Abstract

Purpose

Patterns of orbital lymphoma at diagnosis and follow-up are described. We also discuss differential diagnosis of orbital masses.

Materials and methods

This pictorial review contains 19 cases of orbital lymphoma before and after treatment. Superior-lateral quadrant and extra-conal location were observed predominantly. Effective response after treatment was presented on follow-up imaging, although few local relapses were found. Further follow-up showed no changes of residual images.

Discussion

Location of orbital masses can help in the differential diagnosis. Moreover, imaging features of lymphoma at diagnosis can be useful in planning surgical biopsy. Pattern of follow-up described may be relevant on monitoring imaging.

Teaching points

• Orbital lymphoma involves mainly superior-lateral quadrant and the orbital structures inside.

• Location of retrobulbar mass-like lesions are useful information in the differential diagnosis.

• Satisfactory response is detected after treatment, however relapse is noted, so follow-up is needed.

Keywords: Lymphoma, Orbital adnexa, Orbit, Magnetic resonance imaging, Computed tomography

Introduction

Orbital lymphoma represents a small fraction of all systemic lymphomas that account for approximately 1–2 % of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Lymphoma is reported to constitute between 6 and 8 % of orbital tumours, however, the incidence is estimated to be rising and has doubled in the last two decades [1, 2].

Lymphoproliferative disease includes a spectrum of disorders ranging from benign (lymphoid hyperplasia) to malignant disease (lymphoma), passing by atypical lymphoid hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological studies have been reliable to differentiate these entities. Orbital lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of malignancies, most of them are primary extranodal lymphoma of the marginal zone of mucosa associated with lymphoid tissue (MALT type lymphoma). These lymphomas arise in lymphoid tissue acquired in certain extranodal sites as a result of chronic inflammation or autoimmune disorders. Recent advances in molecular and cytogenetics establish that lymphoma can be associated with Chlamydia psittaci infection [3].

This tumour is seen more commonly in the 5th–7th decades of life with a slight female predominance. The orbital infiltration by lymphoma is characterised by a palpable, firm or rubbery mass. Other symptoms are progressive proptosis, decreased visual acuity, motility disturbances and diplopia. Occasionally, periorbital oedema is seen [4–6].

Background

The radiological findings found in orbital lymphoma have been previously reported in the literature. This tumour has been described as a mass with distinct margins, which shows an isointense signal on T1-weighted images and iso-hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Variable enhancement has been reported after contrast administration [7]. Previous published reports display useful information that can help to differentiate orbital lymphoma from other masses. Spiral computed tomography (CT) using a dual-phase contrast-enhancement protocol report that lymphomas have a decrease in density on delayed images, as opposed to orbital pseudotumours, whose density increases on delayed images [8]. Moreover, low values in the apparent diffusion coefficient on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been found helpful to discriminate lymphoma from other expansive orbital lesions [9].

Purpose

This review is focused on describing the patterns of orbital lymphoma. The characteristic distribution and infiltration of some orbital structures will define useful items to orientate a proper diagnosis. Additionally, this information can be helpful in ophthalmological surgery to obtain an optimal sample for accurate diagnosis. Differential diagnosis regarding the location of orbital masses will be developed in this article. Moreover, the patterns during follow-up and the frequency of relapses are described. This information will assist the radiologist for proper monitoring.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria in this retrospective study were: (1) histological confirmation of lymphoma by biopsy and (2) to have available radiological exams before and after treatment. Nineteen patients (11 men and eight women, age range 37–80 years, mean 60) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Fifteen cases were examined by CT and four by MRI.

Imaging of the orbit was performed by CT with the following technique: voltage: 120 kV, current: 150 mA, rotation time: 0.65 s, dose profile average: DLP: 175 mGy·cm and CTDIvol: 20 mGy and/or a 1.5-T MRI system. Axial acquisition and coronal reconstruction without and with contrast was done on CT scans. The MRI protocol included: axial and coronal T2-weighted imaging and T1 without and with contrast, and fat suppression T1-weighted imaging after contrast.

