Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Although 5-HT1B receptors are expressed in trigeminal sensory neurons, it is still not known whether these receptors can modulate nociceptive transmission from primary afferents onto medullary dorsal horn neurons.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Primary afferent-evoked EPSCs were recorded from medullary dorsal horn neurons of rat horizontal brain stem slices using a conventional whole-cell patch clamp technique under a voltage-clamp condition.

KEY RESULTS

CP93129, a selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist, reversibly and concentration-dependently decreased the amplitude of glutamatergic EPSCs and increased the paired-pulse ratio. In addition, CP93129 reduced the frequency of spontaneous miniature EPSCs without affecting the current amplitude. The CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was significantly occluded by GR55562, a 5-HT1B/1D receptor antagonist, but not LY310762, a 5-HT1D receptor antagonist. Sumatriptan, an anti-migraine drug, also decreased EPSC amplitude, and this effect was partially blocked by either GR55562 or LY310762. On the other hand, primary afferent-evoked EPSCs were mediated by the Ca2+ influx passing through both presynaptic N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. The CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was significantly occluded by ω-conotoxin GVIA, an N-type Ca2+ channel blocker.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The present results suggest that the activation of presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors reduces glutamate release from primary afferent terminals onto medullary dorsal horn neurons, and that 5-HT1B receptors could be, at the very least, a potential target for the treatment of pain from orofacial tissues.

LINKED ARTICLE

This article is commented on by Connor, pp. 353–355 of this issue. To view this commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01963.x

Keywords: serotonin, 5-HT1B receptors, trigeminal nucleus, EPSCs, presynaptic inhibition, pain

Introduction

Neurons within the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (Vc) receive primary afferent Aδ- and C-fibres from orofacial tissues and process orofacial nociceptive transmission, including migraine (Jacquin et al., 1986; Ambalavanar and Morris, 1992; Crissman et al., 1996). Among them, substantia gelatinosa (SG, or lamina II) neurons also receive these afferent fibres and project their axon terminals to the SG and adjacent laminae (Li et al., 1999), suggesting that changes in the excitability of SG neurons via primary afferents as well as local interneurons play crucial roles in the processing of pain signals (Furue et al., 2004). Nociceptive transmission can also be regulated by descending inhibitory pathways, which are mediated by descending noradrenergic and 5-hydroxytryptaminergic projections from the brain stem to spinal or medullary dorsal horn areas (Sandkühler, 1996; Millan, 2002). For example, the intrathecal administration of either hydroxytryptaminergic or noradrenergic agents induces anti-nociceptive actions (Yaksh and Wilson, 1979; Reddy and Yaksh, 1980; DeLander and Hopkins, 1987; Obata et al., 2004). In addition, either NA or 5-HT hyperpolarizes SG neurons (Grudt et al., 1995) and inhibits glutamatergic excitatory transmission onto SG neurons in the Vc (Travagli and Williams, 1996).

5-HT acts on 5-HT receptors to exert a variety of pathophysiological functions, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, aggression and migraine, in the CNS (for review, see Lucki, 1998). Most 5-HT receptors, except 5-HT3 receptors, belong to the GPCR superfamily and, with at least fourteen distinct members, represent one of the most complex families of neurotransmitter receptors (Hoyer et al., 1994; Barnes and Sharp, 1999). Of them, the 5-HT1 receptor subtype, such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E and 5-HT1F receptors, is widely distributed in the CNS. They are expressed on the neuronal membrane, including presynaptic terminals, and regulate neuronal excitability via either the direct hyperpolarization of postsynaptic neurons or the presynaptic modulation of neurotransmitter release (Barnes and Sharp, 1999; Fink and Göthert, 2007; Feuerstein, 2008). 5-HT1 receptors are known to modulate transmission of noxious sensory information in the orofacial region (Deseure et al., 2002; Kayser et al., 2002; Okamoto et al., 2005). Among them, 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors are expressed on sensory neurons such as dorsal root ganglia (Nicholson et al., 2003; Classey et al., 2010), suggesting that 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors are involved in the modulation of pain information from peripheral tissues. Similarly, a recent study has shown that i.t. administration of sumatriptan, which is used for the treatment of migraine and activates 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors (Tepper et al., 2002; Ahn and Basbaum, 2005), profoundly reduces somatic and visceral pain (Nikai et al., 2008). On the other hand, 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors are also expressed on trigeminal ganglia (TG) (Hou et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2001). Although a previous study has shown that 5-HT1D receptors inhibit glutamate release onto SG neurons of the Vc (Jennings et al., 2004), it is still not known whether 5-HT1B receptors can modulate glutamatergic transmission. In the present study, therefore, we investigated the 5-HT1B receptor-mediated presynaptic regulation of primary afferent synaptic transmission and mechanisms underlying this type of presynaptic inhibition.

Methods

Preparations

All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). The experiments were approved by the Kyungpook National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were carried out in accordance with the guiding principles for the care and use of animals approved by the Council of the Physiological Society of Korea and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Every effort was made to minimize both the number of animals used and their suffering.

Sprague–Dawley rats (12–16 days old) were decapitated under pentobarbital anaesthesia (50 mg·kg−1, i.p.). The brain stem was dissected and horizontally sliced at a thickness of 400 µm by use of a microslicer (VT1000S; Leica, Nussloch, Germany) in a cold artificial CSF (ACSF; 120 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 10 glucose, saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). Slices were kept in an ACSF saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at room temperature (22–25°C) for at least 1 h before electrophysiological recording. On the other hand, the strong stimulation of trigeminal tract might elicit trigeminal subnuclei-evoked EPSCs as well as primary afferent-evoked EPSCs, as glutamatergic transmission between trigeminal subnuclei has been demonstrated (Han et al., 2008). Immediately before recording, therefore, a surgical cut was made between trigeminal subnuclei interpolaris and caudalis without cutting the trigeminal tract to exclude possible activation of inter-subnuclei-evoked glutamate release. Thereafter, the slices were transferred into a recording chamber, and both the superficial dorsal horn of the Vc and trigeminal root was identified under an upright microscope (E600FN, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a water-immersion objective (×40). The ACSF routinely contained 10 µM SR95531, 1 µM strychnine, 50 µM dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) to block GABAA, glycine and NMDA receptors, respectively. In experiments with Ba2+ and Cd2+, KH2PO4 in ACSF was replaced with equimolar KCl. The bath was perfused with ACSF at 2 mL·min−1 by the use of a peristaltic pump (MP-1000, EYELA, Tokyo, Japan).

Electrical measurements

All electrical measurements were performed by use of a computer-controlled patch clamp amplifier (MultiClamp 700B; Molecular Devices; Union City, CA). For whole-cell recording, patch pipettes were made from borosilicate capillary glass (1.5 mm outer diameter, 0.9 mm inner diameter; G-1.5; Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) by use of a pipette puller (P-97; Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA). The resistance of the recording pipettes filled with internal solution (in mM; 140 CsMeHSO3, 5 TEA-Cl, 5 CsCl, 2 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP and 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 with Tris-base) was 4–6 MΩ. Membrane currents were filtered at 2 kHz (MultiClamp Commander; Molecular Devices), digitized at 5 kHz (Digidata 1322A, Molecular Devices) and stored on a computer equipped with pCLAMP 10.0 (Molecular Devices). In whole-cell recordings, 10 mV hyperpolarizing step pulses (30 ms in duration) were periodically delivered to monitor the access resistance (15–20 MΩ), and recordings were discontinued if the access resistance changed by more than 15%. All electrophysiological experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C). To record action potential-dependent glutamatergic EPSCs, a glass stimulation pipette (∼10 µm diameter) filled with a bath solution, was positioned around the spinal trigeminal tract (3–6 mm rostral to the border between the trigeminal subnuclei interpolaris and caudalis; see Figure 1A). Brief paired pulses (500 µs, 100–200 µA, 10 Hz) were applied by the stimulation pipette at a frequency of 0.1 Hz using a stimulator (SEN-7203, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an isolator unit (SS-701J, Nihon Kohden).

