Background: The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum utilizes PfEBA-140 to invade host erythrocytes.

Results: The minimal binding region of PfEBA-140 contains unique structural components compared with other Plasmodium invasion ligands.

Conclusion: Distinct structural and mechanistic elements of PfEBA-140 binding are likely determinants of receptor specificity.

Significance: This study provides the first view into the basis of receptor specificity of P. falciparum invasion ligands.

Keywords: Adhesion, Crystal Structure, Glycobiology, Malaria, Microbial Pathogenesis, Protein Structure, Receptors, X-ray Scattering, BAEBL, PfEBA-140

Abstract

Erythrocyte-binding antigen 140 (PfEBA-140) is a critical Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion ligand that engages glycophorin C on host erythrocytes during malaria infection. The minimal receptor-binding region of PfEBA-140 contains two conserved Duffy binding-like (DBL) domains, a fold unique to Plasmodium species. Here, we present the crystal structure of the receptor-binding region of PfEBA-140 at 2.4 Å resolution. The two-domain binding region is present as a monomer in the asymmetric unit, and the structure reveals novel features in PfEBA-140 that are likely determinants of receptor specificity. Analysis by small-angle x-ray scattering demonstrated that the minimal binding region is monomeric in solution, consistent with the crystal structure. Erythrocyte binding assays showed that the full-length binding region containing the tandem DBL domains is required for erythrocyte engagement, suggesting that both domains contain critical receptor contact sites. The electrostatic surface of PfEBA-140 elucidates a basic patch that constitutes a putative high-affinity binding interface spanning both DBL domains. Mutation of residues within this interface results in severely diminished erythrocyte binding. This study provides insight into the structural basis and mechanism of PfEBA-140 receptor engagement and forms a basis for future studies of this critical interaction. In addition, the solution and crystal structures allow the first identification of likely determinants of erythrocyte receptor specificity for P. falciparum invasion ligands. A complete understanding of the PfEBA-140 erythrocyte invasion pathway will aid in the design of invasion inhibitory therapeutics and vaccines.

Introduction

Erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium species is mediated by integral membrane proteins of the erythrocyte-binding ligand (EBL)3 family. During invasion, EBL proteins bind irreversibly and specifically to erythrocyte receptors to create a tight junction between host and parasite membranes. This interaction facilitates merozoite entry into the red blood cell. Plasmodium falciparum has a sophisticated invasion machinery with several EBL proteins that each bind a different erythrocyte receptor in a sialic acid-dependent manner (1). Erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 (PfEBA-175), erythrocyte-binding ligand 1 (PfEBL-1), and erythrocyte-binding antigen 140 (PfEBA-140) bind glycophorins A, B, and C, respectively (2–4). A fourth member of this family, erythrocyte-binding antigen 181 (PfEBA-181), binds an unknown receptor (5). The EBL family members are composed of two cysteine-rich regions designated region II (RII) and region VI and contain a type I transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic domain (6). Receptor binding has been localized to RII for all members. In the P. falciparum EBL family, this region contains two tandem Duffy binding-like (DBL) domains, F1 and F2. The DBL protein fold is unique to Plasmodium and is able to recognize and tightly bind a diverse array of host cell receptors. In addition to their critical role during invasion, DBL domains also mediate microvasculature adherence of infected erythrocytes by erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), a phenomenon directly associated with severe malaria (7).

It is unknown how the EBL proteins utilize such a highly conserved domain structure to recognize different erythrocyte receptors and thus provide P. falciparum with multiple pathways for invasion. In addition, the role of each individual erythrocyte invasion pathway during natural infection is not fully understood. However, it has been observed that Gerbich negativity is present at high frequency in regions of Papau New Guinea where infection with P. falciparum malaria is common (8). Gerbich-negative individuals have a deletion of exon 3 in the glycophorin C (GPC) gene that prevents PfEBA-140 erythrocyte binding and invasion. This observation provides strong evidence that severe malaria has selected for this mutation and illustrates the significance of erythrocyte invasion mediated by PfEBA-140.

