Abstract

Background

Data regarding the association between HIV and DM are conflicting, with little known regarding the impact of including hemoglobin A1C (A1C) as a criterion for DM.

Methods

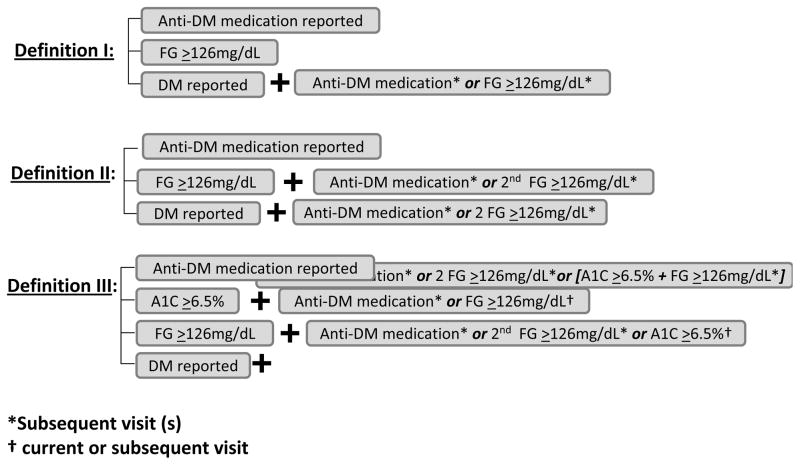

Pooled logistic regression was used to quantify the association between HIV and DM in 1501 HIV-infected and 550 HIV-uninfected participants from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Incident DM was defined using three DM definitions: (I) fasting glucose (FG) ≥126mg/dl, anti-DM medication, or reporting DM diagnosis (with confirmation by FG≥126mg/dl or anti-DM medication); (II) confirmation with a second FG≥126mg/dl; and (III) addition of A1C≥6.5% confirmed by FG≥126mg/dl or anti-DM medication.

Results

DM incidence per 100 person-years was 2.44, 1.55, and 1.70 for HIV-infected women; 1.89, 0.85, and 1.13 for HIV-uninfected women, using definition I, II, and III, respectively. After adjustment for traditional DM risk factors, HIV infection was associated with 1.23, 1.90, and 1.38-fold higher risk of incident DM, respectively; the association reached statistical significance only when confirmation with a second FG≥126mg/dl was required. Older age, obesity, and a family history of DM were each consistently and strongly associated with increased DM risk.

Conclusions

HIV infection is consistently associated with greater risk of DM. Inclusion of an elevated A1C to define DM increases the accuracy of the diagnosis and only slightly attenuates the magnitude of the association otherwise observed between HIV and DM. By contrast, a DM diagnosis made without any confirmatory criteria for FG ≥126mg/dl overestimates the incidence, while also underestimating the effects of HIV on DM risk, and should be avoided.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, HIV, Women, Hemoglobin A1C

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is of concern in the setting of HIV infection, given that both DM and HIV infection have been independently associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis [1–3]. Whether HIV infection is associated with an increased risk of DM is unclear. Conflicting findings have been identified in large cohort studies regarding the risk of DM in HIV-infected individuals relative to uninfected controls. Some studies have reported an association of HIV with a higher risk of incident DM [4, 5], while others have reported a similar [6, 7] or even lower risk [8] compared to those who are uninfected.

Possible explanations for these discrepant reports include the different ways in which DM was defined and the ability to control for factors associated with DM. Specifically, some definitions included a single fasting glucose (FG) measurement without confirmation [4, 5], while others required confirmation by an elevated random or FG measurement [7, 8].

In 2010, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) endorsed the recommendations of an International Expert Committee to include the presence of a hemoglobin A1C (A1C) measurement ≥6.5%, in addition to a confirmed elevated FG and/or random glucose measurement and use of anti-DM medication, as criteria for the definition of DM [9]. The inclusion of AIC should increase the accuracy of the DM diagnosis, because A1C is not impacted by fasting status and has less day-to-day variability than the glucose measurement.

