Abstract

Background

Previous studies have reported prefrontal cortex (PFC) pathophysiology in bipolar disorder.

Method

We examined the hemodynamics of the PFC during resting and cognitive tasks in 29 patients with bipolar disorder and 27 healthy controls, matched for age, verbal abilities and education. The cognitive test battery consisted of letter and category fluency (LF and CF), Sets A and B of the Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (RCPM-A and RCPM-B) and the letter cancellation test (LCT). The tissue oxygenation index (TOI), the ratio of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) concentration to total hemoglobin concentration, was measured in the bilateral PFC by spatially resolved near-infrared spectroscopy. Changes in HbO2 concentration were also measured.

Results

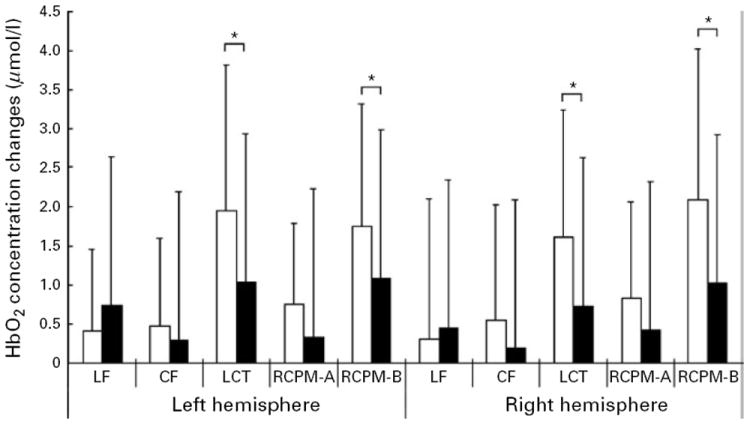

The bipolar group showed slight but significant impairment in performance for the non-verbal tasks (RCPM-A, RCPM-B and LCT), with no significant between-group differences for the two verbal tasks (LF and CF). A group × task × hemisphere analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the TOI revealed an abnormal pattern of prefrontal oxygenation across different types of cognitive processing in the bipolar group. Post hoc analyses following a group × task × hemisphere ANOVA on HbO2 concentration revealed that the bipolar group showed a greater increase in HbO2 concentration in the LCT and in RCPM-B, relative to controls.

Conclusions

Both indices of cortical activation (TOI and HbO2 concentration) indicated a discrepancy in the PFC function between verbal versus non-verbal processing, indicating task-specific abnormalities in the hemodynamic control of the PFC in bipolar disorder.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, near-infrared spectroscopy, prefrontal cortex, tissue hemoglobin saturation

Introduction

Whereas early efforts to uncover differences in cortical volume in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) did not reveal overall abnormalities (Pearlson et al. 1997), a recent study documented regional abnormalities in gray matter in several regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Lopez-Larson et al. 2002). Postmortem histopathologic studies have indicated reduced cell density in the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) (Rajkowska et al. 2001). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies using 1H-MRS have reported findings of deceased N-acetyl aspartate, considered a marker of neuronal integrity, in the PFC of BD patients (Sassi et al. 2005). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction is important for the pathophysiology of BD (Kato et al. 1993; Kato & Kato, 2000; Konradi et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2006). It is known that mitochondrial dysfunction increases anaerobic energy production and lactate production, and a recent study reported increased levels of gray-matter lactate in patients with BD (Dager et al. 2004). Collectively, these findings suggest subtle cytoarchitectural or neurophysiological abnormalities in the PFC of patients with BD.

Studies that employed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) reported abnormal PFC activity in patients with BD using various cognitive tasks, including verbal fluency (VF) (Curtis et al. 2001), the Stroop task (Blumberg et al. 2003), working memory (WM) (Adler et al. 2004; Monks et al. 2004) and the continuous performance test (Strakowski et al. 2004). Whereas one study reported a trait abnormality of blunted activation in the left ventral PFC in BD patients (Blumberg et al. 2003), several fMRI studies reported increased frontal signals during cognitive activation in euthymic (Adler et al. 2004; Strakowski et al. 2004) and manic BD patients (Blumberg et al. 2003), although one study observed reductions in bilateral frontal activation and increased activations with the left precentral, right medial frontal and left supramarginal gyri in BD patients during a two-back WM task (Monks et al. 2004). Results of these studies generally suggested abnormal regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) control in response to cognitive demands in BD. However, the findings were contradictory between studies in terms of hyper-/hypo-frontality, with a lack of the manipulation of cognitive demand, which makes it difficult to compare results.