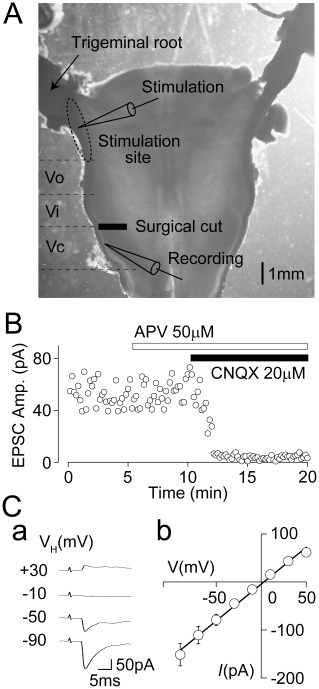

Figure 1.

Properties of primary afferent-evoked glutamatergic EPSCs. (A) A photograph of the horizontal brainstem slice. A surgical cut was made between the trigeminal subnuclei interpolaris and caudalis without cutting the trigeminal tract. Sites of the recording and stimulation were indicated (see also Methods for details). Vi; interpolaris, Vo; oralis. (B) A typical time course of EPSC amplitude before and during the application of 50 µM APV and 10 µM CNQX in the presence of both 10 µM SR95531 and 1 µM strychnine. Note that primary afferent-evoked glutamatergic EPSCs were completely blocked by CNQX but not APV. (Ca) Typical traces of primary afferent-evoked glutamatergic EPSCs at various holding potentials (VH). In these experiments, primary afferent-evoked glutamatergic EPSCs were recorded in the presence of 50 µM APV, 10 µM SR95531 and 1 µM strychnine. (Cb) A plot of the mean amplitude of EPSCs at various VH values. The continuous line is the least-squares linear fit to the mean EPSC values at each VH (r2= 0.90). The calculated reversal potential was 2.9 mV. Each point represents the mean and SEM from seven experiments.

Data analysis

The amplitudes of action potential-dependent glutamatergic EPSCs were calculated by subtracting the baseline from the peak amplitude. The conduction velocity of primary afferents innervating SG neurons of the Vc was calculated by dividing the distance between stimulation and recording sites by the latency of EPSCs. Since the latency of EPSCs consists of the conduction time of action potential and the synaptic delay, the EPSC latency was further compensated by subtracting 0.6 ms, which is the experimentally calculated synaptic delay at thalamocortical excitatory synapses (Salami et al., 2003), from the onset time of EPSCs. However, the influence of synaptic delay on the conduction velocity of primary afferents in the spinal cord might be negligible (Nakatsuka et al., 2000). The effect of drugs on EPSCs was quantified as a percentage change in EPSC amplitude compared with the control values. Spontaneous miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were counted and analysed using the MiniAnalysis programme (Synaptosoft, Inc., Decatur, GA) as described previously (Jang et al., 2002). Briefly, mEPSCs were screened automatically using an amplitude threshold of 10 pA and then visually accepted or rejected based upon the rise and decay times. Basal noise levels during voltage-clamp recordings were less than 10 pA. The average values of both the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs during the control period (10–20 min) were calculated for each recording, and the frequency and amplitude of all the events during the CP93129 application (5 min) were normalized to these values. The effects of these different conditions were quantified as a percentage increase in mEPSC frequency compared with the control values. The inter-event intervals and amplitudes of a large number of synaptic events obtained from the same neuron were examined by constructing cumulative probability distributions and compared using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) test with Stat View software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The continuous curve for the concentration–inhibition relationship was fitted using a least-squares fit to the following equation:

where I is the inhibition ratio of CP93129-induced EPSC amplitude, C is the concentration of CP93129, EC50 is the concentration for the half-effective response and nH is the Hill coefficient. Numerical values are provided as the mean and SEM using values normalized to the control. Significant differences in the mean amplitude and frequency were tested using Student's two-tailed paired t-test, using absolute values rather than normalized ones. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Drugs

The drugs used in the present study were 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV), strychnine, nifedipine, forskolin (from Sigma, St. Louis, MO), CP93129, GR55562, LY310762, SQ22536, SR95531, SB224289, tetrodotoxin (TTX) (from Tocris, Bristol, UK) and ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-AgTx), ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTx) (from Peptide institute, Osaka, Japan). Sumatriptan was kindly gifted from Yuyu Pharma. Inc. (Seoul, Korea). All drugs were applied by bath application (2 mL·min−1). The drug/molecular target nomenclature conforms to BJP's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011).

Results

CP93129 acts presynaptically to inhibit glutamate release in Vc neurons

In the presence of 1 µM strychnine and 10 µM SR95531, which blocks glycine and GABAA receptors, action potential-dependent synaptic currents were recorded from SG neurons of the Vc at a VH of −60 mV by electrical stimulation through a glass pipette placed to the spinal trigeminal tract (Figure 1A). In all SG neurons tested, these synaptic currents were not affected by 50 µM APV, a selective NMDA receptor antagonist, but they were completely blocked by 10 µM CNQX, a selective AMPA/KA receptor antagonist (Figure 1B). Figure 1C shows typical synaptic currents at various VH conditions and their current–voltage (I–V) relationship (n= 7). The reversal potential of synaptic currents estimated from the I–V relationship was 2.9 mV, which was very similar to the theoretical equilibrium potential of monovalent cations. These results indicate that the synaptic currents are glutamatergic EPSCs mediated by Ca2+-impermeable AMPA/KA receptors based on their linear I–V relationship (Burnashev et al., 1995). On the other hand, the calculated conduction velocity of primary afferents innervating SG neurons of the Vc was 1.45 ± 0.87 m·s−1 (SD in the range 0.19–4.44 m·s−1, n= 60; see also Figure 2D). This calculated conduction velocity is similar to that estimated from Aδ- and/or C-fibres of rat sciatic nerve at 22°C (Pinto et al., 2008), indicating that most of EPSCs recorded in the present study are likely to have originated from Aδ- and/or C-fibres.

