Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening reduces mortality yet remains underutilized. Low health literacy may contribute to this underutilization by interfering with patients’ ability to understand and receive preventive health services.

Purpose

To determine if a web-based multimedia CRC screening patient decision aid, developed for a mixed-literacy audience, could increase CRC screening.

Design

RCT. Patients aged 50–74 years and overdue for CRC screening were randomized to the web-based decision aid or a control program seen immediately before a scheduled primary care appointment.

Setting/Participants

A large community-based, university-affiliated internal medicine practice serving a socioeconomically disadvantaged population.

Main Outcome Measures

Patients completed surveys to determine their ability to state a screening test preference and their readiness to receive screening. Charts were abstracted by masked observers to determine if screening tests were ordered and completed.

Results

Between November 2007 and September 2008, a total of 264 patients enrolled in the study. Data collection was completed in 2009, and data analysis was completed in 2010. A majority of participants (mean age 57.8 years) were female (67%), African-American (74%), had annual household incomes of < $20,000 (76%), and had limited health literacy (56%). When compared to control participants, more decision-aid participants had a CRC screening preference (84% vs 55%, p<0.0001), and an increase in readiness to receive screening (52% vs 20%, p=0.0001). More decision-aid participants had CRC screening tests ordered (30% vs 21%) and completed (19% vs 14%), but no statistically significant differences were seen (AORs 1.6 [95% CI 0.97, 2.8] and 1.7 [95% CI 0.88, 3.2] respectively). Similar results were found across literacy levels.

Conclusions

The web-based decision aid increased patients’ ability to form a test preference and their intent to receive screening, regardless of literacy level. Further study should examine ways the decision aid can be combined with additional system changes to increase CRC screening.

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common noncutaneous cancer in the U.S., and the second-leading cause of cancer death.1 In order both to prevent CRC and reduce its associated mortality, several national organizations recommend routine CRC screening beginning at age 50 years.2;3 A variety of CRC screening tests are cost effective, giving patients and clinicians a choice of screening options.4

Despite the widespread recommendations for routine screening, CRC screening remains underutilized in the U.S. Approximately 40% of Americans aged 50–75 years remain unscreened.5 Barriers to CRC screening include patients’ unawareness of the threat of CRC or the benefits of screening, negative attitudes toward specific CRC screening tests, and lack of confidence in their personal ability to complete a complicated screening procedure.6–8 For the one third of Americans with limited health literacy skills, these barriers may be even greater.9–11

Decision aids can overcome these barriers by informing patients of screening options, correcting misperceptions, and encouraging patient–clinician communication.12 However, most patient oriented materials are written at advanced grade levels inaccessible to limited literacy patients. A study of over 170 published patient education materials found that only 5% were written at or below the 6th-grade level.13 In addition, a recent systematic review of web-based cancer decision aids found that none were written at less than the 8th-grade level, and only one third incorporated audio or video components.14

A well designed, multimedia decision aid may help overcome health literacy barriers by incorporating video, graphics, animations, and audio narratives using easy-to-understand language. Computer-assisted programs also can incorporate interactivity to engage the user and target the content delivered. Because even highly literate patients prefer easy-to-understand words and illustrations, a decision aid targeting low-literacy patients is likely to be well accepted by all.15 For these reasons, it was hypothesized that a web-based decision aid developed for a mixed-literacy audience would increase CRC screening in both low- and adequate-literacy patients. This hypothesis was tested in an RCT in a large medical practice.

Methods

The study was conducted at a community-based university-affiliated internal medicine faculty–resident practice serving a primarily socioeconomically disadvantaged patient population. The Wake Forest University IRB approved the study protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were patients aged 50–74 years who were scheduled for a routine (non-urgent care) medical visit and were overdue for CRC screening, defined as not having completed a home fecal occult blood test (FOBT) within the last year, a flexible sigmoidoscopy within the last 5 years, or a colonoscopy within the last 10 years. Potentially eligible patients were identified by querying the practice’s appointment schedule and electronic medical record for completion of CRC screening. A research assistant using a telephone script called scheduled patients to confirm eligibility and invite them to participate. A $10 gift card was offered for participation. Exclusion criteria included recent rectal bleeding, inability to speak English, or an obvious physical or mental impairment that would prevent a patient from interacting with the computer.