To our knowledge, no published study has examined the impact of including A1C in the definition of DM in the setting of HIV infection. Using data collected prospectively from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a large representative cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected women in the United States, we examined the association of HIV and other factors with incident DM risk and compared how varying definitions of DM might affect these relationships.

METHODS

Study Population

The WIHS is a multicenter prospective cohort study that was established in 1994 to investigate the progression of HIV in women with and at risk for HIV infection. A total of 3766 women (2791 HIV-infected, 975 HIV-uninfected) were enrolled in either 1994–95 (n=2623) or 2001–02 (n=1,143) from six U.S. sites (Bronx, Brooklyn, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington DC). Baseline socio-demographic characteristics and HIV risk factors were similar between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women [10, 11]. An institutional review board approved study protocols and consent forms, and each study participant gave written informed consent.

Every six months, participants complete a comprehensive physical examination, provide biological specimens for CD4 cell count and HIV RNA determination, and complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire, which collects information on demographics, disease characteristics, and specific antiretroviral therapy (ARV) use.

Between October 2000 and March 2006, A1C and glucose were measured after participants had fasted for at least eight hours. Of the 2843 women with a visit between October 2000 and March 2006, 2538 had at least one visit with both FG and A1C measurements; the first visit with both FG and A1C data available will be referred to as the index visit. Sixty-two of these 2538 women were excluded due to either a positive (n=59) or missing (n=3) report of pregnancy at the index visit. Of the remaining 2476 women, 316 (221 of the 1797 HIV-infected, 95 of the 679 HIV-uninfected) were excluded from all analyses due to prevalent DM (defined as any of the following: a FG≥126mg/dL or A1C≥6.5% at index, anti-DM medication use reported prior to or at index, or a history of self-report DM prior to or at index). Of the remaining 2160 women, 109 had no follow-up with sufficient data to determine incident DM after the index visit, resulting in our final study population of 2051 women (1501 HIV-infected, 550 HIV-uninfected) who contributed a total of 14,821 visits of follow-up, including the index visit, to analyses. A1C and FG data were available at 11,633 (78%) and 9924 (67%) of these visits, respectively.

Ascertainment of Incident Diabetes Mellitus

Figure 1 outlines the criteria for the three different definitions of incident DM. Briefly, definition I uses the first report of anti-DM medication, a FG≥126mg/dL, or a report of DM with subsequent confirmation by either anti-DM medication use or FG≥126mg/dL, as previously used in WIHS [5]. Definition II differs from definition I in that an initial FG≥126mg/dL must be confirmed by a subsequent FG≥126mg/dL or report of anti-DM medication and a report of DM must be confirmed by a subsequent report of anti-DM medication or two FG measurements ≥126mg/dL. Definition III differs from definition II in that a confirmed A1C ≥6.5% is an additional criterion for DM. A report of DM must also be confirmed by a subsequent report of anti-DM medication, two FG≥126mg/dL, or FG≥126mg/dL concurrent with A1C≥6.5%. Because African American race has been associated with greater A1C levels relative to Caucasians [12], in definition III we required that an A1C≥6.5% be confirmed by a report of anti-DM medication or FG≥126 mg/dL as recommended by the ADA [9].

Figure 1.

First visit after index visit at which any of the following occur:

Exposures of Interest

In addition to the primary exposure of HIV status, we also examined the effect of race (Hispanic, Caucasian vs. African-American), HCV infection, and family history of DM on the risk of incident DM. We allowed age (35–<40, 40–<45, ≥45 vs. <35 yrs), current smoking status, menopause, and body mass index (25–<30, 30–<40, ≥40 vs. <25 kg/m2) to be time-varying, incorporating the value at the visit prior to ascertainment of DM in analyses.

