Abstract

The possibility that Bright Yellow 2 (BY2) tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) suspension-cultured cells possess an expansin-mediated acid-growth mechanism was examined by multiple approaches. BY2 cells grew three times faster upon treatment with fusicoccin, which induces an acidification of the cell wall. Exogenous expansins likewise stimulated BY2 cell growth 3-fold. Protein extracted from BY2 cell walls possessed the expansin-like ability to induce extension of isolated walls. In western-blot analysis of BY2 wall protein, one band of 29 kD was recognized by anti-expansin antibody. Six different classes of α-expansin mRNA were identified in a BY2 cDNA library. Northern-blot analysis indicated moderate to low abundance of multiple α-expansin mRNAs in BY2 cells. From these results we conclude that BY2 suspension-cultured cells have the necessary components for expansin-mediated cell wall enlargement.

Plant cells are surrounded by a cell wall composed of cellulose microfibrils embedded in a complex polysaccharide matrix. The plant cell wall has substantial mechanical strength, which must either be overcome or reduced to allow wall extension and cell growth (Cosgrove, 1987; Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993). Our laboratory has identified a group of proteins, named expansins, that enable the growing cell wall to extend, apparently by weakening noncovalent bonding between the matrix and cellulose microfibrils (McQueen-Mason et al., 1992; Cosgrove, 1996). Expansins have an acidic pH optimum and are prime candidates for the agents mediating the “acid-growth” response of plant cell walls (Hager et al., 1971; Rayle and Cleland, 1992). Recently, a second group of proteins, previously know as group-1 allergens from grass pollen, was identified as a second family of expansins (Cosgrove et al., 1997). These proteins are called β-expansins to distinguish them from the original class of expansins, referred to as α-expansins. Both α- and β-expansins comprise large multigene families (Shcherban et al., 1995; Cosgrove et al., 1997). Judging from the number of expressed genes identified to date in the Arabidopsis and rice expressed sequence tag databases, it appears that β-expansins may have assumed specialized roles for cell wall loosening during the evolutionary divergence of the grasses (Cosgrove et al., 1997). Despite the growing multitude of expansin genes being discovered, questions remain about the generality of expansin-mediated growth. To address this question, we have studied the growth of Bright Yellow 2 (BY2) tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L) suspension-cultured cells.

Plant cell suspensions have been favorite subjects for studies of cell growth and wall biochemistry, in part because their walls are more homogeneous than those of complex tissues (McNeil et al., 1984; Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993). Because cell suspensions are in constant contact with the medium, exogenous proteins have ready access to the cell walls. This is an important advantage for testing the ability of exogenous wall enzymes to modulate plant cell expansion.

Although plant cell cultures are sensitive to pH, an acid-growth response has not been demonstrated, and we do not know if expansins function in this cell type. Published evidence suggests that cell-suspension cultures do not show acid-growth responses (Nesius and Fletcher, 1973; Smith and Krikorian, 1992; Roberts and Haigler, 1994). In this investigation we examined the possibility that BY2 tobacco cell cultures possess an expansin-mediated growth mechanism. If this were the case, we would predict that: (a) BY2 cell growth would be responsive to fusicoccin-induced wall acidification and to application of expansins; (b) BY2 cell walls would contain active expansins, and (c) BY2 cells would express one or more expansin genes. The results of these tests were found to support the involvement of expansins in BY2 cell enlargement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culturing

Suspension cultures of BY2 tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) were maintained at 22°C for 12-h days/12-h nights in 500-mL Erlenmeyer flasks on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm. Every 7 d, 2 mL of culture was transferred to a new flask containing 100 mL of BY2 medium (4.3 g/L Murashige and Skoog salts, 30 g/L Suc, 1 mg/L thiamine HCl, 255 mg/L KH2PO4, 0.2 mg/L 2,4-D, and 100 mg/L myo-inositol) (Nagata et al., 1981).

Cell-Growth Assays

Cell enlargement was monitored with a video camera attached to an inverted microscope. Cells were attached to coverslips by two methods. For the first method, 15 mL of a 6-d-old culture was centrifuged for 5 min at 800g and 1 mL of liquid was drawn from the cell-liquid interface. For the agarose-embedding technique, the cells were mixed with 1 mL of BY2 medium containing 1.2% agarose (premelted and cooled to 40°C; Sigma no. A-9539) and spread thinly over a sterile coverslip (48 × 65 mm) on a 40°C heat block. The coverslip was placed in a Petri dish and allowed to harden for 30 min, and 1 mL of “conditioned” medium from the centrifuged culture was spread over the top of the agarose, creating a liquid layer 0.32 mm deep. The remaining conditioned medium was transferred to a new tube and stored at 4°C for use later in the assay. Five cell groups, each containing 5 to 15 cells lying in the focal plane, were chosen for microscopic analysis at 64× magnification. After a 24-h recovery period we recorded images of the cells on videotape. Twelve hours later we recorded their images once each hour for 8 h to determine their basal growth rate. The liquid over the agarose was then removed and replaced with 1 mL of conditioned medium plus the appropriate treatment: 1 μL of 1 mm fusicoccin in 50% ethanol or 20 μL of C3 purified cucumber expansins (approximately 1.0 μg/μL in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5; see below for C3 protein preparation). Controls were given either 1 μL of 50% ethanol or 20 μL of 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5. We recorded images once an hour for an additional 8 h and recorded a final image 20 h after the treatment.

In a second version of this assay, each coverslip was treated with poly-l-Lys (0.5 g/L in 50% ethanol; Sigma no. P1524). One milliliter of the liquid and cells was drawn off from the centrifuged cells as described above and applied to the coverslip. The cells were allowed to recover overnight, and the medium was removed and replaced with fresh conditioned medium just before beginning hourly recordings. The assay then proceeded as described above. Despite the reduction in recovery time, this assay produced results similar to those of the agarose method.

