Abstract

Rationale: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a complex disease for which the pathogenesis is poorly understood. In this study, we identified lactic acid as a metabolite that is elevated in the lung tissue of patients with IPF.

Objectives: This study examines the effect of lactic acid on myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis.

Methods: We used metabolomic analysis to examine cellular metabolism in lung tissue from patients with IPF and determined the effects of lactic acid and lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH5) overexpression on myofibroblast differentiation and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β activation in vitro.

Measurements and Main Results: Lactic acid concentrations from healthy and IPF lung tissue were determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy; α-smooth muscle actin, calponin, and LDH5 expression were assessed by Western blot of cell culture lysates. Lactic acid and LDH5 were significantly elevated in IPF lung tissue compared with controls. Physiologic concentrations of lactic acid induced myofibroblast differentiation via activation of TGF-β. TGF-β induced expression of LDH5 via hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α). Importantly, overexpression of both HIF1α and LDH5 in human lung fibroblasts induced myofibroblast differentiation and synergized with low-dose TGF-β to induce differentiation. Furthermore, inhibition of both HIF1α and LDH5 inhibited TGF-β–induced myofibroblast differentiation.

Conclusions: We have identified the metabolite lactic acid as an important mediator of myofibroblast differentiation via a pH-dependent activation of TGF-β. We propose that the metabolic milieu of the lung, and potentially other tissues, is an important driving force behind myofibroblast differentiation and potentially the initiation and progression of fibrotic disorders.

Keywords: lactate, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, myofibroblast, lactate dehydrogenase, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The impact of dysregulated cellular metabolism on disease processes is becoming increasingly recognized. Very little is currently known about the role of cellular metabolism as it pertains to lung disease. In this article, we highlight the importance of dysregulated glycolysis in human lung fibroblasts and how this process may potentially contribute to the development and/or progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study adds significant insight into the role of dysregulated cellular metabolism in the development and progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Furthermore, our data highlight lactate dehydrogenase 5 as a potential therapeutic target for pulmonary fibrosis.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), as its name implies, is a disease for which the underlying pathophysiology remains poorly understood. The prevalence of IPF has been estimated to be between 2.9 and 42.7 per 100,000 (1). The mean duration of survival from the time of diagnosis is 2 to 3 years, and there are currently no effective treatments (2). Thus, research into the pathogenesis of this disease is critical.

Metabolomics is an evolving field that identifies metabolites produced in a biological system. The identification of specific metabolite alterations in biological samples from patients with a disease may ultimately highlight specific metabolic pathways that are dysregulated in that disease. This new technique may help determine the etiologies of complex diseases, such as IPF, that to date have not been fully characterized by traditional approaches such as proteomics and genomics.

Although many potential cellular mechanisms have been elaborated, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–induced myofibroblast differentiation, numerous questions regarding the pathophysiology of IPF and TGF-β biology remain unanswered. On a cellular level, TGF-β is a key cytokine responsible for the transformation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, the pathologic cells that generate excess collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins, ultimately leading to scar formation in the lung (3–5). The biology of TGF-β is complex. It is present abundantly in an inactive form that requires cleavage to become biologically active (6–8). TGF-β is known to be activated by heat, enzymatic cleavage, extremes of pH, integrins, and mechanical stretch (8, 9).

In vitro activation of TGF-β is often accomplished at extremes of pH (10). The role of endogenous more physiological pH changes pertaining to TGF-β activation is not well understood. We recently became interested in the role of lactic acid in lung disease after metabolomic analysis of lung tissue of mice exposed to the fibrogenic agent silica demonstrated elevated concentrations of lactic acid in fibrotic lung tissue compared with healthy control mice (11). The finding of an abnormally elevated metabolic byproduct raised the possibility that there was dysregulation in cellular metabolism. Lactic acid is generated in a multistep process during glycolysis ultimately resulting in the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, a reaction catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). This enzyme exists in all cell types and is expressed as five distinct isoenzymes (12). All LDH isoenzymes catalyze a reversible reaction between pyruvate and lactate; however, LDH5 is the primary isoform found in the liver and muscle tissue. It preferentially drives the reaction from pyruvate to lactate (12) and is therefore an enzyme of particular interest when exploring the etiology of elevated concentrations of lactic acid. To date, lactate and LDH have primarily been regarded as biomarkers of anaerobic metabolism and/or hypoxia (13–15). Animal models have demonstrated elevated levels of LDH in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and/or lung tissue of hypoxic mice (16–18). More recently, however, lactate and LDH have been linked with prognosis in the cancer literature, as higher concentrations of lactate and enhanced LDH expression within various tumors have been associated with poorer outcomes (19, 20). There have been relatively few studies evaluating the role of lactate and LDH in the lung, and although hypoxia may regulate LDH, little is known about the interaction of TGF-β, lactate, and LDH.

Our data demonstrate that lactic acid concentrations are elevated in lung tissue from patients with IPF. Furthermore, we hypothesized that in cell cultures incubated with lactic acid, it is not TGF-β production, but rather TGF-β activation via a pH-dependent mechanism, that drives myofibroblast differentiation. The concept that the metabolic milieu may influence, promote, and/or drive the process of fibrosis is novel and has broad implications for the fibrotic mechanisms in many organ systems throughout the body. This study investigates the role of physiologic concentrations of lactic acid on TGF-β activation, myofibroblast differentiation, and pulmonary fibrosis. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in abstract form (22–26).