A most recently developed non-invasive method of studying cerebral activation, transcranial near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) (Jobsis, 1977), utilizes optical technology to monitor cerebral oxygenation and hemodynamics (Jobsis, 1977). Continuous-wave NIRS systems utilizing differential spectroscopy can measure relative but quantitative changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) from baseline. This methodology has been used to assess PFC function in healthy adult subjects (Villringer et al. 1993; Fallgatter & Strik, 1998; Toichi et al. 2004; Kubota et al. 2006) and has been successfully utilized to demonstrate bilateral reduced frontal activation during a VF task in depressed patients (Herrmann et al. 2004), patients with schizophrenia (Kubota et al. 2005) and also in euthymic (Matsuo et al. 2002) and depressed (Kameyama et al. 2006) patients with BD. Furthermore, a recent fMRI/NIRS combination study observed functional asymmetry of prefrontal activation during a WM task in patients with schizophrenia (Lee et al. 2008). The concordance of fMRI and NIRS data supports NIRS as a useful functional neuroimaging method for psychiatric research.

Recent advances in NIRS technology have enabled absolute measurement of tissue oxygen saturation using a spatially resolved spectroscopy (SRS) system. In the present study, we used a two-channel SRS system (NIRO-300; Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan), which can measure the tissue oxygenation index (TOI), re-presented by the ratio of HbO2 concentration to total hemoglobin (HbT) concentration [i.e. HbO2 concentration + deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentration] in cerebral tissue. TOI has been used to monitor cortical oxygenation during neurosurgical intervention (Al-Rawi & Kirkpatrick, 2006). NIRO-300 enables the assessment of TOI every 2 s continuously for more than 1 h in an ordinary experimental room setting well tolerated by psychiatric patients; however, no study has investigated TOI changes during cognitive task performance in patients with BD.

The aim of the present NIRS study was to investigate PFC hemodynamics in adult patients with BD using a cognitive test battery, including a simple attention task as well as verbal- and non-verbal higher cognitive tasks. Previously, we have reported a specific pattern of PFC oxygenation in healthy subjects during the attention task. The observed oxygenation patterns were distinct from those typically observed during higher cognitive tasks, such as VF, suggestive of more excessive prefrontal oxygen consumption during attentional processing (Toichi et al. 2004). Based on this and a previous NIRS study reporting hypofrontality during VF in BD patients (Matsuo et al. 2004), we hypothesized that task-specific abnormal cortical oxygenation in the PFC of patients with BD might be detected by NIRS when contrasting attention versus higher cognitive tasks.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from the Mood Disorder Program, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Case Medical Center from April 2002 through March 2003. The inclusion criteria for patients with BD were the following: (1) patients aged 18–65 years (inclusive) who met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, which was confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (First et al. 2002) and assessment by a physician; (2) patients who were strongly right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971). The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with neurological disorders or brain injury; (2) patients who may have a general medical condition or neurological condition that may be considered the etiology of patients’ mood disorder; (3) patients who had a history within the past 6 months of substance abuse/dependence.

Inclusion criteria for comparison subjects were: (1) aged 18–65 years (inclusive); (2) subjects who did not have a history of psychiatric illness as assessed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al. 1998); (3) subjects who were strongly right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory. The University Hospitals of Cleveland Institutional Review Board for Human Investigation approved the protocol of this study.

Twenty-nine patients with BD (17 male, 12 female) and 27 healthy comparison subjects (15 male, 12 female) participated. All study participants provided written informed consent after the procedures had been fully described. The mood states and global functioning of the patients with BD were assessed by the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Asberg, 1979), the Young Mania Rating Scale (Young, 1978) and the Global Assessment Scale (Endicott et al. 1976). Clinical data of the BD patients are given in Table 1. The mean age of onset illness was 21.5 years (range 15–33 years) and the mean duration of illness was 18.8 years (range 2–42 years). Five of our patients with BD have a history of hospitalization, seven experienced psychotic episodes, 12 were rapid cyclers and 12 showed mixed state. The bipolar and comparison groups were matched for age [41.3 years (s.d.=11.0) years and 39.8 years (s.d.=14.1 years), respectively], for verbal abilities as assessed by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (Wechsler, 1981) [45.2 (s.d.=11.0) and 46.2 (s.d.=8.7), respectively] and for years of education [15.4 (s.d.=2.0) and 15.1 (s.d.=1.3), respectively; all t values <0.369, all p values >0.093). There was no difference in the gender ratio between groups (χ2, p=0.285).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects in the bipolar group

| Patient no. | Gender | Age | Scores

|

Daily dosages prescribed (mg)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS | YMRS | GAS | DVPX | Li | LTG | Other | |||

| 1 | F | 38 | 10 | 9 | 70 | 1250 | 1200 | 0 | |

| 2 | M | 52 | 10 | 3 | 70 | 500 | 450 | 0 | |

| 3 | F | 50 | 10 | 14 | 70 | 0 | 675 | 50 | |

| 4 | M | 46 | 9 | 1 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 300 | Olanzapine 10 |

| 5 | F | 55 | 6 | 2 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 100 | Clozapine 200 |

| 6 | F | 35 | 4 | 15 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 300 | Aripiprazole 15 |

