Abstract

Purpose

Factors that support self-efficacy must be understood in order to foster family-centered care (FCC) during rounds. Based on social cognitive theory, this study examined (1) how 3 supportive experiences (observing role models, having mastery experiences, and receiving feedback) influence self-efficacy with FCC during rounds and (2) whether the influence of these supportive experiences was mediated by self-efficacy with 3 key FCC tasks (relationship building, exchanging information, and decision making).

Method

Researchers surveyed 184 students during pediatric clerkship rotations during the 2008–2011 academic years. Surveys assessed supportive experiences and students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds and with key FCC tasks. Measurement models were constructed via exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Composite indicator structural equation (CISE) models evaluated whether supportive experiences influenced self-efficacy with FCC during rounds and whether self-efficacy with key FCC tasks mediated any such influences.

Results

Researchers obtained surveys from 172 eligible students who were 76% (130) White and 53% (91) female. Observing role models and having mastery experiences supported self-efficacy with FCC during rounds (each p<0.01), while receiving feedback did not. Self-efficacy with two specific FCC tasks, relationship building and decision making (each p < 0.05), mediated the effects of these two supportive experiences on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds.

Conclusions

Observing role models and having mastery experiences foster students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, operating through self-efficacy with key FCC tasks. Results suggest the importance of helping students gain self-efficacy in key FCC tasks before the rounds experience and helping educators implement supportive experiences during rounds.

Family-centered care (FCC) strives to engage families in three key tasks of a healthcare visit -- building relationships with care providers, exchanging information, and deliberating about decisions.1 The benefits of FCC include improved resource utilization, as well as increased patient and staff satisfaction.2–4 Training in FCC is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for all learners.5–7 To facilitate FCC, the AAP recommends conducting rounds at the bedside with the family present,5 so-called family-centered rounds. During these rounds, students may acquire FCC skills by observing and practicing communication skills and by observing models of professionalism and bedside manner.5,8–11 However, learner experiences with family-centered rounds aren’t always positive,12–16 and no formal curricula for teaching this rounding technique exist. To facilitate the learning process during family-centered rounds and students’ implementation of a FCC approach, it is imperative to understand factors that may influence medical students’ adoption of FCC during rounds.

Social cognitive theory (SCT) provides a useful framework for understanding mechanisms that may impact students’ behaviors during family-centered rounds.17 SCT posits that knowledge and skills alone are not always good predictors of behavior because the beliefs that an individual possess about her/his capabilities significantly affect behavior. Thus, self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s beliefs about her/his capabilities to organize and execute a behavior, is an important prerequisite.18 Bandura proposes several experiences that can support self-efficacy: (1) observing role models performing the behavior, (2) having opportunities to practice the behavior (mastery experiences), and (3) receiving feedback on one’s performance.19 Further, self-efficacy is context specific; thus, self-efficacy with FCC during rounds must be measured in that context. For medical students, the third-year clerkships often represents their first clinical experience with numerous stressors present.8,20,21 For example, many students experience difficulty with prioritizing competing demands and managing time, as well as coping with the emotional intensity of caring for patients.22,23 Students also encounter situational stressors such as personal problems (e.g., change in health status for themselves or loved ones),23 detection of medical errors, or tension among care teams.24 These stressors disrupt students’ abilities to implement a patient-centered approach.25

Identifying the factors that support students’ self-efficacy with FCC during family-centered rounds and the mechanisms through which these supports act informs the development of curricula. Guided by SCT, we hypothesize that medical students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds will be fostered by supportive experiences including observing role models, having mastery experiences, and receiving feedback. We also anticipate that the effects of supportive experiences on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds will be mediated by medical students’ self-efficacy with key FCC tasks (relationship building, exchanging information, and decision-making).

Method

Study context, participants, and procedures

During 17 pediatric clerkship rotations during the 2008–2011 academic years, 184 students experienced 3-week blocks of inpatient care at our 88-bed, free standing children’s hospital affiliated with a large, mid-western academic medical center. During this experience, the faculty members (primarily hospitalists) round with the multidisciplinary care team at the bedside with the family unless precluded by family preference. The care team typically includes an attending, a senior resident, two interns, up to 4 medical students, the patient’s nurse, and other care team members as appropriate (e.g., social worker or respiratory therapist). Family-centered rounds are conducted similarly across the pediatric clerkships with students presenting up to 4 patients under their care each day. The rounds contain a presentation of the patient’s diagnosis, progress, and care plan as well as bedside teaching and the opportunity for the team or family to raise questions or concerns. The institution has routinely conducted family-centered rounds since 2007 with limited formal training of attending physicians, residents, nurses, or medical students. The pediatric clerkship represents the only consistent opportunity for students to participate in family-centered rounds during their medical school training.

