Abstract

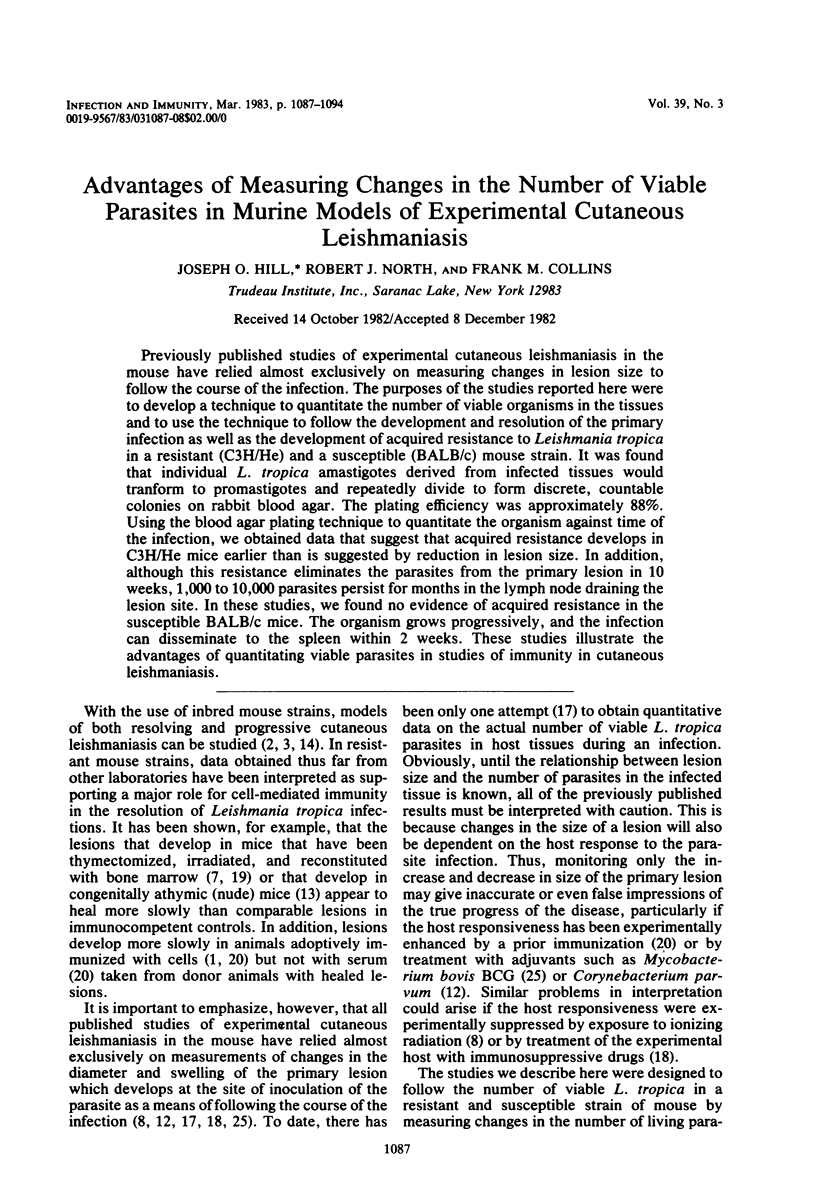

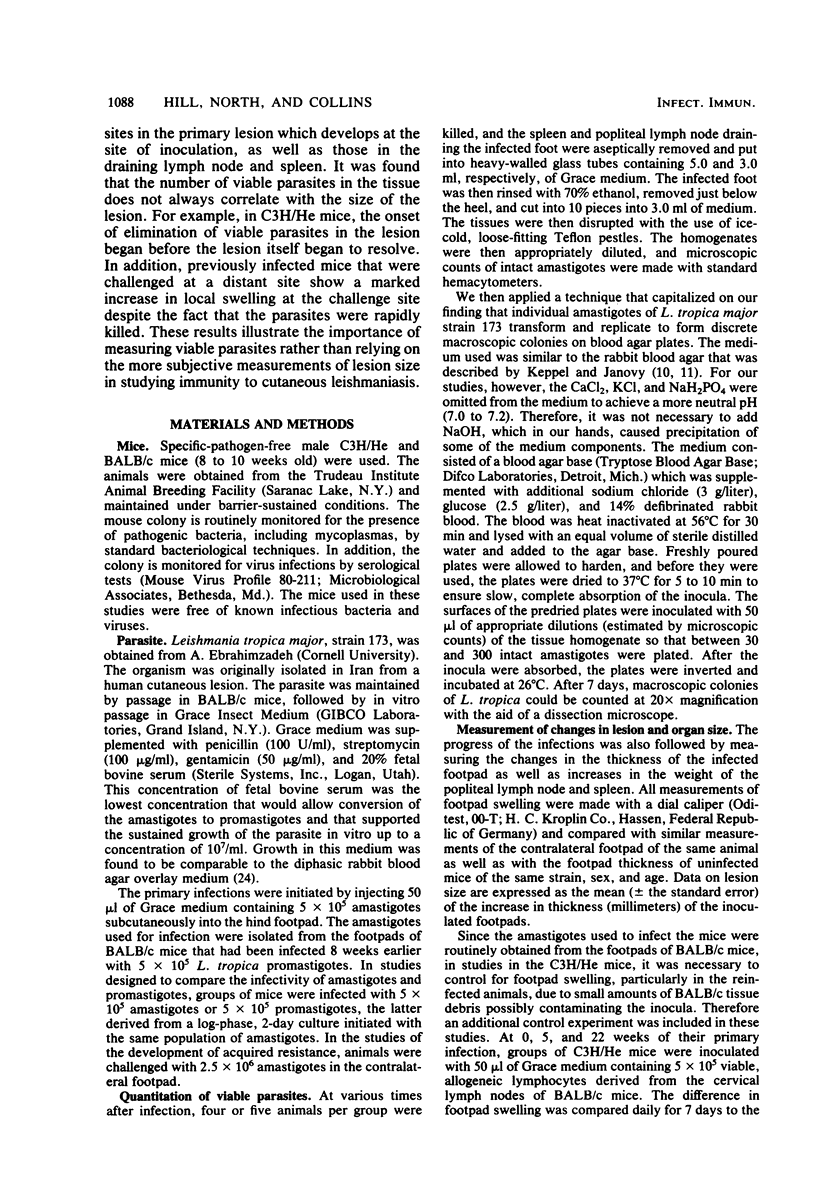

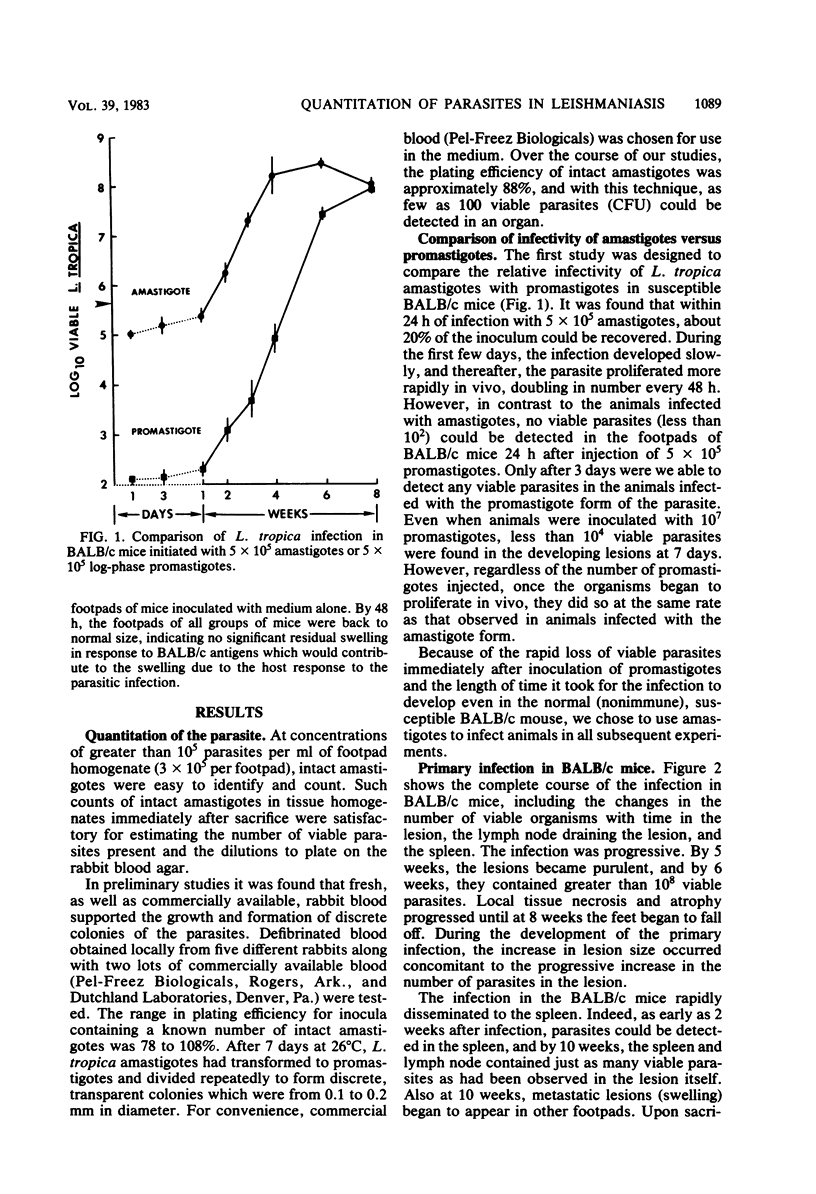

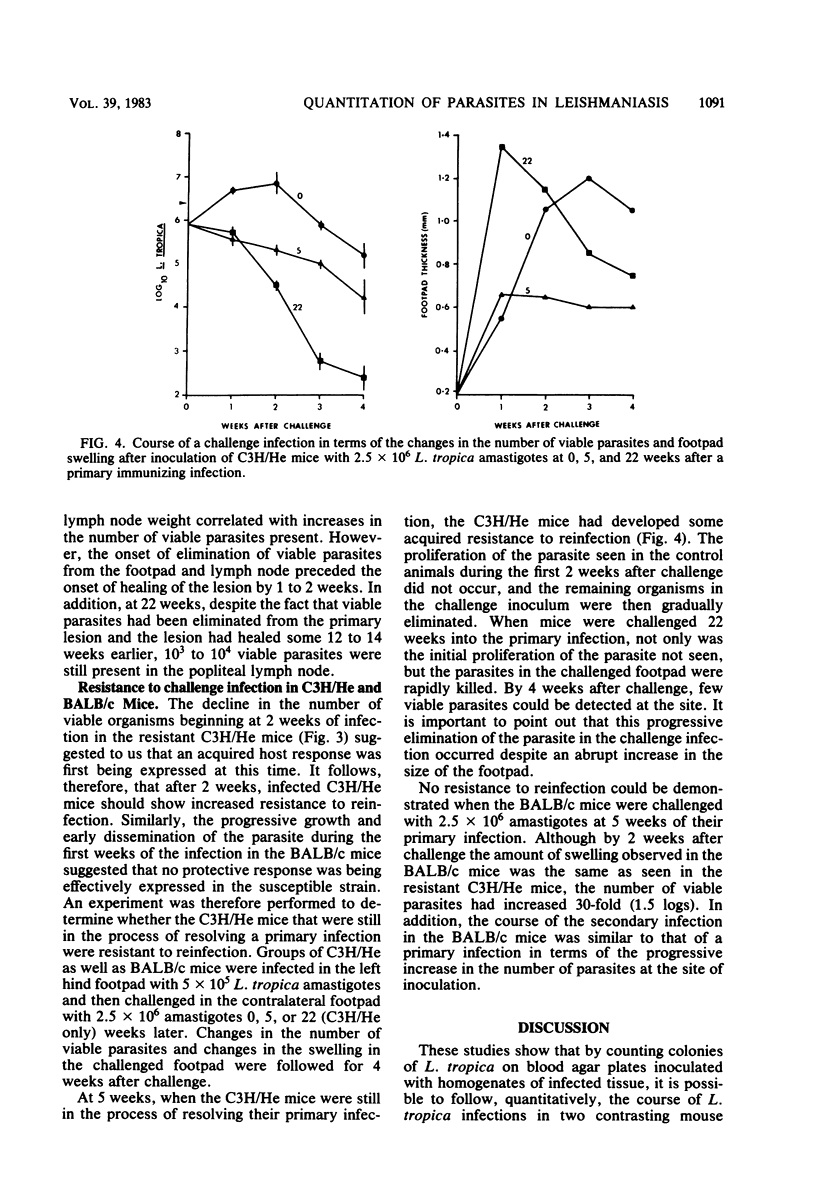

Previously published studies of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis in the mouse have relied almost exclusively on measuring changes in lesion size to follow the course of the infection. The purposes of the studies reported here were to develop a technique to quantitate the number of viable organisms in the tissues and to use the technique to follow the development and resolution of the primary infection as well as the development of acquired resistance to Leishmania tropica in a resistant (C3H/He) and a susceptible (BALB/c) mouse strain. It was found that individual L. tropica amastigotes derived from infected tissues would transform to promastigotes and repeatedly divide to form discrete, countable colonies on rabbit blood agar. The plating efficiency was approximately 88%. Using the blood agar plating technique to quantitate the organism against time of the infection, we obtained data that suggest that acquired resistance develops in C3H/He mice earlier than is suggested by reduction in lesion size. In addition, although this resistance eliminates the parasites from the primary lesion in 10 weeks, 1,000 to 10,000 parasites persist for months in the lymph node draining the lesion site. In these studies, we found no evidence of acquired resistance in the susceptible BALB/c mice. The organism grows progressively, and the infection can disseminate to the spleen within 2 weeks. These studies illustrate the advantages of quantitating viable parasites in studies of immunity in cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander J., Phillips R. S. Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania tropica major: adoptive transfer of immunity in mice. Exp Parasitol. 