Background: Adiponectin modulates inflammatory diseases and dysmetabolism, conditions associated with immune cell activation.

Results: Adiponectin elicits a pro-inflammatory response in human macrophages and promotes TH1 differentiation of isolated CD4+ T cells.

Conclusion: The limited program of inflammatory activation induced by adiponectin likely desensitizes cells to further pro-inflammatory stimuli.

Significance: Interplay of signals regulated by adiponectin may determine its net effect as an inflammatory modulator.

Keywords: Adiponectin, Inflammation, Innate Immunity, Macrophages, T Cell

Abstract

Abundant experimental and clinical data support a modulatory role for adiponectin in inflammation, dysmetabolism, and disease. Because the activation of cells involved in innate and adaptive immunity contributes to the pathogenesis of diseases such as atherosclerosis and obesity, this study investigated the role of adiponectin in human macrophage polarization and T cell differentiation. Examination of the adiponectin-induced transcriptome in primary human macrophages revealed that adiponectin promotes neither classical (M1) nor alternative (M2) macrophage activation but elicits a pro-inflammatory response that resembles M1 more closely than M2. Addition of adiponectin to polyclonally activated CD4+ T lymphocytes did not affect cell proliferation but induced mRNA expression and protein secretion of interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-6. Adiponectin treatment of CD4+ T cells increased phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and signal transducer and activation of transcription (STAT) 4 and augmented T-bet expression. Inhibition of p38 with SB203580 abrogated adiponectin-induced IFN-γ production, indicating that adiponectin enhances TH1 differentiation through the activation of the p38-STAT4-T-bet axis. Collectively, our results demonstrate that adiponectin can induce pro-inflammatory functions in isolated macrophages and T cells, concurring with previous observations that adiponectin induces a limited program of inflammatory activation that likely desensitizes these cells to further pro-inflammatory stimuli.

Introduction

Adipokines, proteins secreted by adipose tissue, regulate local inflammation and influence systemic energy homeostasis and insulin sensitivity at a distance. Adiponectin, the most abundant adipokine, circulates in human plasma at levels of 3–30 μg/ml, accounting for 0.01% of total plasma protein. Adiponectin exists in the circulation in three major oligomeric complexes, trimer, hexamer, and higher molecular weight multimers (collectively referred to as full-length adiponectin) and in a less abundant bioactive proteolytic product that contains the protein's C1q-like globular domain (1–4).

Adiponectin has gained recognition as a key vasculoprotective protein with insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory properties (2–5). Numerous clinical studies have correlated hypoadiponectinemia with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, as well as with dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (6–13). Other studies, however, report no association of plasma adiponectin levels with coronary artery disease (14–16). Experimental studies have demonstrated that adiponectin deficiency leads to the development of larger atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic root of adiponectin (APN)−/− apolipoprotein E (ApoE)−/− doubly deficient mice compared with ApoE−/− controls (17) and to augmented thrombus formation after carotid arterial injury in mice (18), but a recent study that used APN−/− mice or transgenic mice with chronically elevated adiponectin levels crossed with ApoE−/− or low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)−/− mice found no correlation between adiponectin and atheroma development (19). Thus, the net effect of adiponectin in this chronic inflammatory condition remains controversial.

Adiponectin exerts anti-inflammatory actions in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages, which are the major cell types found in atheroma (2–4). In macrophages, adiponectin reduces cholesteryl ester accumulation by suppressing the expression of class A scavenger receptors (20) and may favor plaque stabilization by inducing tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 production (21). We (17) and others (22–25) have demonstrated that treatment with adiponectin inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages from different sources. In human macrophages, adiponectin inhibits multiple pro-inflammatory signaling pathways elicited by LPS, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and interleukin (IL)-6 (26).

Macrophages, key participants in innate immunity, exhibit diversity and plasticity; they can exhibit “classical activation” (M1), associated with pro-inflammatory responses directed to eliminate intracellular pathogens, or “alternative activation” (M2), oriented to tissue remodeling and regulation of immune responses (27). Distinct expression profiles of a host of genes that encode membrane receptors, solute carriers, enzymes, cytokines, and chemokines characterize the M1 and M2 phenotypes (28). These expression profiles show considerable variation between species. Recent studies that examined the effect of adiponectin on the expression of a limited number of macrophage polarization markers concluded that this adipokine promotes the M2 phenotype in rodent and human macrophages (29–31). But we currently lack a more comprehensive analysis of the adiponectin-induced transcriptome associated with human macrophage polarization.