To develop measures and respond to our study’s research questions, we administered pre-and post-clerkship surveys assessing self-efficacy with FCC during rounds in the clinical setting, self-efficacy with FCC tasks, and supportive experiences to students experiencing these rounds. The study received approval from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. Completion of the survey provided implied consent.

Survey items

To generate items for each measure, we gathered potential items from the literature, pilot tested with students and faculty, and iteratively revised. The outcome of interest was self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, representing the student’s belief that she/he can successfully provide FCC during rounds on the pediatric inpatient service. Recognizing that medical students in the clinical setting experience many stressors that can impede self-efficacy with patient-centered care, we developed 11 items assessing self-efficacy with FCC during rounds while under various stressors of the clinical environment. Relevant literature and interviews with medical students informed identification of these stressors.8,20–25 Examples include fatigue, personal problems, and tensions among care team members. Students reported self-efficacy on these items using a 7-point scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree).

To assess supportive experiences (observing role models, having mastery experiences, and receiving feedback) of medical students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, we adapted items from the Cook County Inpatient Attending Evaluation or based on SCT.19,26 We measured all 19 items on a frequency-based, 5-point scale (1=never; 5=always).

To develop items to assess self-efficacy with FCC tasks, we began from the definition of FCC. Specifically, FCC is care that builds a relationship between providers and families, optimizes sharing of information, and includes families in decision making so that decisions reflect their values and preferences.27 Thus, self-efficacy items focused on 3 specific FCC tasks–building a relationship with families (4 items), exchanging information with families (3 items), and engaging families in decision making (4 items) during family-centered rounds. We adapted items representing these domains from either the Health Care Climate Questionnaire (HCCQ) or the Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale.28,29

In addition, all students provided information about their age (<30 vs. ≥30 years), gender, and ethnicity (White, Hispanic/Latino, African American/Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian/Pacific Islander or Other) and previously completed core clerkships (Psychiatry, Medicine, Surgery, Primary Care, Obstetrics/Gynecology).

Validation of measures

Pre-clerkship data informed our development and evaluation of scales to measure self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, supportive experiences, and self-efficacy with FCC key tasks. We used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine underlying constructs within self-efficacy with FCC during rounds and within supportive experiences. We assessed factor solutions with Eigenvalues followed by model fit indices using standard criteria for χ2 ratio, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI).30 To ensure measurement models derived from pre-clerkship responses are appropriate post-clerkship, tau equivalence of all models was established from pre to post-clerkship.

For medical students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, EFA yielded a 2-factor solution (eigenvalues of 6.15 and 1.00), with good model fit (χ2 ratio = 5.62, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.06). Three items loaded on Factor 1 (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) and 8 items loaded on Factor 2 (Cronbach’s α = 0.86). Items and factor loadings are presented in Table 1. Factor loadings indicate the extent to which the domain covaries with the indicator items. Factor 1’s indicators reflected “everyday stressors” that students encounter during clinical clerkships, while Factor 2’s indicators reflected “situational stressors” that arise from specific events or at specific times.

Table 1.

Factor loadings for indicators of self-efficacy with family-centered care during rounds (n=172)*

| Unstandardized† (s.e.)

|

Standardized‡

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy under everyday stressors | ||

| When there is time pressure, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.91 (0.03) | 0.87 |

| When I am stressed, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.98 (0.02) | 0.94 |

| When I am tired, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.96 |

| Self-efficacy under situational stressors | ||

| When other team members do not support family-centered care, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.69 (0.06) | 0.55 |

| When it is time to go to lunch, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.81 (0.05) | 0.65 |

| When there is tension between the primary team and consultants, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.86 (0.05) | 0.69 |

| When the healthcare team has made a mistake, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.89 (0.05) | 0.72 |

| When patients and families are given bad news, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 0.91 (0.05) | 0.73 |

| When families are difficult, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.81 |

| During or after experiencing personal problems, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 1.02 (0.04) | 0.82 |

| When I am feeling nervous, I can provide family-centered care during bedside rounds. | 1.05 (0.04) | 0.84 |