| 7 | F | 62 | 2 | 2 | 90 | 0 | 300 | 100 | Venlafaxine 75 |

| 8 | M | 64 | 5 | 3 | 85 | 500 | 0 | 50 | Paroxetine 40 |

| 9 | M | 43 | 6 | 3 | 90 | 250 | 450 | 25 | |

| 10 | M | 39 | 0 | 5 | 90 | 500 | 600 | 0 | |

| 11 | F | 34 | 5 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 200 | Ziprasidone 80 |

| 12 | F | 36 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 1250 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | M | 36 | 2 | 5 | 85 | 250 | 450 | 0 | Bupropion 150 |

| 14 | M | 53 | 0 | 1 | 90 | 0 | 600 | 0 | Fluoxetine 20 |

| 15 | F | 47 | 4 | 1 | 90 | 0 | 900 | 150 | |

| 16 | M | 23 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | |

| 17 | M | 23 | 4 | 8 | 85 | 1750 | 1200 | 0 | |

| 18 | F | 30 | 5 | 2 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bupropion 300 |

| 19 | F | 30 | 0 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 900 | 300 | Sertraline 200 |

| 20 | F | 51 | 25 | 3 | 51 | 250 | 300 | 100 | |

| 21 | M | 32 | 23 | 6 | 51 | 1500 | 2250 | 0 | |

| 22 | F | 45 | 21 | 0 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 200 | Quetiapine 50 |

| 23 | F | 38 | 19 | 0 | 65 | 0 | 450 | 200 | Aripiprazole 10 |

| 24 | M | 46 | 16 | 5 | 65 | 250 | 450 | 0 | |

| 25 | F | 40 | 18 | 32 | 55 | 250 | 675 | 100 | |

| 26 | F | 47 | 23 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 900 | 0 | Quetiapine 150 |

| 27 | M | 42 | 15 | 7 | 61 | 2500 | 1500 | 200 | |

| 28 | F | 43 | 12 | 13 | 71 | 0 | 900 | 200 | Bupropion 300 |

| 29 | F | 19 | 18 | 10 | 65 | 1500 | 450 | 0 | |

F, Female; M, male; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; GAS, Global Assessment Scale; DVPX, divalproex sodium; Li, lithium carbonate; LTG, lamotorigine.

Cognitive tasks

Verbal tasks

Verbal tasks consisted of category and letter fluency tasks (CF and LF, respectively). Subjects were asked to generate as many words as possible that belonged to a given semantic category (‘vehicles’, ‘furniture’, ‘vegetables’, ‘metals’, ‘insects’ and ‘carpenter’s tools’ each for 15 s), or that began with a given letter (F, A, S, P, G, and R, each for 15 s). The baseline task was pronouncing the ‘da’ sound every 1 s (30 s), using a signal (an asterisk) that appeared on a computer display. The word fluency tasks have been known to activate the DLPFC (Curtis et al. 1998; Audenaert et al. 2000).

Non-verbal visual tasks

In Set A and Set B of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (Raven, 1962) (RCPM-A and RCPM-B, respectively), subjects were shown a figural pattern with a missing part, and then asked to select (by pointing) one of six alternatives that best completed the pattern. The items in Set A, which require only figural reasoning, are less difficult than the items in Set B that also require analytical (logical) reasoning. The order of the three sets was counterbalanced among subjects, and tasks were conducted at a self-paced rate. During the baseline task for RCPM, subjects had to choose between one of six figural patterns that was identical to the original pattern shown (30 s). The task was conducted using a booklet, and consisted of five items. In all subjects, RCPM was preceded by the baseline task. Short breaks (between the sets of RCPM or between the baseline task and RCPM) were given to subjects upon request. It has been confirmed that RCPM leads to activation of the DLPFC (Esposito et al. 1999).

Attention task

In the letter cancellation test (LCT), a typical task of attention, subjects were asked to cross out all the E’s and C’s in rows of letters in 60 s. In the baseline task, which preceded the LCT, subjects were instructed to cross out all the letters in rows of letters (a total of 30 letters) at a rate of one letter per s according to a digital sound. The baseline and main tasks were conducted successively without breaks.

Measurements

Hemodynamic changes in the PFC were measured by a two-channel NIRS system (NIRO 300; Hamamatsu Photonics, Shizuoka, Japan). A pair of optodes (a light emitter and a detector) was bilaterally attached to the forehead of a subject. A light detector was placed at the position of Fp1 and Fp2 according to the international 10–20 electrode system. A light emitter was placed 4 cm lateral to the corresponding emitter on the line that linked Fp1 to F7 or Fp2 to F8. The optode positioning procedure is detailed elsewhere (Toichi et al. 2004).

Changes in HbO2 concentration, HbR concentration and the TOI were measured using four different wave-lengths (775, 810, 870 and 904 nm) of near infrared light (Cope & Delpy, 1988). The cerebral tissue examined by NIRS is supposed to be a banana-shaped region between the two optodes (Gratton et al. 1994). By assuming the differential pathlength factor to be 6.0 (van der Zee et al. 1992; Duncan et al. 1995), the measure of change in HbO2 concentration and HbR concentration is considered to be expressed in μmol/l. On the other hand, TOI was measured by SRS, an NIRS method using the multi-distance approach that does not need the above-mentioned assumption of DPF (Matcher et al. 1995). The sampling frequency for measurements was every 2 s. Measurements took 30–40 min. All subjects were in a sitting position throughout all measurements.