As the tandem DBL domains in RII of the four P. falciparum EBL proteins can independently bind erythrocytes, they are the focus of combinatorial vaccine efforts. To understand how P. falciparum uses the DBL protein fold to recognize different erythrocyte receptors during invasion, we determined the crystal structure and examined the erythrocyte binding profile of RII PfEBA-140. In addition, the solution structure and oligomeric state of this invasion ligand were examined using small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS). The results presented here elucidate likely determinants of receptor specificity within the EBL family and provide insight into the structural basis of erythrocyte binding by the critical invasion ligand PfEBA-140.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

A codon-optimized construct containing amino acids 143–740 of RII PfEBA-140 with three point mutations (S303A, T469A, and S727A) was cloned for expression. The three mutations were introduced to avoid aberrant glycosylation at putative N-glycosylation sites during expression in mammalian cells that could otherwise impact protein homogeneity. This construct provided high yields of pure protein from Escherichia coli and was thus used for crystallization. These amino acid changes did not affect protein function, as demonstrated by erythrocyte binding assays described below. The construct was expressed as inclusion bodies in E. coli and recovered using 6 m guanidinium chloride. Following recovery, denatured protein (100 mg/liter) was rapidly diluted in 50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mm EDTA, 200 mm arginine, 0.1 mm PMSF, 2 mm reduced glutathione, and 0.2 mm oxidized glutathione. After 48 h of refolding at 4 °C, RII PfEBA-140 was concentrated using Amicon centrifugal filters and purified by size exclusion and ion exchange chromatography.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

Crystals were grown using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1μl of protein at 7.5 mg/ml with 1μl of reservoir containing 20% PEG 8000 and 0.1 m HEPES (pH 7.5). Initial crystal hits observed in precipitant screens (Qiagen) were used as seeds to optimize crystal growth. Seeds were generated by transferring the entire crystal drop into 10 μl of 20% PEG 8000 and 0.1 m HEPES (pH 7.5) and vortexing the sample. Crystals were sent for remote data collection at beamline 4.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Cryoprotectant composed of 30% glycerol, 17.5% PEG 8000, and 0.1 m HEPES (pH 7.5) was introduced gradually into the drop by pipetting. Crystals were isolated with nylon loops and stream-frozen prior to transport.

The RII PfEBA-140 structure was solved by molecular replacement using RII PfEBA-175 as a model in BALBES (9). Automated refinement was performed with PHENIX (10), and manual model building was performed with Coot (11). Refinement was completed once low R-factors and good geometry were obtained (see Table 1). The structure described has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 4GF2.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

Values in parentheses are for highest resolution shell. r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

| RII PfEBA-140 | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 65.42, 76.48, 82.34 |

| α, β, γ | 90.00°, 96.80°, 90.00° |

| Resolution (Å) | 20–2.4 (2.49–2.40) |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.8 (78.9) |

| I/σI | 19.06 (2.07) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.4 (98.0) |

| Redundancy | 3.72 (3.67) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0–2.4 |

| No. of reflections | 31,507 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 20.03/23.69 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 5339 |

| Ligand/ion | 90 |

| Water | 143 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 67.57 |

| Ligand/ion | 78.16 |

| Water | 53.73 |

| r.m.s.d. | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 |

| Bond angles | 0.607° |

| Ramachandran (%) | |

| Favored | 97.46 |

| Allowed | 2.54 |

| Disallowed | 0.00 |

SAXS

SAXS data were collected at SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source using standard procedures. 30 μl of RII PfEBA-140 at 1 mg/ml was automatically loaded into the cuvette with a Hamilton syringe robot (12). Radiation damage was assessed by overlaying short exposures using PRIMUS (13). CRYSOL (14) was used to compare experimental profiles with the crystal structure, and DAMMIF was used for ab initio model generation (15). Structures and SAXS reconstructions were aligned using SUPCOMB20 (16).

Erythrocyte Binding Assay

RII PfEBA-140 containing the three mutations (S303A, T469A, and S727A) was fused to C-terminal GFP and cloned into pRE4 for surface expression on HEK-293T cells. Monolayers of HEK-293T cells grown in 3.5-cm wells were transfected with 2.7 μg of plasmid DNA in polyethyleneimine. The erythrocyte binding assay was performed 20 h after transfection. Transfected cells were incubated with normal human erythrocytes at 2% hematocrit for 2 h. Following incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS. In each experiment, three individual wells of HEK-293T cells were transfected with each construct. Binding phenotypes were assessed for 10 fields of view from each of the three wells of transfected cells (for a total of 30 images for each construct).