All indicators on a scale of 1=Strongly Disagree to 7=Strongly Agree

Unstandardized factor loadings are on the original item scale, reflecting the extent to which the domain covaries with the indicator item

Standardized factor loadings reflect the extent to which the domain is correlated with the indicator item

The base item in the scale with a fixed value of 1.00 is indicated with ---

With regard to the supportive experiences, EFA identified a three-factor model (eigenvalues of 10.32, 1.87, and 1.15) using 18 of the 19 indicators with good model fit (χ2 ratio = 3.23, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.05). Factor 1’s indicators reflected observing role models (Cronbach’s α = 0.92), Factor 2’s reflected having mastery experiences (Cronbach’s α = 0.85), and Factor 3’s reflected receiving feedback (Cronbach’s α = 0.92). One item did not load on any of the three factors and was dropped. Items and factor loadings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factor loadings for indicators of supportive experiences (n=172)*

| Unstandardized† (s.e.)

|

Standardized‡

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Observing role models | ||

| Attending physicians treated patients and families with respect. | 0.91 (0.07) | 0.70 |

| I learned how to provide family-centered care by observing attending physicians and/or senior residents model how to interact with patients and families during family-centered bedside rounds. | 0.99 (0.06) | 0.75 |

| The care team conducted family-centered bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.76 |

| Attending physicians were sensitive to the emotional, economic, social, and cultural aspects of patients’ illnesses. | 1.00 (0.06) | 0.76 |

| The care team provided family-centered care. | 1.07 (0.04) | 0.82 |

| Attending physicians modeled incorporating the best evidence from the literature with the unique circumstances and preferences of patients and families. | 1.07 (0.06) | 0.81 |

| During family-centered bedside rounds, the attending and/or senior resident was explicit about his/her reasoning when discussing clinical decisions with patients and families. | 1.09 (0.05) | 0.83 |

| During family-centered bedside rounds, the attending physician and/or senior resident was explicit about his/her reasoning when discussing clinical decisions with the care team. | 1.10 (0.05) | 0.84 |

| Mastery experiences | ||

| Attending physicians encouraged me to be an active decision-maker in patient care. | 0.97 (0.06) | 0.71 |

| Teaching sessions (i.e. at least 5 minutes devoted to education) with the team and the attending took place during family-centered bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.74 |

| Attending physicians expected me to incorporate the best evidence from the literature with the unique circumstances and preferences of patients and families. | 1.05 (0.06) | 0.77 |

| Attending physicians encouraged me to consider patients and families as active decision-makers in their care. | 1.05 (0.06) | 0.77 |

| I was successful in my attempts to provide family-centered care. | 1.19 (0.05) | 0.88 |

| Feedback | ||

| I received feedback from attending physicians and/or residents about my ability to communicate information to patients and families. | ---§ | 0.74 |

| I received feedback from attending physicians and/or residents about my ability to engage patients and families in the decision-making process about their care. | 1.13 (0.05) | 0.84 |

| I received feedback from attending physicians and/or residents about my ability to build relationships with patients and families. | 1.16 (0.06) | 0.86 |

| I received constructive criticism from attending physicians and/or residents about my performance on family-centered bedside rounds. | 1.30 (0.06) | 0.97 |

| I received positive feedback from attending physicians and/or residents about my performance on family-centered bedside rounds. | 1.32 (0.07) | 0.98 |

All indicators on a scale of 1=Never, 2=Rarely, 3=Occasionally, 4=Usually, 5=Always

Unstandardized factor loadings are on the original item scale, reflecting the extent to which the domain covaries with the indicator item

Standardized factor loadings reflect the extent to which the domain is correlated with the indicator item

The base item in the scale with a fixed value of 1.00 is indicated with ---

Indicators for self-efficacy with key FCC tasks were based on a 3-factor conceptual model of FCC, so we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), again using standard model fit criteria. CFA supported the 3-factor conceptual model of key tasks self-efficacy: building a relationship with families (Cronbach’s α = 0.88), exchanging information with families (Cronbach’s α = 0.76), and engaging families in decision making (Cronbach’s α = 0.90). Specifically, χ2 ratio = 3.6, CFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.896, SRMR = 0.05. Items and factor loadings are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Factor loadings for indicators of self-efficacy with key FCC tasks during rounds (n=172)*

| Unstandardized† (s.e.)