Data analyses

In each subject, the average changes in HbO2 concentration and HbR concentration from the baseline were calculated for active task conditions (the first 10 s under each condition were excluded) for the word fluency tasks and the LCT. For RCPM, the average changes from the baseline during the performance of the last three correctly answered items in Set A and those of Set B was calculated (approximately 20 s each). The average TOI was calculated for baseline and task conditions. The TOI baseline value was computed by averaging the values of TOI during the period before each task for each subject (i.e. mean of the baseline before LF, CF, LCT and RCPMs).

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 11.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Unpaired t tests were used to compare performance in cognitive tasks between groups. Data were analysed using a group (bipolar, comparison) × hemisphere (left, right) × condition repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), using simple effects contrasts to compare the change in activation versus baseline for each subsequent task (LF, CF, RCPM-A, RCPM-B, LCT). Fisher’s least significant difference test was used for post hoc comparisons.

Results

Performance in cognitive tasks

The number of generated words for LF and CF was 33.2 (s.d.=8.4) and 32.8 (s.d.=7.3) in the bipolar group, and 36.9 (s.d.=9.3) and 36.5 (s.d.=7.4) in the comparison group, respectively. There were no differences in the performance of LF and CF between bipolar and comparison groups (t=1.54, df=54, p=0.129, for LF; t=1.92, df=54, p=0.061, for CF). Performance for RCPM-A (full score 12) and RCPM-B (full score 12) was 10.6 (s.d.=0.9) and 10.1 (s.d.=1.8) in the bipolar group, and 11.3 (s.d.=1.1) and 11.0 (s.d.=1.0) in the comparison group. The number of correct cancellations, commission errors and omission errors in the LCT was 49.3 (s.d.=10.9), 0.34 (s.d.=1.7) and 1.9 (s.d.=1.9) in the bipolar group, and 59.1 (s.d.=12.4), 0.0 (s.d.=0.0) and 1.3 (s.d.=1.6) in the comparison group. There were significant differences between the groups in the performance of RCPM-A (t=2.42, df=54, p=0.019, two-tailed), RCPM-B (t=2.30, df=54, p=0.025, two-tailed) and correct cancellation of the LCT (t=3.14, df=54, p=0.003, two-tailed).

Tissue hemoglobin saturation during rest and tasks

Group × task × hemisphere ANOVA on TOI yielded no significant main effect of group [F(1, 53)=0.081, p=0.777], task [F(1, 54)=0.494, p=0.781] or hemisphere [F(1, 54)=0.143, p=0.707]. There was a significant group × task interaction (F(5, 270)=2.528, p= 0.029], with no two-way interaction [F(5, 270)=0.186, p=0.968]. This indicated that the BD group and control group showed different patterns of TOI level change across the different cognitive tasks. There was also a task × hemisphere interaction [F(5, 270)=3.009, p=0.012], suggesting that left dominant activation was more prominent in verbal tasks. Post hoc simple effects comparisons on TOI revealed no significant main effect. This is because variations in the TOI value between individuals are relatively large compared with task-related effects (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Tissue hemoglobin saturation under baseline and task conditions for left and right hemispheres in patients with bipolar disorder (–◇–) and normal controls (–◆–). LF, Letter fluency task; CF, category fluency task; LCT, letter cancellation test; RCPM-A, Set A of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices; RCPM-B, Set B of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices. Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. Note that relatively large between-subject differences of tissue oxygenation index (TOI) are found in the baseline condition, which partly explained apparently large between-subjects differences in TOI increases.

In order to further investigate task-related abnormal hemodynamic responses in BD, a group × task × hemisphere ANOVA on the increase of TOI from the baseline (ΔTOI) was performed, which yielded no significant main effect of group [F(1, 54)=0.559, p=0.458], task [F(1, 54)=0.508, p=0.730] or hemisphere [F(1, 54)=0.768, p=0.385]. There was a significant group × task interaction [F(4, 216)=2.595, p= 0.037], with no two-way interaction [F(4, 216)=0.157, p=0.960]. Post hoc simple effects comparison on ΔTOI revealed that the BD group showed a significantly smaller increase for LF (p=0.004) and CF (p= 0.016) than the comparison group, with no significant difference for the LCT (p=0.191), RCPM-A (p=0.334) or RCPM-B (p=0.275). There was also a significant task × hemisphere interaction [F(4, 216)= 3.114, p=0.016]. Post hoc simple effects comparison revealed that participants, regardless of the diagnostic group, showed significantly increased left hemispheric activation in LF (p=0.048) and a trend of left dominant activation in CF (p=0.053) compared with the LCT. Together, these results indicate that the BD group showed lower levels of TOI, especially during verbal tasks (LF and CF), although their performance was not impaired.