RESULTS

Overall Structure of RII PfEBA-140

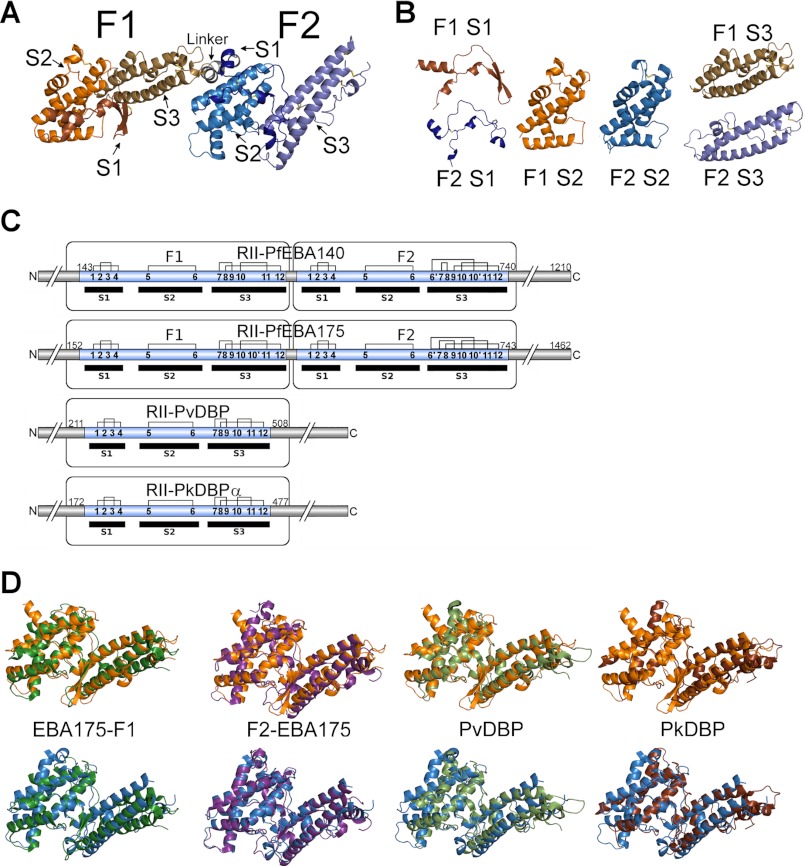

To define the structural basis of PfEBA-140 receptor specificity, we solved the crystal structure of RII PfEBA-140 (Fig. 1A and Table 1). RII PfEBA-140 is present as a monomer in the asymmetric unit, and no oligomeric contacts with potential physiological relevance are observed (Fig. 1A). The two DBL domains, F1 (residues 143–422) and F2 (residues 447–740), are connected by a short helical linker. Each DBL domain is composed of three subdomains (Fig. 1B) and contains a unique disulfide bridge pattern relative to other DBL family members (Fig. 1C). The F1 and F2 domains of PfEBA-140 are structurally similar to other DBL domains of Plasmodium invasion ligands (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Structure of RII PfEBA-140. A, overall structure of RII PfEBA-140 as well as the location of individual subdomains within each DBL domain. F1 subdomain 1 is shown in bronze, subdomain 2 in orange, and subdomain 3 in dark orange. F2 subdomain 1 is shown in dark blue, subdomain 2 in blue, and subdomain 3 in light blue. The short helical linker between the two domains is shown in gray. B, structures of the individual subdomains in RII PfEBA-140. Coloring is the same as described for A. C, representation of the disulfide bridge pattern of characterized EBL ligands displaying the two altered disulfides in RII PfEBA-140. D, overlay of Plasmodium invasion ligand DBL domains with each DBL domain of RII PfEBA-140. F1 PfEBA-140 in shown in orange (upper), and F2 PfEBA-140 is shown in blue (lower). F1 PfEBA-175 is shown in dark green, F2 PfEBA-175 in purple, PvDBP in light green, and PkDBP in brown.

