Abstract

Recent several studies have shown that the genetic variation of SCN5A is related with atrioventricular conduction block (AVB); no study has yet been published in Koreans. Therefore, to determine the AVB-associated genetic variation in Korean patients, we investigated the genetic variation of SCN5A in Korean patients with AVB and compared with normal control subjects. We enrolled 113 patients with AVB and 80 normal controls with no cardiac symptoms. DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood, and all exons (exon 2-exon 28) except the untranslated region and exon-intron boundaries of the SCN5A gene were amplified by multiplex PCR and directly sequenced using an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer. When a variation was discovered in genomic DNA from AVB patients, we confirmed whether the same variation existed in the control genomic DNA. In the present study, a total of 7 genetic variations were detected in 113 AVB patients. Of the 7 variations, 5 (G87A-A29A, intervening sequence 9-3C>A, A1673G-H558R, G3578A-R1193Q, and T5457C-D1819D) have been reported in previous studies, and 2 (C48G-F16L and G3048A-T1016T) were novel variations that have not been reported. The 2 newly discovered variations were not found in the 80 normal controls. In addition, G298S, G514C, P1008S, G1406R, and D1595N, identified in other ethnic populations, were not detected in this study. We found 2 novel genetic variations in the SCN5A gene in Korean patients with AVB. However, further functional study might be needed.

Keywords: atrioventricular block, Korean, multiplex polymerase chain reaction, sodium channel protein type 5 subunit alpha

Introduction

The SCN5A gene, encoding a voltage-gated Na+ channel, is predominately expressed in the heart, where it has a key role in the generation and propagation of the cardiac impulse [1].

Voltage-gated Na+ channels are transmembrane proteins that produce the fast inward Na+ current responsible for the depolarization phase of the cardiac action potential. Inherited variations in SCN5A, the gene encoding the pore-forming α-subunit of the cardiac-type Na+ channel (Nav1.5), result in a spectrum of disease entities, termed Na+ channelopathies.

In many previous studies, lots of variations of the SCN5A gene have been observed in various cardiac diseases, such as long-QT syndrome (LQT), Brugada syndrome (Brs), progressive cardiac conduction defect, atrial fibrillation (AF), dilated cardiomyopathy, and overlapping syndromes [2, 3].

Recently, cardiac conduction system disease, manifesting as slower intramyocardial conduction and, in some cases, atrioventricular conduction block (AVB), has been related to SCN5A mutation [4]. Familial AVB, characterized by progressive "degree of block" in association with variable apparent "site of block," may be transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. Two genetically distinct forms of AVB have been identified [5]. Brink et al. [6] established a genetic link between AVB and a genetic locus at chromosome 19q13, and Schott et al. [4] mapped AVB to chromosome 3p21.

Such genetic variations in AVB patients have been widely studied in Caucasians, Han Chinese, and Japanese, but no study has yet been published in Koreans as far we know. Therefore, we carried out a complete sequencing of coding regions of the SCN5A gene, except the untranslated region, in Korean AVB patients to investigate the SCN5A variations associated with AVB and compared them with normal control subjects. This is the first study of SCN5A genetic variations that examined all coding regions in Korean patients with AVB.

Methods

Patient enrollment

We enrolled 113 Korean AVB patients who were diagnosed with electrocardiograms and who had inserted permanent pacemakers and 80 normal controls with no cardiac symptoms. All patients and control subjects were recruited from four medical centers - Keimyung University, Yeungnam University, Catholic University, and Fatima Hospital (Daegu, Korea) - from August 2009 to September 2011.

This study was approved by the ethical committee at each hospital; consent was obtained from all individuals before enrollment into the study.

DNA extraction

In this study, peripheral blood was collected into ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid-containing tubes, and genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from whole blood samples using the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Hilden, Germany). DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA), and purity of the DNA was assessed based on the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio.

Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequence analysis

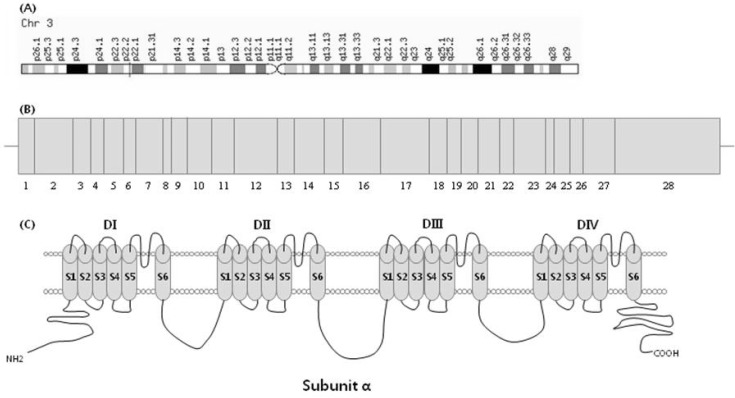

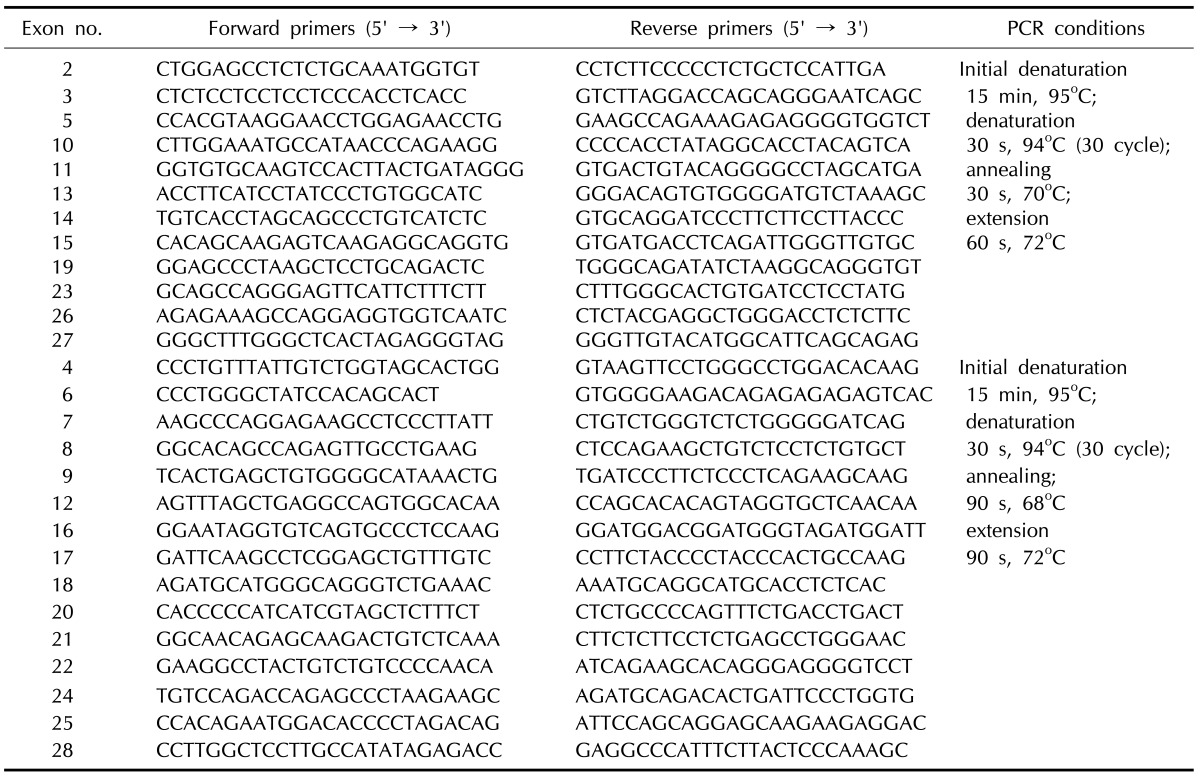

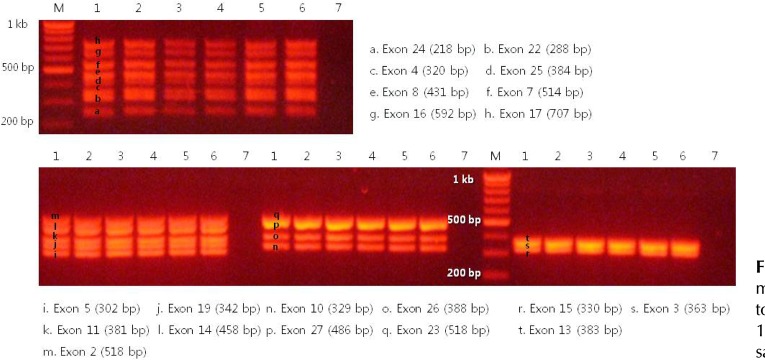

The SCN5A gene is located on human chromosome 3p21, and the gene consists of 28 exons (Fig. 1) and encodes a protein of 2,016 amino acids with a molecular mass of 227 kDa [7]. Entire coding regions, including exon-intron boundaries of the SCN5A gene, were amplified by multiplex PCR-based direct sequencing. The primers for PCR amplification were designed based on the GenBank reference sequence; primers are shown in Table 1. PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 95℃ for 15 min; and denaturation at 94℃ for 30 s, annealing at 68-70℃ for 30-60 s, and extension at 72℃ for 60-90 s, repeated for 30 cycles (Table 1). After multiplex PCR, the reaction mixture was electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide (Fig. 2). Then, amplified PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and directly sequenced using the BigDye Terminator ver 3.1 cycle sequencing kit on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Fig. 1.

Genomic location and exon image of SCN5A gene and voltage-gated Na+ channel α subunit. (A) The SCN5A gene is located on human chromosome 3p21. (B) Structure of SCN5A gene: the SCN5A gene consists of 28 exons; among these, exon 1 is an untranslated region. (C) The voltage-gated Na+ channel α subunit consists of 4 homologous domains (DI-DIV), each containing 6 transmembrane-spanning segments (S1-S6).

Table 1.

Multiplex PCR primers for amplification of the coding regions and flanking intronic sites of SCN5A and PCR conditions for each primer pair

Fig. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of multiplex PCR products from exon 2 to exon 28 of the SCN5A gene. M, 100 bp DNA size marker; lane 1-6, sample 1-6; lane 7, negative control.

Sequencing results were compared with the reference sequences (SCN5A/NM_198056.2/ENSG00000183873/ENST00000333535) using the alignment program BLAST 2.0 of NCBI, and we determined the portion of variation that occurred. When a variation was discovered in genomic DNA from patients, we confirmed whether the same variation existed in the control genomic DNA.

Statistical analysis

p-values and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each genotype and allele were evaluated by χ2 analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference between AVB patients and normal controls of the study.

