This study supports the use of laparoscopic surgery for the elective removal of migrated intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCD) from within the peritoneal cavity.

Keywords: IUCD, IUD, Laparoscopic surgery, Systematic review

Abstract

Background:

Intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs) comprise the most popular form of reversible contraception. Uterine perforation is a rare but potentially serious complication associated with their use. We examined all reported cases of elective surgical removal of peritoneally migrated IUCDs, to compare laparoscopic and open approaches, and to identify beneficial surgical techniques.

Database:

MEDLINE and Embase were searched using the following medical subject heading terms: (IUCD or IUD or IUS or intrauterine device or intrauterine devices, copper or intrauterine devices, medicated) AND (migrated or displaced or foreign-body migration or intrauterine device migration) AND (peritoneal or peritoneal cavity). The Cochrane Library was searched using the terms IUCD, IUD, IUS, and intrauterine device. Additional studies were identified by manually searching the reference lists of the studies found through database search. Studies were included irrespective of language or publication type.

Discussion:

We identified 129 cases, reported in 30 studies. In the majority of cases (93.0% [120/129]), surgery was attempted laparoscopically; however 22.5% (27/120) of surgeries were converted to open operations, giving an overall rate of open surgery of 27.9% (36/129). This systematic review supports the use of laparoscopic surgery for elective removal of migrated IUCDs from the peritoneal cavity. With complications rarely reported, it is also likely the procedure could be undertaken in an outpatient setting. The use of intraoperative adjuncts (ie, cystoscopy) and the rate of conversion to open surgery are influenced by the site of the IUCD. Therefore, accurate preoperative localization of the device is advised.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs) are the most popular form of reversible contraception,1 with an estimated 175 million women using copper-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) or hormonal intrauterine systems (IUSs) in 2007.2

A rare but potentially serious complication of IUCD use is uterine perforation, with an incidence of 0.12 to 0.68 per 1000 insertions.3 The clinical presentation following perforation and migration is highly variable; many patients are asymptomatic and present with pregnancy or “missing strings.” A smaller number of patients present with acute symptoms of bowel obstruction4 or perforation.5

The standard management for a migrated IUCD is surgical removal, yet the rarity of migration means that for most surgeons, such a removal will be their first time encountering this clinical scenario. The aim of this review is to examine all reported cases of elective surgical removal of migrated IUCDs from within the peritoneal cavity—first, to compare laparoscopic and open approaches, and second, to identify any techniques that may benefit surgeons.

METHODS

The types of studies considered for this review included case reports and letters; review articles and guidelines were not included. Cases were included irrespective of the language of the article. Reported cases were included if elective surgery was undertaken, only where the IUCD was located within the peritoneal cavity; migrations to within the bladder, rectum, bowel, and retroperitoneum were excluded. Cases were included if the patient was either asymptomatic (including pregnancy) or with mild pain only; patients presenting acutely with peritonitis, obstruction, or intraabdominal abscess were excluded. Cases were included irrespective of patient age and parity, and even if they were published as part of a case series in which not all cases met the inclusion criteria.

Studies were identified by several methods: a search of the electronic databases MEDLINE (1948 to May 2011) and Embase (1947 to May 2011) was undertaken using the following search terms: (IUCD or IUD or IUS or intrauterine device or intrauterine devices, copper [medical search heading, MeSH, term] or intrauterine devices, medicated [MeSH term]) AND (migrated or displaced or foreign-body migration or foreign-body migration [MeSH term] or intrauterine device migration [MeSH term]) AND (peritoneal or peritoneal cavity [MeSH term]). The Cochrane Library was also searched using the following terms: IUCD, IUD, IUS, and intrauterine device. In addition, the reference lists of all studies found through the database search were hand searched and all potentially relevant studies were reviewed.

The titles and abstracts of all identified studies were screened; full-text articles were retrieved for all potentially relevant studies. Data were extracted from the included studies using a standardized data collection form, including the following items: country, type of study, year of surgery(s), and number of reported cases; and for each reported case: age, symptoms at presentation, whether surgery was undertaken, type of surgery, site of IUCD at retrieval, postoperative complications, any additional points of interest, and whether the case fulfils the inclusion criteria.