PfEBA-140 Erythrocyte Binding Requires Both DBL Domains

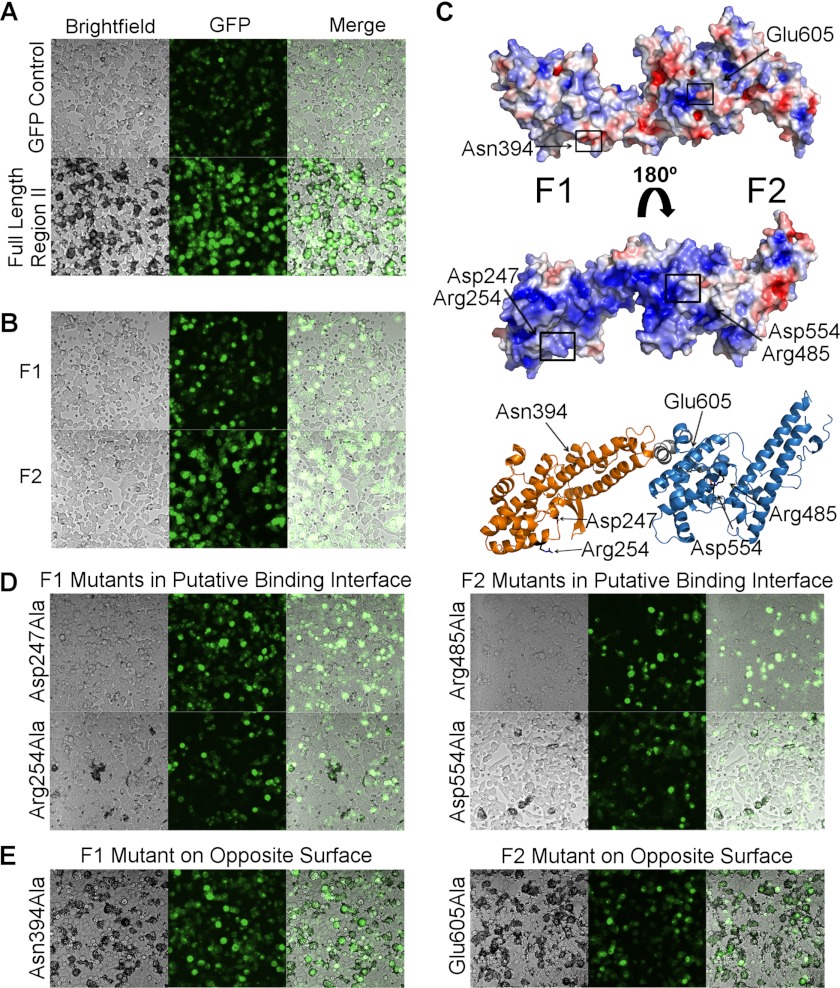

The presence of two structurally conserved domains within the minimal binding region suggests that each domain may be able to independently engage erythrocytes. To assess the function of the individual DBL domains, full-length RII PfEBA-140 and constructs containing each individual DBL domain were tested for erythrocyte binding by rosetting assay. Full-length RII PfEBA-140, corresponding to the construct used for crystallization, bound extensively to erythrocytes (Fig. 2A). In contrast, neither DBL domain was capable of independently engaging erythrocytes (Fig. 2B), suggesting that both domains make essential contacts with GPC during invasion. This result is supported by examination of the electrostatic surface of RII PfEBA-140, which elucidates a putative high-affinity binding interface (Fig. 2C). This region forms an arch of overall positive charge that spans the two DBL domains and would provide an ideal interaction surface for engagement of the highly glycosylated, acidic GPC.

FIGURE 2.

PfEBA-140 erythrocyte binding requires both DBL domains. A, RII PfEBA-140 was expressed on the surface of HEK-293 mammalian cells and tested for erythrocyte binding. GFP was utilized to assess proper surface expression. A construct expressing only GFP did not bind erythrocytes (upper panel). The full-length RII construct, identical to the construct used for crystallization, was capable of extensively engaging erythrocytes (lower panel). Bound erythrocytes appear black around the mammalian cells. B, the individual DBL domains of PfEBA-140 were also tested for erythrocyte binding. The F1 (upper panel) and F2 (lower panel) DBL domains could not independently engage erythrocytes. C, the electrostatic surface of PfEBA-140 RII elucidates a putative high-affinity binding interface. The surface of the protein shown in the upper panel has no clear region of concentrated charged residues (blue, positive charge; red, negative charge). However, when rotated 180°, a region of positive charge that forms an arch between the two DBL domains is illuminated (middle panel). Surface charge potential is colored from +3.5 to −3.5 eV. The lower panel displays the face of the protein-containing the basic patch identified as a putative binding interface. Residues mutated to alanine and tested for erythrocyte binding are identified with arrows and shown in black. D, alanine mutations within the basic patch disrupted erythrocyte binding. E, in contrast to residues within the basic patch, alanine mutations on the opposite face of RII PfEBA-140 did not disrupt erythrocyte binding.

