Abstract

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common neurological disorder of unknown etiology that is managed by therapy directed at relieving its symptoms. Treatment of patients with milder symptoms that occur intermittently may be treated with nonpharmacological therapy but when not successful, drug therapy should be chosen based on the timing of the symptoms and the needs of the patient. Patients with moderate to severe RLS typically require daily medication to control their symptoms. Although the dopamine agonists, ropinirole and pramipexole have been the drugs of choice for patients with moderate to severe RLS, drug emergent problems like augmentation may limit their use for long term therapy. Keeping the dopamine agonist dose as low as possible, using longer acting dopamine agonists such as the rotigotine patch and maintaining a high serum ferritin level may help prevent the development of augmentation. The α2δ anticonvulsants may now also be considered as drugs of choice for moderate to severe RLS patients. Opioids should be considered for RLS patients, especially for those who have failed other therapies since they are very effective for severe cases. When monitored appropriately, they can be very safe and durable for long term therapy. They should also be strongly considered for treating patients with augmentation as they are very effective for relieving the worsening symptoms that occur when decreasing or eliminating dopamine agonists.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0139-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Restless legs syndrome, Dopamine agonists, Ropinirole, Pramipexole, Rotigotine, Gabapentin enacarbil, Opioids, Methadone, Augmentation, Anticonvulsants

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a neurological sensorimotor disorder that is diagnosed based on 4 essential clinical criteria that were established by the International RLS Study Group in 2003 [1]. These criteria are as follows:

An urge to move the legs, usually accompanied or caused by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs (e.g., sometimes the urge to move is present without the uncomfortable sensations, and sometimes the arms or other body parts are involved in addition to the legs).

The urge to move or unpleasant sensations begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity, such as laying or sitting.

The urge to move or unpleasant sensations are partially or totally relieved by movement, such as walking or stretching, at least as long as the activity continues.

The urge to move or unpleasant sensations are worse in the evening or night than during the day, or only occur in the evening or night (when symptoms are very severe; the worsening at night may not be noticeable but must have been previously present).

A fifth criterion has just been established by the International RLS Study Group in 2012 that includes ruling out mimics of RLS (leg cramps, arthritis, neuropathies, claudication, positional discomfort, and so forth) that might confound the diagnosis. Future diagnostic manuals, such as the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), will likely include this fifth diagnostic criterion.

Symptoms are often very difficult for patients to articulate, as there are usually no words to adequately describe the uncomfortable leg sensations that often result in the diagnosis being missed or delayed for many years. Although an overnight sleep study demonstrating increased periodic limb movements (PLM) of >5/h is supportive of the RLS diagnosis, it is not essential (only 80–85 % of RLS patients have increased PLM [2]). Therefore, an overnight polysomnogram is not necessary to establish the diagnosis of RLS, and the absence of PLM does not rule out RLS. Furthermore, increased PLM are present in other sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, in other medical disorders, and in patients treated with certain medications (especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) [3] and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) [4] antidepressants). In questionable cases, a family history of RLS [5] or a clinical response to a dopamine drug (more than 90 % report some relief [1]) may help establish the diagnosis.

RLS is a fairly common disorder with prevalence rates of 4 to 29 % based on a recent review of 34 studies of prevalence rates in North American and Western European populations [6] and 1.6 to 12 % in Asian populations [7–12]. One of the larger American and European studies [13] found that RLS occurred in 7.2 % of the North American and Western European population and that 2.7 % had clinically significant RLS symptoms (occurring at least 2 times per week and reported as moderately or severely distressing). This study also found that RLS had a significant impact on the health of these patients as their Short Form-36 (SF-36) scores were significantly below population norms, matching those of patients with other chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes and clinical depression. As demonstrated by several other studies [14–17], this study confirmed that RLS was twice as common in women compared to men and the prevalence increases up to 80 years old after which it decreases.

Most patients with RLS have idiopathic RLS for which the etiology is still unknown. Because studies have shown that more than 60 % of RLS patients have a family history of the disease [18, 19], there has been an assumed genetic component of this disease and several genome-wide associated studies have found an increased risk for developing RLS and PLM with a few genomic regions (BTBD9, MEIS1, MAP2K5/LBXCOR1, and PTPRD) [20]. Secondary RLS is most often associated with iron deficiency [21, 22], pregnancy [15, 23–26] and end-stage renal failure [27–29]. There is an increase of RLS associated with other neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease [30–33], multiple sclerosis [34], spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 [35], peripheral neuropathies [36–39], essential tremor [40], myelopathies [41], and polyneuropathies [42, 43].

Strategies for the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome

Not all patients with RLS need treatment. Patients with mild disease may not need drug therapy or other interventions, whereas those with severe symptoms may require multiple medical treatments. Similar to the approach for patients with back pain, therapeutic decisions should be based on the frequency and severity of symptoms and the disability that results from them. Several algorithms [44–47] for guiding physicians on how to treat RLS have been developed and they all have fairly similar suggestions, which vary, mostly due to the availability and government approval of medications in the authors’ countries. Recommendations and suggestions for treating RLS in this article are based on 1 of the oldest of these algorithms [44], but they have been updated by currently available medication, interval medical literature, and the author’s clinical experience.

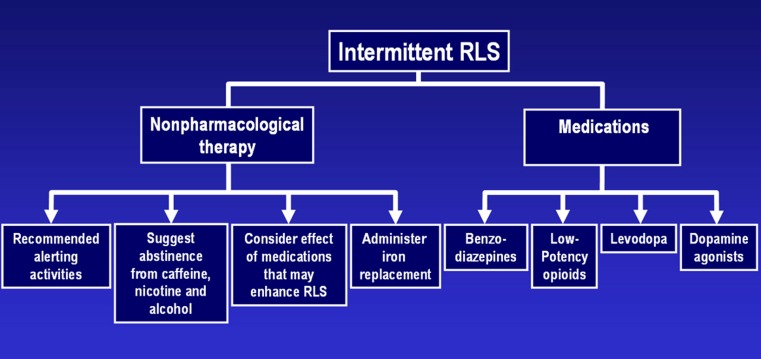

Intermittent RLS

Nonpharmacological Therapy for Intermittent RLS

The majority of patients with intermittent RLS symptoms have mild ones that typically do not require drug therapy. Nonpharmacological remedies are often sufficient to quell these patients’ symptoms.

Alerting Activities

Symptoms characteristically occur when patients are at rest both physically and mentally. Although the preferred activity to relieve symptoms is physical movement (walking, moving the affected limb, massage, and so forth), it is not always possible (e.g., when traveling in an airplane while the “fasten your seat belt” sign is on). Mentally engaging activities, such as playing a video game, solitaire, chess, doing a crossword puzzle, or even having a mentally stimulating conversation can markedly reduce or eliminate RLS symptoms when the patient is sedentary, which is based on hundreds of anecdotal reports to the author and other RLS experts. However, patients report that passive activities, such as watching the in-flight movie provide no relief.

Abstinence from Caffeine, Nicotine, and Alcohol

There is very little evidence in the medical literature supporting worsening of RLS by caffeine and improvement with cessation of its intake. Furthermore, in clinical practice, an adverse response to caffeine is not very commonly seen. The evidence supporting this negative association is based on 1 study [48] performed in 1978 (before the diagnostic criteria for diagnosing RLS was established), in which patients had complete remission of their RLS symptoms after stopping their caffeine intake. This unblinded study had several flaws and has never been replicated. Therefore, whether caffeine truly exacerbates RLS is not very clear, but some patients may benefit from refraining from its intake.

The literature is also not very supportive for the effect of nicotine/tobacco on RLS. An early case report [49] described a 70-year-old patient with severe RLS who had a complete remission of symptoms 1 month after smoking cessation. No significant differences in the incidence of RLS was found in a 1997 epidemiological study [50] between Canadian adult smokers and nonsmokers, whereas 2 other epidemiological studies (1 in 2000 [51] and another in 2004 [52]) both found an increased risk of RLS in smokers. However, in clinical practice, the effect of smoking on RLS has not been very noticeable.

