The authors report that giant hepatic cysts can be removed by single-access laparoscopy and curved reusable instruments.

Keywords: Liver cyst, Unroofing, Single-incision, Single-port, Single-site, Single-access, Laparoscopy

Abstract

Introduction:

Single-access laparoscopy has garnered growing interest in recent years in an attempt to improve cosmesis, reduce postoperative pain, and minimize abdominal wall trauma.

Case Description:

A female patient suffering from a symptomatic giant biliary cyst of the liver segments 4-7-8 was admitted for transumbilical single-access laparoscopic cyst unroofing. The procedure was performed using a standard 11-mm reusable trocar for a 10-mm, 30°- angled, rigid scope and curved reusable instruments inserted transumbilically without trocars. Operative time was 90 minutes, and the final incision length was 14 mm. The use of minimal pain medication permitted discharge on the third postoperative day, and after 25 months, the patient remains asymptomatic with a no visible umbilical scar.

Conclusions:

Giant biliary cysts can be removed by single-access laparoscopy. Because of this technique, surgeons work in ergonomic positions, and the cost of the procedure remains similar to that of the multitrocar technique. The incision length and the use of pain medication are kept minimal as well.

INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of laparoscopy, the removal of liver lesions using minimally invasive techniques had been reported to be feasible and safe.1–3 Because of laparoscopy, the postoperative pain, the hospital stay, and the abdominal trauma can be reduced, besides an improved comfort of the patient. Furthermore, the laparoscopic technique has also the advantage of minimal scarring and fewer adhesions, thereby increasing the feasibility of repeat liver resection.4

Single-incision, single-port, single-site, or single-access laparoscopy (SAL) has garnered growing interest in recent years, in an attempt to minimize the abdominal wall trauma, to reduce postoperative pain, and to overall improve the cosmetic outcomes.5

Nonparasitic liver cysts are usually asymptomatic, but abdominal pain due to their enlargement,6 physical signs such as obstructive jaundice,7 complications such as rupture8 or intracystic hemorrhage,9 can occur during follow-up. Hence, surgical treatment may be recommended mainly to relieve symptoms or to prevent potential complications. However, a relatively low rate of risk for recurrence has been reported.6,10–12 Preoperative consideration based on patient age, habitus, cystic size, aspect, and liver segment location is necessary.

Fenestration or unroofing nonparasitic cysts has been first described in open surgery in 196813 and by laparoscopy in 1991.14–15 Recently, because of the growing popularity of other minimally invasive techniques, SAL has been proposed. Cyst unroofing may be a good candidate for SAL because no sophisticated laparoscopic maneuvers, such as Pringle maneuver or hepatic vein clamps are necessary, rendering this procedure easier to be performed.

We report a SAL biliary cyst unroofing performed completely through the umbilicus, in a patient presenting with a symptomatic giant cyst of the liver segments 4-7-8.

CASE REPORT

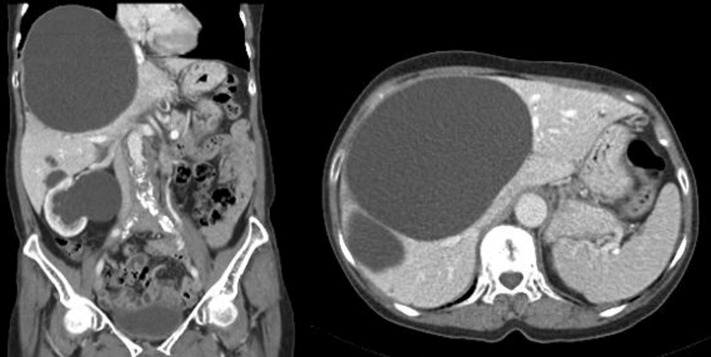

A 53-year-old female with a body mass index of 20.8 kg/m2 was referred for a symptomatic pain in the right upper quadrant. The patient had no history of previous surgery, and she was undergoing medical therapy for arterial hypertension. The chest X-ray showed a minimal elevation of the right diaphragmatic dome, and the abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a simple biliary cyst 15cm x 14cm in diameter in the apex of the liver segments 4-7-8, besides to polycystic liver and kidneys (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preoperative abdominal CT scan.