To assess the functional importance of the putative binding interface, individual amino acid residues within the basic patch were mutated to alanine and tested for deficient erythrocyte binding. Large polar and/or charged residues are often involved in glycoprotein interactions; thus, we focused on these residues for testing (Fig. 2C). Four residues were identified that, when mutated to alanine, resulted in greatly diminished or null erythrocyte binding (Fig. 2D). This result confirms the vital role of individual residues within the putative interface during receptor binding. To test the alternate side of the protein, residues on the face opposite of the basic patch were also mutated to alanine. Mutation of these residues had no effect on binding, supporting the specific functional role of residues within the basic interface (Fig. 2E).

Structural Basis of PfEBA-140 Receptor Specificity

Unique structural elements distinguish RII PfEBA-140 from other DBL domain-containing EBL ligands and are the likely basis of receptor specificity. All 26 cysteines in RII PfEBA-140 are involved in disulfide bonds, and two of the disulfide linkages are distinct from other characterized DBL domains (Fig. 1C). The modified disulfide pattern includes a linkage between Cys-7 and Cys-8, as well as a linkage between Cys-9 and Cys-12. In contrast, linkages between Cys-7 and Cys-9 and between Cys-8 and Cys-12 are observed in all other characterized EBL members.

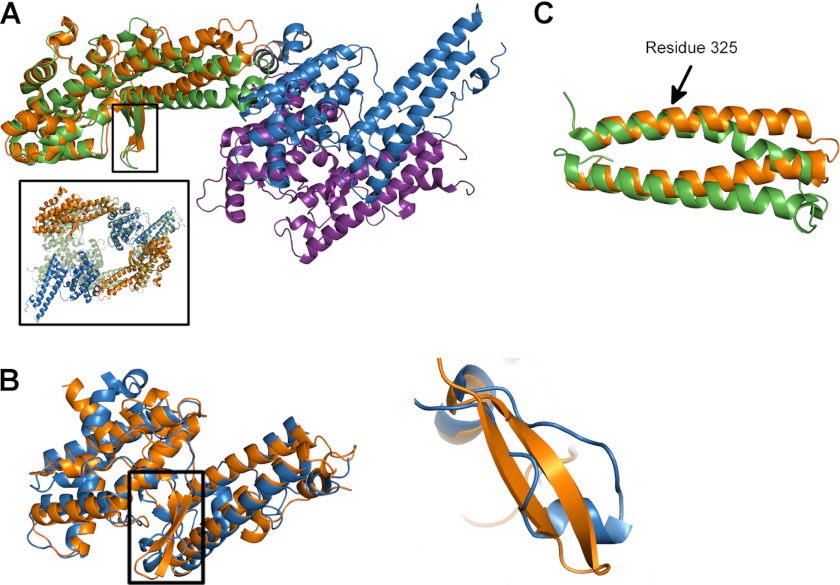

In addition to an altered disulfide pattern, several elements of the RII PfEBA-140 subdomain structure are unique among DBL domains. In RII PfEBA-175, β-fingers present in both DBL domains contain long loops that serve as critical dimeric contacts required for receptor binding (17). In contrast, Plasmodium vivax Duffy-binding protein (PvDBP) and Plasmodium knowlesi Duffy-binding protein (PkDBP), which contain only a single DBL domain in their RII, possess short loops within the β-finger region that do not seem to be important for the function of these ligands (18, 19). The β-finger of F1 PfEBA-140 is similar in length to the β-fingers of the PfEBA-175 F1 and F2 domains. In addition, the F1 β-fingers of PfEBA-140 and PfEBA-175 overlay quite well (Fig. 3A). However, the canonical β-finger motif in F1 PfEBA-140 is replaced with a novel αhelical segment in the F2 domain (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Structural determinants of receptor specificity within the EBL family. A, overlay of PfEBA-140 (with the F1 domain in orange and the F2 domain in blue) with PfEBA-175 (with the F1 domain in green and the F2 domain in purple). The conserved F1 β-sheet motifs are boxed. The inset displays two monomers of PfEBA-140 overlaid onto the PfEBA-175 dimer observed in the crystal structure (17). B, overlay of the F1 and F2 PfEBA-140 DBL domains (left panel). The altered helical element in F2 is boxed in black. A close-up view of this F2 helical element overlaid onto the F1 β-sheet is shown (right panel). C, view of the altered helical orientation of F1 RII PfEBA-140 subdomain 3 (orange). This orientation occurs due to the absence of a glycine, which is conserved in other EBL members, at residue 325 in PfEBA-140. The kink observed in F1 PfEBA-175 (green) is shown for comparison.

