Abstract

A sample size with sufficient statistical power is critical to the success of genetic association studies to detect causal genes of human complex diseases. Genome-wide association studies require much larger sample sizes to achieve an adequate statistical power. We estimated the statistical power with increasing numbers of markers analyzed and compared the sample sizes that were required in case-control studies and case-parent studies. We computed the effective sample size and statistical power using Genetic Power Calculator. An analysis using a larger number of markers requires a larger sample size. Testing a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) marker requires 248 cases, while testing 500,000 SNPs and 1 million markers requires 1,206 cases and 1,255 cases, respectively, under the assumption of an odds ratio of 2, 5% disease prevalence, 5% minor allele frequency, complete linkage disequilibrium (LD), 1:1 case/control ratio, and a 5% error rate in an allelic test. Under a dominant model, a smaller sample size is required to achieve 80% power than other genetic models. We found that a much lower sample size was required with a strong effect size, common SNP, and increased LD. In addition, studying a common disease in a case-control study of a 1:4 case-control ratio is one way to achieve higher statistical power. We also found that case-parent studies require more samples than case-control studies. Although we have not covered all plausible cases in study design, the estimates of sample size and statistical power computed under various assumptions in this study may be useful to determine the sample size in designing a population-based genetic association study.

Keywords: case-control studies, case-parent study, genetic association studies, sample size, statistical power

Introduction

In genetic epidemiological research, both case-control and case-parent trio designs have been used widely to evaluate genetic susceptibilities to human complex diseases and markers, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), to localize disease gene variants [1-5]. The sample size for detecting associations between disease and SNP markers is known to be highly affected by disease prevalence, disease allele frequency, linkage disequilibrium (LD), inheritance models (e.g., additive, dominant, and multiplicative models), and effect size of the genetic variants (e.g., odds ratio, relative risk, etc.) [4, 6, 7]. Previous studies have shown that a population based case-control design can be more powerful than a family-based study design in identifying genes predisposing human complex traits, both for qualitative traits and for quantitative traits [8-11]. However, some studies reported that the case-parent design is much more powerful than the case-control design in evaluating genetic risk for common complex diseases, because case-control studies are susceptible to bias due to phenotype misclassification or population stratification [12, 13].

Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) using thousands of cases and controls reported many susceptibility SNPs for 237 human traits by the end of June, 2011 (www.genome.gov/GWAStudies). Since a GWAS evaluates hundreds of thousands of SNP markers, it requires a much larger sample size to achieve an adequate statistical power [14-18]. In genetic association studies, the observed signal for association is referred to be statistically significant if the p-value is less than a preset threshold value (α) of 0.05 to reject a null hypothesis of genetic association. Testing a large number of SNP markers leads to a large number of multiple comparisons and thus increases false positive rates. Either the Bonferroni correction or the false discovery rate is generally applied to avoid false positive (type I error) rates. However, the Bonferroni-corrected p-value, the significance threshold set to 0.05 divided by the total number of SNPs analyzed in a GWAS, is too strict to consider the correlations among SNP markers (e.g., p = 1 × 10-7 for 500,000 (500 K) SNPs, p = 5 × 10-8 for 1 million (M) SNPs) [16, 19]. Therefore, estimating a sufficient sample size to achieve adequate statistical power is critical in the design stage of genetic association [20-24].

Statistical power is the probability to reject a null hypothesis (H0) while the alternative hypothesis (HA) is true. It is affected by many factors. For instance, a larger sample size is required to achieve sufficient statistical power. Although a researcher collects a large number of samples, all samples may not be necessary to be analyzed to detect evidence for association. A large sample size improves the ability of disease prediction; however, it is not cost-effective that a researcher genotypes more than the effective sample size [25]. Unless researchers estimate sample size and statistical power at the research design stage, it leads to wasted time and resources to collect samples. An effective sample size can be defined as the minimum number of samples that achieves adequate statistical power (e.g., 80% power). On the other hand, too small a sample size to detect true evidence for an association increases false negative rates and reduces the reliability of a study. False negative rates are increased by multiple factors that cause systematic biases, and such biases reduce statistical power [26]. The statistical power of 80% is used widely to avoid false negative associations and to determine a cost-effective sample size in large-scale association studies [7, 22, 23]. However, many researchers tend to overlook the importance of statistical power and sample size calculations.

In this study, we evaluated statistical power with increasing numbers of markers analyzed under various assumptions and compared the sample sizes required in case-control studies and case-parent studies.

