Summary

Biofilms are core to a range of biological processes, including the bioremediation of environmental contaminants. Within a biofilm population, cells with diverse genotypes and phenotypes coexist, suggesting that distinct metabolic pathways may be expressed based on the local environmental conditions in a biofilm. However, metabolic responses to local environmental conditions in a metabolically active biofilm interacting with environmental contaminants have never been quantitatively elucidated. In this study, we monitored the spatiotemporal metabolic responses of metabolically active Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms to U(VI) (uranyl, UO22+) and Cr(VI) (chromate, CrO42−) using noninvasive nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and spectroscopy (MRS) approaches to obtain insights into adaptation in biofilms during biofilm-contaminant interactions. While overall biomass distribution was not significantly altered upon exposure to U(VI) or Cr(VI), MRI and spatial mapping of the diffusion revealed localized changes in the water diffusion coefficients in the biofilms, suggesting significant contaminant-induced changes in structural or hydrodynamic properties during bioremediation. Finally, we quantitatively demonstrated that the metabolic responses of biofilms to contaminant exposure are spatially stratified, implying that adaptation in biofilms is custom-developed based on local microenvironments.

Introduction

In most natural, medical and engineered settings, microorganisms tend to grow as biofilms. A common feature that makes biofilms distinct from well-mixed planktonic cultures is spatial heterogeneity, in regard to both chemical gradients and microbial phenotypes. Gradients of nutrients, metabolites, and waste products may cause differential gene expression by cells in different regions in the biofilm structure, resulting in stratified metabolism and a variety of physicochemical microenvironments (Costerton et al., 1995; Yu and Bishop, 1998; Sternberg et al., 1999; Werner et al., 2004; Teal et al., 2006).

The heterogeneous microenvironments in biofilms have been demonstrated to have important biological consequences that help diversify the community to better resist external stresses (Boles et al., 2004; Pamp et al., 2008), yet limited information is available on the relationship between microenvironments and the differentiation of biofilm structure and metabolism. A comprehensive understanding of the relationship between microenvironments and biofilm differentiation will inform the engineering of biofilm-mediated processes for better performance. To this end, attempts have been made to quantify and spatially resolve physicochemical microenvironments and cellular metabolism in biofilms, primarily through the use of microsensors and microscopic techniques based on in situ responsive fluorophores. Microsensors have been extensively used to characterize physicochemical microenvironments (e.g., diffusion coefficients, pH, and dissolved O2 (DO)) in biofilms as well as to quantify O2 consumption and CO2 production as indicators of biofilm metabolism (Lewandowski et al., 1993; Rasmussen and Lewandowski, 1998; Yu and Bishop, 1998; Li and Bishop, 2004; Krawczyk-Barsch et al., 2008; Kroukamp and Wolfaardt, 2009; Bester et al., 2010). Another commonly used method for in situ measurements of physicochemical microenvironments and biofilm metabolism is chemical mapping based on fluorescence from fluorescent proteins expressed by cells, dyes or magnetic optical sensor particles that are introduced into biofilms (Wolfaardt et al., 1994; Nielsen et al., 2000; Werner et al., 2004; Teal et al., 2006; Saville et al., 2010; Fabricius-Dyg et al., 2012). In addition, microtoming has been coupled to microarray analysis to investigate the potential metabolic status of the inner and outer fractions of Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms on the anodes of microbial fuel cells (Franks et al., 2010). However, these methods require either physical contact with the biofilms during measurements or the use of genetically modified microorganisms, which makes the elucidation of real-time spatially resolved responses of intact metabolically active biofilms a primary challenge.

One promising noninvasive approach to monitoring intact biofilms is techniques based on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), including NMR imaging (MRI) and NMR spectroscopy (MRS). MRI has been used to measure mass transport, including the flow hydrodynamics and diffusion properties of metabolically active biofilms (Lewandowski et al., 1992; Lewandowski et al., 1993; Phoenix and Holmes, 2008; Renslow et al., 2010), while MRS can measure metabolite concentrations in metabolically active biofilms (Majors et al., 2005a; Majors et al., 2005b; McLean et al., 2008a; McLean et al., 2008b). Critically, MRI and MRS techniques do not require contrast agents, are noninvasive, and have a relatively fast response; thus, they provide an approach to monitoring the real-time responses of metabolically active biofilms. In this study, we applied spatially resolved MRI and MRS approaches and elucidated the spatiotemporal responses of metabolically active biofilms to environmental perturbations using Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 as a model organism and U(VI) (uranyl, UO22+) and Cr(VI) (chromate, CrO42−) as model environmental contaminants. The data reveal novel insights into the interactions between biofilms and environmental contaminants as evidenced by microscale variation in the diffusion coefficients of water and spatially stratified responses in the anaerobic metabolism of the cells in biofilms to the presence of U(VI) and Cr(VI). The findings suggest that adaptation in biofilms to contaminant exposure is developed based on local microenvironments.

Results and discussion

Biomass Distribution and Spatial Mapping of Water Diffusion Coefficients

We pre-grew S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilms on circular glass disks in a constant depth film fermenter (CDFF) and then transferred the biofilms to a custom-built NMR-compatible flow cell that was housed in the NMR magnet chamber to allow for further growth and NMR measurements. The physical structure of each biofilm sample in the NMR flow system was estimated using water-selective three-dimensional (3D) MRI techniques.