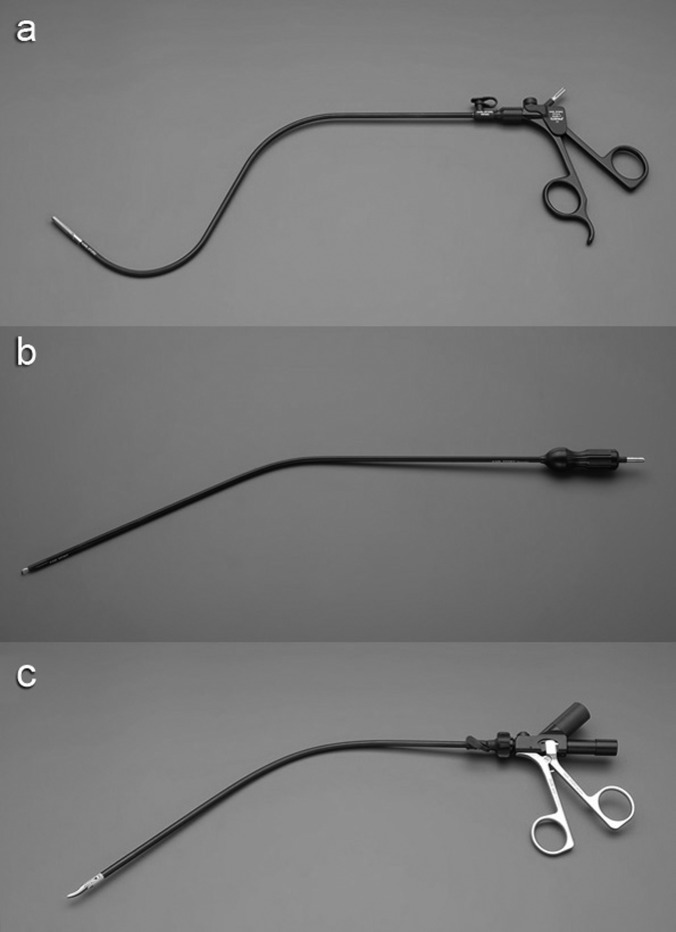

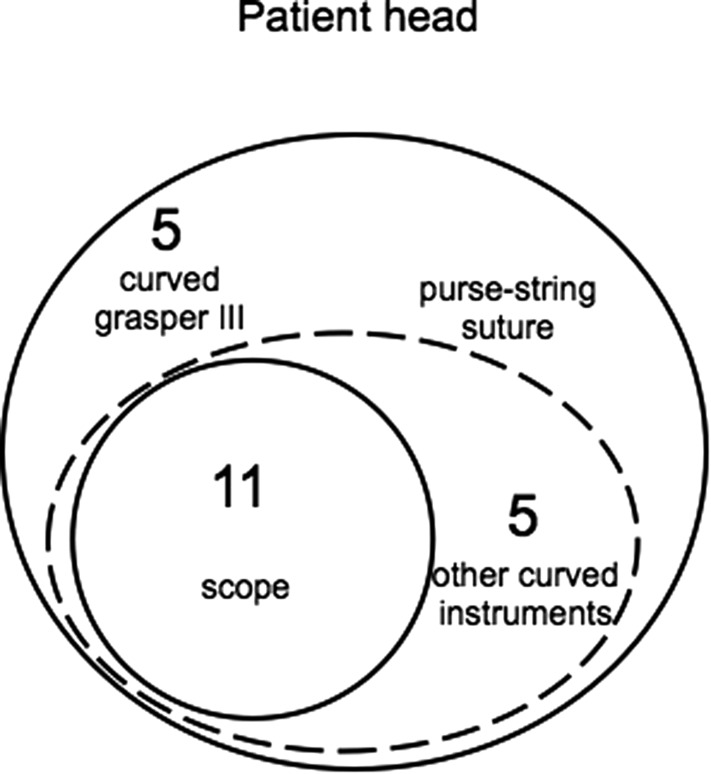

Transumbilical single-access laparoscopic giant biliary cyst unroofing was proposed to the patient. An incision in the umbilicus was realized, a 1-cm opening in the fascia was created, and a 1 polydiaxone (PDS) purse-string suture was placed in the fascia. An 11-mm reusable trocar was inserted inside the purse-string suture, and pneumoperitoneum was created. A 10-mm, 30°-angled, rigid, standard-length scope (Karl Storz-Endoskope, Tuttlingen, Germany), and curved reusable instruments (Karl Storz-Endoskope, Tuttlingen, Germany) were used. The curved instruments were advanced transumbilically without trocars. The curved grasping forceps III (Figure 2a), kept in the surgeon's nondominant hand, was inserted through a separate window outside the purse-string suture at the 10 o'clock position. The other curved instruments for the surgeon's dominant hand, such as the coagulating hook (Figure 2b), the bipolar scissors (Figure 2c), and the suction device, were inserted inside the purse-string suture and besides the 11-mm trocar at the 3 o'clock position (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

a, 2b, and 2c. Curved reusable instruments according to DAPRI: grasping forceps III (a), coagulating hook (b), bipolar scissors (c) (courtesy of Karl Storz-Endoskope, Tuttlingen, Germany).