Methods

Cells and Reagents

Human lung fibroblasts were derived from tissue explants as described (27, 28). Lactic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the media at 1-, 10-, and 20-mM concentrations. Mixing experiments were performed: lactic acid added to media followed by pH adjustment to pH 7.6, addition of pre–pH-adjusted lactic acid to media, and addition of serum to the media after pH adjustment. Cells were cocultured as indicated in figure legends for 72 hours.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

High-resolution 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) metabolomics using the technique of slow magic angle spinning (i.e., 1H-PASS) (29), was used to determine the concentrations of lactic acid in fibroblast cell lysates and in whole lung homogenates from patients with IPF and from healthy control subjects using previously reported procedures (11).

TGF-β Bioassay

Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial cells (American Type Culture Collection CCl-64, Manassas, VA) were cultured as previously described (30). Cells were treated with media containing lactic acid or TGF-β for 22 hours. A colorimetric detection of BrdU (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) incorporation into cells was used to determine relative proliferation (30).

Western Blots

Cell lysates were run on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and examined for expression of α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) (Sigma Aldrich), calponin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), Smad 2/3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), total LDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), LDH5 (Abcam), and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) (Novus, St. Charles, MO). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Abcam) and β-tubulin (Abcam) were used as loading controls as previously described (31).

Immunohistochemistry

Lung tissue was obtained either through biopsy or explantation of lung tissue. All tissue was kept on ice before formalin fixation. Paraffin-embedded human lung tissue sections were prepared as previously described after histopathological confirmation of usual interstitial pneumonia, healthy lung tissue, sarcoidosis, or organizing pneumonia (32). Antigen retrieval was performed using 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 at 95°C for 20 minutes. Antibodies included LDH5 (Abcam), αSMA (Sigma Aldrich), and pancytokeratin (Sigma Aldrich). A nonspecific IgG antibody was used as an isotype control. Secondary antibodies included a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) and an HRP-SA antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Slides were developed using Vector NovoRED (Vector Laboratories Inc.), and counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin.

Immunofluorescence

Primary human lung fibroblasts were cultured to subconfluence on glass chamber slides under standard conditions described above, and slides were prepared using αSMA (Sigma Aldrich) and Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described (33).

Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was isolated from homogenized primary human lung fibroblast cultures as previously described (31). Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed for COL1A and COL3A1 and compared with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Cloning of Flag-LDH5/Transfections

Total RNA was isolated from primary human lung fibroblasts and cDNA prepared as described previously (28). Specific oligo sequences (forward primer: 5′-TCG AGC TCG AGT CCA ATA TGG CAA CTC TAA AGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCC CTC TAG AAA ATT GCA GCT GCT CCT TTT GGA T-3′) for the LDH5 subunit were designed containing unique restriction sites. Restriction enzyme digestion was performed using Xho I and Xba I enzymes. Flag-pcDNA3 was digested with the same enzymes and the ligation reaction was performed using T4-DNA ligase (New England Biolabs Inc, Ipswich, MA). Bacterial transformation was performed using chemical competent Escherichia coli DH5α (Invitrogen). Fugene 6 (Roche) was used for transfection per the manufacturer’s instructions using 2 μg Flag-LDH5 plasmid per well. The HIF1α overexpressing plasmid and dominant negative HIF1α plasmid were acquired from Jia Guo, M.D. (Division of Pulmonary Medicine, University of Rochester), and transfected as previously published (34, 35). LDH5 siRNA (ON-TARGET SMARTpool, Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT) was transfected using Simporter transfection reagent (Millipore, Temecula, CA). A GFP control vector (Lonza, Hopkington, MA) was used for the transfections and yielded an approximate efficiency of 30%.

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as means ± SD. A Student unpaired t test and one-way analysis of variance were used to establish statistical significance using Graph Pad Prism software. NMR spectroscopy data were analyzed using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test and the two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Results were considered significant if P was less than 0.05.

Results

Lactic Acid Concentrations Are Elevated in Lung Tissue from Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis

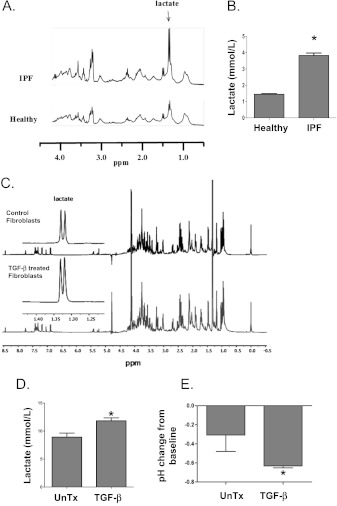

We previously demonstrated that lactic acid concentrations are elevated in the lung tissue of mice exposed to silica compared with control mice (11), and on the basis of these data, we examined whether lactate concentrations were also elevated in the lung tissue of patients with IPF. 1H-PASS NMR spectroscopy of lung tissue homogenates demonstrated that the concentrations of lactic acid were significantly increased in tissue from patients with IPF compared with healthy control subjects (Figures 1A and 1B). We next investigated whether there was a cell-specific increase in lactic acid concentrations. We were particularly interested in the concentrations of lactic acid within myofibroblasts, as fibroblastic foci in the lung tissue of patients with IPF contain fibroblasts differentiated to myofibroblasts. Primary human lung fibroblasts were cultured with 5 ng/mL TGF-β for 72 hours to induce myofibroblast differentiation. High-resolution 1H NMR spectra of cell supernatants showed a significantly higher concentration of lactic acid in myofibroblasts compared with undifferentiated control fibroblasts. The chemical shift peaks for lactate in lung tissue and fibroblasts are labeled in Figures 1A and 1C. The height of the peak represents the quantitative concentration of lactate. Graphic representation of lactate concentrations are shown in Figures 1B and 1D, respectively. Furthermore, the lactic acid generation in fibroblasts induced by TGF-β resulted in a significant decrease in the pH of the media over 72 hours (−0.6 from baseline 7.8) relative to the media of control fibroblast cultures (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Lactic acid concentrations are elevated in pulmonary fibrosis. (A, B) Lactic acid concentrations were measured in whole lung homogenates using 1H-PASS nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy obtained from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (n = 6) and compared with healthy control subjects (n = 6). (C, D) Lactic acid concentrations were measured in primary human lung fibroblast supernatants after treatment with 5 ng/mL transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (n = 3) and compared with untreated controls (n = 3) using high-resolution 1H-PASS NMR. Sample NMR spectra are shown in A and C. The horizontal chemical shift signature of lactate has been labeled accordingly. The height of the peak represents the quantitative concentration of lactate. Quantitative statistical analyses are shown in B and D. (E) The pH of the supernatants from the above cell cultures were measured using a micro pH probe (n = 3 each). *t test, P < 0.05. UnTx = untreated.

