Abstract

Background

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is underutilized, in part because of costs and time requirements. This study extends pilot work investigating the use of a stepped care ERP administration, in which patients are first given a low-intensity, low-cost treatment and the more costly intervention is reserved for those who do not respond to the first intervention.

Methods

Thirty adults with OCD were randomized to receive stepped care ERP or standard ERP. Those receiving stepped care started with three sessions over 6 weeks of low-intensity counseling with ERP bibliotherapy; patients failing to meet strict responder criteria after 6 weeks were given the more traditional treatment of therapist-administered ERP (17 sessions twice weekly). Those receiving standard ERP received the therapist-administered ERP with no lower-intensity lead-in.

Results

The two treatments were equally efficacious, with 67% of stepped care completers and 50% of standard treatment completers meeting criteria for clinically significant change at posttreatment. Similarly, no differences in client satisfaction ratings were obtained between the two groups. Examination of treatment costs, however, revealed that stepped care resulted in significantly lower costs to patients and third-party payers than did standard ERP, with large effect sizes.

Conclusions

These results suggest that stepped care ERP can significantly reduce treatment costs, without evidence of diminished treatment efficacy or patient satisfaction. Additional research is needed to determine the long-term efficacy and costs of stepped care for OCD, and to examine the financial and therapeutic impact of implementing stepped care in community settings.

Keywords: obsessive–compulsive disorder, stepped care, exposure and response prevention, behavior therapy, cost-effectiveness, health economics

INTRODUCTION

Although numerous studies attest to the efficacy of cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) incorporating exposure and response prevention (ERP) for patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)[1–5] and Expert Consensus Guidelines[6–8] list ERP as a first-line treatment for OCD, this treatment is underutilized in the community. In the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project,[9] only 56% of OCD patients reported receiving any kind of behavior therapy other than relaxation training, which has not been shown to be efficacious for OCD. In a large-scale survey of individuals with OCD,[10] only 60% were receiving treatment; of those, only 53% (32% of the total sample) were receiving any form of CBT (by contrast, 67% were receiving “talk therapy,” which has not been shown to be efficacious for OCD).

A possible explanation for the under-utilization of ERP for OCD is the perception that this treatment is not cost-effective. The treatment sessions are time consuming, requiring an estimated 30 hr of direct clinician time, and expensive (in the short term), with a 1995 survey showing an average cost of $4,370 ($6,304 in 2010 dollars).[11] Thus, many patients and third-party payers may not be able or willing to pay for treatment. In the aforementioned survey of individuals with OCD, the most commonly reported barriers to seeking treatment included cost (57%), insurance coverage (38%), and time requirements (31%).[10] Relatedly, ERP is relatively difficult for many patients to obtain due to a limited number of well-trained professionals; specialized training in ERP is not a component of most graduate programs in psychology.[12,13]

Thus, there is a clear need to explore alternative delivery systems of ERP for OCD which can provide the most effective treatment components in a manner that is more accessible, less time-consuming, and less costly to patients and third-party payers. The explicit aim of such a program would be to maximize the accessibility and cost-effectiveness of treatment, thus allowing more patients to receive this evidence-based intervention.

We and other researchers have investigated less expensive treatment options for OCD such as self-help with minimal therapist contact,[14,15] computer-assisted ERP,[16] and group ERP.[17] Each of these methods shows promise; however, their utility is limited by the inability to self-correct by providing patients with their optimal level of treatment and no more. Thus, we propose that a model of stepped care may be a more appropriate strategy for maximizing cost-effectiveness. The general principle of stepped care is that all patients are first given the least expensive and least restrictive treatment. Those patients who do not respond to the initial treatment are offered a more expensive (but potentially more effective) option. The stepped care model is particularly advantageous in its ability to identify the least restrictive and least costly workable intervention for each individual patient.[18,19]

The stepped care protocol was developed over the course of two open trials.[20,21] In the first of these,[21] 11 patients completed a three-step program (step 1 bibilotherapy, step 2 bibliotherapy plus counseling, step 3 standard ERP for 12 90–120 min sessions). Results of this study were promising, with stepped care demonstrating comparable treatment efficacy and superior cost-effectiveness to previously published studies utilizing traditional ERP.

Results of the first open trial informed a decision to condense the three-step protocol to two steps, given that only a 3.5% OCD symptom reduction (d=.07), as measured by the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), was observed between step 1 and step 2. Therefore, in the second open trial,[20] 14 participants completed a two-step program (step 1 bibliotherapy plus counseling, step 2 standard ERP for 12 90–120 min sessions). The two-step program was efficacious (Y-BOCS improvement=60% for completers and 51% for ITT sample; 88% of treatment completers were rated as much or very much improved) and cost-effective. Rough cost-effectiveness ratios were derived for both the intent to treat and completer sample by dividing the direct costs of treatment (based on Medicare reimbursement rates) by change in Y-BOCS scores from pretreatment to posttreatment. Results showed the cost-effectiveness ratio in this study was superior to that reported in our first open trial of stepped care, suggesting that condensing the steps had improved cost-effectiveness of the treatment.