|

Standardized‡

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Building a relationship with the family | ||

| I can handle patient and family emotions during family-centered bedside rounds. | 0.73 (0.07) | 0.70 |

| I can be open with patients and families during family-centered bedside rounds. | 0.93 (0.07) | 0.79 |

| I can build trust with patients and families during family-centered bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.84 |

| I can encourage patients and families to share their feelings during family-centered bedside rounds. | 1.05 (0.07) | 0.86 |

| Exchanging information with the family | ||

| I can answer patient and family questions fully and carefully during family-centered bedside rounds. | 0.97 (0.12) | 0.61 |

| I can explain patients’ conditions and what they need to do in easily understandable terms during family-centered bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.73 |

| I can encourage patients and families to ask questions during family-centered bedside rounds. | 1.13 (0.11) | 0.78 |

| Engaging families in decision making | ||

| I can provide patients and families with choices and options during family-centered bedside rounds. | ---§ | 0.65 |

| During family-centered bedside rounds, I can listen to how patients and families would like to do things. | 1.29 (0.13) | 0.88 |

| I can involve patients and families in the decision-making process during family-centered bedside rounds. | 1.30 (0.13) | 0.89 |

| During family-centered bedside rounds, I can try to understand how patients and families see things before suggesting a new way to do things. | 1.31 (0.13) | 0.93 |

All indicators on a scale of 1=Strongly Disagree to 7=Strongly Agree

Unstandardized factor loadings are on the original item scale, reflecting the extent to which the domain covaries with the indicator item

Standardized factor loadings reflect the extent to which the domain is correlated with the indicator item

The base item in the scale with a fixed value of 1.00 is indicated with ---

Analyses

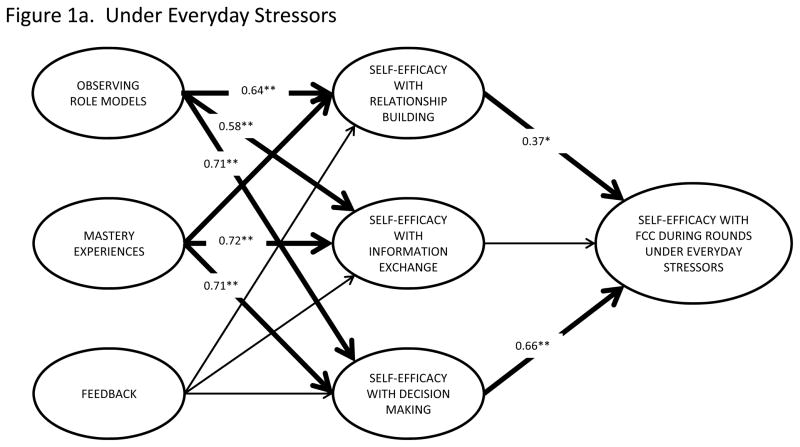

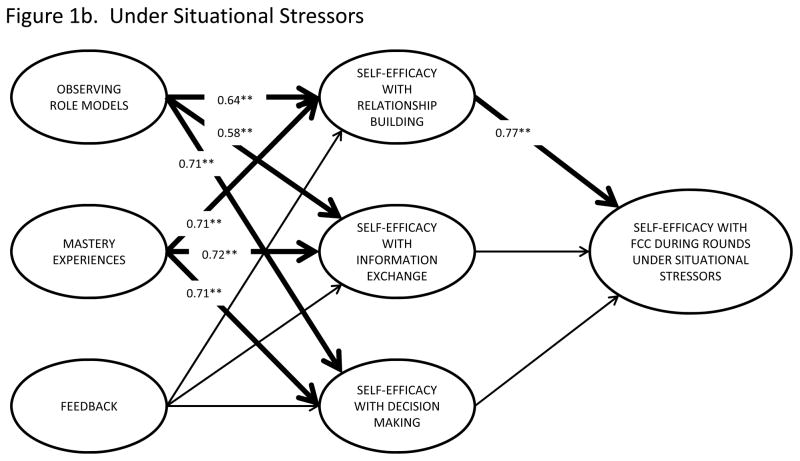

We used means with standard errors (se) and proportions to describe our students. To evaluate (1) the relationships between supportive experiences and self-efficacy with FCC during rounds and (2) whether the association between supportive experiences and self-efficacy during rounds is mediated through self-efficacy with key FCC tasks, we used composite indicator structural equation (CISE) models. (Figure 1) CISE modeling, in which the measurement error for the composite indicator is fixed based on reliability estimates, provides a valid method of addressing measurement error that arises in multiple regression.31 Results are presented as path coefficients with p values where significant. Path coefficients represent the direction and magnitude of the relationships between variables. We regarded a two-tailed p<0.05 as significant.