We also examined the impact of ARV, CD4 cell count and HIV RNA on DM risk in HIV-specific analyses. The WIHS uses a standard definition of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adapted from the Department of Health and Human Services/Kaiser Panel guidelines [13]. All non-HAART combination therapy regimens were classified as combination therapy; reports of a single nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), protease inhibitor (PI), or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) were classified as monotherapy. ARV regimens were classified as no therapy, non-HAART ARV, PI-based HAART, and non-PI-based HAART and treated as time-varying exposures with ARV reported since the last visit at the visit of DM ascertainment used in analyses. CD4 cell count categorized as <200, 200–<350, 350–<500, and ≥500 cells/mm3 and HIV RNA categorized as <400, 400–<10,000, and ≥10,000 copies/ml were included in analyses as time-varying exposures using the value at the visit prior to ascertainment of DM.

Statistical Analyses

Person-years at risk for incident DM were calculated from the date of the index visit through either the date of DM (for those with incident DM) or the date of the last study visit (for those without incident DM). The crude incidence rates of DM for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women were calculated by dividing the number of incident DM cases by the total person-years at risk. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) for the crude incidence rates were obtained by standard methods based on the Poisson distribution [14]. Relative incidence rates and corresponding 95% CIs were obtained using Poisson Regression. Kappa statistics (κ) were used to quantify the pairwise agreement in the three incident DM definitions separately in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. Multivariate pooled logistic regression [15] was used to obtain odds ratios and 95% CIs to quantify the association that HIV status and the other primary exposures had with incident DM. Univariate odds ratios comparing HIV-infected women to HIV-uninfected women were very similar in value to the corresponding univariate relative incidence rates. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The demographic and clinical characteristics at the index visit of the 1501 HIV-infected and 550 HIV-uninfected women included in analyses are shown in Table 1. More than 50% of women were African-American. HIV-infected women were on average about five years older, more likely to be in menopause, and had slightly lower BMI than HIV-uninfected women. The prevalence of a family history of DM was similar in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. Smoking was reported in 47% of HIV-infected women and in 53% of HIV-uninfected women. The majority of HIV-infected women reported using ARV and had a CD4 count above 400cells/mm3.

Table 1.

Characteristics at the index visita

| Characteristic | HIV-infected (N=1501) | HIV-uninfected (N=550) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years [Median (IQR)] | 39 (33 – 45) | 35 (27 – 42) |

| Race [No. (%)] | ||

| African American | 839 (56%) | 318 (58%) |

| Hispanic | 425 (28%) | 152 (28%) |

| Caucasianb | 237 (16%) | 80 (15%) |

| Menopausalc [No. (%)] | 254 (17%) | 50 (9%) |

| Body Mass Indexc, kg/m2 [Median (IQR)] | 27 (23 – 31) | 28 (24 – 33) |

| Waist sizec, cm[Median (IQR)] | 87 (79 – 98) | 86 (77 – 99) |

| Hip sizec, cm [Median (IQR)] | 99 (91 – 108) | 102 (94 – 112) |

| Family history of diabetesc [No. (%)] | 437 (30%) | 141 (27%) |

| Current smoker [No. (%)] | 708 (47%) | 289 (53%) |

| Hepatitis C Virus RNA positivec [No. (%)] | 338 (23%) | 68 (13%) |

| Clinical AIDS [No. (%)] | 503 (34%) | NA |

| log10(HIV RNA)c, copies/ml [Median (IQR)] | 2.89 (1.90 – 4.04) | NA |

| CD4 countc, cells/mm3 [Median (IQR)] | 429 (266 – 622) | 967 (753, 1212) |

| nadir CD4 countc, cells/mm3 [Median (IQR)] | 256 (128 – 389) | 801 (632, 1044) |

| Antiretroviral therapy naïve [No. (%)] | 239 (16%) | NA |

IQR, inter-quartile range; NA, not applicable

If data were missing at index visit then data from visit closest to and prior to index visit (up to two visits prior to index visit) were used.