Methods

We computed the effective sample size and statistical power using a web browser program, Genetic Power Calculator developed by Purcell et al. [27] (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/gpc/), for both case-control and case-parent studies. We conducted power and sample size calculations under various assumptions about genetic models (i.e., allelic, additive, dominant, recessive, and co-dominant models), minor allele frequencies (MAFs), pair-wise LD, disease prevalence, case-to-control ratio, and number of SNP markers (i.e., single SNP, 500 K SNPs, and 1 M SNPs). The values tested for heterozygous odds ratio (ORhet) were 1.3, 1.5, 2, and 2.5. The power and sample sizes were calculated under different ranges of factors, such as MAF of 5%, 10%, 20%, and 30%; LD of 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1; disease prevalence of 0.01%, 0.1%, 5%, and 10%; and case-to-control ratio of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4. We assumed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium at the disease-susceptible allele.

The Bonferroni p-value that was specific to the number of SNP makers tested was applied to cover 3 billion base pairs of the human genome (i.e., p = 0.05 for a single SNP marker, p = 1 × 10-7 for 500 K SNP markers, and p = 5 × 10-8 for 1 M SNP markers). We fixed the proper range of sample sizes from 100 to 2,000 cases, because the power is too low when the sample size is below 100 cases (or trios), and the cost is too high to realistically collect samples when the sample size is above 2,000 [7, 22].

Results

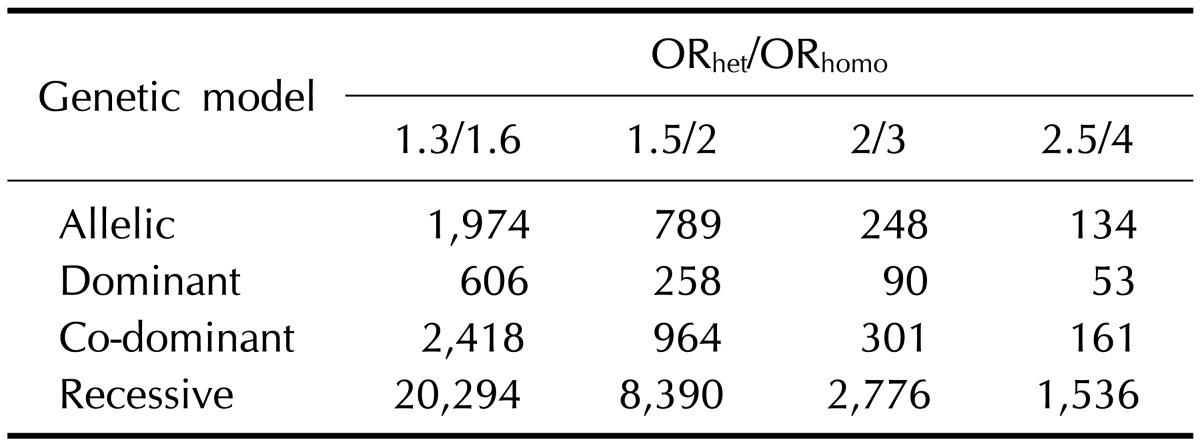

We calculated the sample size to achieve 80% statistical power according to the genetic models and the heterozygous ORs using a single SNP marker in a case-control study under the assumptions of 5% disease prevalence, 5% MAF, complete LD, 1:1 case-to-control ratio, and 5% type I error rate (α) (Table 1). The dominant model required the smallest sample size to achieve 80% power compared to other genetic models (e.g., 90 cases). In contrast, the effective sample size to test a single SNP under the recessive model was too large to collect with a limited budget, even if the homozygous OR is greater than 4 (e.g., 1,536 cases). It reveals difficulty in detecting a disease allele that follows a recessive mode of inheritance with a moderate sample size.

Table 1.

Number of cases required to achieve 80% power according to the different genetic models in a case-control study

Assumptions: 5% minor allele frequency, 5% disease prevalence, complete linkage disequilibrium (D'=1), 1:1 case-control ratio, and 5% type I error rates for single marker analyses.

ORhet/ORhomo, odds ratios of heterozygotes/rare homozygotes.