In order to investigate the possible effect of mood states on the TOI level, additional analysis using a subgroup × task × hemisphere ANOVA was conducted to compare the two bipolar subgroups, i.e. the bipolar subgroup with modest but distinct depressive symptoms (n=19; MADRS, mean=19, range 12–25) and without depressive symptoms (n=10; MADRS, mean=4, range 0–10). There was no main effect for subgroup [F(1, 27)=1.04, p=0.317]. Subgroup also did not significantly interact with task [F(5, 135)=0.31, p=0.909], but there was a significant subgroup × hemisphere interaction [F(1, 27)=6.30, p=0.018), with no three-way interaction. This is because the depressive subgroup, relative to the euthymic subgroup, showed a significantly higher TOI in the left hemisphere during baseline (p=0.050) as well as the LCT (p=0.049) and RCPM-B (p=0.045).

Changes in hemoglobin concentration due to cognitive activation

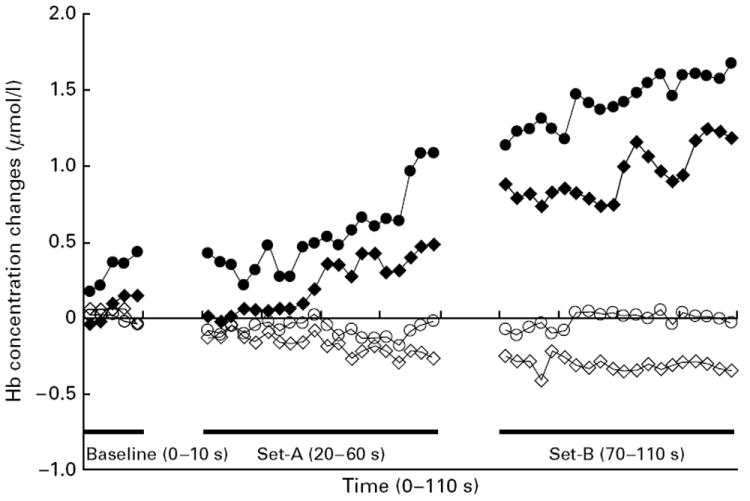

In most subjects, HbO2 concentration increased with a concurrent decrease in HbR concentration during activation in LF, CF, RCPM-A and RCPM-B, as shown in Fig. 2. In the attention task (LCT), on the other hand, both HbO2 concentration and HbR concentration increased. This finding is reported in our previous study that compared hemodynamic changes due to attention versus higher cognitive processing (Toichi et al. 2004).

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of mean oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentration changes in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) and normal controls for the left hemisphere. A bar above ‘Baseline’, ‘Set A’ and ‘Set B’ indicates the period during which the patient was performing the baseline task and Set A and Set B of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices. –●–, HbO2 concentration change for BD patients; –◆–, HbO2 concentration change for normal controls; –○–, HbR concentration change for BD patients; –◇–, HbR concentration change for normal controls.

A group × hemisphere × task ANOVA on HbO2 concentration revealed a significant main effect of task [F(4, 216)=12.296, p<0.001], but the main effect of hemisphere [F(1, 54)=0.513, p=0.477] was not significant. There was a non-significant trend of group effect [F(1, 54)=3.051, p=0.086], suggestive of relatively prominent HbO2 concentration increase in the BP group. There was significant group × task interaction [F(4, 216)=2.508, p=0.043), with no significant group × hemisphere [F(1, 54)=0.700, p=0.407), task × hemisphere interaction [F(4, 216)=1.770, p=0.136] or two-way interactions [F(4, 216)=0.363, p=0.835]. This again indicated that PFC oxygenation levels were different between the groups in a task-dependent manner (Fig. 3). Post hoc simple effects comparison revealed that BD patients showed a more prominent increase of HbO2 concentration compared with healthy controls in the LCT (p=0.001) and in RCPM-B (p=0.002), but not in LF (p=0.408), CF (p=0.332) and RCPM-A (p=0.129). These results indicate more prominent cortical oxygenation in the bipolar group, especially in the attention-demanding task (LCT) and the non-verbal higher cognitive task (RCPM-B), although their performance was compromised (Figs 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Changes from baseline in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) concentration due to cognitive tasks in patients with bipolar disorders (□) and normal controls (■). Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. LF, Letter fluency task; CF, category fluency task; LCT, letter cancellation test; RCPM-A, Set A of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices; RCPM-B, Set B of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices. * Post hoc analyses following a group × task × hemisphere analysis of variance on HbO2 concentration revealed that the bipolar disorder group showed a greater increase in HbO2 concentration in the LCT and in RCPM-B, relative to controls (p<0.005).

Fig. 4.

