Abstract

Background

Endogenous estrogens play an important role in the overall cardiocirculatory system. However, there are no studies exploring the hormone metabolism and signaling pathway genes together on ischemic stroke, including sulfotransferase family 1E (SULT1E1), catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT), and estrogen receptor α (ESR1).

Methods

A case-control study was conducted on 305 young ischemic stroke subjects aged ≦ 50 years and 309 age-matched healthy controls. SULT1E1 -64G/A, COMT Val158Met, ESR1 c.454−397 T/C and c.454−351 A/G genes were genotyped and compared between cases and controls to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with ischemic stroke susceptibility. Gene-gene interaction effects were analyzed using entropy-based multifactor dimensionality reduction (MDR), classification and regression tree (CART), and traditional multiple regression models.

Results

COMT Val158Met polymorphism showed a significant association with susceptibility of young ischemic stroke among females. There was a two-way interaction between SULT1E1 -64G/A and COMT Val158Met in both MDR and CART analysis. The logistic regression model also showed there was a significant interaction effect between SULT1E1 -64G/A and COMT Val158Met on ischemic stroke of the young (P for interaction = 0.0171). We further found that lower estradiol level could increase the risk of young ischemic stroke for those who carry either SULT1E1 or COMT risk genotypes, showing a significant interaction effect (P for interaction = 0.0174).

Conclusions

Our findings support that a significant epistasis effect exists among estrogen metabolic and signaling pathway genes and gene-environment interactions on young ischemic stroke subjects.

Introduction

Previous population-based epidemiological studies reported stroke incidence rate to be lower in women during midlife than that in either older aged women or men [1], [2]. The relatively high risk of ischemic stroke in premature menopause or early menopause women has drawn attention to the role of estrogen in cardiovascular disease. In addition to experimental studies demonstrating the protective roles of estrogens in many forms of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [3]–[5], a large volume of epidemiological and observational findings also indicate that exposure to endogenous estrogen has been postulated to be protective for stroke in premenopausal women [6], [7]. It is well established that the beneficial effects of estrogen on vascular system includes enhancing nitric oxide (NO) production and vascular relaxation [8], [9], accelerating endothelial growth factor after vascular injury [4], [10], improving serum lipid concentration [11]–[13]. Since abundant evidence demonstrates that estrogen might play an important role in the overall cardiocirculatory system, understanding the estrogen metabolic and signaling pathway in relation to vascular disease may shed light on the role of estrogen in ischemic stroke pathogenesis. In this study, we focused on 3 genes involved in steroid hormone metabolism and signaling: sulfotransferase family 1E (SULT1E1), catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT), and estrogen receptor α (ESR1).

Sulfotransferase enzyme encoded by SULT1E1 (OMIM600043) catalyzes the sulfate conjugation of estrone (E1), 17β-estradiol (E2), catecholestrogens and 2-methoxyestradiol [14]–[16], which is a major pathway for estrogen metabolism in humans [15], [17]. The human SULT1E1 gene is approximately 20 kb in length, consists of eight exons, and maps to chromosome 4q13 [18]. There are 23 polymorphisms identified in the SULT1E1 gene, and most of them are in low allele frequencies except -64G/A in exon1 and other three in intron [19]. Recent researches further indicated that SULT1E1 -64G/A (rs3736599) in the promoter region is positively correlated with endometrial cancer risk [20], [21]. COMT, encoding catechol-O-methyltransferase, is a phase II enzyme that catalyzes the inactivation of the major metabolites of estrogen [22]. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) for COMT gene (OMIM16790), mapping to chromosome 22q11 in exon 4 (Val158Met, rs4680), has been identified the Met (A) allele is linked to a variant of the COMT gene, which results in 3- to 4-fold decreased enzyme activity of COMT [23]. Several evidences demonstrated that COMT Val158Met is significantly associated with breast cancer [24], [25]. It is biologically reasonable to hypothesize that women who carry the mutant COMT Met allele may have higher risks of ischemic stroke. In addition to metabolism of estrogen, estrogens exert their effects by binding to specific estrogen receptors α (encoded by ESR1) and β (encoded by ESR2). The human ESR1 gene (OMIM133430) is located on chromosome 6q25, comprising of 8 exons and 7 introns. Considerable studies focusing on ESR1 c.454−397 T/C (rs2234693) and c.454−351 A/G (rs9340799) polymorphisms in intron 1 are most widely discussed, and the studies found that these two SNPs are associated with ischemic stroke [26], [27], cardiovascular disease [28], [29], and atherosclerosis [30].

Since role of estrogen in cerebrovascular pathophysiology and ischemia is an important area of ongoing investigation, to our knowledge, there is no study focusing on both the estrogen metabolism and signaling pathway genes. The present study was carried out with the aim to determine whether SULT1E1 -64G/A, COMT Val158Met, ESR1 c.454−397 T/C and c.454−351 A/G genes are associated with ischemic stroke of the young and to further explore the gene-gene and gene-environment interactions for young ischemic stroke patients.

Methods

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Taipei Medical University and the participated hospitals, including National Taiwan University Hospital, Shuang Ho Hospital, Chi-Mei Medical Center, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, Tri-Service General Hospital, Wanfang Hospital, Lotung Poh-Ai Hospital, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their relatives.