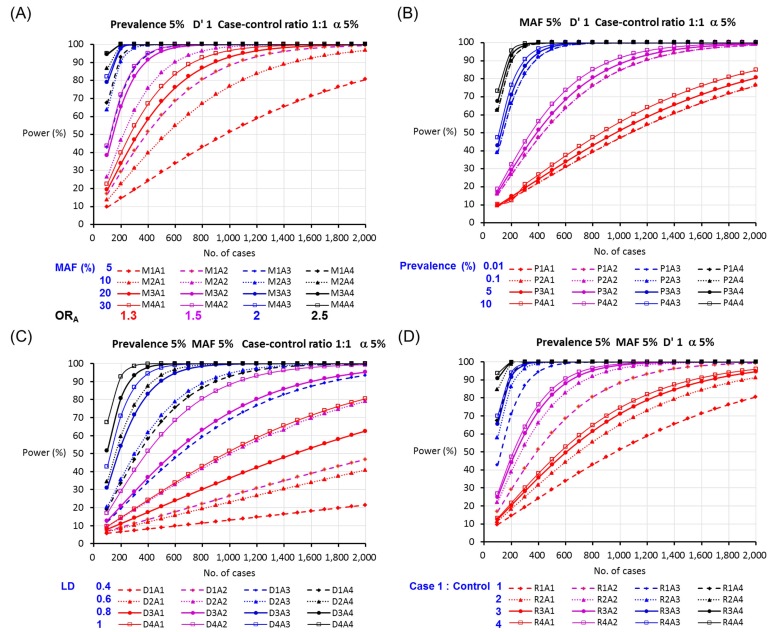

The sample size and statistical power for the allelic test in a case-control study under the different assumptions of ORhet, MAF, disease prevalence, LD, and case-to-control ratio by allowing a 5% type I error rate are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1A, a lower sample size was required to test allelic association for a single SNP with a larger MAF at the same risk of disease (OR) under the assumptions of 5% disease prevalence, 5% α, complete LD, and 1:1 case-to-control ratio. The minimum number of cases decreased from 1,974 cases for a SNP with a MAF of 5% to 545 cases for a SNP with a MAF of 30% under the same assumption. A high-risk allele showing a high OR requires a smaller sample size to be detected under the same assumption. While an allele with an OR of 1.3 requires 1,974 cases and 1,974 controls to be significantly detected in a case-control study, a SNP with an OR of 2.5 can be detected in a study of 134 cases and 134 controls under the assumption of a MAF of 5%, disease prevalence of 5%, type I error rate of 5%, and D' of 1 (Fig. 1A). The higher prevalence and the higher LD were associated with increased statistical power: for instance, as the LD increased from 0.4 to 0.6, 0.8, and 1, the statistical power obtained from a study of 1,000 cases and 1,000 controls was obviously increased from 26.5% to 49.2%, 72.8%, and 88.4%, respectively, under the assumption of OR 1.3, 5% MAF, 5% prevalence, and 5% α level (Fig. 1B and 1C). In addition, a 1:4 case-to-control ratio, which is the golden standard ratio for the numbers of cases and controls to be collected in a case-control study, showed the most effective sample size to achieve 80% statistical power. In many clinical settings, researchers are able to obtain more data from affected individuals than healthy individuals. On the other hand, there are more healthy participants than participants with a disease in a population-based study. Therefore, the minimum numbers of cases and controls required to achieve 80% statistical power depend on the study design. For a SNP with an allelic OR of 2 and 5% MAF, 127 cases and 508 controls are required in the case of a 1:4 case-control ratio, whereas 248 cases and 248 controls are required in the case of a 1:1 ratio to achieve 80% statistical power under the assumption of 5% prevalence, complete LD, and 5% α level.

Fig. 1.

The statistical power for the allelic test in a case-control study according to (A) minor allele frequency (MAF), (B) disease prevalence, (C) linkage disequilibrium (LD), and (D) case-to-control ratio (M, MAF; P, prevalence; D, LD; R, case-control ratio; A1=1.3, A2=1.5, A3=2, and A4=2.5 for heterozygous odds ratios).