Changes from baseline in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentration due to cognitive tasks in patients with bipolar disorders (□) and normal controls (■). Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. LF, Letter fluency task; CF, category fluency task; LCT, letter cancellation test; RCPM-A, Set A of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices; RCPM-B, Set B of Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices. * Post hoc analysis following a group × task × hemisphere analysis of variance on HbR concentration revealed that both groups showed a greater increase in HbR concentration in the LCT compared with the other tasks (p<0.005). Note that the graph indicates net increases of Hb concentration from a baseline value (ΔHb concentration) and not changes in the absolute value of Hb concentration in the scanned region. ΔHb concentration showed modest increases by cognitive activation when compared with apparently large between-subjects differences of Hb

A group × hemisphere × task ANOVA on HbR concentration revealed a significant main effect of task [F(4, 216)=6.819, p<0.001], but the main effect of hemisphere [F(1, 54)=0.028, p=0.868] and group [F(1, 54)=0.069, p=0.794) was not significant. There were no significant interactions. Post hoc analysis indicated that subjects, regardless of the diagnostic group, showed a significantly increased HbR concentration in the LCT compared with an HbR concentration increase in LF (p<0.001), CF (p=0.001), RCPM-A (p<0.001) and RCPM-B (p<0.001) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, these data represent the first efforts to elucidate task-specific abnormal PFC oxygenation in patients with BD by using two hemodynamic parameters, TOI and HbO2, and multiple-task paradigms. No other imaging studies on BD have investigated prefrontal oxygenation across various cognitive task conditions, and the present finding of TOI, which was examined for the first time in BD patients, as well as that of HbO2 concentration, commonly indicated task-specific abnormality of PFC activation in subjects with BD.

During verbal processing requiring executive/WM components (LF and CF), comparison subjects showed clear cortical oxygenation, as indicated in TOI increase, with relatively moderate TOI increase during the simple attention task (LCT) or figural processing (RCPMs), which was in accordance with our previous finding (Toichi et al. 2004). On the other hand, the BD group showed relatively attenuated TOI increase during verbal processing, although performance was not significantly impaired. It has been demonstrated that TOI, corresponding to the ratio of HbO2 concentration to HbT concentration in cerebral tissue, is affected by changes in arterial blood supply. For example, a reduction in rCBF led to a decrease in HbO2 concentration with an increase in HbR concentration, resulting in a decrease in TOI (Kuroda et al. 1996; Krakow et al. 2000). That the result of atypical patterns of TOI changed across task conditions between groups suggested that rCBF control in the PFC of BD might be abnormally related to different cognitive demands.

The changes of HbO2 concentration also showed a task-specific atypical response in the BD group. During the LCT and RCPM-B, BD patients showed a greater HbO2 concentration increase when compared with healthy subjects. This is largely in line with a previous NIRS study reporting attenuated prefrontal activity during VF in BD (Kameyama et al. 2006). The observed abnormal hyperoxygenation in the BD patients during visual/attentional processing was not attributable to the performance level difference, since the BD group showed relatively lower performance in the LCT and RCPM-B. Rather, it suggested that visual/attentional processing might induce a relatively higher level of oxygenation in the PFC of BD. The observed HbO2 concentration change pattern was largely in line with the TOI change discussed above, although it should be noted that the result of HbO2 concentration change could not be discussed as directly relating to the TOI value, since the HbO2 concentration value measured here changed from an arbitrary baseline, while TOI was expressed as an absolute value (percentage of HbO2 concentration to HbT concentration). It can be safely argued that the changes in both indices indicated a discrepancy in the function of the PFC between verbal versus non-verbal (figural/attentional) tasks in BD.

A previous NIRS study on healthy subjects reported that PFC hemodynamics showed two distinct patterns of HbO2 concentration and HbR concentration changes that reflected higher cognitive processing versus attention, respectively. Whereas the typical pattern for higher cognitive tasks is HbO2 concentration increase concomitant with HbR concentration decrease, attention tasks typically induced an increase of HbO2 concentration as well as a slight increase of HbR concentration (Fallgatter & Strik, 1997; Toichi et al. 2004). This pattern was also confirmed in the present study, suggesting that the utilization of oxygen in the PFC during attentional tasks seemed to be enhanced in healthy subjects as well as in BD patients.

As we hypothesized, in terms of PFC oxygenation, BD subjects showed an opposite tendency when contrasting higher verbal tasks with attentional/visual tasks. Compared with in healthy subjects, the BD group showed modest oxygenation in higher verbal tasks and prominent oxygenation in relatively simple visual/attentional tasks. Although the neurophysiological background of this tendency is not clear, one hypothesis is that possible subcortical pathophysiology might underlie the paradoxical PFC oxygenation pattern in BD. A previous study investigating hemodynamic changes in the PFC due to electrical stimulation of the deep brain reported an increase of both HbO2 concentration and HbR concentration during high-frequency stimulation of the thalamus (Sakatani et al. 1999). Similar overexcitement of the subcortical attention system in BD might induce the prominent HbO2 concentration increase concomitant with HbR concentration increase. Another hypothesis is that there might be abnormality of more widespread neural circuitries involving the PFC as well as other cortical regions in BD. For example, VFs are known to activate the PFC as well as temporal structures in healthy subjects (Mummery et al. 1996), and it is possible that our subjects with BD might recruit neural circuitries involving prefrontal and temporal lobes differently when compared with healthy subjects. This possibility needs to be further explored by using a multi-channel NIRS system covering the fronto-temporal cortical areas. Finally, there is a possibility that the possible oxygen metabolism pathophysiology in BD might be directly related to atypical PFC oxygenation. Recent studies suggested the tendency of anaerobic energy production or a shift from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis in the PFC of BD patients (Dager et al. 2004), which might partly explain the relatively modest PFC oxygenation during VF in BD.

