbance increases (i.e. during the weekend) | [31] | |

| two-way interactions | different response to humans between elk that are harvested or survive during the hunting season | two-way interactions | elk that are harvested are expected to move faster (higher detectability) when and where hunter activity is higher (i.e. flatter terrain, open areas, close to roads, during weekends) | none |

aIn ungulates.

bCollinear with elevation and snow cover in winter time.

cComputed for the telemetry relocation prior to the step length.

We modelled variation in step length (natural log-transformed, hereinafter referred to as step length) using generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs) [33] in R v. 2.14.1 [34], with individual elk fitted as a random intercept [35]. Following Burnham et al. [36], we constructed four sets of a priori GAMMs (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2–S5).

The first two sets of models (one for each sex, electronic supplementary material, table S2 and S4) were built to predict the variation of step length from January, i.e. after the end of the hunting season, through the next autumn hunting season. This approach allowed us to verify whether (i) harvested and survived elk had different movement rates before the onset of the hunting season, and (ii) elk were sensitized (e.g. suddenly changed their movement rate) at the onset of the hunting season. Using GAMMs allowed us to flexibly model step length through time (Julian date) by fitting smoothing splines [33]. We also fit smoothing splines for elk that survived and harvested elk separately (Julian date by hunting season fate), and smoothing splines to allow for a nonlinear effect of age on step length of females (see the electronic supplementary material, table S4).

We built two more sets of models (one for each sex, electronic supplementary material, tables S3 and S5) to predict variation in step length during the hunting season. We included four two-way interactions between hunting season fate (survived, harvested) and terrain ruggedness r, open areas (outside, inside), distance from gravel roads dgrv and week period (weekday, Sat.–Sun.) to verify the different individual responses to human presence between elk that survived or were harvested. To test whether experience might affect the response of females to the presence of hunters, we fit smoothing splines for the effect of age on step length for survived and harvested elk separately.

The use of AIC to select the best model could be problematic when using mixed models, given that AIC penalizes models according to the number of predictor variables [37], which is not clear because of the random effect. We thus examined our four sets of GAMMs using the deviance information criterion [38,39]. Parameters were estimated for top-ranked models.

We verified whether harvested and survived elk in our final top-ranked models were spatially autocorrelated with each other. Heterogeneity in hunting pressure could lead to spatial segregation between survived and harvested elk. Autocorrelated step length could also be expected among individuals using the same areas. We did not find any pattern in the spatial distribution of elk that survived and were harvested (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1), nor in the distribution of residuals of top-ranked GAMMs plotted versus their spatial coordinates (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3 [40]). Inspections of variograms allowed us to exclude spatial autocorrelation of residuals in top-ranked models (Moran's I-test: p ≥ 0.353 in all cases; see electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

(d). Behaviours affecting probability of being harvested during hunting season

We investigated behavioural choices that affected the probability of an elk being harvested during the hunting season. For these analyses, we excluded those animals (n = 4 males, n = 5 females) that were partially located within National Parks during the hunting season (where no hunting is allowed) or within management units where the hunting of elk males greater than equal to three points was not allowed. For these animals, the probability of mortality was negatively affected by local harvest management restrictions. For all other animals, we fit generalized linear models (GLMs) in R v. 2.14.1 [34], with binomial error distribution with hunting season fate (survived = 0, harvested = 1) as a response variable. Following Burnham et al. [36], we constructed two sets of a priori mixed models (seven for males, 15 for females) using the following explanatory variables: mean distance from gravel roads (dgrv), mean terrain ruggedness (r), mean step length, elk age during the hunting season (for female models only) and selection ratios for open areas (woa). To calculate selection ratios, we generated 5000 random points within each hunting season 95 per cent kernel elk home range. We calculated selection ratios for open areas (woa) as the frequency of used locations (within open areas) divided by the frequency of random locations within open areas [41]. For each sex, parameter estimates were reported for the top-ranked model identified by minimum AIC model ranking and weighting [42].

3. Results

(a). Ecological factors affecting male mobility

Selection and parameter estimates of the best GAMM predicting step length of males from January through the hunting season are reported in the electronic supplementary material, table S2. Males that were harvested moved faster (mean step length recorded every 2 h ± s.e.: 328.7 ± 3.1 m) than elk that survived (292.5 ± 2.0 m) the hunting season. Predictions of the top-ranked GAMM for the variation of step length of harvested versus survived elk are reported in figure 1a. Elk that were harvested during the hunting season moved faster before the onset of the hunting season than elk that survived (figure 1a and electronic supplementary material, table S2). Elk showed pronounced crepuscular activity while moving faster at dawn (474.2 ± 4.9 m) and dusk (378.1 ± 4.6 m) than during the day (273.6 ± 2.5 m) and night (175.4 ± 2.4 m). Males moved faster in areas of low terrain ruggedness and open areas (323.4 ± 2.4 m) than outside of them (287.7 ± 2.3 m). Males also moved faster when closer to gravel roads and during Sat.–Sun. (309.8 ± 3.2 m) compared with weekdays (302.3 ± 2.0 m). Movement behaviour (migratory, resident, disperser) and land use were factors retained in the best model.