Spatially resolved biofilm structures a re important for monitoring biofilm development as well as for estimating biomass distribution over time. Microorganisms expressing fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP) in combination with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) are an effective noninvasive means for monitoring biofilm development over time (Lawrence et al., 1991; Davies et al., 1998). In the absence of microbially produced fluorophores, before CLSM can be applied, exogenous contrast agents, e.g., fluorescent dyes, must be introduced; this may perturb the biology and can provide only a snapshot of biofilm structure. In contrast, biofilm imaging using 3D MRI is based on signals of spin-lattice relaxation weighted to emphasize intra- and extracellular water in close association with the biofilm. Thus, it does not require external contrast agents to provide details of biomass distribution over time and it has no depth limitation for biofilm samples. A set of representative 2D and 3D MRI images of the biofilms is shown in Figure S1. Intensity, or brightness, in the images corresponds primarily to the volume fraction of water in that location. Through MRI imaging, we noninvasively obtained the biomass distribution before and after exposure to 126 μM U(VI) (~10 h) or 200 μM Cr(VI) (~6 h). The overall biomass distribution did not change noticeably with a total biovolume of ~3.16 mm3 (Figure S1), suggesting that S. oneidensis monoculture biofilms can maintain their structural integrity in the presence of these toxic contaminants.

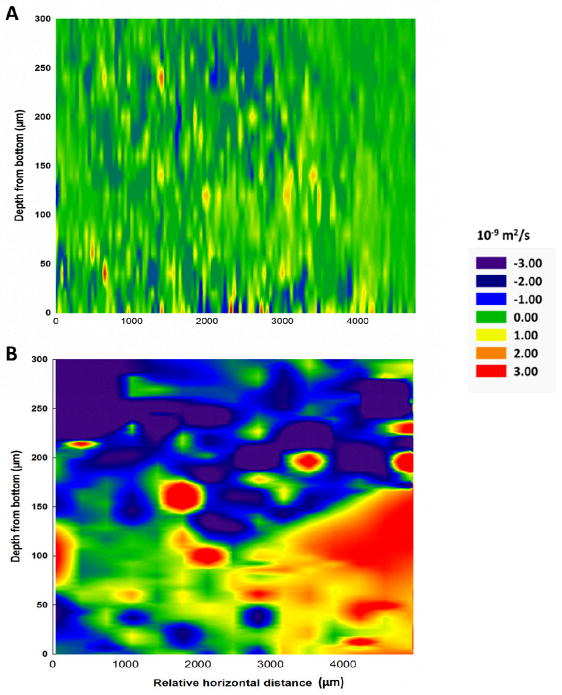

To further investigate whether the U(VI) or Cr(VI) exposure had microscale physicochemical influences on the biofilms, especially on the biofilm matrix, we spatially mapped the diffusion coefficients of water in the biofilms. Exposure to either U(VI) or Cr(VI) caused a decrease in the diffusion coefficients in the ~100-μm layer above the biofilm-bulk liquid interface, where loosely associated extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) can bind cations and change the structure and hydrodynamic properties of the polymers in EPS, resulting in a decrease in water diffusion (Cao et al., 2011a). The diffusion coefficients in the biofilm (overall average ~1.63±0.77 ×10−9 m2/s) before and after U(VI) or Cr(VI) exposure were statistically compared using a paired Student’s t-test (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Differences in the diffusion coefficients of water in two representative S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilms (~200 μm thick) caused by (A) uranyl exposure (p<0.05) or (B) chromate exposure (p<0.01). Statistical comparison was performed using a paired Student’s t-test. The difference maps were generated by subtracting the diffusion coefficients in the biofilms after exposure to U(VI) or Cr(VI) from those measured before exposure.

Exposure to either U(VI) or Cr(VI) caused significant changes in water diffusion in the biofilms, but the resulting patterns were markedly different. U(VI) exposure caused the development of discrete micro-zones with slightly decreased or increased diffusion coefficients (Fig. 1A). In contrast, Cr(VI) exposure resulted in horizontal channels up to 1500 μm long with dramatically altered diffusion coefficients and an overall increase in the diffusion coefficient in the base and near-base regions of the biofilm (Fig. 1B). Although the exact mechanism on how these diffusion patterns formed upon exposure to U(VI) and Cr(VI) remains unclear, at least two factors may have contributed to the difference in diffusion patterns observed: difference in toxicity of U(VI) and Cr(VI) to S. oneidensis MR-1 (Brown et al., 2006) as well as difference in physicochemical properties of their reductive products, i.e., U(IV) and Cr(III). Biofilms that are less dense at the bottom (increased diffusion coefficients) are more likely to detach (Bitton, 2005). The presence of high-diffusion horizontal channels at the base of the biofilm might be used to predict biofilm detachment upon chemical exposure.