Results

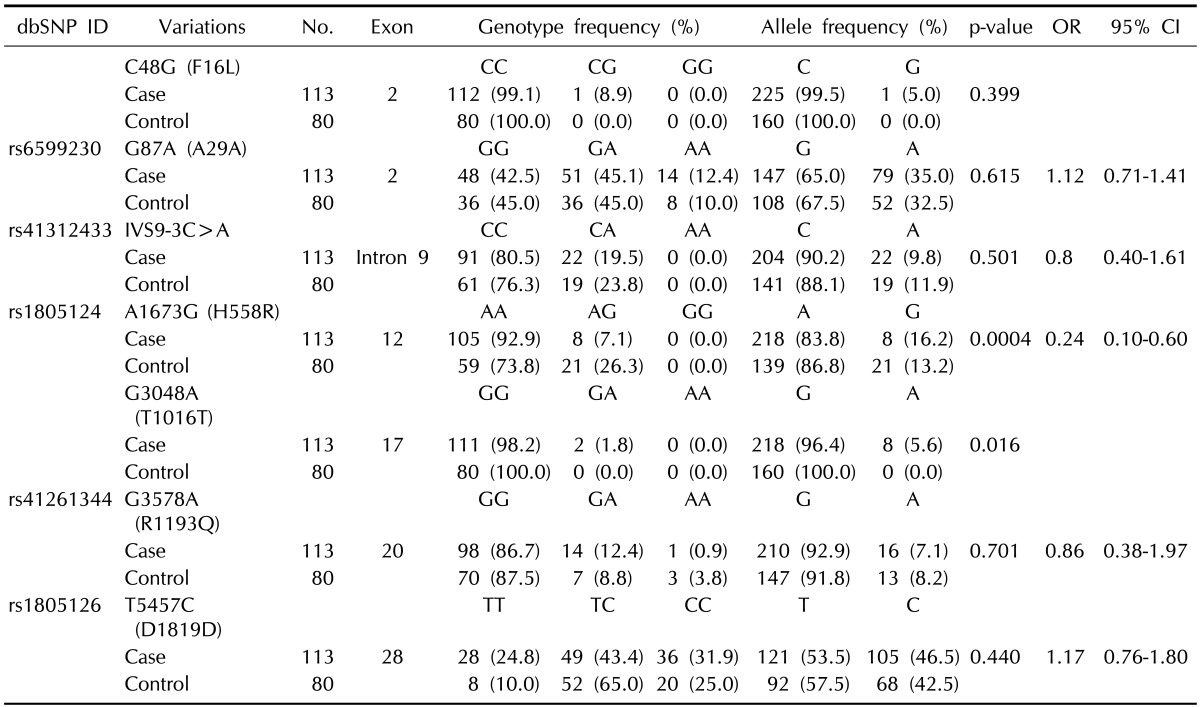

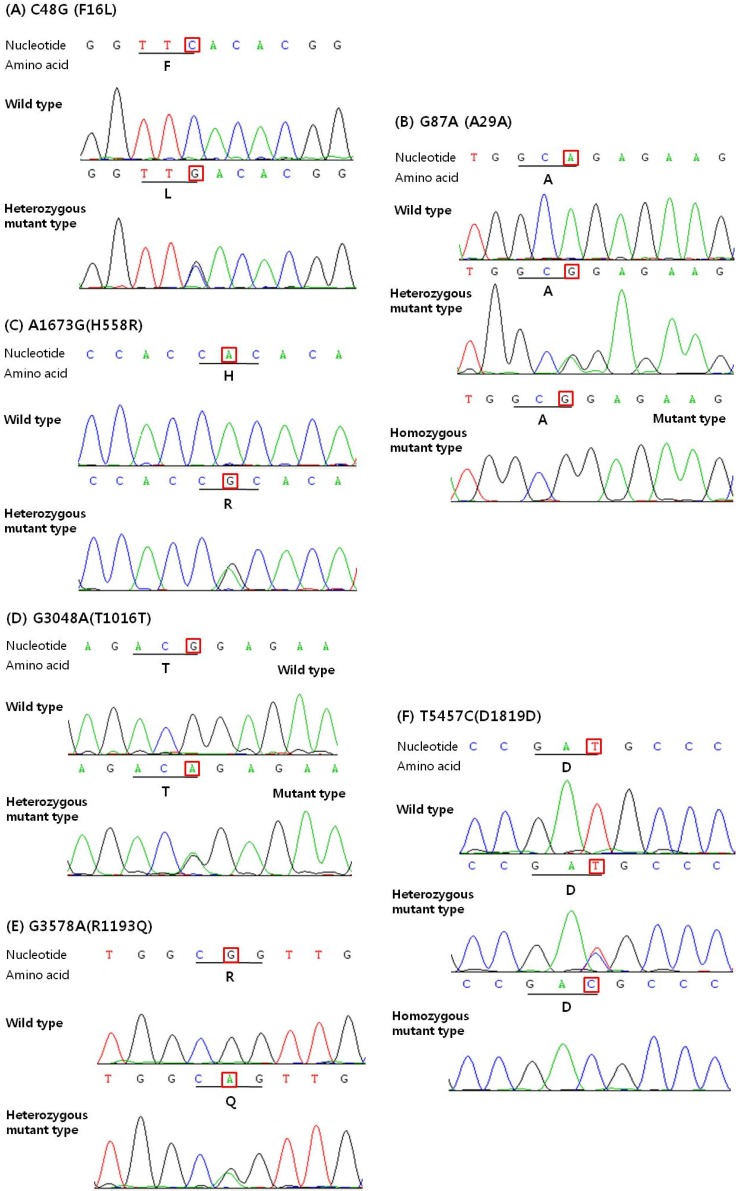

In the present study, we sequenced all translated exons and exon-intron boundaries of the SCN5A gene from 113 Korean AVB patients. As a result, we identified 7 genetic variations (of these, 5 were known variations and 2 were novel variations), consisting of 3 synonymous (G87A-A29A, G3048A-T1016T, and T5457C-D1819D), 3 non-synonymous (C48G-F16L, A1673G-H558R, and G3578A-R1193Q), and 1 splicing donor site of the intron 9-exon 10 boundary (intervening sequence [IVS] 9-3C > A) (Table 2). The examples of the sequencing result are shown in Fig. 3. Among the 7 genetic variations, 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been reported by American and Japanese researchers: non-synonymous SNP in exon 12 (rs1805124, A1673G-H558R) and synonymous SNP in exon 28 (rs1805126, C5457T-D1819D). A1673G-H558R was identified in 18% of the American populations (n = 71) and 8% of the Japanese populations (n = 100) [8, 9], and C5457T-D1819D was observed in 12.3% of the American populations (n = 130) and 46% of the Japanese populations (n = 100) [9, 10]. We also discovered a synonymous SNP (rs6599230: G87A-A29A, in exon 2) and non-synonymous SNP (rs41261344, G3578A-R1193Q, in exon 20) that are very common polymorphisms in the Han Chinese population. In addition, we identified 2 novel variations that have not been previously reported. One of these variations was heterozygous synonymous (G3048A-T1016T), and the other was heterozygous non-synonymous (C48G-F16L). The genotype and allele frequencies of the identified genetic variations are summarized in Table 2. There were significant