Participants arrived at the clinic 45 minutes before their scheduled appointment time. A research assistant verbally administered a baseline questionnaire that included demographic items, self-rated health status, questions about CRC screening and other preventive health items, and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).16 Using the REALM, each patient was classified as having limited health literacy (≤8th-grade reading level) or adequate health literacy (≥9th-grade reading level). Patients were then block randomized, stratified by literacy level, to view either a web-based CRC screening decision aid or a control program about prescription drug refills and safety. Both programs were displayed on a computer with a touch screen monitor and external speakers. Participants interacted with the programs in privacy.

The CRC screening decision aid, called CHOICE (Communicating Health Options through Interactive Computer Education, version 6.0W), was based on a previously validated videotape decision aid.17;18 The program is designed to be accessible to low-literacy patients by using easy-to-understand audio segments, video clips, graphics, and animations (Figure 1 and viewable at http://intmedweb.wfubmc.edu/choice/choice.html). CHOICE begins with a short introductory overview of CRC screening including CRC prevalence, the rationale for screening, and a description of common screening tests (FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy). The program then allows participants to choose to learn more about a specific test, view comparisons of the tests, or end the program. Prior to exiting, participants indicate their screening decision, and the program prints a corresponding one-page color handout. The program encourages all patients to discuss their screening decision with their healthcare provider. The control program about prescription drug refills and safety also incorporates multimedia and interactivity.

Figure 1.

Representative screen shot from CHOICE program. All written text is read aloud by a narrator. Patients interact with the program via a touch-screen monitor. The full decision aid may be viewed at http://intmedweb.wfubmc.edu/choice/choice.html.

Both programs were written in Flash CS4 Professional (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, California) and displayed in web browsers. Immediately following each program, participants completed a postprogram survey administered verbally by a research assistant and then proceeded to their scheduled medical appointments. Healthcare providers were not notified of patients’ enrollment in the study at any time, and study activities were conducted on a separate floor from the clinic. No attempts were made to influence the content of the medical visit, other than CHOICE encouraging patients to discuss CRC screening with their healthcare providers.

Outcomes Assessment

The primary outcome of interest was receipt of CRC screening within 24 weeks of study enrollment. This 24-week time frame was chosen a priori to allow participants time to reschedule their colonoscopy once and still have their screening captured. Secondary outcomes included patients’ ability to state a CRC test preference, patients’ change in readiness to receive CRC screening, and CRC test ordering at the visit immediately following the assigned program.

The study was designed to have 80% power to detect a 20% absolute difference in screening completion between CHOICE and control patients within individual literacy strata (limited literacy and adequate literacy). Assuming 15% of the control group would complete CRC screening, the target sample size was 146 patients in each literacy level. This recruitment goal was met for limited literacy patients, but due to slower than anticipated recruitment, enrollment ended with 117 adequate literacy patients, reducing the power to 70% in that stratum.

Receipt of CRC screening and test ordering were determined by chart review conducted by data collectors masked to study assignment. Two researchers independently reviewed a random sample of 10% of all charts, and there was 100% agreement. Patients’ ability to state a test preference was assessed on the postprogram survey by asking patients which CRC screening test they would want if all tests were free. Responses were coded categorically (“I don’t know enough about the tests to decide” versus choosing a specific testing option, including choosing never to be tested).

Readiness to receive screening was measured at baseline and immediately after the respective computer program with two identical questions: “Are you interested in being screened for colon cancer in the next 3 months?” and “Do you plan to ask your doctor about being screened for colon cancer at this visit?” Responses from these items were used to map each patient to a pre-action readiness stage according to the TransTheoretical Model’s Stages of Change: Precontemplation (not interested in being screened within the next 3 months), Contemplation (unsure if interested in screening but planning to discuss screening at this visit, or interested in being screened but not at this visit), and Preparation for Action (interested and plan to discuss screening immediately).19 Change in readiness to receive screening was determined by comparing patients’ readiness stage after the program to their baseline stage.