Although based on clinical experience, alcohol consumption tends to exacerbate RLS much more than the 2 substances in this section; the only study to support this link is the 2000 epidemiological study [42], which used telephone interviews on 1803 Kentucky adults. Alcohol is commonly used by RLS sufferers as an easily available hypnotic to help them get to sleep, but in addition to worsening their RLS symptoms, it also increases wakefulness in the second half of the night [53] and leads to disturbed sleep, even with a single low dose resulting in increased sleep fragmentation and number of awakenings in nonalcohol dependent adults [54].

Avoid Medication That May Enhance RLS

This is the most common cause of iatrogenic exacerbation of RLS, although patients often create this problem by taking many of the over-the-counter (OTC) drugs that worsen the syndrome. Most physicians have no knowledge of the long list of drugs that affect RLS and thus frequently prescribe them for RLS sufferers. The mechanism of this exacerbation is not understood, although for some of these drugs it may be related to dopamine blockade because dopamine blocking drugs, such as pimozide [55] typically worsen RLS symptoms.

Antihistamines

Due to their ease of availability, this is 1 of the most common classes of drugs that is bothersome to patients with RLS. There is no medical literature to substantiate this association, but extensive clinical experience supports this effect. These drugs are prevalent in OTC sleeping pills (diphenhydramine, doxylamine) and OTC cold remedies (often in combination with other drugs, which makes their presence even less obvious). Alternatives to their use include the newer second generation H1 blockers (loratadine, fexofenadine, desloratadine, and possibly cetirizine) that do not cross the blood-brain barrier and thus do not worsen RLS symptoms.

Anti-Nausea and Anti-Emetic Drugs

Many anti-nausea drugs (trimethobenzamide, prochlorperazine, promethazine, hydroxyzine, meclizine, and metoclopramide) block the dopamine system and thus may worsen RLS [56]. Alternatives include the newer selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (granisetron hydrochloride, ondansetron hydrochloride), which do not bind to the dopamine receptors [57], and the peripherally acting drug domperidone (not available in the United States [U.S.]), which does not cross the blood-brain barrier and does not affect RLS [58].

Antidepressant Medications

Clinical experience combined with studies in the literature have found that antidepressant drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (such as paroxetine [59], sertraline [60], the tetraclycic antidepressant mirtazapine [61, 62], and the SNRI venlafaxine [63]) aggravate RLS patients. A recent study [64] that prospectively followed 271 patients who were started on second-generation antidepressants (fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram, sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, duloxetine, reboxetine, and mirtazapine) for new onset of RLS symptoms or exacerbation of existing symptoms during the course of 1 year found that 9 % of patients reported RLS problems due to their antidepressant. Mirtazapine causes worsening the most frequently at 28 %, and no problems were noted with reboxetine, whereas the other antidepressants had RLS side effects rates of 5 to 10 %. The RLS problems tended to occur within a few days of starting the medication. In a recent article [65], a critical review of the literature on the effect of drugs on RLS and PLM found that the strongest evidence available for antidepressant-induced RLS for escitalopram, fluoxetine, and mirtazapine and the strongest evidence for antidepressant-induced PLM for citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine, but not for bupropion.

The older tricyclic antidepressants also tend to intensify RLS and PLM [66], but clinical experience suggests that the secondary amine tricyclic antidepressants (desipramine, nortriptyline) may have less of an effect on RLS. Other alternatives that do not worsen RLS include bupropion and trazodone. In fact, there are anecdotal case reports [67, 68] for bupropion relieving RLS symptoms and 1 double-blinded, controlled study [69] that demonstrated a statistically significant improvement of RLS with bupropion at 3 weeks, but not at 6 weeks. In clinical practice, a few patients may find that bupropion helps their RLS, but most just notice that it does not worsen their symptoms.

Despite their exacerbating effect on RLS, antidepressant medications should be continued when they are necessary for severe depression or anxiety, and instead additional RLS treatment should be considered.

Neuroleptic Medications

Many of the drugs in this class decrease dopamine neurotransmission [70], which has been postulated as the reason for their worsening of RLS symptoms. These drugs are well known for causing akathisia, which shares many of the clinical features of RLS [71] and is thought to be derived from similar mechanisms. There are several articles supporting the RLS exacerbating effects of neuroleptic drugs, including olanzapine [72], risperidone and haloperidol [73], and lithium [74]. In clinical practice, exacerbation of RLS by neuroleptic medications is a common occurrence, and when these drugs are used to treat serious psychiatric conditions, it is advisable to continue these drugs and rather step up the RLS treatment as needed.

Iron Replacement Therapy

Karl Ekbom [75, 76], who described RLS and named the disease in 1945, suspected iron deficiency anemia as a possible cause, and found that in open-label studies that oral iron therapy was beneficial. In uncontrolled open-label studies, Nordlander [77] and Parrow and Werner [78] demonstrated that even in the presence of normal iron levels, RLS could be markedly improved or resolved by intravenous iron therapy. In 1994, O’Keeffe et al. [21] reported the benefit of oral iron therapy in an open-label study that was inversely correlated with the serum ferritin level. Patients with ferritin levels <18 mcg/l improved the most, those with levels between 18 mcg/l and 45 mcg/l had an intermediate response, whereas those with levels >45 mcg/l derived little benefit from oral iron therapy. Therefore, oral iron therapy has been recommended for RLS patients with serum levels <45 mcg/l until the more recent double-blind, placebo controlled study by Wang et al. [79] in 2009 demonstrated an improvement of RLS symptoms by oral iron therapy of 325 mg bid for 3 months in patients with a range of ferritin levels between 15 and 75 mcg/l. Furthermore, a recent study [80] performed on Japanese children ages 2 to 14 years, with serum ferritin levels between 9 to 62 mcg/l, showed significant relief in the majority of subjects with oral iron therapy, which generally became noticeable after approximately 3 months of therapy. However, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Davis et al. [81] did not show an improvement with oral iron therapy, despite increases in serum iron saturation and a recent literature review of the iron therapy for RLS [82], which did not find sufficient evidence to prove that iron therapy was beneficial for treating RLS.

Oral iron therapy is usually started with ferrous sulfate 325 mg (65 mg of elemental iron), taken with vitamin C (100 mg 1-2 h before meals 3 times daily). Gastrointestinal problems (constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain) often limit the use of oral iron and the fairly good absorption of iron at low serum ferritin levels (20–30 % with ferritin levels <5 mcg/l) markedly decreases with higher serum ferritin levels (2 % with ferritin levels of 60–80 mcg/l).

Medication Therapy for Intermittent RLS

Benzodiazepines

Despite benzodiazepines being among the first classes of drugs used to treat RLS, it is the author’s opinion (although some RLS experts may disagree) that these drugs do not actually relieve RLS symptoms [83]. They do help RLS patients fall asleep, which is comparable to their use in helping patients with mild back pain fall asleep. Although clonazepam is the first benzodiazepine reported as being beneficial for treating RLS [84], it has a very long half-life of more than 40 hours, which often results in next day sedation. Therefore, shorter acting benzodiazepines, such as temazepam or the more selective benzodiazepine receptor drugs, such as zolpidem or eszopiclone are preferred agents for helping RLS patients fall asleep. Zolpidem (half-life of 2.5 h) is a good choice for patients with mainly sleep onset-related insomnia, whereas zolpidem CR or eszopiclone (half-life of 6 h) may be better for those with sleep onset combined with sleep maintenance problems.