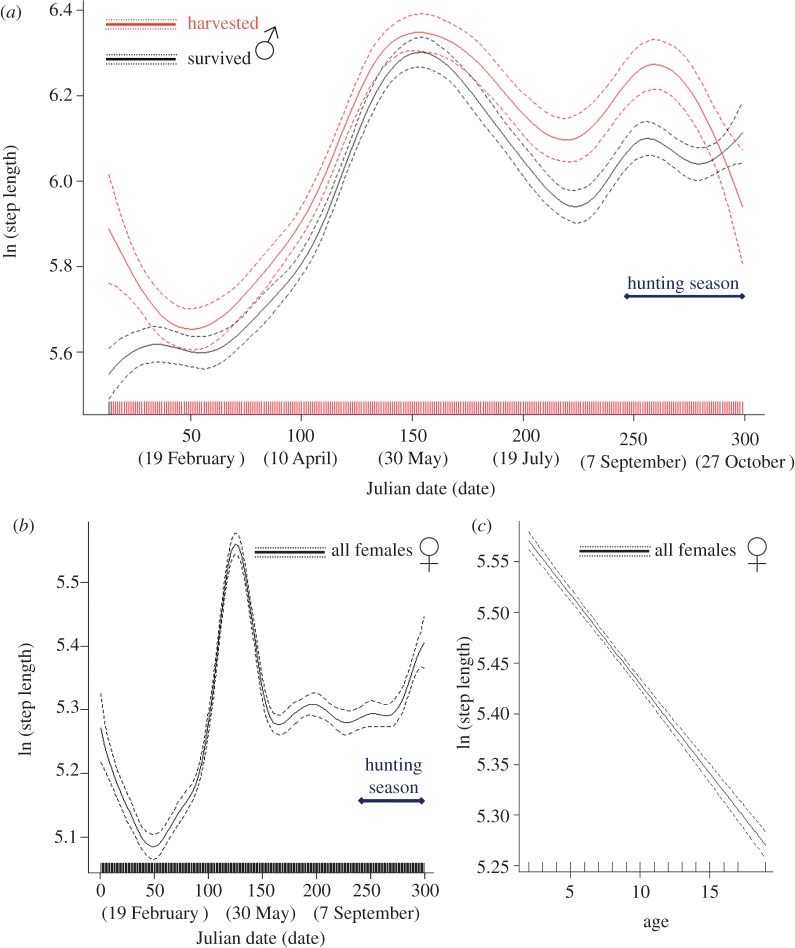

Figure 1.

Predicted variation of step length over the time (from January through the hunting season) in male elk that survived or were harvested during the hunting season (a), in female elk irrespective of their hunting season fate (b), and estimated smoother predicting the effect of age on the variation of step length in female elk (c). Smoothed predicted values and approximate point-wise 95% CIs were calculated by adding the intercept value to the contribution of both fixed and random effects in GAMMs.