Images were analyzed using the National Institutes of Health Image software on a Macintosh Quadra 800 computer with a Scion LG 3 graphics board by tracing the perimeter of the cell groups for each time point and calculating the area within the perimeter. Data are presented as percent change in area compared with the smallest (generally the initial) area for a cell group.

Weight Assay

Three 25-mL aliquots from a culture were placed in separate 125-mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Two of the aliquots (the first and the last) were used as controls. To the second aliquot was added 12.5 μL of 1 mm fusicoccin in 50% ethanol (giving a final concentration of 500 nm). An equal amount of ethanol was added to the controls. The three aliquots were grown for 5 h. The contents were transferred to 50-mL tubes, weighed, and centrifuged for 10 min at 800g. After removal of the free culture medium, the packed cells were weighed. Cell density was calculated as a simple weight percentage of the culture.

Protein Extraction and Expansin Activity Assay

Wall proteins were extracted as described previously (McQueen-Mason et al., 1992), except that 1 mm DTT was added to the grind and extraction buffers to maintain expansin activity. Six-day-old BY2 cells were collected by centrifugation in 50-mL tubes for 10 min at 800g, suspended in grind buffer (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, 2 mm sodium metabisulfite) to make 100 mL, and homogenized for 30 s in a chilled Waring blender. The mixture was allowed to settle for 1 min on ice, homogenized again for 30 s, and centrifuged at 800g for 10 min. The pellet was washed by resuspension in grinding buffer and centrifugation, then resuspended in twice its volume of extraction buffer (20 mm Hepes, 2 mm EDTA, 3 mm sodium meta-bisulfite, and 1 m NaCl, pH 7.0), and extracted for 30 min with agitation at 4°C. The mixture was centrifuged to pellet the walls and additional debris, which were discarded. Some proteins were removed from the supernatant by centrifugation after addition of 113 g/L ammonium sulfate. Subsequent centrifugation after addition of another 277 g/L ammonium sulfate yielded a crude wall protein fraction containing expansin. This was resuspended in 1 mL of 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5, plus 1 mm DTT and immediately tested for expansin activity by reconstitution assays with heat-inactivated walls from cucumber hypocotyls, as described previously (Wu et al., 1996).

For western-blot analysis the proteins were prepared using published methods (McQueen-Mason et al., 1992; Keller and Cosgrove, 1995). The ammonium sulfate precipitate of wall protein was desalted on a Centricon 30-kD spin column and the proteins were separated by HPLC on a C3 hydrophobic interactions column (ISCO Synchropak C-3/65 μm, Lincoln, NE). The relevant fractions were collected and electrophoresed into a 15% SDS polyacrylamide gel. Prestained markers (6–60 kD, GIBCO-BRL) were used for molecular mass standards. The gels were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, which were probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody made to cucumber S1 expansin (Li et al., 1993).

RNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and cDNA Library Screening

BY2 cells were collected by centrifugation at 800g for 5 min and placed on ice. Packets of 1.2 g of packed cells were weighed out and frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (GIBCO-BRL) using the manufacturer's protocol. Poly(A+) RNA was isolated using the PolyAtract system (Promega) and used for either northern-blot analysis or reverse-transcription PCR. We used Superscript II (GIBCO-BRL) for reverse transcription and degenerate primers (sense primer, GGHGGNTGGTGYAAYCC; antisense primer, ACCDBNAARCCDGTYTG) to amplify expansin fragments from the tobacco first-strand cDNA. Two fragments were isolated, cloned using TA cloning (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), and sequenced using standard methods (Sambrook et al., 1989). The larger fragment was used to screen a BY2 cDNA library obtained from Lee McIntosh (Michigan State University, East Lansing) (Vanlerberghe and McIntosh, 1994). Once sequences for the tobacco expansins were obtained, they were used to predict protein sequences, including signal peptides. The cleavage sites of the signal peptides were predicted using the SignalP program available on the Internet at The Center for Biological Sequence Analysis, the Technical University of Denmark (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/signalp/) (Henrik et al., 1997). Tobacco sequences were assigned accession nos. AF049350 to AF049355.

We aligned the tobacco protein sequences with other published α-expansin sequences by first using the PileUp program (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI) (gap penalty = 3.00, extension penalty 0.10). The ESEE (Eyeball Sequence Editor, version 2.0) program was then used to create a corresponding alignment of the nucleotide sequences (Cabot and Beckenbach, 1989). We generated a phylogenetic tree from this alignment using the MEGA program with the neighbor-joining method and Kimura two-parameter distances with the complete deletion option (Kumar et al., 1993).

