Abstract

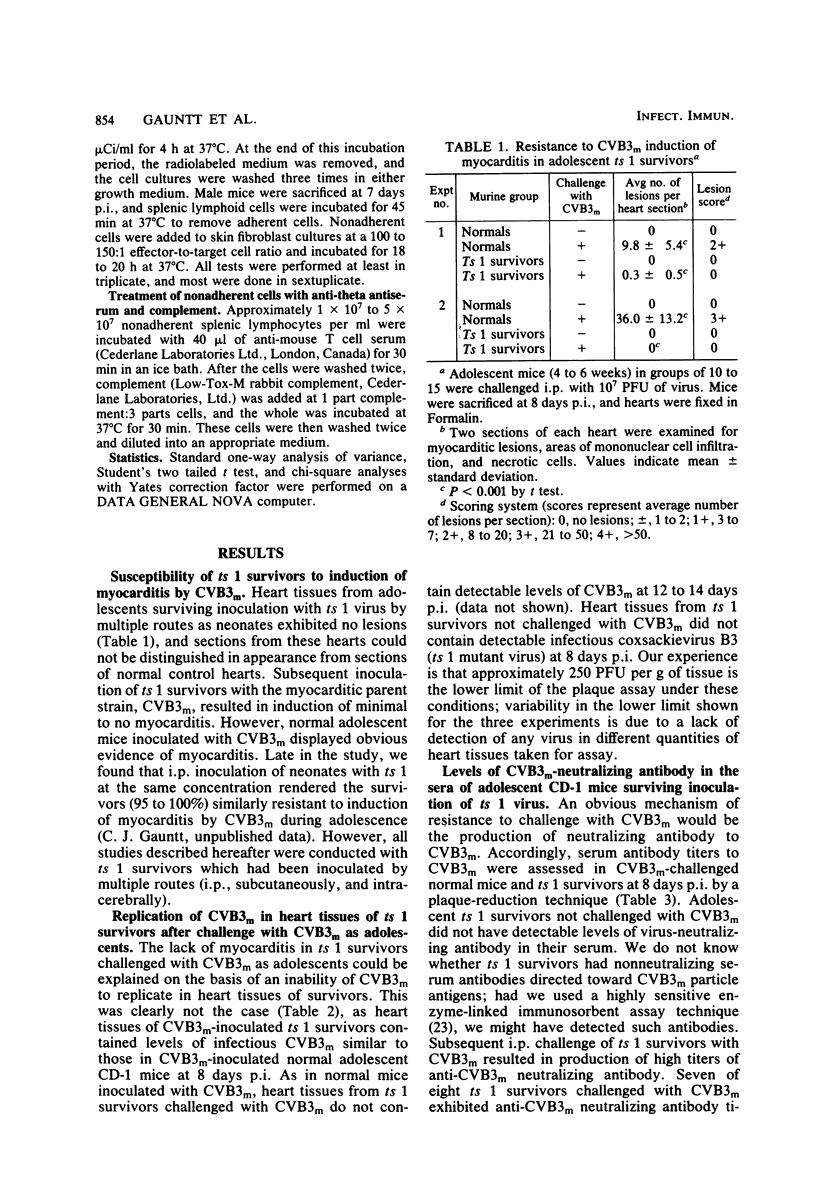

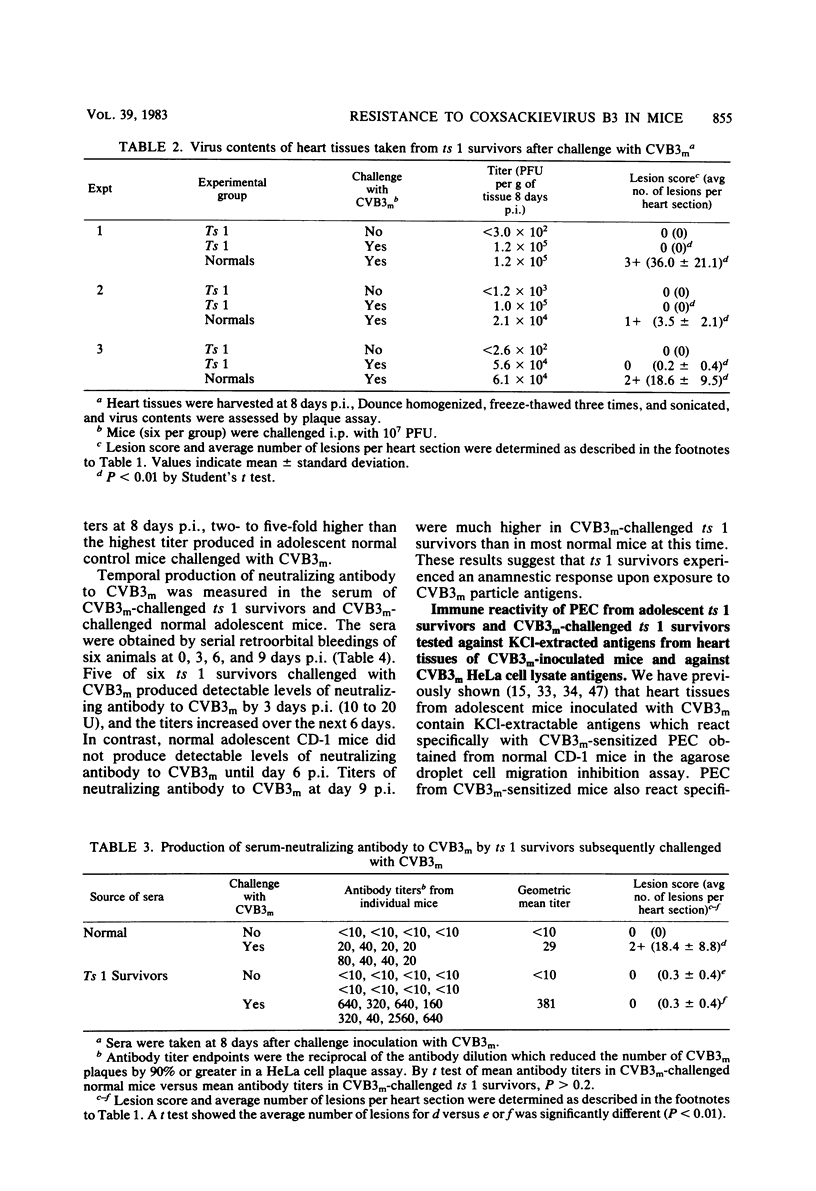

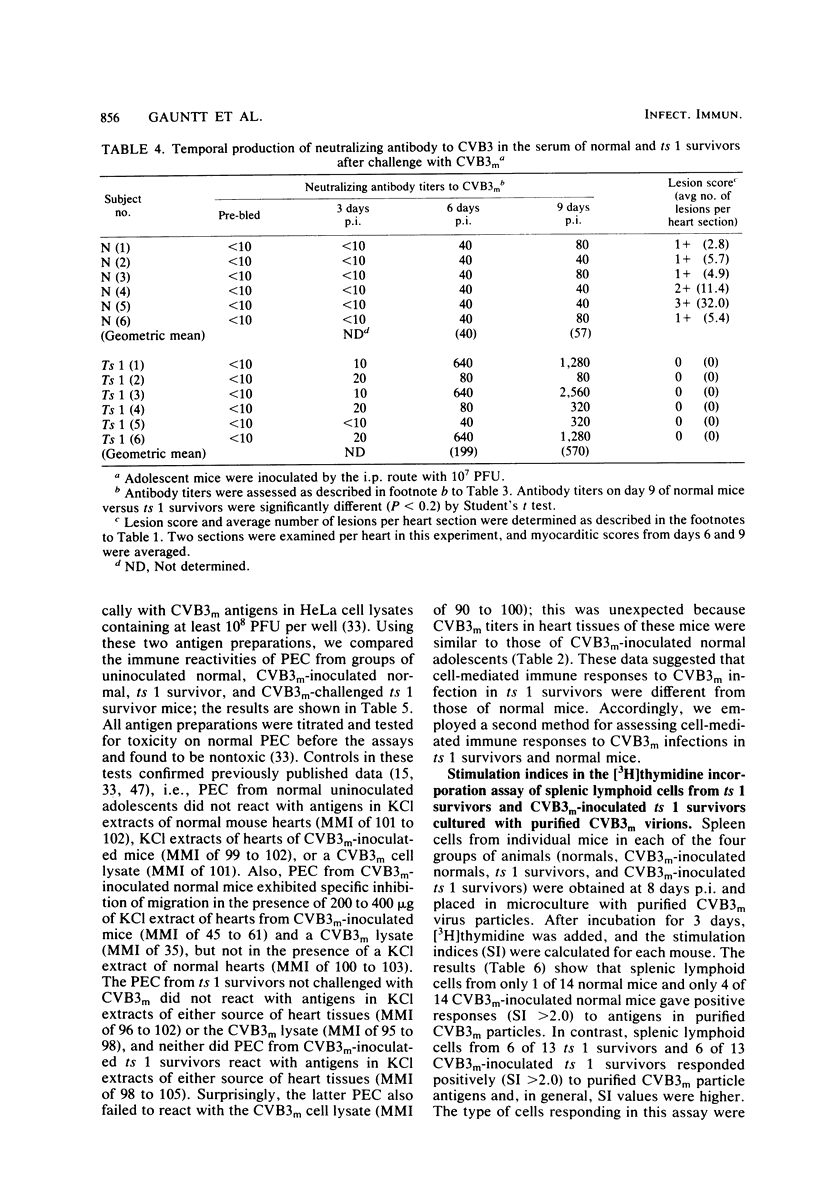

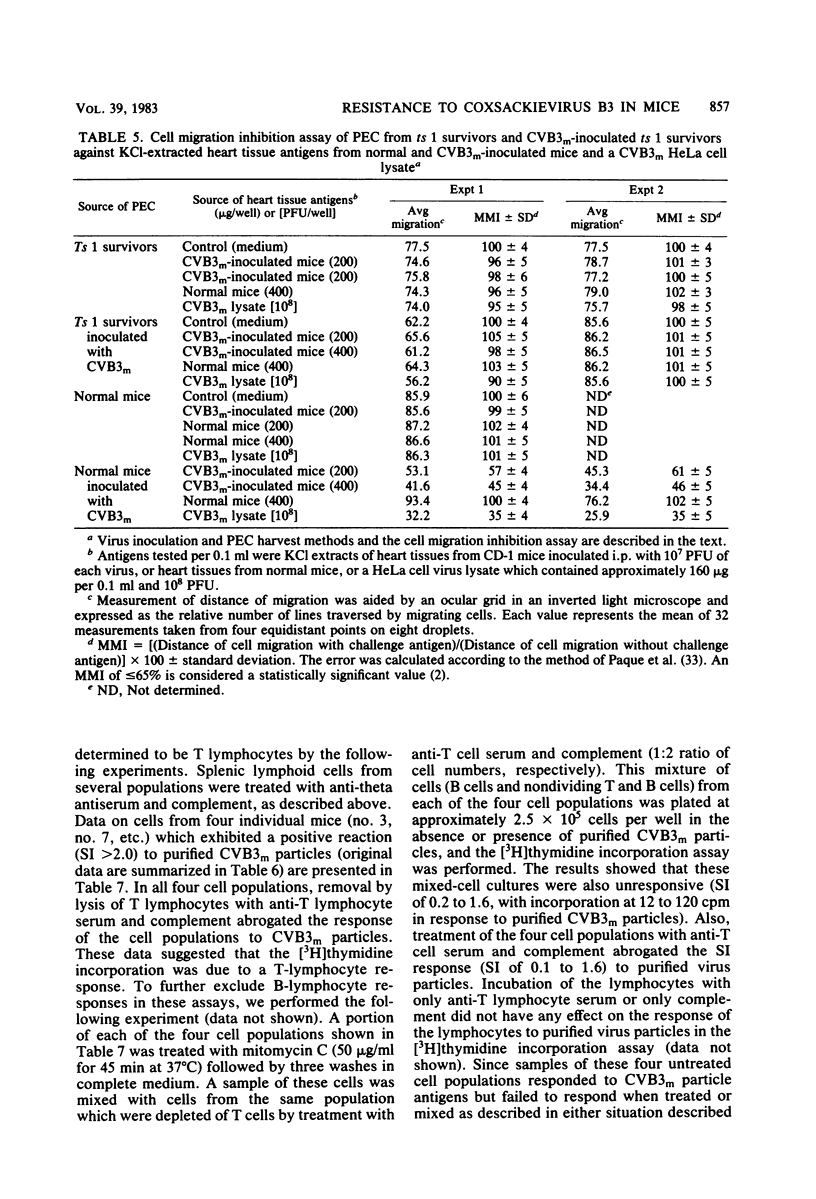

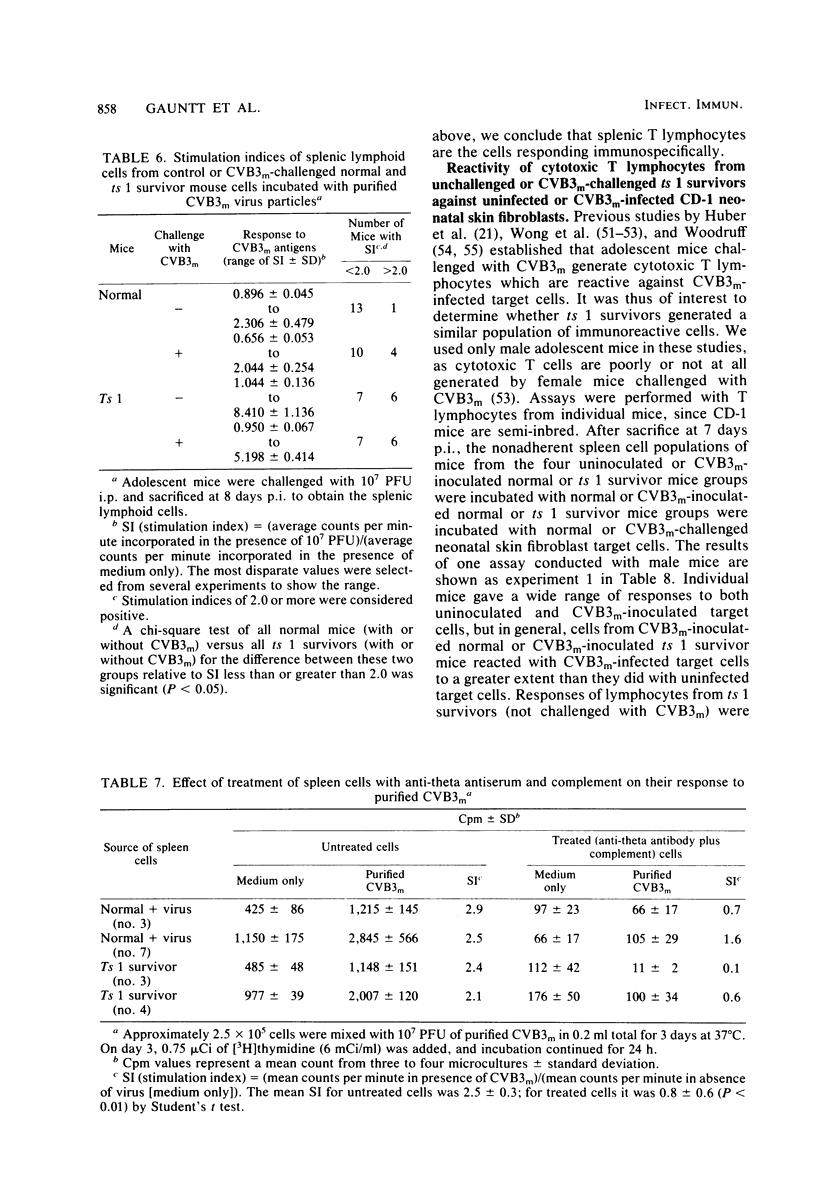

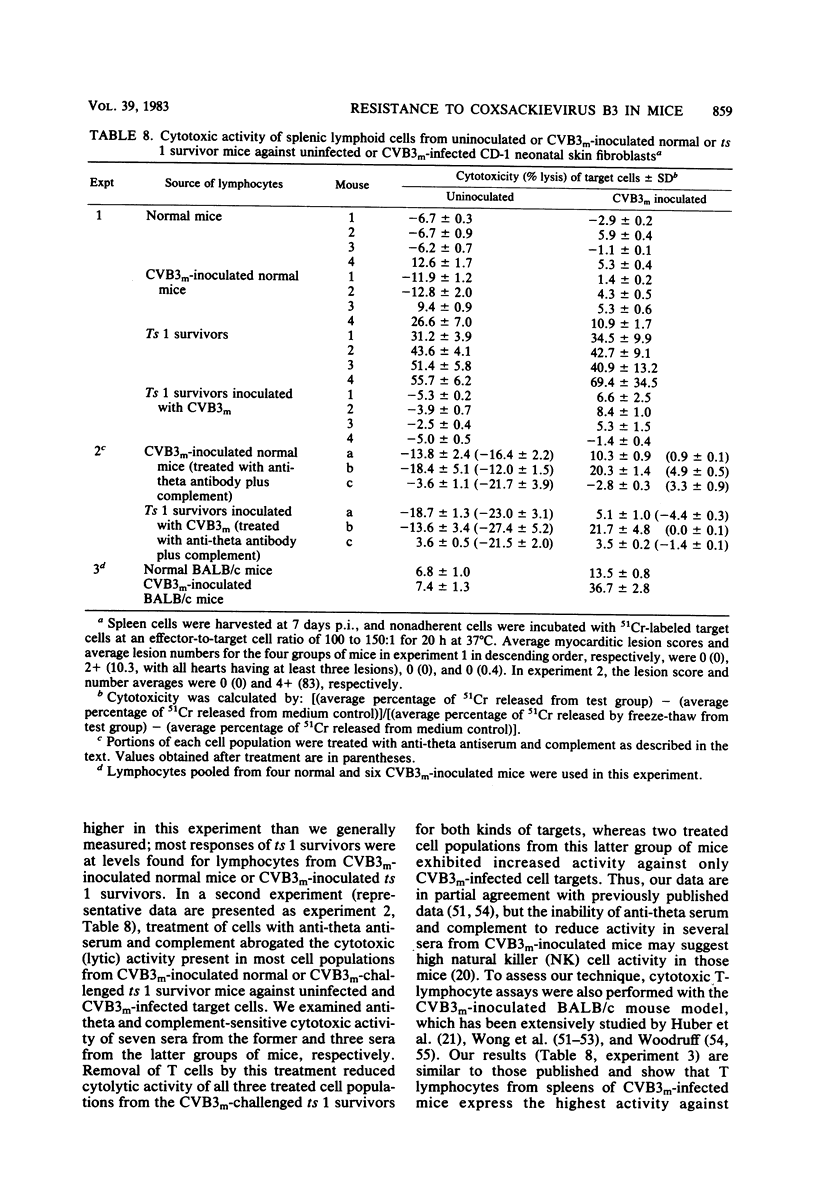

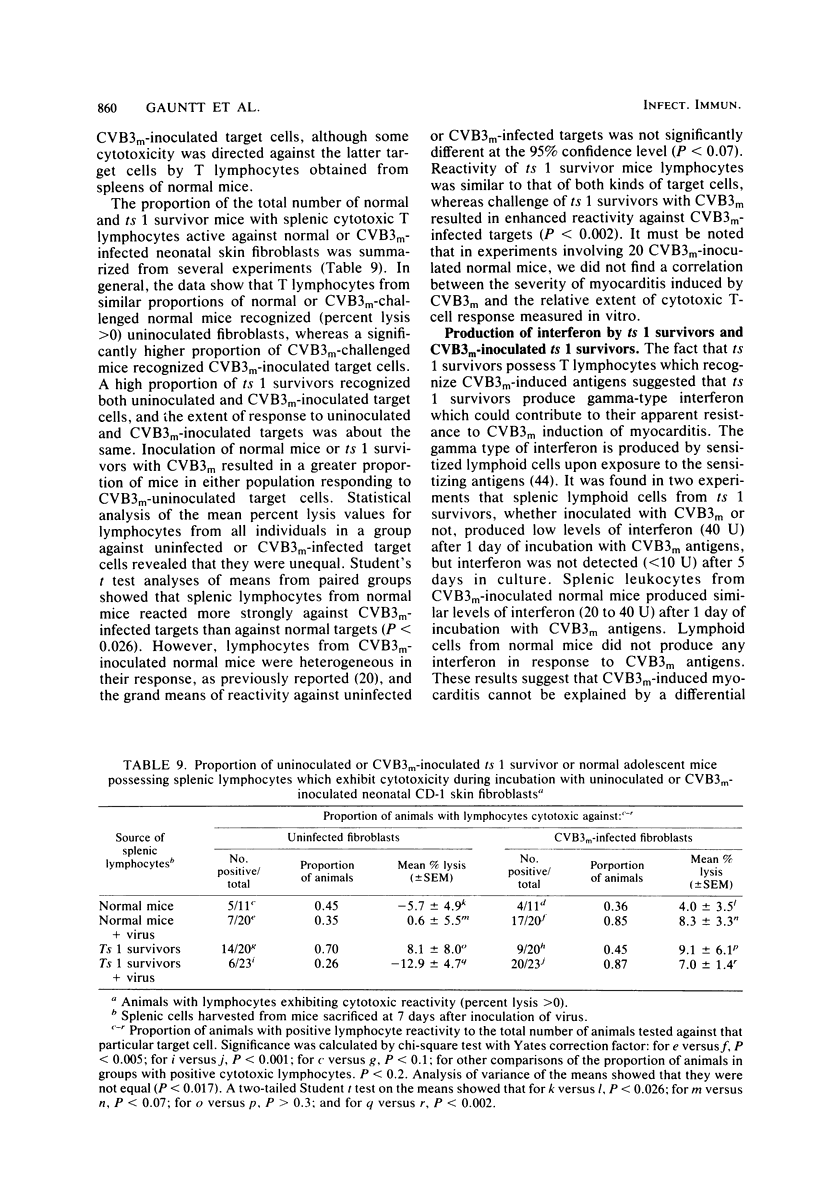

Inoculation of neonatal CD-1 mice by multiple routes with an amyocarditic temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant (ts 1) derived from a myocarditic parent variant of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3m) resulted in approximately half of the neonates surviving to adolescence. Challenge of the ts 1 survivors with CVB3m did not induce myocarditis, as assessed by histological examination of heart tissues. Virus was not detected in heart tissues of adolescent ts 1 survivors, but inoculation of these mice with CVB3m resulted in virus concentrations similar in titers to those found in CVB3m-inoculated normal adolescent mice. The ts 1 survivors did not contain detectable levels of anti-CVB3m neutralizing antibody, but upon challenge with CVB3m they produced antibody more rapidly and to higher titers than did normal CD-1 adolescents after primary inoculation with CVB3m. Cell-mediated immunity in ts 1 survivors was compared with that of normal mice after challenge with CVB3m. The capacity for production of migration inhibitory factor was assessed by the agarose droplet cell migration inhibition assay, using peritoneal exudate cells and a CVB3m cell lysate or KCl-extracted antigens from heart tissues of CVB3m-inoculated mice. Migration inhibitory factor activity was not detected in cultures of splenic leukocytes from ts 1 survivors of CVB3m-inoculated ts 1 survivors, but it was readily detected in cultures of splenic leukocytes from CVB3m-inoculated normal adolescent mice. The [3H]thymidine stimulation assay, performed with splenic lymphoid cells and purified CVB3m particles, revealed that lymphocytes from normal mice, whether inoculated with CVB3m or not, were not stimulated by CVB3m particle