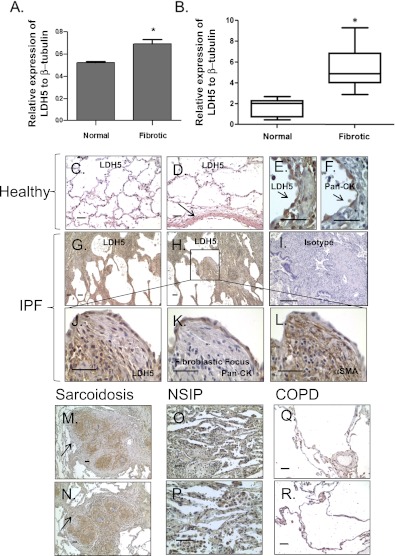

LDH5 Expression Is Elevated in Myofibroblasts Compared with Fibroblasts and in the Lung Tissue of Patients with IPF Compared with Healthy Control Subjects and Subjects with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Given our data (Figure 1) showing elevation of lactic acid concentrations in myofibroblasts and in the lung tissue of patients with IPF, we first examined the expression of the enzymes responsible for the generation of lactate, specifically total LDH and the isoenzyme LDH5. LDH5 is not highly expressed in healthy lung tissue but is abundantly found in liver and skeletal muscle, where it preferentially converts pyruvate to lactic acid, particularly during periods of anaerobic respiration. LDH5 expression measured by Western blot was significantly increased in fibrotic primary human lung fibroblasts compared with healthy control fibroblasts (Figure 2A). We next measured the expression of LDH5 in whole lung homogenates from patients with IPF and compared them to healthy control subjects. LDH5 expression was significantly increased in the lung tissue of patients with IPF compared with healthy lung tissue (Figure 2B). To better define localization of LDH5 expression in IPF lung tissue, we performed immunohistochemistry for LDH5 on lung tissue obtained from healthy patients (n = 6) and patients with IPF (n = 6). We also examined the expression of LDH5 in the lung tissue of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 6) (a hypoxia-related control) and in two other lung diseases associated with fibrosis: sarcoidosis (n = 6) and organizing pneumonia (n = 5). Low levels of LDH5 expression were present in healthy lung tissue (Figures 2C–2F) and localized most prominently to blood vessels (arrow, Figure 2D) and epithelium (Figures 2E and 2F). LDH5 expression was significantly increased in the lung tissue from patients with IPF compared with healthy control subjects (Figures 2G and 2H). In IPF lung tissue, LDH5 expression was diffusely increased but was more prominent in the epithelium overlying the fibroblastic foci, in cells immediately adjacent to myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci, and in fibroblasts in fibroblastic foci (Figures 2J–2L). LDH5 expression was also increased in sarcoidosis (Figures 2M and 2N) and organizing pneumonia (Figures 2O and 2P) but was not significantly elevated in lung tissue obtained from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Figures 2Q and 2R).

Figure 2.

Lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH5) expression is elevated in fibroblasts and lung tissue from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). LDH5 expression was measured by Western blot on protein lysates from (A) primary human lung fibroblasts isolated from both healthy control subjects and fibrotic lung tissue (*t test, P < 0.05; n = 4 each), and (B) whole lung lysates from patients with IPF and healthy control subjects (*t test, P < 0.05; n = 7 each). Immunohistochemistry for LDH5 was performed on lung tissue sections from healthy control subjects (n = 6) and from patients with IPF (n = 6). Reference bars in each panel represent 50 μM. Representative data are shown from two patients each of (C, D) healthy and (G, H) IPF. Additionally, immunohistochemistry was performed on lung tissue from patients with sarcoidosis (M, N) (n = 6), NSIP (O, P) (n = 3), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Q, R) (n = 6). (I) Isotype control. Serial sections of lung tissue from healthy control subjects (E, F) and patients with IPF (J–L) were stained with LDH5, pancytokeratin (an epithelial marker), and/or αSMA (a marker of smooth muscle and myofibroblasts). In healthy lung tissue, LDH5 primarily colocalized in blood vessel walls (arrow, D) and with pancytokeratin (arrows, E and F). In IPF lung tissue, LDH5 expression was diffusely increased but was more prominent in the epithelium overlying the fibroblastic foci, in cells immediately adjacent to myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci, and in fibroblasts in fibroblastic foci (G, H). Notably, there was also increased staining in cells immediately adjacent to fibroblast foci and colocalization with αSMA in fibroblastic foci (J–L). LDH5 expression in sarcoidosis localizes prominently to areas of granulomatous inflammation (arrows, M and N). There is also a diffuse increase in LDH5 expression in the lung tissue of patients with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (O, P). There was no significant increase in LDH5 expression in COPD lung tissue when compared with healthy control subjects (Q, R).