Importantly, the cost-effectiveness ratio of stepped care was equal to or better than those calculated from other studies of therapist-directed ERP.[17,22,23] As one example, in Foa et al.’s[1] intensive ERP program, the average direct cost of reducing the Y-BOCS by one point was $237. Conversely, in our studies of stepped care, the average direct cost of reducing the Y-BOCS by one point ranged from $63 to $103. However, stepped care and standard ERP have not yet been compared to each other in a controlled trial. The aim of this study was to directly compare the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of stepped care and standard ERP for patients with OCD. It was predicted that although the two treatments would be comparable in efficacy, stepped care would prove more cost-effective (i.e., less costly).

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

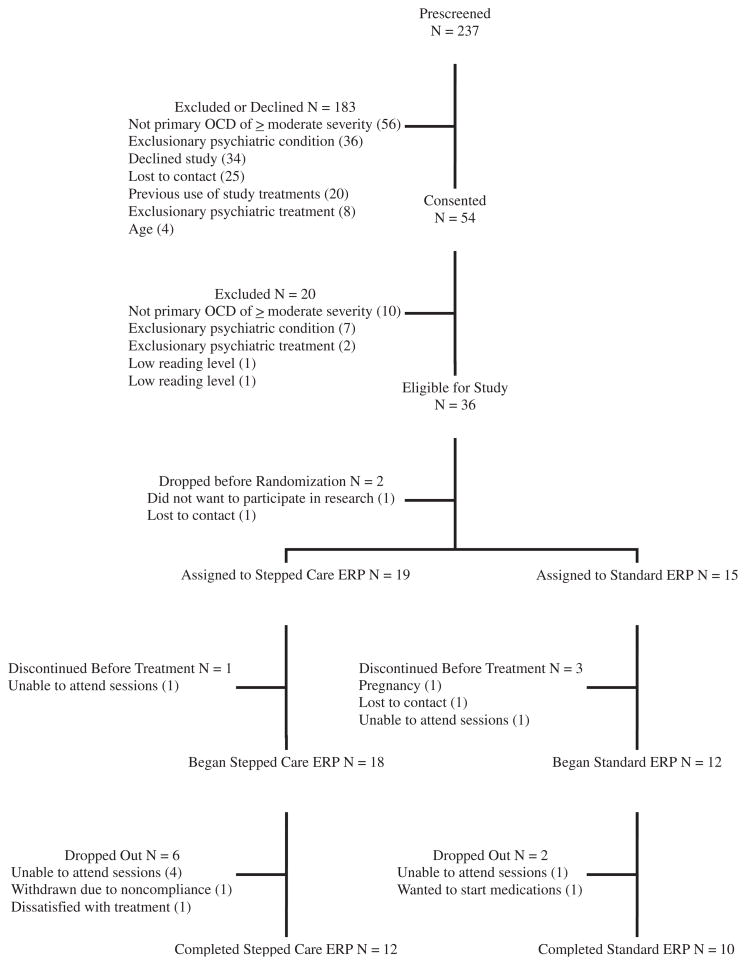

A flow chart of patient enrollment and retention is shown in Figure 1. Thirty patients received stepped care ERP (n=18) or standard ERP (n=12). Inclusion criteria for enrollment were: age 18 or older, primary DSM-IV-TR[24] diagnosis of OCD with a least 1 year symptom duration and moderate illness severity, as determined by a Y-BOCS[25,26] score of 16 or greater and Clinician’s Global Impression scale (CGI)[27] score of 4 (“moderately ill”) or greater. Participants who were taking psychiatric medications were stable on medication for at least 1 month and agreed to maintain their current type and dose of medication, with their physician’s approval. Participants were not in concurrent psychotherapy, and had not already received an adequate trial of therapist-directed ERP or ERP-focused bibliotherapy. Exclusionary criteria included any concurrent symptoms or diagnosis that required immediate attention and/or would interfere with the patient’s ability to engage in treatment, such as severe depression, serious suicidal or homicidal ideation, substance abuse/dependence, or lifetime diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, or mental retardation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of enrollment.

MATERIALS

Clinical measures

Axis I psychiatric diagnoses were ascertained using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM—IV (ADIS-IV),[28] a semistructured interview with good psychometric properties. Raters for this study were trained to criterion in the use of the ADIS-IV, with the requirement of 100% diagnostic match and within one point clinical severity rating with a previously trained rater on three interviews. During our pilot research, we obtained perfect interrater agreement for the diagnosis of OCD and other anxiety disorders (κ=1.0), although there was one instance of diagnostic disagreement for a depressive disorder.[20] Axis II diagnoses were determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II),[29] a semistructured interview with acceptable inter-rater reliability.[30,31] Following standard clinical protocol,[32] the SCID-II modules were administered only to patients endorsing symptoms on the SCID-II Screen Questionnaire. OCD symptom severity was assessed using the Y-BOCS,[25,26] a 10-item semistructured interview. Evaluators for this study were trained to criterion to administer the Y-BOCS, with the requirement that they match within one point on each item and within two points on the total score with a previously trained rater. Internal consistency (α) in this sample was .74 and inter-rater reliability (ICC) in the pilot study was .71.[20] We also used the self-report version of the Y-BOCS (YBOCS-SR)[33] for ongoing monitoring during treatment; internal consistency (α) in this sample was .86. The clinician and self report Y-BOCS were significantly correlated at pretreatment (r=.70, P<.001), poststep 1 (r=.85, P<.001), poststep 2/standard ERP (r=.83, P<.001), 1 month follow-up (r=.74, P<.001), and 3-month follow-up (r=.93, P<.001). Global severity of illness was rated using the CGI,[27] composed of a severity subscale (CGI-S), which ranges from 1 (normal, not at all ill) to 7 (extremely ill), and an improvement subscale (CGI-I), which ranges from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). Reading skills were assessed with the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading;[34] 1 participant was excluded based on low WTAR score. General psychological distress was measured using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale,[35] a 42-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress over the past week on a four-point scale. The DASS possesses good psychometric properties.[36,37] Internal consistency (α) in this sample was .92 for the stress and depression subscales, and .66 for the anxiety subscale.