Informed consent for clinical radiological exams were obtained for all patients included in this retrospective research. Most lymphomas included in the study were MALT category, other histological subtypes found were as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Histological subtypes of orbital lymphoma

| Lymphoma subtypes | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma (MALT) | 16 |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 2 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 1 |

In order to make a proper description of the tumour, the orbit was divided into four separated quadrants. Taking into account this classification, number of involved quadrants (1/2/3/4) and dominant quadrant (superior-lateral/superior-medial/inferior-lateral/inferior-medial) were evaluated in our study. Moreover, the following radiological data were analysed as well: bilaterality (unilateral/bilateral), distribution (intra-conal/extra-conal/intra- or extra-conal) and orbital structures affected (conal muscles, lacrimal gland, eyelid and optic nerve).

Ann Arbor classification was followed in our centre, thus, stage I (single orbit extralymphatic site) and low-grade tumours were treated by radiotherapy (overall dose of 35–40 Gy, in fractions of 2 Gy) for 1 month. Otherwise, aggressive subtype lymphoma or advanced stage (II, III or IV of Ann Arbor Criteria) combined with chemotherapy [10]. Radiological findings were reviewed regarding treatment response related to the size of orbital tumour during the follow-up. The following degrees of response were considered in the first check-up (after 6-12 months): complete response (disappearance of lesion), partial response (decrease of the size of the tumour of more than 50 % of the longest diameter), stable disease (decrease of less than 50 % or increase of less than 25 %) and progressive disease (increase of more than 25 %). Further follow-up exams were reviewed in some patients at time intervals of 1 year on average.

Results

The results are divided into the following items: patterns of involvement at diagnosis, follow-up and relapses.

Diagnosis

Quadrants

Regarding the number of affected quadrants, one quadrant was the main form (12/19, 63 %). Involvement of two (5/19, 26 %) and three quadrants (2/19, 11 %) were uncommon.

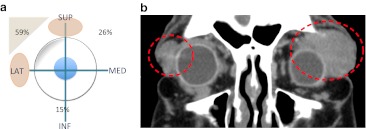

The most frequent location was the superior-lateral quadrant (11/19, 59 %). The superior-medial quadrant was involved secondary (5/19, 26 %). Inferior quadrants were unusual (3/19, 15 %) (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a This graph represents the lymphoma distribution at the diagnosis. The superior (SUP) and lateral (LAT) quadrant is the most common, medial (MED) and inferior (INF) quadrants are less affected. b Coronal reconstruction of contrast CT shows bilateral orbital lymphoma: two homogeneous masses are circled in both superior and lateral quadrants

Bilaterality

Most cases had unilateral involvement (18/19, 95 %) whereas bilateral affectation was exceptional (1/19, 5 %) (Fig. 1b).

Distribution

Based on the classical division of the orbit, the following spaces were considered: extra-conal compartment (outside the muscles cone) and intra-conal compartment (inside the muscles cone). Depending on this classification, the distribution of orbital lymphoma cases in order of frequency was: intra- and extra-conal (9/19, 47 %), extra-conal (8/19, 42 %) and intra-conal (2/19, 11 %).

Orbital structures

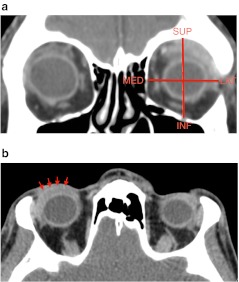

Regarding the orbital structures involved by lymphoma, the following results were found in descending order: superior rectus muscle (14/19, 74 %), lateral rectus muscle (11/19, 59 %), eyelid (10/19, 53 %) and lacrimal gland (9/19, 47 %). Some examples of these localisations are shown in Fig. 2. The remaining conal muscles were less frequently affected. Contact with optic nerve was reported in two cases.