The TOI level in the left DLPFC was higher than that in the right DLPFC in both groups, which was observed in the resting condition as well as task conditions. This tendency was more prominent in VF, suggesting that verbal processing induced left-dominant activation. Interestingly, additional analysis of TOI revealed that BD patients with moderate depressive symptoms showed a significantly higher TOI level in the left PFC under resting conditions as well as the LCT and RCPM-B. The result implied that depressive symptoms might be related to increased rCBF in the left PFC.

There are some limitations of this study. One is associated with the technique of NIRS, as the spatial resolution of NIRS is limited and the exact localization of the optodes on the brain surface was not conducted using MRI. Hemodynamic changes in other cortical areas need to be examined by a multi-channel NIRS approach; however, it should be noted that TOI measurement was made possible only by the present two-channel system and, to our knowledge, other multi-channel NIRS systems commercially available at present cannot assess the TOI level. Another limitation is the possible influence of medication on the results of this study. Recent studies reported decreased activation during verbal tasks in lithium-treated euthymic BD patients (Silverstone et al. 2005) or lithium- and sodium valproate-treated healthy subjects (Bell et al. 2005). Finally, a longitudinal study with a repeated-measures design in a different mood state is needed in order to determine whether the left-hemisphere activation revealed by TOI is a trait maker.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted as part of the Mood Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Case Medical Center (Ohio, USA). This work was supported by NIMH P20 MH-66054. Y.K. is supported by a research fellowship of the Uehara Memorial Foundation (Japan).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Adler CM, Holland SK, Schmithorst V, Tuchfarber MJ, Strakowski SM. Changes in neuronal activation in patients with bipolar disorder during performance of a working memory task. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:540–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawi PG, Kirkpatrick PJ. Tissue oxygen index: thresholds for cerebral ischemia using near-infrared spectroscopy. Stroke. 2006;37:2720–2725. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000244807.99073.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audenaert K, Brans B, Van Laere K, Lahorte P, Versijpt J, van Heeringen K, Dierckx R. Verbal fluency as a prefrontal activation probe: a validation study using 99mTc-ECD brain SPET. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2000;27:1800–1808. doi: 10.1007/s002590000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell EC, Willson MC, Wilman AH, Dave S, Silverstone PH. Differential effects of chronic lithium and valproate on brain activation in healthy volunteers. Human Psychopharmacology. 2005;20:415–424. doi: 10.1002/hup.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP, Leung HC, Skudlarski P, Lacadie CM, Fredericks CA, Harris BC, Charney DS, Gore JC, Krystal JH, Peterson BS. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of bipolar disorder: state- and trait-related dysfunction in ventral prefrontal cortices. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:601–609. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope M, Delpy DT. System for long-term measurement of cerebral blood and tissue oxygenation on new born infants by near infra-red transillumination. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing. 1988;26:289–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02447083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis VA, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Wright IC, Williams SC, Morris RG, Sharma TS, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Attenuated frontal activation during a verbal fluency task in patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1056–1063. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis VA, Dixon TA, Morris RG, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Sharma T, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Differential frontal activation in schizophrenia and bipolar illness during verbal fluency. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;66:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dager SR, Friedman SD, Parow A, Demopulos C, Stoll AL, Lyoo IK, Dunner DL, Renshaw PF. Brain metabolic alterations in medication-free patients with bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:450–458. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A, Meek JH, Clemence M, Elwell CE, Tyszczuk L, Cope M, Delpy DT. Optical pathlength measurements on adult head, calf and forearm and the head of the newborn infant using phase resolved optical spectroscopy. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 1995;40:295–304. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/40/2/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Kirkby BS, Van Horn JD, Ellmore TM, Berman KF. Context-dependent, neural system-specific neurophysiological concomitants of ageing: mapping PET correlates during cognitive activation. Brain. 1999;122:963–979. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.5.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallgatter A, Strik W. Right frontal activation during the continuous performance test assessed with near-infrared spectroscopy in healthy subjects. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;223:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13416-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallgatter AJ, Strik WK. Frontal brain activation during the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test assessed with two-channel near-infrared spectroscopy. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1998;248:245–249. doi: 10.1007/s004060050045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Maier J, Fabinai M, Mantulin W, Gratton E. Feasibility of intracranial near-infrared optical scanning. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann MJ, Ehlis AC, Fallgatter AJ. Bilaterally reduced frontal activation during a verbal fluency task in depressed patients as measured by near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004;16:170–175. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science. 1977;198:1264–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.929199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama M, Fukuda M, Yamagishi Y, Sato T, Uehara T, Ito M, Suto T, Mikuni M. Frontal lobe function in bipolar disorder: a multichannel near-infrared spectroscopy study. Neuroimage. 