Process measures

Treatment credibility and patient expectations were assessed using the Expectancy Rating Form (ERF),[38] a self-report measure with a score range from 0 (not at all) to 32 (extremely), with higher scores indicating higher expectancies. Internal consistency (α) for this sample was .71 at step 1 and .82 at step 2/Standard ERP. Patients and clinicians rated treatment compliance using a Homework Compliance Rating Form created for this study. Participants rated their homework compliance on a weekly basis during step 1, and at each session (i.e., twice weekly) during step 2. They rated, on a scale from 0 to 5, the amount of effort they put into ERP assignments (0=no effort, 5=best effort), and how much time they spent on exposures each day outside of the treatment sessions (0=none, 5=more than 2 hr). During step 1, participants were also asked to rate how much of the assigned reading they completed on a scale from 0 (none) to 5 (all). Questions regarding effort and time spent on ERP were not asked during the first 2 weeks of step 1, as ERP was not assigned during the first 2 weeks. Therapists rated participants’ degree of effort on the same five-point scale described above. In a previous study at this research site,[39] inter-rater reliability of this rating between the clinician and clinical supervisor was r=.82. Satistfaction with each phase of treatment was measured with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ),[40] an 8-item self-report measure with good psychometric properties.[41] Internal consistency (α) for this sample was .93 at step 1, .88 at step 2/Standard ERP, .92 at 1-month follow-up, and .93 at 3-month follow-up.

Cost measures

Treatment costs included both direct and indirect costs, measured according to current standards in the field of health economics.[42] Direct costs to patients included all deductible and coinsurance payments. Direct cost to third party payers of medical services related to the administration of treatment including therapy visits and self-help materials. Therapy visits were valued at the Medicare reimbursement rate[43] for psychologist visits (CPT code 90804 for a 20–30min therapy session, CPT code 90806 for each 45–50min of face-to-face therapy time). Direct cost of each step 1 session was calculated as a 90804, and each step 2 or standard treatment session was calculated as two sessions of 90806. Total direct cost was calculated as the sum of patient and payer direct costs. Indirect costs to patients included the cost of travel and lost wages from time spent in treatment. Transportation costs were estimated based on mileage to and from the patient’s home to the clinic. Three types of time costs were collected: travel time to and from the clinic, waiting time at the clinic, and visit time. Length of each protocol visit was recorded. Lost wages associated with treatment were calculated by totaling the amount of time each patient spent in treatment sessions, traveling to and from treatment, and waiting for treatment sessions and multiplying the sum by the median US hourly wage in 2008 of $15.57.[44] Indirect costs to providers included labor cost (based on the cost of a portion of a 90806) not reimbursed by insurance, such as preparing for sessions, and cost of travel for off-site sessions. The total cost was calculated by summing all direct and indirect costs to patients, payers, and providers.

PROCEDURE

Assessment

After providing written informed consent, prospective patients met with an independent evaluator (IE) who was unaware of treatment assignments. The IE (a Ph.D. clinical psychologist or a postdoctoral fellow trained to criterion in the study measures and experienced in the assessment of OCD) administered a packet of questionnaires, as well as the ADIS-IV, SCID-II, Y-BOCS, CGI-S, and WTAR. Patients meeting study inclusion criteria were then referred to a study therapist, who informed the patient of their randomly assigned treatment condition.

Stepped care

The therapist administered the ERF after the first treatment session. The stepped care treatment began with bibliotherapy plus counseling (step 1). Patients were given a copy of the book “Stop Obsessing!”[45] and were provided with a schedule of reading over a 6-week period (the time allotment was derived from therapist and patient feedback in our pilot research). The book is organized into three sections: Understanding Your Problem, The Initial Self-Help Program, and The Intensive Three-Week Program (which focuses on ERP). Based on our experience in the open trials, we organized the reading schedule to emphasize self-administered ERP. During step 1, participants also met with the therapist three times (one 30–40min visit every 2 weeks). The therapist’s function was to provide support and examine sources of life stress. In addition, the therapist used motivational interviewing techniques[46] to address ambivalence about change. The therapist answered questions regarding ERP, and provided suggestions for implementing ERP; however, no ERP was performed or modeled within these sessions. Patients completed the YBOCS-SR at each visit. They were instructed to contact their therapist if they experienced an increase in their OCD or depressive symptoms, or suicidal ideation, at which time an as-needed IE visit would be scheduled. Any patients whose Y-BOCS scores showed clinically significant[47] worsening were considered for immediate entry into step 2 (this did not occur during the study). An independent doctoral-level rater (a Ph.D. clinical psychologist who was trained to criterion, had several years’ specialized experience in CBT for OCD, and had served as a study clinician and clinical trainer in a previous trial of stepped care for OCD) listened to 11 step 1 audiotaped sessions and rated therapists’ competence as 7.91 (good to excellent) on a 0–8 scale and therapists’ adherence as 8.00 (optimal) on a 0–8 scale.