Although MRI images showed that the overall biomass distribution was not significantly altered, MRI-based diffusion measurements showed localized changes in water diffusion coefficients in response to U(VI) or Cr(VI) exposure, which may represent a change in physicochemical microenvironments in the biofilm matrix. The primary reactive sites for U(VI) and Cr(VI) reduction in MR-1 are the c-type cytochromes at the outer membrane and in the matrix (Marshall et al., 2006; Belchik et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2011a). The reduction of U(VI) and Cr(VI) generates U(IV) and Cr(III) species that may further interact with polysaccharides in the biofilm matrix and cause changes in the structural configurations and hydrodynamic properties of the polymeric matrix (Kazy et al., 2008; Cetin et al., 2009). This may in turn alter the diffusion properties and hence the nutrient flux to the cells in the biofilm. In our recent work, we demonstrated the importance of the biofilm matrix in the bioremediation of toxic radionuclide contaminants by quantifying the direct contribution of EPS to U(VI) bioimmobilization (Cao et al., 2011b). Here, our results suggest that interactions between the biofilm matrix and U(VI) or Cr(VI) result in changes in diffusion properties, which may influence cellular nutrient acquisition and hence the metabolic activities of the biofilms. In addition to directly reducing and/or binding metal contaminants, EPS also interact with contaminants (Kazy et al., 2008; Cetin et al., 2009) to alter the diffusion properties of biofilms, which may be another important function of EPS affecting the fate of toxic contaminants during bioremediation processes. This finding led to the question: How would the metabolic activities in specific regions in the biofilms respond to contaminant-induced changes in their physicochemical microenvironments?

Spatiotemporal Metabolic Responses

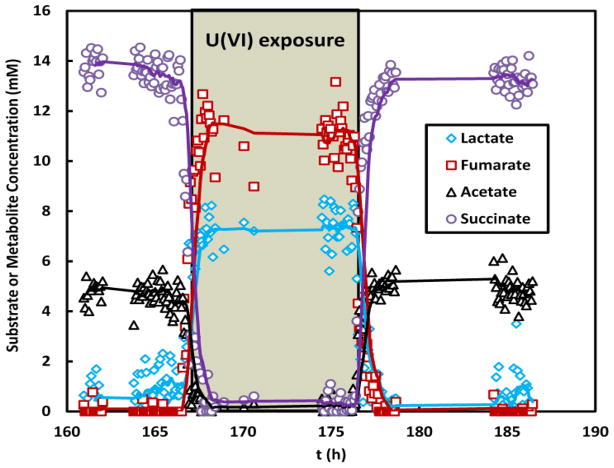

To obtain temporal metabolic profiles, averaged concentrations of metabolites in the flow cell were monitored before, during and after exposure using MRS (Fig. 2). Prior to U(VI) exposure, the electron donor (lactate) and electron acceptor (fumarate) were actively consumed with a significant accumulation of metabolic byproducts of their metabolism, acetate and succinate. Upon exposure to U(VI), lactate and fumarate consumption decreased sharply (within 1 h). At the same time, the generation of succinate and acetate nearly stopped. When the U(VI) was removed from the medium, metabolic activity within the biofilm recovered nearly completely within 1 h, as indicated by the resumed consumption of lactate and fumarate as well as the accumulation of succinate and acetate. Similarly, exposing metabolically active biofilm to Cr(VI) showed significant inhibitory effects on its metabolism (within 0.5 h), which recovered over a 2-h period following the removal of the Cr(VI) from the medium (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Temporal metabolic activities of a representative S. oneidensis biofilm in response to U(VI), from MRS measurements. The biofilm was loaded into the NMR flow system at t=0 and continuously fed with growth medium, with or without 126 μM UO2Cl2, at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/h.

Based on metabolite concentrations measured in quasi-steady states (i.e., with the concentration of the metabolite remaining approximately constant), we estimated the empirical stoichiometry of the anaerobic metabolism of lactate in S. oneidensis biofilms with fumarate as the electron acceptor (Table 1): this is the amount of acetate and succinate produced relative to the amount of lactate and fumarate consumed with a normalization to lactate.

Table 1.

Concentrations of lactate and fumarate as well as acetate and succinate in quasi-steady states in the absence or presence of U(VI) or Cr(VI)a. Standard deviations were calculated from all the data points measured in quasi-steady states.

| Mediumb | Metabolite concentration (mM) in quasi-stready states and empirical stoichiometry (in italics)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate | Fumarate | Acetate | Succinate | ||

| Biofilm 1c | No U(VI) | 0.82±0.66 | 0.05±0.15 | 4.69±0.46 | 13.54±0.61 |

| 1.00 lactate + 1.63 fumarate = 0.51 acetate + 1.47 succinate (succinate/fumarate = 0.90, acetate/lactate = 0.51) | |||||

|

| |||||

| With U(VI) | 6.91±0.68 | 10.51±1.32 | 0.38±0.30 | 1.21±1.07 | |

| 1.00 lactate + 1.45 fumarate = 0.12 acetate + 0.39 succinate (succinate/fumarate = 0.27, acetate/lactate = 0.12) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Biofilm 2c | No Cr(VI) | 1.27±0.95 | 1.21±0.82 | 3.83±0.51 | 12.56±0.88 |

| 1.00 lactate + 1.58 fumarate = 0.44 acetate + 1.44 succinate (succinate/fumarate = 0.91, acetate/lactate = 0.44) | |||||

|

| |||||

| With Cr(VI) | 7.57±0.98 | 12.17±0.56 | 0.08±0.12 | 0.86±0.62 | |

| 1.00 lactate + 1.16 fumarate = 0.03 acetate + 0.35 succinate (succinate/fumarate = 0.30, acetate/lactate = 0.03) | |||||

U(VI) (126 μM UO2Cl2) or Cr(VI) (200 μM K2CrO4) with a continuous medium flow at 0.5 ml/h;

the medium contained 10 mM lactate and 15 mM fumarate;

the S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilms used in the MRS measurements were about 100 μm thick, and the measurements were repeated at least twice for each set of conditions.