Low Potency Opioids

Opioids have been promoted for treating RLS since the 17th century when Sir Thomas Willis described the syndrome and an effective treatment with laudanum (tincture of opium). Low potency opioids, such as codeine, hydrocodone, and tramadol can be very effective for treating intermittent RLS symptoms during the daytime (as long as they do not cause sedation) or at bedtime. Depending on the drug, relief may begin in approximately 30 to 60 minutes and last for 3 to 6 h.

Levodopa

Akpinar [85] first described the successful use of levodopa in 1982 to treat RLS. However, its adoption as a daily RLS drug resulted in worsening of RLS (called augmentation) in more than 80 % of patients [86], and thus levodopa should only be prescribed on an intermittent basis. This drug can provide relief of RLS symptoms in as fast as 15 minutes when taken on an empty stomach, and is thus suitable for relieving RLS for both daytime and bedtime symptoms. However, symptoms may return in approximately 3 to 4 h.

Dopamine Agonists

Dopamine agonists have been well-established for treating patients with moderate-to-severe RLS symptoms. However, their use for milder, intermittent RLS symptoms is less well-established. Since the onset of action for drugs, such as ropinirole and pramipexole is approximately 1 to 3 h, they are more appropriate for predictable situations that provoke RLS, such as a long airplane trip. Furthermore, their longer duration of action (6–8 h) often enhances their usefulness in these situations. Their major drawback for intermittent use is that when higher doses are needed, these drugs must be slowly titrated to avoid side effects, so that reintroducing them at their effective dose after a hiatus may readily cause side effects.

Summary of Treatment of Intermittent RLS

Choices for treating intermittent RLS symptoms based on when they occur and their frequency is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Treatment of Intermittent RLS

| Type of RLS problem | Suitable drugs |

|---|---|

| Bedtime RLS, infrequent | Carbidopa/levodopa |

| Opioids | |

| Benzodiazepines | |

| Bedtime RLS, ≥4–5 nights per week | Consider daily RLS treatment |

| Daytime RLS, expected | Opioids |

| Carbidopa/levodopa | |

| Dopamine agonists | |

| Daytime RLS, unexpected | Opioids |

| Carbidopa/levodopa |

RLS = restless legs syndrome.

Daily RLS

Dopamine Agonists

As per the algorithm for the treatment of daily RLS symptoms, shown in Figs. 1 and 2 [44], nonpharmacological treatment as previously detailed for intermittent RLS should be instituted prior to drug therapy. During the past decade, non-ergot derived dopamine agonists have been considered as the first-line drugs of choice for patients with moderate-to-severe RLS. Numerous studies have supported the efficacy and safety of both ropinirole [87–92] and pramipexole [93–97], resulting in these 2 drugs being the first ones approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating moderate-to-severe RLS.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for the treatment of intermittent RLS [35]

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for the treatment of daily RLS [35]

Ropinirole and pramipexole both act somewhat similarly on the dopamine receptors and should be taken 1 to 3 h before bedtime or at the onset of symptoms. One or 2 additional doses earlier in the day (at 8-h intervals), although not FDA-approved, are often used to treat patients with more advanced RLS. Dose-related side effects include nausea, sedation, dizziness, hypotension, impulse control disorders, and insomnia, although the nausea may be mitigated largely by taking the medication with food, but this also delays the onset of action by approximately 1 h.

Impulse control disorders (pathologic gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping, compulsive eating, compulsive medication use, and punding) with dopamine drugs used for Parkinson’s disease were first reported by Uitti et al. [98] in 1989, with reports of hypersexuality, and then by Molina et al. [99] in 2000 for pathological gambling. At first it was thought to be a problem that was exclusive to Parkinson’s disease, but it was not long before cases were seen in the RLS population with the first published case reports in 2007 [100]. Patients and their families should be warned as to the potential development of impulse control disorders with dopamine agonists, and they should also be questioned carefully on follow-up visits because patients who develop this side effect typically try very hard to conceal it. Therefore, it is essential that this behavior is found before it results in large financial losses or the termination of relationships with spouses, family, or friends. The impulse control disorder can usually be resolved with a reduction or elimination of the dopamine drug.

The major differences between ropinirole and pramipexole include a shorter duration of action for ropinirole (half-life of 6 h) compared to pramipexole (half-life of 8–12 h), and ropinirole is metabolized in the liver, whereas pramipexole is excreted through the kidneys.

Both of these drugs should be started at their lowest dose (ropinirole at 0.25 mg and pramipexole at 0.125 mg) and increased if necessary every 5 to 7 days by their initial dose until symptoms are controlled. Although the FDA-approved, maximum doses for ropinirole and pramipexole are 4 mg and 0.75 mg, respectively; many physicians exceed this dose, especially when treating daytime symptoms that may require 1 or 2 additional doses per day. However, after 10 to 15 years of experience with these drugs, concerns regarding augmentation of RLS symptoms by these drugs have made many RLS experts rethink the doses used to treat RLS, and even whether these drugs should be first-line drugs of choice for this disease. Due to concerns regarding augmentation of RLS, In the opinion of this author and several other RLS experts, the maximum doses of dopamine agonists should be much lower than the approved FDA doses (such as 0.25 mg for pramipexole and 1 mg for ropinirole). However, augmentation may occur even at the lowest doses of dopamine agonists.

A new dopamine agonist, the rotigotine patch (Neupro, UCB, Inc., Smyrna, GA) has just been approved by the FDA (April 2012) for treating moderate-to-severe RLS, and numerous studies support its efficacy and safety [101–106]. The patch is available in 1 mg, 2 mg, and 3 mg per 24-h doses and should be started at 1 mg/24 h and then increased on a weekly basis as needed to a maximum dose of 3 mg/24 h. Although many patients with moderate-to-severe RLS complain predominately of evening and/or bedtime symptoms, most have daytime symptoms that become bothersome when trying to perform sedentary activities or tasks, and would thus benefit from this medication. Furthermore, there is some evidence [107] that augmentation problems may be less frequent and less severe than with ropinirole and pramipexole, but further longer term studies are necessary to fully determine this issue. Side effects are otherwise similar to the other dopamine agonists, with the exception of the most common side effect of the patch, which is skin reactions at the application site; the patch should be rotated on a daily basis.

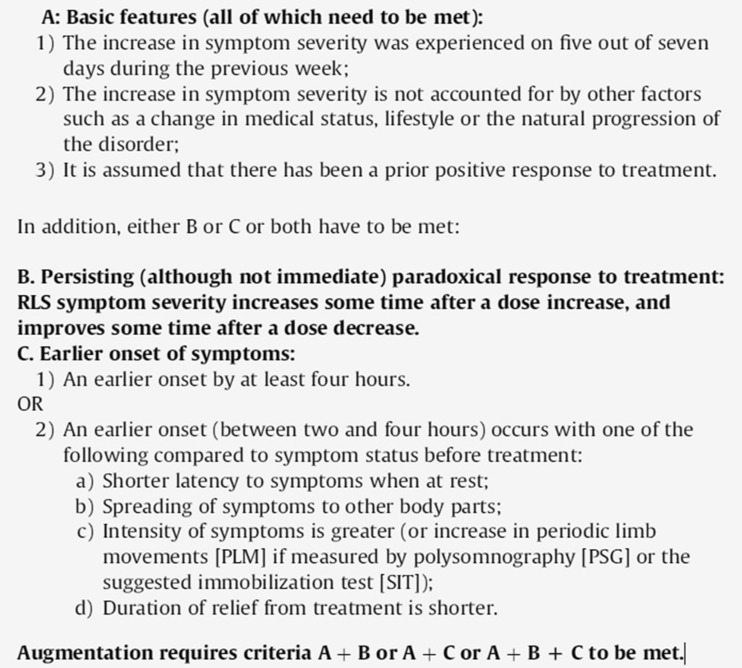

Augmentation

This phenomenon results in a worsening of RLS symptoms that was first described by Allen in 1996 [70] for the use of carbidopa/levodopa and typically occurs only with the use of dopaminergic drugs; there are also reports of augmentation associated with the nondopaminergic drug tramadol [108, 109]). After several weeks, months, or even years, the RLS symptoms become more intense and the latency to symptoms when at rest is shorter; symptoms occur earlier in the day (typically at least 2 h earlier) and return sooner after taking the medication and may spread to other parts of the body. With time, the RLS symptoms can become extremely severe, causing severe insomnia and preventing the patient from remaining sedentary for more than a few minutes. Increasing the medication provides relief for weeks or months, but ultimately just “adds fuel to the fire,” which in the author’s experience is unfortunately the most common treatment followed by most general physicians and even specialists.