T cells modulate the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and allograft arteriopathy (32). In atheromata, CD4+ T cells respond to local cytokines and to antigenic stimulation by undergoing distinct programs of activation that lead to different T-helper (TH) subsets, which differentially influence plaque evolution. TH1 cells generally predominate in atheroma, where they secrete interferon-γ (IFN-γ), a cytokine that inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation and collagen production and activates macrophages. TH2 cells secrete IL-4 and IL-13, cytokines that induce alternative activation of macrophages and may mitigate inflammation (32–34). Studies using mixed cell populations to investigate the effect of adiponectin on the inflammatory properties of T cells have yielded disparate results. Adiponectin limits T cell accumulation in cultures of mouse splenocytes (35) and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)3 (36) upon polyclonal stimulation and inhibits (36) or stimulates (37) T cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines after antigen-specific stimulation of PBMCs. The direct effect of adiponectin on purified T lymphocytes remains unresolved.

We and others have demonstrated that short-term treatment of macrophages with adiponectin initially induces pro-inflammatory signaling (26, 38), consistent with a bimodal macrophage response to adiponectin and suggesting that early pro-inflammatory events may ultimately mute the response to classical pro-inflammatory stimuli. This study tested the hypothesis that adiponectin can actually promote, rather than limit, inflammatory responses both in isolated human macrophages and in CD4+ T lymphocytes, cells that participate critically in the innate and adaptive immune responses that operate in atheroma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Human recombinant full-length adiponectin expressed in HEK293 cells was purchased from BioVendor (Candler, NC). It contained less than 40 pg of endotoxin/μg, as determined by the chromogenic Limulus amebocyte assay (Cape Cod, Falmouth, MA). Antibodies to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr-180/Tyr-182), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2, phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204), 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), phospho-AMPK (Thr-172), β-actin, signal transducer and activation of transcription (STAT) 1 and 4, phospho-STAT1 (Tyr-701), and phospho-STAT4 (Tyr-693) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); anti-T-bet antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human IFN-γ, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human CD4, and their corresponding isotype control antibodies were from Biolegend (San Diego). Anti-IFN-γ-neutralizing and IgG isotype control antibodies were from eBioscience; anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and recombinant human IL-2 were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). U0126 was from Cell Signaling; compound C was from Calbiochem, and SB203580 and polymyxin B were from Sigma.

Isolation and Treatment of Human Macrophages and CD4+ T Cells

Human monocytes were isolated from freshly prepared PBMCs and differentiated to macrophages for 10 days in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% human serum, as described previously (26). To test the effects of adiponectin on gene expression, macrophages were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% human serum with or without adiponectin (5 or 10 μg/ml as indicated) for various time intervals.

CD4+ T cells were sorted magnetically from PBMCs using a human CD4+ T cell isolation kit II from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. A purity of >90% was confirmed by flow cytometry. To test the effect of adiponectin on T cell differentiation, CD4+ T cells (2.5 × 106/ml) were incubated for the indicated time intervals in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb, soluble anti-CD28 mAb (1 μg/ml), and recombinant human IL-2 (100 units/ml), with or without different concentrations of adiponectin.

To test the function of CD4+ T cell supernatants, CD4+ T cells were cultured with or without adiponectin (5 μg/ml) for 4 days, washed, and then re-stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAb for 2 days. Different dilutions (1:10 or 1:100) of T cell-conditioned media were added to macrophages and incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% human serum, in the presence of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ or IgG isotype control antibodies (10 μg/ml) for 24 h.