antigens, whereas lymphoid cells from a significantly higher proportion of ts 1 survivors, whether inoculated with CVB3m or not, responded with a stimulation index ≥2.0. The cells responding with positive stimulation were T lymphocytes. A higher proportion of normal mice and ts 1 survivors, both inoculated with CVB3m, contained splenic cytotoxic T lymphocytes with higher reactivity against CVB3m-infected neonatal skin fibroblasts than against normal skin fibroblasts, as assessed by a 51Cr release assay. The group of uninoculated ts 1 survivors present as a high proportion of individuals with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte reactivity against both uninoculated and CVB3m-inoculated skin fibroblasts. However, ts 1 survivors and normal mice possessed the same proportions of splenic lymphocytes carrying either allele for Lyt 1 and Lyt 2 surface markers. The results suggest two mechanisms by which ts 1 survivors exhibit resistance to CVB3m induction of myocarditis, namely, the rapid production of high-titered anti-CVB3m neutralizing antibody in response to CVB3m inoculation and altered cell-mediated immune responses against CVB3m-induced viral or novel cellular antigens. The data are compatible with the notion that an immune deviation mechanism, thought to be controlled through a mechanism requiring suppressor cell activity which inhibits macrophage activation in ts 1 survivors, protects these mice from induction of myocarditis.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Auerbach R. Studies on the development of immunity: the response to sheep red blood cells. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1972;7:257–280. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrand H., Källen B. On the statistical evaluation of the macrophage migration inhibition assay. Scand J Immunol. 1973;2(2):173–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1973.tb02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle W. An extension of the 51Cr-release assay for the estimation of mouse cytotoxins. Transplantation. 