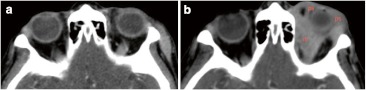

Fig. 2.

Contrast CT scans obtained in two different patients show typical pattern of orbital involvement by lymphoma. a There is superior and lateral rectus muscle as well as lacrimal gland involvement in a coronal reconstruction of CT. It is highlighted the predominant superior lateral quadrant involved. b CT after contrast shows a slight enhancement lesion within the eyelid (red arrows)

Other features

Other locations were described exceptionally in the literature, such as intracranial dural extension, which were not found in our study [7]. No tumoural calcification was observed in this review, nor involvement of bony structures. Although lymphoma can contact with bony orbital structures, no erosion or hyperostosis was noted. Similar behaviour within the eyeball has been described. Wide contact and even displacement of the globe have been observed, although no intraocular mass or infiltration signs were reported. Despite these features being observed in our images, radio-pathological correlation was not performed.

In addition, localisation of lymphoma is useful information when planning the appropriate surgical technique. For example, the management of adjacent structures, such as conal muscles, feeding vessels and nerves should determined. This information is helpful in order to avoid surgical complications.

Follow-up

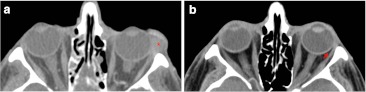

The assessment at first post-treatment follow-up exam was tabulated as follows: complete response (3/19, 15 %) (Fig. 3) and partial response (15/19, 80 %) (Fig. 4). Progressive imaging disease was observed in 1/19, 5 %, although satisfactory clinical response was seen before.

Fig. 3.

Contrast axial CT scans demonstrate complete lymphoma response after radiotherapy. a Well-defined mass (red asterisk) involves mainly the eyelid and the insertion of lateral rectus muscle. b First check 6 months after the diagnosis displays complete disappearance of tumour. Pay attention to the preserved fat tissue between the insertion of lateral rectus muscle and eyeball (red arrow)

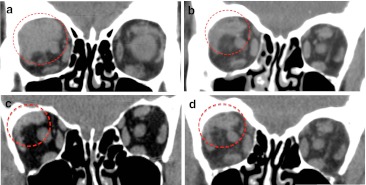

Fig. 4.

An example of a partial lymphoma response after treatment with residual images that remain stable on CT scans during the monitoring. a Homogeneous mass within superior-lateral quadrant is observed at diagnosis of lymphoma on non-contrasted CT. After treatment, marked reduction of the size is noted, although residual circled images keep stable in the following checks. b First contrasted CT after 8 months treatment. c, d Annual checks present no changes on non-contrasted CT

Further follow-up exams were performed every 12 months on average within a period from 1 to 5 years (mean, 2 years). Most subjects showed no changes, or even decreased size, of the residual images. However, relapses have been reported in two patients after 1 and 3 years, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Contrast CT scans show local relapse after response post-treatment of lymphoma. a First exam after 6 months post-treatment present positive response. b Although, second exam 12 months later presents an heterogeneous enhancing preseptal (ps) and retrobulbar (rb) mass in keeping with relapse

Discussion

Lymphoma diagnosis

In this study, we have found that lymphomas have a characteristic localisation in the orbit that can assist radiologists to orientate a proper diagnosis. This typical location consists of the involvement of superior quadrants; specifically, the superior-lateral one. The most commonly infiltrated structures are found within the superior-lateral quadrant, such as the superior rectus muscle, lateral rectus muscle, lacrimal gland and eyelid. Involvement of intra-conal space is usually associated with the extra-conal one, and is related with large size of the tumour. Therefore, an intra-conal involvement alone will not be the main pattern of lymphoma in the orbit. In addition, low prevalence is described within occupation of lower quadrants and contact with the optic nerve.