After step 1, patients met again with the IE, who re-administered the Y-BOCS. To determine whether a patient should move on to the next step of treatment, we used the criterion of clinically significant change (CSC)[47] on the Y-BOCS. The most commonly used and widely accepted[48] operational definition of CSC was described by Jacobson and Truax[49] as a posttreatment test score (in this case, the Y-BOCS) that: (a) has decreased by a reliable level (at least 1.96 times the standard deviation of that measure, taking into account the reliability of the measure itself; in this case, a decrease of five points or more) and (b) is within the nonclinical range of scores (or no longer in the clinical range of scores). Given the concern about false positives (i.e., identifying a patient as a responder when he/she has not in fact had a clinically meaningful response and thus terminating their treatment prematurely), we opted to use a conservative cut-off score of 13 or below. This score is comparable to other definitions of clinical remission[50] and these responder criteria were validated in our pilot studies.[20,21] Our pilot data have also demonstrated high concordance (86% agreement) between this CSC criterion and treatment responder status as measured by the CGI, with all disagreements showing that CSC was more conservative than the CGI.[20] Thus, a patient advanced from step 1 to step 2 only if he/she did not meet criteria for CSC at the end of step 1. If the patient did meet criteria for CSC, he/she received ongoing monitoring, but no further treatment (although a clinically significant worsening of OCD symptoms at the next assessment would merit entry to step 2; this occurred with one patient at the 3-month follow-up, although she declined entry into step 2).

Patients continuing to step 2 (i.e., those that had not shown CSC on the Y-BOCS after step 1) again completed the ERF after the first treatment session. These patients received therapist-directed ERP, based on a published manual[51] used in several prior studies.[1,15,39,52] Step 2 consisted of 17 outpatient treatment sessions lasting 90–120 min each. Treatment began with information gathering and treatment planning, during which the patient’s symptoms were assessed in detail and an exposure hierarchy was created. ERP was then provided twice weekly, a schedule that is both feasible in many clinical settings and appears to equal more intensive schedules in efficacy.[22] ERP consisted of graded exposure to the items on the hierarchy, combined with strict abstinence from compulsive behavior. In the final session, relapse prevention was reviewed and guidelines developed to assist the patient in managing his/her symptoms without relying on the therapist. Using the same adherence and competence ratings described above, mean therapist competency rating was 7.89 on a 0–8 scale and mean adherence rating was 7.67 on a 0–8 scale for step 2. Patients completed the YBOCS-SR at every other visit.

Standard ERP

Patients assigned to the standard ERP condition received ERP that was identical to that described in step 2 of the stepped care condition. Mean therapist competency rating was 7.50 on a 0–8 scale and mean therapist adherence rating was 7.70 on a 0–8 scale.

Posttreatment and follow-up assessment

Following completion of stepped care or standard ERP, patients met again with the IE who administered the Y-BOCS, CGI-S, and CGI-I.

Data analysis

The two primary outcomes were efficacy (as measured by the Y-BOCS) and cost (as measured by the various indices described above). Intent-to-treat mixed-model analyses were used to account for missing data. Various covariance types were tried, with the best-fit solution identified as that producing the smallest value of Schwarz’s Bayesian Criterion. The use of cost, rather than cost-effectiveness ratios, as a dependent variable was predicated on the absence of a difference in efficacy (see below).

RESULTS

SAMPLE DESCRIPTION

As shown in Table 1, patients in the two conditions did not differ significantly in terms of age, sex, race/ethnicity, global severity of illness, estimated IQ, use of medications, presence of comorbid diagnosis, or severity of OCD or anxiety symptoms. Average OCD symptoms were in the severe range for both groups. Standard ERP patients reported marginally (P=.055) higher levels of depression than did stepped care patients.1 Overall, 23 (68%) of the sample met criteria for at least one comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, most commonly anxiety and depressive disorders; 47% of the sample was currently taking SRI antidepressants and 56% had had at least one prior SRI trial.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics

| Stepped care (N=19) | Standard ERP (N=15) | t (32) | χ2(1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [M (SD)] | 35.95 (15.16) | 31.33 (10.50) | 1.00 | |