RESULTS

The electronic search of the MEDLINE and Embase databases identified 57 articles (when 11 duplicates were removed). A search of the Cochrane Library did not identify any relevant studies or reviews.

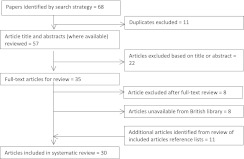

The review process is illustrated by a flow chart (Figure 1). The titles and abstracts of 57 articles were reviewed, and 22 articles were excluded at this stage. Full-text articles were therefore sought for the 35 studies thought to be relevant; 8 of these were not available either through online resources or from the British library. After full-text review, an additional 8 articles were excluded. The reference lists of all included studies were reviewed, which identified an additional 11 studies. A total of 30 studies were ultimately included (Table 1).6–10,12–36 Three of the included studies were not published in English, two in French, and one in German, and these were translated using online translation services.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review process.

Table 1.

Studies that met inclusion criteria for review (30 studies, 129 cases)

| Study | Country | Article Language | Type of Article | Number of Cases for Inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoni 199112 | Israel | English | Case series | 11 |

| Balci 20108 | Turkey | English | Retrospective study 2003–2008 | 18 |

| Brooks 197213 | United States | English | Case series | 4 |

| Demir 200214 | Turkey | English | Case series | 8 |

| Eke 200315 | Nigeria | English | Case series | 1 out of 5 reported |

| Haimov-Kochman 200316 | Israel | English | Case series | 8 |

| Heinberg 200817 | United States | English | Case series | 2 out of 3 reported |

| Koetsauvang 197318 | Thailand | English | Case report | 1 |

| Markovitch 200219 | Israel | English | Case series | 3 |

| Miranda 200320 | Italy | English | Case report | 1 |

| Mulayim 200621 | Turkey | English | Case report | 1 |

| Ozgun 200722 | Turkey | English | Case series | 9 out of 10 reported |

| Sun 200823 | Taiwan | English | Case report, letter | 1 |

| Robinson 197824 | United Kingdom | English | Case report, letter | 1 |

| Ikechecelu 200825 | Nigeria | English | Case report | 1 |

| Roberts 19726 | United States | English | Case report | 1 |

| Osborne 197826 | United Kingdom | English | Case series | 11 out of 13 reported |

| Gupta 198910 | India | English | Case series | 20 |

| Pont 200927 | France | French | Case report | 1 |

| Ferchiou 199528 | Tunisia | French | Case series | 8 out of 13 reported |

| Hepp 197729 | Germany | German | Case series | 2 out of 18 reported |

| Dunn 200230 | United States | English | Case report | 1 |

| Virkud 198931 | India | English | Case series | 3 |

| Mahmoud 20109 | United States | English | Case series | 3 |

| Sielgler 197332 | United States | English | Case series | 3 |

| Ratten 197133 | Australia | English | Case report | 1 |

| Tuncay 200434 | Turkey | English | Case series | 2 out of 6 reported |

| Olartecoechea 20097 | Spain | English | Case report (conference abstract) | 1 |

| Malik 199935 | India | English | Case report | 1 |

| Landowski 199036 | France | French | Case report | 1 |

Basic Characteristics of Cases

A total of 129 cases met the inclusion criteria, reported within 30 studies (Table 1).6–10,12–36 The mean age of reported cases was 28.8 years (among 107 cases where age was reported). Reported cases were from 14 different countries; the countries with most included cases were Turkey (29.5%), India (18.6%), Israel (17.1%), the United States (10.9%), and the United Kingdom (9.3%).

Types of IUCDs Used

The majority of IUCDs were copper-containing IUDs (64.3% [83/129]), the remainder were Lippes loop devices (17.8% [23/129]), or levonorgestrel-releasing devices (Mirena® 8.5% [11/129]); for 9.3% (12/129) of patients, the type of device was not reported.

