Abstract

Bacillus spores are highly resistant dormant cells formed in response to starvation. The spore is surrounded by a structurally complex protein shell, the coat, which protects the genetic material. In spite of its dormancy, once nutrient is available (or an appropriate physical stimulus is provided) the spore is able to resume metabolic activity and return to vegetative growth, a process requiring the coat to be shed. Spores dynamically expand and contract in response to humidity, demanding that the coat be flexible. Despite the coat's critical biological functions, essentially nothing is known about the design principles that allow the coat to be tough but also flexible and, when metabolic activity resumes, to be efficiently shed. Here, we investigated the hypothesis that these apparently incompatible characteristics derive from an adaptive mechanical response of the coat. We generated a mechanical model predicting the emergence and dynamics of the folding patterns uniformly seen in Bacillus spore coats. According to this model, spores carefully harness mechanical instabilities to fold into a wrinkled pattern during sporulation. Owing to the inherent nonlinearity in their formation, these wrinkles persist during dormancy and allow the spore to accommodate changes in volume without compromising structural and biochemical integrity. This characteristic of the spore and its coat may inspire design of adaptive materials.

Keywords: bacterial spores, coat, folding, mechanical instability, wrinkles

1. Introduction

Bacillus spores are dormant cells that exhibit high resistance to environmental stresses [1]. Spores consist of multiple concentric shells encasing dehydrated genetic material at the centre (the core). One of these shells is a loosely cross-linked peptidoglycan layer, called the cortex, surrounding the core. Encasing this is the coat, which exhibits a unique folding geometry (figure 1a–c). The coat protects the genetic material while permitting the diffusion of water and small molecules to the spore interior. Paradoxically, the coat must be chemically resilient and physically tough [5–7] but still possess significant mechanical flexibility [4,8,9]. During germination, the coat must be broken apart so that it can be rapidly shed [10].

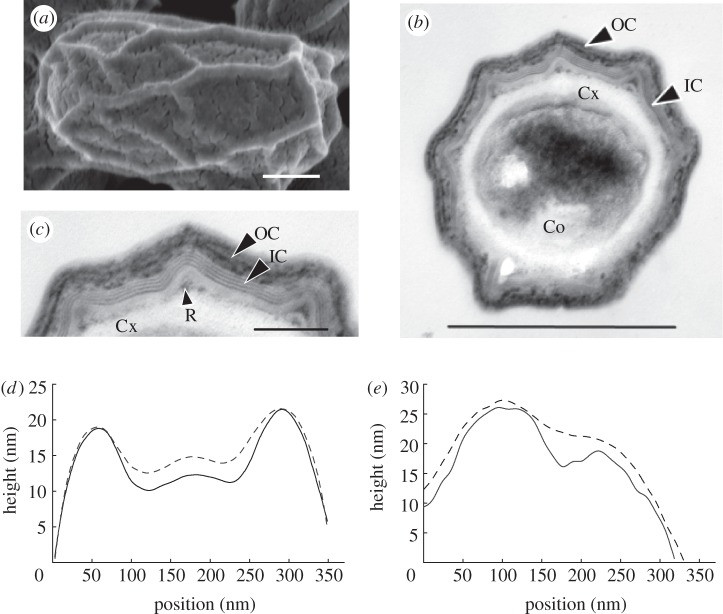

Figure 1.

B. subtilis spore morphology. (a) Wild-type (strain PY79) spores were analysed by SEM, (b,c) TEM [2] (by fixation in glutaraldehyde and osmium, dehydration, embedment in Spurr's resin, and then thin-section transmission electron microscopy) and (d) with AFM height profiles. Separate height profiles obtained on sterne strain of B. anthracis are also given in (e). (c) Is a magnification part of (b). Cortex (Cx), inner coat (IC), outer coat (OC) and a ruck (R) are indicated in (b) and/or (c). The size bars indicate (a) 250, (b) 500 and (c) 100 nm. (The outer most layer of the coat, the crust [3] is not seen because of the fixation method). The spore has an ovoid shape with a long and a short axis [4]. (d) Height profiles measured along the short axis of a spore are recorded at low (35%, solid line) and high (95%, dashed line) relative humidity depict partial unfolding of the wrinkles at a high relative humidity. (e) Height profiles measured for B. anthracis sterne also exhibit partial unfolding of the wrinkles at a high relative humidity. To plot the two curves as closely as possible, an offset is added to the height profiles at a low relative humidity because the overall height of the spore increases with relative humidity. Note that the widths of the spores are larger than the widths of the curves in (d,e), which are plotted across the ridges on top of the spore.