RESULTS

BY2 Cells Grow Faster in Response to Fusicoccin

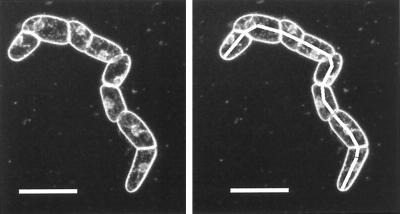

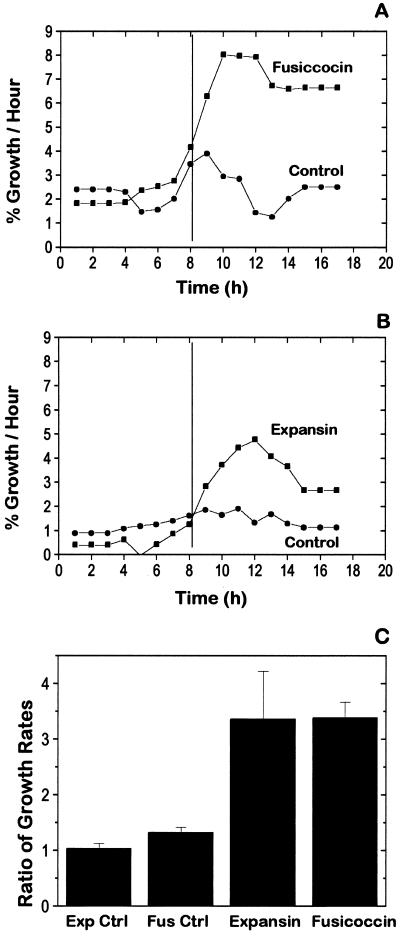

Figure 1 shows that BY2 cells selected for analysis grew as cell files under our culture conditions. To determine if BY2 cells have an acid-growth response, we measured their growth response to fusicoccin. This fungal toxin activates the H+-ATPase in the plasma membrane, causing strong acidification of the cell walls and thereby inducing rapid cell elongation (Marré, 1979; Kutschera and Schopfer, 1985). The size of BY2 cell clusters was measured at 1-h intervals before and after treatment with fusicoccin. Figure 2A shows that BY2 cells enlarged faster, by 2- to 3-fold, after treatment with fusicoccin.

Figure 1.

Microscope image of a typical BY2 cell group showing how measurements were made. Images of cell groups were recorded once an hour on videotape. At the end of an experiment the images were captured by a graphics board and National Institutes of Health Image software was used to trace outlines of cell groups and to calculate the area inside of the perimeter. All growth data are expressed as percent change in an optical cross-sectional area. The trace on the right image shows how lengths were measured. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Effect of fusicoccin or expansin on growth rates of BY2 cells. Individual growth-rate data (based on optical cross-sectional areas) for four sets of cells in a growth assay were averaged to produce a single growth-rate curve for the experiment. Five-point Savitsky-Golay smoothing was used to reduce the noise inherent in rate data. This accounts for the apparent spreading of the growth response to times preceding treatment. A, At 8 h, cells were treated with either 1 μL of fusicoccin (final concentration 500 nm) or an equivalent amount of ethanol (control treatment). B, At 8 h, cells were treated either with approximately 20 μg of C3 cucumber expansin (1 μg/μL) in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5, or with an equivalent amount of sodium acetate (controls). C, Bar chart comparing the average ratio (growth rate for the 8-h period after treatment divided by the growth rate for the 8-h period before treatment) and se for all experiments. The average growth rates before treatments were: expansin controls (Exp Ctrl), 1.60%/h (se = 0.12%/h, n = 35); fusicoccin controls (Fus Ctrl), 1.96%/h (se = 0.22%/h, n = 15); expansin, 1.36%/h (se = 0.15%/h, n = 35); and fusicoccin, 1.71%/h (se = 0.51%/h, n = 14).

To determine the growth anisotropy, we measured the lengths and widths of seven groups of cells during their fusicoccin response. The average length of the files increased over 16 h by 24.9% (se = 3.6%, n = 7), whereas the average width increased only 3.9% (se = 6.1%, n = 7). Cells were also observed to divide during the experiments, increasing the average number of cells per file from 8.9 (se = 1.7, n = 7) to 12.6 (se = 1.3, n = 7). These data show that BY2 cells grow principally by elongation in these experiments.

The fusicoccin response was also confirmed in bulk weight assays. In five trials, BY2 cells treated with fusicoccin weighed 21.8% (se = 3.4%, n = 5) more than the untreated controls after 5 h. In one experiment the pH of the medium was measured and found to decrease from 6.4 to 5.6 5 h after fusicoccin treatment. These results show that BY2 cells have a strong growth and acidification response to fusicoccin. Because fusicoccin stimulates growth principally via an acid-growth mechanism (Kutschera and Schopfer, 1985), which is mediated via expansins (Cosgrove, 1996), we infer from these results that BY2 cells possess an endogenous, expansin-mediated acid-growth mechanism.

BY2 Cells Grow Faster after Application of Expansins

Cell-growth assays were also used to determine the effect of exogenous expansins on cell expansion. Figure 2B shows that BY2 cells increased their growth rate by 2- to 3-fold after treatment with exogenous cucumber expansins. To quantify and compare this effect, we calculated average growth rates for the 8 h before and the 8 h after treatment. The ratios of these two rates are shown in Figure 2C. Expansin increased the growth rate by 337% (n = 34, se = 86.2%), an effect nearly the same as the growth stimulation by fusicoccin, 339% (n = 14, se = 28.2%). Whereas the average growth stimulation was the same for fusicoccin and expansin, the se was much larger for expansins.

The data shown in Figure 2B suggest that expansin-induced growth was reduced during the last 4 h of the experiment. To determine if this was typical, we compared the growth rates of individual cell groups for the first 4 h and the second 4 h after treatment. The average ratio for the first 4-h period was 3.7 (se = 1.06, n = 26) compared with 3.6 (se = 1.2 n = 26) for the second 4-h period. Thirteen cell groups had higher growth rates during the second 4 h, whereas 13 had lower rates. From these data we conclude that there is no statistical difference in growth response between the first and second 4 h after expansin treatment.

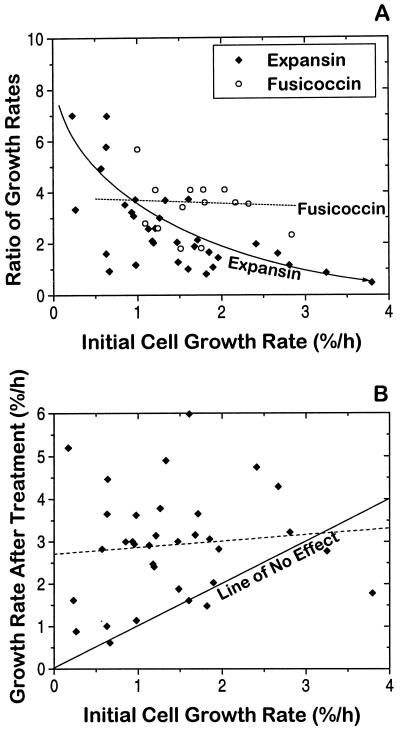

Figure 3A shows that the high variability in the expansin response was inversely related to the initial growth rate of the cells. Cells with a low initial growth rate gave the greatest response to expansin, whereas rapidly growing cells gave less response (on a percentage basis). Fusicoccin treatments tended to produce approximately the same response (approximately 3-fold stimulation) regardless of the initial growth rate. The fusicoccin data set is smaller than the expansin data set and does not cover as broad a range of growth rates. Nonetheless, it appears that the response to expansin treatment was more sensitive to the initial growth rate. These data suggest that expansin proteins are partially limiting for growth at low growth rates, but not at high growth rates.