Includes 3.3% (n=50) and 4.5% (n=25) Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Alaskan, other among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women, respectively

Body Mass Index was missing on six HIV-infected and 2 HIV-uninfected women; Waist size was missing on 161 HIV-infected and 48 HIV-uninfected women; Hip size was missing on 162 HIV-infected and 49 HIV-uninfected women; Menopause status was missing on 3 HIV-infected women; Hepatitis C Virus RNA was missing on 32 HIV-infected and 13 HIV-uninfected women; Family history of diabetes was missing on 45 HIV-infected and 19 HIV-uninfected women; current HIV RNA was missing on 3 HIV-infected; current CD4 cell count was missing on 6 HIV-infected and 21 HIV-uninfected women; Nadir CD4 cell count was missing on 2 HIV-infected and 3 HIV-uninfected women

Table 2 shows the number of incident DM cases, the total person-years at risk for DM, and the crude incidence rate by HIV status for each of the three DM definitions. Relative to HIV-uninfected women, incidence rates of DM were higher among HIV-infected women for definitions I (2.44 per 100 person-years vs. 1.89 per 100 person-years; Relative Incidence 1.29, 95% CI: 0.88, 1.90) and III (1.70 per 100 person-years vs. 1.13 per 100 person-years; Relative Incidence 1.50, 95% CI: 0.92, 2.44), and were significantly higher with the biggest effect size when using definition II (1.55 per 100 person-years vs. 0.85 per 100 person-years; Relative Incidence 1.83, 95% CI: 1.05, 3.19).

Table 2.

Incidence Rates of Diabetes Mellitus for 1501 HIV-infected and 550 HIV-uninfected women

| No. (%) Incident DM cases | No. Person-Years | Crude Incidence Ratea (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition I | |||

| HIV-infected | 118 (7.9%) | 4836 | 2.44 (2.04, 2.92) |

| HIV-uninfected | 33 (6.0%) | 1745 | 1.89 (1.34, 2.67) |

| Definition II | |||

| HIV-infected | 76 (5.1%) | 4905 | 1.55 (1.24, 1.94) |

| HIV-uninfected | 15 (2.7%) | 1774 | 0.85 (0.51, 1.40) |

| Definition III | |||

| HIV-infected | 83 (5.5%) | 4886 | 1.70 (1.37, 2.11) |

| HIV-uninfected | 20 (3.6%) | 1765 | 1.13 (0.73, 1.76) |

per 100 person-years

Ninety-seven percent of both HIV-infected (= [1383 classified as not having DM + 76 classified as having DM]/1501) and HIV-uninfected (= [517 + 15]/550) women were classified the same way using all three definitions (Table 3). Among the HIV-infected women, the greatest agreement was observed between definitions II and III (κ = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92, 0.99), followed by definitions I and III (κ = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.75, 0.87) and definitions I and II (κ = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.70, 0.84). While the agreement in the three definitions among the 550 HIV-uninfected women was lower than the agreement in definitions among HIV-infected women, the pattern in the strength of pairwise agreement was similar. Specifically, definitions II and III had the greatest agreement (κ = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.73, 0.98), followed by definitions I and III (κ = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.61, 0.88) and definitions I and II (κ = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.45, 0.77).

Table 3.

Agreement in three definitions of incident diabetes mellitus

| 1501 HIV-infected women

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Times Positive | Definition I | Definition II | Definition III | % (n) |

| 0 | No | No | No | 92.1% (1383) |

|

| ||||

| 1 | Yes | No | No | 2.3% (35) |

| No | Yes | No | 0.0% (0) | |

| No | No | Yes | 0.0% (0) | |

|

| ||||

| 2 | Yes | Yes | No | 0.0% (0) |

| Yes | No | Yes | 0.5% (7) | |

| No | Yes | Yes | 0.0% (0) | |

|

| ||||

| 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5.1% (76) |

|

| ||||

| Total | 7.9% (118) | 5.1% (76) | 5.5% (83) | |

|

| ||||

| 550 HIV-uninfected women

| ||||

| Number of Times Positive | Definition I | Definition II | Definition III | % (n) |