Microarray Analysis

Macrophages from four independent donors were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% human serum, with or without 10 μg/ml adiponectin, for 24 h. Ten micrograms of total RNA were tested for quality on agarose gels and subjected to microarray screening on Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0 chips. Criteria for differential regulation were set as >2-fold increase or decrease at a probability value of <0.05.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription-Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse-transcribed by Superscript II (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed in a MyiQ Single-Color Real Time PCR system using SYBR Green I (Bio-Rad). The mRNA levels of the various genes tested were normalized to 18 S as an internal control for adjustment between samples. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of RT-PCR primers

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| AdipoR1 | 5′-TCTTTTTGGGTGCAGTGCT-3′ | 5′-GCAATTCCTGAATAGTCCAGTT-3′ |

| AdipoR2 | 5′-GGGCATTGCAGCCATTAT-3′ | 5′-TAGGCCCAAAAACACTCCTG-3′ |

| IFN-γ | 5′-TCTGGAGGAACTGGCAAAAG-3′ | 5′-TTCAAGACTTCAAAGAGTCTGAGG-3′ |

| MHC-II | 5′-TCTTCATCATCAAGGGATTGC-3′ | 5′-TTCTCTCTAAGAAACACCATCACCT-3′ |

| IL-4 | 5′-CACCGAGTTGACCGTAACAG-3′ | 5′-GCCCTGCAGAAGGTTTCC-3′ |

| IL-6 | 5′-AGTGAGGAACAAGCCAGAGCTGTCC-3′ | 5′-AATCTGAGGTGCCCATGCTACATTTG-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-ATCTACTCCCAGGTCCTCTTCAA-3′ | 5′-GCAATGATCCCAAAGTAGACCT-3′ |

| IP-10 | 5′-GCTGCCGTCATTTTCTGC-3′ | 5′-TCTCACTGGCCCGTCATC-3′ |

| CCL18 | 5′-ACCTTCAACATGAAAGTCTCTGC-3′ | 5′-GGACGTTGAGTGCATCTGG-3′ |

| CCL23 | 5′-CACCAGGAGGATGAAGGTCT-3′ | 5′-TCATGAACTCTGTCTCTGCATCT-3′ |

| PPAR-γ | 5′-TTGCTGTCATTATTCTCAGTGGA-3′ | 5′-GAGGACTCAGGGTGG TTCAG-3′ |

| MRC1 | 5′-CACCATCGAGGAATTGGACT-3′ | 5′-ACAATTCGTCATTTGGCTCA-3′ |

| CD163 | 5′-GAAGATGCTGGCGTGACAT-3′ | 5′-GCTGCCTCCACCTCTAAGTC-3′ |

| 18 S | 5′-ATGGCCGTTCTTAGTTGGTG-3′ | 5′-GAACGCCACTTGTCCCTCTA-3′ |

Western Blot

Whole cell lysates from 100,000 cells were fractionated on 4–12% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% defatted milk and incubating with the appropriate antibodies, membranes were developed using a chemiluminescence reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Cytokine Assays

The concentrations of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-4 in culture supernatants were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems). All assays were performed in triplicate.

RNA Interference

Macrophages were transfected with a pool of AdipoR-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes (Dharmacon) at 50 nm using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. A pool of nontargeting siRNA duplexes was used as a control. Experiments were conducted 48 h after transfection.

Flow Cytometry

For surface staining, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD4 for 20 min at 4 °C. To determine TH1 cell frequencies, cells were re-stimulated with leukocyte activation mixture (GolgiPlug from Pharmingen) for 6 h, then fixed, and permeabilized before adding allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human IFN-γ antibody. Isotype controls were used to confirm antibody specificity. The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± S.E. Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance, followed by a post hoc SNK test, was used for comparisons among two or more groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Adiponectin Exerts Pro-Inflammatory Effects on Human Macrophages