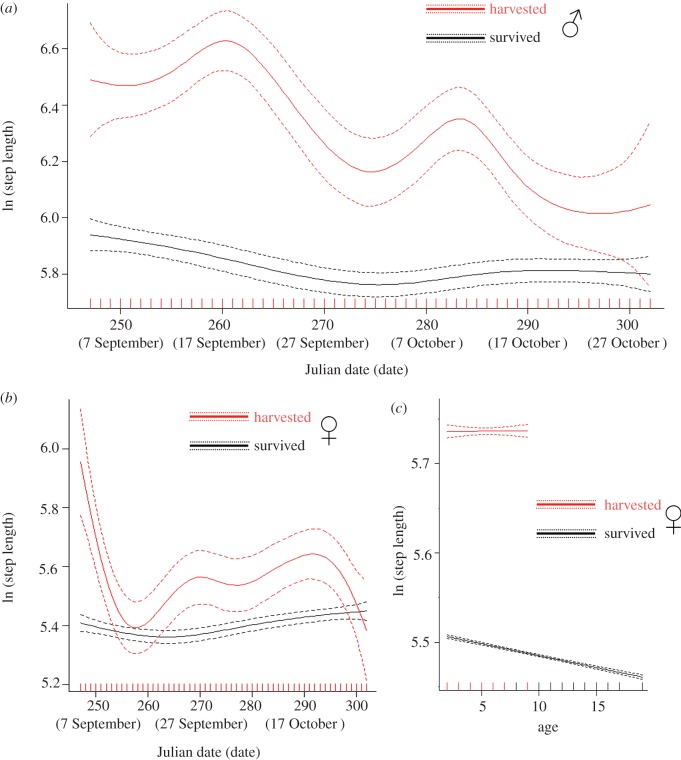

Selection and parameter estimates of the best GAMM predicting step length of males specifically during the hunting season are reported in the electronic supplementary material, table S3 and table 3. Predictions of the top-ranked GAMM for variation in step length of harvested elk versus those that survived are reported in figure 2a. Harvested males always moved faster (321.7 ± 9.9 m) than elk that survived (269.4 ± 4.4 m) the hunting season (table 3 and figure 2a). In general, variation of step length in males depending on environmental and human factors (e.g. faster movements at dawn and dusk, in flatter terrain, within open areas and closer to roads) recorded during the hunting season (table 3) were similar to those recorded throughout the year. The two-way interactions between hunting season fate and environmental factors were retained by the top-ranked model (table 3). Elk that were harvested moved faster than elk that survived as terrain ruggedness decreased (i.e. flatter terrain) and when closer to roads (table 3). When located within 1 km from the closest road, harvested elk walked 58 m every 2 h more than those than survived (harvested: 333.5 ± 15.6 m; survived 275.9 ± 6.5 m). We also found a strong interaction between hunting season fate and week period in affecting elk step length (table 3). Elk that were harvested increased movement during weekends (weekday: 310.2 ± 11.2 m; Sat.–Sun. 350.0 ± 20.4 m), whereas survived elk did not (weekday: 270.7 ± 5.1 m; Sat.–Sun. 266.0 ± 8.4 m).

Table 3.

Coefficients (β) and standard errors (s.e.) estimated by the best general additive mixed model (GAMM) predicting step length (ln-transformed) of male elk (n = 45) in southwest Alberta, southeast British Columbia and northwest Montana during the hunting season.

| β | s.e. | |

|---|---|---|

| intercept | 6.464 | 0.390 |

| hunting season fate (harvested) | 2.189 | 1.220 |

| movement behaviour (migratory) | 0.095 | 0.086 |

| movement behaviour (resident) | 0.153 | 0.164 |

| day period (day) | −0.834 | 0.041 |

| day period (dusk) | −0.434 | 0.043 |

| day period (night) | −1.098 | 0.038 |

| terrain ruggedness r | −0.013 | 0.002 |

| open areas (inside) | 0.115 | 0.036 |

| land use (private land) | 0.184 | 0.086 |

| land use (public land) | 0.033 | 0.085 |

| log-distance from gravel roads dgrv | −0.043 | 0.023 |

| week period (Sat.–Sun.) | −0.055 | 0.033 |

| hunting season fate (harvested) × r | −0.005 | 0.003 |

| hunting season fate (harvested) × open areas (inside) | 0.018 | 0.076 |

| hunting season fate (harvested) × dgrv | −0.056 | 0.043 |

| hunting season fate (harvested) × week period (Sat.–Sun.) | 0.179 | 0.070 |

Figure 2.

Predicted variation of step length in male (a) and female elk (b) that survived or were harvested during the hunting season, and estimated smoothers for the effect of age on step length in female elk depending on hunting season fate (c). Smoothed predicted values and approximate point-wise 95% CIs were calculated by adding the intercept value to the contribution of both fixed and random effects in GAMMs.

(b). Ecological factors affecting female mobility

Selection and parameter estimates of the best GAMM predicting step length of females from January through the hunting season are reported in the electronic supplementary material, table S4. Hunting season fate was not retained in the top-ranked model. Females moved faster in spring and decreased their movement rate in summer (figure 1b). Inter-individual variability in step length in females was higher in summer and during hunting season whether compared with earlier periods of the year (figure 1b). Younger females moved faster than older ones (figure 1c). Females showed pronounced crepuscular activity moving faster at dawn (389.2 ± 2.4 m) and dusk (309.8 ± 2.3 m) than during the day (244.3 ± 1.2 m) and night (160.9 ± 1.3 m). Females moved faster in low terrain ruggedness and open areas (281.7 ± 1.2 m) than outside of them (234.6 ± 1.2 m), and they moved faster when closer to gravel roads and during Sat.–Sun. (265.8 ± 1.6 m) compared with weekdays (256.3 ± 1.0 m). Movement behaviour (migratory, resident, disperser) and land use were factors retained in the best model.