1980 Feb;49(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(80)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behin R., Mauel J., Sordat B. Leishmania tropica: pathogenicity and in vitro macrophage function in strains of inbred mice. Exp Parasitol. 1979 Aug;48(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(79)90057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorvatn B., Neva F. A. A model in mice for experimental leishmaniasis with a West African strain of Leishmania tropica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979 May;28(3):472–479. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray R. S., Munford F. On the maintenance of strains of Leishmania from the Guianas. J Trop Med Hyg. 1967 Jan;70(1):23–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handman E., Ceredig R., Mitchell G. F. Murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: disease patterns in intact and nude mice of various genotypes and examination of some differences between normal and infected macrophages. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1979 Feb;57(1):9–29. doi: 10.1038/icb.1979.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson V. H., Herman R., Semprevivo L. Leishmania donovani: correlation among assays of amastigote viability. Exp Parasitol. 1980 Dec;50(3):397–408. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(80)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. G., Hale C., Liew F. Y. Immunological regulation of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. III. Nature and significance of specific suppression of cell-mediated immunity in mice highly susceptible to Leishmania tropica. J Exp Med. 1980 Sep 1;152(3):594–607. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.3.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. G., Hale C., Liew F. Y. Immunological regulation of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. IV. Prophylactic effect of sublethal irradiation as a result of abrogation of suppressor T cell generation in mice genetically susceptible to Leishmania tropica. J Exp Med. 1981 Mar 1;153(3):557–568. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithly J. S. Infectivity of Leishmania donovani amastigotes and promastigotes for golden hamsters. J Protozool. 1976 May;23(2):244–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1976.tb03763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel A. D., Janovy J., Jr Herpetomonas megaseliae and Crithidia harmosa: growth on blood-agar plates. J Parasitol. 1977 Oct;63(5):879–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel A. D., Janovy J., Jr Morphology of Leishmania donovani colonies grown on blood agar plates. J Parasitol. 1980 Oct;66(5):849–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell G. F., Curtis J. M., Handman E. Resistance to cutaneous leishmaniasis in genetically susceptible BALB/c mice. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1981 Oct;59(Pt 5):555–565. doi: 10.1038/icb.1981.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell G. F., Curtis J. M., Scollay R. G., Handman E. Resistance and abrogation of resistance to cutaneous leishmaniasis in reconstituted BALB/c nude mice. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1981 Oct;59(Pt 5):539–554. doi: 10.1038/icb.1981.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter L. W., Pandolph C. R. Mechanisms of immunity to leishmaniasis. IV. Significance of lymphatic drainage from the site of infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982 May;48(2):396–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter L. W. The quantification of viable Leishmania enriettii from infected guinea-pig tissues. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979 Apr;36(1):24–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston P. M., Behbehani K., Dumonde D. C. Experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis: VI: anergy and allergy in the cellular immune response during non-healing infection in different strains of mice. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1978 Nov;1(3):207–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston P. M., Carter R. L., Leuchars E., Davies A. J., Dumonde D. C. Experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. 3. Effects of thymectomy on the course of infection of CBA mice with Leishmania tropica. Clin Exp Immunol. 1972 Feb;10(2):337–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston P. M., Dumonde D. C. Experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. V. Protective immunity in subclinical and self-healing infection in the mouse. Clin Exp Immunol. 1976 Jan;23(1):126–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez H., Arredondo B., Machado R. Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania tropica: cross immunity in C57BL/6 mice. Exp Parasitol. 1979 Aug;48(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(79)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P. A., Farrell J. P. Experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. I. Nonspecific immunodepression in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania tropica. J Immunol. 1981 Dec;127(6):2395–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauber L. A. The origin and significance of the distribution of parasites in visceral leishmaniasis. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1966 Mar;28(5):635–643. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1966.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOBIE E. J., VON BRAND T., MEHLMAN B. Cultural and physiological observations on Trypanosoma rhodesiense and Trypanosoma gambiense. J Parasitol. 1950 Feb;36(1):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub J., Weinbaum F. I. The effect of BCG on experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis in mice. J Immunol. 1977 Jun;118(6):2288–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]