Data Analysis

Potential group differences in the baseline characteristics of the study participants were assessed using chi-square tests for proportions and t-tests for means. Chi-square tests were then used to assess unadjusted differences in the outcomes of interest. To guide the adjusted analyses, the association of each baseline characteristic with the outcome of interest was first analyzed bivariately. Logistic regression models were then created for each outcome, including as covariates any baseline characteristics that were distributed unevenly by arm (p<0.20) or associated with the outcome of interest in bivariate analyses (p<0.20). Potential covariates included patient sociodemographic factors (age, gender, race, income, employment status, marital status, health insurance status), patients’ self-rated health status, patients’ baseline readiness for screening, and the training level of the clinician. Because the mid-level clinicians all had greater than 10 years of practice experience, they were combined with the attending physicians for all analyses. Each model also included literacy level and tested for possible interactions between intervention and literacy. Similarly, each model tested for a possible interaction between intervention and baseline readiness stage given that the program may have different effects in patients with varying levels of readiness. Interaction terms were retained in the final models if the p-values were less than 0.05.

Two of the outcomes of interest were partially dependent on healthcare providers (test ordering and test completion). For these outcomes, generalized estimating equations were used to control for potential clinician clustering. Data collection was completed in 2009, and all analyses were completed in 2010 using SAS software version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Analyses were based on intention to treat. All tests for significance were two-sided with an alpha of 0.05.

Results

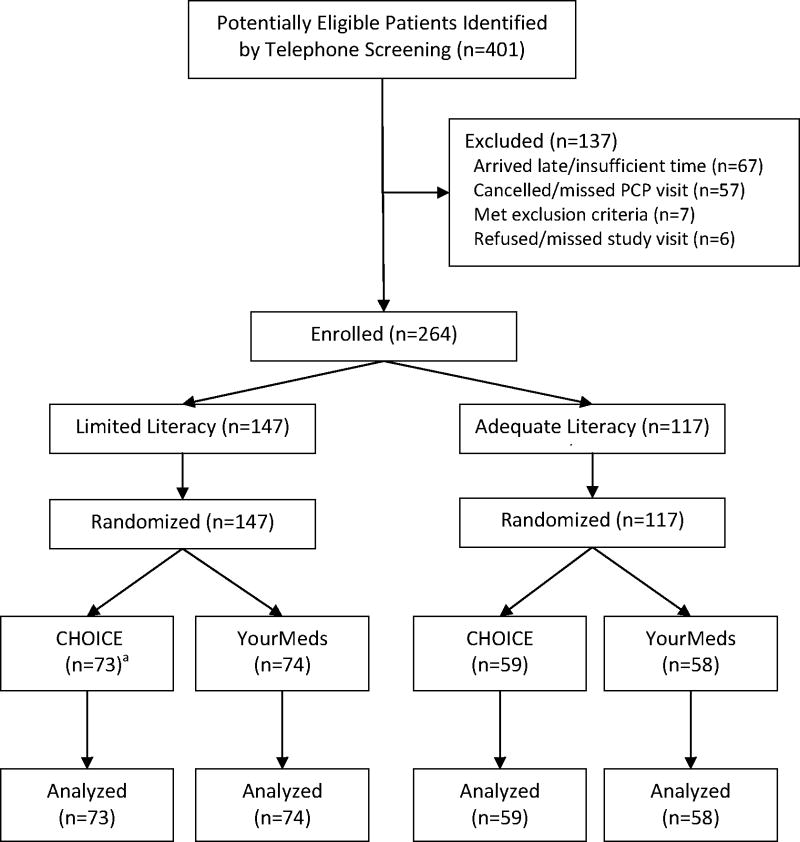

Between November 2007 and September 2008, research assistants reached 401 eligible patients by telephone who agreed to participate. Of these 401 patients, 264 arrived to the clinic 45 minutes early as directed, were confirmed eligible, and were enrolled. An equal number were randomized to the CRC decision aid (CHOICE) and the control program (Figure 2). While abstracting charts for the outcomes of interest, study staff discovered 16 randomized patients met exclusion criteria (15 were up to date on CRC screening and 1 reported recent rectal bleeding). All 16 patients denied these criteria on their eligibility questionnaires. Adhering to intention to treat principles, these 16 patients were included in all analyses. A sensitivity analysis excluding these patients did not change the results.

