Abstract

Sinonasal malignant melanoma is of unusual occurrence. Common sites for melanomas are head, neck region, and the lower extremities as they are exposed to sunlight, which is one of the predisposing factors. We report a case of primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity in a 68-year-old male for its rare occurrence. The primary knowledge of its existence and evaluation of its cytological features are important for a correct preoperative cytological diagnosis and thereby clinical implications for appropriate therapeutic intervention. The cytological features when evaluated along with clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical features are sufficiently diagnostic. The rarity of its occurrence warrants its mention.

Keywords: Cytodiagnosis, mucosal melanoma, nasal cavity

Introduction

Melanomas are tumors arising from melanocytes, which are derived from neuroectoderm located in the basal layers of skin, skin annexes, and more rarely in the mucosal membrane. Common sites for melanomas are head, neck and the lower extremities, less common sites being the oral mucosa, nail beds, conjunctiva, orbit, esophagus, nasal mucosa or nasopharynx, vagina and leptomeninges. Sinonasal malignant melanoma is an extremely rare tumor, with primary mucosal melanoma being more aggressive than its cutaneous counterpart. It accounts for less than 1% of all western melanomas[1] and <5% of all sinonasal tract neoplasm. We report a case of primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity in a 68-year-old male for its rare occurrence.

Case Report

A 68-year-old male, farmer by occupation, presented with the complaints of nasal blockage and intermittent streaking of blood from left nostril for six months. There was no relevant past medical / family history. On examination, there was swelling of the left alar region. Anterior rhinoscopy showed a shiny polypoidal mass in the left nasal cavity which was friable and bled on touch. Patency was reduced and cavity was filled with blood stained discharge. Posterior rhinoscopy was normal. Examination of the throat, ears and larynx were normal. Evaluation of the case demonstrated only mild anemia with otherwise normal baseline hematological and biochemical profile. Urine and stool examinations were normal. Chest radiograph, ultrasonography of abdomen and all other relevant investigations were normal. Computed tomographic (CT) scan showed an enhancing soft tissue lesion in left nasal cavity with a suggestive diagnosis of a polypoidal mass not otherwise specified. CT guided aspiration cytology of the lesion was carried out. The smear showed large epithelioid and few spindle cells showing hyperchromatic nuclei, macronucleoli and both intra- and extra-cellular melanin pigments that led to a provisional diagnosis of malignant melanoma [Figure 1]. All other possible sites of primary malignant melanoma were excluded. The patient was operated and tumor was excised by lateral rhinotomy. The tumor was polypoidal and capsulated which ruptured during removal and hence it was removed in pieces. The tumor was attached with a broad base and was found on the inferior turbinate of left nasal cavity. After removal of tumor, the gross examination revealed several bits of blackish, irregular, soft and friable tissue, totally aggregating to form 5 cm × 6 cm mass. The hematoxylin and eosin stained section showed the tumor was composed of epithelioid and spindle cells which were medium to large in size, arranged in lobules and small bundles. The nuclei were pleomorphic, hyperchromatic with prominent nucleoli. Both extra and intracytoplasmic melanin pigment was noted [Figure 2]. Scattered mitoses and tumor giant cells were also seen. The overlying epithelium was ulcerated and only few intraepithelial atypical melanocytes noted. The case was diagnosed as primary mucosal malignant melanoma. HMB-45 and S-100 positivity further confirmed the diagnosis. Radiotherapy was given following complete wound healing. The patient is being followed up and till date there has been no recurrence.

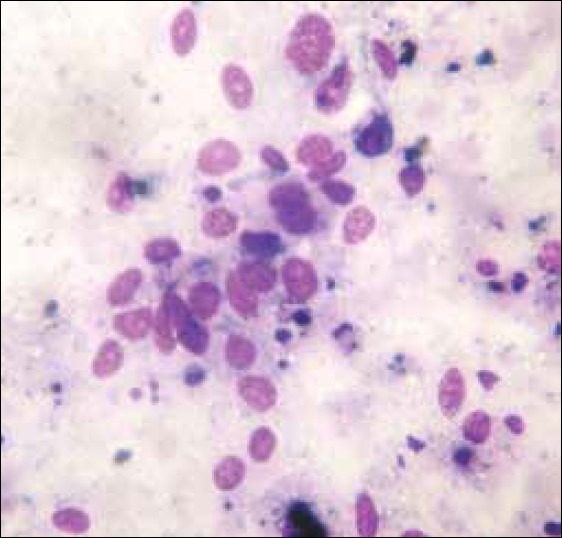

Figure 1.

The cytological smear showed large epithelioid and few spindle cells showing hyperchromatic nuclei, macronucleoli and both intra and extracellular melanin pigments (MGG, ×1000)

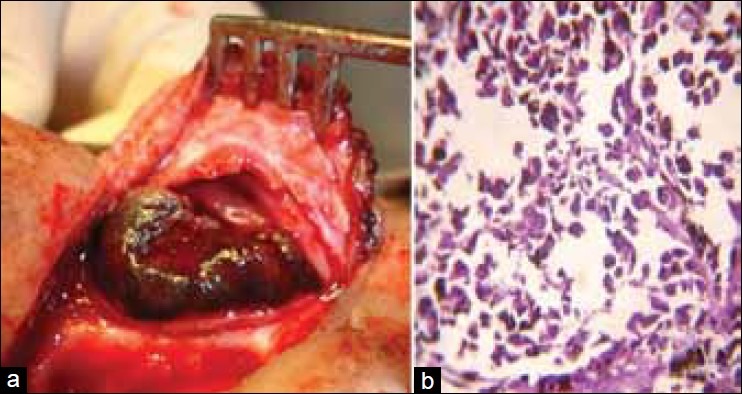

Figure 2.

