Abstract

Fixed drug eruption (FDE) is mainly characterized by skin lesions that recur at the same anatomic sites upon repeated exposures to an offending agent. It represents the most common cutaneous adverse drug reaction pattern in Indian patients. Here, we report an FDE to fluconazole.

KEY WORDS: Fixed drug eruption, cutaneous drug eruption, fluconazole

Introduction

Cutaneous drug eruption is the most common adverse drug reaction attributed to a drug. Fixed drug eruption (FDE) represents the most common cutaneous adverse drug reaction in Indian patients.[1] It is mainly characterized by skin lesions that recur at the same anatomic sites upon repeated exposures to an offending agent.[2] The drugs most commonly implicated in FDE are analgesics and antibiotics. We report an FDE occurring secondary to fluconazole intake.

Case Report

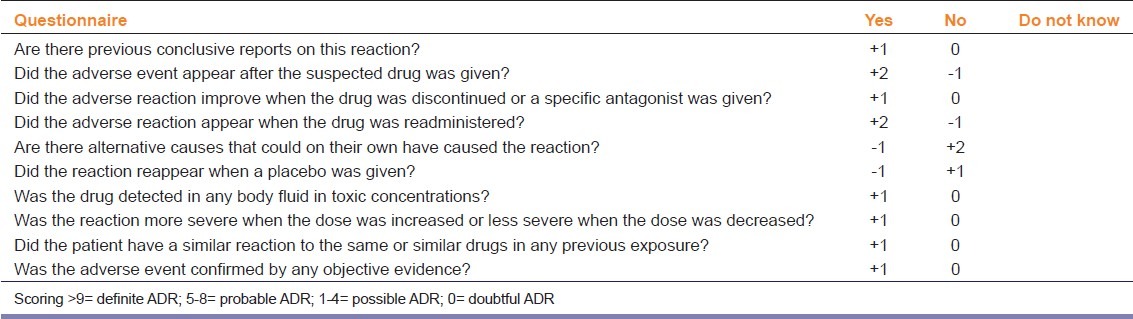

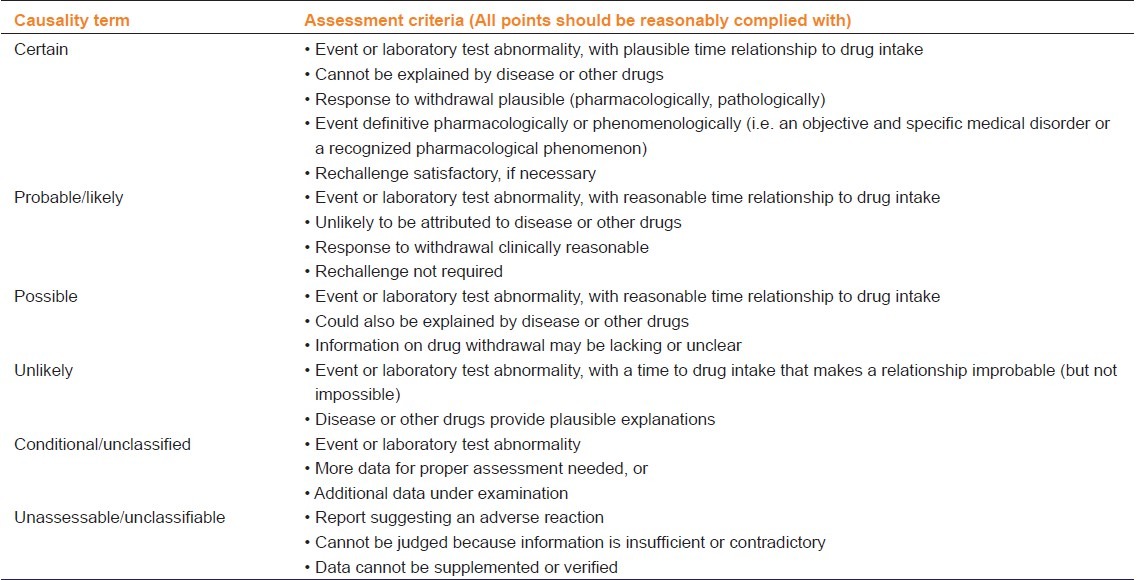

A 33-year-old male presented to the skin OPD with a history of rash since one day. The rashes were associated with burning and itching. History of drug intake (tab fluconazole 150 mg) for tinea cruris one day back at 9 pm was followed by itching with rash at 2 am at night. There was a history of similar lesions in the past due to some medication for a similar dermatological complaint. There was no history of fever or any medications. On cutaneous examination, well-defined erythematous plaques of varied sizes were present over the chest, back, lower limbs, and lips [Figure 1]. The largest over the chest was 10X10 cm. No involvement of the genitalia was present. A patch test done with the offending drug was positive. Complete blood count and biochemical investigations were normal. The causality assessment was carried out using the Naranjo ADR probability scale or WHO-UMC causality assessment scale [Tables 1 and 2]. A diagnosis of FDE to fluconazole was made and the patient was told to stop the offending agent and was started on oral antihistamines and topical steroids with complete recovery in five days.

Figure 1.