A third critical difference is the orientation of subdomain 3 in F1 PfEBA-140 with respect to the rest of the DBL domain. In most DBL domains, subdomain 3 contains a kink in a long helix facilitated by a glycine residue (Gly-185 in F1 PfEBA-175, Gly-490 in F2 PfEBA-175, Gly-397 in PvDBP, Gly-394 in PkDBP-α, and Gly-627 in F2 PfEBA-140). This glycine is absent in F1 PfEBA-140, and without the inherent flexibility of this residue, the kink in subdomain 3 cannot form. The absence of this kink leads to a drastic change within the subdomain that propagates through RII PfEBA-140, resulting in a large difference in the hinge angle between the two DBL domains compared with RII PfEBA-175 (Fig. 3, A and C). The splayed-out DBL domains of RII PfEBA-140 would require a large hinge movement to create the mode of dimerization seen in the crystal structure of RII PfEBA-175 (Fig. 3A, inset).

Solution Structure of PfEBA-140

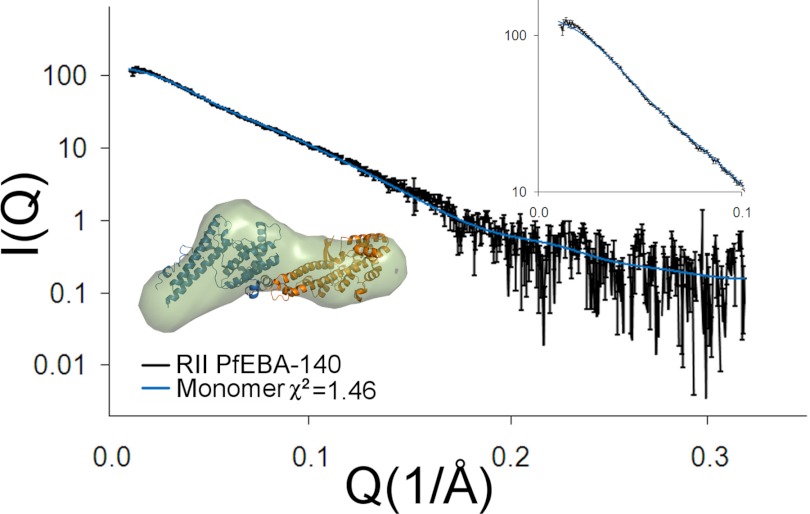

The structure and oligomeric state of parasite ligands in solution are important determinants of function. Both the related ligands PvDBP and PfEBA-175 appear to bind receptors as dimers (17, 18). We determined the solution structure and oligomeric state of RII PfEBA-140 by SAXS. The theoretical scatter for the monomeric PfEBA-140 crystal structure resulted in an excellent fit to the experimental SAXS profile, with a χ2 of 1.46 (Fig. 4). Furthermore, an averaged ab initio reconstruction revealed a molecular envelope that closely resembles the monomeric structure. This result is consistent with the observed crystal contacts and hinge angle between the F1 and F2 domains, suggesting that RII PfEBA-140 is monomeric in solution (Fig. 4). Only monomeric forms of PfEBA-140 have been described here, and there is no evidence for higher order oligomeric states in the absence of GPC.

FIGURE 4.

Oligomeric state of RII PfEBA-140. RII PfEBA-140 is monomeric in solution in the absence of receptor. Shown here are the experimental and theoretical SAXS plots of scattering intensity versus scattering momentum. The inset displays an ab initio construct of PfEBA-140 (light blue) overlaid onto the crystal structure (with the F1 domain in orange and the F2 domain in blue).