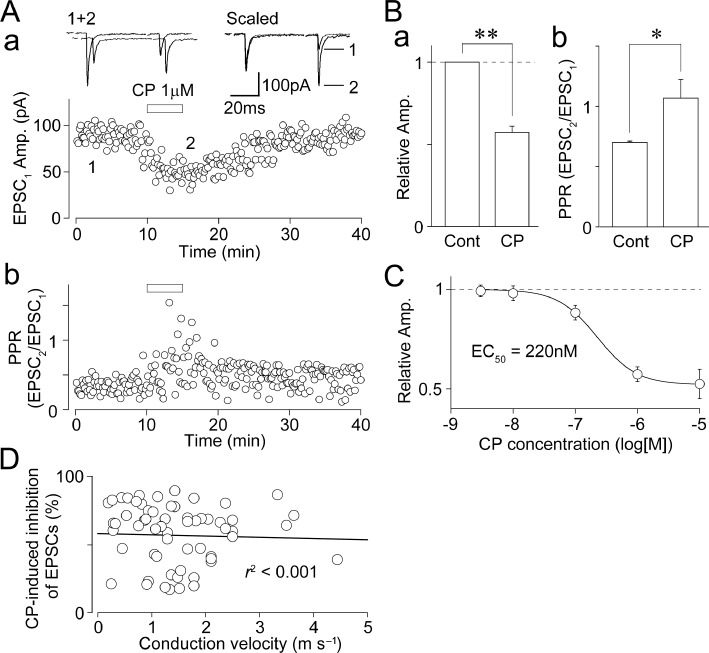

Figure 2.

Effect of CP93129 on primary afferent-evoked glutamatergic EPSCs. (A) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude (a) and PPR (EPSC2/EPSC1; b) before, during and after application 1 µM CP93129. The amplitudes of all EPSCs were plotted. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (B) CP93129-induced changes in the EPSC1 amplitude (a) and PPR (b). Each column was normalized to the control and represents the mean and SEM from 20 experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (C) Concentration–response relationship of CP93129. The EC50 value calculated from curve fitting result was 220 nM. Each point and error bar represents the mean and SEM from six to eight experiments. (D) A scatter plot of the extent of CP93129 (1 µM)-induced inhibition of EPSCs against the calculated conduction velocity of primary afferents innervating SG neurons of the Vc. The continuous line is the least-squares linear fit (r2 < 0.001, n= 60).

In order to investigate whether presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors modulate action potential-dependent glutamatergic synaptic transmission onto SG neurons, all the following experiments were performed in the presence of 1 µM strychnine, 10 µM SR95531 and 50 µM APV. In these conditions, the effect of CP93129 on glutamatergic EPSCs evoked by pairing stimulation at an interval of 50 ms (20 Hz) was observed. CP93129 (1 µM), a selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist [EC50= 56 nM in rat substantia nigra (Macor et al., 1990); see also Chopin et al., 1994], inhibited primary afferent-evoked glutamate release in more than half of SG neurons tested (148 of 255 neurons, 58%). In 20 SG neurons, in which the inhibitory effect of CP93129 on glutamatergic EPSCs was fully analysed, CP93129 (1 µM) reversibly decreased the first EPSC (EPSC1) amplitude to 57.3 ± 3.7% of the control (n= 20, P < 0.01; Figure 2A and B) and increased the paired-pulse ratio (PPR; EPSC2/EPSC1) from 0.68 ± 0.10 to 1.07 ± 0.20 (n= 20, P < 0.01; Figure 2A and B), suggesting that CP93129 acts presynaptically to decrease the probability of glutamate release. In addition, CP93129 clearly inhibited glutamatergic EPSCs in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 value of 220 nM (Figure 2C). On the other hand, there is no relationship between the extent of CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs and the calculated conduction velocity of primary afferents innervating SG neurons of the Vc (r2 < 0.001, n= 60; Figure 2D).

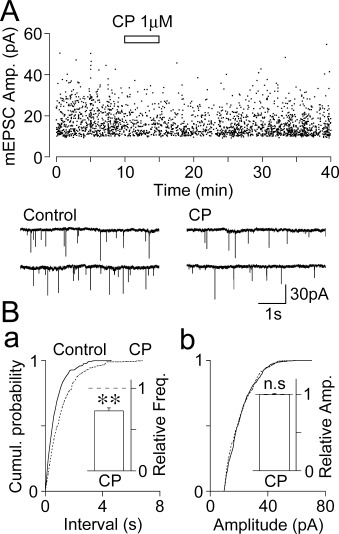

In a subset of experiments, we examined the effect of CP93129 on glutamatergic mEPSCs. Glutamatergic mEPSCs were recorded from SG neurons in the presence of 300 nM TTX, which completely blocks voltage-dependent Na+ channels, 50 µM APV, 10 µM SR95531 and 1 µM strychnine. In 8 of 10 SG neurons tested, in which the effect of CP93129 was fully analysed, CP93129 (1 µM) decreased the mean mEPSC frequency to 72.6 ± 3.7% of the control (n= 8, P < 0.01), without affecting the mean mEPSC amplitude (99.7 ± 1.6% of the control, n= 8, P= 0.63; Figure 3A and B insets). CP93129 significantly shifted the distribution of the inter-event interval to the right (P < 0.01, K-S-test; Figure 3Ba), indicating a decrease in mEPSC frequency. However, CP93129 did not change the distribution of the current amplitude (P= 0.69, K-S test; Figure 3Bb). In addition, CP93129 (1 µM) decreased the mean mEPSC frequency even in the presence of 100 µM Cd2+, a general voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC) blocker (63.4 ± 7.7% of the Cd2+ condition, n= 5, P < 0.01), without affecting the mean mEPSC amplitude (100.1 ± 2.9% of the Cd2+ condition, n= 5, P= 0.73). The results again suggest that CP93129 acts presynaptically to reduce the probability of glutamate release onto SG neurons of the Vc.

Figure 3.

Effect of CP93129 on glutamatergic mEPSCs. (A) An all-point scatter plot of the amplitude of glutamatergic mEPSCs before, during and after the application of 1 µM CP93129; 2157 events were plotted. Insets represent typical traces with an expanded time scale. (B) Cumulative probability distributions for the inter-event interval (a; P < 0.01, K-S test) and current amplitude (b; P= 0.69, K-S test) of glutamatergic mEPSCs shown in (A); 468 for the control and 351 events for CP93129 were plotted. Insets, CP93129 (1 µM)-induced changes in mEPSC frequency (left) and amplitude (right). Each column represents the mean and SEM from eight experiments. **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant.

5-HT1B receptors are responsible for the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamate release