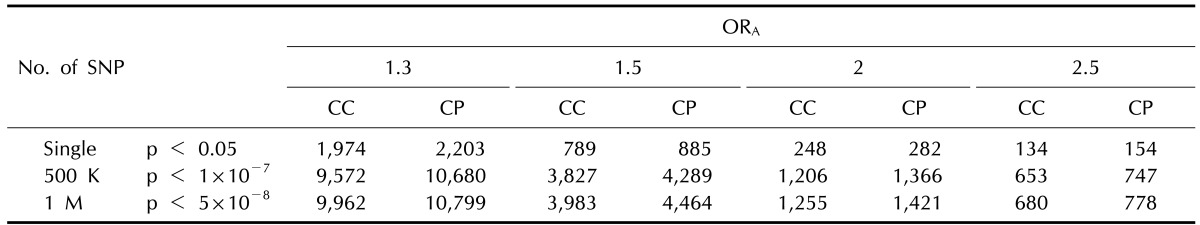

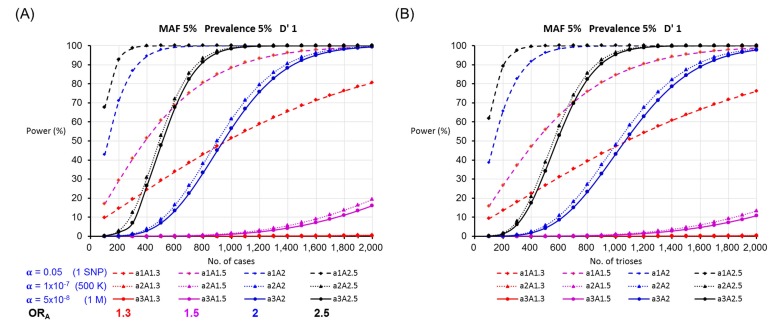

In Table 2, we compared the number of cases to the number of case-parent trios to perform a case-control study and a study using case-parent trios by increasing the number of SNPs being analyzed. Genetic association studies with larger numbers of SNP markers require a larger sample size to reduce false positive association due to testing multiple hypotheses. The sample size required in a case-parent study is generally larger than that of a case-control study design. For instance, 248 cases and 248 controls (496 individuals) were required to detect a SNP with an ORhet of 2 and 5% MAF in a case-control study, whereas 282 case-parent trios (846 individuals) were required under the assumption of 5% disease prevalence and complete LD by allowing a 5% α level. However, the sample sizes required in both study designs increase tremendously in a GWAS. Under the same assumptions as shown above, the number of samples increased from 248 cases for a single SNP analysis to 1,206 cases and 1,255 cases for analyses of 500 K SNPs and 1 M SNPs, respectively, based on the threshold of p-value, calculated using a strict Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses comparisons. The statistical power to test the same number of subjects was higher for the case-control design than for the case-parent trio design (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Sample sizes with 80% power by increasing number of SNP markers in case-control and case-parent studies

Assumptions: 5% minor allele frequency, 5% disease prevalence, complete linkage disequilibrium (D'=1), and 5% type I error rates for allelic test.

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; ORA, odds ratio of heterozygotes under an additive model; CC, case-control study; CP, case-parent study.

Fig. 2.

The statistical power according to the number of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers for the allelic test in (A) a case-control study and (B) a case-parent study (a1 = 0.05, a2 = 1×10-7, and a3 = 5×10-8 denote the significance thresholds according to the number of markers; A1.3, A1.5, A2, and A2.5 denote the odds ratios of heterozygotes). MAF, minor allele frequency; D', linkage disequilibrium.

Discussion

Both designs of the case-control study and case-parent study are used widely in the field of genetic epidemiology for studying associations between genetic factors and the risk of disease. Over the past 2 decades, there has been a steep increase in the number of genetic association studies, and these studies have successfully reported a number of gene variants associated with human complex diseases [1, 4, 5, 28]. Recently, GWASs, a new frontier in genetic epidemiology, have identified thousands of new gene variants related to human diseases [29]. The population-based studies with a large sample size have increased statistical power, which leads to smaller variance. However, it requires too much money and takes too long to collect a sufficient number of samples, and these large-scale studies are more likely to be affected by systematic bias and noise [25, 30].

In the current study, we demonstrated the effective sample sizes that are required to achieve 80% statistical power for a case-control study and case-parent study separately under various assumptions regarding effect size, MAF, disease prevalence, LD, case-to-control ratio, and number of SNPs. A lower sample size is required under the dominant model in any assumption, while the recessive model requires too many samples under the same assumptions to achieve adequate statistical power. Further, we confirmed that a lower sample size is required for testing more common SNPs with stronger effect sizes and increased LD between marker allele and disease allele. A lower sample size is required to study a common disease than a rare disease. The statistical power increases by increasing the number of controls per case; however, a case-to-control ratio exceeding 1:4 does not yield a significant increase in statistical power. Among the parameters tested, under the assumption of a high level of LD between a marker and disease variant, a much reduced sample size is needed to detect evidence for association. Common variants are more informative than rare variants in LD-based indirect association studies on complex diseases. It means that researchers can reduce the cost by choosing common variants to be genotyped at the design stage of an LD-based association study. In general, the case-control study design is more powerful than the case-parent study design [8, 10]. Since patients with family histories of the disease are more likely to inherit disease-predisposing alleles than patients without family histories of the disease, researchers can improve the statistical power by sampling patients with affected relatives and by comparing to controls without any family history in case-control association studies [13].