Symptoms at Presentation

Almost half, 48.1% (62/129), of included patients were asymptomatic and had their missing IUCD discovered incidentally or following investigation due to an inability to locate the IUCD strings. Over a quarter (28.7% [37/129]) of patients were diagnosed as a result of pregnancy. Of the remainder, 17.8% (23/129) presented with pain, 4.7% (6/129) presented with irregular vaginal bleeding, and 1 patient, 0.8%, presented with chronic pelvic inflammatory disease.

Type of Surgery

In 93.0% (120/129) of patients, surgery was attempted laparoscopically; only 7.0% (9/129) were planned laparotomies. Of those attempted laparoscopically, 22.5% (27/120) were converted to open operations. Therefore overall, 27.9% (36/129) of patients required open surgery to remove their IUCD.

Site of IUCD at Time of Extraction

IUCDs were removed from multiple sites within the abdomen and pelvis (Table 2). We have categorized the cases into 3 groups according to location: First, 48.1% (62/129) were purely located among pelvic organs, and of these, the majority (42/62) were free within the pelvic area. Second, 46.5% (60/129) were located within the abdominal cavity and not related to pelvic organs; of these, most were embedded in the omentum or related to the bowel, with just 10% (6/60) being free within the abdomen. Last, a smaller group (5.4% [7/129]), involved both abdominal and pelvic organs.

Table 2.

Locations of IUCDs at time of extraction and the percentage requiring open surgery

| Site of IUCD at Time of Operation | n (%) | Rate of Open Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| All Sites | 129 | 36 (27.9%) |

| Pelvic location | 62 (48.1%) | 8 (12.9%) |

| Free in pelvis | 42 | |

| Attached to uterus | 9 | |

| Tubo-ovarian | 2 | |

| Attached to rectum | 3 | |

| Attached to bladder | 1 | |

| Attached to broad ligament | 5 | |

| Abdominal cavity, not related to pelvic organs | 60 (46.5%) | 24 (40.0%) |

| Embedded in omentum | 41 | |

| Free in peritoneal cavity | 6 | |

| Attached to bowel | 13 | |

| Involving abdominal and pelvic organs | 7 (5.4%) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Mass of bowel and pelvic structures | 4 | |

| Mass of omentum and pelvic structures | 3 |

Rate of Open Surgery According to Site of IUCD

The highest rate of open surgery was seen among patients having the IUCD related to both pelvic and abdominal organs (57.1% [4/7]). The lowest rate was seen among patients with their IUCDs confined to their pelvis and not affecting abdominal organs (12.9% [8/62]). The rate observed among those with an abdominal IUCD (not related to pelvic organs) was 40.0% (24/60).

Complications

Only 2 complications were reported; however, 11 studies did not comment on postoperative recovery. The 2 reported complications were an adhesive small bowel obstruction requiring reoperation at 2 weeks6 and fetal loss at 30 weeks, as this patient was inadvertently operated on while pregnant (day 26 of cycle).7

Additional Information

Two papers report the intraoperative use of fluoroscopy to aid in locating the migrated IUCD, which may have changed position since the time of preoperative imaging.8,9 Another paper reported the use of intraoperative cystoscopy and proctoscopy to ensure no bladder or rectal wall damage had occurred.10

DISCUSSION

Although a small number of patients with migrated IUCDs will present with acute symptoms necessitating urgent surgery, most will be relatively asymptomatic, and therefore undergo planned surgery. Despite most cases being asymptomatic, the current guidance is that all misplaced IUCDs should be surgically removed.11 We undertook this review with the aim of providing a comprehensive evaluation of the current evidence for those faced with this situation in their clinical practice. In particular, we aimed to determine whether laparoscopic surgery was an appropriate approach and to determine an approximate rate of conversion to open surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to address this issue and provides the most comprehensive review of the current evidence.

This review revealed that the majority (93.0%) of reported cases were attempted laparoscopically; however 22.5% of these were converted to open procedures. The overall rate of open surgery was found to vary according to the site of the misplaced IUCD. The patients with an IUCD that was related to both abdominal and pelvic organs had the highest rate of open surgery at 57.1%, compared with a rate of just 12.9% in those related to only pelvic organs and 40.0% in those related to only abdominal organs. These rates are likely to reflect the complexity of the surgery required to remove the IUCDs; because the majority of those located in the pelvis were “free” and not fixed to pelvic organs, it is not surprising that the rate of conversion was lowest among these cases.