Figure 2.

Patient enrollment and randomization

a One patient allocated to CHOICE did not interact with the program due to a computer malfunction.

PCP, primary care provider

Table 1 displays patients’ baseline characteristics. The majority of the 264 participants were female, African-American, unemployed, and had annual household incomes of < $20,000. The mean age was 57.8 years. Approximately half rated their health status as poor or fair (52%), and had limited health literacy skills (56%). The only demographic factor not evenly distributed was lack of health insurance (32% of CHOICE patients vs 45% of control patients).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study sample at baseline, n(%) unless otherwise indicated

| CHOICE (n=132) | Control Program (n=132) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, M (SD) | 58.0 (6.7) | 57.6 (6.7) | 0.60 |

|

| |||

| Female | 87 (66) | 90 (68) | 0.69 |

|

| |||

| African-American | 100 (77) | 93 (71) | 0.28 |

|

| |||

| Annual household income ($) | 0.98 | ||

| <10,000 | 48 (39) | 48 (39) | |

| 10,000–19,999 | 45 (36) | 45 (37) | |

| ≥20,000 | 31 (25) | 29 (24) | |

|

| |||

| Married/Living Together | 31 (23) | 41 (31) | 0.17 |

|

| |||

| Employed | 37 (28) | 30 (23) | 0.30 |

|

| |||

| Uninsureda | 42 (32) | 59 (45) | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Education | 0.50 | ||

| Less than high school | 46 (35) | 44 (33) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 46 (35) | 40 (30) | |

| Some college or greater | 39 (30) | 48 (36) | |

|

| |||

| Health Literacy | 0.90 | ||

| Limited (< 9th grade) | 73 (55) | 74 (56) | |

| Adequate (≥9th grade) | 59 (45) | 58 (44) | |

|

| |||

| Self-reported Health Status | 0.54 | ||

| Poor | 16 (12) | 22 (17) | |

| Fair | 48 (36) | 52 (40) | |

| Good | 48 (36) | 39 (30) | |

| Very Good/Excellent | 20 (15) | 18 (14) | |

|

| |||

| Readiness for CRC screening | 0.39 | ||

| Precontemplation | 47 (36) | 39 (30) | |

| Contemplation | 26 (20) | 23 (17) | |

| Preparation for Action | 59 (45) | 70 (53) | |

|

| |||

| Training Level of Clinician | 1.00 | ||

| Resident physician | 55 (42) | 55 (42) | |

| Attending or mid-level (PA, NP) | 77 (58) | 77 (58) | |

Includes nine patients with no commercial or governmental health insurance who were enrolled in a charity care program

CRC, colorectal cancer; GED, NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician’s assistant

Of the 132 patients randomized to the CHOICE program, 131 patients (99%) viewed the 6.3-minute introductory overview, and 55 patients (42%) chose to watch at least one other segment of the program. One patient did not see the program due to a computer malfunction. Overall, the median time viewing CHOICE was 10.1 minutes (interquartile range 7.7 – 13.4 minutes). Average viewing time did not differ by literacy level (p=0.91).

Overall Results

Table 2 summarizes the main outcomes of interest. More CHOICE patients than control patients reported a preference for a specific CRC screening option after interacting with the assigned program (84% vs 55%, p<0.0001). After controlling for marital status, insurance status, literacy level, baseline readiness stage, and provider training, the odds of having a test preference were approximately 5 times greater for CHOICE patients compared to control program patients (OR 5.3, 95% CI 2.8, 10.1). Overall, the most preferred tests were FOBT (37.9%) and colonoscopy (33.5%).

Table 2.

Patient outcomes, CHOICE versus control program, n(%) unless otherwise indicated

| Patient Outcome | CHOICE (n=132) | Control (n=132) | Unadjusted OR | AOR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Reported a test preference after program | 110 (84) | 72 (55) | 4.3 (2.4, 7.7) | <0.0001 | 5.3 (2.8, 10.1)a | <0.0001 |

| Increased readiness for screening after programb | 38 (52) | 12 (20) | 4.4 (2.0, 9.7) | <0.001 | 4.7 (1.9, 11.9)c | 0.001 |

| Had screening test ordered at first visit | 40 (30) | 28 (21) | 1.6 (0.92, 2.8) | 0.09 | 1.6 (0.97, 2.8)a | 0.07 |

| Completed screening test within 24 weeks | 25 (19) | 18 (14) | 1.5 (0.76, 2.9) | 0.25 | 1.7 (0.88, 3.2)a | 0.12 |

Adjusted for marital status (married/living together vs other), health insurance (yes/no), literacy level, baseline readiness stage, and provider training level (resident physician vs attending/mid-level provider).