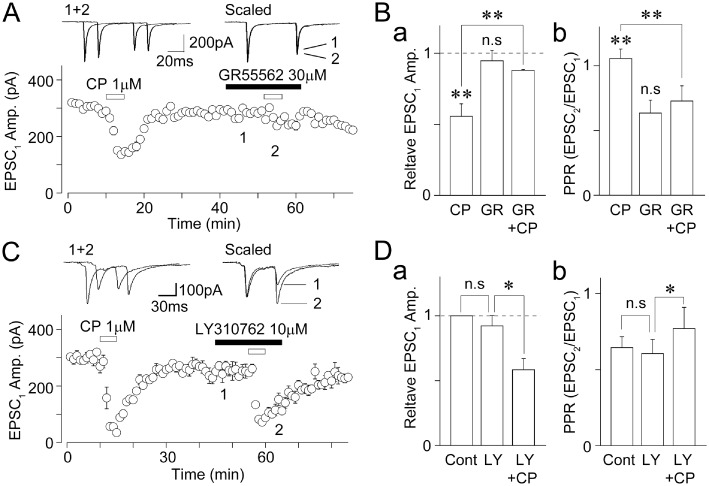

In order to verify whether presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors are responsible for the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamate release, we examined the effect of GR55562, a 5-HT1B/1D receptor antagonist (pKi= 7.3 and 6.3 for 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors, respectively; Connor et al., 1995), on the CP93129-induced decrease in EPSCs. The extent of CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs (55.6 ± 8.9% of the control, n= 6) was greatly reduced in the presence of 30 µM GR55562 (88.0 ± 0.7% of the GR55562 condition, n= 6, P < 0.01; Figure 4A and B). In addition, the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was significantly reduced in the presence of 30 µM SB224289, a more selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist (pKi= 8.0 and 6.2 for 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors, respectively; Roberts et al., 1997) (64.0 ± 8.8% of the control and 87.3 ± 8.0% of the SB224289 condition, n= 5, P < 0.05; data not shown). In addition, CP93129 failed to decrease glutamatergic EPSCs in the presence of both GR55562 and SB224289 (98.7 ± 3.2% of the GR55562 and SB224289 condition, n= 4, P= 0.10; data not shown). Neither GR55562 nor SB224289 had an effect on either the EPSC amplitude or the PPR (Figure 4Bb and Table S1), indicating that there is little tonic activation of presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors. In contrast, CP93129 (1 µM) still decreased EPSCs in the presence of 10 µM LY310762, a selective 5-HT1D receptor antagonist (IC50= 31 nM, Pullar et al., 2004) (61.3 ± 8.5% of the LY310762 condition, n= 5, P < 0.05; Figure 4C and D), suggesting that 5-HT1B receptors are responsible for the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamate release.

Figure 4.

Effects of 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptor antagonists on the CP93129-induced decrease in EPSCs. (A) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 30 µM GR55562. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (B) CP93129-induced changes in the EPSC1 amplitude (a) and PPR (b) in the absence or presence of 30 µM GR55562. Each column was normalized to the control and represents the mean and SEM from six experiments. **P < 0.01. (C) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 10 µM LY310762. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (D) CP93129-induced changes in the EPSC1 amplitude (a) and PPR (b) in the presence of 10 µM LY310762. Each column was normalized to the control and represents the mean and SEM from six experiments. *P < 0.05.

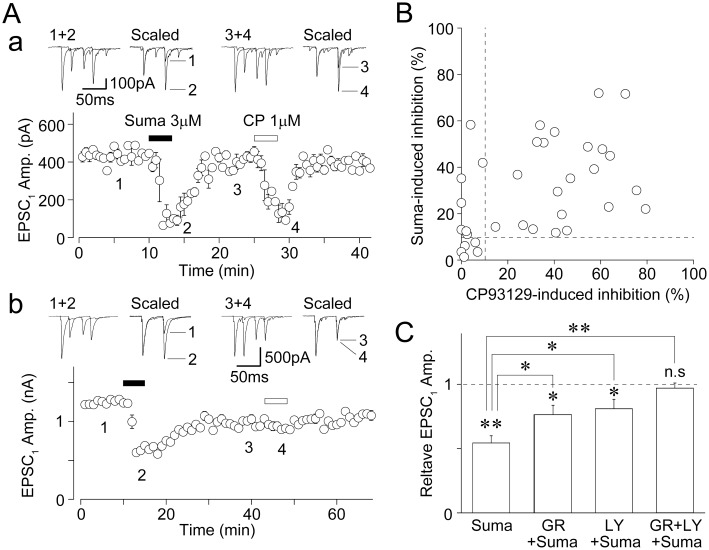

Since a previous study has shown that sumatriptan acts on 5-HT1D receptors to inhibit the primary afferent-evoked glutamate release onto SG neurons of the Vc (Jennings et al., 2004), we further examined the effect of sumatriptan, a 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonist (pKi= 7.8 and 8.1 for 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors, respectively; Dupuis et al., 1999), on glutamatergic EPSCs. In 29 of 34 neurons tested, sumatriptan (3 µM) decreased glutamatergic EPSCs to 65.6 ± 3.5% of the control (n= 29, P < 0.01; Figure 5A and B), and increased the PPR from 0.57 ± 0.05 to 0.94 ± 0.07 (n= 29, P < 0.01, data not shown), suggesting that sumatriptan also acts presynaptically to decrease the probability of glutamate release. In 22 of 29 neurons responding to sumatriptan, CP93129 (1 µM) also decreased glutamatergic EPSCs to 52.7 ± 3.7% of the control (n= 22, P < 0.01; Figure 5Aa and B). In the remaining 7 of 29 neurons responding to sumatriptan, however, CP93129 had no inhibitory effect (<10% inhibition) on glutamatergic EPSCs (Figure 5Ab and B). On the other hand, both sumatriptan and CP93129 had no inhibitory effect on glutamatergic EPSCs in 5 of 34 neurons tested (Figure 5B). The extent of sumatriptan-induced decrease in EPSCs (54.4 ± 5.6% of the control, n= 8) was significantly but not completely blocked by either 10 µM LY310762 (77.4 ± 7.8% of the LY310762 condition, n= 6, P < 0.05) or 30 µM GR55562 (76.4 ± 7.3% of the GR55562 condition, n= 8, P < 0.05) (Figure 5C). In addition, sumatriptan failed to decrease glutamatergic EPSCs in the presence of both LY310762 and GR55562 (95.2 ± 7.2% of the LY310762 and GR55562 condition, n= 6, P= 0.23; Figure 5C and Table S2). These results suggest that sumatriptan acts on both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors to inhibit glutamate release.

Figure 5.

Effects of sumatriptan on glutamatergic EPSCs. (A) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 3 µM sumatriptan (Suma) and 1 µM CP93129. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. Note that both sumatriptan and CP93129 had an inhibitory effect on glutamatergic EPSCs in most of neurons tested (a). However, only sumatriptan had an inhibitory effect on glutamatergic EPSCs in a subset of neurons tested (b). (B) The extent of sumatriptan- and CP93129-induced decrease in glutamatergic EPSCs in the same neurons. Results from 34 neurons were plotted. Dotted lines; 10% inhibition. (C) Sumatriptan-induced changes in the EPSC1 amplitude in the absence and presence of 30 µM GR55562, 10 µM LY310762 or both antagonists. Each column was normalized to the control and represents the mean and SEM from six to eight experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Mechanisms underlying the 5-HT1B receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of primary afferent-evoked glutamate release