Figure 3.

Fusicoccin- and expansin-growth responses as a function of initial growth rate. A, Growth response as a function of pretreatment growth rate. The increase in growth rates for cell groups (growth rate after treatment divided by growth rate before treatment) was plotted against the initial (pretreatment) growth rate. The solid and dotted lines represent least-squares fits for the expansin and fusicoccin data, respectively. The line for the expansin data is an exponential decay fit. The dashed line for the fusicoccin data is a first-order fit. B, The growth rate after treatment with expansins is plotted against the pretreatment growth rate. The solid diagonal line (slope = 1) represents where the data would fall if expansin treatment had no effect. The dashed line is a least-squares fit of the data and has a slope of 0.145 ± 0.252, and a y intercept of 2.71%/h. All growth rates were based on change in the optical cross-sectional area versus time.

To explore this question further, we plotted the initial growth rates versus the final growth rates for the expansin data set in Figure 3B. The solid diagonal line (slope = 1) is the predicted line if expansin treatment had no effect. If expansin addition stimulated growth by a constant amount (e.g. 2%/h), the points should fall on a line parallel to (and above) this diagonal line. If, on the other hand, the addition of expansin became saturating for growth, the points should fall on a horizontal line, with a slope of 0. A least-squares fit of the rate data gave a line having its y intercept at 2.7 ± 0.4%/h and a slope that is indistinguishable from 0 (0.14 ± 0.25). This result is consistent with a saturation response and suggests that endogenous expansins are rate limiting for slowly growing BY2 cells, but may be near saturation for rapidly growing cells.

Because the expansin protein was resuspended in sodium acetate buffer, both the expansin-treated and the control cell groups were exposed to 1 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5, in their medium. To determine what effects this weak buffer might have on the pH of the medium, we added sodium acetate buffer to 6-d-old-cultured cells. The pH of the medium immediately decreased to 4.5, but recovered to its initial value of 5.5 in 10 min. Figure 2C shows that only the expansin-treated cells showed a significant increase in growth rate, and that the sodium acetate buffer did not affect the growth rate of the cells during the course of the experiment.

BY2 Cell Walls Contain Expansin Proteins

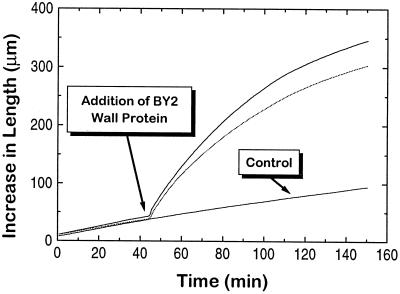

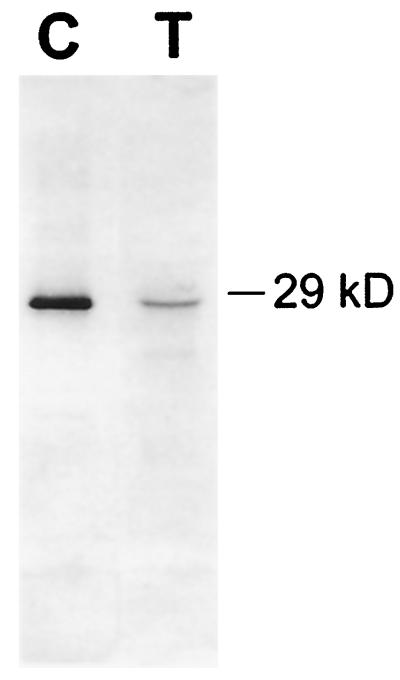

Because we were able to demonstrate a fusicoccin growth response and sensitivity to exogenous expansins in BY2 cells, we analyzed their walls for native expansins using a wall extension (creep) assay. Figure 4 shows that protein extracted from BY2 walls has expansin-like activity. Protein from the medium and from the protoplasmic fraction of the cell homogenate did not exhibit any expansin-like activity (data not shown). From this result we conclude that BY2 cells have expansin-like proteins bound to the cell wall. This conclusion was supported by western-blot analysis of the BY2 wall probed with antibody raised against cucumber S1 α-expansin protein (Fig. 5). The anti-expansin antibody recognized a band with similar molecular mass as cucumber α-expansin. The relatively weak signal found with the BY2 proteins could be caused by low relative abundance of extractable expansins in the BY2 cell walls, weak recognition of BY2 expansins by the antibody, or a combination of these two effects. The western-blot data, together with the results of the fusicoccin and wall-extension assays, indicate that BY2 cultures produce their own active α-expansins.

Figure 4.

Results of extension assays using wall protein extracted from BY2 cells. Heat-inactivated wall specimens from cucumber hypocotyls were placed in the extensometer under 20 g of tension, and bathed in 200 μL of 50 mm sodium acetate at pH 4.5. Their initial creep rates were recorded for 45 min, after which time the buffer for two of the cuvettes was replaced with 200 μL of the BY2 wall protein extract, which was resuspended in 50 mm sodium acetate at pH 4.5. Total wall protein concentration was approximately 170 μg/mL. Initial length of the wall sample was 5 mm. Extension assays were done on four separate occasions with similar results.

Figure 5.