Study Subjects

In this study, there were 305 ischemic stroke subjects aged ≦ 50 years recruited from 2005 to 2010, including 217 males and 88 females. Details of the participants’ enrollment were described elsewhere [31]. In brief, this case-control study was conducted by the Formosa Stroke Genetic Consortium (FSGC) in Taiwan. FSGC is a platform for hospital collaborations on studies related to the molecular biology of cerebrovascular diseases. A standard operation manual of FSGC was established by an expert panel including 5 stroke neurologists and 3 epidemiologists after a series of consensus conferences. All staffs from the participating hospitals were trained on the standard procedure of case enrollment, including structured questionnaire and blood sample collection. All collaborating hospitals participated in the FSGC since 2005. The diagnostic criteria of stroke have been described in previous study [32]. The definition of ischemic stroke is an onset of focal neurological deficit with signs or symptoms persisting longer than 24 hours with or without acute ischemic lesion(s) on brain CT, or with acute ischemic diffusion-weighted imaging lesion(s) on MRI that corresponded to the clinical presentations. TIA is defined as a transient focal neurologic deficit of ischemic causes that resolves within 24 hours. The subtypes of ischemic stroke were categorized according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria [33]. There were 2736 healthy subjects recruited as possible controls, including 1637 individuals from a community-based prospective study of the nutrition health education program in Taipei City [34] and 1099 subjects who underwent physical examinations at TMUH during 2008–2009. All participants were recruited if they agreed to write informed consent. Among them, 53 subjects with prevalent stroke were excluded. 309 subjects were randomly selected as age-matched controls in the remaining 2683 candidates. The distribution of age, gender, education levels were similar between the selected subjects and the remaining candidates.

Data Collection and Assessments

All participants were informed to draw venous blood for biochemical test, including cholesterol (CHOL), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), fasting glucose, and estradiol level. Blood samples were collected when patients were confirmed as ischemic stroke and when controls agreed to participate in the study. Fasting serum CHOL, TG, HDL-C, and glucose concentrations were measured by an automatic analyzer (UniCel DXC 800, BeckMan). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC) was calculated using Friedewald formula [35]. Laboratory assay for estradiol was measured by radio immunoassay (RIA). The lower limit of quantitation of estradiol level was 2 pg/ml. Duplicate samples were included for 10% of the subjects for quality control purposes. Samples were labeled in such a way that laboratory personnel were unaware of the case-control status of the samples and the identity of the duplicates. Log-transformed was done for serum estradiol level to follow a normal distribution before executing association analyses. In this study, high or low serum estradiol level was defined based on the median level of healthy controls which were 1.68 and 1.38 for female and male, respectively. The anthropometrical measurements were assessed by trained technicians. Body mass index (BMI) was defined as the individual’s body weight (kg) divided by square of their height (m2). Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was computed using index of waist circumference divided by the hip circumference. Obesity was defined as waist circumstances ≧80 cm for female and ≧90 cm for male or BMI>27 kg/m2.

DNA Collection and Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-anticoagulated peripheral blood leukocytes by the phenol/chloroform method and then stored at −80°C until use. Genotyping was carried out by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Genotyping assays were performed using standard protocol in a total volume of 40 ul and 1 to 2 ng of sample DNA was used per assay. Genotyping was performed by laboratory technicians blinded to the case-control status. As a quality control, we repeated to validate the genotyping on 10% of the samples and the concordance rate for replicate samples was 100%. The overall genotyping success rates were >98%.

Statistics

The demographic and health characteristics of the study subjects were analyzed using Student’s t-test and the Chi-square test. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) test was assessed by a goodness-of-fit Chi-square test and was performed to examine possible genotyping error for each SNP among controls. Haplotype estimation was restricted to individuals for whom complete genotype data were available across all polymorphic sites, and the highest probability haplotypes estimated using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm of SAS/Genetics 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) were assigned to each study participant. Logistic regression models were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for determining putative high-risk genotypes of each SNP for ischemic stroke. Age, gender, education level, disease history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, obesity, and cigarette smoking status were adjusted in the models as potential confounders. In addition to traditional multiple logistic regression model to explore high-order gene-gene interactions in susceptibility of young ischemic stroke, we also used several statistical approaches, including the multifactor dimensionality reduction (MDR) software (version 2.0 beta) and MDR-permutation testing (MDRPT) software (version 1.0 beta) and classification and regression tree (CART). The MDR method selects important combinations of variables on the basis of entropy measures for evaluating the information gain (IG) associated with attribute interactions [36]. The patterns of entropy recapitulate the main and/or interaction effect for each model. The CART analysis creates a decision tree that depicts how well each genotype variables predicts patient-control status [37]. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS package, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software (version 2.15.0). All statistical tests were based on a two-sided probability.

Results

The basic characteristics of the study subjects are illustrated in Table 1. The average age and the distribution of gender were similar between ischemic stroke patients and healthy controls. Cases had higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking behaviors than controls. Mean BMI, WHR, fasting glucose levels, LDLC, and TG were significantly higher in cases than in controls while HDLC were lower in cases compared to controls. To determine the ischemic stroke risk contribution of SULT1E1, COMT and ESR1, we examined whether the genotypic and allelic distribution of the gene differed between the 305 cases and 309 controls (301 cases and 308 controls had results of complete 4 SNPs). The frequencies of all 4 SNPs in the controls agreed with those expected under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, suggesting that genotyping error was relatively unlikely. The genotype and allelic analysis for the SNPs yielded no significant differences. However, the permutation test and test for trend showed that the polymorphism of COMT Val158Met was significantly associated with young ischemic stroke susceptibility among females. The results are showed in Table 2. We also found that female patients who carried COMT Met alleles had a significantly higher risk of large artery atherosclerosis (data not shown).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of ischemic stroke and healthy controls.