The formal criteria for diagnosing augmentation (Max Planck Institute Criteria [110]) are described in Fig. 3 and should be helpful as a guide for diagnosis, but strict adherence to these criteria are more useful for clinical medical trials rather than for clinical practice. The cause of this augmentation problem is unknown, but it presents a common problem in RLS patients, especially those who are treated with higher doses of dopamine agonists. Currently, severe augmentation cases comprise approximately 75 % of consultations performed by RLS experts. A recent study by Silver et al. [111] found that after 10 years approximately 70 % of patients with severe RLS on pramipexole (mean dose, 1.3 mg) discontinued their medication due to augmentation. The frequency of augmentation in clinical practice with less severe patients is likely much lower and has yet to be fully determined, but this is clearly a very significant issue and patients should be closely observed for any signs of this problem.

Fig. 3.

Max Planck Institute criteria

Patients with mild augmentation usually present with symptoms that occur a few hours earlier than prior to being started on their dopamine agonist, and these patients may be treated by receving their medication earlier (1–2 h before the new earlier onset time of symptoms). The dose may have to be increased to cover nighttime/sleep RLS symptoms or a split dose (1 before symptom onset and another at bedtime) to provide complete RLS coverage. However, the total dose should be kept as low as possible to prevent further problems with augmentation. These patients should have their ferritin levels maintained as high as possible because augmentation has been associated with low ferritin levels [112, 113].

For RLS patients with severe augmentation, based on clinical experience, the dopamine agonist usually should be stopped or significantly reduced. The medication can be tapered down slowly or can be stopped abruptly. In either case, a potent opioid (methadone, oxycodone, and so forth) should be prescribed to cover the marked worsening of RLS symptoms, which will predictably occur with the withdrawal of the dopamine drug. This exacerbation of symptoms typically abates within a few weeks or months of stopping the dopamine agonist, at which time the opioids may be reduced. Anticonvulsant drugs (discussed as follows) may be added to further reduce or eliminate the need for opioids.

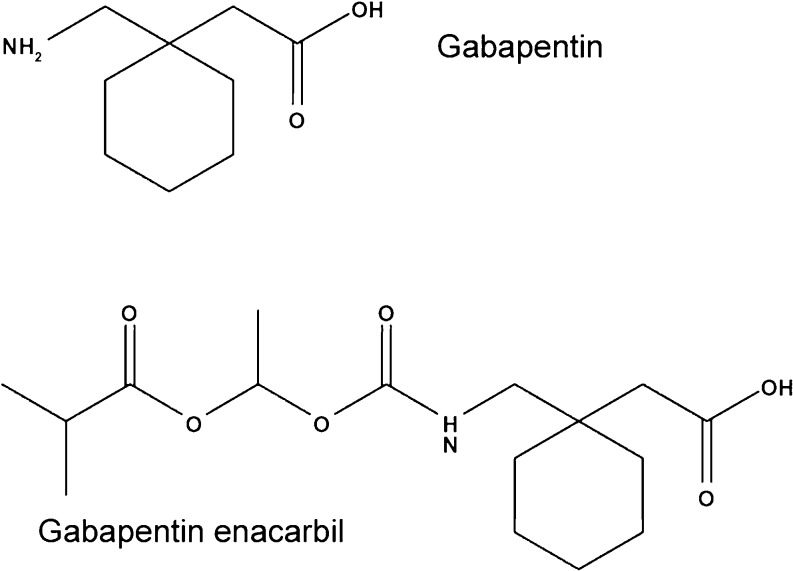

α2δ Anticonvulsants

Mellick and Mellick [114] was the first to publish a study supporting the use of gabapentin for treating RLS in 1996. Since then, other anticonvulsants have been studied and used to treat RLS. In 2011, gabapentin enacarbil, a prodrug of gabapentin became the first nondopamine drug to be approved for RLS in the U.S. Although previous RLS treatment algorithms have typically considered dopamine agonists as the drug of choice for moderate-to-severe RLS patients, anticonvulsants are challenging this paradigm. The α2δ anticonvulsants may now be considered as a comparable first-line treatment for RLS patients and for certain patients, they may be even a better first choice. The anticonvulsant drugs help treat painful RLS symptoms, neuropathy (especially painful neuropathy) and the insomnia that is so common with RLS sufferers. Furthermore, there are no concerns regarding augmentation that is common with dopamine drugs or tolerance, and dependence that may occur with opioid therapy. The most effective and studied anticonvulsant drugs for RLS are the ones that bind to the α2δ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels in the CNS (gabapentin, gabapentin-related drugs, and pregabalin). The α2δ drugs share common side effects that include sedation and dizziness, whereas the class side effect of suicidal ideation and but is a serious concern with these drugs.

Gabapentin

As previously noted, this drug was first studied for RLS in 1996 with many further studies supporting its benefits for RLS in patients with normal renal function [115–119] and for dialysis patients [120, 121]. When treating RLS, it is reasonable to start with 300 mg taken 2 to 3 h before bedtime or before the onset of symptoms for patients up to 55-years-old. A decrease in the initial dose to 200 mg for patients between 55 and 70 years of age and to 100 mg for patients older than 70 years of age is prudent to minimize the emergence of side effects. The dose may be increased on a weekly basis, if needed, by increments of the initial dose until symptoms are relieved or side effects limit the use of the drug (typically to a maximum of 900–1200/per dose). One or 2 additional doses earlier in the day may be added for patients with more severe RLS who often have daytime symptoms.

One issue unique to gabapentin concerns is its poor absorption by the low capacity transporters located in the proximal section of the small intestine [122]. These transporters are very easily saturated, which results in dose-dependent bioavailability of this drug. At subtherapeutic doses, 60 % bioavailability is likely, whereas this reduces to 35 % with higher, more therapeutic doses. Furthermore, the expression of this intestinal transporter saturation problem is quite variable among individuals, making it even more difficult to predict dosing.

As previously discussed, gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Research Triangle Park, NC) is the first nondopamine drug approved in the U.S. for treating moderate-to-severe RLS. Many studies [123–129] have demonstrated its effectiveness and safety for RLS patients in North America and Europe, whereas 1 recent study has demonstrated similar results for Japanese patients [130]. This drug is a pro-drug of gabapentin, which possesses a side chain (see Fig. 4) that permits it to utilize the high capacity transporters present throughout the entire small and large intestines, resulting in dose-proportional oral bioavailability at approximately 70 % across a wide dose range. Once transported into the blood stream, gabapentin enacarbil is rapidly hydrolyzed at the NH bond (see Fig. 4) to form gabapentin.

Fig. 4.