1968 Sep;6(6):761–764. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch G. E., Giles T. D. The role of viruses in the production of heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1972 Feb;29(2):231–240. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanana A. D., Joel D. D., Schaedeli J., Hess M. W., Cottier H. Thymus cell migration: 3HTdR-labeled and theta-positive cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues of newborn mice. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1973;29(0):79–85. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9017-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiscon M. Q., Golub E. S. Functional development of the interacting cells in the immune response. I. Development of T cell and B cell function. J Immunol. 1972 May;108(5):1379–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. D., Kearney J. F., Lydyard P. M., Grossi C. E., Lawton A. R. Studies of generation of B-cell diversity in mouse, man, and chicken. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1977;41(Pt 1):139–145. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1977.041.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE JAGER H., VAN CREVELD S. Myocarditis in newborns, caused by coxsackie virus; clinical and pathological data. Ann Paediatr. 1956 Jul-Aug;187(1-2):100–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djeu J. Y., Heinbaugh J. A., Holden H. T., Herberman R. B. Augmentation of mouse natural killer cell activity by interferon and interferon inducers. J Immunol. 1979 Jan;122(1):175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eardley D. D. Feedback suppression: an immunoregulatory circuit. Fed Proc. 1980 Nov;39(13):3114–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast L. D., Fan D. P. An adherent, radiosensitive accessory cell necessary for mouse cytolytic T lymphocyte response to viral antigen. J Immunol. 