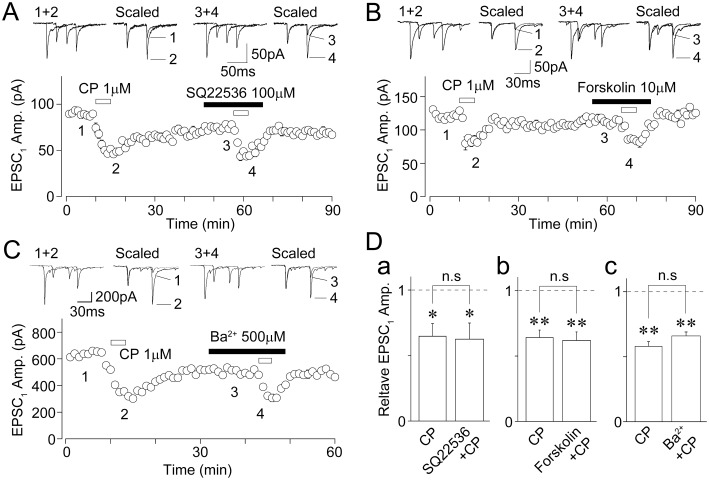

5-HT1B receptors are seven-transmembrane proteins coupled to Gi/o proteins and negatively coupled to AC, which increases intracellular cAMP concentration (Barnes and Sharp, 1999; Brown and Sihra, 2008). If presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors decrease glutamate release by inhibiting AC, the direct blockade of AC should decrease the glutamatergic EPSC amplitude. However, this was not the case because SQ22536, a selective AC inhibitor (Turcato and Clapp, 1999; Yum et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2009), even at a 100 µM concentration, had no effect on EPSCs (93.5 ± 12.0% of the control, n= 5, P= 0.47; Figure 6A). In addition, the extent of CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs (64.8 ± 9.6% of the control, n= 5) was not affected by 100 µM SQ22536 (62.5 ± 12.3% of the SQ22536 condition, n= 5, P= 0.66; Figure 6A and Da). We also examined the effect of forskolin, an AC activator (Laurenza et al., 1989; Yum et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2009), on the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamatergic EPSCs. Forskolin at a 10 µM concentration did not change EPSCs (91.7 ± 8.0% of the control, n= 9, P= 0.38; Figure 6B). In addition, forskolin had no effect on the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs (64.1 ± 5.7% of the control and 61.9 ± 6.5% of the forskolin condition, n= 9, P= 0.85; Figure 6B and Db). We next examined the effect of Ba2+, a G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channel blocker (Gerber et al., 1989; Yum et al., 2008), on the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs. Ba2+ at a 500 µM concentration did not change EPSCs (105.1 ± 5.2% of the control, n= 7, P= 0.47; Figure 6C). In addition, Ba2+ had no effect on the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs (57.9 ± 4.7% of the control and 65.3 ± 3.6% of the Ba2+ condition, n= 7, P= 0.11; Figure 6C and Dc). The results suggest that neither AC-cAMP pathways nor GIRK channels are involved in the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamatergic EPSCs.

Figure 6.

Effects of SQ22536, forskolin and Ba2+ on the CP93129-induced decrease in EPSCs. (A) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 100 µM SQ22536. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (B) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 10 µM forskolin. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (C) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 500 µM Ba2+. The amplitudes of 6 EPSCs were averaged and plotted. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (D) Changes in the CP93129-induced decrease in EPSC1 amplitude in the absence and presence of SQ22536 (n= 5, a), forskolin (n= 9, b), and Ba2+ (n= 7, c). Each column was normalized to the control and represents the mean and SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

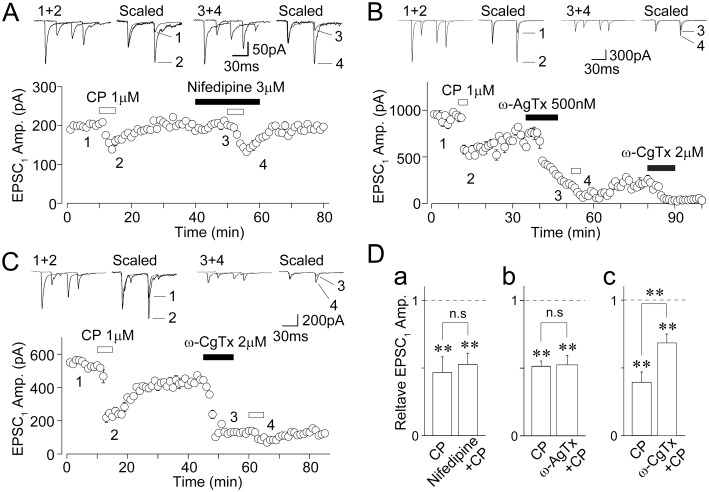

Multiple types of VDCCs control the neurotransmitter release, and especially, N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels are closely involved in the action potential-dependent neurotransmitter release (Wu and Saggau, 1997). In addition, the activation of presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors inhibits VDCCs to decrease neurotransmitter release at central synapses (Mizutani et al., 2006; Xiao et al., 2008). Therefore, we examined the effects of specific VDCC blockers on the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs. Nifedipine (10 µM), a selective L-type VDCC blocker, had little effect on EPSCs (92.4 ± 6.6% of the control, n= 6, P= 0.38; Figure 7A), suggesting that L-type VDCCs do not contribute to glutamate release from primary afferent terminals. In the presence of 10 µM nifedipine, the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was not affected (46.6 ± 11.6% of the control and 52.5 ± 8.4% of the nifedipine condition, n= 6, P= 0.57; Figure 7A and Ba). ω-AgTx (500 nM), a selective P/Q-type VDCC blocker, significantly decreased EPSC amplitude (35.9 ± 6.5% of the control, n= 4, P < 0.01; Figure 7B). After treatment with 500 nM ω-AgTx, however, the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was not affected (51.4 ± 3.9% of the control and 52.4 ± 6.9% of the ω-AgTx condition, n= 4, P= 0.58; Figure 7B and Bb), indicating that P/Q-type VDCCs might be not involved in the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs. ω-CgTx (2 µM), a selective N-type VDCC blocker, also significantly decreased EPSCs (33.4 ± 7.6% of the control, n= 7, P < 0.01; Figure 7C). After the treatment with 2 µM ω-CgTx, the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was significantly reduced (38.9 ± 9.3% of the control and 68.3 ± 6.6% of the ω-CgTx condition, n= 7, P < 0.01; Figure 7C and Bc). SNX-482 (1 µM), a selective R-type VDCC blocker, had little effect on EPSCs (99.5 ± 1.0% of the control, n= 4, P= 0.97). In the presence of 1 µM SNX-482, the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was not affected (45.1 ± 5.2% of the control and 55.8 ± 10.2% of the SNX-482 condition, n= 4, P= 0.54). On the other hand, the cumulative application of both 500 nM ω-AgTx and 2 µM ω-CgTx abolished all glutamatergic EPSCs (Figure 7B), suggesting that primary afferent-evoked EPSCs were mediated by the Ca2+ influx passing through both presynaptic N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels.

Figure 7.

Effects of specific VDCC antagonists on the CP93129-induced decrease in EPSCs. (A) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 3 µM nifedipine. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (B) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 500 nM ω-AgTx. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (C) A typical time course of the EPSC1 amplitude before, during and after application of 1 µM CP93129 in the absence or presence of 2 µM ω-CgTx. All points and error bars represent the mean and SEM of six EPSCs. Insets represent typical traces of the numbered region. (D) Changes in the CP93129-induced decrease in EPSC1 amplitude in the absence and presence of nifedipine (n= 6, a), ω-AgTx (n= 4, b), and ω-CgTx (n= 7, c). Each column was normalized to the control and represents the mean and SEM. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

5-HT1 receptors are known to inhibit the release of a number of neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, GABA, glycine, catecholamines and 5-HT itself, as heteroreceptors or autoreceptors at central synapses (Feuerstein, 2008; Jeong et al., 2008; Guo and Rainnie, 2010). Although 5-HT1 receptors are further divided into 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, and 5-HT1F receptors, most of the previous studies have shown that either 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptors are mainly involved in the presynaptic inhibition of neurotransmitter release (Feuerstein, 2008). In contrast, a few studies have suggested the involvement of 5-HT1D receptors in the presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release (Travagli and Williams, 1996; Maura et al., 1998). In the present study, several lines of evidence support the conclusion that presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors are responsible for the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamatergic EPSCs. Firstly, exogenously applied CP93129, a selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist, simultaneously decreased glutamatergic EPSC amplitude and increased the PPR. In addition, CP93129 decreased glutamatergic mEPSC frequency without affecting the current amplitude, although a further study is needed to elucidate whether the origin of mEPSCs is primary afferents. These results suggest that CP93129 acts presynaptically to decrease the probability of glutamate release from primary afferent terminals. Secondly, the CP93129-induced inhibition of glutamatergic EPSCs was significantly blocked by 5-HT1B/1D but not 5-HT1D receptor antagonists. Taken together, our present results provide evidence that functional 5-HT1B receptors are expressed on trigeminal primary afferents, and that their activation decreases action potential-dependent and spontaneous glutamate release onto SG neurons of the Vc.