Structure of gabapentin and gabapentin enacarbil

Gabapentin enacarbil is available in 300 and 600 mg extended-release tablets. The 600 mg tablet is for patients with normal creatinine clearances of more than 60 ml/min and should be taken at 5 to 6 pm with food (which is better when absorbed with high-fat content meals). Although this is the only FDA-approved dose for patients with normal renal function, studies [123–127, 129] have shown that some patients do well or better on 1200 mg or even 1800 mg at 5 to 6 pm. There are no studies to support the twice daily use of this drug, but clinical experience has found that some patients with severe RLS and symptoms that start when awakening may benefit from an additional dose in the morning. Dosing for patients with renal impairment should follow the guidelines in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gabapentin enacarbil dosing based on creatinine clearance*

| Creatinine Clearance (ml/min) | Gabapentin enacarbil dose |

|---|---|

| 30–59 | 300 mg daily, increase to 600 mg if needed |

| 15–29 | 300 mg daily |

| <15 | 300 mg every other day |

*Not recommended for dialysis patients

Gabapentin-Extended Release

Gabapentin-extended release (Gralise, Depomed, Inc., Menlo Park, CA) became available in 2011 and is FDA-approved only for treating postherpetic neuralgia. There are no studies and very little clinical experience with this drug for treating RLS. Due to its 24-h extended-release formula, it may be a reasonable choice for patients with severe RLS and symptoms around the clock. This medication uses gastro-retentive technology that causes the tablet to swell in gastric fluids (so it should be taken with food), which keeps the tablet from leaving the upper gastrointestinal tract, where the gabapentin can get absorbed. Although it does not have dose-proportional bioavailability similar to regular gabapentin, due to the slow release of extended-release gabapentin, its range of bioavailability is fairly high. It is available in 300 and 600 mg tablets and should be started at 300 mg and increased every 4 to 7 days by 300 mg until a therapeutic effect is achieved or adverse reactions limit its use (maximum dose, 1800 mg).

Pregabalin

(Lyrica, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals LLC, Vega Baja, PR) is approved for neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and partial seizures. Although only 3 studies [131–133] have demonstrated its efficacy and safety for treating RLS, there is significant clinical experience that has found this drug to be effective for treating RLS. Depending on the patients age, pregabalin may be started at 50 mg (for patients older than 65 years) or 75 mg (for those younger than 65 years) 2 to 3 h before the onset of symptoms or before bedtime. If necessary, this dose may be increased every week by the initial dose until symptoms are resolved. For patients with more severe RLS that starts earlier in the day, an additional dose may be started 2 to 3 h before the onset of their symptoms. The maximum dose should be 300 to 450 mg in the evening and 300 mg for the earlier dose (daily maximum total dosage, 600 mg). Doses should be reduced for patients with renal insufficiency.

Non-α2δ Anticonvulsants

Because the non-α2δ anticonvulsants are generally not as effective as the α2δ anticonvulsants, they have been studied less extensively and have been used much less in clinical practice to treat RLS. However, in cases when the α2δ anticonvulsants are not effective or tolerated, these drugs may at times prove to be worth trying. Some studies have shown a benefit for treating RLS with lamotrigine (open-label study in which 3 of 4 RLS cases benefited from an average of 360 mg) [134], levetiracetam (open-label study showing benefit in 2 cases with augmentation at 500–1000 mg qhs) [135], (open-label study showing benefit in 7 male children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, focal interictal epileptic discharges and RLS) [136], topiramate (open-label, flexible dosing prospective study on 19 patients showing benefit with an average dose of 42 mg) [137], carbamazepine (placebo controlled, double-blind 4-week cross-over study showed that 6 patients did better with 200 mg bid or tid) [138], (placebo controlled, double-blind study on 174 patients showed a benefit with a medium daily dose of 236 mg) [139], oxcarbazepine (3 open-label case reports demonstrating benefit with 300-600 mg) [140], and valproic acid (placebo controlled comparison of slow release valproic acid 600 mg and slow release levodopa/benserazid 200/50 mg showed no difference in efficacy on 20 RLS patients) [141].

Opioids

Opioid therapy is reserved for cases that do not respond adequately to dopamine agonists and anticonvulsants. They are typically not first-line therapy. However, as per the algorithm for treating daily RLS [44], opioids are an excellent choice for patients who do not get full or get any benefit from the other classes of drugs. The opioids can be used as additional therapy to either or both dopamine agonists and anticonvulsants (combination therapy) or can be used alone as monotherapy. The opioids, especially the potent ones, tend to be the most effective RLS drugs, especially for severe RLS cases or for patients who are trying to get off dopamine agonists (particularly in the presence of augmentation).

Most of the effective RLS drugs are in category C or D and thus should be used in pregnant RLS patients only when their benefit outweighs their increased risk to the fetus. However, low-dose opioids (methadone, oxycodone) are in category B and therefore pose less risk to the fetus while being very effective for treating the worsening RLS symptoms that may occur and may worsen especially during the later stages of pregnancy. When possible, the use of drug therapy should be delayed until the third trimester when the risk to the fetus is reduced. When opioids are used during pregnancy, a neonatologist should be involved due to the increased risk of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome.

As previously discussed, the low-potency opioids (codeine, pentazocine, meperidine) or medium-potency opioids (hydrocodone, tramadol) are good choices for “as necessary use” of intermittent mild RLS and should also be considered for patients with daily RLS symptoms who get breakthrough symptoms occurring earlier in the day (as the current FDA-approved drugs are only approved for evening use) or later in the day. For more severe cases or for getting patients off dopamine agonists, the more potent opioids (methadone, oxycodone, levorphanol, morphine, fentanyl, and so forth) are typically necessary. The physician must work closely with the patient to find the lowest dose that relieves RLS symptoms. However, most physicians, even specialists such as neurologists and sleep specialists markedly underuse opioids in these situations in which they are necessary and in which alternative therapy either does not exist or is not as effective.

In 2001, Walters et al. [142] reported on the long-term use of opioid monotherapy for treating RLS in 36 patients at 3 different medical centers. Twenty of the patients continued on opioid monotherapy (tilidine 25 mg and dihydrocodeine 60 mg in Europe, and oxycodone 5 mg, codeine 30 mg, propoxyphene 65 mg, and methadone 10 mg in the U.S.) despite the availability of other treatments and only 1 of the 16 who discontinued opioids did so due to addiction and tolerance. Polysomnogram sleep studies performed on 7 of these patients after an average of 7 years showed a tendency for a decrease in PLM and PLM arousals, as well as an increase in stage 3 and REM sleep, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and a decrease in sleep latency. However, 2 of these patients developed sleep apnea and a third had a worsening of pre-existing sleep apnea.

Many RLS specialists prefer using methadone for severe RLS patients who have failed dopamine agonists and anticonvulsants [143]. Furthermore, Silver et al. [91] found that after 15 % of patients on methadone withdrew from this drug in the first year of therapy due to side effects (similar to pramipexole), no patients withdrew from this therapy for the subsequent 9 years of treatment (compared to 90 % withdrawing from pramipexole for those 9 years). The medium dose of methadone at 6 months was 10 mg and increased by less than 10 mg after 8 to 10 years on this drug.

Side effects with opioids include dizziness, sedation, respiratory depression (caution in patients with sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), nausea, and constipation (many patients will need a stool softener, increased fiber, or even an osmotic agent such as (MiraLax, MSD Consumer Care, Inc., Memphis, TN)). As long as patients have their doses monitored carefully, tolerance and dependence should be easily avoided. It may be necessary to avoid prescribing these drugs to patients with a history of drug abuse. Although methadone has been associated with QT interval prolongation and possible torsades to pointes [144], this typically occurs at much higher doses (>80–200 mg/day) used for heroin addiction therapy compared to the much lower doses used for RLS patients (5–40/day). However, it may be helpful to get an electrocardiogram prior to prescribing methadone to avoid its use in patients with prolonged QT intervals. Electrocardiograms can be performed once a year to follow these patients, and the clinician should be aware of concomitant drugs that may further prolong the QT interval.