(a) Intraoperative tumor-mass before resection. (b) Section showed medium to large size epithelioid and spindle cells arranged in lobules and small bundles with pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Both extra and intracytoplasmic melanin pigment was noted (H and E, ×400)

Discussion

Sinonasal malignant melanoma is an extremely rare tumor and more aggressive than its cutaneous counterpart. Lucke recognised it as a distinct clinical entity in 1869 on resecting a “melanotic sarcoma which arose from the nasal mucous membrane” from a man.[2] Melanocytes in the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract are the progenitors of the lesion. Formaldehyde exposure and tobacco smoking have been suggested as possible etiological factors.[2] They account for less than 1% of all melanomas and <5% of all sinonasal tract neoplasms. About 5% of nodular melanomas lack pigment (amelanotic melanoma). The tumor occurs between 50- 70 years of age, and both sexes are equally affected with no race predilection.

Patients with sinonasal mucosal malignant melanoma do not seem to be part of dysplastic nevus syndrome or xeroderma pigmentosum. Melanomas of the mucosal form are often diagnosed late due their hidden location and relatively nonspecific features.

The site most frequently involved in the nasal cavity is the nasal septum, and in our case the tumor originated from the inferior turbinate of the nasal cavity, which is one of the less common sites.

Malignant melanomas of the nasal cavities and sinuses are characterized by early and repeated recurrences. At presentation, 70-80% of cases are localized, 10-20% have regional lymph node, and <10% have distant metastasis. However, during the course of disease, an additional 20% may develop nodal metastasis and 40-50% may develop distant metastasis to lungs, brain, bone and/or liver.[3] Vascular and neural invasion is seen in 40% cases. However, in our case, the tumor was localized to the left nasal cavity.

There is currently no universally accepted staging system for mucosal melanoma. However, the most common and prognostically significant staging system in use is: stage I- localized tumors, stage II- tumors with lymph node metastasis, and stage III- tumors with distant metastasis.[3]

Tumor thickness or depth of invasion cannot be accurately assessed due to the lack of a well-defined reference point for the surface in the respiratory mucosa, frequent ulceration, tissue fragmentation and poorly oriented specimen.

Metastatic melanoma to the sinonasal tract, although highly uncommon, must always be excluded, as the prognosis is even poorer. Presence of intraepithelial atypical melanocytes favors primary neoplasm. The comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) profiles of sinonasal mucosal melanomas show remarkably consistent alterations: chromosome arm 1q is gained in all tumors and gains of 6p and 8q are present in 93 and 57%, respectively.[4]

Surgery is the cornerstone of therapy,[1,5] although wide free margins of resection are difficult to achieve. Local dose escalation with intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) yields good treatment results with respect to local and distant tumor control as well as survival, while treatment-related toxicity can be minimized.[6] Different chemotherapeutic regimens have been tried but all with unsatisfactory results. Local, regional recurrences and distant metastasis still occur despite the implementation of aggressive treatment, including surgery, radiation and adjuvant therapy.[7] Five-year survival rate is between 20 and 46%.[8] Other poor prognostic factors include: advanced age, obstructive symptoms, tumor size >3 cm, location in paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx, vascular invasion into skeletal muscle and bone, high mitotic count, marked cellular pleomorphism and distant metastasis.

Primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity is a rare, aggressive tumor with poor prognosis and late detection. So, early diagnosis with high index of suspicion is essential for the management of the condition.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, Hinerman RW, Werning JW, Villaret DB, Mendenhall NP. Head and neck mucosal melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:626–30. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000170805.14058.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manolidis S, Donald PJ. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: review of the literature and report of 14 patients. Cancer. 1997;80:1373–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1373::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenig BM, Dulguerov P, Kapadia SB, Prasad ML, Fanburg-Smith JC, Thompsonn LD. Tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: Neuroectodermal tumors. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization Classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 72–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Dijk M, Sprenger S, Rombout P, Marres H, Kaanders J, Jeuken J, et al. Distinct chromosomal aberrations in sinonasal mucosal melanoma as detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:151–8. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills SE. The Nose, paranasal sinuses, and nasopharynx. In: Mills SE, editor. Sternberg's diagnostic surgical pathology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. p. 881. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Combs SE, Konkel S, Thilmann C, Debus J, Schulz-Ertner D. Local high-dose radiotherapy and sparing of normal tissue using intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) for mucosal melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Strahlenther Onkol. 2007;183:63–8. doi: 10.1007/s00066-007-1616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean N, Tighiouart M, Muller S. Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Comparison of clinical presentation and histopathologic features of oral and sinonasal melanoma. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:1039–46. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liétin B, Montalban A, Louvrier C, Kemeny JL, Mom T, Gilain L. Sinonasal mucosal melanomas. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2010;127:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]