Travagli and Williams (1996) have suggested that 5-HT1D receptors are responsible for the sumatriptan-induced inhibition of glutamate release onto medullary dorsal horn neurons of adult guinea-pigs. This conclusion might be derived from the use of sumatriptan as a potent agonist for only 5-HT1D receptors rather than 5-HT1B receptors, although sumatriptan is now regarded as an agonist for 5-HT1B/1D receptors. In addition, since Travagli and Williams (1996) did not examine the effects of 5-HT1D or 5-HT1B receptor antagonists on the sumatriptan-induced inhibition of glutamate release, it is still not clear whether sumatriptan acts only on 5-HT1D receptors to decrease glutamate release. On the other hand, Jennings et al. (2004) have shown that sumatriptan, via the activation of 5-HT1D rather than 5-HT1B receptors, reduces either the amplitude of evoked EPSCs or the frequency of mEPSCs in SG neurons of the Vc (Jennings et al., 2004). This conclusion is based on lack of effect of CP93129 on the frequency of glutamatergic mEPSCs, although CP93129 clearly decreased the frequency of mEPSCs in the present study. One difference between the previous and present studies is the position of the stimulating electrodes used to stimulate primary afferents; in the previous study, the trigeminal tract was about 1 mm rostral to the site of recording (Jennings et al., 2004) and, in the present study, the trigeminal tract was about 3–6 mm rostral to the border between the trigeminal subnuclei interpolaris and caudalis. Further, strong stimulation of the trigeminal tract might elicit trigeminal subnuclei-evoked EPSCs as well as primary afferent-evoked EPSCs. Another difference between the previous and present studies is the temperature; in the previous study it was 34°C (Jennings et al., 2004) and in our study it was room temperature (22–25°C). Temperature is an important factor that influences the activity of receptors. Although these possibilities were not tested in the present study, further studies should be done to explain the apparent discrepancy between these two studies.

On the other hand, other 5-HT receptor subtypes including 5-HT1B receptors might contribute to the sumatriptan-induced inhibition of glutamatergic EPSCs, because the inhibitory effect of sumatriptan on glutamatergic EPSCs seems to be partially blocked by the 5-HT1D receptor antagonist (Jennings et al., 2004). In addition, Jennings et al. did not examine the effect of CP93129 on action potential-dependent EPSCs. In the present study, we also found that sumatriptan has an inhibitory effect on glutamatergic EPSCs in the majority of Vc neurons tested, and that the sumatriptan-induced decrease in glutamatergic EPSCs was partially attenuated by adding either 5-HT1B or 5-HT1D receptor antagonists, and completely blocked by adding both antagonists. Further, since CP93129 decreased glutamatergic EPSCs in most of the Vc neurons responding to sumatriptan, the majority of primary afferent terminals is likely to express both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors. This conclusion is further supported by previous immunohistochemical studies showing that 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors are extensively expressed in small- and medium-sized TG neurons, and they are even colocalized in the same TG neurons (Wotherspoon and Priestley, 2000; Ma et al., 2001). However, it should be noted that a subset of primary afferent terminals might express only 5-HT1D receptors, because CP93129 had no inhibitory effect on glutamatergic EPSCs of Vc neurons responding to sumatriptan.

Although it has been well documented that 5-HT1B receptors are coupled to Gi/o proteins and that their activation results in a decrease in cAMP production, the increase in K+ conductance and the inhibition of VDCCs (Barnes and Sharp, 1999; Brown and Sihra, 2008), mechanisms underlying the 5-HT1B receptor-mediated inhibition of neurotransmitter release are poorly understood. In the present study, the contribution of either cAMP or GIRK channels to the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs would be negligible because both the specific inhibitor and activator of AC and GIRK channel blocker had no effect on the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs. In contrast, we found that the extent of CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs was significantly reduced by adding ω-CgTx (N-type blocker), but not nifedifine (L-type blocker), ω-AgTx (P/Q-type blocker) or SNX-482 (R-type blocker), suggesting that the CP93129-induced inhibition of EPSCs is mainly mediated by the inhibition of Ca2+ entry through presynaptic N-type Ca2+ channels. On the other hand, we also found that CP93129 still decreased the frequency of mEPSCs even in the presence of Cd2+. Since miniature currents are generally independent of extracellular Ca2+ or VDCCs (Scanziani et al., 1992; Capogna et al., 1993), these results suggest that presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors reduce action potential-independent glutamate release by acting on the release machinery downstream of the presynaptic Ca2+ entry (Wu and Saggau, 1997). These additional direct effects on the presynaptic vesicular release machinery might also contribute to the 5-HT1B receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of action potential-dependent glutamate release (see also Wu and Saggau, 1997). However, it should be noted that mechanisms operating at room temperature might be not the same as those prevailing at physiological temperature.

Triptans, such as sumatriptan, naratriptan and zolmitriptan, have a selective analgesic action on some types of cranial pain, including migraine and cluster headache (Ekbom et al., 1995; Ahn and Basbaum, 2005), but not facial or somatic pain (Dao et al., 1995; Antonaci et al., 1998). In peripheral tissues, the anti-migraine action of triptans is mainly mediated by both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors. For example, smooth muscle cells in cranial blood vessels express 5-HT1B receptors (Hamel et al., 1993; Longmore et al., 1998), and the activation of 5-HT1B receptors directly elicits vasoconstriction (Humphrey and Feniuk, 1991). However, as trigeminovascular sensory neurons in humans express 5-HT1D rather than 5-HT1B receptors (Longmore et al., 1997; Potrebic et al., 2003), 5-HT1B receptors might be not involved in the anti-migraine action of triptans in trigeminovascular sensory neurons. In addition, previous studies have shown that 5-HT1D receptors in humans contribute to the triptan-mediated vasoconstriction by inhibiting the release of vasodilatory neuropeptides, for example, calcitonin gene-related peptide, from the peripheral terminals of trigeminal sensory neurons (Longmore et al., 1997; but see also Shepherd et al., 1997). Similarly, sumatriptan, via the activation of 5-HT1D, rather than 5-HT1B, receptors has been shown to reduce glutamate release onto SG neurons of the Vc (Jennings et al., 2004). Although these previous studies suggest that 5-HT1B receptors are not involved in the anti-migraine action of triptans in trigeminovascular sensory neurons, recent studies have suggested that a central trigeminal action of triptans, which is mediated by 5-HT1B rather than 5-HT1D receptors could be involved in the processing of craniovascular pain (Muñoz-Islas et al., 2006; 2009). Further studies are needed to verify whether 5-HT1B receptors can inhibit glutamate release from trigeminovascular afferents onto Vc neurons. On the other hand, 5-HT1B receptors are expressed in neurons within the TG as well as dorsal root ganglia (Pierce et al., 1996; Hou et al., 2001). In addition, many 5-HT1B-positive neurons are known to be Aδ- or C-fibre neurons, which also contain calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P (Wotherspoon and Priestley, 2000; Ma et al., 2001), suggesting that 5-HT1B receptors might have an analgesic effect on cranial as well as non-cranial pain by decreasing the excitability of nociceptive afferents. In fact, a recent study has shown that triptans have an analgesic action in animal models of non-cranial pain including somatic and visceral pain (Nikai et al., 2008), although it is not known whether such antinociceptive effects of triptans on non-cranial pain are mediated by 5-HT1B and/or 5-HT1D receptors.