Western blot of partially purified cucumber and tobacco cell wall proteins probed with antibodies to cucumber α-expansin. Wall proteins from the expansin-containing fractions of an HPLC C3 hydrophobic interactions column were electrophoresed into a 15% SDS-PAGE gel, blotted, and cross-reacted with a polyclonal antibody raised against cucumber S1 α-expansin (Li et al., 1993). Lane C, One microgram of cucumber hypocotyl wall protein; lane T, 10 μg of tobacco proteins. Western-blot analysis was done on five separate occasions with similar results.

BY2 Cells Express Multiple α-Expansin Genes

To identify the α-expansins expressed by BY2 cells, we used a degenerate oligonucleotide primer pair to amplify a fragment of a tobacco expansin cDNA by reverse-transcription PCR. This produced two unique fragments that were cloned, sequenced, and confirmed to code for α-expansins. One fragment was 331 bp and the other was 377 bp. The 377-bp fragment was used to probe a cDNA library made from 3-d-old BY2 cells. An initial screening of 60,000 plaques produced 24 positives. Restriction mapping and partial sequencing demonstrated that these corresponded to six unique classes of α-expansins. Class I (NTEXP1) contained 11 clones; class II (NTEXP2), 2 clones; class III (NTEXP3), 6 clones; class IV (NTEXP4), 2 clones; class V (NTEXP5), 2 clones; and class VI (NTEXP6), 1 clone. A full-length or nearly full-length sequence was obtained by sequencing the largest member of each class. The cDNAs ranged in size from 1.17 to 1.45 kb. We isolated only partial clones for NTEXP5 and NTEXP6. The largest clone for NTEXP5 appeared to be missing the starting Met, whereas the largest clone for NTEXP6 was missing about 60 amino acids at the N terminus, as well as the signal peptide. The 377-bp PCR fragment is from NTEXP1, whereas the 331-bp PCR fragment is identical to a portion of NTEXP6.

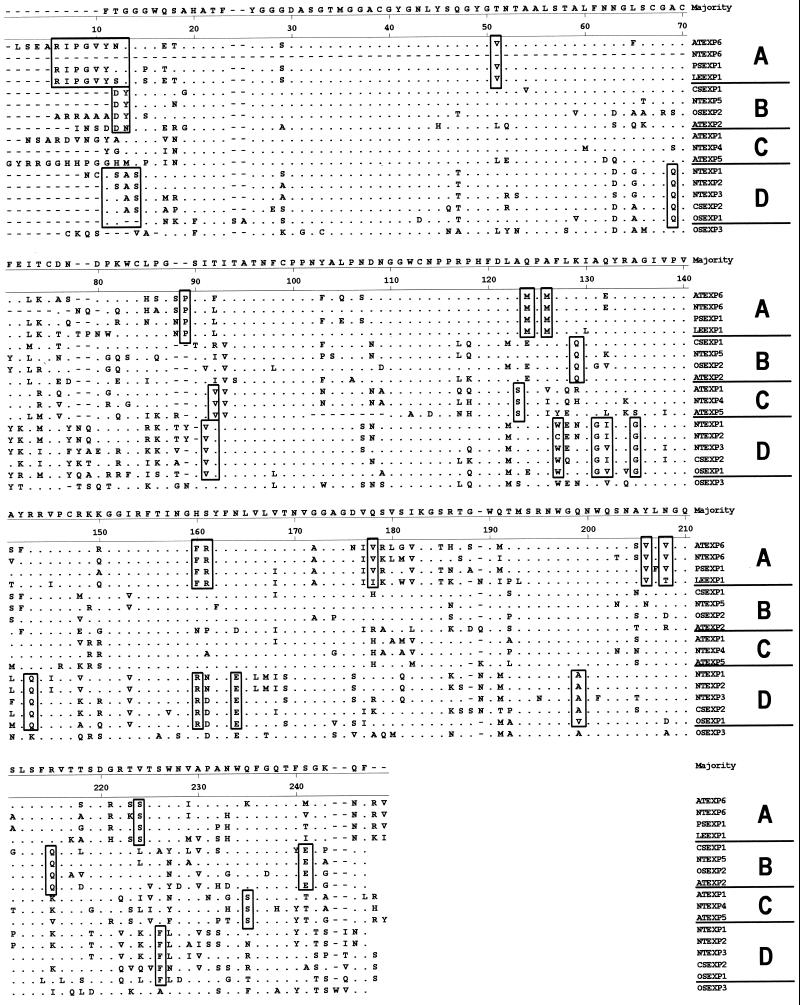

An alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences for the tobacco expansins with other expansins is shown in Figure 6. The tobacco α-expansin cDNAs encode proteins containing a signal sequence of approximately 23 amino acids and a 233-amino acid conserved region ending with a stop codon. All of the cloned sequences contain the conserved domains described previously for α-expansins (Shcherban et al., 1995; Cosgrove, 1996). α-Expansins contain eight Cys residues, which are conserved in NTEXP1-NTEXP5; we do not have a sequence for this portion of NTEXP6. Expansins have four conserved Trp residues near the C terminus. These are shown at positions 190, 197, 201, and 234 in Figure 6. They are similarly spaced to Trp residues in the cellulose-binding domain of cellulases (Gilkes et al., 1991; Poole et al., 1993; Shcherban et al., 1995). These Trp residues are conserved in all of the tobacco expansins except for NTEXP3, in which the third Trp is substituted with Phe.

Figure 6.

Amino acid alignment of previously published expansin sequences with predicted sequences from the tobacco cDNAs. Areas with dots are identical to the consensus sequence, and dashes are used to indicate gaps in the alignment. The order of sequences matches the order on the phylogenetic tree in Figure 7. The large letters along the right margin indicate the α-expansin subfamily shown in Figure 7. Changes in amino acids that appear to be conserved among subfamilies are boxed. The sequence for NTEXP6 is missing at least the first 60 amino acids. Dashes were inserted in this area to align it with the other sequences.