| Characteristic | Stroke patients (n = 305) | healthy Controls (n = 309) | P-value | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.7 | 6.0 | 43.6 | 5.6 | 0.7626 |

| Male, n (%) | 217 | 71.2 | 221 | 71.5 | 0.9896 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 179 | 59.7 | 74 | 24.0 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 88 | 29.1 | 20 | 6.5 | <0.0001 |

| Ever smoking, n (%) | 161 | 54.0 | 120 | 39.1 | 0.0003 |

| Ever drinking, n (%) | 92 | 30.8 | 47 | 15.2 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 25.5 | 4.6 | 24.3 | 3.0 | 0.0003 |

| Waist-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.84 | 0.08 | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, means (SD), mmol/L | 130.1 | 75.3 | 98.9 | 23.1 | <0.0001 |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mmol/L | 1.09 | 0.42 | 1.24 | 0.33 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mmol/L | 3.35 | 1.16 | 3.08 | 0.73 | 0.0034 |

| Triglyceride, mean (SD), mmol/L | 1.90 | 1.46 | 1.57 | 1.16 | 0.0026 |

| Cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/L | 5.04 | 1.47 | 5.04 | 0.90 | 0.9318 |

| Estradiol level, mean (SD)* | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.1728 |

| TOAST, n (%) | |||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 77 | 25.2 | |||

| Small vessel occlusion | 99 | 32.5 | |||

| Cardioembolism | 16 | 5.2 | |||

| Specific pathogenesis | 33 | 10.8 | |||

| Undetermined pathogenesis | 42 | 13.8 | |||

| Missing | 38 | 12.5 | |||

Estradiol level was shown in log transformed value.

Table 2. Genotype and allelic frequencies of the SULT1E1, COMT, and ESR1 genes in ischemic stroke patients and controls and the estimated odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of ischemic stroke risk.

| Total | Female | Male | ||||||||||||||

| Cases/Controls | OR (95% CI) | P-value | P for trend | P for permutation | Cases/Controls | OR (95% CI) | P-value | P for trend | P for permutation | Cases/Controls | OR (95% CI) | P-value | P for trend | P for permutation | ||

| SULT1E1 | GG | 142/150 | 1.0 | 0.1264 | 0.4165 | 42/47 | 1.0 | 0.2258 | 0.6560 | 100/103 | 1.0 | 0.3094 | 0.7692 | |||

| -64G/A | GA | 123/141 | 0.90(0.60–1.36) | 0.6315 | 32/33 | 1.37(0.58–3.26) | 0.4771 | 91/108 | 0.77(0.48–1.24) | 0.2773 | ||||||

| rs3736599 | AA | 36/17 | 3.39(1.60–7.17) | 0.0014 | 13/7 | 3.52(0.91–13.60) | 0.0679 | 23/10 | 3.50(1.35–9.05) | 0.0099 | ||||||

| G allele | 407/441 | 1.0 | 116/127 | 1.0 | 291/314 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| A allele | 195/175 | 1.35(1.00–1.84) | 0.0521 | 58/47 | 1.67(0.91–9.08) | 0.0986 | 137/128 | 1.21(0.85–1.73) | 0.2970 | |||||||

| COMT | GG | 152/179 | 1.0 | 0.0231 | 0.0919 | 38/56 | 1.0 | 0.0033 | 0.0120 | 114/123 | 1.0 | 0.3818 | 0.8459 | |||

| Val158Met | GA | 119/111 | 1.11(0.74–1.67) | 0.6235 | 40/28 | 1.71(0.71–4.15) | 0.2356 | 79/83 | 0.94(0.59–1.52) | 0.8079 | ||||||

| rs4680 | AA | 30/18 | 1.87(0.86–4.05) | 0.1149 | 9/3 | 4.38(0.78–24.65) | 0.0937 | 21/15 | 1.59(0.66–3.80) | 0.3004 | ||||||

| G allele | 423/469 | 1.0 | 116/140 | 1.0 | 307/329 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| A allele | 179/147 | 1.21(0.88–1.67) | 0.2362 | 58/34 | 1.93(1.00–3.76) | 0.0517 | 121/113 | 1.05(0.73–1.52) | 0.7953 | |||||||

| ESR1 | TT | 114/114 | 1.0 | 0.7036 | 0.9901 | 31/32 | 1.0 | 0.7363 | 0.9946 | 83/82 | 1.0 | 0.8157 | 0.9992 | |||

| c.454 -397T/C | TC | 142/157 | 1.00(0.66–1.52) | 0.9895 | 43/44 | 2.33(0.87–6.24) | 0.0913 | 99/113 | 0.87(0.53–1.41) | 0.5622 | ||||||

| rs2234693 | CC | 45/37 | 1.72(0.93–3.19) | 0.0868 | 13/11 | 2.37(0.66–8.59) | 0.1878 | 32/26 | 1.63(0.77–3.39) | 0.1958 | ||||||

| T allele | 370/385 | 1.0 | 105/108 | 1.0 | 265/277 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| C allele | 232/231 | 1.25(0.94–1.58) | 0.1297 | 69/66 | 1.54(0.84–2.80) | 0.1598 | 163/165 | 1.19(0.84–1.68) | 0.3209 | |||||||

| ESR1 | AA | 176/188 | 1.0 | 0.8241 | 0.9992 | 45/56 | 1.0 | 0.2585 | 0.6890 | 131/132 | 1.0 | 0.3624 | 0.8143 | |||

| c.454 -351A/G | AG | 113/98 | 1.18(0.78–1.78) | 0.4334 | 40/28 | 1.89(0.82–4.38) | 0.1365 | 73/70 | 1.01(0.62–1.64) | 0.9641 | ||||||

| rs9340799 | GG | 12/23 | 0.88(0.37–2.10) | 0.7655 | 2/4 | 1.08(0.13–8.69) | 0.9460 | 10/19 | 0.80(0.31–2.11) | 0.6569 | ||||||

| A allele | 465/474 | 1.0 | 130/140 | 1.0 | 335/334 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| G allele | 137/144 | 1.10(0.79–1.54) | 0.5588 | 44/36 | 1.42(0.73–2.76) | 0.3025 | 93/108 | 1.00(0.68–1.47) | 0.9930 | |||||||

OR was adjustment for age, education level, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, and cigarette smoking.