|

| ||||

| 0 | No | No | No | 94.0% (517) |

|

| ||||

| 1 | Yes | No | No | 2.4% (13) |

| No | Yes | No | 0.0% (0) | |

| No | No | Yes | 0.0% (0) | |

|

| ||||

| 2 | Yes | Yes | No | 0.0% (0) |

| Yes | No | Yes | 0.9% (5) | |

| No | Yes | Yes | 0.0% (0) | |

|

| ||||

| 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2.7% (15) |

|

| ||||

| Total | 6.0% (33) | 2.7% (15) | 3.6% (20) | |

Table 4 shows the multivariate relationship between HIV status and incident DM after adjusting for demographic and traditional DM risk factors. The inferences are similar to the unadjusted relative incidence rates, namely HIV-infected women had a 1.90 (95% CI: 1.04, 3.48) fold higher DM risk using definition II. When using either definition I or III, the strength of the association between HIV infection and incident DM while positive was also weaker than the association seen with definition II. Because A1C levels are thought to be affected by mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and hemoglobin level, we further adjusted for these factors in the analysis using definition III and found little change in the estimates (data not shown). Among the traditional risk factors for DM, older age (≥45 vs. <35 years) was associated with a 3.37, 2.75, and 2.93-fold higher DM risk for definitions I, II, and III, respectively. We observed a consistently greater DM risk for each increase in BMI category relative to those who were normal weight (BMI<25kg/m2). Morbid obesity (BMI≥40kg/m2) was associated with a 3.76, 4.37, and 4.23-fold higher DM risk, respectively, followed by 2.60, 3.19, and 2.73-fold higher DM risk in those who were obese (BMI between 30 and <40kg/m2). Family history of DM was also consistently associated with DM risk. The association of HCV infection with increased DM risk only reached significance when using definition I.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Diabetes Mellitus Risk

| Definition I | Definition II | Definition III | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Characteristic | Odds Ratioa (95% CI) | Odds Ratiob (95% CI) | Odds Ratioc (95% CI) |

| HIV Status | |||

| Uninfected | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Infected | 1.23 (0.81, 1.87) | 1.90 (1.04, 3.48) | 1.38 (0.81, 2.35) |

| Age, years | |||

| <35 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 35 – <40 | 1.90 (1.04, 3.46) | 1.79 (0.86, 3.72) | 1.74 (0.85, 3.56) |

| 40 – <45 | 1.73 (0.94, 3.18) | 1.57 (0.74, 3.34) | 1.69 (0.82, 3.49) |

| ≥45 | 3.37 (1.86, 6.10) | 2.75 (1.30, 5.78) | 2.93 (1.44, 5.97) |

| Race | |||

| African American | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Hispanic | 1.28 (0.86, 1.90) | 0.98 (0.57, 1.67) | 1.23 (0.75, 2.01) |

| Caucasian | 1.29 (0.79, 2.09) | 1.54 (0.86, 2.76) | 1.70 (0.98, 2.96) |

| Menopause | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.96 (0.62, 1.48) | 1.11 (0.63, 1.94) | 1.25 (0.74, 2.12) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | |||

| <25 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 25 – <30 | 1.44 (0.89, 2.33) | 1.36 (0.71, 2.61) | 1.15 (0.62, 2.12) |

| 30 – <40 | 2.60 (1.65, 4.10) | 3.19 (1.77, 5.76) | 2.73 (1.57, 4.72) |

| ≥40 | 3.76 (2.09, 6.78) | 4.37 (2.08, 9.19) | 4.23 (2.13, 8.41) |

| Family History of Diabetes | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.48 (1.05, 2.10) | 1.69 (1.09, 2.61) | 1.86 (1.23, 2.81) |

| Currently Smoke Cigarettes | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.17 (0.82, 1.67) | 0.86 (0.55, 1.36) | 0.83 (0.53, 1.28) |

| HCV-infected | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.54 (1.03, 2.30) | 1.36 (0.80, 2.30) | 1.41 (0.86, 2.32) |

The 2051 women contributed a total of 12,225 visits after the index visit for the analysis of Definition I. Due to missing data 11,335 (93%) of these 12,225 visits were included in the analysis. Data were missing at the visit of incident diabetes mellitus in 12 (8%) of the 151 events.