1981 Mar;126(3):1114–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelinger J. A., Neiderhuber J. E., David C. S., Shreffler D. C. Evidence for the expression of Ia (H-2-associated) antigens on thymus-derived lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1974 Nov 1;140(5):1273–1284. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.5.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauntt C. J. Synthesis of ribonucleic acids in KB cells infected with rhinovirus type 14. J Gen Virol. 1973 Nov;21(2):253–267. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-21-2-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauntt C. J., Trousdale M. D., LaBadie D. R., Paque R. E., Nealon T. Properties of coxsackievirus B3 variants which are amyocarditic or myocarditic for mice. J Med Virol. 1979;3(3):207–220. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington J. T., Jr, Stastny P. Macrophage migration from an agarose droplet: development of a micromethod for assay of delayed hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 1973 Mar;110(3):752–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto I., Komatsu T. Myocardial changes after infection with Coxsackie virus B3 in nude mice. Br J Exp Pathol. 1978 Feb;59(1):13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberman R. B., Ortaldo J. R. Natural killer cells: their roles in defenses against disease. Science. 1981 Oct 2;214(4516):24–30. doi: 10.1126/science.7025208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberman R. B., Ortaldo J. R., Timonen T. Assay of augmentation of natural killer cell activity and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by interferon. Methods Enzymol. 1981;79(Pt B):477–484. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)79061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S. A., Job L. P., Auld K. R., Woodruff J. F. Sex-related differences in the rapid production of cytotoxic spleen cells active against uninfected myofibers during Coxsackievirus B-3 infection. J Immunol. 1981 Apr;126(4):1336–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S. A., Job L. P., Woodruff J. F. Lysis of infected myofibers by coxsackievirus B-3-immune T lymphocytes. Am J Pathol. 