Figure 1.

Unstandardized Path Coefficientsa for the Mediation of the Influences of Supportive Experiences on Self-efficacy with Family-Centered Care (FCC) during Rounds by Self-efficacy with Key FCC Tasks

aFor ease of reading, Figure 1 displays model results for the two outcomes of interest separately and omits indicator items, error terms, correlations between latent constructs, and the nonsignificant direct influences of supportive experiences on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds. Parameter estimates for all terms in the model are available from the authors. Bolded paths are significant (*p<0.05; **p<0.001).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Of 184 pediatric clerkship students, 93% (172) provided pre-clerkship data while 88% (162) provided post-clerkship data. Students were 53% (91) female, 24% (42) from racial/ethnic minorities, 11% (19) at least 30 years of age, and varied considerably in their prior clerkship experiences, as expected when surveying medical students at different points in their third year. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Student characteristics (n=172)*

| n (%)

|

|

|---|---|

| Age (30 years or older) | 18 (11%) |

| Female | 90 (53%) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 129 (77%) |

| Number of Clerkships completed† | |

| 0 | 21 (13%) |

| 1 | 26 (16%) |

| 2 | 31 (19%) |

| 3 | 26 (16%) |

| 4 | 35 (21%) |

| 5 | 10 (15%) |

Values may not add to total or to 100% due to missing data or rounding

One student self-identified in two groups

Hypothesis 1: Supportive Experiences Foster Self-efficacy with FCC during Rounds

Two of the three supportive experiences (observing role models and having mastery experiences) predicted students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds under both everyday and situational stresses, while feedback had no significant influence. Specifically, the total effects revealed observing role models (path coefficient = 0.67, P < 0.01) and mastery experiences (path coefficient = 0.72, P < 0.01) supported self-efficacy with FCC during rounds under everyday stress. Similarly, observing role models (path coefficient = 0.55, P < 0.01) and having mastery experiences (path coefficient = 0.64, P < 0.01) supported self-efficacy with FCC during rounds under situational stress.

Hypothesis 2: Key FCC Tasks Mediate Supportive Experiences Impact on Self-Efficacy with FCC during Rounds

We then examined the effects of the supportive experiences to see if they directly affected self-efficacy with FCC during rounds or operated through self-efficacy with key FCC tasks. None of the supportive experiences directly influenced self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, but all operated through their effect on self-efficacy with key FCC tasks. The effects of observing role models on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds under everyday stressors were mediated by self-efficacy with two specific FCC tasks--building a relationship with families (indirect path coefficient = 0.24, P < 0.05) and engaging families in decision making (indirect path coefficient = 0.47, P < 0.01). The effects of having mastery experiences also were mediated by self-efficacy with building a relationship with families (indirect path coefficient = 0.27, P < 0.05) and self-efficacy with engaging families in decision making (indirect path coefficient = 0.47, P < 0.01). Indirect path coefficients are products of the direct effects of (1) supportive experiences on self-efficacy with key FCC task and (2) self-efficacy with key FCC task on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds. (Figure 1a)

With regard to self-efficacy with FCC during rounds under situational stressors, self-efficacy with relationship building mediated the positive effects of both supportive experiences--observing role models (indirect path regression coefficient = 0.49, P < 0.01) and having mastery experiences (indirect path regression coefficient = 0.55, P < 0.01). Feedback had no significant direct or indirect effects on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds under everyday or situational stressors. (Figure 1b)

Discussion

In order to facilitate the adoption of a family-centered approach to care, it is not only important to educate learners about FCC, but to bolster their self-efficacy to deliver FCC as it occurs –in the clinical setting. Findings shed light on factors that support learner self-efficacy with FCC during rounds, highlighting the contributions of observing role models and having mastery experiences to learners’ self-efficacy. Students’ self-efficacy, however, was not related to attending/resident feedback regarding their performance. Further, the effects of the supportive experiences’ on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds in the clinical setting were mediated by self-efficacy with key FCC tasks.