| Female [N (%)] | 13 (68.4%) | 7 (46.7%) | 1.64 | |

| White [N (%)] | 15 (78.9%) | 9 (60.0%) | 1.45 | |

| Y-BOCS [M (SD)] | 23.95 (4.50) | 25.86 (4.31) | 1.23 | |

| DASS Depression [M (SD)] | 5.84 (5.42) | 11.00 (9.17) | 2.00a | |

| DASS Anxiety [M (SD)] | 5.11 (4.16) | 7.64 (4.36) | 1.70 | |

| DASS Stress [M (SD)] | 10.32 (7.21) | 14.92 (9.34) | 1.57 | |

| WTAR [M (SD)] | 111.26 (18.26) | 114.20 (8.14) | 0.58 | |

| CGI-S [M (SD)] | 4.74 (0.73) | 5.07 (0.88) | 1.19 | |

| Comorbid Diagnosis [N (%)] | 12 (63.2%) | 11 (73.3%) | 0.40 | |

| Current SRI Trial [N (%)] | 9 (47.4%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0.00 | |

| Prior SRI Trial [N (%)] | 10 (52.6%) | 9 (60.0%) | 0.18 |

P=.055.

EFFICACY

The Y-BOCS was used to examine the efficacy of stepped care versus standard ERP. The 2 (group: stepped care, standard ERP)×3 (time: pretreatment, posttreatment, 3-mo FU) mixed-factor GLM, with time as the repeated measure revealed only a significant main effect of time (F2,71.71=32.04, P<.001). The group×time interaction was not significant (F2,71.71=0.88, P=.419) and the main effect of group was not significant (F1,53.92=0.38, P=.541). Thus, both stepped care and standard ERP were efficacious, but there was no apparent difference in efficacy between the two (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Mean (SD) Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Scores for patients receiving stepped care versus standard exposure and response prevention (ERP) at pretreatment, posttreatment, and follow-up

| Pre | Post | 3-Month FU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stepped care ERP | 24.47 (5.54) | 15.16 (5.54) | 13.87 (6.26) |

| Standard ERP | 26.00 (5.54) | 14.25 (6.19) | 15.75 (6.40) |

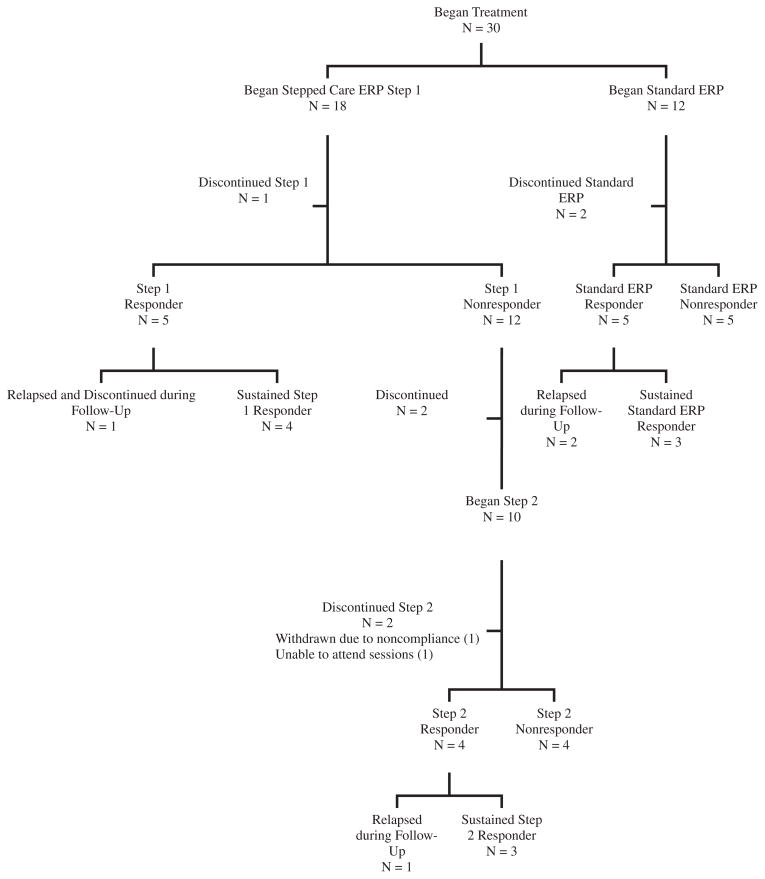

Rates of treatment response (stringently defined as CSC on the Y-BOCS) were also compared between the stepped care and standard ERP groups (Fig. 2). Among treatment completers, there were no significant differences in response rates at posttreatment [67% stepped care versus 50% standard ERP, χ2(1, 22)=0.63, P=.43], 1-month follow-up [73% stepped care versus 60% standard ERP, χ2(1, 21)=0.38, P=.54], or 3-month follow-up [50% stepped care versus 40% standard ERP, χ2(1, 22)=0.22, P=.64]. Similarly, no significant differences in response rates were found for the intent to treat sample at posttreatment [50% stepped care versus 42% standard ERP, χ2(1, 30)= 0.20, P=.66], 1-month follow-up [56% stepped care versus 58% standard ERP, χ2(1, 30)=0.23, P=.88], or 3-month follow-up [44% stepped care versus 42% standard ERP, χ2(1, 30)=0.23, P=.88].

Figure 2.

Flow chart of response rates.