The ridges of the Bacillus subtilis coat emerge during the process of sporulation in which water is expelled from the spore core and cross links occur in the cortex [5,10–14]. The mature spore is not static. It expands and contracts in response to changes in relative humidity [4,8,9]. Although ridges are present in spores of many if not most species [2,15–17] of the family Bacillaceae, these ridges are very poorly understood; we do not understand the forces guiding their formation, how their topography is influenced by the coat's material properties or their biological function, if any.

To address these questions, we first considered that ridges could emerge spontaneously, as in the case of wrinkles that form when a thin layer of material that adheres weakly to a support is under compression [18]. The coat and cortex form such a system, because the core volume (and, therefore, its surface area) decreases during sporulation [19]. Rucks can form if the stress in the system overcomes the adhesive forces between the coat and the underlying cortex [20]. Consequently, we investigated the role of mechanical instabilities in the formation of ridges and the implications of this mechanism for spore persistence.

2. Results

The height profiles of a B. subtilis in figure 1d show that a partial unfolding of the ridges accompanies the expansion of the spore at high humidity. We obtained similar results for Bacillus anthracis spores (figure 1e). Furthermore, fully hydrated Bacillus atrophaeus spores were previously shown to exhibit similar characteristics [4], indicating that this behaviour is not limited to a single species and raising the possibility that it is ubiquitous.

To analyse whether ruck formation can explain the characteristic wrinkle patterns and their response to increased relative humidity, we modelled the coat and cortex as two adhered concentric rings and calculated the response of this structure to gradual reductions in volume, using a combination of scaling analyses and numerical simulations (see the electronic supplementary material). We restricted our model to two dimensions, both because the wrinkle morphology is that of long ridges along the spore, and in order to focus on a minimal model. Typical parameter values in our model are as follows: spore radius Rcoat, and thickness, h, of the coat to be approximately 300 and 40 nm, respectively [2,21,22] (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1), the measured elastic modulus of the B. subtilis coat E approximately 13.6 GPa using an atomic force microscope [23] (AFM), and the energy of adhesion between the coat and the cortex, J, approximately 10 J m−2, associated with non-specific electrostatic interactions between the cortex peptidoglycan [24] and the coat [24,25]. We note that the presence of outer forespore membrane can affect the strength of adhesion between the coat and cortex; however, we assumed that this membrane is no longer present in the mature spore.

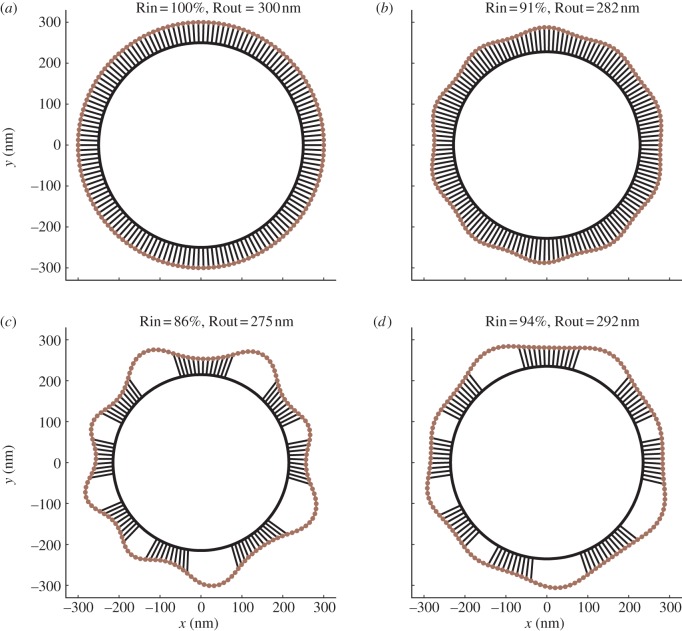

The simulations show that as the rings shrink when the strain is larger than a critical threshold, c, the coat first buckles to form a symmetric wavy pattern around the cortex. This pattern then loses stability to delamination to form rucks (figure 2a–c). Once the rucks are formed, regaining spore volume does not result in reattachment of the coat. Rather, rucks unfold by decreasing their height and increasing their width (figure 2d), in qualitative agreement with our biological observations in figure 1d.