Lactic Acid Induces Myofibroblast Differentiation

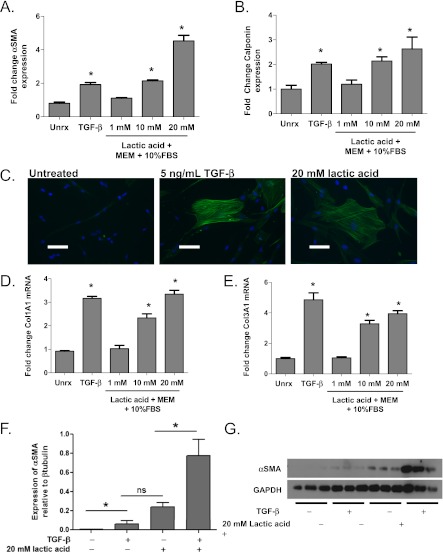

To test the hypothesis that lactic acid induces myofibroblast differentiation in primary human lung fibroblasts, 1-, 10-, and 20-mM concentrations of lactic acid were added to Eagle’s minimum essential medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). These physiologic concentrations of lactic acid ultimately resulted in a rapid change in media pH to 7.2, 6.7, and 6.2, respectively. The pH of the media was adjusted back to pH 7.8 using 1N NaOH before incubation with cell cultures. Myofibroblast differentiation was evaluated by demonstrating elevated expression of αSMA and calponin by Western blot, the hallmarks of myofibroblast differentiation. Extracellular matrix generation was examined by analysis of collagen I and III gene expression by reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Lactic acid induced αSMA and calponin expression in a dose-dependent fashion. Lactic acid at a concentration of 1 mM induced very little myofibroblast differentiation, whereas 10 mM lactic acid induced a similar level of differentiation to that seen with TGF-β alone (Figures 3A and 3B). Lactic acid at 20 mM concentration induced differentiation still further. Immunofluorescent staining for αSMA in primary human lung fibroblasts treated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β or 20 mM lactic acid showed the characteristic smooth muscle filaments of a myofibroblast when compared with cells left untreated (Figure 3C). Similarly, lactic acid induced the collagen I and collagen III gene expression in a dose-dependent fashion with 20 mM lactic acid inducing a maximal response similar to 5 ng/mL TGF-β (Figures 3D and 3E). In addition, the combination of 20 mM lactic acid and low dose TGF-β (1 ng/mL) induced greater expression of αSMA than either 20 mM lactic acid or 1 ng/mL TGF-β alone (Figures 3F and 3G).

Figure 3.

Lactic acid induces myofibroblast differentiation. Primary human lung fibroblasts were cultured with 1, 10, and 20 mM lactic acid for 72 hours. Western blot analysis of protein lysates were performed for markers of myofibroblast differentiation, (A) αSMA and (B) calponin, and compared with cells treated with 5 ng/mL of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (*analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < 0.05 compared with untreated; n = 3 each). (C) Immunofluorescence for αSMA was performed on cell cultures treated with 10 mM and 20 mM lactic acid and was compared with cells treated with TGF-β (scale bars represent 50 μM). (D) Col1A1 and (E) Col3A1 mRNA induction was analyzed on cells 24 hours after treatment with either 1, 10, or 20 mM lactic acid. Results were compared with untreated cells and cells treated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β (*ANOVA, P < 0.05, n = 3 each). (F, G) Fibroblasts were cultured in the presence of both 20 mM lactic acid and low-dose (1 ng/mL) TGF-β for 72 hours. Protein lysates were analyzed for αSMA expression via Western blot. *ANOVA, P < 0.05; n = 3 each. MEM = Eagle’s minimum essential medium; ns = not significant; Unrx = untreated.

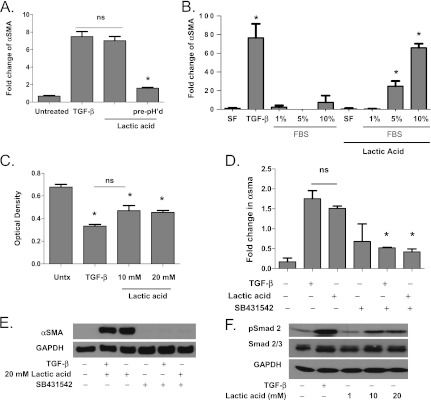

Lactic Acid–induced Myofibroblast Differentiation Is Mediated by the pH-Dependent Activation of Latent TGF-β