Other RLS Treatments

Intravenous Iron Infusion Therapy

As previously noted, Wang et al. [66] demonstrated an improvement in RLS with oral iron in patients with low-normal serum ferritin levels (15–75 mcg/l). However, oral iron does not get absorbed very well,(especially as the serum ferritin increases), and many patients do not tolerate iron due to gastrointestinal side effects. Several studies have demonstrated a benefit from different intravenous iron formulations, including iron dextran 1000 mg [145, 146], iron gluconate 150 mg (x 3 doses) [147], and iron ferric carboxymaltose 500 mg (x 2 doses) [148], but not for iron sucrose 1000 mg [145]. For iron dextran, the low molecular weight preparation should be used as it does not cause anaphylactic reactions [149] and thus also avoids the need for premedication with diphenhydramine, which may exacerbate RLS. The intravenous iron infusion effect can be very dramatic in approximately 60 % of patients, but patients tend to relapse after 3 to 36 months (when serum ferritin levels have typically decreased again), but these patients will respond to subsequent iron infusion therapy. Earley et al. [123] has calculated that RLS patients who respond to intravenous iron therapy have a decline in weekly ferritin levels of 7.7 ± 3.2 mcg/l/week compared to control normal subjects who decrease by <1 mcg/l/week. Iron therapy should be considered for RLS patients with low serum ferritin levels who are failing traditional therapy, especially if they also have anemia. However, the long-term effects of repeated iron infusion therapy in this population have not been studied, so this treatment should be instituted with caution.

Combination Therapy

There are many situations in which combination therapy can make the difference between successful treatment and failure to provide adequate relief for patients suffering from symptoms severe enough to affect their quality of life. Physicians will often completely dismiss medications from their pool of available drugs after they cause an intolerable side effect at their effective dose or if they do not provide adequate relief at their maximum approved dose. Once all the typical drugs have been tried and have failed due to lack of full efficacy or side effects, there may be no obvious course of treatment available. Often, adding failed medications at lower doses together may circumvent the emergence of side effects and their combination may provide effective relief when any of the drugs alone has not been helpful.

In the opinion of the author and several other RLS experts, dopamine agonist dosages should be kept at levels lower than typically recommended (as previously discussed), and instead of increasing the dose when bothersome RLS symptoms persist, adding an anticonvulsant may be a much better solution. If the anticonvulsant provides inadequate relief or causes side effects at higher doses, an opioid may then be added for further management. For patients started on an anticonvulsant, the dose should be increased until limited by side effects or lack of full efficacy, and then a small dose of a dopamine agonist should be added. If further relief is needed, an opioid should then be prescribed.

Physicians should remember that patients often have breakthrough RLS symptoms that are not relieved by their maintenance therapy so patients should be provided with either opioids or carbidopa/levodopa on an as needed basis to take care of those breakthrough RLS symptoms. Furthermore, as insomnia is so prevalent in RLS patients, they should also not forget to provide a hypnotic when necessary to help their patients sleep. Serum ferritin levels should be checked even when there are no signs of iron deficiency anemia, and every effort should be made to raise the serum ferritin >75 mcg/l [79].

Rotation Therapy

Some patients find that after several days or weeks the drug may lose its efficacy or cause adverse effects. Typically, this is more common with dopamine drugs or opioids. Therefore, rotating these drugs every few days or weeks may prove successful.

Marijuana

There are no studies on marijuana for treating RLS, but there is considerable anecdotal evidence from patients as to its effectiveness. Typically, only 1 or 2 puffs of a marijuana cigarette or vaporizer is sufficient to relieve RLS symptoms. It is not clear how long the relief lasts, as most patients use this at bedtime, but they do report the very rapid disappearance of their symptoms, which then helps them fall asleep.

Exercise

There is only 1 study [150] that described the positive benefits of resistance-training exercises performed 3 days per week. Patients very frequently report that regular exercise is helpful for their RLS symptoms and will also use stretching exercises or deep knee bends acutely in an effort to relieve bothersome symptoms. However, vigorous exercise (such as training for a marathon run) often worsens RLS symptoms.

Summary

RLS is a common medical condition and most patients can be successfully treated easily with current FDA-approved medications. Although dopamine agonists have been considered the drug of first choice, many RLS experts think that currently the physicians may select a dopamine agonist or anticonvulsant as their initial treatment.

For patients with more severe RLS or who do not respond adequately to first-line therapy, combination therapy and the use of opioids should be strongly considered. Despite the concerns of tolerance, dependence, addiction, and other side effects, physicians who treat these more advanced RLS cases should be ready to prescribe opioids when necessary or refer the patient to a specialist who is more experienced at treating these difficult cases. When 1 drug in a class fails, others should be tried, and occasionally combination therapy with 3 or more drugs is necessary to provide appropriate relief for challenging cases. When all of the avenues of treatment are explored, almost all RLS patents can be successfully treated.

Augmentation has now become one of the most common causes of treatment failure and is most often misdiagnosed and improperly treated, even by many specialists who see these patients in consultation. Because of this problem, some RLS experts believe that augmentation cases now comprise 75 % or more of their referrals. Although we still do not know how to prevent augmentation, severe augmentation problems might be avoided by keeping the doses of the dopamine agonists as low as possible and by adding iron therapy to raise the serum ferritin level >75 mcg/l. Furthermore, increased awareness of this problem by physicians may enable the diagnosis of augmentation earlier and changes in therapy before the problem becomes severe.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 510 kb)