In the absence of U(VI) or Cr(VI), the stoichiometric ratios for the anaerobic respiration of fumarate with lactate in the biofilms (succinate/fumarate=0.90±0.01 and acetate/lactate=0.47±0.03) were slightly lower than those reported for planktonic cultures (succinate/fumarate=0.96±0.06 and acetate/lactate=0.63±0.02) (Tang et al., 2007a), which could be due to the diversion of lactate to extensive EPS production in biofilms. During exposure to U(VI) and Cr(VI), the lactate metabolism of the biofilms was inhibited significantly: the acetate/lactate stoichiometric ratios decreased 76% and 93% in the presence of U(VI) and Cr(VI), respectively. The more severe inhibitory effects of Cr(VI) could be due to the documented microbial toxicity of Cr(III) produced during Cr(VI) reduction (Bencheikh-Latmani et al., 2007; Belchik et al., 2011). In a recent study an incomplete reduction of 200 μM Cr(VI) was obtained in batch planktonic S. oneidensis cultures, which was also attributed to the toxic effects of Cr(III) (Belchik et al., 2011). In contrast, the reduction products of U(VI) are mainly nano-sized precipitates with minimal toxicity to the cells in biofilms (Marshall et al., 2006).

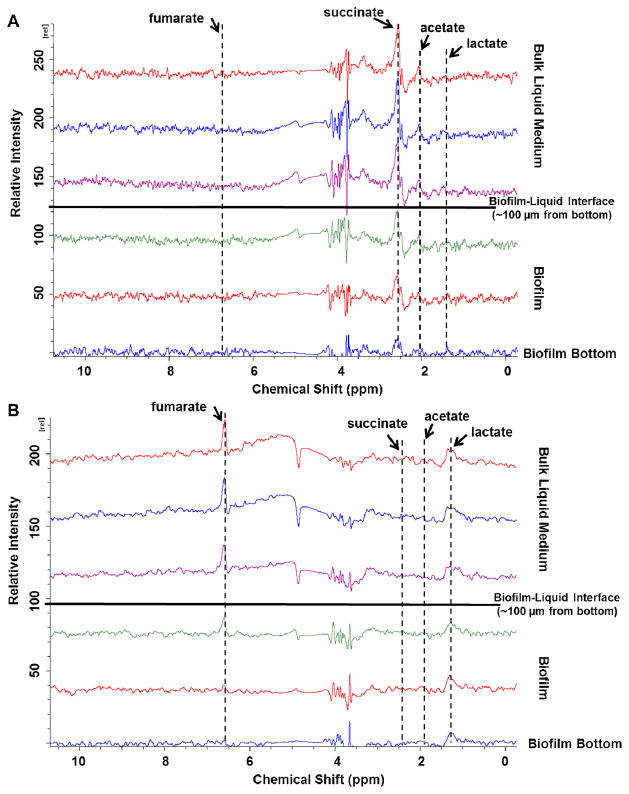

Because the changes in microenvironments upon U(VI) or Cr(VI) exposure varied with location, as indicated by diffusion coefficient mapping, we expected that the responses of metabolic activities within the biofilms would also vary spatially. To quantify spatially resolved metabolic activities in biofilms, concentration profiles of metabolites in metabolically active biofilms at different biofilm depths with a resolution of 30 μm (referred to as “depth-resolved” profiles) were obtained in the absence and presence of U(VI) (Fig. 3). The results indicate that before U(VI) exposure, although nearly all the lactate and fumarate in the chamber and the biofilm were consumed, lower stoichiometric ratios were observed at the bottom of the biofilm, suggesting a spatial stratification of cellular metabolic activity in the biofilms. The subpopulations at the top of the biofilm appeared to have higher respiratory activity than those at the bottom, which has also been suggested by McLean et al. (2008b).

Fig. 3.

Depth-resolved metabolism measurements of a representative S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilm (~100 μm thick) in the (A) absence or (B) presence of 126 μM UO2Cl2. The depth resolution was 30 μm. The top and the bottom of the biofilm are indicated.

In the presence of U(VI), neither succinate nor acetate was detected throughout the biofilm. Under anaerobic conditions, S. oneidensis MR-1 cells in planktonic culture couple lactate oxidation to acetate (~70%) with fumarate reduction, with the remaining lactate utilized in the gluconeogenesis and C1 metabolism pathways (Tang et al., 2007b). Our depth-resolved metabolic profiles show that, although the production of acetate in the biofilm was not observed, lactate continued to be consumed throughout the biofilm, with higher consumption rates towards the bottom of the biofilm, suggesting that at deeper strata in the biofilm more lactate may have been consumed through gluconeogenesis and C1 metabolic pathways, although the reasons for this remain unclear. One possible reason could be the need for carbon and energy sources for the enhanced production of EPS in response to a U(VI) challenge that has been suggested by previous studies (Marshall et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2011).

We then attempted to elucidate the depth-resolved metabolic responses of the biofilm to Cr(VI) exposure. A broad peak spanning the chemical shift range of 1.0–7.0 ppm was observed in the MRS spectra at various depths inside the biofilm; hence, the metabolites could not be unambiguously identified or quantified. We hypothesized that this “broadening effect” was due to a distortion of the magnetic field caused by paramagnetic soluble Cr(III) species (Cr(III)aq). We predicted that if this hypothesis was correct, a high concentration of Cr(III)aq would have accumulated in the biofilms. To test this prediction, local concentrations of Cr(III)aq within the biofilms were quantified.