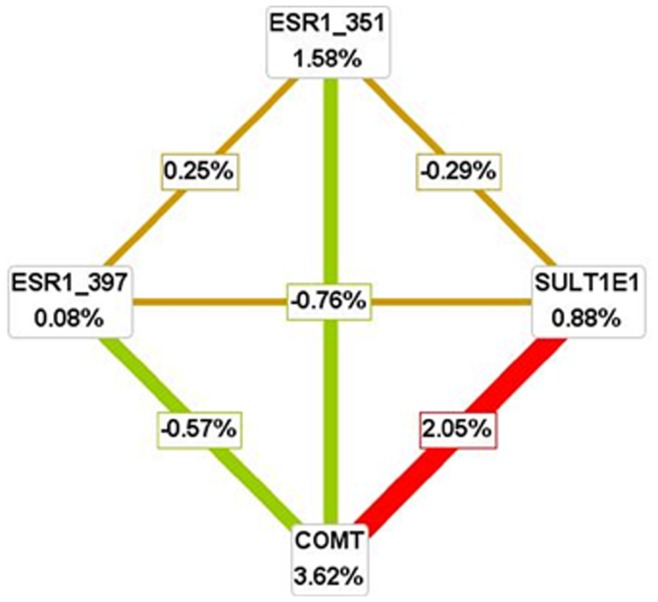

MDR was used to analyze gene-gene interaction models in young ischemic stroke subjects. The two- to four-way gene-gene interaction models are listed in Table 3. The COMT Val158Met and SULT1E1 -64G/A exhibited the highest testing-balanced accuracy and high cross-validation consistency, especially for females. Figure 1 depicts the interaction maps of all genes based on entropy measures among individual variables for female. The strong interaction effect was found among SULT1E1 -64G/A and COMT Val158Met, which had the IG values of 2.05%. The maps for all subjects and males were shown in Figure S1.

Table 3. Summary of MDR gene-gene interaction results.

| Model | Training Bal. Acc. (%) | Testing Bal. Acc. (%) | Cross-validationConsistency | p-value* |

| COMT | 0.5396 | 0.5769 | 7/10 | 0.0140 |

| SULT1E1, COMT | 0.5720 | 0.5722 | 9/10 | 0.0240 |

| COMT, SULT1E1, ESR1 (c.454 -397T/C) | 0.5989 | 0.5951 | 7/10 | 0.0020 |

| SULT1E1, COMT, ESR1 (c.454 -351A/G), ESR1 (c.454 -397T/C) | 0.6279 | 0.5823 | 10/10 | 0.0080 |

| Female | ||||

| COMT | 0.6034 | 0.6264 | 10/10 | 0.0370 |

| SULT1E1, COMT | 0.6507 | 0.6552 | 10/10 | 0.0070 |

| COMT, SULT1E1, ESR1 (c.454 -397T/C) | 0.6865 | 0.6437 | 7/10 | 0.0140 |

| SULT1E1, COMT, ESR1 (c.454 -351A/G), ESR1 (c.454 -397T/C) | 0.7292 | 0.6264 | 10/10 | 0.0370 |

| Male | ||||

| COMT | 0.5364 | 0.5947 | 7/10 | 0.0170 |

| SULT1E1, COMT | 0.5593 | 0.6069 | 6/10 | 0.0050 |

| COMT, SULT1E1, ESR1 (c.454 -397T/C) | 0.5896 | 0.6452 | 6/10 | 0.0010 |

| SULT1E1, COMT, ESR1 (c.454 -351A/G), ESR1 (c.454 -397T/C) | 0.6267 | 0.6137 | 10/10 | 0.0020 |

Interactions were validated based on 1000 permutations.

Figure 1. Interaction map for young ischemic stroke risk among females.

Values in nodes represent information gain (IG) of individual attribute (main effect). Values between nodes are IGs of each pairwise combination of attributes (interaction effects). A positive entropy (plotted in red or orange) indicates interaction while a negative (plotted in green) indicates redundancy.

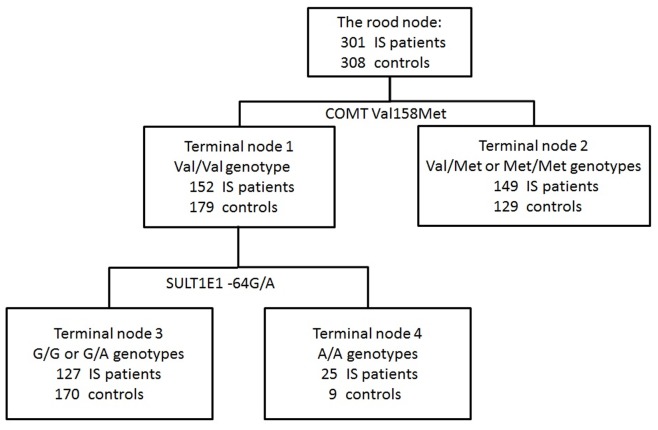

In the CART analysis, the initial split of the root node was COMT Val158Met, indicating that COMT was the strongest risk factor for young ischemic stroke among all the SNPs. Further inspection of the classification tree structure suggested distinct interaction patterns for subjects with Val/Val genotype and Val/Met and Met/Met genotypes. Among participants with Val/Val genotype, SULT1E1 -64G/A is the strongest risk factor, and the combination of COMT Val/Val genotype and SULT1E1 A/A genotype exhibited the highest risk of ischemic stroke with 73.5% patients rate (OR, 6.57; 95%CI, 2.55–16.94; p<0.0001) (Figure 2 and Table 4). In addition, the logistic regression also showed that there was a two-way interaction in Table 4 (for all subjects, p = 0.0171; for female, p = 0.0473). We further analyzed the interaction effect between serum estradiol level and COMT and SULT1E1 genes on young ischemic stroke patients in Table 5. Relative to the reference group that included subjects with high estradiol level and carried COMT Val/Val genotypes and SULT1E1 G alleles, those whose estradiol level was low and carried either COMT Met allele or SULT1E1 A/A genotype had 6.13-fold risk of ischemic stroke, showing a significant joint effect on risk of young ischemic stroke (P for interaction = 0.0174).