differences in the allele frequencies of A1673G-H558R and G3048A (T1016T) between the two groups (p < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in allele frequencies of the other genetic variations between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Genetic variations and allele frequencies in the SCN5A gene of Korean complete atrioventricular conduction block patients (n=113) and normal controls (n=80)

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Results of DNA sequencing analysis of SCN5A gene, showing nucleotide and amino acid changes. DNA sequencing results of SCN5A exon 2 (A, B), exon 12 (C), exon 17 (D), exon 20 (E), and exon 28 (F). C48G-F16L (A), A1673G-H558R (C), G3048A-T1016T (D), and G3578A-R1193Q (E) are all heterozygous nucleotide changes. G87A-A29A (B) and T5457C-D1819D (F) are heterozygous or homozygous changes that are causing the synonymous nucleotide change.

However, G298S [11], G514C [12], P1008S [13], G1406R [14], and D1595N [11], identified in other ethnic populations, were not detected, and A3075T-E1025D and T4847A-F1616Y, discovered in 105 Korean sick sinus syndrome patients in our previous study, were also not detected in this study.

Next, to compare with normal controls, we analyzed normal samples by the same methods whether the same variations existed in their genes. Just as in the patient group, 4 SNPs (rs6599230, G87A-A29A; rs41312434, IVS9-3C > A; rs1805124, A1673G-H558R; rs1805126, C5457T-D1819D) were detected in the normal control group, but 1 non-synonymous SNP (rs41261344, G3578A-R1193Q) and 2 novel variations (C48G-F16L and G3048A-T1016T) were not detected in the normal control group.