Because latent TGF-β is known to be activated by alterations in pH, and because we have shown that the generation of excess lactic acid in the supernatant in fibroblast cell cultures induces acidification of the media, we hypothesized that lactic acid at physiologic concentrations was capable of activating latent TGF-β. To investigate this hypothesis, we first determined that when lactate was added to media at physiologic concentrations determined to be present in the lung tissue of mice and humans (1–20 mM), there was an initial decrease in pH of the media to a pH range between 6.2 and 7.0. The pH was corrected to 7.8 before its incubation with fibroblasts. The addition of lactic acid to media caused dose-dependent induction of myofibroblast differentiation. However, if lactic acid was neutralized to a pH of 7.8 before its addition to the media, so that the pH of the media was unaltered, myofibroblast differentiation did not occur (Figure 4A). We next investigated whether the presence of serum in the media, known to contain latent TGF-β, was necessary for lactic acid to induce myofibroblast differentiation. To start, fibroblasts were cultured in media containing serial dilutions of fetal bovine serum. Lactic acid–induced myofibroblast differentiation did not occur at low serum concentrations (< 5%) or in the absence of serum. More robust differentiation was seen in fibroblasts cultured with 10% FBS compared with 5% FBS (Figure 4B). Fibroblasts cultured with serum-free media containing serial dilutions of latent TGF-β also showed that lactic acid–induced myofibroblast differentiation occurred only in the presence of latent TGF-β (data not shown). These data suggested that decreases in pH of media containing serum caused by physiologic concentrations of lactic acid may lead to the activation of latent TGF-β. To further investigate this hypothesis, TGF-β bioactivity was measured using the mink lung epithelial cell bioassay. Both 10 mM and 20 mM lactic acid suppressed mink lung epithelial cell BrdU incorporation in a similar manner to 5 ng/mL TGF-β (Figure 4C), indicating the presence of bioactive TGF-β. To examine the presence of TGF-β receptor activation, we cocultured primary human lung fibroblasts with 2.5 μM SB431542, a TGF-β receptor–specific serine/threonine kinase inhibitor, and either TGF-β or 20 mM lactic acid. The coincubation of lactic acid and the TGF-β–specific receptor inhibitor inhibited lactic acid–induced myofibroblast differentiation (Figures 4D and 4E). To examine the effects of lactic acid on the TGF-β pathway activation, we next assayed phospho-Smad 2/3 expression. Lactic acid at 20 mM concentration induced phospho-Smad 2 expression in a similar fashion to TGF-β (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Lactic acid induces myofibroblast differentiation in a pH-dependent manner. (A) Human lung fibroblasts were cultured with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, media containing lactic acid in which pH was adjusted after the addition of lactic acid or media containing lactic acid in which the lactic acid solution was pH adjusted before its addition to the media (n = 3 each). Myofibroblast differentiation was assessed by Western blot for expression of α smooth muscle actin (α SMA) (*analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < 0.05 compared with TGF-β and lactic acid). (B) Human lung fibroblasts were cultured in serum free media (SF) and media containing 1%, 5%, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (n = 3 each). Protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for αSMA (*ANOVA, P < 0.05 compared with untreated). (C) Mv1Lu cells were cultured in the presence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β or media containing 10 mM or 20 mM lactic acid for 22 hours (n = 4 each). Cell proliferation was determined by BrdU colorimetric analysis. Diminished BrdU incorporation was indicative of decreased proliferation correlating to enhanced TGF-β bioactivity (*P < 0.05 compared with untreated controls). (D, E) Primary human lung fibroblasts were cocultured with and without SB431542, a specific TGF-β1 receptor inhibitor, 5 ng/mL TGF-β, and 20 mM lactic acid (n = 3 each). Myofibroblast differentiation was assessed by Western blot for expression of αSMA (*ANOVA, P < 0.05 compared with TGF-β and 20 mM lactic acid). (F) Primary human lung fibroblasts were cultured with 5 ng/mL TGF-β or 20 mM lactic acid (n = 3 each). p-Smad 2 and total Smad 2/3 expression were measured by Western blot of whole cell lysates (*ANOVA, P < 0.05 compared with untreated). GAPDH = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns = not significant; Untx = untreated.

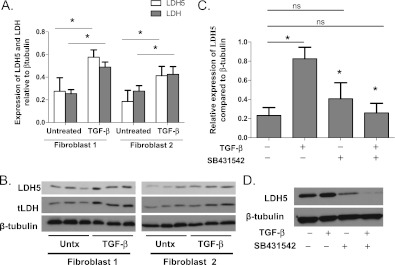

LDH5 Expression Is Regulated by TGF-β

We previously noted that TGF-β induces lactic acid production. We were therefore interested to determine the mechanism(s) through which TGF-β regulates LDH5 expression. Primary human lung fibroblasts were cultured with and without 5 ng/mL TGF-β. Western blot analysis was performed for both total LDH and LDH5. Total LDH and LDH5 were both increased in myofibroblasts compared with untreated fibroblasts (Figures 5A and 5B). Vertical acrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed to examine LDH5 activity. Myofibroblasts exhibited an increase in LDH5 activity that corresponded to the increase in protein levels (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β induces the expression of total lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and LDH5 in primary human lung fibroblasts. (A, B) Fibroblasts were cultured in the presence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β. Western blot analysis of protein lysates was performed for both total LDH and LDH5 expression (*analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < 0.05 compared with control fibroblasts). (C, D) Primary human lung fibroblasts were cultured with and without 2.5 μM SB431542 in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β. Protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for LDH5 expression (*t test, P < 0.05 compared with TGF-β). ns = not significant; Untx = untreated.

To confirm that the increases in LDH and LDH5 expression were directly regulated by TGF-β, fibroblasts were cultured with the TGF-β receptor inhibitor SB431542 in the presence and absence of TGF-β (Figures 5C and 5D). Interruption of the TGF-β signaling pathway with SB431542 inhibited the induction of LDH 5 expression.

LDHA Overexpression Induces Myofibroblast Differentiation and Synergizes with TGF-β to Induce Myofibroblast Differentiation

To examine if increased expression of LDH5 was contributing to myofibroblast differentiation in vitro, we overexpressed LDH5 in primary human lung fibroblasts. Normal primary human lung fibroblasts were transfected with a plasmid containing the LDHA gene, the gene responsible for the production of the M subunit of LDH (LDH5 = 4M). Overexpression of Flag-LDHA induced myofibroblast differentiation compared with untreated fibroblasts, and when LDHA-overexpressing fibroblasts were cocultured with TGF-β, there was a synergistic increase in αSMA expression (Figures 6A–6C) and induction of lactic acid production (Figure 6D). Furthermore, LDH5 suppression using a SMARTpool LDH5siRNA significantly decreased the ability of TGF-β to induce myofibroblast differentiation (Figures 6E and 6F).

Figure 6.

Lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH5) overexpression in primary human lung fibroblasts induces myofibroblast differentiation. Primary human lung fibroblasts were transfected with the Flag-LDHA gene, to overexpress LDH5. (A–C) Fibroblasts overexpressing LDH5 were cultured for 72 hours in the presence and absence of 1 ng/mL transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. Protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of αSMA and calponin. (D) Lactic acid concentrations were measured in the supernatant of primary human lung fibroblasts with and without transfection of an LDHA overexpressing plasmid (**t test, P < 0.001; n = 3 each) (E, F). Fibroblasts were transfected with SMARTpool LDH5 siRNA and were subsequently cultured for 72 hours in the presence and absence of 1 ng/mL TGF-β (n = 3 each). Protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of αSMA. (*Analysis of variance, P < 0.05 compared with untreated.)

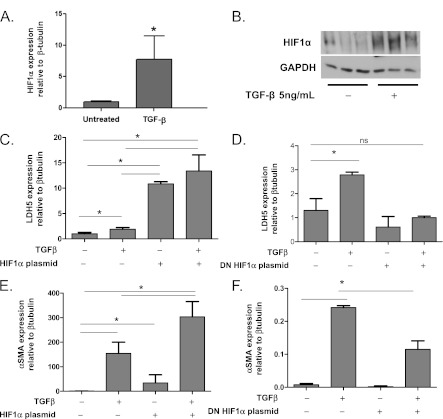

TGF-β Induces HIF1α Expression, and HIF1α Overexpression Induces LDH5 Expression and Myofibroblast Differentiation

To examine whether TGF-β induced LDH5 expression in human lung fibroblasts via induction of the transcription factor HIF1α, we first treated with TGF-β and demonstrated increased expression of HIF1α (Figures 7A and 7B). We then overexpressed HIF1α using a plasmid vector. LDH5 expression was increased in response to HIF1α overexpression (Figure 7C), and dominant negative plasmid–mediated inhibition of HIF1α in the presence of active TGF-β inhibited TGF-β–induced LDH5 expression (Figure 7D). Furthermore, HIF1α overexpression also induced myofibroblast differentiation in a similar manner to LDH5 overexpression and synergized with TGF-β to induce myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 7E). HIF1α inhibition significantly reduced TGF-β–induced myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) expression and HIF1α overexpression induces myofibroblast differentiation, whereas HIF1α inhibition inhibits TGF-β–induced myofibroblast differentiation. (A, B) Primary human lung fibroblasts were treated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β and expression of HIF1α was assessed by Western blot. (C, E) Human lung fibroblasts were transfected with a HIF1α overexpressing plasmid and treated with 1 ng/mL of TGF-β. Protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of (C) lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH5) and (E) αSMA. (D, F) Human lung fibroblasts were transfected with a dominant negative HIF1α expressing plasmid. Protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of (D) LDH5 and (F) αSMA (*analysis of variance, P < 0.05). GAPDH = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns = not significant.

Discussion

The generation and activation of TGF-β are believed to be key factors in the pathogenesis of IPF. We found only one report that suggested that lactic acid may induce TGF-β production in endothelial/fibroblast cocultures, ultimately resulting in myofibroblast differentiation (21). The mechanism by which TGF-β was increased in these cultures was not elaborated. Ultimately, our novel findings led us to investigate the role of lactic acid in myofibroblast differentiation, the metabolic pathway responsible for the production of lactic acid, and how dysregulation of this metabolic pathway may contribute to the initiation of myofibroblast differentiation and/or progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

In this study we used novel metabolomic analysis of fibrotic lung tissue to demonstrate for the first time that lactic acid is elevated in the lung tissue of patients with IPF well above that of normal control subjects. Lactic acid is also elevated in myofibroblasts compared with untreated primary human lung fibroblasts, and LDH5 expression was associated with an increase in lactic acid and lower pH of cell culture supernatants (Figure 1). Furthermore, the enzyme responsible for generating lactic acid was also elevated in fibroblasts isolated from patients with IPF, in IPF lung tissue, and in fibroblasts treated with TGF-β (Figure 2). We investigated the cell-specific expression of LDH5 in IPF lung tissue using immunohistochemistry on serial histologic sections stained for LDH5, αSMA (a marker of myofibroblasts and smooth muscle), and pancytokeratin (an epithelial marker). LDH5 was diffusely increased in the lung tissue of patients with IPF and, on closer inspection, more prominent in the epithelium overlying the fibroblastic foci, in cells immediately adjacent to myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci, and in fibroblasts in fibroblastic foci. Although the increase in whole lung tissue expression of LDH5 may be the consequence of increased lung cellularity, the increased expression results in the physiologic consequence of an increase in lactic acid. We acknowledge that there are other cells in the lung that prominently express LDH5, including the epithelium and that there may be an important paracrine effect by which lactic acid production in these other cell types may augment or induce myofibroblast differentiation and thereby contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis. We plan to investigate this hypothesis in future experiments.

Our primary goal was to determine if lactic acid may ultimately be the important factor that activates TGF-β and subsequently induces myofibroblast differentiation. Because extremes of pH are known to activate TGF-β, we hypothesized that lactic acid may play a pivotal role in myofibroblast differentiation through the activation of latent TGF-β. We first determined that physiologic concentrations of lactic acid induced myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix generation in a similar manner to TGF-β (Figure 3). This occurred through subtle, more physiologic and biologically relevant alterations in pH. Lactic acid when added to media resulted in a decrease in the pH, and this decrease was necessary and sufficient to induce myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 4A). These changes occurred rapidly after the addition of lactic acid, which contrasts to the more gradual and less dramatic changes in pH noted in the supernatants of cells cultured with TGF-β for 72 hours. Importantly, the decrease in pH caused by the rapid addition of lactic acid to cell culture media (pH 6.2–7.2) is physiologically achievable in vivo and relatively minimal compared with the absolute pH of 2.0 known to activate TGF-β in vitro. Furthermore, the assertion that more chronic, gradual changes in extracellular lactic acid concentrations and pH induce myofibroblast differentiation are supported by the finding that LDH5 overexpression in fibroblasts increased lactic acid production, decreased media pH, and induced myofibroblast differentiation, whereas inhibition of LDH5 using siRNA inhibited lactic acid generation, media acidification, and myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 6).