DISCUSSION

P. falciparum field isolates from endemic malaria regions actively utilize multiple erythrocyte invasion ligands, exemplifying the need to characterize each individual pathway (20). Antibodies targeting PfEBA-140 are capable of inhibiting invasion, supporting the critical role of this ligand during invasion (21). Furthermore, PfEBA-140 is naturally immunogenic. Serum isolated from patients infected with P. falciparum malaria is reactive to PfEBA-140, and RII was found to be the most immunoreactive element (22). The active immune response to PfEBA-140 provides strong support for its validity as a component of a combinatorial vaccine targeting invasion ligands. The structure described here forms a framework for future studies of the critical interaction between PfEBA-140 and erythrocytes. In addition, identifying the structural basis of receptor specificity within the EBL family is essential to characterizing the full range of invasion pathways utilized by P. falciparum. These results will thus aid in the rational development of invasion inhibitory therapeutics and vaccines.

The structural differences identified in RII PfEBA-140 suggest an altered mechanism of binding relative to PfEBA-175 and likely other EBL members. It has been proposed that dimerization is an important mechanistic component of EBL-mediated invasion. Support for this proposed mechanism comes from the fact that PvDBP is monomeric in the absence of receptor and dimerizes upon binding its receptor, DARC (18). In addition, PfEBA-175 crystallizes as a dimer and may engage GPA in the dimeric form observed in the crystal structure (17). It is possible that PfEBA-140 follows this EBL pattern and engages GPC as a dimer while existing as a monomer in the absence of receptor. However, to bind GPC using the dimer architecture observed for PfEBA-175, RII PfEBA-140 would need to undergo a large structural hinge movement and display dimeric contacts not observed in PfEBA-175. Specifically, the β-finger motifs in each DBL domain of PfEBA-175 make dimeric contacts. The presence of a unique helical element in place of the canonical β-finger motif in F2 PfEBA-140 may alter the dimeric contacts observed in PfEBA-175, resulting in a novel dimer conformation of PfEBA-140. It is equally possible that PfEBA-140 engages GPC as a monomer and that oligomeric state is an important determinant of receptor specificity.

Receptor recognition by PfEBA-140 is poorly understood; however, it is known that PfEBA-140 erythrocyte engagement is dependent on GPC glycans as well as the protein backbone. The proposed binding interface identified in the crystal structure spans both DBL domains (Fig. 2C). We demonstrated that both domains are required for erythrocyte binding and that mutating individual residues in each domain severely diminishes erythrocyte binding. These results suggest that each DBL domain forms essential contacts with GPC during invasion. In addition, the identification of the positive interface forms a basis for identifying the GPC-binding site. It is probable that vital receptor-binding interactions are located in this putative binding interface due to the concentrated presence of basic residues. The only known essential binding component on GPC is a solitary N-linked glycan at residue 8 (23). Putative O-linked glycans are abundant on GPC, but their role in binding has not been examined in detail. The critical N-linked glycan may make contacts with both DBL domains, explaining the requirement for full-length RII during binding. Alternatively, the N-linked glycan may bind with high specificity to one domain, whereas O-linked glycans and the protein backbone form essential contacts with the other domain. Further studies examining the interaction of RII PfEBA-140 with GPC are required to fully understand the structural and mechanistic basis of receptor recognition during invasion. In conclusion, we have provided insight into the PfEBA-140 binding mechanism, elucidated an important receptor-binding interface, and identified unique structural motifs in RII PfEBA-140 that form the basis of receptor specificity within the EBL family that allows P. falciparum to engage multiple host receptors during invasion.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Salinas and W. Beatty for assistance with experiments, D. Sibley for constructive comments on the manuscript, and J. Nix (Molecular Biology Consortium Beamline 4.2.2, Advanced Light Source) for help with data collection. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. We thank G. Hura, K. Dyer, and the Structurally Integrated Biology for Life Sciences Team at the Advanced Light Source for assistance in SAXS data collection (funded by Department of Energy IDAT Grant DE-AC02-05CH11231).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI 080792. This work was also supported by the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation (to N. H. T.) and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1143954 (to B. M. M.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4GF2) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- EBL