Expectancy, compliance, and satisfaction

In order to examine any potential differences in client satisfaction between those who received stepped care versus those who received standard ERP, three separate t-tests were conducted on total scores of the CSQ. Results revealed no significant differences in client satisfaction between stepped care and standard ERP participants at all time points [Posttreatment (t27=−.47, P=.64), 1-month follow-up (t23=−.19, P=.85), or 3-month follow-up (t21=.07, P=.95). Mean scores on the CSQ ranged from 29.00 to 29.92 between the two treatment conditions across all assessment time points.

ERF scores revealed that participants reported moderate expectations of success for each treatment step. Mean total scores on the ERF were 23.95 (SD=4.52) for step 1 and 25.87 (SD=3.47) for step 2/Standard ERP. Mean clinician rating of participant’s overall effort was 2.54 (SD=0.71) for step 1 and 2.56 (SD=.87) for step 2/Standard ERP, which corresponds to putting forth “some” to “much effort” into ERP. During step 1, participants reported reading “half” to “most” (M=3.48; SD=1.34) of the assigned reading. They reported spending approximately 30 min to one hour daily on ERP (M=2.08; SD=1.11), and described putting an “average” amount of effort during step 1 (M=2.99; SD=1.01). During step 2, participants reported spending approximately 60–90 min daily on ERP (M=2.88; SD=0.95) and putting forth an “average” to “a lot” of effort into ERP (M=3.41; SD=0.77).

Cost

Treatment costs, rather than cost-effectiveness ratios, were compared between the two groups. Calculation of a cost-effectiveness ratio is predicated on an obtained difference in treatment efficacy between the two treatment conditions. In the absence of such a difference (see above), cost-effectiveness is determined by directly comparing treatment costs.

Examining cost from a fixed-dose perspective (i.e., treatment ends when the patient reaches a certain number of sessions), stepped care was significantly less expensive to administer (and therefore was more cost-effective) than was standard ERP, with a large effect size.[53] More fine-grained analysis suggested that the overall difference in costs was related to direct costs to patients and payers, as well as indirect costs to patients (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Differential costs between stepped care and standard exposure and response prevention (ERP), fixed dose

| Stepped care | Standard ERP | t (28) | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient direct cost | $759.03 (697.66) | $1,291.52 (350.35) | 2.76* | 0.96 |

| Payer direct cost | $1,686.74 (1,550.36) | $2,870.05 (778.56) | 2.76* | 0.96 |

| Total direct cost | $2,445.77 (2,248.03) | $4,161.57 (1,128.91) | 2.76* | 0.81 |

| Patient indirect cost | $454.93 (424.78) | $752.87 (295.63) | 2.27* | 0.37 |

| Provider indirect cost | $220.95 (293.58) | $308.36 (163.75) | 1.04 | 0.94 |

| Total cost | $3,121.65 (2,826.93) | $5,222.80 (1,429.15) | 2.68* | 0.96 |

Note:

Patient direct cost=deductible and coinsurance paid by patient; Payer direct cost=cost of session paid by third party payer (e.g. Medicare, commercial insurance); Total direct cost=the combination of patient and payer direct costs; Patient indirect cost=indirect costs of participating in treatment, including cost of travel and lost wages from time spent in treatment, driving to and from treatment, or waiting for treatment session; Provider indirect costs=abor cost not reimbursed by insurance, such as preparing for session, and cost of travel for off-site sessions; Total cost=Total cost of treatment including all direct and indirect costs to patient, payer, and provider.

P<.05.

Careful examination of weekly patient data showed that many of the stepped care patients had responded early (e.g., within two sessions) in step 2, yet remained in the fixed-dose treatment due to protocol requirements. This finding led us to consider an exploratory analysis using a flexible-dose treatment schedule, in which treatment is terminated once the patient reaches a predetermined criterion [in this case, responder status using CSC]. Such a schedule would more closely resemble treatment decision-making in a naturalistic treatment setting. We therefore reanalyzed the cost data using the session at which patients met criteria for CSC as the end of treatment data point. As shown in Table 4, these data demonstrated that stepped care remained significantly less costly than standard ERP, with similarly large effect sizes and lower overall costs in both conditions.

TABLE 4.

Differential costs between stepped care and standard exposure and response prevention (ERP), flexible dose

| Stepped care | Standard ERP | t (28) | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient direct cost | $584.95 (635.38) | $1,037.45 (452.66) | 2.12* | 0.82 |

| Payer direct cost | $1,299.88 (1,411.96) | $2,305.45 (1,005.91) | 2.12* | 0.82 |

| Total direct cost | $1,884.83 (2,047.35) | $3,342.90 (1,458.58) | 2.12* | 0.82 |

| Patient indirect cost | $377.98 (424.71) | $628.69 (365.04) | 1.67 | 0.63 |

| Provider indirect cost | $216.80 (280.85) | $308.24 (163.85) | 1.02 | 0.40 |

| Total cost | $2,479.62 (2,555.75) | $4,279.84 (1,822.53) | 2.10* | 0.81 |

Note:

Patient direct cost=deductible and coinsurance paid by patient; Payer direct cost=cost of session paid by third party payer (e.g. Medicare, commercial insurance); Total direct cost=the combination of patient and payer direct costs; Patient indirect cost=indirect costs of participating in treatment, including cost of travel and lost wages from time spent in treatment, driving to and from treatment, or waiting for treatment session; Provider indirect costs=Labor cost not reimbursed by insurance, such as preparing for session, and cost of travel for off-site sessions; Total cost=Total cost of treatment including all direct and indirect costs to patient, payer, and provider.