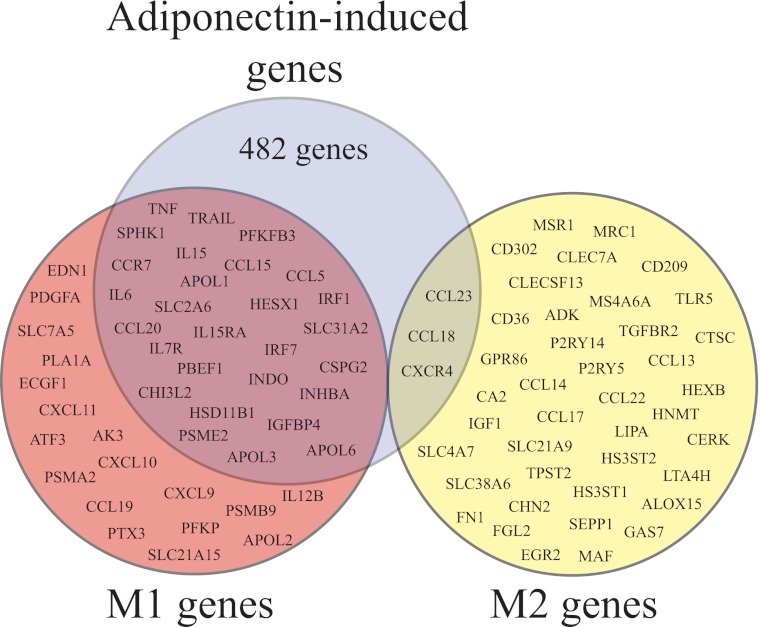

A comprehensive analysis of the transcriptional profiles exhibited by classically (M1) and alternatively (M2) activated human macrophages has shown differential expression of a vast number of genes in these two conditions (28). To investigate the effect of adiponectin on human macrophage polarization, we examined the expression level of a selected group of 89 genes strictly associated with the M1 or M2 phenotype (28). Transcriptional profiling of macrophages exposed to 10 μg/ml adiponectin for 24 h compared with control cells showed that adiponectin induced the expression of 28 of the 46 M1 markers (including the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6) and only 3 of the 43 M2 markers, while reducing the expression of 14 M2 markers (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table 1). Adiponectin also induced the expression of 451 genes unrelated to the M1 or M2 phenotypes (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of adiponectin on the expression of genes associated with human macrophage polarization. Macrophages were stimulated with 10 μg/ml adiponectin for 24 h, and mRNA underwent microarray analysis as described under “Materials and Methods.” The diagram illustrates that adiponectin induces the expression of 482 genes (blue), 28 of which associate with classical (M1) macrophage activation (red), and 3 of which associate with alternative (M2) macrophage activation (yellow). The supplemental Table 1 shows a description of the magnitude of the changes in the expression of these polarization markers.