Selection and parameter estimates of the best GAMM predicting step length of females specifically during the hunting season are reported in the electronic supplementary material, table S5. Hunting season fate was retained in the best model. Predictions for the variation of step length of harvested versus survived elk are reported in figure 2b. Although females that were harvested sharply decreased their movement rate at the onset of the hunting season, they moved faster (304.2 ± 8.4 m) than females that survived (242.0 ± 2.2 m) throughout the hunting season (see the electronic supplementary material, table S5 and figure 2b). Step length recorded during the hunting season decreased as age increased in females that survived (figure 2c), while this was not true for females that were harvested (figure 2c). Females that were harvested (age less or than equal to 9 y.o.) moved faster (304.1 ± 8.4 m) than females younger (245.5 ± 2.9 m) or older (236.7 ± 3.5 m) than 9 y.o. that survived the hunting season.

Two-way interactions were retained in the top-ranked model (see the electronic supplementary material, table S5) but without a clear effect in females, with the exception of distance from roads. Females that were harvested moved faster than survived elk closer to roads. When located within 1 km from the closest road, harvested females walked 55 m every 2 h more than survived elk (harvested: 317.0 ± 11.5 m; survived 262.4 ± 3.1 m).

(c). Behaviours affecting probability of being harvested

Selection and parameter estimates of the most parsimonious GLM predicting the probability of an elk being harvested are reported in table 4 ((a) males, (b) females). Males were more likely to be harvested if they selected open areas, increased their movement rate and used flatter terrain. Indeed, males that survived avoided open areas (woa = 0.65 ± 0.04) more than harvested ones (woa = 0.82 ± 0.07). Females were more likely to be harvested if they selected open areas and their movement rate increased. While harvested females selected open areas (woa = 1.13 ± 0.07), survived ones avoided them (woa = 0.87 ± 0.05). Younger females (effect of age) using areas closer to roads (effect of dgrv) had a higher chance of being shot by hunters.

Table 4.

Generalized linear models (GLMs) predicting the probability of a male (a) or a female (b) elk being shot during the hunting season. The top-ranked model (in bold) selected for each sex using Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to estimate parameters (reported below each panel). Wi are Akaike weights.

| AIC | ΔAIC | wi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) factors included in the model (males) | |||

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + ruggedness r | 11900.0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length | 11924.4 | 24.4 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + distance from gravel roads dgrv | 11926.0 | 26.0 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa | 11934.5 | 34.5 | 0 |

| ruggedness r | 12360.6 | 460.6 | 0 |

| step length | 12387.7 | 487.7 | 0 |

| distance from gravel roads dgrv | 12403.9 | 503.9 | 0 |

| parameter estimates for the top-ranked male model (β ± s.e.): intercept −2.520 ± 0.112, Woa 1.793 ± 0.088, step length 0.046 ± 0.015, r −0.011 ± 0.002 | |||

| (b) factors included in the model (females) | |||

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + distance from gravel roads dgrv + age | 20904.2 | 0 | 1.0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + ruggedness r + age | 21131.4 | 227.2 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + age | 21167.5 | 263.2 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + age | 21183.0 | 278.8 | 0 |

| distance from gravel roads dgrv + age | 22487.1 | 1582.8 | 0 |

| ruggedness r + age | 22506.5 | 1602.2 | 0 |

| age + step length | 22579.2 | 1675.0 | 0 |

| age | 22601.2 | 1697.0 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + distance from gravel roads dgrv | 23215.2 | 2310.9 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length + ruggedness r | 23315.0 | 2410.8 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa + step length | 23320.5 | 2416.3 | 0 |

| selection ratios for open areas Woa | 23359.0 | 2454.8 | 0 |

| distance from gravel roads dgrv | 24239.6 | 3335.4 | 0 |

| ruggedness r | 24258.9 | 3354.7 | 0 |

| step length | 24277.7 | 3373.5 | 0 |

| parameter estimates for the top-ranked female model (β ± s.e.): intercept 2.076 ± 0.078, Woa 1.670 ± 0.042, step length 0.044 ± 0.012, dgrv −0.00020 ± 0.00001, age −0.244 ± 0.006 | |||

4. Discussion

(a). ‘Shy hiders’ versus ‘bold runners’