P<.05.

DISCUSSION

Problems in disseminating evidence-based ERP for OCD into community settings may relate in part to the intensity and cost of that treatment. A stepped care approach, in which low-cost counseling with bibliotherapy are tried before the higher-cost therapist-administered treatment, may present a useful alternative. The present results suggest that a stepped-care approach to ERP can significantly reduce treatment costs to patients and to third-party payers, without evidence of diminished treatment efficacy or patient satisfaction. It could be argued that between-group efficacy differences (favoring standard treatment at posttreatment and favoring stepped care at follow-up) would have been detected with a larger sample size. Although post hoc power analyses are not recommended,[ 54] replication in a larger sample is needed before more conclusive statements about relative efficacy can be made.

It is reasonable to predict that lowering the overall cost and intensity of ERP, such as with a stepped care implementation, would result in several positive changes, all of which await empirical examination. First, lower time and financial burden to patients would be expected to result in a greater number of prospective patients seeking out and accepting this evidence-based treatment. Second, lower direct costs to third-party payers may make ERP a more attractive option, leading to improved parity for behavioral therapy. Third, the lower clinician time demands of stepped care versus standard ERP would allow trained clinicians (of whom there is currently a noteworthy shortage) to see a larger volume of patients, while reserving

By virtue of its flexibility, stepped care may have advantages over other cost-saving strategies such as self-help with minimal therapist contact,[14,15] computer-assisted ERP,[16] and group ERP.[17] In a stepped care protocol, the intensity of treatment is adjusted so that each patient receives his/her optimal level of treatment and no more, thereby providing each patient with his/her least costly workable intervention. Similarly, the flexible approach to overall treatment discontinuation explored in this study, in which treatment stops at the point of CSC, appears to be a promising means of reducing costs further. However, the design of this study, in which all treatments were delivered according to a fixed dose, does not allow for a clear understanding of longer-term effects and relapse rates under a flexible termination schedule.

Despite the appeal of stepped care for OCD and the promising results of this study, it is important to recognize that starting with lower-cost treatment options might not always be the most cost-effective strategy. This fact is highlighted in a recent study of stepped care pharmacotherapy for depression, in which lower cost generic medications were used first, and more expensive medications reserved for step 1 nonresponders. Although the direct costs of antide-pressant therapy were lower for patients receiving stepped care, the delay in effective treatment led to increased inpatient and emergency room utilization, resulting in higher overall costs.[55] Two lessons can be learned from that study. First, it is important that any cost-effectiveness analysis incorporates estimates not only of treatment costs but also of other health-care utilization and cost of illness. Additional research, examining overall health care expenditures over a longer period of time, is needed. Second, there is a need to determine a priori which patients are best matched to a stepped care program. In many areas of mental health treatment (including OCD), the relevant variables for patient-treatment matching are as yet unknown. For example, based on previous research, it might be expected that patients with average or better neurocognitive functioning, less severe depression, and high levels of motivation for change would possess the necessary initiative, comprehension, and self-regulation to benefit from a self-directed bibliotherapy intervention as is administered in the stepped care program. Certain OCD symptom dimensions, such as scrupulosity and hoarding, which have proven less responsive to ERP, might prove especially difficult to address with stepped care, although this is speculative. The small sample size of this study precludes accurate understanding of differential treatment predictors, although we are currently conducting exploratory analyses using combined data sets from multiple studies of stepped care ERP. Additional research is needed to determine predictive guidelines and algorithms for personalizing treatment.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the sample size was relatively small (N=30), rendering any conclusions tentative. A larger randomized trial is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached. Second, as noted previously, the cost analyses did not account for utilization of other forms of health care. Third, the follow-up period was only 3 months, and it is not clear whether the obtained cost savings and similar efficacy would have been maintained over a longer period. Fourth, the 23% attrition rate is noted; although this figure is comparable to that reported in other ERP trials (e.g., 28% for Foa et al.[1]), it could diminish the generalizability of findings. Fifth, it is noted that although patients in the two groups had equivalent OCD symptom severity, marginally higher depression scores were noted in the standard ERP group. This trend toward more severe depression could have confounded the results given the small sample size. Finally, this study was conducted under controlled circumstances (e.g., patients were instructed to hold medications stable during the trial, and certain individuals were excluded from the study for a variety of reasons), and it remains unclear how the present findings would translate into “real-world” outcomes in broad clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors disclose the following financial relationships within the past 3 years: Contract grant sponsor: NIMH; Contract grant number: R34 MH071464.