Discussion

This is the first case report with genetic variations of SCN5A in Korean patients with AVB. To date, a number of SCN5A variations associated with various cardiac diseases, such as LQT, Brs, progressive cardiac conduction defect, AF, and overlapping syndromes, have been reported. Although SCN5A genetic variations associated with AVB have been well studied in Caucasians, Han Chinese, and Japanese, no study has yet been published in Koreans as far we know. In previous studies, it has been shown that in some cases, progressive AVB has been linked to SCN5A gene variations [4]. Furthermore, in our prior study, 2 novel variations were detected in Korean sick sinus syndrome (SSS) patients, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported in any ethnic group.

The variations could be significantly associated with functional effects of the SCN5A gene. Based on these results, we searched for SCN5A genetic variations in Korean AVB and compared them with those of control subjects. The SCN5A gene consists of 28 exons and encodes a protein of 2016 amino acids with a molecular mass of 227 kDa [7]. In our patients with AVB, there were 7 sites of nucleotide change from exon 2 to exon 28 of the SCN5A gene. Among of them, 2 sites (G87A-A29A, IVS9-3C > A) were reported as genetic variations in a Western study [7], and T5457C-D1819D has already been reported as a variation or polymorphism without functional effects on the channel in Asian studies [7, 15, 16]. A1673G-H558R is located in the Na+ channel I, II interdomain linker, and previous functional studies have shown that the H558R-encoding minor allele can alter the phenotype of true disease-causing SCN5A mutations [17]. It has been suggested that it modulates Na+ channel functional changes caused by other variations and plays a role in intragenic complementation [18, 19]. Previously, the H558R G allele has been associated with occurrence of early-onset AF and LQT interval in healthy populations. The H558R G allele frequency has been reported to be 20.4-32% in the white population, 29% in the black population, and 10.4% in the Chinese population. In our study, the G allele frequency of SCN5A mutation carriers was 8% and 13.1% in the normal control group.

G3578A-R1193Q, which can cause a gain of the sodium ion channel function and cause LQT3 and Brs, was also found. It has been reported that G3578A-R1193Q confers a risk of LQT3 or Brs in the general population, although it seems to be a common polymorphism in the Han Chinese population. Electrophysiological studies showed that R1193Q destabilizes inactivation gating and generates a persistent, non-inactivating current, which results in a gain of the sodium channel function, as in LQT3 syndrome [20, 21].

In addition to previously reported variations, we identified 2 novel variations that were not reported in the case of Japanese and Chinese populations. One of these variations was heterozygous non-synonymous (C48G-F16L), and the other was heterozygous synonymous (G3048A-T1016T). Since a non-synonymous nucleotide change in the SCN5A gene is likely to induce a functional change in the sodium channel, a non-synonymous substitution was considered a candidate for the variation associated with this disorder. In this study, a non-synonymous variation, C48G-F16L, was not found in the normal control group but was detected only in the patient group, suggesting that it may effect AVB. However, G298S [11], G514C [12], P1008S [13], G1406R [14], and D1595N [11], identified in other ethnic populations, were not detected, thought to be due to very low frequency or no variation in the Korean population.

In summary, our data may provide useful information for the identification of novel variations related to AVB, and the novel variants may provide useful bio-markers to study Korean cardiac disease.

In a future study, we will conduct a functional analysis of the novel variation (C48G-F16L) and propose a mechanism for its contribution to the AVB phenotype in patients. Also, we will try to find out genetic variation sites in other genes that might be responsible for AVB.