Figure 3.

Placement of curved instruments, scope, and purse-string suture through the umbilical incision.

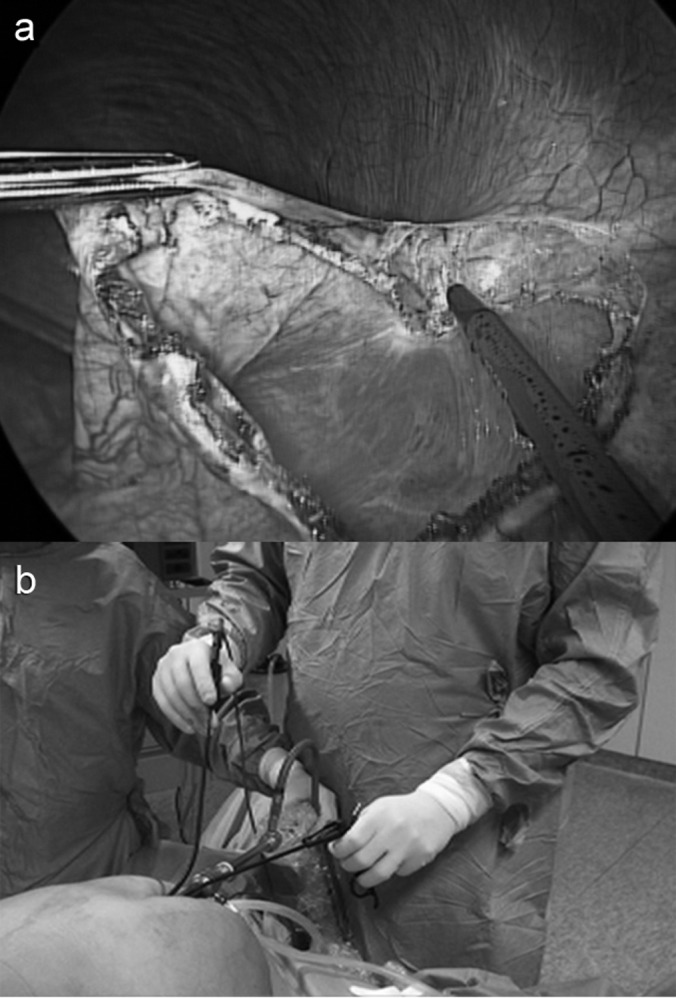

The cystic dome was identified and incised enough to empty the cystic cavity with the suction device. Because of this maneuver, a nonconnection between the biliary cyst and the biliary tree was evidenced. A complete excision of the cystic roof was performed using coagulating hook and bipolar scissors. Because of the curves of the instruments, the classic working triangulation during laparoscopy was established inside the abdomen, and surgeon was able to work in ergonomic positions during the entire procedure (Figures 4a and 4b). A custom-made plastic bag was introduced into the abdomen through the 11-mm trocar, and the tissue specimen was placed inside and removed transumbilically. The cystic cavity was finally checked for bleeding and was left open without an omental patch. The gallbladder was not removed, and the procedure ended with the removal of the instruments and trocar under view. A meticulous closure of the umbilical fascia and of the separate window for the grasper was performed, to avoid development of incisional hernia.

Figure 4.

a and 4b. Single-access cystic roof excision (a) performed under ergonomic position (b).

RESULTS

Total operative time (between skin incision and closure of the fascia) was 90 minutes, and laparoscopic time (between beginning of pneumoperitoneum and removal of the instruments and trocar) was 81 minutes. Blood loss was limited to 50mL and no additional trocars needed to be inserted. The final umbilical scar was 14mm in length. Pathological examination showed a benign, simple biliary cyst. Use of minimal pain medication permitted the discharge of the patient on the third postoperative day. After 25 months, the patient remains asymptomatic, without recurrence, and the umbilical scar is not visible.