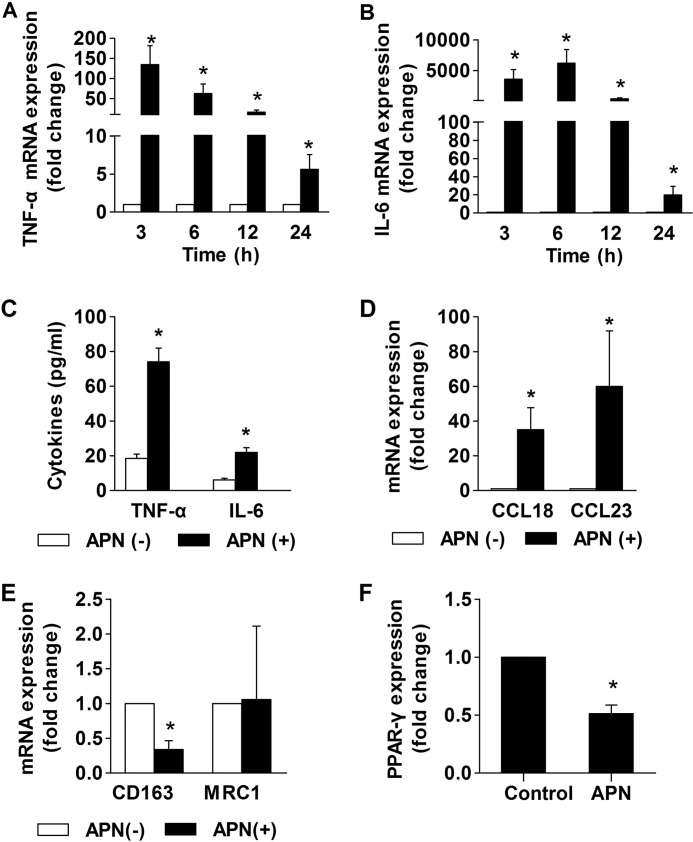

To validate the cDNA microarray data, RT-qPCR tested the time-dependent induction of the M1 markers TNF-α and IL-6 in macrophages stimulated by adiponectin. The mRNAs that encode these cytokines reached maximal levels of expression at 3–6 h after the addition of adiponectin and then declined (Fig. 2, A and B). Concordant with the observed increase in mRNA expression, adiponectin treatment induced the release of TNF-α and IL-6 proteins from macrophages (Fig. 2C). A 15-min preincubation at 100 °C abrogated adiponectin-induced TNF-α and IL-6 expression (supplemental Fig. 1). Pretreatment of macrophages with 1 μg/ml polymyxin B (26) did not inhibit the expression of these cytokines, corroborating that their induction did not stem from endotoxin contamination (data not shown). RT-qPCR also validated the induction of the M2 genes CCL18 and CCL23 (Fig. 2D) and the lack of induction of the M2 marker mannose receptor C type 1 (MRC1) (Fig. 2E) in macrophages stimulated by adiponectin for 24 h. Treatment with adiponectin reduced the expression of CD163, an M2 marker not represented in the microarrays used in our transcriptional profiling (Fig. 2E), and of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), a transcription factor that participates in alternative activation of mouse macrophages (Fig. 2F) (39). Adiponectin did not induce IFN-γ expression in macrophages (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that adiponectin promotes neither classical nor alternative activation of human macrophages but induces a pro-inflammatory phenotype that resembles M1 more closely than M2.

FIGURE 2.

Adiponectin induces expression of M1 and M2 cytokines in human macrophages. Macrophages were stimulated with 10 μg/ml adiponectin for the indicated times (A and B) or for 24 h (C–F). RT-qPCR measured the levels of the indicated mRNAs, using 18 S as an internal control (A, B, and D–F). ELISA determined the concentration of the indicated cytokines in cell supernatants (C). Data are expressed as means ± S.E. (n = 3–4) relative to the values of samples from vehicle-treated cells at the respective time points. *, p < 0.05 versus APN(−).

Human macrophages express both adiponectin receptors, AdipoR1 and AdipoR2. Transfection of AdipoR-specific siRNA reduced the expression of the respective AdipoR mRNA by 70–80% (supplemental Fig. 2A). siRNA-mediated knockdown of AdipoR1, AdipoR2, or the combination of both mitigated adiponectin-induced TNF-α (supplemental Fig. 2B) and IL-6 (supplemental Fig. 2C) expression, indicating that both receptors participate in the action of adiponectin.