Spatial Mapping Reveals High Local Concentrations of Cr(III)aq in Biofilms

The local concentrations of Cr(III)aq within metabolically active biofilms were measured using MRI-based T1 relaxation time mapping of 1H nuclei of water in the biofilms. C(VI) and Cr(OH)3(s) are diamagnetic and do not affect the T1 relaxation time constant (Beauregard et al., 2010), while C(III)aq is strongly paramagnetic, resulting in concentration-dependent T1 relaxation time constants. The inverses of T1 relaxation time constants are termed relaxation rates (R1=1/T1), and a linear relationship between R1 and Cr(III)aq can be established:

| Equation 1 |

where R1t is the inverse of the value of T1 that is measured using MRI, R1d is the diamagnetic contribution to the relaxation rate, R1Cr(III)aq is the concentration factor of the Cr(III)aq contribution to the relaxation rate, and [Cr(III)aq] is the concentration of Cr(III)aq. For solutions of Cr(III)aq (CrCl3(aq) in growth medium) in the NMR flow system, the values of R1d and R1Cr(III)aq were determined to be 0.36/s and 1.10/s/mM, respectively.

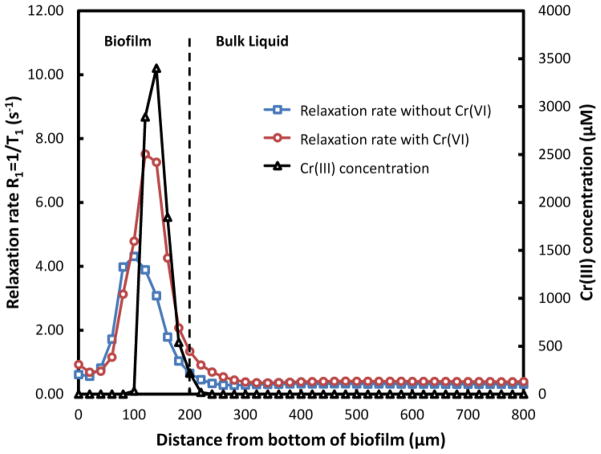

Fig. 4 shows the surface-averaged relaxation rate in the NMR flow cell and the depth-resolved Cr(III) concentration in a representative biofilm. Because Cr(VI) and Cr(III)(s) species are diamagnetic and do not affect relaxation, the changes in relaxation rate are attributed to Cr(III)aq. Based on Equation 1 with the predetermined parameters R1d and R1Cr(III)aq, the concentrations of Cr(III)aq at different depths were estimated and the resulting depth-resolved profile was determined. The local concentration of Cr(III)aq was very high (up to 2.5 mM) in the top ~100 μm of the biofilm, suggesting a relatively high Cr(VI) reduction activity in this region. The presence of a localized high concentration of Cr(III)aq in the biofilm is consistent with the hypothesized distortion of the magnetic field resulting in the broad peaks in the depth-resolved MRSI spectra.

Fig. 4.

Relaxation rate of water 1H nuclei in the NMR flow cell before and after exposure to 200 μM Cr(VI) for 6 h and the localized accumulation of Cr(III)aq in a representative S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilm (~200 μm thick) after the exposure.

The noninvasive monitoring of spatiotemporal responses of metabolically active S. oneidensis biofilms to exposure to U(VI) and Cr(VI) has provided novel insights into the interactions between biofilms and environmental contaminants. Our results suggest potentially important contaminant-induced changes in the structural or hydrodynamic properties of the biofilm matrix during the bioimmobilization of these metals. We also quantitatively demonstrate that the responses of cellular metabolism in biofilms interacting with environmental contaminants are spatially stratified, and our findings imply that adaptation in biofilms to contaminant exposure is custom-developed based on local microenvironments. The approaches used in this study can potentially be applied to investigate the spatiotemporal responses of biofilms noninvasively and will provide new avenues for elucidating interactions between biofilms and environmental contaminants, antimicrobials, or solid materials including electrodes.

Experimental procedures

Biofilm Cultivation

S. oneidensis MR-1 cells were grown with a modified formulation of chemically defined M1 medium (Zachara et al., 1998). The modified M1 medium (pH ~7.0) consisted of 3.00 mM PIPES, 7.50 mM NaOH, 26.04 mM NH4Cl, 1.34 mM KCl, 4.35 mM NaH2PO4 and 0.68 mM CaCl2 supplemented with trace amounts of minerals, vitamins, and amino acids (Cao et al., 2011a). Sodium lactate (10 mM) and sodium fumarate (15 mM) were added to the medium as an electron donor and an electron acceptor, respectively. S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilms were grown on 5-mm-diameter circular glass coverslips using a constant depth film fermenter (CDFF) (Peters and Wimpenny, 1988; Renslow et al., 2010). Detailed protocols for CDFF operation have been described elsewhere (Pratten, 2007). The CDFF was assembled and autoclaved, followed by the coverslips being rinsed with fresh growth medium. The modified M1 medium was then inoculated with approximately 50 ml of an overnight MR-1 seed culture (OD600 ~0.50) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min and a turntable rotation rate of 2 rpm. Upon inoculation, cells were allowed to attach for three hours with both the medium flow and the turntable rotation stopped. For biofilm growth, a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min was used to deliver growth medium and the turntable rotation rate was 3 rpm. The CDFF was operated at room temperature (20–25°C). The pressure within the CDFF was kept at equilibrium with atmospheric air through a 0.22-μm filter. Under these cultivation conditions, mature biofilms with a depth of 100–200 μm usually developed in 5–7 days.