A discussion regarding the risk of conversion to open surgery is an important part of the consent process for any laparoscopic surgery. This review provides surgeons with an approximate rate of conversion; however, it should be quoted with caution. The reported cases span the period from 1971 to 2010, during which significant advances in laparoscopic surgery have occurred. The inclusion of earlier cases may have led to the rate of conversion being falsely elevated. In addition, a review of case reports and retrospective case series will suffer significantly from publication bias, with novel and interesting cases, as well as those perceived to have been “successful” (ie, not converted) being preferentially published. However, despite these limitations, this report represents the best available evidence regarding the rate of conversion.

Very few complications were reported. Just 2 major complications were reported across the 129 cases included. This small number may also represent data likely to have suffered from publication bias, as in suppressed mention of those cases with complications. Additionally, there were 11 cases about which no comment on postoperative recovery was made. Despite these concerns, a laparoscopic approach appears to be safe, and would therefore be appropriate for this group of young patients, for whom cosmesis may be an important consideration. The infrequent number of complications and the age of this patient group studied indicate this surgery may be undertaken in an outpatient setting.

We did not evaluate the preoperative imaging used in each case. However, the site of the IUCD appears to influence the risk of conversion and the potential need for additional intraoperative procedures, such as cystoscopy and proctoscopy. Therefore, accurately locating the IUCD, with appropriate imaging, would ensure that the required equipment and specialists were present, as well as further informing the consent process.

In summary, the results of this systematic review support the use of laparoscopic surgery for the elective removal of migrated IUCDs from within the peritoneal cavity. With complications rarely being reported, it is also likely that the procedure could appropriately be undertaken in an outpatient setting. The intraoperative use of adjunct technology (such as cystoscopy) and the rate of open surgery are both influenced by the site of the IUCD; it is therefore advised that the device is accurately localized preoperatively.

Contributor Information

Frances R. Mosley, Department of General Surgery, Airedale General Hospital, Steeton, West Yorkshire, UK..

Navneel Shahi, Department of General Surgery, Airedale General Hospital, Steeton, West Yorkshire, UK..

Mohamed A. Kurer, Department of General Surgery, Airedale General Hospital, Steeton, West Yorkshire, UK..

References:

- 1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division World Contraceptive Use 2009. 2009. (POP/DB/CP/Rev2009) http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WCU2009/Main.html