We substantiated our main prediction that individuals choosing to move faster (i.e. a ‘running’ strategy, thus increasing detectability sensu Frair et al. [20]) as an anti-predator strategy to escape from hunters have a higher probability of being harvested than those animals that decrease movement as an anti-predator strategy (i.e. a ‘hiding’ strategy). Patterns were stronger in young inexperienced males facing their first hunting season compared with females. Males with higher movement rate and weaker avoidance of open areas were eventually harvested compared with shy individuals with less conspicuous behaviour that survived. Personality clearly drove this pattern, given that inter-individual differences in movement rate were already present before the onset of the hunting season. Males that were harvested responded to hunters by moving faster than elk that survived, especially during weekends, close to roads and in flatter terrain. Flatter terrain is generally more accessible to hunters, while using sloped terrain gives an ungulate a better vantage point from which to watch for predators [43]. Thus, males that were harvested had adopted exactly the movement strategy that would increase their detectability where and when the probability of being spotted by a hunter was higher. We did not detect a significant increase in activity in males during the rut, which was likely confounded by the overlapping hunting season.

Personality traits were less evident in females, likely confounded by learning. Indeed, females adjusted their behaviour by decreasing movement rate with increasing age, perhaps as a result of increased experience and/or knowledge of the habitat [19]. However, our results showed that hunters harvested female elk based on behavioural traits. Among younger females (age 2–9 y.o.), females that moved faster and selected open areas during the hunting season were harvested, whereas females that survived moved more slowly and avoided open areas. Females that were harvested moved faster than those that survived when closer to roads, as recorded for males. Interestingly, movement rate decreased as age increased in survived females, but not among those that were eventually harvested. The latter clearly showed a lower plasticity and adaptability to the local environment. Older and more experienced females (10–19 y.o.) decreased detectability by moving slower, avoiding open areas, and consequently they all survived the hunting season.

Harvested elk could be defined as ‘runners’, while survived elk as ‘hiders.’ A noise, a car approaching or a person walking likely evoked opposite behavioural responses in eventually harvested and survived elk. Over the past few years, concepts of personality and temperament in wildlife have received increased attention [44]. In many vertebrates, including birds, fishes and rodents, individuals differ in aggressiveness, sociability, level of activity, reaction to novelty and fearfulness [45,46]. Such personality traits have been used to characterize behavioural types and gave rise to the concept of ‘bold’ and ‘shy’ individuals. The ‘shy–bold continuum’ is now recognized as a fundamental axis of behavioural variation in animals [44,47], and is associated with the response of an individual to risk-taking and novelty [48]. The cautious behaviour of elk that survived in our study (shy hiders) is certainly the end result of an extreme individual plasticity, resulting in the ability to adapt behaviour to more people on a weekend. An important question is whether the behavioural differences among individuals are highly repeatable (i.e. depending on personality traits) or if they are a consequence of recent experience? Hunters appear to create a ‘landscape of fear’ [49], but apparently individual elk respond to that stimulus very differently, significantly affecting their survival.

(b). Humans selecting behavioural traits: three-way community-level interactions

The occurrence of two contrasting alternative strategies (runners versus hiders) increases the probability that a behavioural trait will be selected by humans. Indeed, among the most ubiquitous recent impacts on vertebrate predator–prey dynamics are the global dissemination and explosive growth of humans in all but high Arctic landscapes [50]. As a consequence, the strength of the interaction that once involved native prey and native predators is now modulated by a complex, three-way community-level interaction involving people, predators and prey [51]. Hunting mortality is often substantially higher than natural mortality for game animals [52]. Selection of behavioural traits is an important but often-ignored the consequence of human exploitation of wild animals. Adaptation to exploitation might produce undesirable evolutionary change [52]. Such a change may not be undesirable if environmental conditions and selection pressures generate new evolutionary trajectories reflecting new conditions experienced by animals. For instance, if hunters are producing shyer elk that are harder to find, it may be undesirable for the hunters but not for the elk population. However, evolutionary change could become undesirable when previous selection pressures and the new ones are antagonistic, and the combination of both pressures is leading to a decrease in population viability [2–4]. Empirical studies showed how human harvest of ungulates may drive wolf–elk or wolf–caribou population trends [53–55], with special regards to ungulate populations subjected to multiple predators [56]. Human hunters might cause even more rapid changes if they are selecting elk anti-predator strategies differently than those selected by wolves. Increases in mobility could be the natural response of elk against their natural predator [57], but this strategy is clearly not favourable for avoiding human predation, as shown by our data.