Violaceous plaque with erythematous border over the lower limb

Table 1.

Naranjo ADR probability scale

Table 2.

WHO-UMC causality assessment system

Discussion

FDE is a distinctive drug-induced dermatosis with a characteristic recurrence at the same sites of the skin or mucous membrane after repeated administration of the causative drug.[2] It was first described by Bourns in1889; five years later, it was termed by Brocq as “eruption erythemato-pigmentee fixe”.[3] FDE represents the most common cutaneous adverse drug reaction in the Indian scenario.[1] This adverse drug reaction seems to be more common in this part of the world, probably reflecting a predisposing genetic background.[4] FDE is believed to be a lymphocyte CD8-mediated reaction, wherein the offending drug may induce local reactivation of memory T cell lymphocytes localized in epidermal and dermal tissues and targeted initially by the viral infection.[5] The most common drugs causing FDE are antibiotics (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, penicillin, and erythromycin), followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; diclofenac sodium, aspirin, naproxen, and ibuprofen).[2]

FDE characteristically recurs in the same site or sites each time the drug is administered, and the number of sites may increase with subsequent exposure.[2] FDE presents mainly as sharply marginated, round or oval itchy plaques of erythema and edema becoming dusky violaceous or brown, and sometimes vesicular or bullous.[2] Most of the reactions occur within 30 minutes to one day of drug exposure.[2,4] The lesions may be solitary or multiple. The most common sites are the genitalia in males and the extremities in females.[4] Lesions can also be seen on the perianal, periorbital, and trunk.[2] They may be bullous, pigmented, or nonpigmented. Pigmented lesions can be seen in pigmented individuals and heroin addicts. Nonpigmented lesions are reported with pseudoephedrine use.[6]

Histologically, FDE is characterized by marked basal cell hydropic degeneration with pigmentary incontinence. Scattered keratinocyte necrosis with eosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nucleus (civatte bodies) are seen in the epidermis. Infiltration of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophil polymorphs is evident in the upper dermis.[7]

As most case reports concern suspected adverse drug reactions, pharmacovigilance can be problematic. Also, adverse reactions are rarely specific for the drug without specific diagnostic tests and a rechallenge is rarely ethically justified.[8] Therefore, certain causality assessment scales regarding drug reaction have been described like the Naranjo ADR probability scale or the WHO-UMC causality assessment system.[8,9] In our case, the association was ‘definite’ and ‘certain’ as per the Naranjo scale and WHO-UMC causality assessment system, respectively. For nonimmediate drug reactions like FDE, patch tests, together with delayed-reading intradermal tests, lymphocyte transformation tests (LTTs), and oral challenges can be used in selective cases.[10] Treatment includes stopping the offending drug with topical steroids, emollients, and oral antihistamines.[2]

Fluconazole is one of the most common drugs used in dermatology practice. It is a triazole which acts on lanosterol 14 α-demethylase and inhibits the conversion of lanosterol to ergosterol.[11] The adverse effects most frequently reported are nausea, headache, vomiting, and self-limiting biliary hepatitis.[11] The most common cutaneous adverse effect is skin rash. Severe cutaneous reactions like Stevens Johnson syndrome, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and erythema multiforme have been reported.[12] FDE to fluconazole is very rarely reported, with 13 cases reported till date.[13,14] Cross-reactions may occur with structurally related agents, such as itraconazole.[15]

Therefore, this case is presented for its rarity and also to create awareness about the various side effects associated with this very commonly prescribed medication.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Patel RM, Marfatia YS. Clinical study of cutaneous drug eruptions in 200 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2008;74:430. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.42883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breathnach SM. Drug reactions. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010. pp. 28–177. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brocq L. Éruptionerythemato-pigmentée fixe due al’antipyrine. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1894;5:308–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahimi N, Routier E, Raison-Peyron N, Tronquoy AF, Pouget-Jasson C, Amarger S, et al. A three-year-analysis of fixed drug eruptions in hospital settings in France. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:461–4. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: A disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201–8. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hindioglu U, Sahin S. Nonpigmenting solitary fixed drug eruption caused bypseudoephedrine hydrochloride. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:499–500. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70517-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiatt KM, Horn TD. Cutaneous toxicities of drugs. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, Xu X, editors. Levers histopathology of the skin. 10th ed. New Delhi: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 311–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The use of the WHO–UMC system for standardised case causality assessment. [Last accessed on 2012 May 12]. Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/graphics/24734.pdf .

- 9.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romano A, Viola M, Gaeta F, Rumi G, Maggioletti M. Patch testing in non-immediate drug eruptions. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4:66–74. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-4-2-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips MR, Rosen T. Topical antifungal agents. In: Wolverton SE, editor. Comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azón-Masoliver A, Vilaplana J. Fluconazole-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Dermatology. 1993;187:268–9. doi: 10.1159/000247261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan JM, Carmichael AJ. Fixed drug eruption with fluconazole. BMJ. 1994;308:454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6926.454a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beecker J, Colantonio S. Fixed drug eruption due to fluconazole. CMAJ. 2012;184:675. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R, Thami GP. Fixed drug eruption caused by itraconazole: Reactivity and cross reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:521–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]