Students often have identified exposure to role models as critical to developing their communication skills and professional bedside manner, even during the pre-clinical curriculum.32–35 Harrell et al also found a strong positive relationship between the mastery opportunities afforded in hands-on clinical opportunities and students’ confidence in caring for patients.36 This observation is the basis for much of today’s movement toward simulation-based education. For example, students who had more opportunities to observe and take part in discussions with patients about difficult news, wishes and values had a greater sense of preparedness to provide end-of-life care.37 Thus, allowing students opportunity to observe and practice skills is critical to their self-efficacy with FCC, and may be operationalized through simulation of care as it occurs in the clinical setting as has been done for other communication skills.38–41 In addition, these supportive experiences are congruent with the ACGME and American Board of Medical Specialties’ move toward competency-based medical education in that they are learner-centered, formative experiences faculty do with the learners rather than to the learners.42–44

Contrary to generally hypothesized positive influences of feedback on self-efficacy, feedback given to students about their performance during rounds did not impact their self-efficacy with FCC during rounds. Moreover, this finding is inconsistent with recent literature about the role of feedback in shaping medical students’ confidence in their abilities to care for patients45,46 and to the value students place on feedback in developing their communication skills, especially at the bedside.47 At least three plausible explanations for this finding arise from the evidence base about feedback. First, the manner in which feedback is given could hinder self-efficacy.48 According to Bandura, feedback that is framed in terms of short-falls is apt to weaken self-efficacy by highlighting one’s deficiencies.19 Using a competency-based approach, i.e., advising learners of the steps needed to advance in their development to be competent, rather than focusing on achievement of the final step, could reframe feedback on performance during family-centered rounds in a more positive light.

Second, the timing of the feedback may have undermined self-efficacy. One of the common concerns of trainees about family-centered rounds is being corrected in front of families.12–16 Thus, if residents or faculty delivered negative feedback during rounds, this may have weakened self-efficacy. Third, students report faculty and resident expectations of their performance during family-centered rounds are unclear.12 In recent interviews about family-centered rounds experiences (unpublished work) students noted that unclear or inconsistent expectations across attendings and residents can lead to unexpected negative feedback. Specifically, one student noted how she had been asked to eliminate medical jargon while presenting during family-centered rounds only to receive negative feedback at a later time, suggesting she “needs to learn and apply the language of medicine.” For these reasons, faculty (and resident) development regarding family-centered rounds might focus on helping team leaders to articulate a clear, uniform progression of competencies for rounds and to base private, constructive feedback on this progression.49

The impact of supportive experiences on self-efficacy with FCC during rounds was mediated by self-efficacy with key FCC tasks. The Dreyfus model of skill acquisition suggests learners advance through the developmental stages as they gain a sense of competence and experience, ultimately enabling them to perform tasks under varying conditions such as the stressors of clinical practice.50 We find that learners’ self-efficacy with FCC in the clinical setting operates through their self-efficacy with specific FCC tasks, highlighting the importance of developing basic FCC skills before expecting students to succeed during family-centered rounds. Students learning basic techniques for interacting with patients during the first and second year of medical school might benefit from an introduction to key FCC tasks, followed by opportunities to apply these skills during clinical years. This approach also would foster the acceptance of family-centered rounds as a model for inpatient care across all physician specialties.

This study has limitations that should be considered. First, students’ reports of their experiences with family-centered rounds may be subject to recall bias and not reflective of actual occurrences. These reports could be validated by seeking data from other sources such as recordings of rounding sessions or even the perceptions of families or other healthcare team members. Second, family-centered rounding is a relatively new model at our institution. Although our attendings and residents have been providing family-centered rounds consistently for nearly 4 years and many have received formal training about teaching during bedside rounds, students’ experiences may reflect the challenges of this new process. However, this model is new to many institutions, suggesting many students may have experiences similar to those of our students.51 Lastly, generalizability to other student populations is not demonstrated, although our findings parallel those of prior studies as discussed and our students are similar to those of medical schools nationally.52,53

In summary, we find that medical students’ self-efficacy with FCC during rounds is fostered by observing role models and having mastery experiences, both of which operate through self-efficacy with key FCC tasks. Feedback, often considered a key self-efficacy support and highly valued by learners at the bedside and for developing communication skills47 did not foster FCC self-efficacy for these students. Educators might consider providing exposure to FCC early in medical student education and implementing faculty development sessions centered on FCC during rounds.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the gracious participation of our medical students and the support of our clerkship staff.

Funding/Support: The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the UW Department of Pediatrics Research and Development Fund and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation to Dr. Cox.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval has been granted from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Health Sciences Institutional Review Board for studies involving human subjects (Protocol number: M-2008-1232).

Disclaimer: None.

Previous presentations: None.

Contributor Information

Dr. Henry N. Young, University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy.