Many species such as elk have been hunted by humans for centuries [58]; so human selection on prey is not new. Hunting pressure, though, might have been increased where human population has exploded in the recent past. However, the main difference between the pre-Columbian era and present day is technology. Modern hunters have high-powered rifles for hunting, and this favours different behaviours than when hunters were hunting with spears or with a bow. High-technology hunting is certainly introducing very different selection pressures, and this could explain why elk have not already evolved a consistent strategy to deal with modern hunting. Wildlife managers have typically placed primary emphasis on the demographic consequences of hunting, with little consideration of potential evolutionary effects [52]. If humans are indeed becoming the most powerful evolutionary force in the environment [2–4], wildlife managers might need to modify harvest regulations and policies to ensure that hunting is sustainable. Human-mediated evolutionary changes could reduce fitness [59–61] with the potential to affect future yield and population viability [52]. Species with a relatively high degree of individual behavioural plasticity (such as elk) are more likely to survive these new human selection pressures, but there could be direct trait-mediated consequences for the population as well as indirect consequences for other species that interact with elk (e.g. wolves). Furthermore, species with little behavioural plasticity might be in greater danger of extirpation or extinction.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC-CRD), Shell Canada Limited, Alberta Conservation Association (Grant Eligible Conservation Fund), Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Safari Club International, Alberta Parks and Parks Canada for funding and support. We thank three anonymous reviewers and the editors for invaluable comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Futuyma D. J. 2001. Evolutionary biology. Sunderland, MA: Sineauer Associates [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palumbi S. R. 2001. Evolution: humans as the world's greatest evolutionary force. Science 293, 1786–1790 10.1126/science.293.5536.1786 (doi:10.1126/science.293.5536.1786) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendry A. P., Farrugia T. J., Kinnison M. T. 2008. Human influences on rates of phenotypic change in wild animal populations. Mol. Ecol. 17, 20–29 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03428.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03428.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darimont C. T., Carlson S. M., Kinnison M. T., Paquet P. C., Reimchen T. E., Wilmers C. C. 2009. Human predators outpace other agents of trait change in the wild. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 952–954 10.1073/pnas.0809235106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0809235106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida T., Jones L. E., Ellner S. P., Fussmann G. F., Hairston N. G. 2003. Rapid evolution drives ecological dynamics in a predator–prey system. Nature 424, 303–306 10.1038/nature01767 (doi:10.1038/nature01767) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fussmann G. F., Loreau M., Abrams P. A. 2007. Eco-evolutionary dynamics of communities and ecosystems. Funct. Ecol. 21, 465–477 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01275.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01275.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law R. 2000. Fishing, selection, and phenotypic evolution. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 57, 659–668 10.1006/jmsc.2000.0731 (doi:10.1006/jmsc.2000.0731) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenberg P. B., Roy K. 2008. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of size-selective harvesting: how much do we know? Mol. Ecol. 17, 209–220 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03522.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03522.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchings J. A., Baum J. K. 2005. Measuring marine fish biodiversity: temporal changes in abundance, life history and demography. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 360, 315–338 10.1098/rstb.2004.1586 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1586) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coltman D. W., O'Donoghue P., Jorgenson J. T., Hogg J. T., Strobeck C., Festa-Bianchet M. 2003. Undesirable evolutionary consequences of trophy hunting. Nature 426, 655–658 10.1038/nature02177 (doi:10.1038/nature02177) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt J. I., Hoef J. M. V., Bowyer R. T. 2007. Antler size of Alaskan moose Alces alces gigas: effects of population density, hunter harvest and use of guides. Wildl. Biol. 13, 53–65 10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[53:ASOAMA]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[53:ASOAMA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen P. 2006. Domestication: from behaviour to genes and back again. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 97, 3–15 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.11.015 (doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.11.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen G. H. M., Andersen I. L., Holand O., Boe K. E. 2011. Differences in the spacing behaviour of two breeds of domestic sheep (Ovis aries): influence of artificial selection? Ethology 117, 597–605 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01908.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01908.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creel S., Winnie J. A. 2005. Responses of elk herd size to fine-scale spatial and temporal variation in the risk of predation by wolves. Anim. Behav. 69, 1181–1189 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.07.022 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.07.022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creel S., Winnie J. A., Christianson D., Liley S. 2008. Time and space in general models of antipredator response: tests with wolves and elk. Anim. Behav. 