2006;29:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Kato N. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2000;2:180–190. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Takahashi S, Shioiri T, Inubushi T. Alterations in brain phosphorous metabolism in bipolar disorder detected by in vivo 31P and 7Li magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;27:53–59. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konradi C, Eaton M, MacDonald ML, Walsh J, Benes FM, Heckers S. Molecular evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:300–308. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakow K, Ries S, Daffertshofer M, Hennerici M. Simultaneous assessment of brain tissue oxygenation and cerebral perfusion during orthostatic stress. European Neurology. 2000;43:39–46. doi: 10.1159/000008127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Toichi M, Shimizu M, Mason RA, Coconcea CM, Findling RL, Yamamoto K, Calabrese JR. Prefrontal activation during verbal fluency tests in schizophrenia – a near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) study. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;77:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Toichi M, Shimizu M, Mason RA, Findling RL, Yamamoto K, Calabrese JR. Prefrontal hemodynamic activity predicts false memory – a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1783–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda S, Houkin K, Abe H, Hoshi Y, Tamura M. Near-infrared monitoring of cerebral oxygenation state during carotid endarterectomy. Surgical Neurology. 1996;45:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(95)00463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Folley BS, Gore J, Park S. Origins of spatial working memory deficits in schizophrenia: an event-related FMRI and near-infrared spectroscopy study. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Larson MP, DelBello MP, Zimmerman ME, Schwiers ML, Strakowski SM. Regional prefrontal gray and white matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matcher SJ, Elwell CE, Cooper CE, Cope M, Delpy DT. Absolute quantification methods in tissue near infrared spectroscopy. Proceedings of SPIE. 1995;2839:486–495. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Kato N, Kato T. Decreased cerebral haemodynamic response to cognitive and physiological tasks in mood disorders as shown by near-infrared spectroscopy. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1029–1037. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Watanabe A, Onodera Y, Kato N, Kato T. Prefrontal hemodynamic response to verbal-fluency task and hyperventilation in bipolar disorder measured by multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks PJ, Thompson JM, Bullmore ET, Suckling J, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Simmons A, Giles N, Lloyd AJ, Harrison CL, Seal M, Murray RM, Ferrier IN, Young AH, Curtis VA. A functional MRI study of working memory task in euthymic bipolar disorder: evidence for task-specific dysfunction. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:550–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummery CJ, Patterson K, Hodges JR, Wise RJ. Generating ‘tiger’ as an animal name or a word beginning with T: differences in brain activation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 1996;263:989–995. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlson GD, Barta PE, Powers RE, Menon RR, Richards SS, Aylward EH, Federman EB, Chase GA, Petty RG, Tien AY. Ziskind-Somerfeld Research Award 1996. Medial and superior temporal gyral volumes and cerebral asymmetry in schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, Halaris A, Selemon L. Reductions in neuronal and glial density characterize the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. Coloured Progressive Matrices: Sets A, AB, B. H. K. Lewis; London: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Sakatani K, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Suzuki S. Changes in cerebral blood oxygenation of the frontal lobe induced by direct electrical stimulation of thalamus and globus pallidus: a near infrared spectroscopy study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1999;67:769–773. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi RB, Stanley JA, Axelson D, Brambilla P, Nicoletti MA, Keshavan MS, Ramos RT, Ryan N, Birmaher B, Soares JC. Reduced NAA levels in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of young bipolar patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2109–2115. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20):22–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone PH, Bell EC, Willson MC, Dave S, Wilman AH. Lithium alters brain activation in bipolar disorder in a task- and state-dependent manner: an fMRI study. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2005;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Adler CM, Holland SK, Mills N, DelBello MP. A preliminary FMRI study of sustained attention in euthymic, unmedicated bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1734–1740. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wang JF, Tseng M, Young LT. Downregulation in components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in the postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2006;31:189–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toichi M, Findling RL, Kubota Y, Calabrese JR, Wiznitzer M, McNamara NK, Yamamoto K. Hemodynamic differences in the activation of the prefrontal cortex: attention vs. higher cognitive processing. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee P, Cope M, Arridge SR, Essenpreis M, Potter LA, Edwards AD, Wyatt JS, McCormick DC, Roth SC, Reynolds EOR, Delpy DT. Experimentally measured optical pathlengths for the adult head, calf and forearm and the head of the newborn infant as a function of inter optode spacing. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1992;316:143–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3404-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villringer A, Planck J, Hock C, Schleinkofer L, Dirnagl U. Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): a new tool to study hemodynamic changes during activation of brain function in human adults. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;154:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90181-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Zeigler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]