Dr. Jayna B. Schumacher, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Megan A. Moreno, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Dr. Roger L. Brown, Research Design and Statistics Unit, University of Wisconsin School of Nursing.

Dr. Ted D. Sigrest, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Gwen K. McIntosh, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Dr. Daniel J. Schumacher, Emergency Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Michelle M. Kelly, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Dr. Elizabeth D. Cox, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

- 1.Bird J, Cohen-Cole SA. The three-function model of the medical interview. An educational device. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. 1990;20:65–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solberg B. Wisconsin prenatal care coordination proves its worth. Case management becomes Medicaid benefit. Preventive Medicine. 1996;2(1):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammentorp J, Mainz J, Sabroe S. Parents’ priorities and satisfaction with acute pediatric care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005 Feb;159(2):127–131. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Keefe M, Sawyer M, Roberton D. Medical student interviewing skills and mother-reported satisfaction and recall. Medical Education. 2001;35(7):637–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003 Sep;112(3):691–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics. [Accessed November 13, 2011];Pediatrics Program Requirements. 2007 http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/320_pediatrics_07012007.pdf.

- 7.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. [Accessed November 13, 2011];The Joint Commission 2009 Requirements Related to the Provision of Culturally Competent Patient-Centered Care Hospital Accreditation Program (HAP) 2009 http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2009_CLASRelatedStandardsHAP.pdf.