The tobacco sequences have 60% to 80% identity within the 233-amino acid conserved region to other known α-expansins. This degree of identity is similar to that found in α-expansin sequences of Arabidopsis and cucumber. The exceptions to this rule are NTEXP1 and NTEXP2, which differ from each other at only 5 amino acids within this same region and share 95% identity at the nucleotide level. Overall, the sequence divergence of tobacco α-expansins is as large as that of α-expansins among all species.

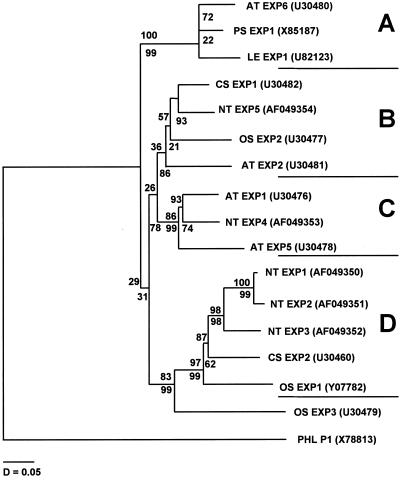

Figure 7 shows a phylogenetic tree that is based on the nucleotide sequences for the protein alignment shown in Figure 6. The distribution of the tobacco expansins in this tree suggests that there are subgroups of α-expansins distinguishable by their sequence. Some of the subfamilies have identifying domains in their 5′ nonconserved regions. In addition to the 5′ identifiers, some changes within the expansins appear to be conserved within a subfamily. These changes are boxed in Figure 6 and may indicate significant subdomains. NTEXP6 is not shown on the tree because it is a partial clone, and when it was included, it biased the estimation of branch lengths. When it was included in the analysis, it branched with the group A α-expansins.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences and the alignment of expansins presented in Figure 6. The third position of each codon was excluded, because it is likely to be saturated with mutations. The tree was produced by the MEGA program using the neighbor-joining method, with Kimura two-parameter distances with the complete deletion option. Bootstrap values are given above the branches and confidence probability values are indicated below. The tree was rooted using Phleum pollen allergen (PHL P1). Accession numbers are given after the gene names. The names are given according to our current naming convention, in which the letters EXP designate expansin and the first two letters indicate the genus and species: AT for Arabidopsis, CS for cucumber (Cucumis sativus), LE for tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), NT for tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), OS for rice (Oryza sativa), and PS for pea (Pisum sativum). Lengths of the branches represent nucleotide distances.

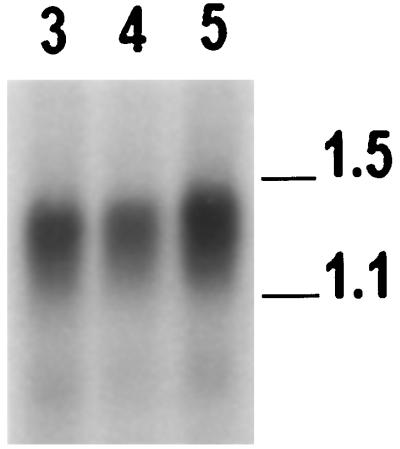

To confirm that α-expansins are expressed in the BY2 cell culture, a northern blot of 2 μg of poly(A+) RNA was probed with NTEXP1 and washed under stringent conditions (Fig. 8). A diffuse band or an overlapping series of bands was observed between 1.1 and 1.5 kb, corresponding to the range in size of the cloned cDNAs. The high homology of α-expansins would allow the probe to cross-hybridize with all of the known members of the α-expansin family. The results of the northern-blot analysis confirm that BY2 cells transcribe α-expansins.

Figure 8.

Northern-blot analysis of BY2 mRNA. Two micrograms of BY2 poly(A+) RNA was loaded for each lane. The blot was probed with a probe made to the full-length NTEXP1 cDNA. The numbers above the lanes indicate the ages of the cells in days. The numbers on the right indicate the sizes of the RNAs in kilobases. Northern-blot analysis was repeated on at least five separate occasions with similar results.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, acid growth has not been previously reported in cell cultures. Other investigators have looked at the long-term effect of pH on cultures and reported results apparently at odds with the acid-growth hypothesis. For zinnia mesophyll cultures (Roberts and Haigler, 1994), carrot embryo cultures (Smith and Krikorian, 1992), and rose cell-suspension cultures (Nesius and Fletcher, 1973), low-pH values promoted cell division, whereas cell expansion and elongation seemed to require a slightly higher pH. In zinnia mesophyll cultures the optimal pH for cell elongation was 5.5 to 6.0, whereas cell differentiation occurred when the pH of the medium decreased to 4.8. Smith and Krikorian (1992) showed that embryonic carrot cells elongate only when the pH of the medium is greater than 4.5, and that elongated cells appear in the culture even if the pH is buffered to 5.8. Based on these results they concluded that some mode of growth other than acid growth may be responsible for cell elongation in cell cultures.

Cell cultures are known to be very sensitive to their external environments, and hence these studies all have the caveat that the pH may affect the cell physiology in complex ways. External pH affects uptake of auxin, metabolites, and various nutrients; it can shift the cell's internal pH, which may act as a secondary messenger; and it can affect the concentration of calcium in the cell wall. Any of these factors may alter the long-term growth of the cell and may obscure the process of acid-induced wall extension. Because of these concerns, we analyzed cell expansion over short periods (less than 24 h) to avoid the any long-term secondary effects of our treatments. We used fusicoccin to stimulate acid growth to avoid the toxic effects of the high buffer concentrations that would be needed to reduce the pH of the strongly buffered cell wall space (Kutschera and Schopfer, 1985; Kutschera, 1994).