Differential diagnosis

These conclusions may help in the differential diagnosis of retrobulbar orbital mass-like lesions in adults. No globe tumours or childhood diseases are included. Classical distribution of intra/extra-conal spaces are used in the differential diagnosis as shown in Fig. 6 [11, 12]:

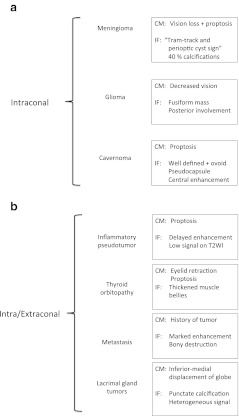

Fig. 6.

Intra-conal and intra/extra-conal mass-like lesions within adulthood are represented within this diagram. Main clinical manifestation (CM) and imaging findings (IF) are summarised. a First chart shows intra-conal mass-like lesions. b Second chart presents intra/extra-conal mass-like lesions

The most common intra-conal tumours are meningioma and glioma (Fig. 7). Optic nerve sheath meningioma is a solid, tubular, well-defined mass which presents uniform intense enhancement after contrast compared with the non-enhancing optic nerve (“tram-track sign” on axial images and “bull’s eye” on coronal images) [13, 14]. Around a third to a half display calcifications. Due to the characteristic encasement of meningioma it entails the well-known “perioptic cyst” between tumour and globe. Optic nerve glioma is frequently an aggressive subtype in adults. There is unilateral enlargement, moderate irregular enhancement and posterior extension. Bilateral low grade glioma associated with NF occurs most often in paediatric patients [15, 16].

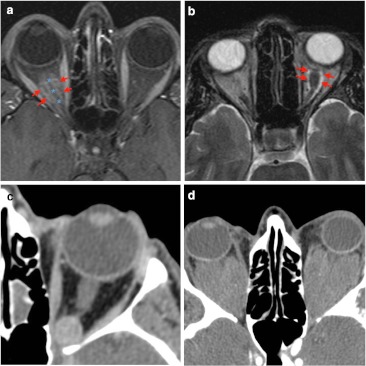

Fig. 7.

Examples of intra-conal mass-like lesions are given. a Fat-suppressed T1-weighted imaging shows tubular mass lesion which enhances intensively after contrast. On this axial image, the optic nerve (blue asterisk) appears as a negative defect in relation to the surrounding optic nerve sheath meningioma (red arrows), producing “the tram track sign”. b Optic glioma (red arrows) presents intra-conal mass and high signal intensity on axial T2-weighted imaging. This glioma is seen as a fusiform and well-defined lesion without intracranial extension. The patient presented a clinical history of vision loss. c Contrast CT scan presents an intra-conal well-defined round lesion. On venous phase CT shows homogeneous delayed enhancement in keeping with cavernous hemangioma. d Non-contrast CT scan shows bilateral homogeneous lesions in patient diagnosed of Erdheim-Chester disease. Typical location is intra-conal, so there is marked displacement of conal muscle due to the large size of the lesion

Cavernous haemangioma (or malformation) is commonly found as a well-defined intra-conal mass bounded by a fibrous pseudocapsule which manifests proptosis. High density can be identified due to microcalcification and may have low-intensity septation on T2-weighted imaging. Dynamic enhancement started from one point or portion and fills homogeneously on delayed images [17–20]. Another exceptional retrobulbar mass lesion might include Erdheim-Chester disease, which presents bilateral intra-conal masses associated with skeletal, retroperitoneal and pulmonary manifestations [21, 22].

The differential diagnosis for masses involving the intra- and extra-conal compartment should include (Fig. 8): inflammatory/metabolic disease (orbital inflammatory pseudotumour, thyroid orbitopathy, sarcoidosis) and neoplasm (lacrimal tumours, lymphoma and metastasis). Exceptional diseases—such as Sjögren, Wegener, and Kimura diseases—are just mentioned. Cystic retrobulbar lesions (such as dermoid and epidermoid cyst or mucocele) have different density (on CT) and intensity (on MRI) from soft tissue mass.