References

- 1.Grant AO. Molecular biology of sodium channels and their role in cardiac arrhythmias. Am J Med. 2001;110:296–305. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00714-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin CH, Kim NH, Kim KH, Yoo SS, Choi YB, Oh SK, et al. A family with a missense mutation in the SCN5A gene. Korean Circ J. 2003;33:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan HL, Bezzina CR, Smits JP, Verkerk AO, Wilde AA. Genetic control of sodium channel function. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:961–973. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schott JJ, Alshinawi C, Kyndt F, Probst V, Hoorntje TM, Hulsbeek M, et al. Cardiac conduction defects associate with mutations in SCN5A. Nat Genet. 1999;23:20–21. doi: 10.1038/12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKusick-Nathans Institute for Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Bethesda, MD: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM; [Accessed 2001 Dec 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brink PA, Ferreira A, Moolman JC, Weymar HW, van der Merwe PL, Corfield VA. Gene for progressive familial heart block type I maps to chromosome 19q13. Circulation. 1995;91:1633–1640. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gellens ME, George AL, Jr, Chen LQ, Chahine M, Horn R, Barchi RL, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of the human cardiac tetrodotoxin-insensitive voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:554–558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang P, Kanki H, Drolet B, Yang T, Wei J, Viswanathan PC, et al. Allelic variants in long-QT disease genes in patients with drug-associated torsades de pointes. Circulation. 2002;105:1943–1948. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014448.19052.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasa H, Itoh T, Nagai R, Nakamura Y, Tanaka T. Twenty single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and their allelic frequencies in four genes that are responsible for familial long QT syndrome in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2000;45:182–183. doi: 10.1007/s100380050207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wattanasirichaigoon D, Vesely MR, Duggal P, Levine JC, Blume ED, Wolff GS, et al. Sodium channel abnormalities are infrequent in patients with long QT syndrome: identification of two novel SCN5A mutations. Am J Med Genet. 1999;86:470–476. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991029)86:5<470::aid-ajmg13>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang DW, Viswanathan PC, Balser JR, George AL, Jr, Benson DW. Clinical, genetic, and biophysical characterization of SCN5A mutations associated with atrioventricular conduction block. Circulation. 2002;105:341–346. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan HL, Bink-Boelkens MT, Bezzina CR, Viswanathan PC, Beaufort-Krol GC, van Tintelen PJ, et al. A sodium-channel mutation causes isolated cardiac conduction disease. Nature. 2001;409:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/35059090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Nesterenko VV, Pfeiffer R, Guerchicoff A, Cordeiro JM, et al. Dual variation in SCN5A and CACNB2b underlies the development of cardiac conduction disease without Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyndt F, Probst V, Potet F, Demolombe S, Chevallier JC, Baro I, et al. Novel SCN5A mutation leading either to isolated cardiac conduction defect or Brugada syndrome in a large French family. Circulation. 2001;104:3081–3086. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.100834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JZ, Xie XD, Wang XX, Tao M, Shang YP, Guo XG. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the SCN5A gene in Han Chinese and their relation with Brugada syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117:652–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin DJ, Jang Y, Park HY, Lee JE, Yang K, Kim E, et al. Genetic analysis of the cardiac sodium channel gene SCN5A in Koreans with Brugada syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:573–578. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahata T, Yasui-Furukori N, Sasaki S, Igarashi T, Okumura K, Munakata A, et al. Nucleotide changes in the translated region of SCN5A from Japanese patients with Brugada syndrome and control subjects. Life Sci. 2003;72:2391–2399. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye B, Valdivia CR, Ackerman MJ, Makielski JC. A common human SCN5A polymorphism modifies expression of an arrhythmia causing mutation. Physiol Genomics. 2003;12:187–193. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00117.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viswanathan PC, Benson DW, Balser JR. A common SCN5A polymorphism modulates the biophysical effects of an SCN5A mutation. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:341–346. doi: 10.1172/JCI16879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun A, Xu L, Wang S, Wang K, Huang W, Wang Y, et al. SCN5A R1193Q polymorphism associated with progressive cardiac conduction defects and long QT syndrome in a Chinese family. J Med Genet. 2008;45:127–128. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.056333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang HW, Chen JJ, Lin YJ, Shieh RC, Lee MT, Hung SI, et al. R1193Q of SCN5A, a Brugada and long QT mutation, is a common polymorphism in Han Chinese. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e7. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]