NMR-Compatible Flow Cell for Biofilm Growth and Measurements

Biofilm studies were performed using a NMR-compatible flow cell (320-μl chamber volume) that is designed to support one 5-mm circular coverslip with a pre-grown biofilm (Renslow et al., 2010). Growth medium was delivered at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/h, which resulted in a laminar flow profile (McLean et al., 2008b; Renslow et al., 2010). The flow rates were controlled using a pulseless dual syringe pump (Pharmacia P-500, Uppsala, Sweden), and the flow cell temperature was maintained at 30±1°C by purging the magnet bore with N2 gas using a temperature-controlled gas stream delivery unit (FTS Systems, Stone Ridge, NY, USA). Previous investigations showed that, in the absence of an alternative electron acceptor, no acetate (from lactate oxidation) could be detected when air-saturated medium was used (McLean et al., 2008b), possibly because O2 was depleted near the top of the biofilm. Thus, the O2 concentration in this study was not controlled or measured. The biofilm was allowed to continue growing in the NMR chamber for 1–3 days before NMR spectra were collected. The exposure of biofilms to U(VI) or Cr(VI) was performed by switching to growth medium supplemented with 126 μM UO2Cl2 or 200 μM K2CrO4, respectively. The concentrations of U(VI) and Cr(VI) were chosen based on our previous work (Beyenal et al., 2004; Belchik et al., 2011). All the measurements carried out in this study were repeated at least twice using biofilm replicates from the CDFF.

NMR Configuration and Methods

All NMR measurements were performed at 500.44 MHz for protons (1H) using a Bruker Avance digital NMR spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA, USA) with an 11.7-T, 89-mm vertical bore, actively shielded superconducting magnet. ParaVision v5.1 imaging software (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA) was used to collect and process the data. Measurements included: 1) rapid multidirectional MRI to verify correct sample positioning and the absence of gas bubbles, 2) two-dimensional Fourier transform (2DFT) MRI, 3) three-dimensional Fourier transform (3DFT) MRI, 4) diffusion-mapping 2DFT MRI, 5) T1-mapping 2DFT MRI, 6) localized bulk MRS, and 7) depth-resolved MRS imaging (MRSI).

2D MRI

All 2DFT data employed field of view (FOV) dimensions of 10.24 mm by 5.12 mm. A total of 256 complex points were sampled at a rate of 100–200 Hz in the flow direction, with 256 phase-encoding (PE) steps in the biofilm-depth direction, for an in-plane resolution of 40 μm by 20 μm. The slice thickness was 2 mm, and Hermite 90-degree excitation pulses (10–12 kHz pulse bandwidth) and Gaussian 180-degree RF pulses (6–8 kHz RF pulse bandwidth) were employed.

Diffusion Measurements

The NMR signal intensity of protons (1H) is measured to determine the diffusion coefficients of water (Renslow et al., 2010). Diffusion mapping MRI provides images of biofilms weighted with the local microstructural characteristics of water diffusion. DtiStandard, a conventional diffusion measurement method in ParaVision, with a repetition time of 1500 ms, an echo time of 17.5 ms, and one average, was employed for diffusion mapping. The pulse gradient width (∂) was 3 ms, and the diffusion time interval (Δ) was 10 ms. The imaging sequence was repeated with seven different b-factors: 0–1200 s/mm2 in 200 s/mm2 increments aligned normal to the biofilm surface, for a total measurement time of 44.8 min. Two-dimensional diffusion maps were generated by processing the individual images (Gaussian noise filtering followed by fast 2DFT processing) and then performing a semilogarithmic analysis of the b-factor-dependent intensity value of each image pixel above a preset noise threshold.

T1 Relaxation Measurements

T1 experiments employed ParaVision’s saturation-recovery T1-mapping method (RAREVTR) with a variable repetition time of 3000, 300, 2000, 200, 1000 and 100 ms, an echo time of 11.4 ms, and two averages with a rapid acquisition with refocused echoes (RARE) factor of 2. The total measurement time was 28.2 min. Two-dimensional relaxation maps were generated by processing the individual images (Gaussian noise filtering followed by fast 2DFT processing) and then performing a semilogarithmic analysis of the T1-dependent intensity values using a saturation-recovery relaxation model.

3D MRI

3DFT MRI employed ParaVision’s RARE spin-echo method with a repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) of 500/10.3 ms. The field of view (FOV) was 10.24 mm × 5.12 mm × 5.12 mm, with 256 complex points sampled in the flow direction, a frequency resolution of 200 Hz, and 128 independently sampled PE steps in the two remaining directions, for an isotropic spatial resolution of 30 μm. The total measurement time was 2.25 h. Three-dimensional images were generated using Gaussian noise filtering and fast 3DFT processing.

Bulk MRS Measurements

Bulk MRS data were collected using the Bruker ParaVision point-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) method with a conventional water suppression scheme: variable pulse power and optimized relaxation delays (VAPOR). A total of 128 averages were collected with a TR/TE of 4000/10 ms, for a total measurement time of 8.8 min. A cubic volume with a length of 3 mm per side was centered on the coverslip, and a 90-degree Hermite RF excitation pulse (10 kHz pulse bandwidth) and two 180-degree Gaussian RF refocusing pulses (6-kHz pulse bandwidths) were employed. A total of 4096 complex data points were produced, with a spectral window of 7 kHz. The resulting water-suppressed NMR spectrum corresponds to a bulk metabolite spectrum of the biofilm and adjacent medium stream.