Figure 2. Classification and regression tree analysis of polymorphisms of estrogen metabolic and signaling pathway genes.

Table 4. Risk estimate of classification and regression tree terminal nodes.

| Combination of risk genes | Case/Control | OR (95% CI) | P-value | P for interaction | |||

| COMT | Val/Val | SULT1E1 | GG+GA | 127/170 | 1.0 | 0.0171 | |

| AA | 25/9 | 6.57(2.55–16.94) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Val/Met+Met/Met | GG+GA | 138/121 | 1.41(0.92–2.16) | 0.1172 | |||

| AA | 11/8 | 1.51(0.46–4.99) | 0.4990 | ||||

| Female | |||||||

| COMT | Val/Val | SULT1E1 | GG+GA | 29/54 | 1.0 | 0.0473 | |

| AA | 9/2 | 8.9(1.26–63.28) | 0.0286 | ||||

| Val/Met+Met/Met | GG+GA | 45/26 | 2.78(1.11–6.97) | 0.0296 | |||

| AA | 4/5 | 2.37(0.37–15.35) | 0.3647 | ||||

| Male | |||||||

| COMT | Val/Val | SULT1E1 | GG+GA | 98/116 | 1.0 | 0.1845 | |

| AA | 16/7 | 5.17(1.73–15.46) | 0.0033 | ||||

| Val/Met+Met/Met | GG+GA | 93/95 | 1.11(0.68–1.81) | 0.6855 | |||

| AA | 7/3 | 1.58(0.26–9.37) | 0.6192 | ||||

OR was adjustment for age, gender, education level, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, and cigarette smoking.

Table 5. Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the risk of ischemic stroke associated with individual SULT1E1 and COMT and estradiol level.

| Genes | Estradiol level* | ||

| SULT1E1/COMT | High | Low | P for interaction |

| Without risk genotypes | 1.0 | 1.49(0.53–4.23) | 0.0174 |

| With either one risk genotypes | 0.97(0.08–11.43) | 6.13(1.43–26.31) | |

OR was adjustment for age, gender, education level, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, and cigarette smoking.

High estradiol level defined as median log estradiol level was 1.68 and 1.38 for female and male among healthy controls, respectively.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the association between estrogen metabolism and signaling pathway genes, SULT1E1, COMT, and ESR1, and ischemic stroke of the young. The estrogen metabolism genetic polymorphism, COMT Val158Met, was significantly associated with risk of young ischemic stroke among females. Furthermore, we used multianalytic strategies to systemically examine the interaction among these genes. Using different analytic strategy, however, MDR and CART method showed consistent result that there was a strong gene-gene interaction between SULT1E1 -64G/A and COMT Val158Met on the risk of young ischemic stroke. Traditional multiple logistic regression results also showed that there was a significant interaction effect between SULT1E1 -64G/A and COMT Val158Met for development of young ischemic stroke.

Although SULT1E1, a gene encoding an estrogen-metabolizing enzyme, may contribute to individual differences in the biotransformation of this steroid hormone, the relationship between SULT1E1 -64G/A with ischemic stroke was not observed in our study. Owing to low allele frequencies of the three nonsynonymous SNPs among 23 polymorphisms of SULT1E1 identified by Adjei et al. [19], we selected -64G/A located in the promoter region which might influence estrogen sulfotransferase enzyme as the candidate SNPs in our study. We also found that subjects with SULT1E1 -64 G/A AA genotype had significantly lower serum estradiol level than G carriers among healthy controls in our study, especially for females (Table S1). However, the controversial results concerning the association between SULT1E1 -64G/A polymorphism and cancers might be due to the uncertain function of this variant, which might be the reason for non-significant results found in this study [1], [20], [25].

COMT is an important enzyme in the degradation of both catecholamine and estrogens. A non-synonymous G to A base change, COMT Val158Met polymorphism, resulted in the reduction of COMT activity which may impair vascular health in several ways [38], [39]. Several clinical diseases such as preeclampsia [40], hypertension [41], [42] and heart disease [42], [43] have been reported to be associated with this SNP. In addition, growing evidence supports that 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME), a natural estrogen metabolite produced by COMT, has a potent antiproliferative and antiangiogenic capacity [38], [39] and has direct involvement in redox-regulated signaling as a pro-oxidant [44], thus it could be a possible disease mechanism in the protection against atherosclerosis development. Therefore, these abundant studies support our findings that subjects with COMT Met allele had a significant higher risk of young ischemic stroke among females after 1000 permutation tests.

Estrogen influence multiple organ systems including cardiovascular, reproductive and skeletal systems by binding to specific estrogen receptors located within the nuclei of target cells [45]. Numerous epidemiological and experimental studies indicate the protective roles of estrogens in many forms of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [46], [47]. However, most studies have focused on the association between ESR1 variants and cardiovascular disease with conflicting results [27]–[30], [48]–[52], and the reason might owe to various study designs. Although our findings including genotype and haplotype analysis (Table S2 and Table S3) reveal no statistically significant risk for ischemic stroke, a gene-environment interaction effect between ESR1 C-A haplotype and serum estradiol level on young ischemic stroke patients was observed (P for interaction = 0.0348, Table S4). The possible mechanism might be that the transcription factor, ERα, interacts directly with specific promoter sequences comprising 15-bp inverted palindromes known as estrogen response elements (EREs) located in the regulatory region of target genes via binding of 17α-estradiol to their classical receptor ERα 53.