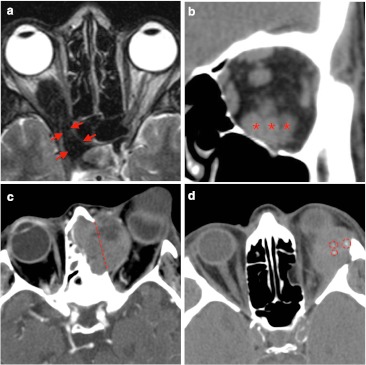

Fig. 8.

Common extra-conal mass-like lesions are shown: a There is marked hypointensity signal on T2-weighted imaging, which involves retrobulbar space and it seems to extend into orbital fissure (red arrows). These imaging findings were in keeping with pseudotumour inflammatory. b Patient with thyroid orbitopathy disease presented thickened muscles like the inferior rectus muscle (red asterisks). Prominent intra-conal fat was identified on this coronal reconstruction of non-contrast CT scan. c Metastatic melanoma shows a large mass with involvement of bony structures such as destruction of orbital plate of ethmoidal bone (dashed red line) and occupation of ethmoidal cells. Marked heterogeneous enhancement is seen on this axial contrasted CT scan. d Patient with exophthalmos and pathology diagnosis of lacrimal gland adenocarcinoma presents: ill-defined mass with medial and inferior displacement of the eyeball. Microcalcifications (red circled) are noted on non-contrast axial CT scan

Lymphoproliferative disease of the orbit is a spectrum of disorders that are included in this differential. All three entities mentioned before (lymphoid hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia and lymphoma) are challenging to differentiate by imaging, however, hyperplasia occupies mainly intra-conal space [7].

Inflammatory pseudotumours are often associated with fat tissue infiltration or oedema. Hypointense T2 signal is a helpful feature in order to differentiate from other tumours [23]. Extraorbital extension has been reported [24]. Variable contrast enhancement is described, although dual-phase contrasted CT reported an increased density on delayed images [8].

Thyroid orbitopathy consist in thickened muscles bellies over 4 mm. Common rectus muscles involved are inferior, medial, superior and lateral (mnemotecnics: “I’M SLow”). The tendinous insertion is usually not involved. Prominent intra-conal fat can also result in proptosis.

Sarcoidosis is a non-caseating granulomatous inflammation. Diffuse infiltration of orbital structures and dural thickening is identified [25, 26]. Finally, any malignant tumour may metastasise within the orbit. Characteristic finding may be hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging and heterogeneous enhancing mass. Bone destruction can occur [27, 28].

Lacrimal gland lesions can be classified into epithelial and non-epithelial. Epithelial tumours can be benign (pleomorphic adenoma) or malignant (pleomorphic adenocarcinoma). Carcinomas have heterogeneous signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images. Scalloped remodelling of bone structures and punctate calcification are occasionally identified [12].

Lymphoma follow-up

Radiological pattern after treatment can be helpful to the radiologist in monitored reports. Accordingly, 95 % of cases showed satisfactory response at first check post-treatment. Residual images were stable in most of the cases at the further follow-up. Previous studies [29–31] have also described some evidence of the high sensitivity of orbital to radiation therapy.

Although outstanding results have been achieved with radiotherapy, a balance against frequent treatment-related toxicities is needed. The most common toxicities consist of cutaneous and conjunctival reactions. Other long-term complications are cataract formation and xerophthalmia. High radiation dose may result in severe ophthalmological toxicity, such as ischaemic retinopathy, optic atrophy, corneal ulceration and neovascular glaucoma, associated with significant vision loss [32]. Therefore, although the recommended treatment is radiotherapy, there is no consensus on the optimal dose to be administered. New guidelines like the National Cancer Centre Network support low dose of radiotherapy at an early stage. Additional radiotherapy could be offered in recurrences [33]. Hence, these trends imply a relevant role of the radiological follow-up. The radiological evaluation should be as accurate as possible in order to detect orbital recurrences of lymphoma at an early stage. On the other hand, the radiation dose is essential information in monitoring.