Figure 2.

Model of formation of folds in the spore coat and their response to spore shrinking. (a–c) Simulation of the ruck formation as the radius of spore interior (Rin) shrinks during sporulation. Rin values are given as percentages of the initial value, 300 nm. Rout is the average outer diameter. Using bending and stretching modulus values estimated from thickness and mechanical measurements of the coat, the model predicts the emergence of rucks that are comparable in width, height and number to previous reports [26]. (d) Upon spore expansion, rucks formed during sporulation do not reattach readily, but rather decrease their height and increase their width. Details of simulation results are given in electronic supplementary material, movie S1. (Online version in colour.)

3. Discussion

Wrinkles formed according to the mechanism in figure 2a–c are persistent. They do not readily attach back to the cortex, because they arise owing to a subcritical (nonlinear) instability. This has implications for the dormant spore, because it suggests that after completion of sporulation the spore volume can increase or decrease in response to ambient relative humidity without a significant resistance from the coat. The persistence of rucks ensures that the coat remains in a flexible state, despite large changes in the volume during dormancy [4,8,9], thereby providing a mechanism for maintaining structural integrity of the spore.

The origin of the coat's flexibility in the wrinkled state can be best understood by comparing the energy cost of bending and compression. If the coat were fully attached to the cortex, shrinkage of the spore interior owing to dehydration would have required the coat to be compressed. In contrast, our results indicate that the wrinkled coat expands and shrinks by changing its local curvature. While the energy cost of coat compression scales linearly with the coat thickness Ucompression ∼ h, the energy cost of bending scales with the third power of thickness Ubending ∼ h3. This means that as a layer of material gets thinner, bending becomes easier relative to compression. In the case of spores, reductions in the internal volume of the spore are best accommodated by folding and unfolding of wrinkles.

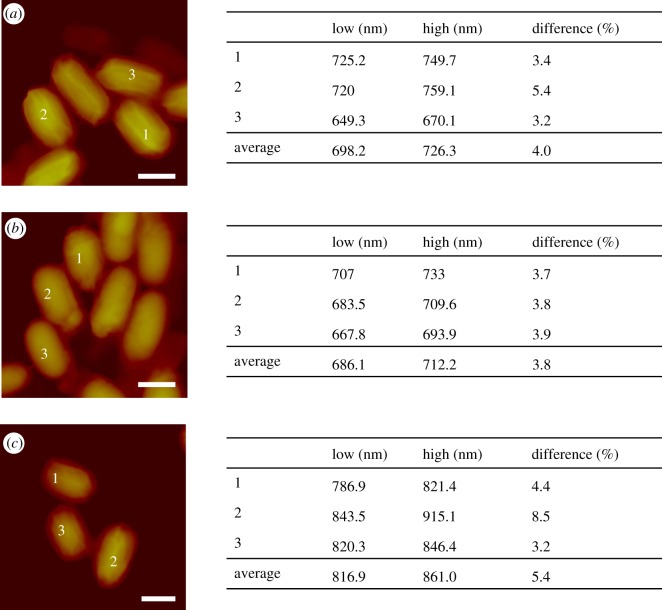

According to the wrinkle model, if the spore internal volume continues to increase, the wrinkles will eventually unfold completely. Beyond that point, the coat will begin to resist any further increase in volume. The biological observation in figure 1d,e that the rucks do not unfold completely suggests that this point is not reached even at very high relative humidity or at full hydration. Therefore, expansion of the dormant spore is not limited by the coat. Instead, the cortex of the dormant spore must have a limited ability to swell. Consistent with this view, B. subtilis spores lacking most of the coat owing to mutations in cotE and gerE [27] were not larger than wild-type spores at a high relative humidity (figure 3). This particular mutant no longer has the resistance properties of wild-type spores, especially to lysozyme; however, they maintain viability in laboratory environment [12,28]. The cortex's limited ability to swell can be explained by its rigidity, as our AFM-based mechanical measurements [23] on the cotE gerE mutant revealed an elastic modulus around approximately 6.9 GPa. A rigid cortex is also needed to sustain pulling forces on the coat, as well as in creating a tight girdle around the dehydrated core.