Adiponectin Promotes TH1 Differentiation of Isolated CD4+ T Cells

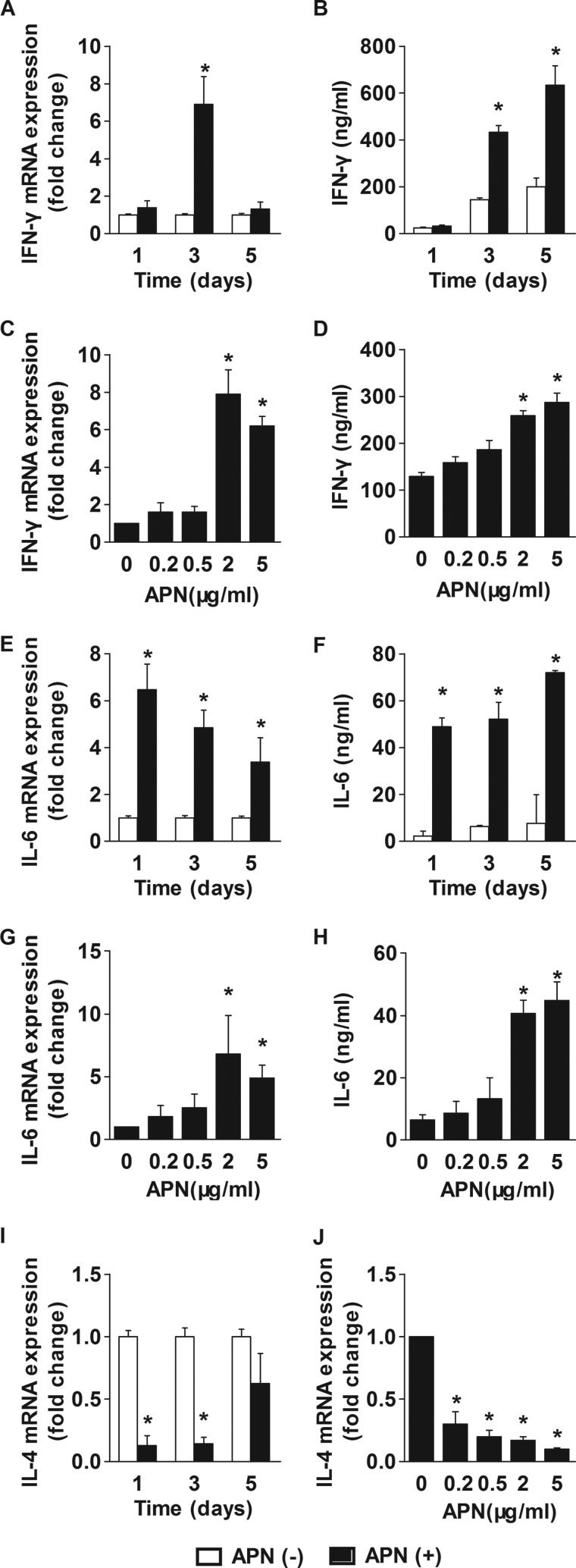

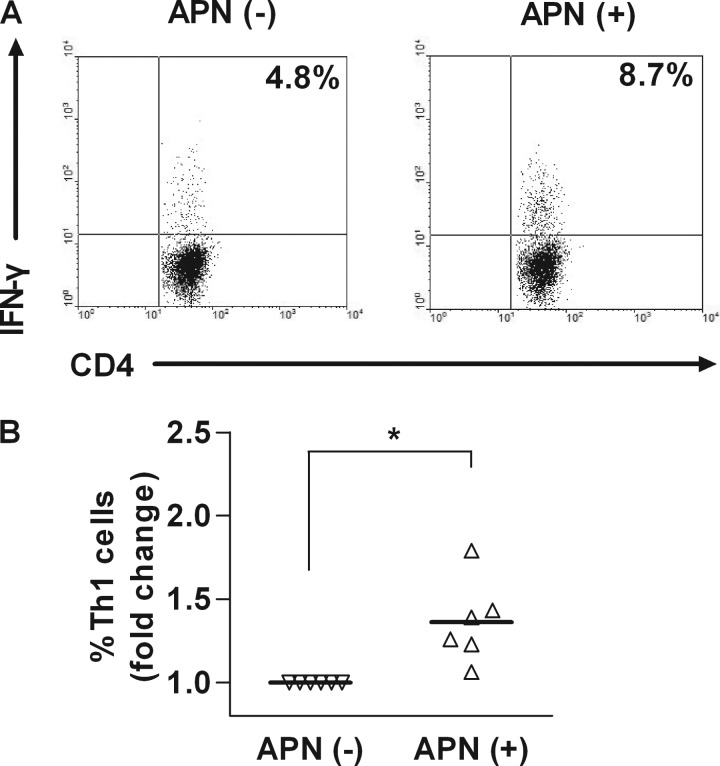

Abundant data implicate CD4+ T lymphocytes in atheroma development (32). Examination of the expression of the adiponectin receptors, AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, in these cells concurred with a previous report (37) showing that CD4+ T cells express AdipoR1 preferentially (data not shown). To investigate the effects of adiponectin on purified CD4+ T cells, we subjected these human cells to polyclonal stimulation in the presence or absence of adiponectin and examined the expression of IFN-γ and IL-4, signature cytokines of the TH1 and TH2 lineages, respectively, and of the broad inflammatory mediator IL-6. Exposure of CD4+ T cells to adiponectin increased IFN-γ mRNA expression and protein secretion (Fig. 3) without affecting T cell proliferation (data not shown). The level of IFN-γ mRNA peaked 3 days after starting stimulation with adiponectin and then decreased (Fig. 3A), whereas IFN-γ protein accumulated in the media over the course of the experiment (Fig. 3B). Adiponectin did not induce changes in the expression levels of IL-2, a cytokine important for T cell proliferation (data not shown). Treatment of CD4+ T cells with adiponectin increased the frequencies of cells containing IFN-γ, as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4). Adiponectin induced IFN-γ expression at concentrations of 2 μg/ml or higher (Fig. 3, C and D). Pretreatment with polymyxin (1 μg/ml) did not affect IFN-γ secretion, indicating that adiponectin's actions did not result from endotoxin contamination (supplemental Fig. 3). Adiponectin also induced sustained IL-6 expression. IL-6 mRNA and protein levels reached maximal values 1 day after the addition of adiponectin and remained high over the course of the experiment (Fig. 3, E and F). IL-6 induction depended on adiponectin concentration similarly to IFN-γ induction (Fig. 3, G and H). Adiponectin inhibited the basal expression of IL-4 mRNA in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3, I and J). The level of IL-4 protein in T cell-conditioned media fell below the detection limit of the ELISA kits used. The presence of adiponectin during CD4+ T cell differentiation did not alter the expression levels of FoxP3, a marker of regulatory T cells. Collectively, these results indicate that adiponectin promotes CD4+ T cell differentiation toward a TH1 lineage.

