Abstract

Cryptococcosis is a common opportunistic infection among immunocompromised individuals. Some of the commonly affected sites are respiratory and central nervous system. Lymph node is an unusual site of involvement which could mimic tuberculosis, as seen in our case. We report a 32-year-old male immunocompromised patient presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy who was clinically suspected to have tuberculous lymphadenitis. He was diagnosed to have disseminated cryptococcosis on fine needle aspiration cytology and fungal isolation on culture.

Keywords: Cryptococcosis, fine needle aspiration, immunocompromised, lymph node

Introduction

Cryptococcosis is a life-threatening opportunistic infection caused by the yeast like fungus, Cryptococcocus neoformans affecting both the immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.[1] Among the immunocompromised individuals, as seen in HIV patients, central nervous system and lungs are the commonly affected sites. Few of the unusual sites involved are optic nerve, bone, liver and lymph node.[2,3] We describe a case of disseminated cryptococcosis presenting as generalized lymphadenopathy, clinically mimicking tuberculous lymphadenitis, diagnosed on fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC).

Case Report

A 32-year-old male individual, an old treated case of tuberculous lymphadenitis presented to the medicine outpatient department with chief complaints of progressive breathlessness, weight loss and low-grade fever on and off for 3 months.

On examination, multiple bilateral cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes were present, the largest of them involving the axillary group measuring 3 × 2 cm. The lymph nodes were firm, non tender and discrete. Multiple pustular skin lesions were seen over the anterior abdominal wall. He also had hepatomegaly measuring 3 cm below the right costal margin. There was decreased air entry in the right lung base. A presumptive diagnosis of disseminated tuberculosis was made (probably relapse).

The blood film showed dual deficiency anemia, leukocytosis with toxic changes in neutrophils and thrombocytopenia. The liver function tests were normal. Renal parameters showed elevated (4.9 mg/dl) serum creatinine level. Chest radiograph showed miliary mottling and right pleural effusion suggestive of tuberculosis; ultrasonography of the abdomen showed hepatosplenomegaly and enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes. Serological workup for HIV was found to be reactive.

Cytological examination

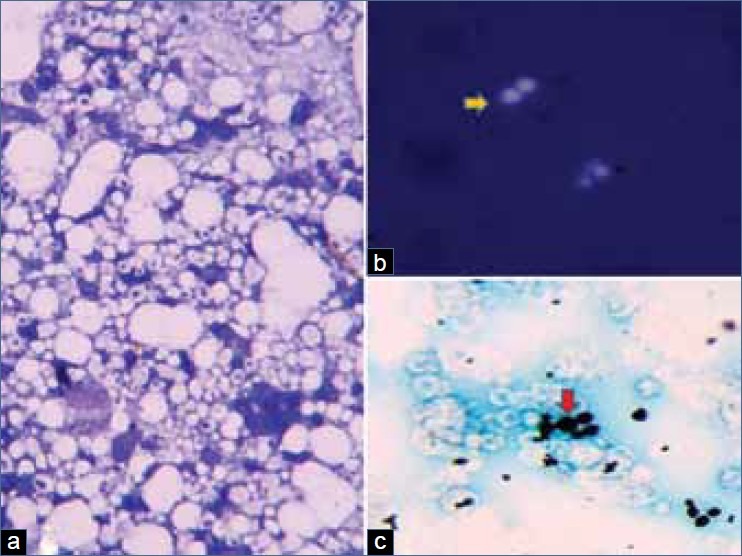

FNAC of the axillary and cervical lymph nodes were done. Routine examination with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (MGG) [Figure 1a] and hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stained smears demonstrated numerous spherical yeast cells of variable size with occasional budding forms surrounded by a clear halo suggestive of a capsule, lymphocytes and histiocytes in a necrotic background. No epithelioid cells were seen. No acid-fast bacilli were seen on Ziehl-Neelsen-stained smears. The possibility of cryptococcal infection was considered based on the above findings.

Figure 1.

(a) Numerous spherical yeast cells of variable size with occasional budding forms surrounded by a clear halo suggestive of a capsule, lymphocytes and histiocytes in a necrotic background (MGG, ×200).(b) Budding yeast forms surrounded by a thick capsule (yellow arrow) (India ink preparation, ×400). (c) Budding yeast forms (red arrow) of variable size surrounded by a clear halo (Gomori's methenamine silver, ×400)

Thick capsule was demonstrated on India ink preparation [Figure 1b] which was further highlighted by mucicarmine stain, imparting it a red color. Other special stains used to demonstrate the yeast forms were Periodic acid Schiff stain (PAS) and Gomori's silver methenamine stain [Figure 1c].

Cryptococcus was also demonstrated in the patient's skin lesions from skin scrapings and bone marrow aspiration including biopsy. The definitive diagnosis of C. neoformans was proven by isolating the fungus from the lymph node aspirate culture.

Discussion

Cryptococcosis caused by C. neoformans was first described in the 1890s though its increased prevalence was reported in the early 1980s owing to HIV pandemic, increased medical awareness and advanced diagnostic facility.[1] C.neoformans is considered an opportunistic infection as it affects mainly immunosuppressed individuals.