The authors thank Drs. Edna Foa, Stewart Agras, Linda Frisman, Suzanne Gleason, and Ralitza Gueorguieva for their consultation throughout the study. Dr. Sabine Wilhelm, Dr. Gregorio Febbraro, and David O’Sullivan served as the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Sara Whiting and Christina Ryan served as research assistants. In addition to the authors, Drs. Elizabeth Moore, Anna Villavicencio, and Samantha Morrison served as study therapists and/or independent evaluators. Dr. Raveen Mehendru provided medical oversight for the study. This study was supported by NIMH grant R34 MH071464 to Dr. Tolin.

Footnotes

Depression scores did not correlate significantly with the main outcome measures: Y-BOCS change (r=−.22, P=.366) or treatment cost (r=.001, P=.996). Therefore, depression was not used as a covariate in the analyses.

References

- 1.Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151–161. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottraux J, Mollard E, Bouvard M, Marks I. Exposure therapy, fluvoxamine, or combination treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: one-year followup. Psychiatry Res. 1993;49:63–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(93)90030-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fals-Stewart W, Marks AP, Schafer J. A comparison of behavioral group therapy and individual behavior therapy in treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:189–193. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsay M, Crino R, Andrews G. Controlled trial of exposure and response prevention in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:135–139. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Balkom AJ, de Haan E, van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin KA, van Dyck R. Cognitive and behavioral therapies alone versus in combination with fluvoxamine in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:492–499. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.March JS, Frances A, Carpenter D, Kahn DA. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997:58. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, Nestadt G, Simpson HB. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:5–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder (National Clinical Practice Guideline number CG31) London: British Psychological Society and Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goisman RM, Rogers MP, Steketee GS, Warshaw MG, Cuneo P, Keller MB. Utilization of behavioral methods in a multicenter anxiety disorders study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, Timpano KR, Jenike M, Wilhelm S. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:470–475. doi: 10.1002/da.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner SM, Beidel DC, Spaulding SA, Brown JM. The practice of behavior therapy: national survey of costs and methods. Behav Therapist. 1995;18:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davison GC. Being bolder with the Boulder model: the challenge of education and training in empirically supported treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:163–167. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crits-Christoph P, Chambless DL, Frank E, Brody C, Karp JF. Training in empirically validated treatments: What are clinical psychology students learning? Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1995;26:514–522. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritzler BK, Hecker JE, Losee MC. Self-directed treatment with minimal therapist contact: preliminary findings for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:627–631. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolin DF, Hannan S, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Worhunsky P, Brady RE. A randomized controlled trial of self-directed versus therapist-directed cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients with prior medication trials. Behav Ther. 2007;38:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagawa A, Marks IM, Park JM, et al. Self-treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder guided by manual and computer-conducted telephone interview. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6:22–26. doi: 10.1258/1357633001933899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean PD, Whittal ML, Thordarson DS, et al. Cognitive versus behavior therapy in the group treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto MW, Pollack MH, Maki KM. Empirically supported treatments for panic disorder: costs, benefits, and stepped care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:556–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison GC. Stepped care: doing more with less? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:580–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilliam CM, Diefenbach GJ, Whiting SE, Tolin DF. Stepped care for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolin DF, Diefenbach GJ, Maltby N, Hannan SE. Stepped care for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A pilot study. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005;12:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abramowitz JS, Foa EB, Franklin ME. Exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: effects of intensive versus twice-weekly sessions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:394–398. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren R, Thomas JC. Cognitive-behavior therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder in private practice: an effectiveness study. J Anxiety Disord. 2001;15:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guy W. Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for the classification of emotional disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arntz A, van Beijsterveldt B, Hoekstra R, Hofman A, Eussen M, Sallaerts S. The interrater reliability of a Dutch version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:394–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb10326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maffei C, Fossati A, Agostoni I, et al. Interrater reliability and internal consistency of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II), version 2. 0. J Personal Disord. 1997;11:279–284. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ekselius L, Lindstrom E, von Knorring L, Bodlund O, Kullgren G. SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90:120–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steketee G, Frost R, Bogart K. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: interview versus self-report. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holdnack J. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Sydney: The Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tolin DF, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Hannan SE, Worhunsky P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication nonresponders with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a wait-list-controlled open trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:922–931. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:299–313. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley MA, Beck JG, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatment of late-life GAD. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:309–319. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Revised 2007 Medicare Part B Physician and Nonphysician Practitioner Fee Schedule. Jacksonville, FL: First Coast Service Options, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Empolyment and Wages Summary, 2008. Washington, DC: United States Department of Labor; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foa EB, Wilson R. Stop Obsessing!: How to Overcome Your Obsessions and Compulsions. New York: Bantam Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D. Toward a standard definition of clinically significant change. Behav Ther. 1984;17:308–311. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGlinchey JB, Atkins DC, Jacobson NS. Clinical significance methods: which one to use and how useful are they? Behav Ther. 2002;33:529–550. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simpson HB, Huppert JD, Petkova E, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR. Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:269–276. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Mastery of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach (Therapist Guide) New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, Levitt JT, Foa EB. Effectiveness of exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized compared with nonrandomized samples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse of power: the pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat. 2001;55:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mark TL, Gibson TM, McGuigan K, Chu BC. The effects of antidepressant step therapy protocols on pharmaceutical and medical utilization and expenditures. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1202–1209. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09060877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]