Analysis limited to participants in the precontemplation or contemplation stages at baseline (73 in CHOICE, 61 in Control)

Adjusted for marital status (married/living together vs other); health insurance (yes/no); literacy level; race (black vs other); annual household income (<$20,000 vs ≥$20,000); and employment status (employed vs other)

Approximately half of patients (129/264) entered the study at the Preparation for Action stage, and therefore could not increase their readiness for screening further. For patients at the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages, 52% (38/73) of CHOICE patients moved to a more favorable stage on the postprogram surveys compared to 20% (12/61) of control patients (p=0.0001). Few patients moved to a less favorable stage (6 CHOICE patients and 1 control patient). The increased readiness for screening associated with CHOICE remained significant after controlling for demographic factors (OR 4.7, 95% CI 1.9, 11.9).

More decision-aid patients had CRC screening tests ordered immediately after they viewed the program, but the difference was not significant (30% vs 21%, p=0.09). Adjusting for demographics and provider training yielded similar results (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.97, 2.8, p=0.07). Similarly, there was a nonsignificant difference between groups in the proportion of patients who completed a screening test within 24 weeks (19% for CHOICE vs 14% for control, p=0.25). The difference in screening test completion remained nonsignificant after adjustment for patient and provider factors (OR 1.7, 95% CI 0.88, 3.2, p=0.12).

In all analyses, there was no significant interaction between CHOICE and literacy level, or between CHOICE and patients’ baseline readiness for screening.

Effect of Literacy Level

The intervention showed similar effects in limited literacy and adequate literacy patients (Table 3). The CHOICE group was more likely than the control group to report a test preference and to increase screening readiness compared to baseline, regardless of literacy level. For both limited literacy and adequate literacy patients, the absolute differences in test ordering and test completion associated with CHOICE were similar but not significant in unadjusted or adjusted analyses.

Table 3.

Patient outcomes stratified by literacy level, n(%) unless otherwise indicated

| Patient Outcome | Limited Literacy | Adequate Literacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHOICE (n=73) | Control (n=74 ) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | CHOICE (n=59) | Control (n=58) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Reported a test preference after program | 55 (76) | 38 (51) | 3.1 (1.5, 6.2)** | 3.9 a (1.7, 8.7)* | 55 (93) | 34 (60) | 9.3 (3.0, 29.2)* | 9.8a (3.0, 32.3) * |

| Increased readiness for screening after programb | 24 (60) | 8 (24) | 4.9 (1.8, 13.4)** | 4.9c (1.4, 16.4) ** | 14 (42) | 4 (15) | 4.2 (1.2, 15.0)*** | 5.7c (1.1, 30.2) *** |

| Had screening test ordered at first visit | 25 (34) | 19 (26) | 1.5 (0.74, 3.1) | 1.6 a (0.83, 3.2) | 15 (25) | 9 (16) | 1.9 (0.74, 4.7) | 2.4 a (0.99, 5.9) |

| Completed screening test within 24 weeks | 15 (21) | 12 (16) | 1.3 (0.58, 3.1) | 1.7 a (0.69, 4.4) | 10 (17) | 6 (10) | 1.8 (0.60, 5.2) | 1.9 a (0.70, 5.0) |

Adjusted for marital status (married/living together vs other), health insurance (yes/no), baseline readiness stage, and provider training level (resident physician vs attending/mid-level provider)

Analysis limited to participants in the precontemplation or contemplation stages at baseline

Adjusted for marital status (married/living together vs other); health insurance (yes/no); race (black vs other); annual household income (<$20,000 vs ≥$20,000); and employment status (employed vs other)

p<0.001

p≤0.01

p<0.05

Influence of Readiness to Receive Screening

Regardless of treatment arm, patients’ final derived stage (Precontemplation, Contemplation, or Preparation for Action) predicted test ordering and completion. Patients in the Preparation for Action stage were three times more likely to have a screening test ordered and completed when compared to patients in the Precontemplative stage (34.0% vs 8.2% for test ordering, p=0.0001; 22.2% vs 6.6% for test completion, p<0.01). Of note, only one third of patients who indicated they wanted immediate screening had a screening test ordered.