The first indigenous case of cryptococcosis was reported in Kolkata, India.[4] C. neoformans traditionally has two varieties. C. neoformans var. neoformans with serotypes A, D and AD; C. neoformans var. gattii with serotypes B and C. C. neoformans var. neoformans commonly affects immunocompromised hosts as in HIV patients while C. neoformans var. gatti is seen to affect mainly immuocompetent hosts.[1]

Cryptococcus is a fungus existing as yeast form, both in vitro and in vivo. The yeast cells show variable sized diameter ranging from 5 to 25 μ some of which show budding daughter yeast cells attached by a narrow base with a characteristic halo-like thick capsule made of polysaccharides.[5] The capsule is antiphagocytic and the capsular polysaccharide released in to the tissue initiates immune dysfunction. The cryptococcal polysaccharide is the antigen that is measured as the diagnostic marker of C. neoformans. The mode of spread is by inhalation of the aerosolized infectious particles. C. neoformans is frequently found in the soil contaminated with pigeon droppings.[1]

The differential diagnosis to be considered in an immunocompromised patient with generalized lymphadenopathy can be broadly divided in to non-neoplastic and neoplastic causes. The non-neoplastic entities include mainly infective etiologies and reactive hyperplasia (follicular). Infective etiologies include bacteria (tuberculosis), fungi (histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis), virus and parasites (toxoplasmosis). The neoplastic causes include lymphomas (Hodgkin's and Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma), Kaposi sarcoma and metastatic cancers.

FNAC of the largest lymph node is performed subjecting the aspirates to routine stains (MGG, H and E). Special stains for tuberculosis (Ziehl-Neelsen stain) and fungi (PAS and Gomori's silver methenamine stain) must be performed as and when indicated based on cytological findings. If the FNAC is inconclusive, excision biopsy of the lymph node is done. If cytological features of neoplastic etiology are demonstrated, excision biopsy of the lymph node must be performed for categorical diagnosis with use of supportive ancillary tests like immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry analysis and cytogenetics.

The diagnosis of cryptococcus is made by microscopically demonstrating yeast cells in tissue specimens like cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), sputum, lymph node aspirate and skin scrapings. The yeast cells are surrounded by a thick halo-like capsule demonstrated with India ink preparation and other special stains like Meyer's mucicarmine which imparts red color to the capsule. Other special stains used to demonstrate the yeast cells are PAS, Gomori's silver methenamine stain and alcian blue.[5]

The definitive diagnosis can be made by culturing the blood, CSF, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, urine and cytological aspirates. Cryptococcus grows best on fungal media such as Sabaraud's dextrose agar without cyclohexamide. Colonies appear within 2-5 days.[5]

Respiratory and central nervous system are two major sites of involvement. Several other organs including the skin, heart, testis, prostate and eye have also been affected by C.neoformans.[2,3,6]

Lymph node involvement in cryptococcosis is uncommon. There were three reported cases of disseminated cryptococcosis involving the lymph node proven on FNAC, of which two were immunocompromised.[7–9]

Banerjee et al.[10] in their review highlighted a case similar to ours that had presented with fever, weight loss and cervical lymphadenopathy and diagnosed as tuberculosis. The patient did not respond to antituberculous therapy. Lymph node biopsy revealed abundant C. neoformans cells which were supported by positive testing for cryptococcal antigen in the serum. Patient was seropositive for HIV.

To conclude, a high index of suspicion is needed to identify mimickers like cryptococcus which in our patient had initially presented as generalized lymphadenopathy. Early treatment could be started after diagnosis was established on FNAC.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson LJ, et al., editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2008. pp. 1251–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santosh V, Shankar SK, Das S, Pal L, Ravi V, Desai A, et al. Pathological lesions in HIV positive patients. Indian J Med Res. 1995;101:134–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakrabarti A, Verma SC, Roy P, Sakhuja V, Chander J, Prabhakar S, et al. Cryptococcosis in and around Chandigarh: an analysis of 65 cases. Indian J Med Microbiol. 1995;13:65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeves DL, Butt EM, Hammack RW. Torula infection of the lungs and central nervous system: Reports of six cases with three autopsies. Arch Intern Med. 1941;68:57–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giles TE, McCarthy J, Gray W. Respiratory tract. In: Gray W, Kocjan G, editors. Diagnostic cytopathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. pp. 17–111. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark RA, Greer D, Atkinson W, Valainis GT, Hyslop N. Spectrum of Cryptococcus neoformans infection in 68 patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:768–77. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shravanakumar BR, Iyengar KR, Parasappa Y, Ramprakash R. Cryptococcal lymphadenitis diagnosed by FNAC in a HIV positive individual. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Supparatpinyo K. Disseminated cryptococcosis rapidly diagnosed by lymph node imprint: A case report. J Infect Dis Antimicrob Agents. 1991;8:111–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suchitha S, Sheeladevi CS, Sunila R, Manjunath GV. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of cryptococcal lymphadenitis: A window of opportunity. J Cytol. 2008;25:147–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee U, Datta K, Majumdar, Gupta K. Cryptococcosis in India: the awakening of a giant? Med Mycol. 2001;39:51–67. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.1.51.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]