Conclusion

This study provides a pattern of localisation of lymphoma which will be valuable for radiologists in the differential diagnosis of orbital masses. Combined CT and MRI can orientate a proper orbital mass diagnosis, although biopsy will still be required, imaging can help in this process too. It also offers a post-treatment guide of response after treatment which could be certainly beneficial in daily radiological practice. Some limitations should be considered in this study. First, most of our cases were evaluated by CT-scanning alone, with MRI being used in a low percentage of cases. We consider that multiplanar reconstruction and thin slice thickness by CT allows a correct localisation of lymphoma in orbit. Besides, intra-orbital fat provides natural contrast in CT exams, which achieves satisfactory differentiation of other structures. Furthermore, calcifications can be useful in the differential as well as the involvement of bony structures. Despite CT and MRI having a complementary role in the assessment of mass-like lesions in the orbit, MRI provides higher resolution in soft tissue evaluation. Moreover, recent development techniques such as marked thin slices and diffusion have an important value in the diagnosis and monitoring of lymphoma [9]. Due to this recent evidence and in order to avoid irradiation of the orbit, MRI will be the modality of choice, even if both techniques are available. Second, this is a retrospective study with a heterogeneous range of techniques used and periods of follow-up. Nevertheless, several cases and follow-up times were found, despite the low frequency of this disease, providing useful knowledge about this quite uncommon entity. Future research can be focused in the quadrants involved by the diverse orbital masses as well as the post-treatment monitoring depending on the dose of radiotherapy in lymphoma.