FIGURE 3.

Adiponectin regulates cytokine expression in human CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence or absence of 5 μg/ml adiponectin for the indicated periods of time (A, B, E, F, and I) or with various adiponectin concentrations for 3 days (C, D, G, H, and J). RT-qPCR measured the levels of the indicated mRNAs, using 18 S as an internal control (A, C, E, G, I, and J). ELISA determined the concentration of the indicated cytokines in cell supernatants (B, D, F, and H). Data are expressed as means ± S.E. (n = 3) relative to the values of samples from vehicle-treated cells at the respective time points. *, p < 0.05 versus APN(−).

FIGURE 4.

Adiponectin promotes TH1 differentiation of human CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 in the absence or presence of 5 μg/ml adiponectin for 3 days. Flow cytometry determined the frequency of CD4+IFN-γ+ cells. A, representative FACS plots from one donor. B, collective analysis of results from six different donors. *, p < 0.05 versus APN (−).

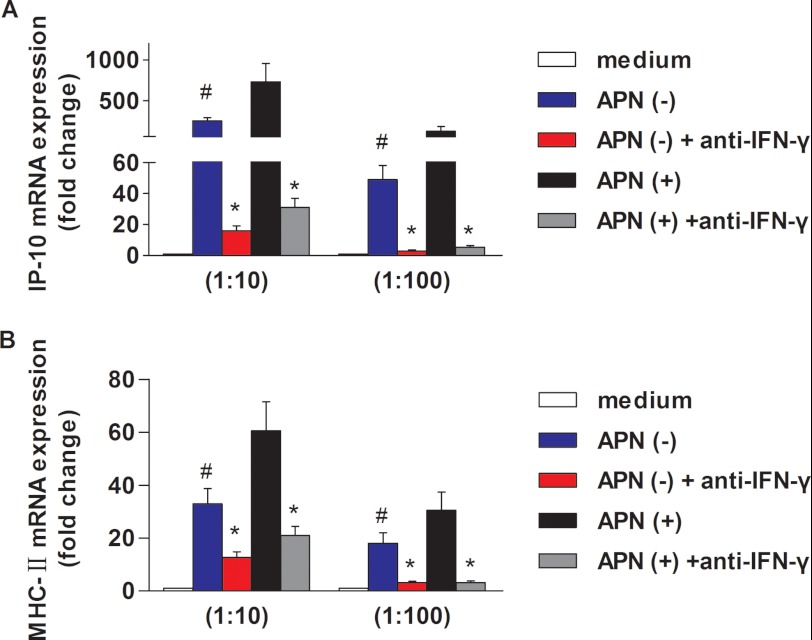

We validated the adiponectin-induced IFN-γ secretion from T cells at a functional level by treating primary human macrophages with conditioned media from adiponectin-treated or control T cells. Supernatants of CD4+ T cells incubated with adiponectin stimulated the macrophage expression of CXCL10 (10-kDa interferon-γ-induced protein, IP-10) (Fig. 5A) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC), class II, DRα (HLA-DRA) (Fig. 5B), two well established IFN-γ-inducible genes, to a greater extent than did supernatants from control CD4+ T cells. Blocking antibodies against IFN-γ limited both basal and adiponectin-enhanced CXCL10/IP-10 and MHC class II antigen induction.

FIGURE 5.