DISCUSSION

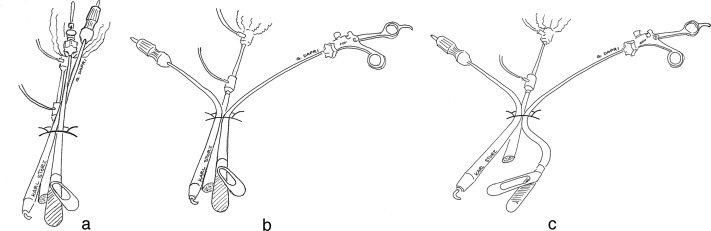

Laparoscopic surgery with the advent of SAL frequently bypasses one of its rules, which is working in triangulation with the scope at the bisector of this angle.16 An option for obtaining working triangulation inside the abdomen can be offered by the use of articulating instruments, which permit achieving this principle at the usual cost of the surgeon crossing either hands or the instruments' tips. Alternatively, the use of curved instruments can establish the classic laparoscopic working triangulation both internally and externally (Figure 5a, 5b, and 5c), and the surgeon maintains ergonomic positions.

Figure 5a, 5b, and 5c.

The concept of the curved instruments is based on the straight classic instruments (a) of the triangulation angle, both externally (b) and inside the abdominal cavity (c).

No specific ports and only 1 conventional reusable 11-mm trocar for the optical system and a transumbilical insertion of the instruments without trocars are used in this specific SAL technique. Thus, a technique to avoid loss of the pneumoperitoneum is adopted and consisted in the placement of a purse-string suture in the umbilical fascia and insertion of the instrument (eg, the grasper) for the surgeon's nondominant hand outside the suture, through a separate fascia window. The grasper is never changed during the entire procedure, whereas the other instruments for the surgeon's dominant hand (eg, the coagulating hook, bipolar scissors, and the suction device) are continuously changed. Hence, they are introduced inside the purse-string suture and alongside the 11-mm trocar. The purse-string suture is sufficiently tied to avoid loss of the pneumoperitoneum and opened only to allow the instruments to be changed, or to evacuate the smoke created during the dissection.

An 11-mm trocar is used because it allows the maintenance of pneumoperitoneum during the entire procedure and the use of a 10-mm 30°-angled scope. Another possibility is the use of a 5-mm flexible scope (EndoEye camera system, Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), which simultaneously permits an increase in the space between the hands of the cameraman and the surgeon outside of the access,17 but a remaining problematic factor is the concomitant reduction of the magnified quality of the image.

In the technique described here, the umbilical fascia opening for the 11-mm trocar and for the surgeon's dominant hand instruments allows the specimen to be removed without enlarging the opening or necessitating replacement by a larger trocar.17 Furthermore, because of this simple approach, the length of the umbilical scar remains similar to the incision realized for a conventional 12-mm trocar; otherwise, an increased incision length is required for the insertion of multiple trocars through the same incision17 or through the same port-device.5,18

Another advantage of the technique reported here is the cost of the procedure, which appears to be the same as multitrocar laparoscopy, because all of the materials utilized are reusable.

Here, we have reported a case that was feasible for transumbilical SAL, but appropriate selection based on patient age, habitus, cystic size, aspect, and liver segment location is necessary to decrease the incidence of additional trocars' insertion or the conversion to laparotomy. Obviously, if some perioperative complications occur, such as uncontrolled bleeding or biliary spillage, the insertion of 1 or more additional trocars is mandatory. The use of percutaneous stitches19 or introduction of millimetric wire are alternative options to help in the cystic dome retraction20 or operative field exposure.21

Technically, we emptied the cyst at the beginning of the procedure, permitting a precise resection of the cystic dome margin under simple tissue retraction by the grasper. We use to perform these types of liver resections by either coagulating hook or bipolar scissors also during multitrocar laparoscopy, hence we adopted the same strategy in SAL. However other instruments such as harmonic shears (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH)20,22 or a LigaSure device (Covidien New Haven, CT)17 can be used. In contrast to other authors,17 we did not place a transumbilical drain at the end of the procedure, to avoid possible umbilical incisional hernia formation during follow-up. If a drain has to be left in the cavity, better would be to make a second incision in the abdomen, which can also be used from the beginning of the procedure for an additional instrument (eg, needlescopic grasper).