Figure 3.

(a) Height measurements on wild-type and (b) cotE gerE mutant of B. subtilis, and (c) sterne strain of B. anthracis at low (35%) and high humidity (95%). (a–c) Scale bars, 1 µm. Heights of spores marked on the AFM images are listed on the right for a low and a high relative humidity, together with the percentage of the differences and average values. The mutant B. subtilis spore lacks most of its coat; yet its expansion is comparable to wild-type spores. (Online version in colour.)

The observed architecture and dynamics of the coat and cortex of the dormant spore have important implications for the role of mechanical processes involved in germination, as well. In contrast to the dormant state, the wrinkles disappear in germinating spores [17,19]. Considering our model of wrinkle formation in the coat, a loss of cortex's ability to sustain the pulling forces exerted on the coat can lead to coat unfolding. Degradation of the cortex peptidoglycan during germination can plausibly facilitate this process. In fact, mutant spores that lack the capacity for the degradation of their cortex peptidoglycan still maintain wrinkles in their coats even after triggering germination and partial hydration of their core [29]. We note that according to this mechanism, the unfolding of the coat during germination is not necessarily driven by the expansion of the spore interior, but to a significant degree by the relaxation of the coat to its unfolded state. Because the unfolded and relaxed coat has a larger volume, relaxation of the coat could act like a pump, driving water into the spore. While hydration forces are likely to be primarily responsible for core hydration, a relaxed coat would allow core to absorb a larger volume of water.

Our findings raise the possibility that the mechanical properties of the coat participate in coat shedding, a prerequisite to outgrowth. The B. subtilis coat is shed as two hemispheres during or immediately following germination [19]. Possibly, the coat's mechanical properties play a role in holding these hemispheres together prior to germination, or facilitate their separation prior to the first cell division after germination.

4. Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the coat's global mechanical properties are critical not only during dormancy but also, strikingly, for rapidly breaking dormancy upon germination. We propose that the coat takes advantage of mechanical instabilities to fold into a wrinkled pattern during sporulation and accommodate changes in spore volume without compromising structural and biochemical integrity. Importantly, we argue that the emergent properties of the assembled coat, such as its elastic modulus and thickness [17], rather than specific individual molecular components, are responsible for coat flexibility. In this view, a functional coat can be built in a large number of ways and with diverse protein components. Such freedom in design parameters could facilitate evolutionary adaptation (particularly with respect to material properties) and the emergence of the wide range of molecular compositions and arrangements found among Bacillus spore coats [2,30]. The spore and its protective coat represent a simple paradigm likely used in diverse cell types [31] where regulated flexibility of a surface layer is adaptive, and may inspire novel applications for a controlled release of materials.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding support from the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Rowland Junior Fellows Program, MacArthur Foundation and the Kavli Institute for Bionano Science and Technology.