The presence of serum or latent TGF-β was also necessary for lactic acid to induce myofibroblast differentiation. If lactic acid was added to media containing no serum or latent TGF-β, myofibroblast differentiation did not occur (Figure 4B). Furthermore, lactic acid induced bioactive TGF-β in the mink lung epithelial cell bioassay (Figure 4C). Inhibition of the TGF-β receptor blocked the ability of lactic acid to induce myofibroblast differentiation (Figures 4D and 4E). Further evidence of TGF-β activation was the induction of phospho-Smad 2, a downstream marker of TGF-β signaling (Figure 4F). Although we do not suggest that pH/acidity-related activation of TGF-β is a novel finding, the finding that physiologic concentrations of lactic acid and the resulting physiologic alterations in pH can induce myofibroblast differentiation is critically important and of potential wide significance. There is abundant latent TGF-β in the extracellular space (36, 37), and the routes of activation and degradation in vivo remain an area of active research and debate. Although the mechanisms for pH homeostasis in the lung are also largely unknown, the generation of an extracellular pH between 6.8 and 7.2 is theoretically achievable in vivo, particularly during periods of extreme hypoxia and/or hypotension in which lactic acid concentrations can exceed 20 mM (38). These data highlight the concept that the metabolic milieu of the lung and the resulting physiologic concentrations of metabolic byproducts, both intracellular and extracellular, may drive the process of lung fibrosis.

Our in vitro data confirm the importance of elevated LDH5 expression in IPF and specifically in fibroblasts. We demonstrated that LDH5 expression is increased in healthy primary human lung fibroblasts treated with TGF-β (Figures 5A and 5B). This occurred as a direct consequence of TGF-β, as inhibition of TGF-β inhibited the up-regulation of LDH. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the involvement of TGF-β in the regulation of LDH expression and extracellular pH. Importantly, overexpression of LDH5 in healthy lung fibroblasts induced the production of lactic acid and myofibroblast differentiation and enhanced the ability of low-dose TGF-β to induce myofibroblast differentiation (Figures 6A–6D). Equally important, the inhibition of LDH5 expression inhibited TGF-β–induced myofibroblast differentiation (Figures 6E and 6F).

We further demonstrated that TGF-β induced the transcription factor HIF1α, that LDH5 expression and myofibroblast differentiation were induced by HIF1α overexpression, and that inhibition of HIF1α using a dominant negative plasmid construct inhibited TGF-β–induced LDH5 expression and myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 7).

Our findings provide the basis for a potential feed-forward loop involving lactic acid, TGF-β, HIF1α, and LDH. We propose that lactic acid activates TGF-β, subsequently increasing HIF1α and LDH5 expression, thereby generating additional lactic acid that eventually leads to heightened TGF-β activation. A method to measure pH on a cellular level in the lung in vivo is not currently available; therefore, we are not at present able to confirm that the pH alterations required for TGF-β activation are occurring in human lung tissue. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the elevation in LDH5 and lactic acid may not be specific to usual interstitial pneumonia/IPF. However, the finding of elevated LDH5 expression in other inflammatory/fibrotic lung diseases known to induce scarring (sarcoidosis and organizing pneumonia) does not diminish the conceptual applicability but may rather make the finding more generalizable. Ultimately, inhibition of LDH5 expression or activity may prove to be an important therapeutic target for diseases that currently have few effective therapies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Buswell Medicine Fellowship, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; National Institutes of Health grants HL-075432, HL-66988, HL 088325, and T32 HL066988; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center Grant P30ES01247; Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program Career Development Award; The Connor Fund; The Chandler and Solimano Fund; and award number KL2RR024136 from the National Center for Research Resources. J.Z.H. and N.G.I. were supported by National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources award number 1R21RR025785-01. The nuclear magnetic resonance metabolic profiling experiments were performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the DOE’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Author Contributions: R.M.K.: primary researcher and author; E.L.: data and sample collection, study coordinator; K.A.S.: primary laboratory technician; T.D.: sample preparation, laboratory assistant; R.S.: sample preparation, immunohistochemistry, laboratory assistant; A.A.K.: transfections, polymerase chain reaction data; N.G.I. and J.Z.H.: nuclear magnetic resonance data; S.H.: immunohistochemistry preparation and interpretation, pathologist, sample collection; G.G. and S.D.N. provided lung tissue samples from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; C.J.: sample collection; R.P.P.: manuscript review, scientific study design; P.J.S.: primary mentor, manuscript review.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0084OC on August 23, 2012