The induction of BY2 cell enlargement by exogenous expansins (Figs. 2B and 3) suggests two important conclusions: that expansins are able to induce wall extension in living cells at physiologically relevant pH values (most previous work was done with isolated walls at pH 4.5), and that the abundance of endogenous expansin is below saturation for growth of BY2 suspension-cultured cells. From these conclusions it follows that regulation of expansin activity in vivo is a viable mechanism for regulating the rate of cell expansion.

The results of these experiments also raise an interesting conundrum. Whereas expansins have a pH optimum of less than 4.5 in vitro (Cosgrove, 1989; McQueen-Mason et al., 1992), the pH of 6-d-old medium for our BY2 cultures is typically around 5.5, a value more than 1 pH unit above the optimum for expansin activity. Nevertheless, exogenous expansins increased cell growth rates in these cultures. The concentration of expansins added to the BY2 cultures in these experiments was not likely to be excessive (unphysiological) because (a) it was equivalent to the concentration required to give moderate extension responses in isolated walls, and (b) at this concentration the amount of exogenous expansin that binds to cell walls is approximately equivalent to the amount of native expansin extractable from growing cucumber hypocotyl walls (i.e. about 1 part expansin to 5000 parts wall on a dry-weight basis [McQueen-Mason and Cosgrove, 1995]). The fact that expansin can stimulate cell enlargement in cultures with a bulk pH of 5.5 suggests that it can induce wall extension in vivo at a pH above the optimum observed in vitro. The likeliest explanation for this difference is that proton pumping, acting at the plasma membrane, reduces the local pH in the inner part of the cell wall. The high concentration of fixed carboxyl groups in the wall would give the wall a strong buffering capacity, thus allowing steep pH gradients within the wall. It is also possible that the BY2 cells are able to modify the optimal pH at which expansin functions in muro.

The BY2 cell-growth response to exogenous expansin was at least partly dependent on the cell's previous growth rate (Fig. 3A). This may reflect saturation of the wall with expansins. The abundance of expansins may be a rate-limiting factor as the cell goes from a slowly growing to a rapidly growing state; hence, in this state application of exogenous expansins has a relatively large effect. This conclusion is supported by Figure 3B, which indicates that on average there is a maximal growth rate for BY2 cells of about 2.7%/h when exogenous expansins are applied, regardless of the cell's initial growth rate. Fusicoccin's ability to increase the growth rate was not dependent on the initial growth rate of the cell. In growing cells fusicoccin is able to increase the growth rate by decreasing the pH, thus enhancing the activity of the expansins that are already there. It is interesting to note that this implies that the cell wall space is rarely at the optimal pH for expansin activity. This is the ideal situation for the use of pH modulation to regulate cell wall enlargement.

Sequence analysis of expansins from a variety of plants has given hints about which parts of the expansin protein may be important to its function (Cosgrove, 1996). Inclusion of the tobacco sequences in the phylogenetic tree suggests that there are at least four subgroups of α-expansins. When NTEXP6 is included on the tree there is a tobacco expansin in each of the subgroups. Each subgroup has conserved changes away from the consensus at particular sites within the protein and has members from two or more species. This suggests that each group may be tailored for a specialized function, e.g. to act on walls of differing compositions or under different wall conditions. These groupings may help us to identify orthologous expansins from different species, as well as aid us in identifying key domains or residues within the protein.

At present there is little information about the expression patterns of the many expansin genes, and it will be of interest to determine if the expansins within a given subgroup are expressed in similar tissues in the different plant species. Currently, we can give a partial evaluation of subgroup A (Fig. 7). The expression patterns for the Arabidopsis and tobacco genes (ATEXP6 and NTEXP6) are uncertain. The tomato expansin LEEXP1 is expressed most highly in ripening tomato fruits (Rose et al., 1997), whereas the pea expansin (shown as PSEXP1) is most highly expressed in flower petals (Michael, 1996).

One unusual feature of the tobacco expansins is the very high sequence similarity of NTEXP1 to NTEXP2 (95% at the nucleotide level). This is the highest similarity that we have yet found between two expansin genes. N. tabacum was probably produced by crossing Nicotiana sylvestris and Nicotiana tomentosiformis, creating a species carrying the genomes of both parents (Akehurst, 1970). It is possible that these two clones represent orthologous genes from each of the parent species. Alternatively, they may be the products of an evolutionarily recent duplication and divergence of an expansin gene.

Four lines of evidence indicate that BY2 suspension-cultured cells use expansins for cell enlargement. The cell-growth response to fusicoccin showed that BY2 cells have an acid-growth mechanism. Extension (creep) assays showed that BY2 cells contain cell wall proteins with expansin-like activity. Western-blot analysis showed that the BY2 cell wall protein contained one or more proteins that cross-react with anti-expansin antibodies and that are similar in size to cucumber expansins. Finally, northern-blot analysis detected poly(A+) RNAs of sizes consistent with the known cDNAs from a tobacco BY2 library. A clear signal could only be obtained with poly(A+) RNA, not with total RNA, indicating a relatively low abundance of transcripts. In contrast, signals were readily detectable in total RNA from cucumber hypocotyls (J. Shi, M. Shieh, and D.J. Cosgrove, unpublished results), rice tissues (Cho and Kende, 1997), and ripening tomato fruit (Rose et al., 1997). BY2 cells typically grow at rates of 2%/h, in comparison with 10%/h for the fastest-growing cells of the cucumber hypocotyl. The results of our northern- and western-blot analyses indicate that expansin gene expression is relatively low in BY2 cells, consistent with the relatively low growth rates in these cells.

Despite their relatively low abundance in northern blots, α-expansins were highly represented in a BY2 cDNA library. Very few (60,000) plaques were screened, but six different cDNAs were identified. The number of expansins expressed in the suspension culture is remarkable. We suggest that the BY2 culture cells are in a developmentally confused state, and that individual α-expansins are probably expressed in very specific patterns in planta. When more than 500,000 plaques were screened from a cDNA library made from cucumber hypocotyls, only two expansins were identified (Shcherban et al., 1995).