The 2051 women contributed a total of 12,413 visits after the index visit for the analysis of Definition II. Due to missing data 11,506 (93%) of these 12,413 visits were included in the analysis. Data were missing at the visit of incident diabetes mellitus in 6 (7%) of the 91 events.

The 2051 women contributed a total of 12,362 visits after the index visit for the analysis of Definition III. Due to missing data 11,457 (93%) of these 12,362 visits were included in the analysis. Data were missing at the visit of incident diabetes mellitus in 9 (9%) of the 103 events.

Compared to HIV-infected women who reported no ARV, we found that a PI-containing HAART regimen was associated with a 2.17 (95% CI: 1.24, 3.82), 2.14 (95% CI: 1.06, 4.33), and 1.81 (95% CI: 0.92, 3.57)-fold higher DM risk using definition I, II, and III, respectively. Similarly, reported use of a non-PI-containing HAART regimen was associated with 2.06 (95% CI: 1.14, 3.71), 2.17 (95% CI: 1.05, 4.46), and 2.25 (95% CI: 1.14, 4.44)-fold higher DM risk, respectively. CD4 and HIV RNA were consistently not significantly associated with DM risk.

DISCUSSION

Using a large cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected women with similar risk behaviors, our study is the first to examine how DM definition (and specifically the inclusion of A1C criteria) impacts the association between HIV and DM risk after controlling for traditional DM risk factors. We made several noteworthy observations. DM incidence for HIV-infected and uninfected women was highest when confirmatory criterion for FG ≥126mg/dL in the definition of DM was not required, and the association of HIV with DM incidence weakest (1.2-fold higher compared to HIV-uninfected women). When confirmation of a single elevated FG level was required, HIV-infected women had a nearly 2-fold higher DM risk. When an elevated A1C level was included in the definition, we observed a smaller difference between HIV-infected and uninfected women, namely a 1.4-fold higher risk among HIV-infected women that changed little after further adjustment for MCV and hemoglobin level. Regardless of the DM definition used, traditional DM risk factors (older age, obesity, and family history of DM) were strongly associated with DM risk. Our findings suggest that the inclusion of A1C as a criterion for DM diagnosis increases the accuracy of the diagnosis and only slightly attenuates the magnitude of the association otherwise observed between HIV and DM. By contrast, a DM diagnosis made without any confirmatory criteria overestimates the incidence of DM, while also underestimating the association of HIV with DM risk, and should be avoided.

Whether or not HIV infection is associated with increased DM risk has been conflicting in published reports. One study reported a 4-fold higher DM risk in HIV-infected men on HAART compared to HIV-uninfected men [4]. That study did not use confirmatory data to define DM and did not control for risk factors such as family history of DM and HCV infection [4]. Subsequent studies have not found a strong association between HIV and DM risk. Among the large cohort studies that have used confirmatory criteria to define DM [7, 8], the Swiss Cohort Study (which defined DM by confirmation of elevated random or FG) observed similar age- and sex-specific incidence rates of DM between HIV-infected patients and a population-based cohort of HIV-uninfected patients [7]. The Veteran’s Administration Cohort Study (VACS) (which defined DM by confirmation of elevated random or FG or ICD-9 codes, indicating a diagnosis of DM plus either the use of anti-DM medication or elevated FG) found that HIV infection was associated with a 16% lower odds of prevalent DM [8]. In our large study that controlled for a number of traditional risk factors for DM, we found a consistent association between HIV infection and increased DM risk using all three definitions of incident DM. The association was strongest when confirmation of an elevated FG was required and weakest when an elevated FG was not confirmed.