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kottmann RM, Hogan CM, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Determinants of initiation and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2009;14:917–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sime PJ, Xing Z, Graham FL, Csaky KG, Gauldie J. Adenovector-mediated gene transfer of active transforming growth factor-beta1 induces prolonged severe fibrosis in rat lung. J Clin Invest 1997;100:768–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartram U, Speer CP. The role of transforming growth factor beta in lung development and disease. Chest 2004;125:754–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly M, Kolb M, Bonniaud P, Gauldie J. Re-evaluation of fibrogenic cytokines in lung fibrosis. Curr Pharm Des 2003;9:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wipff PJ, Hinz B. Integrins and the activation of latent transforming growth factor beta1 - an intimate relationship. Eur J Cell Biol 2008;87:601–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalil N. TGF-beta: From latent to active. Microbes Infect 1999;1:1255–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aluwihare P, Munger JS. What the lung has taught us about latent TGF-beta activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:499–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci 2003;116:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence DA, Pircher R, Jullien P. Conversion of a high molecular weight latent beta-TGF from chicken embryo fibroblasts into a low molecular weight active beta-TGF under acidic conditions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1985;133:1026–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu JZ, Rommereim DN, Minard KR, Woodstock A, Harrer BJ, Wind RA, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Metabolomics in lung inflammation:A high-resolution (1)h NMR study of mice exposed to silica dust. Toxicol Mech Methods 2008;18:385–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drent M, Cobben NA, Henderson RF, Wouters EF, van Dieijen-Visser M. Usefulness of lactate dehydrogenase and its isoenzymes as indicators of lung damage or inflammation. Eur Respir J 1996;9:1736–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lott JA, Stang JM. Serum enzymes and isoenzymes in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of myocardial ischemia and necrosis. Clin Chem 1980;26:1241–1250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valentine WN, Tanaka KR, Paglia DE. Hemolytic anemias and erythrocyte enzymopathies. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiu RV, Mountantonakis SE, Dunbar AJ, Schreiber MJ., Jr Tumor lysis syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost 2007;33:397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SX, Miller JJ, Stolz DB, Serpero LD, Zhao W, Gozal D, Wang Y. Type I epithelial cells are the main target of whole-body hypoxic preconditioning in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;40:332–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emad A, Emad V. The value of BAL fluid LDH level in differentiating benign from malignant solitary pulmonary nodules. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2008;134:489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossignol F, Solares M, Balanza E, Coudert J, Clottes E. Expression of lactate dehydrogenase a and b genes in different tissues of rats adapted to chronic hypobaric hypoxia. J Cell Biochem 2003;89:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis MI, Pezzella F, Sivridis E, Turley H, Harris AL, Gatter KC. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 expression in non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas is associated with hypoxia regulated proteins. Leuk Lymphoma 2008;49:2181–2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Bougioukas G, Didilis V, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH-5) overexpression in non-small-cell lung cancer tissues is linked to tumour hypoxia, angiogenic factor production and poor prognosis. Br J Cancer 2003;89:877–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid SA, Gaumann A, Wondrak M, Eckermann C, Schulte S, Mueller-Klieser W, Wheatley DN, Kunz-Schughart LA. Lactate adversely affects the in vitro formation of endothelial cell tubular structures through the action of TGF-beta1. Exp Cell Res 2007;313:2531–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kottmann RM, Smolnycki KA, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Physiologic concentrations of lactate activate TGFb in a pH dependent manner and drive myofibroblast differentiation [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010;7:A3521 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kottmann RM, Smolnycki KA, Lyda E, Dahanayake T, Jones C, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Transforming growth factor beta up-regulates lactate dehydrogenase expression in primary human lung fibroblasts: implications for cellular metabolism [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010;7:A3520 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahanayake TM, Smolnycki K, Xu HD, Sime PJ, Kottmann RM. LDH5 expression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010;7:A3503 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kottmann RM, Smolnycki KA, Lyda B, Dahanayake T, Hu JZ, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Metabolomics identifies lactic acid as a potential activator of TGF-β: implications for the contribution of cellular metabolism to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Presented at the International Colloquium on Lung and Airways Fibrosis. October, 2010, Busselton, Australia. Abstract.

- 26.Dahayanake T, Smolnycki KA, Phipps RP, Sime PJ, Kottmann RM. LDH5 expression in organizing pneumonia: lactic acid upregulates IL-6 and PGE-2 expression in primary human lung fibroblasts and FGF and PDGF in human lung epithelial cells [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:A3483 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baglole CJ, Reddy SY, Pollock SJ, Feldon SE, Sime PJ, Smith TJ, Phipps RP. Isolation and phenotypic characterization of lung fibroblasts. Methods Mol Med 2005;117:115–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson HE, Kulkarni A, Lehmann GM, Garcia-Bates TM, Thatcher TH, Huxlin KR, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Electrophilic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands have potent antifibrotic effects in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:722–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wind RA, Hu JZ, Rommereim DN. High-resolution (1)h NMR spectroscopy in organs and tissues using slow magic angle spinning. Magn Reson Med 2001;46:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jurukovski V, Dabovic B, Todorovic V, Chen Y, Rifkin DB. Methods for measuring TGF-b using antibodies, cells, and mice. Methods Mol Med 2005;117:161–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson HE, Kulkarni A, Lehmann GM, Garcia-Bates TM, Thatcher TH, Huxlin KR, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Electrophilic peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma ligands have potent antifibrotic effects in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 200941:722–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Sime PJ, Gauldie J. Proteoglycans decorin and biglycan differentially modulate TGF-beta-mediated fibrotic responses in the lung. Am J Physiol 2001;280:L1327–L1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulkarni AA, Thatcher TH, Olsen KC, Maggirwar SB, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. PPAR-γ ligands repress TGFβ-induced myofibroblast differentiation by targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway: implications for therapy of fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e15909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang BH, Rue E, Wang GL, Roe R, Semenza GL. Dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 1996;271:17771–17778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 1996;16:4604–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gumienny TL, Padgett RW. The other side of TGF-beta superfamily signal regulation: thinking outside the cell. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2002;13:295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu HJ, Burgess AW. Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun 2001;4:321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luft FC. Lactic acidosis update for critical care clinicians. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:S15–S19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.