Discussion

The web-based decision aid (CHOICE) increased patients’ ability to state a test preference and their readiness to receive screening, regardless of literacy level. In addition, more CHOICE patients had CRC screening tests immediately ordered and completed, but these differences were modest and did not reach significance.

Prior studies have examined the use of video or web-based interventions to increase CRC screening. Patient education videos without a decision-aid component have shown mixed results. Two trials found no significant increase in CRC screening,20;21 whereas a third study in a Latino immigrant population and coupled with a provider reminder found increased screening.22 None of these trials assessed patient literacy, and over 50% of patients in the two former trials had at least some years of education beyond high school.

The CRC decision aids have shown more promise. One trial of a videotape-based decision aid and a second trial of a web-based decision aid found increased screening rates.17;23 However, approximately 80% of patients in the videotape decision-aid trial were high school graduates, and the web-based decision aid required reading skills and prior computer experience.

A recent trial tested a CRC decision aid in a population with low educational attainment.24 Literacy levels were not formally measured, and the paper-based decision aid with accompanying DVD was limited to fecal occult blood screening. Informed decision making and knowledge were higher in the decision-aid group, but attitudes toward screening and completion of screening were lower.

This current study represents the first time patient literacy has been measured in a CRC decision- aid trial, allowing the effect of the decision aid to be examined in users with varying literacy levels. This current study adds the important finding that a decision aid developed for a mixed- literacy audience can effectively inform and motivate both low- and adequate-literacy patients. Knowing that patients with varying literacy levels will be amenable to a single easy-to- understand decision aid obviates the need to develop different interventions for different literacy groups. Rather, creating an intervention appropriate for lower-literacy patients should be well accepted across educational levels.

Several mechanisms could explain how CHOICE increased patients’ readiness to be screened. On the simplest level, CHOICE serves as a “just in time” patient reminder, a strategy known to increase screening rates.25;26 CHOICE also addresses lack of awareness of the need for CRC screening, the most common barrier reported by patients.27 In addition, by including reassuring interviews with patients who successfully completed screening, CHOICE may decrease test anxiety and increase patients’ confidence in their ability to complete the screening procedure. Lastly, a direct physician recommendation is one of the most potent predictors of CRC screening, and CHOICE includes a video clip of a physician recommending screening.28

Despite patients’ increased readiness to be screened, only one third of patients who wanted immediate screening had a screening test ordered. This discrepancy suggests the presence of additional system barriers, such as lack of time and competing priorities. Physicians often report insufficient time to address preventive services.29;30 If patients in this study presented with acute problems requiring attention, less time would have been available to address screening needs.

Communication difficulties may also contribute to the gap between patient intent and screening. Low-literacy patients are particularly vulnerable to communication difficulties and are less likely to ask questions in a medical visit.31;32 Although CHOICE encourages patients to discuss their screening decisions with their doctors, further patient coaching may be needed.

Increasing CRC screening will likely require a combination of system changes. One advocated practice structure is the “patient-centered medical home” which states that medical care should be coordinated, leverage information technology, and encourage active patient participation.33

Combining CHOICE with standing orders that allow nurses to order CRC screening tests could lessen the time demands on medical providers and potentially increase screening rates. Telephone follow-up protocols for nursing staff to contact patients several days after viewing CHOICE could provide another opportunity for patient coaching and screening outside the medical visit.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. Despite the randomized design, insurance status was not evenly distributed. For this reason, insurance status was included in all multivariable models although it did not change the results. Second, research assistants who administered post–decision aid questionnaires were not blinded; however, the clinical outcome assessors were. Third, the study was not designed to detect small to modest-sized effects (5%–10% increase in screening effects of the decision aid). Further study is warranted to determine if the observed improvements in screening are robust.