In the present study, the power and the possibility of false positives must be considered. According to a relevant range of minor allele frequencies (22–38%), a post hoc power calculation can reach to near 80% power to detect an effect size (OR) difference of 1.6 using Power and Sample Size Program (version 3.0.43) 54. In addition, multiple testing is a major concern of this study. Genotype and allelic analysis for each of the 4 SNPs yielded no significant association with ischemic stroke of the young after the Bonferroni correction. The excessively conservative correction of the Bonferroni method might result in the decreased power; therefore, based on 10,000 random permutations, the association between risk of young ischemic stroke and COMT Val158Met among females remained significant.

A major strength of our study is that gene-gene interactions were consistently identified by both MDR and CART analysis. The results were also confirmed by logistic regression approach when controlling for confounding variables simultaneously. To improve the statistical power, the MDR method’s conversion from multiple to single variable resulted in efficient identification of potential gene-gene interactions in relatively small samples 55. In addition, the MDR also reduces the chances of making type I errors as a result of multiple testing through cross validation and permutation testing procedure. The CART analysis is a nonparametric strategy, a decision tree-based data mining to identify specific combinations of genetic factors relating to disease, which requires no assumption of a genetic model. Recent researches have suggested that utilizing multiple complementary analytic approaches can increase statistical power to identify possible gene-gene interactions effectively 56.

There were still some limitations in this study. First, the sample size is relatively small due to difficulty in enrollment of young ischemic stroke patients. Thus, further studies in larger populations are required to validate the findings. Second, we used a candidate approach to select SNPs focusing on the functional variants due to limited budget. However, with more advanced genome-wide association studies exploiting the genetic association study, we may have missed some signals that were not genotyped in the current study. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the causal markers in the genes we studied. Finally, the menstrual status was acquired for some subjects when the estradiol level was measured. Therefore the misclassification may have occurred when we included females who were in the ovulation stage in the high estradiol level group as the reference. However, this misclassification is non-differential that might dilute the odds ratio and lead to the result toward the null.

In conclusion, these data indicate that COMT Val158Met polymorphism is significantly associated with ischemic stroke risk among females and suggest that gene-gene interaction effect of SULT1E1 -64G/A and COMT Val158Met polymorphisms play more important roles than the individual factors for the development of young ischemic stroke. Moreover, lower estradiol level could increase risk of young ischemic stroke for those who carried either COMT or SULT1E1 risk genotypes.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Members of the Formosa Stroke Genetic Consortium (FSGC) are:

National Taiwan University Hospital: Jiann-Shing Jeng (Principal Investigator), Sung-Chun Tang, Shin-Joe Yeh, Li-Kai Tsai; Shin Kong WHS Memorial Hospital: Li-Ming Lien (Principal Investigator), Hou-Chang Chiu, Wei-Hung Chen, Chyi-Huey Bai, Tzu-Hsuan Huang, Chi-Ieong Lau, Ya-Ying Wu; Taipei Medical University Hospital: Rey-Yue Yuan (Principal Investigator), Chaur-Jong Hu, Jau- Jiuan Sheu, Jia-Ming Yu, Chun-Sum Ho; Taipei Medical University - Wan Fang Hospital: Chin-I Chen (Principal Investigator), Jia-Ying Sung, Hsing-Yu Weng, Yu-Hsuan Han, Chun-Ping Huang, Wen-Ting Chung; Chi Mei Medical Center: Der-Shin Ke (Principal Investigator), Huey-Juan Lin, Chia-Yu Chang, Poh-Shiow Yeh, Kao-Chang Lin, Tain-Junn Cheng, Chih-Ho Chou, Chun-Ming Yang; Tri-Service General Hospital: Giia-Sheun Peng (Principal Investigator), Jiann-Chyun Lin, Yaw-Don Hsu, Jong-Chyou Denq, Jiunn-Tay Lee, Chang-Hung Hsu, Chun-Chieh Lin, Che-Hung Yen, Chun-An Cheng, Yueh-Feng Sung, Yuan-Liang Chen, Ming-Tung Lien, Chung-Hsing Chou, Chia-Chen Liu, Fu-Chi Yang, Yi-Chung Wu, An-Chen Tso, Yu- Hua Lai, Chun-I Chiang, Chia-Kuang Tsai, Meng-Ta Liu, Ying-Che Lin, Yu-Chuan Hsu; National Cheng Kung University Hospital: Chih-Hung Chen (Principal Investigator), Pi-Shan Sung; Taipei Veterans General Hospital: Chang-Ming Chern (Principal Investigator), Han-Hwa Hu, Wen-Jang Wong, Yun-On Luk, Li-Chi Hsu, Chih-Ping Chung; Lotung Poh Ai Hospital: Hung-Pin Tseng (Principal Investigator), Chin-Hsiung Liu, Chun-Liang Lin, Hung-Chih Lin; Taipei Medical University - Shuang Ho Hospital: Chaur-Jong Hu (Principal Investigator).

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC97-2321-B-038-002, NSC98-2321-B-038-001, and NSC99-2321-B-038-001). Additional support was received from a Ministry of Education Topnotch Stroke Research Center grant and the Department of Health Center of Excellence for Clinical Trial and Research in Neuroscience (DOH99-TD-B-111-003, DOH100-TD-B-111-003, DOH101-TD-B-111-003), and Dr. Chi-Chin Huang Stroke Research Center. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Formosa Stroke Genetic Consortium (FSGC):

