Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) wiry mutants posed a mystery because their phenotype, wiry or shoestring leaves that lack leaf blade expansion, resembles virus-infected tomato plants (see figure). However, the wiry mutant phenotype is not transmissible from plant to plant, as an infection would be, but is caused by mutation (Lesley and Lesley, 1928). To examine this mystery, Yifhar et al. (pages 3575–3589) characterized a set of classical and newly isolated wiry mutants and found that they correspond to four complementation groups, with multiple alleles producing a broad phenotypic series. Identification of the responsible loci showed that all four WIRY loci, tomato orthologs of RNA Dependent RNA Polymerase6, ARGONAUTE7, DICER-LIKE4, and SUPPRESSOR of GENE SILENCING3, act in biogenesis of trans-acting short interfering RNAs (ta-siRNAs). ta-siRNAs are a class of small interfering RNAs that are transcribed from TAS loci and are processed into small RNAs that regulate multiple processes, including development and stress responses (reviewed in Rubio-Somoza et al., 2009).

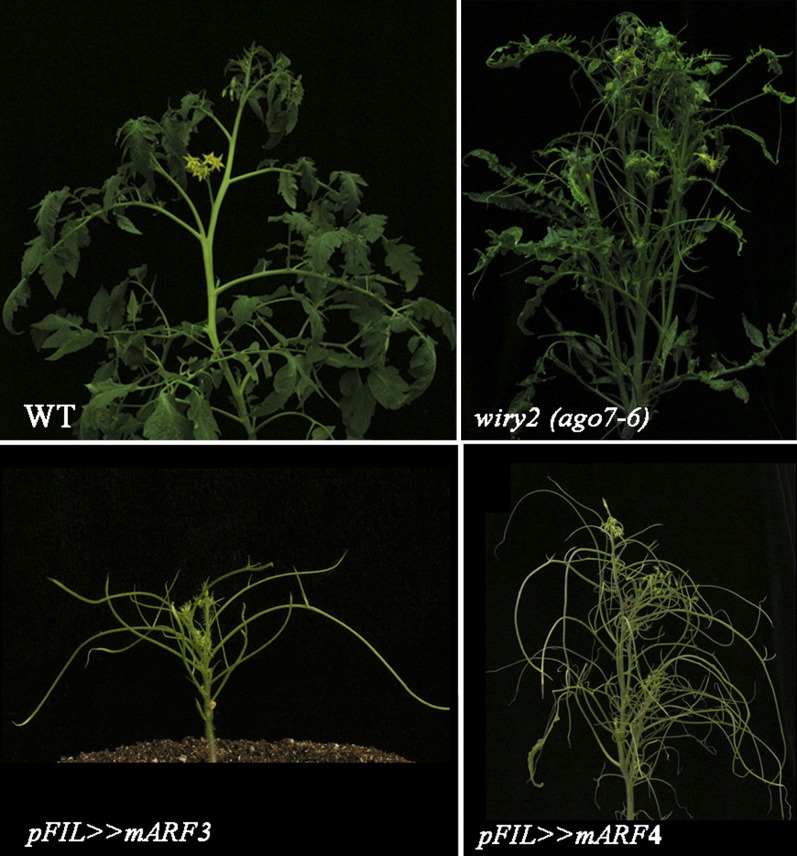

The tomato wiry phenotype can be recapitulated by ta-siRNA-insensitive ARFs. Top row, wild-type tomato plant (left) and wiry mutant (right); bottom row, transgenic plants expressing ARF3 insensitive to ta-siRNAs (left) and ARF4 insensitive to ta-siRNAs (right). (Figure courtesy of Tamar Yifhar and Yossi Capua.)

Why do mutations affecting ta-siRNAs cause a wiry phenotype? One of the key targets of ta-siRNA regulation is the auxin response, which is affected via regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS (ARFs). Indeed, the authors found misregulation of ta-siRNA targets ARF3 and ARF4 in the wiry mutants. Characterization of the small RNA profiles of the wiry mutants showed a strong effect on ta-siRNAs; specifically, the ta-siRNAs targeting ARF3 and ARF4 were strongly reduced in the wiry mutants, although different wiry mutants produced different effects. To prove that effects on ARFs produced the wiry phenotype, the authors expressed mutant forms of ARF3 and ARF4 that were insensitive to ta-siRNA regulation and found that, unlike the native forms, these recapitulated the wiry phenotype (see figure). Moreover, artificial microRNAs targeting ARFs could suppress the wiry1 phenotype, confirming that a failure to negatively regulate ARF3 and ARF4 was the basis for the wiry phenotype. However, the effect of wiry mutants may not be restricted to ARFs; for example, unlike the other wiry mutants, wiry3/dcl4 mutants formed necrotic lesions and this phenotype was not recapitulated by expression of the ta-siRNA-insensitive ARFs, indicating that DICER-LIKE4 may affect other targets.

What is the connection to virus infection? Short interfering RNAs act in the defense against invading nucleic acids, such as viruses; conversely, many viruses can suppress short interfering RNA production as part of infection (reviewed in Alvarado and Scholthof, 2009). For example, the Cucumber mosaic virus 2B protein can inhibit the slicing activity of an ARGONAUTE in Arabidopsis thaliana; also, reduced expression of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase increases susceptibility to Tobacco mosaic virus in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana). Indeed, Cucumber mosaic virus and Tomato mosaic virus also cause shoestring disease in tomatoes. Therefore, the viral suppressors and the wiry mutants likely affect the same ta-siRNA pathways, providing a solution to this mystery. However, this seemingly tidy solution may have a wrinkle, as expression of ta-siRNA-insensitive ARFs in Arabidopsis, potato, and tobacco did not produce a wiry phenotype. As symptoms of viral infection are also species specific, differential regulatory schemes are implied. The wiry mystery may thus have a few more chapters.

References

- Alvarado V., Scholthof H.B. (2009). Plant responses against invasive nucleic acids: RNA silencing and its suppression by plant viral pathogens. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20: 1032–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley J.W., Lesley M.M. (1928). The “wiry” tomato. A recessive mutant form resembling a plant affected with mosaic disease. J. Hered. 8: 337–344 [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Somoza I., Cuperus J.T., Weigel D., Carrington J.C. (2009). Regulation and functional specialization of small RNA-target nodes during plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12: 622–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yifhar T., Pekker I., Peled D., Friedlander G., Pistunov A., Sabban M., Wachsman G., Alvarez J.P., Amsellem Z., Eshed Y. (2012). Failure of the tomato trans-acting short interfering RNA program to regulate AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 and ARF4 underlies the wiry leaf syndrome. Plant Cell 24: 3575–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]