While we found a greater DM incidence per 100 person-years in HIV-infected and uninfected women when an elevated A1C criteria was added to definition II, our finding that the association of HIV infection with DM risk was slightly attenuated when A1C criteria was included was not unexpected. Several studies have suggested that A1C (which is formed by the nonenzymatic attachment of glucose to hemoglobin over the life span of erythrocytes) may not accurately reflect glycemic control in HIV-infected persons with DM [16–19]. A study of WIHS women with DM found a slightly lower A1C value in those with HIV compared to those without HIV, which was explained primarily by the higher MCV in HIV-infected women [17]. That study postulated that the higher MCV may be a marker of a greater proportion of younger erythrocytes that have had a shorter time to become glycated because of greater red blood cell turnover. Similarly, anemia in the setting of hemolytic disease has been associated with spuriously low A1C values [20]. By contrast, African-Americans have been shown to have higher A1C values than Caucasians at similar glucose concentrations [12]. We minimized these effects in our study by requiring that an elevated A1C value be confirmed by a concurrent elevated FG or a report of anti-DM medication. We observed little change in the inferences regarding the association of Caucasian race (compared to African-Americans) with DM risk when A1C was included into the DM criteria. Finally, we also further adjusted for MCV and anemia in our study and found little change in the strength of the association between HIV and DM risk.

While we found that traditional risk factors such as older age, obesity, and family history of DM were strongly associated with incident DM risk regardless of the definition used, the association of HCV infection with DM was significant only when modeled using definition I. The association of HCV infection with DM in the HIV setting has been questioned in published reports. In the Swiss Cohort Study [7], HCV infection was associated with a 1.1-fold higher risk of incident DM in HIV-infected patients that was not statistically significant. The VACS study [8] found a 1.34-fold higher association of HCV infection with prevalent DM; when stratified by HIV status, the association remained significant in the HIV-infected group only. These findings as well as our own suggest an association of HCV with DM in the setting of HIV that is modest relative to the associations of traditional risk factors such as older age, obesity, and family history of DM.

When we examined the association of ARV with DM risk in HIV-infected women, we found those reporting HAART (PI or non-PI based) had greater DM risk compared to those reporting no ARV. These findings suggest that the effect of HAART on DM risk may be due to a general restoration of health or possibly a result of ARV drug class effects (e.g. PI, NNRTI, and/or nucleoside analogs. Prior studies in our cohort and others suggest an association of nucleoside analogs with incident DM [5] and insulin resistance [21–23]. Future investigation of the association of HIV infection with DM risk in the more recent HAART era (where thymidine analogs such as stavudine that have been associated with insulin resistance [21] and hyperinsulinemia [22]) are less frequently used) may be an important first step in determining whether the association of HIV infection with DM risk has been ameliorated.

The strengths of our study include the examination of incident DM using definitions consistent with prior and current ADA guidelines in a large cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected women with similar risk behaviors who underwent the same data collection procedures. One limitation of our study was that we were not able to discern whether anti-DM medications were taken to treat DM or for other reasons, such as to treat pre-DM or fat distribution changes associated with HIV. Furthermore, besides macrocytosis and anemia, there are a number of other factors, such as acute blood loss and chronic alcoholism that may impact A1C values, which we were not able to adjust for. Future studies should investigate other markers of glycemic control (e.g., fructosamine) not related to RBC survival. Finally, as with all observational studies, our findings are subject to possible unmeasured confounding.

We conclude that HIV infection is consistently associated with an increased risk of DM when examined using three definitions of incident DM. The association was strongest when confirmatory criteria for an elevated FG were required to define incident DM. Regardless of the DM definition used, traditional risk factors including older age, obesity, and family history of DM were strongly associated with incident DM risk. The inclusion of an elevated A1C level as a criterion for the diagnosis of DM can be used in the HIV setting. It increases the accuracy of the DM diagnosis and only slightly attenuates the association of HIV infection with DM risk. Future studies should examine how baseline A1C and/or baseline FG predicts DM (using a definition that includes confirmatory criteria for both FG≥126 mg/dL and A1C ≥6.5%) in the HIV setting.