Acknowledgments

Required author forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article

References

- 1.Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisir J. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–119. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, Lavigne G, Lapierre O, Lespérance P. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: a study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61–65. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorsey CM, Lukas SE, Cunningham SL. Fluoxetine-induced sleep disturbance in depressed patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:437–442. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salín-Pascual RJ, Galicia-Polo L, Drucker-Colin R. Sleep changes after 4 consecutive days of venlafaxine administration in normal volunteers. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:348–350. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen RP, Labuda MC, Becker PM, Earley CJ. Family history study of the restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2002;3:S3–S7. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Agarwal P. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: a synthesis of the literature. Sleep Med. 2011;12:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sevim S, Dogu O, Camdeviren H, et al. Unexpectedly low prevalence and unusual characteristics of RLS in Mersin, Turkey. Neurology. 2003;9(61):1562–1569. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000096173.91554.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taşdemir M, Erdoğan H, Börü UT, Dilaver E, Kumaş A. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in Turkish adults on the western Black Sea coast of Turkey: a door-to-door study in a rural area. Sleep Med. 2010;11:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KW, Yoon IY, Chung S, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the Korean elderly population — results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(1 Pt 1):87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen NH, Chuang LP, Yang CT, et al. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome in Taiwanese adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho YW, Shin WC, Yun CH, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in Korean adults. Sleep. 2008;31:219–223. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J, Choi C, Shin K, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and associated factors in the Korean adult population: the Korean Health and Genome Study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:350–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286–1292. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger K, Eckardstein A, Trenkwalder C, Rothdach A, Junker R, Weiland SK. Iron metabolism and the risk of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population — the MEMO Study. J Neurol. 2002;249:1195–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, John U, Kessler C. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:196–202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Högl B, Kiechl S, Willeit J, et al. Restless legs syndrome: a community-based study of prevalence, severity, and risk factors. Neurology. 2005;64:1920–1924. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163996.64461.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters AS, Hickey K, Maltzman J, et al. A questionnaire study of 138 patients with restless legs syndrome: the ‘Night-Walkers’ survey. Neurology. 1996;46:92–95. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavigne GJ, Montplaisir JY. Restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism: prevalence and association among Canadians. Sleep. 1994;17:739–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raizen DM, Wu MN. Genome-wide association studies of sleep disorders. Chest. 2011;139:446–452. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200–203. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, et al. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1998;21:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman JD, Brodie C, Ayida GA. Restless leg syndrome in pregnancy. Br Med J. 1988;297:1101–1102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6656.1101-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K. Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: the role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:335–341. doi: 10.1089/152460901750269652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manconi M, Govoni V, Vito A, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Medicine. 2004;5:305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pantaleo NP, Hening WA, Allen RP, Earley CJ. Pregnancy accounts for most of the gender difference in prevalence of familial RLS. Sleep Med. 2010;11:310–313. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker S, Fine A, Kryger MH. Sleep complaints are common in a dialysis unit. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:751–766. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkelman JW, Chertow GM, Lazarus JM. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:372–378. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gigli GL, Adorati M, Dolso P, et al. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease. Sleep Med. 2004;5:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan EK, Lum SY, Wong MC. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan PR, Bhatia M, Behari M. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: a case-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2003;18:181–185. doi: 10.1002/mds.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura T, Inoue Y, Miyake M, Yasui K, Nakashima K. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of restless legs syndrome in Japanese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:380–384. doi: 10.1002/mds.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao X, Schwarzschild MA, O’Reilly EJ, Wang H, Ascherio A. Restless legs syndrome and Parkinson’s disease in men. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2654–2657. doi: 10.1002/mds.23256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manconi M, Ferini-Strambi L, Filippi M, et al. Multicenter Case-Control Study on Restless Legs Syndrome in Multiple Sclerosis: the REMS Study. Sleep. 2008;31:944–952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abele M, Burk K, Laccone F, Dichgans J, Klockgether T. Restless legs syndrome in spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, and 3. J Neurol. 2001;248:311–314. doi: 10.1007/s004150170206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polydefkis M, Allen RP, Hauer P, Earley CJ, Griffin JW, McArthur JC. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;55:1115–1121. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merlino G, Fratticci L, Valente M, et al. Association of restless legs syndrome in type 2 diabetes: a case-control study. Sleep. 2007;30:866–871. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gemignani F, Brindani F, Vitetta F, Marbini A, Calzetti S. Restless legs syndrome in diabetic neuropathy: a frequent manifestation of small fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:50–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2007.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boentert M, Dziewas R, Heidbreder A, et al. Fatigue, reduced sleep quality and restless legs syndrome in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: a web-based survey. J Neurol. 2010;257:646–652. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ondo WG, Lai D. Association between restless legs syndrome and essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2006;21:515–518. doi: 10.1002/mds.20746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown LK, Heffner JE, Obbens EA. Transverse myelitis associated with restless legs syndrome and periodic movements of sleep responsive to an oral dopaminergic agent but not to intrathecal baclofen. Sleep. 2000;23:591–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutkove SB, Matheson JK, Logigian EL. Restless legs syndrome in patients with polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:670–672. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199605)19:5<670::AID-MUS20>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gemignani F, Brindani F, Negrotti A, Vitetta F, Alfieri S, Marbini A. Restless legs syndrome and polyneuropathy. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1254–1257. doi: 10.1002/mds.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silber MH, Ehrenberg BL, Allen RP, et al. Medical Advisory Board of the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation. An algorithm for the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:916–922. doi: 10.4065/79.7.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hening WA. Current guidelines and standards of practice for restless legs syndrome. Am J Med. 2007;120(1 suppl 1):S22–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oertel WH, Trenkwalder C, Zucconi M, et al. State of the art in restless legs syndrome therapy: practice recommendations for treating restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2007;22(suppl 18):S466–S475. doi: 10.1002/mds.21545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Borreguero D, Stillman P, Benes H, et al. Algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome in primary care. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lutz EG. Restless legs, anxiety, and caffeinism. J Clin Psychiatry. 1978;39:693–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mountifield JA. Restless legs syndrome relieved by cessation of smoking. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;133:426–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lavigne GJ, Lobbezoo F, Rompre PH, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor or and exacerbating factor for restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism. Sleep. 1997;20:290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips B, Young T, Finn L, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2137–2141. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:196–202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roth T, Roehrs T, Zorick F, Conway W. Pharmacological effects of sedative – hypnotics, narcotics analgesics, and alcohol during sleep. Med Clin North Am. 1985;69:1281–1288. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30987-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rouhani S, Tran G, Leplaindeur F, et al. EEG effects on a single low dose of ethanol on afternoon sleep in the nonalcohol-dependent adult. Alcohol 1989;xx:687-690 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Montplaisir J, Lorrain D, Godabout R. Restless legs syndrome and periodic leg movements in sleep: the primary role of dopaminergic mechanism. Eur Neruol. 1991;31:41–43. doi: 10.1159/000116643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drotts DL, Vinson DR. Prochlorperazine induces akathisia in emergency patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koulu M, Sjoholm B, Lappalinen J, Virtanen R. Effects of acute GR38032F (ondansetron), a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, on dopamine and serotonin metabolism in mesolimbic and nigrostriatal neurons. Eur J Pharmocol. 1989;169:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wetter TC, Stiasny K, Winkelmann J, et al. A randomized controlled study of pergolide in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:944–950. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanz-Fuentenebro FJ, Huidobro A, Tejada-Rivas A. Restless legs syndrome and paroxetine. Ann Psychiatr Scand. 1996;P94:482–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hargrave R, Beckley DJ. Restless leg syndrome exacerbated by sertraline. Psychosomatics. 1998;2:177–178. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teive HA, Quadros A, Barros FC, Werneck LC. Worsening of autosomal dominant restless legs syndrome after use of mirtazapine: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60:1025–1029. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2002000600027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bahk WM, Pae CU, Chae JH, Kim KS. Mirtazapine may have the propensity for developing a restless legs syndrome? A case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56:209–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salin-Pascual RJ, Galicia-Polo L, Drucker-Colin R. Sleep changes after 4 consecutive days of venlafaxine administration in normal volunteers. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:248–350. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rottach KG, Schaner BM, Kirch MH, et al. Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoque R, Chesson AL., Jr Pharmacologically induced/exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and rem behavior disorder/rem sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:79–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garvey MJ, Tolefson GD. Occurrence of myoclonus in patients treated with cyclic antidepressants. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1987;44:429–474. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800150081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee JJ, Erdos J, Wilkosz MF, LaPlante R, Wagoner B. Bupropion as a possible treatment option for restless legs syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:370–374. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, Yang SJ, Shin HY, Yoon JS. Bupropion may improve restless legs syndrome: a report of three cases. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2005;28:298–301. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000194706.61224.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bayard M, Bailey B, Acharya D, et al. Bupropion and restless legs syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:422–428. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.100173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chiodo LA. Dopmine-containing neurons in the mammalian central nervous system: electrophysiology and pharmacology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;12:49–91. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(88)80073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walters AS, Hening W, Rubinstein M, et al. A clinical and polysomnographic comparison of neuroleptic-induced akathisia and the idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1991;14:339–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kraus T, Schuld A, Pollmacher T. Perodic leg movements in sleep and restless legs syndrome probably caused olanzapine. J Clin Psychopharmocol. 1999;19:478–479. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199910000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wetter TC, Brunner J, Bronisch T. Restless legs syndrome probably induced by risperidone treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002;35:109–111. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Terao T, Terao M, Yoshimura R, Kazuhiko A. Restless legs syndrome induced by lithium. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30:1167–1170. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90185-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ekbom K. Restless legs: a clinical study. Acta Med Scand. 1945;121(S158):1–123. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ekbom KA. Restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1960;10:868–873. doi: 10.1212/wnl.10.9.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nordlander NB. Therapy in restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1953;145:453–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parrow A, Werner I. The treatment of restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1966;100:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1966.tb02851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J, O’Reilly B, Venkataraman R, Mysliwiec V, Mysliwiec A. Efficacy of oral iron in patients with restless legs syndrome and a low-normal ferritin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sleep Med. 2009;10:973–975. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mohri I, Kato-Nishimura K, Kagitani-Shimono K, et al. Evaluation of oral iron treatment in pediatric restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med 2012;xx:xx-xx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Davis BJ, Rajput A, Rajput ML, Aul EA, Eichhorn GR. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of iron in restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:70–75. doi: 10.1159/000008138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trotti LM, Bhadriraju S, Becker LA. Iron for restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD007834. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007834.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hening WA, Allen RP, Chokroverrty S, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome. Saunders 2009:272-275.