Depth-Resolved MRS Measurements

Depth-resolved MRSI profiles were collected using a gradient-echo 1D spectroscopic imaging method with VAPOR water suppression. Slice selection excitation was used to select a 3-mm-thick plane centered on the coverslip and normal to the flow direction. Depth profiling employed phase encoding in the direction normal to the coverslip with a FOV of 5.12 mm. For improved spatial localization, 189 PE steps were acquired with 2048 PE iterations and distributed over a Hanning function (a maximum of 20 PE averages were collected at the center of k space), then Fourier transformed to 128 points, yielding a spatial (biofilm depth) resolution of 40 μm. A TR of 2000 ms was employed, for a total measurement time of 68 min. A total of 4096 complex data points were sampled, with a spectral window of 7 kHz. VAPOR employed Hermite pulses with 500-Hz bandwidths. A second FT in the spectroscopic dimension yielded a two-dimensional data set with a spatial dimension (biofilm and chamber depth) and a water-suppressed 1H NMR spectral dimension corresponding to a depth-resolved metabolite map of the sample chamber and biofilm.

Data Analyses

Diffusion and T1 2D images were exported from ParaVision. The values at each pixel were extracted using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004) and analyzed using SigmaPlot (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Statistical comparison of diffusion images was performed using a paired Student’s t-test. Surface-averaged T1 relaxation rates were obtained by averaging the relaxation rates for each row of pixels. NMR spectra were processed using Bruker TopSpin processing software for exponential multiplication, Fourier transformation and first-order phase correction. The baseline was adjusted using a cubic spline fitting procedure, and the individual peaks were integrated (TopSpin) and exported to Excel. Metabolite concentrations were derived by calibration of the spectral signal intensities with the non-suppressed MRS measurements of water in the medium with an assumed concentration of 55 M. Metabolically invariant 3 mM PIPES buffer peaks in the range of 2.72 ppm and 3.38 ppm were used for an internal concentration reference.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research under the Subsurface Biogeochemistry Research (SBR) Program (grant DE-FG92-08ER64560), the DOE-BER SBR Program’s Scientific Focus Area (SFA) at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), and NIEHS/NIH (grant 21R01ES017070-01). A portion of the research was performed in the William R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the DOE’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at PNNL. PNNL is operated by Battelle for the DOE under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830.

References

- Abramoff M, Magelhaes P, Ram S. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard D, Yong P, Macaskie L, Johns M. Using non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the reduction of Cr(VI) using a biofilm-palladium catalyst. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2010;107:11–20. doi: 10.1002/bit.22791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belchik SM, Kennedy DW, Dohnalkova AC, Wang YM, Sevinc PC, Wu H, et al. Extracellular Reduction of Hexavalent Chromium by Cytochromes MtrC and OmcA of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77:4035–4041. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02463-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencheikh-Latmani R, Obraztsova A, Mackey MR, Ellisman MH, Tebo BM. Toxicity of Cr(III) to Shewanella sp. strain MR-4 during Cr(VI) reduction. Environmental Science & Technology. 2007;41:214–220. doi: 10.1021/es0622655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester E, Kroukamp O, Wolfaardt G, Boonzaaier L, Liss S. Metabolic differentiation in biofilms as indicated by carbon dioxide production rates. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76:1189–1197. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01719-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyenal H, Sani R, Peyton B, Dohnalkova A, Amonette J, Lewandowski Z. Uranium immobilization by sulfate-reducing biofilms. Environmental Science & Technology. 2004;38:2067–2074. doi: 10.1021/es0348703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitton G. Wastewater Microbiology. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boles B, Thoendel M, Singh P. Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:16630–16635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407460101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Thompson MR, Verberkmoes NC, Chourey K, Shah M, Zhou J, et al. Molecular dynamics of the Shewanella oneidensis response to chromate stress. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2006;5:1054–1071. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500394-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B, Shi L, Brown RN, Xiong YJ, Fredrickson JK, Romine MF, et al. Extracellular polymeric substances from Shewanella sp. HRCR-1 biofilms: characterization by infrared spectroscopy and proteomics. Environmental Microbiology. 2011a;13:1018–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B, Ahmed B, Kennedy DW, Wang ZM, Shi L, Marshall MJ, et al. Contribution of Extracellular Polymeric Substances from Shewanella sp. HRCR-1 Biofilms to U(VI) Immobilization. Environmental Science & Technology. 2011b;45:5483–5490. doi: 10.1021/es200095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin Z, Kantar C, Alpaslan M. Interactions between Uronic Acids and Chromium(III) Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2009;28:1599–1608. doi: 10.1897/08-654.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell D, Korber D, Lappin-Scott H. Microbial biofilms. Annual Review in Microbiology. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D, Parsek M, Pearson J, Iglewski B, Costerton J, Greenberg E. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius-Dyg J, Mistberger G, Staal M, Borisov S, Klimant I, Kuhl M. Imaging of surface O2 dynamics in corals with magnetic micro optode particle. Marine Biology. 2012 In press. [Google Scholar]