References

- 1.Bardenstein D. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: classification, clinical disease, and molecular biology. Ophthalmol Clin North. 2005;18:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjo LD, Ralfkiaer E, Prause JU, Petersen JH, Madsen J, Pedersen NT, Heegaard S. Increasing incidence of ophthalmic lymphoma in Denmark from 1980 to 2005. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3283–3288. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKelvie PA. Ocular adnexal lymphomas: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:251–261. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181e4abdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon PS, Juillard JF, Seich M, Parker G, Fu YS. Orbital lymphomas and pseudolymphomas: treatment with radiation therapy. Radiology. 1986;159:797–799. doi: 10.1148/radiology.159.3.3085143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rey-Porca C, Pérez-Encinas M, González F. Orbital lymphomas: presentation of nine cases. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2008;83:95–103. doi: 10.4321/S0365-66912008000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meunier J, Lumbroso L, Vincent-Salomon A, Dendale R, Asselain B, Arnaud P, Fourquet A, Desjardins L, Plancher C, Validire P, Chaoui D, Lévy C, Decaudin D. Ophthalmologic and intraocular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a large single centre study of initial characteristics, natural history and prognostic factors. Hematol Oncol. 2004;22:143–158. doi: 10.1002/hon.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akansel G, Hendrix L, Erickson BA, Demirci A, Papke A, Arslan A, Ciftci E. MRI patterns in orbital malignant lymphoma and atypical lymphocytic infiltrates. Eur J Radiol. 2005;53:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon WJ, Na DG, Ryoo JW, Kim MJ, Kim YD, Lim DH, Byun HS. Orbital lymphoma and subacute or chronic inflammatory pseudotumor: differentiation with two-phase helical computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:510–516. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Politi LS, Forghani R, Godi C, Resti AG, Ponzoni M, Bianchi S, Iadanza A, Ambrosi A, Falini A, Ferreri AJ, Curtin HD, Scotti G. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: diffusion-weighted MR imaging for differential diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. Radiology. 2010;256:565–574. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen V. Treatment options for ocular adnexal lymphoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:689–692. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S5828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemke AJ, Kazi I, Felix R. Magnetic resonance imaging of orbital tumors. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:2207–2219. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xian J, Zhang Z, Wang Z, Li J, Yang B, Man F, Chang Q, Zhang Y. Value of MR imaging in the differentiation of benign and malignant orbital tumors in adults. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1692–1702. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1711-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanamalla US. The optic nerve tram-track sign. Radiology. 2003;227:718–719. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2273010758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker M, Masterson K, Delavelle J, Viallon M, Vargas MI, Becker CD. Imaging of the optic nerve. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millar WS, Tartaglino LM, Sergott RC, Friedman DP, Flanders AE. MR of Malignant Optic Glioma of Adulthood. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1673–1676. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung EM, Specht CS, Schoeder JW. Pediatric orbit tumors and tumorlike lesions: neuroepithelial lesions of the ocular globe and optic nerve. Radiographics. 2007;27:1159–1186. doi: 10.1148/rg.274075014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilms G, Raat H, Dom R, Thywissen C, Demaerel P, Dralands G, Baert AL. Orbital cavernous hemangioma: findings on sequential Gd-enhanced MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:548–551. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199507000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorn-Kany M, Arrué DMB, Lacroix F, Lagarrigue J, Manelfe C. Cavernous hemangiomas of the orbit MR imaging. J Neuroradiol. 1999;26:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka A, Mihara F, Yoshiura T, Togao O, Kuwabara Y, Natori Y, Sasaki T, Honda H. Differentiation of cavernous hemangioma from Schwannoma of the orbit: a dynamic MRI study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1799–1804. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smoker W, Gentry L, Yee N, Reede D, Nerad J. Vascular lesions of the orbit: more than meets the eye. Radiographics. 2008;28:185–204. doi: 10.1148/rg.281075040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adem C, Helie O, Leveque C, Taillia H, Cordoliani YS. Case 78: Erdheim-Chester disease with central nervous system involvement. Radiology. 2005;234:111–115. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341021806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson MD, Aulino JP, Jagasia M, Mawn LA. Case report Erdheim-Chester disease mimicking multiple meningiomas síndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:134–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood S, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003;23:719–729. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee EJ, Jung SJ, Kim BS, Ahn KJ, Kim YJ, Jung AK, Park CS, Song SY, Park NH, Kim SM. MR Imaging of orbital inflammatory pseudotumors with extraorbital extension. Korean J Radiol. 2005;6:82–88. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2005.6.2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon EM, Zoarski GH, Rothman MI, Numaguchi Y, Zagardo MT, Mathis JM. Systemic sarcoidosis with bilateral orbital involvement: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:336–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mafee MF, Dorodi S, Pai E. Sarcoidosis of the eye, orbit and central nervous system. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:73–87. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotwald TF, Zinreich SJ, Schocke M, Frede T, Bellmann R, Nedden Z. CT and MR imaging of orbital metastasis from islet cell carcinoma of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:475–476. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.2.1750475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Char DH, Miller T, Kroll S. Orbital metastases: diagnosis and course. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:386–390. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.5.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decaudin D, Cremoux P, Vincent-Salomon A, Dendale R, Lumbroso L. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a review of clinicopathologic features and treatment options. Blood. 2006;108:1451–1460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayraktar S, Bayraktar U, Stefanovic A, Lossos IS. Primary ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT): single institution experience in a large cohort of patients. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, Wells W, Hodgson DC, Sun A, Crump M, Patterson BJ. Localized mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiation therapy has excellent clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2003;22:4157–4164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh AD. Clinical ophthalmic oncology. In: Damato BE, Pe’er J, Murphree AL, Perry JD, editors. Orbital and adnexal lymphoma (Orbital tumors) Philadephia: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 565–570. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefanovic A, Lossos I. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Blood. 2009;114:501–510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]