References

- 1.Nicholson W. L., Munakata N., Horneck G., Melosh H. J., Setlow P. 2000. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 548–572 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000 (doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traag B. A., et al. 2010. Do mycobacteria produce endospores? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 878–881 10.1073/pnas.0911299107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0911299107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKenney P. T., Driks A., Eskandarian H. A., Grabowski P., Guberman J., Wang K. H., Gitai Z., Eichenberger P. 2010. A distance-weighted interaction map reveals a previously uncharacterized layer of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Curr. Biol. 20, 934–938 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.060 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.060) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plomp M., Leighton T. J., Wheeler K. E., Malkin A. J. 2005. The high-resolution architecture and structural dynamics of Bacillus spores. Biophys. J. 88, 603–608 10.1529/biophysj.104.049312 (doi:10.1529/biophysj.104.049312) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driks A. 1999. The Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driks A. 2009. The Bacillus anthracis spore. Mol. Aspects Med. 30, 368–373 10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.001 (doi:10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriques A. O., Moran C. P. 2007. Structure, assembly and function of the spore surface layers. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 555–588 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093224 (doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093224) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driks A. 2003. The dynamic spore. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3007–3009 10.1073/pnas.0730807100 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0730807100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westphal A. J., Price P. B., Leighton T. J., Wheeler K. E. 2003. Kinetics of size changes of individual Bacillus thuringiensis spores in response to changes in relative humidity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3461–3466 10.1073/pnas.232710999 (doi:10.1073/pnas.232710999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Setlow P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 550–556 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001 (doi:10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beall B., Driks A., Losick R., Moran C., Jr 1993. Cloning and characterization of a gene required for assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1705–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driks A., Roels S., Beall B., Moran C. P. J., Losick R. 1994. Subcellular localization of proteins involved in the assembly of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 8, 234–244 10.1101/gad.8.2.234 (doi:10.1101/gad.8.2.234) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin P. A., Fan N., Ricca E., Driks A., Losick R., Cutting S. 1993. An unusually small gene required for sporulation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 9, 761–771 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01736.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01736.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roels S., Driks A., Losick R. 1992. Characterization of spoIVA, a sporulation gene involved in coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174, 575–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley D. E., Franklin J. G. 1958. Electron microscope survey of the surface configuration of spores of the genus Bacillus. J. Bacteriol. 76, 618–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley D. E., Williams D. J. 1957. An electron microscope study of the spores of some species of the genus Bacillus using carbon replicas. J. Gen. Microbiol. 17, 75–79 10.1099/00221287-17-1-75 (doi:10.1099/00221287-17-1-75) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chada V. G., Sanstad E. A., Wang R., Driks A. 2003. Morphogenesis of Bacillus spore surfaces. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6255–6261 10.1128/JB.185.21.6255-6261.2003 (doi:10.1128/JB.185.21.6255-6261.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerda E., Mahadevan L. 2003. Geometry and physics of wrinkling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 074302. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.074302 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.074302) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santo L. Y., Doi R. H. 1974. Ultrastructural analysis during germination and outgrowth of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 120, 475–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolinski J. M., Aussillous P., Mahadevan L. 2009. Shape and motion of a ruck in a rug. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 174302. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.174302 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.174302) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang R., Krishnamurthy S. N., Jeong J. S., Driks A., Mehta M., Gingras B. A. 2007. Fingerprinting species and strains of Bacilli spores by distinctive coat surface morphology. Langmuir 23, 10 230–10 234 10.1021/la701788d (doi:10.1021/la701788d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silvaggi J. M., Popham D. L., Driks A., Eichenberger P., Losick R. 2004. Unmasking novel sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186, 8089–8095 10.1128/JB.186.23.8089-8095.2004 (doi:10.1128/JB.186.23.8089-8095.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahin O., Erina N. 2008. High-resolution and large dynamic range nanomechanical mapping in tapping-mode atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 19, 445717. 10.1088/0957-4484/19/44/445717 (doi:10.1088/0957-4484/19/44/445717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mera M. U., Beveridge T. J. 1993. Mechanism of silicate binding to the bacterial cell wall in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1936–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen G., Driks A., Tawfiq K., Mallozzi M., Patil S. 2010. Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus subtilis spore surface properties as analyzed by transport analysis. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 76, 512–518 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.12.012 (doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.12.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McPherson D., Kim H., Hahn M., Wang R., Grabowski P., Eichenberger P., Driks A. 2005. Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat morphogenetic protein CotO. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8278–8290 10.1128/JB.187.24.8278-8290.2005 (doi:10.1128/JB.187.24.8278-8290.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh S., Setlow B., Wahome P. G., Cowan A. E., Plomp M., Malkin A. J., Setlow P. 2008. Characterization of spores of Bacillus subtilis that lack most coat layers. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6741–6748 10.1128/JB.00896-08 (doi:10.1128/JB.00896-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Setlow P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101, 514–525 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popham D. L., Helin J., Costello C. E., Setlow P. 1996. Muramic lactam in peptidoglycan of Bacillus subtilis spores is required for spore outgrowth but not for spore dehydration or heat resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 15 405–15 410 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15405 (doi:10.1073/pnas.93.26.15405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aronson A. I., Fitz-James P. 1976. Structure and morphogenesis of the bacterial spore coat. Bacteriol. Rev. 40, 360–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elbaum R., Gorb S., Fratzl P. 2008. Structures in the cell wall that enable hygroscopic movement of wheat awns. J. Struct. Biol. 164, 101–107 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.06.008 (doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2008.06.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]