In this study we have demonstrated that BY2 suspension cells have an acid-growth response and that they enlarge more quickly when they are treated with exogenous expansins. Significantly, expansins have been shown to work in vivo when the pH of the medium is near 5.5. The susceptibility of a cell to exogenous expansin correlates with its pretreatment growth rate, suggesting that the presence of expansins may be a rate-limiting factor, at least when the cells are growing slowly. We have also shown that BY2 cells produce their own expansins, and we have cloned six α-expansin cDNAs from a BY2 library. Tobacco α-expansins have high sequence similarity to Arabidopsis and cucumber α-expansins. Addition of the tobacco sequences to the phylogenetic tree indicates that there are at least four groups of α-expansins. Previous work from our laboratory has shown that α-expansins are part of an ancient gene family, hinting that they are central to plant cell growth. Having established that expansins do play a role in the growth of suspension cultures, we are now in a position to begin to test directly how essential a mechanism they provide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Simon Gilroy for help with cell imaging, Dr. Richard Cyr for the BY2 cell lines, Dr. Lee McIntosh (Michigan State University) for the gift of the BY2 cDNA library, Dr. Mark Guiltinan for advice on screening the cDNA library, Daniel M. Durachko and Melva Perich for technical assistance, Jennie Hay for help with phylogenetics, and Mark Shieh and Tatyana Shcherban for many helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akehurst BC (1970) The botany, genetics and the development of commercial types. In D Rhind, ed, Tobacco, Ed 2. Longham Group, London, pp 42–61

- Cabot EL, Beckenbach AT. Simultaneous editing of multiple nucleic acid and protein sequences with ESEE. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:233–234. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HT, Kende H. Expression of expansin genes is correlated with growth in deepwater rice. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1661–1671. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Wall relaxation and the driving forces for cell expansive growth. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:561–564. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Characterization of long-term extension of isolated cell walls from growing cucumber hypocotyls. Planta. 1989;177:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Plant cell enlargement and the action of expansins. BioEssays. 1996;18:533–540. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ, Bedinger P, Durachko DM. Group I allergens of grass pollen as cell wall-loosening agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6559–6564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkes NR, Henrissat B, Kilburn DG, Miller RC, Warren RAJ. Domains of microbial β-1,4-glucanases: sequence conservation, function, and enzyme families. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:303–315. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.303-315.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager A, Menzel H, Krauss A. Versuche und Hypothese zur Primaerwirkung des Auxins beim Streckungswachstum. Planta. 1971;100:47–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00386886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrik N, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller E, Cosgrove DJ. Expansins in growing tomato leaves. Plant J. 1995;8:795–802. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.8060795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Koichiro T, Nei M (1993) MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 1.01. The Pennsylvania State University, University Park

- Kutschera U. The current status of the acid growth theory. New Phytol. 1994;126:549–569. [Google Scholar]

- Kutschera U, Schopfer P. Evidence for the acid-growth theory of fusicoccin action. Planta. 1985;163:494–499. doi: 10.1007/BF00392706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z-C, Durachko DM, Cosgrove DJ. An oat coleoptile wall protein that induces wall extension in vitro and that is antigenically related to a similar protein from cucumber hypocotyls. Planta. 1993;191:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Marré E. Fusicoccin: a tool in plant physiology. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1979;20:273–288. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil M, Darvill AG, Fry SC, Albersheim P. Structure and function of the primary cell walls of plants. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:625–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason S, Cosgrove DJ. Expansin mode of action on cell walls. Analysis of wall hydrolysis, stress relaxation, and binding. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:87–100. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason S, Durachko DM, Cosgrove DJ. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall expansion in plants. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1425–1433. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.11.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael AJ. A cDNA from pea petals with sequence similarity to pollen allergen, cytokinin-induced and genetic tumour-specific genes: identification of a new family of related sequences. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:219–224. doi: 10.1007/BF00017818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Takabe I, Matsui C. Delivery of tobacco mosaic virus RNA into plant protoplasts mediated by reverse-phase evaporation vesicles (liposomes) Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Nesius KK, Fletcher JS. Carbon dioxide and pH requirements of non-photosynthetic tissue culture cells. Physiol Plant. 1973;28:259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Poole DM, Hazlewood GP, Huskisson NS, Virden R, Gilbert HJ. The role of conserved tryptophan residues in the interaction of a bacterial cellulose binding domain with its ligand. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;80:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayle DL, Cleland RE. The acid growth theory of auxin-induced cell elongation is alive and well. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1271–1274. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AW, Haigler CH. Cell expansion and tracheary element differentiation are regulated by extracellular pH in mesophyll cultures of Zinnia elegans L. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:699–706. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JK, Lee HH, Bennet AB. Expression of a divergent expansin gene is fruit-specific and ripening-regulated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5955–5960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. DNA sequencing. In: Ford N, Nolan C, Ferguson M, editors. Molecular Cloning, Ed 2, Vol 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 13.2–13.104. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherban TY, Shi J, Durachko DM, Guiltinan MJ, McQueen-Mason S, Shieh M, Cosgrove DJ. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of expansins: a highly conserved, multigene family of proteins that mediate cell wall extension in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9245–9249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Krikorian AD. Low external pH prevents cell elongation but not multiplication of embryogenic carrot cells. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:459–501. [Google Scholar]

- Vanlerberghe GC, McIntosh L. Mitochondrial electron transport regulation of nuclear gene expression. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:867–874. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Sharp RE, Durachko DM, Cosgrove DJ. Growth maintenance of the maize primary root at low water potentials involves increases in cell wall extensibility, expansin activity, and wall susceptibility to expansins. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:765–772. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]