The study was designed to examine the effects of a single administration of decision support on immediate changes in screening readiness and test ordering, as well as test completion over 24 weeks. Reinforcement of the initial message of CHOICE (through reminders or additional information) may produce stronger effects. In addition, the chart reviews may have missed screening performed outside the institution, but anecdotal experience indicates that the practice’s low-income patients rarely receive screening services elsewhere. Although healthcare providers were not notified of their patients’ participation, the participants may have informed their healthcare providers of their enrollment which could affect provider behavior.

Additional factors that may have affected screening utilization, such as transportation difficulties and comorbidities, were not measured. Similarly, the study did not measure whether patients discussed CRC screening with their healthcare providers or why patients failed to complete screening. Lastly, as with any single site study, the findings may not apply to other patient populations.

Conclusion

The web-based CRC screening decision aid (CHOICE) increased test preferences and patients’ readiness to receive screening, irrespective of literacy level. The decision aid’s ability to effectively convey information with little staff involvement may make it a valuable resource for time-strapped clinics. Future research should focus on ways decision aids such as CHOICE can be combined with other system-level interventions to increase CRC screening.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer M. Griffith, DrPH, MPH, assisted with the decision-aid development. Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH, provided input on multivariate model construction.

This study was funded by a Cancer Control Career Development Award (DPM) from the American Cancer Society (CCCDA-05-162-01).

MPP was supported by a National Cancer Institute Established Investigator Award (K05 CA129166). No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical Trial #: NCT00558233

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130–160. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignone M, Saha S, Hoerger T, Mandelblatt J. Cost-effectiveness analyses of colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(2):96–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening among adults aged 50–75 years—U.S 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(26):808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkowitz Z, Hawkins NA, Peipins LA, White MC, Nadel MR. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening behaviors among average-risk older adults in the U. S Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(4):339–359. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(19):1406–1422. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.19.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolan NC, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, Fitzgibbon ML, Rademaker A, Liu D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: does literacy make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2617–2622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller DP, Jr, Brownlee CD, McCoy TP, Pignone MP. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of colorectal cancer screening: a survey study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col NF, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace LS, Lennon ES. American Academy of Family Physicians patient education materials: can patients read them? Fam Med. 2004;36(8):571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Readability and cultural sensitivity of web-based patient decision aids for cancer screening and treatment: a systematic review. Med Inform Internet Med. 2007;32(4):263–286. doi: 10.1080/14639230701780408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA. 1999;281(6):552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(10):761–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Whitney A, Hayter S, Lewis C, Campbell M, Sutherland L, et al. Development and initial testing of a computer-based patient decision aid to promote colorectal cancer screening for primary care practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell MK, James A, Hudson MA, Carr C, Jackson E, Oakes V, et al. Improving multiple behaviors for colorectal cancer prevention among african american church members. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):492–502. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zapka JG, Lemon SC, Puleo E, Estabrook B, Luckmann R, Erban S. Patient education for colon cancer screening: a randomized trial of a video mailed before a physical examination. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(9):683–692. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-9-200411020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aragones A, Schwartz MD, Shah NR, Gany FM. A randomized controlled trial of a multilevel intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among Latino immigrants in a primary care facility. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):564–567. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruffin MT, Fetters MD, Jimbo M. Preference-based electronic decision aid to promote colorectal cancer screening: results of a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The Health Belief Model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education. San Francisco: John Wiley; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holden DJ, Jonas DE, Porterfield DS, Reuland D, Harris R. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(10):668–676. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Thompson T, Shapiro JA, Vernon SW, et al. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2093–2103. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarfaty M, Wender R. How to increase colorectal cancer screening rates in practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(6):354–366. doi: 10.3322/CA.57.6.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayres CG, Griffith HM. Perceived barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of priority clinical preventive services guidelines. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(3):150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz MG, Jacobson TA, Veledar E, Kripalani S. Patient literacy and question-asking behavior during the medical encounter: a mixed-methods analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):782–786. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0184-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient Centered Medical Home. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2007. www.medicalhomeinfo.org/downloads/pdfs/jointstatement.pdf. [Google Scholar]