In conclusion, we have shown that the activation of presynaptic 5-HT1B receptors decreases glutamate release from trigeminal primary afferents, presumably nociceptive Aδ- and C-fibres, onto SG neurons of the Vc. Together with previous immunohistochemical studies, the present results suggest that 5-HT1B receptors could be a potential target for the treatment of pain from orofacial tissues.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010–0029459).

Glossary

- ω-AgTx

ω-agatoxin IVA

- APV

dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid

- ω-CgTx

ω-conotoxin GVIA

- CP93129

3-(1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)-1,4-diydropyrrolo[3,2-b]pyridine-5-one

- GIRK

G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+

- GR55562

3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-pyridin-4-ylphenyl)benzamide

- I-V

current–voltage

- K-S

Kolmogorov–Smirnov

- LY310762

3,3-dimethyl-1-(2-[4-(4-fluorobenzoyl)piperidin-1-yl]-1-ethyl)-1,3-diydro-2H-indol-2-one

- mEPSCs

miniature EPSCs

- PPR

paired-pulse ratio

- SB224289

1′-methyl-5-[[2′-methyly-4′-(5-methyl-1,2,3-oxadiazol-3-yl)biphenyl-4-yl[carbonyl]-2,3,6,7-tetrahydrospiro[furo[2,3-f]indole-3,4′-piperidine hydrochloride

- SG

substantia gelatinosa

- SR95531

6-imino-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1(6H)-pyridazinebutanoic acid HBr

- SQ22536

9-(tetrahydro-2-furanyl)-9H-purin-6-amine

- TG

trigeminal ganglia

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- Vc

trigeminal subnucleus caudalis

- VDCCs

voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

Statement of conflicts of interest

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 CP93129-induced changes in paired-pulse ratio in the absence and presence of various drugs. Data represent the mean and SEM of paired-pulse ratio

Table S2 Sumatriptan-induced changes inpaired-pulse ratio in the absence and presence of 5-HT1Band 5-HT1D receptor antagonists. Data represent the mean and SEM of paired-pulse ratio

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Ahn AH, Basbaum AI. Where do triptans act in the treatment of migraine? Pain. 2005;115:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 5th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambalavanar R, Morris R. The distribution of binding by isolectin I-B4 from Griffonia simplicifolia in the trigeminal ganglion and brainstem trigeminal nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1992;47:421–429. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonaci F, Pareja JA, Caminero AB, Sjaastad O. Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua: lack of efficacy of sumatriptan. Headache. 1998;38:197–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3803197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1083–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Sihra TS. Presynaptic signaling by heterotrimeric G-proteins. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;184:207–260. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-74805-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Zhou Z, Neher E, Sakmann B. Fractional calcium currents through recombinant GluR channels of the NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;485:403–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Mechanism of µ-opioid receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition in the rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;470:539–558. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IS, Nakamura M, Cho JH, Park HM, Kim SJ, Kim J, et al. cAMP-mediated long-term facilitation of glycinergic transmission in developing spinal dorsal horn neurons. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1695–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopin P, Moret C, Briley M. Neuropharmacology of 5-hydroxytryptamine1B/D receptor ligands. Pharmacol Ther. 1994;62:385–405. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classey JD, Bartsch T, Goadsby PJ. Distribution of 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1F receptor expression in rat trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia neurons: relevance to the selective anti-migraine effect of triptans. Brain Res. 2010;1361:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor HE, Beattie DT, Feniuk WH, Umphrey PA, Mitchell W, Oxford A, et al. Use of GR55562, a selective 5-HT1D antagonist, to investigate 5-HT1D receptor subtypes mediating cerebral vasoconstriction. Cephalagia. 1995;15(Suppl. 14):99. [Google Scholar]