- Franks A, Nevin K, Glaven R, Lovley D. Microtoming coupled to microarray analysis to evaluate the spatial metabolic status of Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms. The ISME Journal. 2010;4:509–519. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Kim MG, Kim SJ, Suk H, Lee S, Noh D, et al. Bacterial formation of extracellular U(VI) nanowires. Chem Commun. 2011;47:8076–8078. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12554k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazy S, Sar P, D’Souza S. Studies on uranium removal by the extracellular polysaccharide of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain. Bioremediation Journal. 2008;12:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk-Barsch E, Grossmann K, Arnold T, Hofmann S, Wobus A. Influence of uranium(VI) on the metabolic activity of stable multispecies biofilms studied by oxygen microsensors and fluorescence microscopy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2008;72:5251–5265. [Google Scholar]

- Kroukamp O, Wolfaardt G. CO2 production as an indicator of biofilm metabolism. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75:4391–4397. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01567-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JR, Korber DR, Hoyle BD, Costerton JW, Caldwell DE. Optical Sectioning of Microbial Biofilms. Journal of Bacteriology. 1991;173:6558–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6558-6567.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski Z, Altobelli S, Fukushima E. NMR and microelectrode studies of hydrodynamics and kinetics in biofilms. Biotechnology Progress. 1993;9:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski Z, Altobelli S, Majors P, Fukushima E. NMR imaging of hydrodynamics near microbially conlonized surfaces. Water Science and Technology. 1992;26:577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Bishop P. Time course observation of nitrifying biofilm development using microelectrodes. Journal of Environmental Engineering and Science. 2004;3:523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Majors PD, McLean JS, Fredrickson JK, Wind RA. NMR methods for in-situ biofilm metabolism studies: spatial and temporal resolved measurements. Water Science and Technology. 2005a;52:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majors PD, McLean JS, Pinchuk GE, Fredrickson JK, Gorby YA, Minard KR, Wind RA. NMR methods for in situ biofilm metabolism studies. J Microbiol Methods. 2005b;62:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M, Beliaev A, Dohnalkova A, Kennedy D, Shi L, Wang Z, et al. c-Type cytochrome-dependent formation of U(IV) nanoparticles by Shewanella oneidensis. PLos Biology. 2006;4:1324–1333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J, Ona O, Majors P. Correlated biofilm imaging, transport and metabolism measurements via combined nuclear magnetic resonance and confocal microscopy. The ISME Journal. 2008a;2:121–131. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JS, Majors PD, Reardon CL, Bilskis CL, Reed SB, Romine MF, Fredrickson JK. Investigations of structure and metabolism within Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms. J Microbiol Methods. 2008b;74:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen AT, Tolker-Nielsen T, Barken KB, Molin S. Role of commensal relationships on the spatial structure of a surface-attached microbial consortium. Environmental Microbiology. 2000;2:59–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamp SJ, Gjermansen M, Johansen HK, Tolker-Nielsen T. Tolerance to the antimicrobial peptide colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is linked to metabolically active cells, and depends on the pmr and mexAB-oprM genes. Molecular Microbiology. 2008;68:223–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AC, Wimpenny JWT. A constant-depth laboratory model film fermentor. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1988;32:263–270. doi: 10.1002/bit.260320302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix V, Holmes W. Magnetic resonance imaging of structure, diffusivity, and copper immobilization in a phototrophic biofilm. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74:4934–4943. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02783-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratten J. Growing Oral Biofilms in a Constant Depth Film Fermenter (CDFF) Current Protocols in Microbiology. 2007;6:1B.5.1–1B.5.18. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b05s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Lewandowski Z. Microelectrode measurements of local mass transport rates in heterogeneous biofilms. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1998;59:302–309. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980805)59:3<302::aid-bit6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renslow RS, Majors PD, McLean JS, Fredrickson JK, Ahmed B, Beyenal H. In situ effective diffusion coefficient profiles in live biofilms using pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106:928–937. doi: 10.1002/bit.22755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saville R, Dieckmann N, Spormann A. Spatiotemporal activity of the mshA gene system in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2010;308:76–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg C, Christensen BB, Johansen T, Nielsen AT, Andersen JB, Givskov M, Molin S. Distribution of bacterial growth activity in flow-chamber biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1999;65:4108–4117. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.4108-4117.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YJ, Meadows AL, Kirby J, Keasling JD. Anaerobic central metabolic pathways in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 reinterpreted in the light of isotopic metabolite labeling. J Bacteriol. 2007a;189:894–901. doi: 10.1128/JB.00926-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YJ, Hwang JS, Wemmer DE, Keasling JD. Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 fluxome under various oxygen conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007b;73:718–729. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01532-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teal T, Lies D, Wold B, Newman D. Spatiometabolic stratification of Shewanella oneidensis biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:7324–7330. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01163-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Roe F, Bugnicourt A, Franklin M, Heydorn A, Molin S, et al. Stratified growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70:6188–6196. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6188-6196.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfaardt GM, Lawrence JR, Robarts RD, Caldwell SJ, Caldwell DE. Multicellular Organization in a Degradative Biofilm Community. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1994;60:434–446. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.434-446.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Bishop P. Stratification of microbial metabolic processes and redox potential change in an aerobic biofilm studied using microelectrodes. Water Science and Technology. 1998;37:195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zachara J, Fredrickson J, Li S, Kennedy D, Smith S, Gassman P. Bacterial reduction of crystalline Fe3+ oxides in single phase suspensions and subsurface materials. American Mineralogist. 1998;88:1426–1443. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.