- 84.Matthews WB. Treatment of the restless legs syndrome with clonazepam. Br Med J. 1979;1:751. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6165.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Akpinar S. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with levodopa plus benserazide. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:739. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510230065027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Allen RP, Earley CJ. Augmentation of the restless legs syndrome with carbidopa/levodopa. Sleep. 1996;19:205–213. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adler CH, Hauser RA, Sethi K, et al. Ropinirole for restless legs syndrome: a placebo-controlled crossover trial. Neurology. 2004;62:1405–1407. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120672.94060.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Allen R, Becker PM, Bogan R, et al. Ropinirole decreases periodic leg movements and improves sleep parameters in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:907–914. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: results from a 12-week, randomised, placebo-controlled study in 10 European countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Walters AS, Ondo WG, Dreykluft T, Grunstein R, Lee D, Sethi K. Ropinirole is effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. TREAT RLS 2: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1414–1423. doi: 10.1002/mds.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bliwise DL, Freeman A, Ingram CD, Rye DB, Chakravorty S, Watts RL. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, short-term trial of ropinirole in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bogan RK, Fry JM, Schmidt MH, Carson SW, Ritchie SY. Ropinirole in the treatment of patients with restless legs syndrome: a US-based randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:17–27. doi: 10.4065/81.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Montplaisir J, Nicolas A, Denesle R, Gomez-Mancilla B. Restless legs syndrome improved by pramipexole: a double-blind randomized trial. Neurology. 1999;52:938–943. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Partinen M, Hirvonen K, Jama L, et al. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole in idiopathic restless legs syndrome: a polysomnographic dose-finding study — the PRELUDE study. Sleep Med. 2006;7:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Winkelman JW, Sethi KD, Kushida CA, et al. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2006;67:1034–1039. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000231513.23919.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trenkwalder C, Stiasny-Kolster K, Kupsch A, Oertel WH, Koester J, Reess J. Controlled withdrawal of pramipexole after 6 months of open-label treatment in patients with restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1404–1410. doi: 10.1002/mds.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, Bergtholdt B, et al. Efficacy of pramipexole in restless legs syndrome: a six-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study (effect-RLS study) Mov Disord. 2007;22:213–219. doi: 10.1002/mds.21261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uitti RJ, Tanner CM, Rajput AH, Goetz CG, Klawans HL, Thiessen B. Hypersexuality with antiparkinsonian therapyClin Neuropharmacol. 1989;12:375–383. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Molina JA, Sáinz-Artiga MJ, Fraile A, et al. Pathologic gambling in Parkinson’s disease: a behavioral manifestation of pharmacologic treatment? Mov Disord. 2000;15:869–872. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<869::aid-mds1016>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tippmann-Peikert M, Park JG, Boeve BF, Shepard JW, Silber MH. Pathologic gambling in patients with restless legs syndrome treated with dopaminergic agonists. Neurology. 2007;68:301–303. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252368.25106.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rotigotine Sp 666 Study Group. Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Schollmayer E, Möller JC, Oertel WH. Patch application of the dopamine agonist rotigotine to patients with moderate to advanced stages of restless legs syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1432–1438. doi: 10.1002/mds.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rotigotine SP 709 Study Group. Oertel WH, Benes H, Garcia-Borreguero D, et al. Efficacy of rotigotine transdermal system in severe restless legs syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, six-week dose-finding trial in Europe. Sleep Med. 2008;9:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.SP790 Study Group. Trenkwalder C, Benes H, Poewe W, et al. Efficacy of rotigotine for treatment of moderate-to-severe restless legs syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:595–604. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.SP792 Study Group. Hening WA, Allen RP, Ondo WG, et al. Rotigotine improves restless legs syndrome: a 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in the United States. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1675–1683. doi: 10.1002/mds.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Högl B, Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, et al. Treatment of moderate to severe restless legs syndrome: 2-year safety and efficacy of rotigotine transdermal patch. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.SP710 study group. Oertel W, Trenkwalder C, Beneš H, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of rotigotine transdermal patch for moderate-to-severe idiopathic restless legs syndrome: a 5-year open-label extension study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:710–720. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Beneš H, García-Borreguero D, Ferini-Strambi L, Schollmayer E, Fichtner A, Kohnen R. Augmentation in the treatment of restless legs syndrome with transdermal rotigotine. Sleep Med 2012;xx:xx-xx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Earley CJ, Allen RP. Restless legs syndrome augmentation associated with tramadol. Sleep Med. 2006;7:592–593. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vetrugno R, Morgia C, D’Angelo R, et al. Augmentation of restless legs syndrome with long-term tramadol treatment. Mov Disord. 2007;22:424–427. doi: 10.1002/mds.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Garcia-Borreguero D, Allen RP, Kohnen R, Hogl B. Diagnostic standards for dopaminergic augmentation of restless legs syndrome: report from a World Association of Sleep Medicine – RLSSG consensus conference at the Max Planck Institute. Sleep Med. 2007;8:520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Silver N, Allen RP, Senerth J, Earley CJ. A 10-year, longitudinal assessment of dopamine agonists and methadone in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2011;12:440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Trenkwalder C, Högl B, Benes H, Kohnen R. Augmentation in restless legs syndrome is associated with low ferritin. Sleep Med. 2008;9:572–574. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, et al. The severity range of restless legs syndrome (RLS) and augmentation in a prospective patient cohort: association with ferritin levels. Sleep Med. 2009;10:611–615. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Management of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin (Neurontin) Sleep. 1996;19:224–246. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Adler CH. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:148–151. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Happe S, Klösch G, Saletu B. Zeitlhofer Treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome (RLS) with gabapentin. J Neurology. 2001;57:1717–1719. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, Llave Y, Verger K, Masramon X, Hernandez G. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin: a double-blind, cross-over study. Neurology. 2002;59:1573–1579. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.10.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Happe S, Sauter C, Klösch G, Saletu B, Zeitlhofer J. Gabapentin versus ropinirole in the treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neuropsychobiology. 2003;48:82–86. doi: 10.1159/000072882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Saletu M, Anderer P, Saletu-Zyhlarz GM, et al. Comparative placebo-controlled polysomnographic and psychometric studies on the acute effects of gabapentin versus ropinirole in restless legs syndrome. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:463–473. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Thorp ML, Morris CD, Bagby SP. A crossover study of gabapentin in treatment of restless legs syndrome among hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:104–108. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.25202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Micozkadioglu H, Ozdemir FN, Kut A, Sezer S, Saatci U, Haberal M. Gabapentin versus levodopa for the treatment of Restless legs syndrome in hemodialysis patients: an open-label study. Ren Fail. 2004;26:393–397. doi: 10.1081/jdi-120039823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Merlino G, Serafini A, Lorenzut S, Sommaro M, Gigli GL, Valente M. Gabapentin enacarbil in restless legs syndrome. Drugs Today (Barc) 2010;46:3–11. doi: 10.1358/dot.2010.46.1.1424766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.XP052 Study Group. Kushida CA, Becker PM, Ellenbogen AL, Canafax DM, Barrett RW. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of XP13512/GSK1838262 in patients with RLS. Neurology. 2009;72:439–446. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341770.91926.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Walters AS, Ondo WG, Kushida CA, XP045 Study Group et al. Gabapentin enacarbil in restless legs syndrome: a phase 2b, 2-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32:311–320. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181b3ab16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kushida CA, Walters AS, Becker P, XP021 Study Group et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of XP13512/GSK1838262 in the treatment of patients with primary restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2009;32:159–168. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bogan RK, Bornemann MA, Kushida CA, Trân PV, Barrett RW, XP060 Study Group Long-term maintenance treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin enacarbil: a randomized controlled study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:512–521. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ellenbogen AL, Thein SG, Winslow DH, et al. A 52-week study of gabapentin enacarbil in restless legs syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:8–16. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3182087d48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]