Summary.

HIV infection is consistently associated with greater risk of DM. Inclusion of an elevated A1C to define DM can be used in the HIV setting. It may slightly underestimate the effects of HIV on DM risk.

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) located at: New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Analysis Center (Stephen Gange).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No authors report any financial arrangements relating to this manuscript.

The authors do not have an association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Financial disclosures: The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). Drs. Tien and Glesby are supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through R01 AI087176 and K24 AI078884, respectively. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Grunfeld C, Delaney JA, Wanke C, et al. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS (London, England) 2009 Sep 10;23(14):1841–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Gange SJ, et al. Low CD4+ T-cell count as a major atherosclerosis risk factor in HIV-infected women and men. AIDS (London, England) 2008 Aug 20;22(13):1615–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328300581d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007 Jul;92(7):2506–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Archives of internal medicine. 2005 May 23;165(10):1179–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cole SR, et al. Antiretroviral therapy exposure and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS (London, England) 2007 Aug 20;21(13):1739–45. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32827038d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brar I, Shuter J, Thomas A, Daniels E, Absalon J. A comparison of factors associated with prevalent diabetes mellitus among HIV-Infected antiretroviral-naive individuals versus individuals in the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey cohort. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2007 May 1;45(1):66–71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318031d7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Rickenbach M, et al. Factors associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected participants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jul 1;45(1):111–9. doi: 10.1086/518619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and the risk of diabetes mellitus. AIDS (London, England) 2009 Jun 19;23(10):1227–34. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832bd7af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ADA. Diagnosis and Classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33( 1S):S62–9S. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 2005 Sep;12(9):1013–9. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 1998 Mar;9(2):117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Weintraub WS, et al. Glucose-independent, black-white differences in hemoglobin A1c levels: a cross-sectional analysis of 2 studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Jun 15;152(12):770–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. US Department of Health and Human Services and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 1998. Panel on clinic practices for treatment of HIV infection. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvin S. Practical Biostatistical Methods. Belmont: Duxbury Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Agostino RB, Lee ML, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, Anderson K, Kannel WB. Relation of pooled logistic regression to time dependent Cox regression analysis: the Framingham Heart Study. Stat Med. 1990 Dec;9(12):1501–15. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780091214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diop ME, Bastard JP, Meunier N, et al. Inappropriately low glycated hemoglobin values and hemolysis in HIV-infected patients. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2006 Dec;22(12):1242–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glesby MJ, Hoover DR, Shi Q, et al. Glycated haemoglobin in diabetic women with and without HIV infection: data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Antiviral therapy. 2010;15(4):571–7. doi: 10.3851/IMP1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim PS, Woods C, Georgoff P, et al. A1C underestimates glycemia in HIV infection. Diabetes Care. 2009 Sep;32(9):1591–3. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polgreen PM, Putz D, Stapleton JT. Inaccurate glycosylated hemoglobin A1C measurements in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 2003 Aug 15;37(4):e53–6. doi: 10.1086/376633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bry L, Chen PC, Sacks DB. Effects of hemoglobin variants and chemically modified derivatives on assays for glycohemoglobin. Clinical chemistry. 2001 Feb;47(2):153–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cole SR, et al. Antiretroviral therapy exposure and insulin resistance in the Women’s Interagency HIV study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2008 Dec 1;49(4):369–76. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318189a780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown TT, Li X, Cole SR, et al. Cumulative exposure to nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors is associated with insulin resistance markers in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS (London, England) 2005 Sep 2;19(13):1375–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000181011.62385.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shlay JC, Bartsch G, Peng G, et al. Long-term body composition and metabolic changes in antiretroviral naive persons randomized to protease inhibitor-, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-, or protease inhibitor plus nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based strategy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2007 Apr 15;44(5):506–17. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31804216cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]