- Crissman RS, Sodeman T, Denton AM, Warden RJ, Siciliano DA, Rhoades RW. Organization of primary afferent axons in the trigeminal sensory root and tract of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:169–183. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960101)364:1<169::AID-CNE13>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao TT, Lund JP, Rémillard G, Lavigne GJ. Is myofascial pain of the temporal muscles relieved by oral sumatriptan? A cross-over pilot study. Pain. 1995;62:241–244. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00025-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLander GE, Hopkins CJ. Interdependence of spinal adenosinergic, serotoninergic and noradrenergic systems mediating antinociception. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:1791–1794. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deseure K, Koek W, Colpaert FC, Adriaensen H. The 5-HT1A receptor agonist F 13640 attenuates mechanical allodynia in a rat model of trigeminal neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;456:51–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis DS, Perez M, Halazy S, Colpaert FC, Pauwels PJ. Magnitude of 5-HT1B and 5-HT1A receptor activation in guinea-pig and rat brain: evidence from sumatriptan dimer-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding responses. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;67:107–123. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekbom K, Krabbe A, Micieli G, Prusinski A, Cole JA, Pilgrim AJ, et al. Cluster headache attacks treated for up to three months with subcutaneous sumatriptan (6 mg). Sumatriptan Cluster Headache Long-term Study Group. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:230–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.015003230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein TJ. Presynaptic receptors for dopamine, histamine, and serotonin. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;184:289–338. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-74805-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink KB, Göthert M. 5-HT receptor regulation of neurotransmitter release. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:360–417. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furue H, Katafuchi T, Yoshimura M. Sensory processing and functional reorganization of sensory transmission under pathological conditions in the spinal dorsal horn. Neurosci Res. 2004;48:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber U, Greene RW, Haas HL, Stevens DR. Characterization of inhibition mediated by adenosine in the hippocampus of the rat in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1989;417:567–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Williams JT, Travagli RA. Inhibition by 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline in substantia gelatinosa of guinea-pig spinal trigeminal nucleus. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;485:113–120. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JD, Rainnie DG. Presynaptic 5-HT1B receptor-mediated serotonergic inhibition of glutamate transmission in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Neuroscience. 2010;165:1390–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel E, Fan E, Linville D, Ting V, Villemure JG, Chia LS. Expression of mRNA for the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine1Dβ receptor subtype in human and bovine cerebral arteries. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SM, Ahn DK, Youn DH. Pharmacological analysis of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in horizontal brainstem slices preserving three subnuclei of spinal trigeminal nucleus. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;167:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou M, Kanje M, Longmore J, Tajti J, Uddman R, Edvinsson L. 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors in the human trigeminal ganglion: co-localization with calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P and nitric oxide synthase. Brain Res. 2001;909:112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D, Clarke DE, Fozard JR, Hartig PR, Martin GR, Mylecharane EJ, et al. International Union of Pharmacology classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin) Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:157–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey PP, Feniuk W. Mode of action of the anti-migraine drug sumatriptan. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:444–446. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90630-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin MF, Renenhan WE, Mooney RD, Rhoades RW. Structure-function relationships in rat medullary and cervical dorsal horns. I. Trigeminal primary afferents. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1153–1186. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IS, Jeong HJ, Katsurabayashi S, Akaike N. Functional roles of presynaptic GABAA receptors on glycinergic nerve terminals in the rat spinal cord. J Physiol (Lond) 2002;541:423–434. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.016535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings EA, Ryan RM, Christie MJ. Effects of sumatriptan on rat medullary dorsal horn neurons. Pain. 2004;111:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HJ, Chenu D, Johnson EE, Connor M, Vaughan CW. Sumatriptan inhibits synaptic transmission in the rat midbrain periaqueductal grey. Mol Pain. 2008;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser V, Aubel B, Hamon M, Bourgoin S. The antimigraine 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists, sumatriptan, zolmitriptan and dihydroergotamine, attenuate pain-related behaviour in a rat model of trigeminal neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:1287–1297. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenza A, Sutkowski EM, Seamon KB. Forskolin: a specific stimulator of adenylyl cyclase or a diterpene with multiple sites of action? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:442–447. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(89)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Li H, Kaneko T, Mizuno N. Substantia gelatinosa neurons in the medullary dorsal horn: an intracellular labeling study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;411:399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore J, Shaw D, Smith D, Hopkins R, McAllister G, Pickard JD, et al. Differential distribution of 5HT1D- and 5HT1B-immunoreactivity within the human trigemino-cerebrovascular system: implications for the discovery of new antimigraine drugs. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:833–842. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1708833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore J, Razzaque Z, Shaw D, Davenport AP, Maguire J, Pickard JD, et al. Comparison of the vasoconstrictor effects of rizatriptan and sumatriptan in human isolated cranial arteries: immunohistological demonstration of the involvement of 5-HT1B-receptors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:577–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00821.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucki I. The spectrum of behaviors influenced by serotonin. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QP, Hill R, Sirinathsinghji D. Colocalization of CGRP with 5-HT1B/1D receptors and substance P in trigeminal ganglion neurons in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:2099–2104. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macor JE, Burkhart CA, Heym JH, Ives JL, Lebel LA, Newman ME, et al. 3-(1,2,5,6-Tetrahydropyrid-4-yl)pyrrolo[3,2-b]pyrid-5-one: a potent and selective serotonin (5-HT1B) agonist and rotationally restricted phenolic analogue of 5-methoxy-3-(1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyrid-4-yl)indole. J Med Chem. 1990;33:2087–2093. doi: 10.1021/jm00170a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maura G, Marcoli M, Tortarolo M, Andrioli GC, Raiteri M. Glutamate release in human cerebral cortex and its modulation by 5-hydroxytryptamine acting at h 5-HT1D receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:45–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani H, Hori T, Takahashi T. 5-HT1B receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition at the calyx of Held of immature rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1946–1954. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Islas E, Gupta S, Jiménez-Mena LR, Lozano-Cuenca J, Sánchez-López A, Centurión D, et al. Donitriptan, but not sumatriptan, inhibits capsaicin-induced canine external carotid vasodilatation via 5-HT1B rather than 5-HT1D receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:82–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Islas E, Lozano-Cuenca J, González-Hernández A, Ramírez-Rosas MB, Sánchez-López A, Centurión D, et al. Spinal sumatriptan inhibits capsaicin-induced canine external carotid vasodilatation via 5-HT1B rather than 5-HT1D receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;615:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka T, Ataka T, Kumamoto E, Tamaki T, Yoshimura M. Alteration in synaptic inputs through C-afferent fibers to substantia gelatinosa neurons of the rat spinal dorsal horn during postnatal development. Neuroscience. 2000;99:549–556. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson R, Small J, Dixon AK, Spanswick D, Lee K. Serotonin receptor mRNA expression in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2003;337:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikai T, Basbaum AI, Ahn AH. Profound reduction of somatic and visceral pain in mice by intrathecal administration of the anti-migraine drug, sumatriptan. Pain. 2008;139:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata H, Saito S, Sakurazawa S, Sasaki M, Usui T, Goto F. Antiallodynic effects of intrathecally administered 5-HT2C receptor agonists in rats with nerve injury. Pain. 2004;108:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Imbe H, Tashiro A, Kimura A, Donishi T, Tamai Y, et al. The role of peripheral 5HT2A and 5HT1A receptors on the orofacial formalin test in rats with persistent temporomandibular joint inflammation. Neuroscience. 2005;130:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce PA, Xie GX, Levine JD, Peroutka SJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor subtype messenger RNAs in rat peripheral sensory and sympathetic ganglia: a polymerase chain reaction study. Neuroscience. 1996;70:553–559. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto V, Derkach VA, Safronov BV. Role of TTX-sensitive and TTX-resistant sodium channels in Aδ- and C-fiber conduction and synaptic transmission. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:617–628. doi: 10.1152/jn.00944.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrebic S, Ahn AH, Skinner K, Fields HL, Basbaum AI. Peptidergic nociceptors of both trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia express serotonin 1D receptors: implications for the selective antimigraine action of triptans. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10988–10997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10988.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullar IA, Boot JR, Broadmore RJ, Eyre TA, Cooper J, Sanger GJ, et al. The role of the 5-HT1D receptor as a presynaptic autoreceptor in the guinea pig. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;493:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SV, Yaksh TL. Spinal noradrenergic terminal system mediates antinociception. Brain Res. 1980;189:391–401. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Price GW, Gaster L, Jones BJ, Middlemiss DN, Routledge C. Importance of h5-HT1B receptor selectivity for 5-HT terminal autoreceptor activity: an in vivo microdialysis study in the freely-moving guinea-pig. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:549–557. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami M, Itami C, Tsumoto T, Kimura F. Change of conduction velocity by regional myelination yields constant latency irrespective of distance between thalamus and cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6174–6179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937380100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkühler J. The organization and function of endogenous antinociceptive systems. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50:49–81. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(96)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Capogna M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of miniature excitatory synaptic currents by baclofen and adenosine in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd SL, Williamson DJ, Beer MS, Hill RG, Hargreaves RJ. Differential effects of 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists on neurogenic dural plasma extravasation and vasodilation in anaesthetized rats. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:525–533. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper SJ, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD. Mechanisms of action of the 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1084–1088. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.7.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Williams JT. Endogenous monoamines inhibit glutamate transmission in the spinal trigeminal nucleus of the guinea-pig. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;491:177–185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcato S, Clapp LH. Effects of the adenylyl cyclase inhibitor SQ22536 on iloprost-induced vasorelaxation and cyclic AMP elevation in isolated guinea-pig aorta. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:845–847. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotherspoon G, Priestley JV. Expression of the 5-HT1B receptor by subtypes of rat trigeminal ganglion cells. Neuroscience. 2000;95:465–471. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Richter JA, Hurley JH. Release of glutamate and CGRP from trigeminal ganglion neurons: role of calcium channels and 5-HT1 receptor signaling. Mol Pain. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Wilson PR. Spinal serotonin terminal system mediates antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1979;208:446–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yum DS, Cho JH, Choi IS, Nakamura M, Lee JJ, Lee MG, et al. Adenosine A1 receptors inhibit GABAergic transmission in rat tuberomammillary nucleus neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;106:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.