We recorded a total operative time of 90 minutes, including the time needed to create the open access of the cavity, the placement of the purse-string suture in the fascia, and the final closure of this latter. Our operative time remains in the interval time reported in the literature during multitrocar laparoscopic liver cyst unroofing11,23 and comparable to the 60–100 minutes reported during SAL.5,17-18,20

Finally, we discharged the patient on the third postoperative day, which is 1 day earlier than that typically reported with other SALs.5,18

CONCLUSIONS

Giant biliary cysts can be removed by SAL. Because of the use of curved reusable instruments, the classic laparoscopic working triangulation is established inside the abdomen, and the surgeon works under external ergonomic positions. Due to this technique, the cost of the procedure remains similar to that of multitrocar laparoscopy, and the incision length with the use of pain medication are kept minimal as well.

Contributor Information

Giovanni Dapri, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, European School of Laparoscopic Surgery, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

Matteo Barabino, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, European School of Laparoscopic Surgery, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

Pietro Carnevali, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, European School of Laparoscopic Surgery, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

Ion Surdeanu, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, European School of Laparoscopic Surgery, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

Jacques Himpens, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, European School of Laparoscopic Surgery, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

Guy-Bernard Cadière, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, European School of Laparoscopic Surgery, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

Vincent Donckier, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Liver Unit, Erasme University Hospital, Brussels, Belgium..

References:

- 1. Cherqui D, Husson E, Hammoud R, et al. Laparoscopic liver resections: a feasibility study in 30 patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:753–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gigot JF, Glineur D, Azagra JS, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for malignant liver tumors. Ann Surg. 2002;236:90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Descottes B, Glineur D, Lachachi F, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection of benign liver tumors. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burpee SE, Kurian M, Murakame Y, Benevides S, Gagner M. The metabolic and immune response to laparoscopic versus open liver resection. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaujoux S, Kingham TP, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica MI, Allen PJ, Fong Y. Single-incision laparoscopic liver resection. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1489–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tagaya N, Nemoto T, Kubota K. Long-term results of laparoscopic unroofing of symptomatic solitary nonparasitic hepatic cysts. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Tamae T, et al. Treatments of non-parasitic giant hepatic cysts. Kurume Med J. 2001;48:193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mssrouri R, Chiche L. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic biliary cysts. J Chir. 2009;146:294–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takahashi G, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Bando K, Tajiri T. Intracystic hemorrhage of a large simple hepatic cyst. J Nippon Med Sch. 2008;75:302–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donati M, Stavrou GA, Wellmann A, Flemming P, Donati A, Oldhafer KJ. Laparoscopic deroofing of hepatic cysts: the most effective treatment option. Clin Ter. 2010;161:345–348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morino M, Garrone C, Festa V, Miglietta C. Laparoscopic treatment of non parasitic liver cysts. Ann Chir. 1996;50:419–425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Regev A, Reddy KR, Berho M, et al. Large cystic lesions of the liver in adults: a 15-year experience in a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin TY, Chen CC, Wang Sm. Treatment of non-parasitic cystic disease of the liver: a new approach to therapy with polycystic liver. Ann Surg. 1968;168:921–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paterson-Brown S, Garden OJ. Laser-assisted laparoscopic excision of liver cyst. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fabiani P, Katkhouda N, Iovine L, et al. Laparoscopic fenestration of biliary cysts. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:162–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanna GB, Drew T, Clinch P, Hunter B, Cuschieri A. Computer-controlled endoscopic performance assessment system. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:997–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shibao K, Higure A, Yamaguchi K. Case report: laparoendoscopic single-site fenestration of giant hepatic cyst. Surg Technol Int. 2010;20:133–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cai XJ, Zhu ZY, Liang X, et al. Single incision laparoscopic liver resection: a case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:2619–2620 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barbaros U, Sumer A, Tunca F, et al. Our early experiences with single-incision laparoscopic surgery: the first 32 patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sasaki K, Watanabe G, Matsuda M, Hashimoto M, Harano T. Original method of transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic deroofing for liver cyst. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:733–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobayashi S, Nagano H, Marubashi S, et al. A single-incision laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: initial experience in a Japanese patient. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:367–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weber T, Sendt W, Scheele J. Laparoscopic unroofing of nonparasitic liver cysts within segments VII and VIII: technical considerations. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palanivelu C, Jani K, Malladi V. Laparoscopic management of benign nonparasitic hepatic cysts: a prospective nonrandomized study. South Med J. 2006;99:1063–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]