- 8.Rogers HD, Carline JD, Paauw DS. Examination room presentations in general internal medicine clinic: Patients’ and students’ perceptions. Academic Medicine. 2003 Sep;78(9):945–949. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200309000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramani S, Orlander JD, Strunin L, Barber TW. Whither bedside teaching? A focus-group study of clinical teachers. Academic Medicine. 2003 Apr;78(4):384–390. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200304000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janicik RW, Fletcher KE. Teaching at the bedside: A new model. Medical Teacher. 2003 Mar;25(2):127–130. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000092490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janicik R, Kalet AL, Schwartz MD, Zabar S, Lipkin M. [Accessed November 13, 2011];Using Bedside Rounds to Teach Communication Skills in the Internal Medicine Clerkship. 2007 12:1–8. doi: 10.3402/meo.v12i.4458. http://med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/viewFile/4458/4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox ED, Schumacher JB, Young HN, Evans MD, Moreno MA, Sigrest TD. Academic Pediatrics. 2011. Dec 03, Medical student outcomes after family-centered bedside rounds; pp. 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landry MA, Lafrenaye S, Roy MC, Cyr C. A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference-room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007 Aug;120(2):275–280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: Medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2009 Apr-Jun;21(2):105–110. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron MA, Schleien CL, Morris MC. Parental presence on pediatric intensive care unit rounds. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009 Oct;155(4):522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams KN, Ramani S, Fraser B, Orlander JD. Improving bedside teaching: Findings from a focus group study of learners. Academic Medicine. 2008 Mar;83(3):257–264. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181637f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Social cognitive mechanisms. In: Benson L, editor. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. pp. 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist. 1982;37(2):122–147. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moss F, McManus IC. The anxieties of new clinical students. Medical Education. 1992 Jan;26(1):17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosley TH, Jr, Perrin SG, Neral SM, Dubbert PM, Grothues CA, Pinto BM. Stress, coping, and well-being among third-year medical students. Academic Medicine. 1994 Sep;69(9):765–767. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199409000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien B, Cooke M, Irby DM. Perceptions and attributions of third-year student struggles in clerkships: Do students and clerkship directors agree? Academic Medicine. 2007 Oct;82(10):970–978. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31814a4fd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Academic Medicine. 2006 Apr;81(4):354–373. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiggleton C, Petrusa E, Loomis K, et al. Medical students’ experiences of moral distress: Development of a web-based survey. Academic Medicine. 2010 Jan;85(1):111–117. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c4782b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bombeke K, Symons L, Debaene L, De Winter B, Schol S, Van Royen P. Help, I’m losing patient-centredness! Experiences of medical students and their teachers. Medical Education. 2010 Jul;44(7):662–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CA, Varkey AB, Evans AT, Reilly BM. Evaluating the performance of inpatient attending physicians: A new instrument for today’s teaching hospitals. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004 Jul;19(7):766–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996 Jan;70(1):115–126. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf MH, Putnam SM, James SA, Stiles WB. The medical interview satisfaction scale: Development of a scale to measure patient perceptions of physician behavior. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1978 Dec;1(4):391–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00846695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998 Dec;3(4):424–453. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald RA, Behson SJ, Seifert CF. Strategies for dealing with measurement error in multiple regression. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics. 2005 Mar;5(3):80–97. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: Learning bedside manner from the experts. Academic Medicine. 2006 Jul;81(7):661–667. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232423.81299.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baernstein A, Oelschlager AM, Chang TA, Wenrich MD. Learning professionalism: Perspectives of preclinical medical students. Academic Medicine. 2009 May;84(5):574–581. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819f5f60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White CB, Kumagai AK, Ross PT, Fantone JC. A qualitative exploration of how the conflict between the formal and informal curriculum influences student values and behaviors. Academic Medicine. 2009 May;84(5):597–603. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fba36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murinson BB, Klick B, Haythornthwaite JA, Shochet R, Levine RB, Wright SM. Formative experiences of emerging physicians: Gauging the impact of events that occur during medical school. Academic Medicine. 2010 Aug;85(8):1331–1337. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e5d52a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrell PL, Kearl GW, Reed EL, Grigsby DG, Caudill TS. Medical students’ confidence and the characteristics of their clinical experiences in a primary care clerkship. Academic Medicine. 1993 Jul;68(7):577–579. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199307000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billings ME, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, Block S, Sullivan AM. Determinants of medical students’ perceived preparation to perform end-of-life care, quality of end-of-life care education, and attitudes toward end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010 Mar;13(3):319–326. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Losh DP, Mauksch LB, Arnold RW, et al. Teaching inpatient communication skills to medical students: An innovative strategy. Academic Medicine. 2005 Feb;80(2):118–124. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200502000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bokken L, Rethans JJ, Jobsis Q, Duvivier R, Scherpbier A, van der Vleuten C. Instructiveness of real patients and simulated patients in undergraduate medical education: A randomized experiment. Academic Medicine. 2010 Jan;85(1):148–154. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c48130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bokken L, Rethans JJ, van Heurn L, Duvivier R, Scherpbier A, van der Vleuten C. Students’ views on the use of real patients and simulated patients in undergraduate medical education. Academic Medicine. 2009 Jul;84(7):958–963. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a814a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kneebone R, Nestel D, Wetzel C, et al. The human face of simulation: Patient-focused simulation training. Academic Medicine. 2006 Oct;81(10):919–924. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238323.73623.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. Shifting paradigms: From Flexner to competencies. Academic Medicine. 2002 May;77(5):361–367. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hicks PJ, England R, Schumacher DJ, et al. Pediatrics milestone project: Next steps toward meaningful outcomes assessment. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2010 Dec;2(4):577–584. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00157.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carraccio C, Burke AE. Beyond competencies and milestones: Adding meaning through context. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2010 Sep;2(3):419–422. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00127.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hobgood CD, Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hollar DW, Jr, Sawning S. Griev_Ing: Death notification skills and applications for fourth-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2009 Jul;21(3):207–219. doi: 10.1080/10401330903018450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen W, Liao SC, Tsai CH, Huang CC, Lin CC. Clinical skills in final-year medical students: The relationship between self-reported confidence and direct observation by faculty or residents. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 2008 Jan;37(1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torre DM, Simpson D, Sebastian JL, Elnicki DM. Learning/feedback activities and high-quality teaching: Perceptions of third-year medical students during an inpatient rotation. Academic Medicine. 2005 Oct;80(10):950–954. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. Who wants feedback? An investigation of the variables influencing residents’ feedback-seeking behavior in relation to night shifts. Academic Medicine. 2009 Jul;84(7):910–917. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a858ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gigante J, Dell M, Sharkey A. Getting beyond “Good job”: How to give effective feedback. Pediatrics. 2011 Feb;127(2):205–207. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE. Mind Over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. New York, NY: Free Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, Gonzalez del Rey J, DeWitt TG. Family-centered bedside rounds: A new approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007 Apr;119(4):829–832. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed November 13, 2011];Table 6: Age of Applicants to U.S. Medical Schools at Anticipated Matriculation by Sex and Race and Ethnicity. 2010 https://www.aamc.org/download/159350/data/table9-facts2010age-web.pdf.pdf.

- 53.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed November 13, 2011];Table 29: Total U.S. Medical Schools Graduates by Race and Ethnicity Within Sex, 2002–2010. 2010 https://www.aamc.org/download/147312/data/table29-gradsraceeth0210_test2-web.pdf.pdf.