76, 1139–1146 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.006 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cagnacci F., Boitani L., Powell R. A., Boyce M. S. 2010. Animal ecology meets GPS-based radiotelemetry: a perfect storm of opportunities and challenges. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 2157–2162 10.1098/rstb.2010.0107 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciuti S., Bongi P., Vassale S., Apollonio M. 2006. Influence of fawning on the spatial behaviour and habitat selection of female fallow deer (Dama dama) during late pregnancy and early lactation. J. Zool. 268, 97–107 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2005.00003.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2005.00003.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciuti S., Pipia A., Grignolio S., Ghiandai F., Apollonio M. 2009. Space use, habitat selection and activity patterns of female Sardinian mouflon (Ovis orientalis musimon) during the lambing season. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 55, 589–595 10.1007/s10344-009-0279-y (doi:10.1007/s10344-009-0279-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Said S., Gaillard J. M., Widmer O., Debias F., Bourgoin G., Delorme D., Roux C. 2009. What shapes intra-specific variation in home range size? A case study of female roe deer. Oikos 118, 1299–1306 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17346.x (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17346.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frair J. L., Merrill E. H., Allen J. R., Boyce M. S. 2007. Know thy enemy: experience affects elk translocation success in risky landscapes. J. Wildl. Manage. 71, 541–554 10.2193/2006-141 (doi:10.2193/2006-141) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhly T. B., Semeniuk C., Massolo A., Hickman L., Musiani M. 2011. Human activity helps prey win the predator–prey space race. PLoS ONE 6, e17050. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017050 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morales J. M., Haydon D. T., Frair J., Holsiner K. E., Fryxell J. M. 2004. Extracting more out of relocation data: building movement models as mixtures of random walks. Ecology 85, 2436–2445 10.1890/03-0269 (doi:10.1890/03-0269) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luccarini S., Mauri L., Ciuti S., Lamberti P., Apollonio M. 2006. Red deer (Cervus elaphus) spatial use in the Italian Alps: home range patterns, seasonal migrations, and effects of snow and winter feeding. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 18, 127–145 10.1080/08927014.2006.9522718 (doi:10.1080/08927014.2006.9522718) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grignolio S., Merli E., Bongi P., Ciuti S., Apollonio M. 2011. Effects of hunting with hounds on a non-target species living on the edge of a protected area. Biol. Conserv. 144, 641–649 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.022 (doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proffitt K. M., Grigg J. L., Garrott R. A., Hamlin K. L., Cunningham J., Gude J. A., Jourdonnais C. 2010. Changes in elk resource selection and distributions associated with a late-season elk hunt. J. Wildl. Manage. 74, 210–218 10.2193/2008-593 (doi:10.2193/2008-593) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fryxell J. M., Hazell M., Borger L., Dalziel B. D., Haydon D. T., Morales J. M., McIntosh T., Rosatte R. C. 2008. Multiple movement modes by large herbivores at multiple spatiotemporal scales. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19 114–19 119 10.1073/pnas.0801737105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0801737105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyce M. S., Pitt J., Northrup J. M., Morehouse A. T., Knopff K. H., Cristescu B., Stenhouse G. B. 2010. Temporal autocorrelation functions for movement rates from global positioning system radiotelemetry data. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 2213–2219 10.1098/rstb.2010.0080 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0080) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker K. L., Robbins C. T., Hanley T. A. 1984. Energy expenditures for locomotion by mule deer and elk. J. Wildl. Manage. 48, 474–488 10.2307/3801180 (doi:10.2307/3801180) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortin D., Beyer H. L., Boyce M. S., Smith D. W., Duchesne T., Mao J. S. 2005. Wolves influence elk movements: behavior shapes a trophic cascade in Yellowstone National Park. Ecology 86, 1320–1330 10.1890/04-0953 (doi:10.1890/04-0953) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb S. L., Dzialak M. R., Wondzell J. J., Harju S. M., Hayden-Wing L. D., Winstead J. B. 2011. Survival and cause-specific mortality of female Rocky Mountain elk exposed to human activity. Popul. Ecol. 53, 483–493 10.1007/s10144-010-0258-x (doi:10.1007/s10144-010-0258-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naylor L. M., Wisdom M. J., Anthony R. G. 2009. Behavioral responses of North American elk to recreational activity. J. Wildl. Manage. 73, 328–338 10.2193/2008-102 (doi:10.2193/2008-102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bunnefeld N., Borger L., van Moorter B., Rolandsen C. M., Dettki H., Solberg E. J., Ericsson G. 2011. A model-driven approach to quantify migration patterns: individual, regional and yearly differences. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 466–476 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01776.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01776.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood S. N. 2006. Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Development Core Team 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinheiro J. C., Bates D. M. 2000. Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burnham K. P., Anderson D. R., Huyvaert K. P. 2011. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 23–35 10.1007/s00265-010-1029-6 (doi:10.1007/s00265-010-1029-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greven S., Kneib T. 2010. On the behaviour of marginal and conditional AIC in linear mixed models. Biometrika 97, 773–789 10.1093/biomet/asq042 (doi:10.1093/biomet/asq042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolker B. M., Brooks M. E., Clark C. J., Geange S. W., Poulsen J. R., Stevens M. H. H., White J. S. S. 2009. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 127–135 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnett A. G., Koper N., Dobson A. J., Schmiegelow F., Manseau M. 2010. Using information criteria to select the correct variance–covariance structure for longitudinal data in ecology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 15–24 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00009.x (doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00009.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pebesma E. J. 2004. Multivariable geostatistics in S: the gstat package. Comput. Geosci. 30, 683–691 10.1016/j.cageo.2004.03.012 (doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2004.03.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manly B. F. J., McDonald L. L., Thomas D. L., McDonald T. L., Erickson W. P. 2004. Resource selection by animals: statistical design and analysis for field studies, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic Publishers [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burnham K. P., Anderson D. R. 2002. Model selection and multi-model inference: a practical information-theoretic approach, 2nd edn. New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byers J. A. 1997. American pronghorn. Social adaptations and the ghosts of predators past. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michelena P., Jeanson R., Deneubourg J. L., Sibbald A. M. 2010. Personality and collective decision-making in foraging herbivores. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1093–1099 10.1098/rspb.2009.1926 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1926) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sih A., Bell A., Johnson J. C. 2004. Behavioral syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 372–378 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reale D., Reader S. M., Sol D., McDougall P. T., Dingemanse N. J. 2007. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. 82, 291–318 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson D. S., Clark A. B., Coleman K., Dearstyne T. 1994. Shyness and boldness in humans and other animals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 442–446 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reale D., Gallant B. Y., Leblanc M., Festa-Bianchet M. 2000. Consistency of temperament in bighorn ewes and correlates with behaviour and life history. Anim. Behav. 60, 589–597 10.1006/anbe.2000.1530 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1530) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown J. S., Laundre J. W., Gurung M. 1999. The ecology of fear: Optimal foraging, game theory, and trophic interactions. J. Mammal 80, 385–399 10.2307/1383287 (doi:10.2307/1383287) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodroffe R., Thirgood S., Rabinowitz A. 2005. People and wildlife: conflict or coexistence? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berger J. 2007. Fear, human shields and the redistribution of prey and predators in protected areas. Biol. Lett. 3, 620–623 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0415 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0415) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allendorf F. W., Hard J. J. 2009. Human-induced evolution caused by unnatural selection through harvest of wild animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9987–9994 10.1073/pnas.0901069106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0901069106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wright G. J., Peterson R. O., Smith D. W., Lemke T. O. 2006. Selection of northern Yellowstone elk by gray wolves and hunters. J. Wildl. Manage. 70, 1070–1078 10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1070:SONYEB]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1070:SONYEB]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eberhardt L. L., Pitcher K. W. 1992. A further analysis of the Nelchina caribou and wolf data. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 20, 385–395 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eberhardt L. L., Garrott R. A., Smith D. W., White P. J., Peterson R. O. 2003. Assessing the impact of wolves on ungulate prey. Ecol. Appl. 13, 776–783 10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0776:ATIOWO]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0776:ATIOWO]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunkel K., Pletscher D. H. 1999. Species-specific population dynamics of cervids in a multipredator ecosystem. J. Wildl. Manage. 63, 1082–1093 10.2307/3802827 (doi:10.2307/3802827) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Proffitt K. M., Grigg J. L., Hamlin K. L., Garrott R. A. 2009. Contrasting effects of wolves and human hunters on elk behavioral responses to predation risk. J. Wildl. Manage. 73, 345–356 10.2193/2008-210 (doi:10.2193/2008-210) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klein R. G. 1989. The human career. Human biological and cultural origins. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Steen S., Cullum A. J., Bennett A. F. 2002. Rapid evolution of escape ability in Trinidadian guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Evolution 56, 776–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walsh M. R., Munch S. B., Chiba S., Conover D. O. 2006. Maladaptive changes in multiple traits caused by fishing: impediments to population recovery. Ecol. Lett. 9, 142–148 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00858.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00858.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki K., Fox S. F., Duvall D. 2009. Rapid evolution in the wild: changes in body size, life-history traits, and behavior in hunted populations of the Japanese Mamushi snake. Conserv. Biol. 23, 93–102 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01067.x (doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01067.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]