Jiann-Shing Jeng, Sung-Chun Tang, Shin-Joe Yeh, Li-Kai Tsai, Shin Kong, Li-Ming Lien, Hou-Chang Chiu, Wei-Hung Chen, Chyi-Huey Bai, Tzu-Hsuan Huang, Lau Chi-Ieong, Ya-Ying Wu, Rey-Yue Yuan, Chaur-Jong Hu, Jau- Jiuan Sheu, Jia-Ming Yu, Chun-Sum Ho, Chin-I Chen, Jia-Ying Sung, Hsing-Yu Weng, Yu-Hsuan Han, Chun-Ping Huang, Wen-Ting Chung, Der-Shin Ke, Huey-Juan Lin, Chia-Yu Chang, Poh-Shiow Yeh, Kao-Chang Lin, Tain-Junn Cheng, Chih-Ho Chou, Chun-Ming Yang, Giia-Sheun Peng, Jiann-Chyun Lin, Yaw-Don Hsu, Jong-Chyou Denq, Jiunn-Tay Lee, Chang-Hung Hsu, Chun-Chieh Lin, Che-Hung Yen, Chun-An Cheng, Yueh-Feng Sung, Yuan-Liang Chen, Ming-Tung Lien, Chung-Hsing Chou, Chia-Chen Liu, Fu-Chi Yang, Yi-Chung Wu, An-Chen Tso, Yu- Hua Lai, Chun-I Chiang, Chia-Kuang Tsai, Meng-Ta Liu, Ying-Che Lin, Yu-Chuan Hsu, Chih-Hung Chen, Pi-Shan Sung, Chang-Ming Chern, Han-Hwa Hu, Wen-Jang Wong, Yun-On Luk, Li-Chi Hsu, Chih-Ping Chung, Hung-Pin Tseng, Chin-Hsiung Liu, Chun-Liang Lin, Hung-Chih Lin, and Chaur-Jong Hu