- erythrocyte-binding ligand

- Pf

- P. falciparum

- EBA

- erythrocyte-binding antigen

- RII

- region II

- DBL

- Duffy binding-like

- GPC

- glycophorin C

- SAXS

- small-angle x-ray scattering

- PvDBP

- P. vivax Duffy-binding protein

- PkDBP

- P. knowlesi Duffy-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cowman A. F., Crabb B. S. (2006) Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 124, 755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayer D. C., Cofie J., Jiang L., Hartl D. L., Tracy E., Kabat J., Mendoza L. H., Miller L. H. (2009) Glycophorin B is the erythrocyte receptor of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding ligand EBL-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5348–5352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orlandi P. A., Klotz F. W., Haynes J. D. (1992) A malaria invasion receptor, the 175-kilodalton erythrocyte-binding antigen of Plasmodium falciparum, recognizes the terminal Neu5Ac(α2–3)Gal sequences of glycophorin A. J. Cell Biol. 116, 901–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lobo C. A., Rodriguez M., Reid M., Lustigman S. (2003) Glycophorin C is the receptor for the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding ligand PfEBP-2 (baebl). Blood 101, 4628–4631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gilberger T. W., Thompson J. K., Triglia T., Good R. T., Duraisingh M. T., Cowman A. F. (2003) A novel erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 paralogue from Plasmodium falciparum defines a new trypsin-resistant receptor on human erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14480–14486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adams J. H., Sim B. K., Dolan S. A., Fang X., Kaslow D. C., Miller L. H. (1992) A family of erythrocyte-binding proteins of malaria parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7085–7089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kraemer S. M., Smith J. D. (2006) A family affair: var genes, PfEMP1 binding, and malaria disease. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 374–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maier A. G., Duraisingh M. T., Reeder J. C., Patel S. S., Kazura J. W., Zimmerman P. A., Cowman A. F. (2003) Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion through glycophorin C and selection for Gerbich negativity in human populations. Nat. Med. 9, 87–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Long F., Vagin A. A., Young P., Murshudov G. N. (2008) BALBES: a molecular replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hura G. L., Menon A. L., Hammel M., Rambo R. P., Poole F. L., 2nd, Tsutakawa S. E., Jenney F. E., Jr., Classen S., Frankel K. A., Hopkins R. C., Yang S. J., Scott J. W., Dillard B. D., Adams M. W., Tainer J. A. (2009) Robust, high-throughput solution structural analyses by small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS). Nat. Methods 6, 606–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Sokolova A. V., Koch M. H., Svergun D. I. (2003) PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Svergun D., Barberato C., Koch M. H. (1995) CRYSOL–a program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Cryst. 28, 768–773 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franke D., Svergun D. I. (2009) DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 342–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kozin M. B., Svergun D. I. (2001) Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. J. Appl. Cryst. 34, 33–41 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tolia N. H., Enemark E. J., Sim B. K., Joshua-Tor L. (2005) Structural basis for the EBA-175 erythrocyte invasion pathway of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell 122, 183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Batchelor J. D., Zahm J. A., Tolia N. H. (2011) Dimerization of Plasmodium vivax DBP is induced upon receptor binding and drives recognition of DARC. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 908–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh S. K., Hora R., Belrhali H., Chitnis C. E., Sharma A. (2006) Structural basis for Duffy recognition by the malaria parasite Duffy-binding-like domain. Nature 439, 741–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lobo C. A., de Frazao K., Rodriguez M., Reid M., Zalis M., Lustigman S. (2004) Invasion profiles of Brazilian field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum: phenotypic and genotypic analyses. Infect. Immun. 72, 5886–5891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lopaticki S., Maier A. G., Thompson J., Wilson D. W., Tham W. H., Triglia T., Gout A., Speed T. P., Beeson J. G., Healer J., Cowman A. F. (2011) Reticulocyte and erythrocyte binding-like proteins function cooperatively in invasion of human erythrocytes by malaria parasites. Infect. Immun. 79, 1107–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ford L., Lobo C. A., Rodriguez M., Zalis M. G., Machado R. L., Rossit A. R., Cavasini C. E., Couto A. A., Enyong P. A., Lustigman S. (2007) Differential antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum invasion ligand proteins in individuals living in malaria-endemic areas in Brazil and Cameroon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77, 977–983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mayer D. C., Jiang L., Achur R. N., Kakizaki I., Gowda D. C., Miller L. H. (2006) The glycophorin C N-linked glycan is a critical component of the ligand for the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte receptor BAEBL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2358–2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]