1980 Mar;98(3):681–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janossy G., Greaves M. F. Lymphocyte activation. II. discriminating stimulation of lymphocyte subpopulations by phytomitogens and heterologous antilymphocyte sera. Clin Exp Immunol. 1972 Mar;10(3):525–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katze M. G., Crowell R. L. Immunological studies of the group B coxsackieviruses by the sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoprecipitation. J Gen Virol. 1980 Oct;50(2):357–367. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-2-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai C., Matsumori A., Kumagai N., Tokuda M. Experimental Coxsackie virus B-3 and B-4 myocarditis in mice. Jpn Circ J. 1978 Jan;42(1):43–47. doi: 10.1253/jcj.42.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown A. B. Viral Infections and diseases of the heart. Prog Med Virol. 1978;24:70–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A. M., Wilson F. M. Virus myocardiopathy. Prog Med Virol. 1973;15:63–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer M. S., Leonard E. J., Rapp H. J., Borsos T. Tumor-specific antigen solubilized by hypertonic potassium chloride. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1971 Sep;47(3):703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nossal G. J., Pike B. L. Differentiation of B lymphocytes from stem cell precursors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1973;29(0):11–18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9017-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notkins A. L. Immune mechanisms by which the spread of viral infections is stopped. Cell Immunol. 1974 Mar 30;11(1-3):478–483. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(74)90045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura K., Takemori T., Tokuhisa T., Tada T. Specific enrichment of the suppressor T cell bearing I-J determinants: parallel functional and serological characterizations. J Exp Med. 1977 Nov 1;146(5):1234–1245. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.5.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paque R. E., Gauntt C. J., Nealon T. J. Assessment of cell-mediated immunity against coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis in a primate model (Papio papio). Infect Immun. 1981 Jan;31(1):470–479. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.1.470-479.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paque R. E., Gauntt C. J., Nealon T. J., Trousdale M. D. Assessment of cell-mediated hypersensitivity against coxsackievirus B3 viral-induced myocarditis utilizing hypertonic salt extracts of cardiac tissue. J Immunol. 1978 May;120(5):1672–1678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paque R. E., Straus D. C., Nealon T. J., Gauntt C. J. Fractionation and immunologic assessment of KCl-extracted cardiac antigens in coxsackievirus B3 virus-induced myocarditis. J Immunol. 1979 Jul;123(1):358–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press J. L., Klinman N. R. Enumeration and analysis of antibody-forming cell precursors in the neonatal mouse. J Immunol. 1973 Sep;111(3):829–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rager-Zisman B., Allison A. C. Effects of immunosuppression on coxsackie B-3 virus infection in mice, and passive protection by circulating antibody. J Gen Virol. 1973 Jun;19(3):339–351. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-19-3-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rager-Zisman B., Allison A. C. The role of antibody and host cells in the resistance of mice against infection by coxsackie B-3 virus. J Gen Virol. 1973 Jun;19(3):329–338. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-19-3-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz E. L., Kung P. C., Goldstein G., Schlossman S. F. Separation of functional subsets of human T cells by a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Aug;76(8):4061–4065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisfeld R. A., Kahan B. D. Biological and chemical characterization of human histocompatibility antigens. Fed Proc. 1970 Nov-Dec;29(6):2034–2040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesing T. G., Landau B. J., Crowell R. L. Limited persistence of viral antigen in coxsackievirus B3 induced heart disease in mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1979 Mar;160(3):382–386. doi: 10.3181/00379727-160-40455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röllinghoff M., Starzinski-Powitz A., Pfizenmaier K., Wagner H. Cyclophosphamide-sensitive T lymphocytes suppress the in vivo generation of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1977 Feb 1;145(2):455–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.145.2.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissons J. G., Oldstone M. B. Killing of virus-infected cells by cytotoxic lymphocytes. J Infect Dis. 1980 Jul;142(1):114–119. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobo J. D., Paul W. E. Functional heterogeneity of murine lymphoid cells. II. Acquisition of mitogen responsiveness and of theta antigen during the ontogeny of thymocytes and "T" lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1972 Aug;4(4):367–380. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(72)90039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trousdale M. D., Paque R. E., Gauntt C. J. Isolation of Coxsackievirus B3 temperture-sensitive mutants and their assignment to complementation groups. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 May 23;76(2):368–375. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trousdale M. D., Paque R. E., Nealon T., Gauntt C. J. Assessment of coxsackievirus B3 ts mutants for induction of myocarditis in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1979 Feb;23(2):486–495. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.486-495.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson F. M., Miranda Q. R., Chason J. L., Lerner A. M. Residual pathologic changes following murine coxsackie A and B myocarditis. Am J Pathol. 