References

- 1. Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Miller VM, Shuster LT, Brown RD Jr (2012) Premature menopause or early menopause and risk of ischemic stroke. Menopause 19: 272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossouw JE (2002) Hormones, genetic factors, and gender differences in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 53: 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spyridopoulos I, Sullivan AB, Kearney M, Isner JM, Losordo DW (1997) Estrogen-receptor-mediated inhibition of human endothelial cell apoptosis. Estradiol as a survival factor. Circulation 95: 1505–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krasinski K, Spyridopoulos I, Asahara T, van der Zee R, Isner JM, et al. (1997) Estradiol accelerates functional endothelial recovery after arterial injury. Circulation 95: 1768–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iafrati MD, Karas RH, Aronovitz M, Kim S, Sullivan TR Jr, et al. (1997) Estrogen inhibits the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor alpha-deficient mice. Nat Med 3: 545–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lisabeth LD, Beiser AS, Brown DL, Murabito JM, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. (2009) Age at natural menopause and risk of ischemic stroke: the Framingham heart study. Stroke 40: 1044–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baba Y, Ishikawa S, Amagi Y, Kayaba K, Gotoh T, et al. (2010) Premature menopause is associated with increased risk of cerebral infarction in Japanese women. Menopause 17: 506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen DB, Bird IM, Zheng J, Magness RR (2004) Membrane estrogen receptor-dependent extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway mediates acute activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen in uterine artery endothelial cells. Endocrinology 145: 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hisamoto K, Ohmichi M, Kurachi H, Hayakawa J, Kanda Y, et al. (2001) Estrogen induces the Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 276: 3459–3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morales DE, McGowan KA, Grant DS, Maheshwari S, Bhartiya D, et al. (1995) Estrogen promotes angiogenic activity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro and in a murine model. Circulation 91: 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller VT, LaRosa J, Barnabei V, Kessler C, Levin G, et al. (1995) Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. JAMA 273: 199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Valk-de Roo GW, Stehouwer CD, Meijer P, Mijatovic V, Kluft C, et al. (1999) Both raloxifene and estrogen reduce major cardiovascular risk factors in healthy postmenopausal women: A 2-year, placebo-controlled study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 2993–3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walsh BW, Kuller LH, Wild RA, Paul S, Farmer M, et al. (1998) Effects of raloxifene on serum lipids and coagulation factors in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA 279: 1445–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adjei AA, Weinshilboum RM (2002) Catecholestrogen sulfation: possible role in carcinogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 292: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Falany CN, Krasnykh V, Falany JL (1995) Bacterial expression and characterization of a cDNA for human liver estrogen sulfotransferase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 52: 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang H, Varlamova O, Vargas FM, Falany CN, Leyh TS (1998) Sulfuryl transfer: the catalytic mechanism of human estrogen sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem 273: 10888–10892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aksoy IA, Wood TC, Weinshilboum R (1994) Human liver estrogen sulfotransferase: identification by cDNA cloning and expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 200: 1621–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Her C, Aksoy IA, Kimura S, Brandriff BF, Wasmuth JJ, et al. (1995) Human estrogen sulfotransferase gene (STE): cloning, structure, and chromosomal localization. Genomics 29: 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adjei AA, Thomae BA, Prondzinski JL, Eckloff BW, Wieben ED, et al. (2003) Human estrogen sulfotransferase (SULT1E1) pharmacogenomics: gene resequencing and functional genomics. Br J Pharmacol 139: 1373–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirata H, Hinoda Y, Okayama N, Suehiro Y, Kawamoto K, et al. (2008) CYP1A1, SULT1A1, and SULT1E1 polymorphisms are risk factors for endometrial cancer susceptibility. Cancer 112: 1964–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rebbeck TR, Troxel AB, Wang Y, Walker AH, Panossian S, et al. (2006) Estrogen sulfation genes, hormone replacement therapy, and endometrial cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 98: 1311–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu BT, Conney AH (1998) Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells: review and perspectives. Carcinogenesis 19: 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lachman HM, Papolos DF, Saito T, Yu YM, Szumlanski CL, et al. (1996) Human catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacogenetics 6: 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He XF, Wei W, Li SX, Su J, Zhang Y, et al.. (2012) Association between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 30,199 cases and 38,922 controls. Mol Biol Rep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Udler MS, Azzato EM, Healey CS, Ahmed S, Pooley KA, et al. (2009) Common germline polymorphisms in COMT, CYP19A1, ESR1, PGR, SULT1E1 and STS and survival after a diagnosis of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 125: 2687–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Munshi A, Sharma V, Kaul S, Al-Hazzani A, Alshatwi AA, et al. (2010) Estrogen receptor alpha genetic variants and the risk of stroke in a South Indian population from Andhra Pradesh. Clin Chim Acta 411: 1817–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shearman AM, Cooper JA, Kotwinski PJ, Humphries SE, Mendelsohn ME, et al. (2005) Estrogen receptor alpha gene variation and the risk of stroke. Stroke 36: 2281–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shearman AM, Cupples LA, Demissie S, Peter I, Schmid CH, et al. (2003) Association between estrogen receptor alpha gene variation and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 290: 2263–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schuit SC, Oei HH, Witteman JC, Geurts van Kessel CH, van Meurs JB, et al. (2004) Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA 291: 2969–2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lehtimaki T, Kunnas TA, Mattila KM, Perola M, Penttila A, et al. (2002) Coronary artery wall atherosclerosis in relation to the estrogen receptor 1 gene polymorphism: an autopsy study. J Mol Med (Berl) 80: 176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsieh YC, Seshadri S, Chung WT, Hsieh FI, Hsu YH, et al. (2012) Association between genetic variant on chromosome 12p13 and stroke survival and recurrence: a one year prospective study in Taiwan. J Biomed Sci 19: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsieh FI, Lien LM, Chen ST, Bai CH, Sun MC, et al. (2010) Get With the Guidelines-Stroke performance indicators: surveillance of stroke care in the Taiwan Stroke Registry: Get With the Guidelines-Stroke in Taiwan. Circulation 122: 1116–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, et al. (1993) Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 24: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsieh YC, Hung CT, Lien LM, Bai CH, Chen WH, et al. (2009) A significant decrease in blood pressure through a family-based nutrition health education programme among community residents in Taiwan. Public Health Nutr 12: 570–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS (1972) Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18: 499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moore JH, Gilbert JC, Tsai CT, Chiang FT, Holden T, et al. (2006) A flexible computational framework for detecting, characterizing, and interpreting statistical patterns of epistasis in genetic studies of human disease susceptibility. J Theor Biol 241: 252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang H, Bonney G (2000) Use of classification trees for association studies. Genet Epidemiol 19: 323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dubey RK, Imthurn B, Jackson EK (2007) 2-Methoxyestradiol: a potential treatment for multiple proliferative disorders. Endocrinology 148: 4125–4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dubey RK, Jackson EK (2009) Potential vascular actions of 2-methoxyestradiol. Trends Endocrinol Metab 20: 374–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roten LT, Fenstad MH, Forsmo S, Johnson MP, Moses EK, et al. (2011) A low COMT activity haplotype is associated with recurrent preeclampsia in a Norwegian population cohort (HUNT2). Mol Hum Reprod 17: 439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Annerbrink K, Westberg L, Nilsson S, Rosmond R, Holm G, et al. (2008) Catechol O-methyltransferase val158-met polymorphism is associated with abdominal obesity and blood pressure in men. Metabolism 57: 708–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hagen K, Stovner LJ, Skorpen F, Pettersen E, Zwart JA (2007) The impact of the catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism on survival in the general population–the HUNT study. BMC Med Genet 8: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Voutilainen S, Tuomainen TP, Korhonen M, Mursu J, Virtanen JK, et al. (2007) Functional COMT Val158Met polymorphism, risk of acute coronary events and serum homocysteine: the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. PLoS One 2: e181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Banerjee S, Randeva H, Chambers AE (2009) Mouse models for preeclampsia: disruption of redox-regulated signaling. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 7: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deroo BJ, Korach KS (2006) Estrogen receptors and human disease. J Clin Invest 116: 561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hanke H, Hanke S, Bruck B, Brehme U, Gugel N, et al. (1996) Inhibition of the protective effect of estrogen by progesterone in experimental atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 121: 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sampei K, Goto S, Alkayed NJ, Crain BJ, Korach KS, et al.. (2000) Stroke in estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient mice. Stroke 31: 738–743; discussion 744. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Kunnas T, Silander K, Karvanen J, Valkeapaa M, Salomaa V, et al. (2010) ESR1 genetic variants, haplotypes and the risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in the Finnish population: a prospective follow-up study. Atherosclerosis 211: 200–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bos MJ, Schuit SC, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, et al. (2008) Variation in the estrogen receptor alpha gene and risk of stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke 39: 1324–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kjaergaard AD, Ellervik C, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Axelsson CK, Gronholdt ML, et al. (2007) Estrogen receptor alpha polymorphism and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and hip fracture: cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies and a meta-analysis. Circulation 115: 861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koch W, Hoppmann P, Pfeufer A, Mueller JC, Schomig A, et al. (2005) No replication of association between estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to myocardial infarction in a large sample of patients of European descent. Circulation 112: 2138–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Markoula S, Xita N, Lazaros L, Giannopoulos S, Kyritsis AP, et al.. (2008) Estrogen receptor alpha gene haplotypes and diplotypes in the risk of stroke. Stroke 39: e172–173; author reply e174. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53. Wise PM, Dubal DB, Wilson ME, Rau SW, Liu Y (2001) Estrogens: trophic and protective factors in the adult brain. Front Neuroendocrinol 22: 33–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr (1998) Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials 19: 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ritchie MD, Hahn LW, Roodi N, Bailey LR, Dupont WD, et al. (2001) Multifactor-dimensionality reduction reveals high-order interactions among estrogen-metabolism genes in sporadic breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet 69: 138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen M, Kamat AM, Huang M, Grossman HB, Dinney CP, et al. (2007) High-order interactions among genetic polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair pathway genes and smoking in modulating bladder cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 28: 2160–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)