- 2. Sivin I, Batár I. State-of-the-art of non-hormonal methods of contraception: III. Intrauterine devices. Eur J Contracept. 2010;15(2):96–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Broso PR, Buffetti G. The IUD and uterine perforation. Minerva Ginecol. 1994;46(9):505–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brar R, Doddi S, Ramasamy A, Sinha P. A forgotten migrated intrauterine contraceptive device is not always innocent: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2010. http://www.hindawi.com/journals/crim/2010/740642/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Bitterman A, Lefel O, Segev Y, Lavie O. Laparoscopic removal of an intrauterine device following colon perforation. JSLS. 2010;14(3):456–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roberts J, Ledger W. Operative removal of intraperitoneal intra-uterine contraceptive devices—a reappraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112:863–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olartecoechea B, Aub M, Garca Manero M. Migrated intrauterine device removal with laparoscopy in a pregnant woman. Gynecol Surg. 2009;6:S46 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Balci O, Mahmoud AS, Capar M, Colakoglu MC. Diagnosis and management of intra-abdominal, mislocated intrauterine devices. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(6):1019–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mahmoud MS, Merhi ZO. Computed tomography-assisted laparoscopic removal of intraabdominally migrated levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(4):627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gupta I, Sawhney H, Mahajan U. Laparoscopic removal of translocated intrauterine contraceptive devices. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;29:352–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organisation (WHO) Mechanism of action, safety and efficacy of intrauterine devices. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. WHO Technical Report Series. 1987;753:1–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adoni A, Ben Chetrit A. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brooks PG, Berci G, Lawrence A, Slipyan P, Wade ME. Removal of intra-abdominal intrauterine contraceptive devices through a peritoneoscope with the use of intraoperative fluoroscopy to aid localization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;113(1):104–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demir SC, Cetin MT, Ucunsak IF, Atay Y, Toksoz L, Kadayifci O. Removal of intra-abdominal intrauterine device by laparoscopy. Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care. 2002;7(1):20–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eke N, Okpani AO. Extrauterine translocated contraceptive device: a presentation of five cases and revisit of the enigmatic issues of iatrogenic perforation and migration. Afr J Reprod Health. 2003;7(3):117–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haimov-Kochman R, Doviner V, Amsalem H, Prus D, Adoni A, Lavy Y. Intraperitoneal levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device following uterine perforation: the role of progestins in adhesion formation. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):990–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heinberg E, McCoy T, Pasic R. The perforated intrauterine device: endoscopic retrieval. JSLS. 2008;12:97–100 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koetsauvang S. Laparascopic removal of a perforated copper-T IUD. A case report. Contraception. 1973;7(4):327–332 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Markovitch O, Klein Z, Gidoni Y, Holzinger M, Beyth Y. Extrauterine mislocated IUD: is surgical removal mandatory? Contraception. 2002;66(2):105–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miranda L, Settembre A, Capasso P, Cuccurullo D, Pisaniello D, Corcione F. Laparoscopic removal of an intraperitoneal translocated intrauterine contraceptive device. Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care. 2003;8(2):122–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mülayim B, Mülayim S, Celik NY. A lost intrauterine device. Guess where we found it and how it happened? Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care. 2006;11(1):47–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ozgun MT, Batukan C, Serin IS, Ozcelik B, Basbug M, Dolanbay M. Surgical management of intra-abdominal mislocated intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2007;75(2):96–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun C-C, Chang C-C, Yu M-H. Far-migrated intra-abdominal intrauterine device with abdominal pain. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;47(2):244–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robinson R. Copper intrauterine devices in the abdomen. Br J Med. 1978;2:1068–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ikechebelu JI, Mbamara SU. Laparoscopic retrieval of perforated intrauterine device. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11(4):394–395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Osborne J, Bennett M. Removal of intrabdominal intra-uterine device. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978;85:868–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pont M, Lantheaume S. Efficacite d'un sterilet au levonorgestrel migre en intra-abdominal. A propos d'un cas et revue de la litterature. [Abdominal migration of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Case report and review of the literature]. J Gynécol Obstét Biol Reprod. 2009;38(2):179–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferchiou M, Zhioua F, Hasnaoui M, Sghaier S, Jedoui A, Meriah S. Traitement coelio-chirurgical du sterilet intraperitoneal. [Laparoscopic surgery of an intraperitoneal intrauterine device.] Rev Fr Gynécol Obstét. 1995;90(10):409–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hepp H. Zum problem des “verlorenen” intrauterinpessars. [The problem of the lost intrauterine contraceptive device.] Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1977;37(8):653–659 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dunn J, Zerbe M, Bloomquist J, Ellerkman R, Bent A. Ectopic IUD complicating pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:57–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Virkud AM, Shah SK. Laparoscopic retrieval of transmigrated IUDS (report of 3 cases). J Postgrad Med. 1989;35(2):116–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Siegler AM. Removal of ectopic intrauterine contraceptive devices aided by laparoscopy. A report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;115(2):158–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ratten GJ. Removal of an intraperitoneal intrauterine device under laparoscopic control. Med J Aust. 1971;2(21):1077–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tuncay Y, Tuncay E, Guzin K, Ozturk D, Omurcan C, Yucel N. Transuterine migration as a complication of intrauterine contraceptive devices: Six case reports. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(3):194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malik P, Jameela B, Hameed F. Asymptomatic long standing iatrogenic abdominal foreign body - A rarity. JK Pract. 1999;6(2):150 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Landowski P, Cristalli B, Levardon M, de Joliniere J. Adhesion lysis and removal of an intraperitoneal contraceptive device by celioscopy. Rev Fr Gynécol Obstét . 1990;85(11):623–625 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]