1969 May;55(2):253–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. Y., Woodruff J. J., Woodruff J. F. Generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes during coxsackievirus B-3 infection. I. Model and viral specificity1. J Immunol. 1977 Apr;118(4):1159–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. Y., Woodruff J. J., Woodruff J. F. Generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes during coxsackievirus B-3 infection. III. Role of sex. J Immunol. 1977 Aug;119(2):591–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. Y., Woodruff J. J., Woodruff J. F. Generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes during coxsackievirus tb-3 infection. II. Characterization of effector cells and demonstration cytotoxicity against viral-infected myofibers1. J Immunol. 1977 Apr;118(4):1165–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff J. F. Lack of correlation between neutralizing antibody production and suppression of coxsackievirus B-3 replication in target organs: evidence for involvement of mononuclear inflammatory cells in host defense. J Immunol. 1979 Jul;123(1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff J. F. Viral myocarditis. A review. Am J Pathol. 1980 Nov;101(2):425–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff J. F., Woodruff J. J. Involvement of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of coxsackie virus B3 heart disease. J Immunol. 1974 Dec;113(6):1726–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinkernagel R. M., Rosenthal K. L. Experiments and speculation on antiviral specificity of T and B cells. Immunol Rev. 1981;58:131–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1981.tb00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Khatib M. R., Chason J. L., Ho K. L., Silberberg B., Lerner A. M. Coxsackievirus B4 myocarditis in mice: valvular changes in virus-infected and control animals. J Infect Dis. 1978 Apr;137(4):410–420. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]