Genome-wide case-control studies have been used to identify genetic variants that predispose to human disease with model assumptions for parameters, such as the inheritance model. Such studies are powerful in detecting common variants with moderate effect in the occurrence of a disease; however, a study with a large number of SNP markers by using 500 K or 1 million chips requires a large number of samples (e.g., thousands of cases and controls) to achieve adequate statistical power. A researcher can rarely successfully conduct a large-scale association study without collaboration using a high-throughput microarray chip, in which most embedded SNPs reveal a small effect size between 1.3 and 1.6 [31]. Therefore, researchers who are planning a genetic association study must calculate the effective sample size and the statistical power in the design phase to perform a cost-effective study that reduces false negative and false positive test results. Although we could not cover all plausible conditions in study design, the estimates of sample size and statistical power that were computed under various assumptions in this study may be useful to determine the sample size in designing a population-based association study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0090837).

References

- 1.Cardon LR, Bell JI. Association study designs for complex diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:91–99. doi: 10.1038/35052543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon D, Finch SJ, Nothnagel M, Ott J. Power and sample size calculations for case-control genetic association tests when errors are present: application to single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Hered. 2002;54:22–33. doi: 10.1159/000066696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschhorn JN, Lohmueller K, Byrne E, Hirschhorn K. A comprehensive review of genetic association studies. Genet Med. 2002;4:45–61. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scherag A, Müller HH, Dempfle A, Hebebrand J, Schäfer H. Data adaptive interim modification of sample sizes for candidate-gene association studies. Hum Hered. 2003;56:56–62. doi: 10.1159/000073733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunetta KL. Genetic association studies. Circulation. 2008;118:96–101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.700401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon D, Levenstien MA, Finch SJ, Ott J. Errors and linkage disequilibrium interact multiplicatively when computing sample sizes for genetic case-control association studies. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2003:490–501. doi: 10.1142/9789812776303_0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH. Sample size calculations for population- and family-based case-control association studies on marker genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:136–148. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Risch N, Teng J. The relative power of family-based and case-control designs for linkage disequilibrium studies of complex human diseases I. DNA pooling. Genome Res. 1998;8:1273–1288. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risch NJ. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature. 2000;405:847–856. doi: 10.1038/35015718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Oord EJ. A comparison between different designs and tests to detect QTLs in association studies. Behav Genet. 1999;29:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hintsanen P, Sevon P, Onkamo P, Eronen L, Toivonen H. An empirical comparison of case-control and trio based study designs in high throughput association mapping. J Med Genet. 2006;43:617–624. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buyske S, Yang G, Matise TC, Gordon D. When a case is not a case: effects of phenotype misclassification on power and sample size requirements for the transmission disequilibrium test with affected child trios. Hum Hered. 2009;67:287–292. doi: 10.1159/000194981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng B, Li B, Han Y, Amos CI. Power analysis for case-control association studies of samples with known family histories. Hum Genet. 2010;127:699–704. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0824-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein RJ. Power analysis for genome-wide association studies. BMC Genet. 2007;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zondervan KT, Cardon LR. Designing candidate gene and genome-wide case-control association studies. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2492–2501. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer CC, Su Z, Donnelly P, Marchini J. Designing genome-wide association studies: sample size, power, imputation, and the choice of genotyping chip. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z, Zhao H. Statistical power of model selection strategies for genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JH, Wacholder S, Gail MH, Peters U, Jacobs KB, Chanock SJ, et al. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide association studies and implications for future discoveries. Nat Genet. 2010;42:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park AK, Kim H. A review of power and sample size estimation in genomewide association studies. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007;40:114–121. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2007.40.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitley E, Ball J. Statistics review 4: sample size calculations. Crit Care. 2002;6:335–341. doi: 10.1186/cc1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comeron JM, Kreitman M, De La Vega FM. On the power to detect SNP/phenotype association in candidate quantitative trait loci genomic regions: a simulation study. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2003:478–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satagopan JM, Venkatraman ES, Begg CB. Two-stage designs for gene-disease association studies with sample size constraints. Biometrics. 2004;60:589–597. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn C. Sample size and power estimation in case-control genetic association studies. Genomics Inform. 2006;4:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menashe I, Rosenberg PS, Chen BE. PGA: power calculator for case-control genetic association analyses. BMC Genet. 2008;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laurie CC, Doheny KF, Mirel DB, Pugh EW, Bierut LJ, Bhangale T, et al. Quality control and quality assurance in genotypic data for genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:591–602. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houle TT, Penzien DB, Houle CK. Statistical power and sample size estimation for headache research: an overview and power calculation tools. Headache. 2005;45:414–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS. A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1590–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI34772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirschhorn JN. Genomewide association studies: illuminating biologic pathways. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1699–1701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0808934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Wang Y, Rekaya R, Sriram TN. Sample size determination for classifiers based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Biostatistics. 2012;13:217–227. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxr053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, Ramos EM, Mehta JP, Collins FS, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9362–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]