Conditioned media from adiponectin-treated CD4+ T cells increases CXCL10/IP-10 and HLA-DRA expression in human macrophages. Macrophages were incubated for 24 h with different dilutions (1:10 or 1:100) of conditioned media from CD4+ T cells that had been treated with or without 5 μg/ml adiponectin (as described under “Materials and Methods”), in the presence of anti-IFN-γ-neutralizing antibody or IgG isotype control. RT-qPCR measured the levels of IP-10 (A) and MHC-II (B) mRNA, using 18 S as an internal control. *, p < 0.05 versus IgG isotype control; #, p < 0.05 versus APN (+).

Adiponectin Induces Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and STAT4 and Enhances T-bet Expression in Human CD4+ T Cells

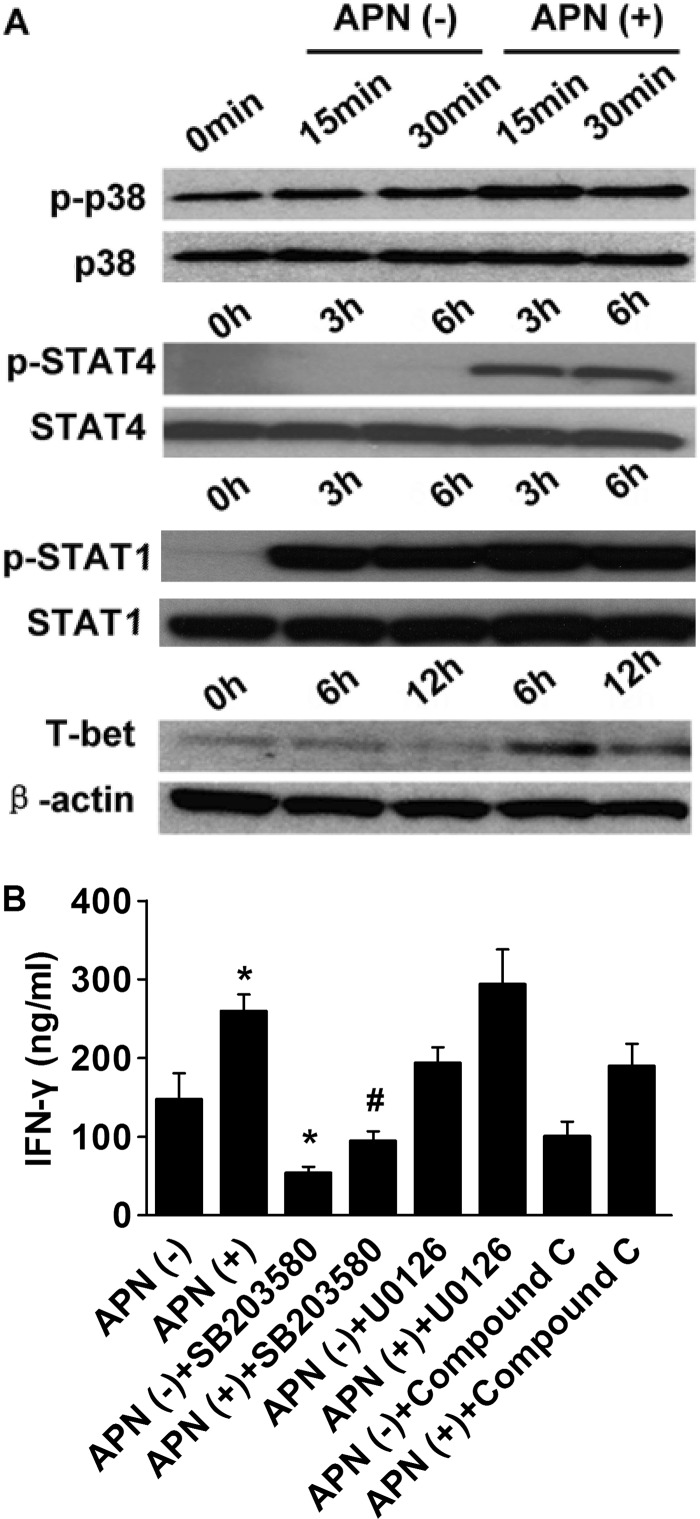

AMPK, p38 MAPK, and ERK1/2 mediate many of the cellular effects of adiponectin (40, 41). Treatment of CD4+ T cells with adiponectin induced rapid p38 phosphorylation above its basal level (Fig. 6A), but it did not affect ERK1/2 and AMPK phosphorylation (data not shown). Preincubation of CD4+ T cells with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 reduced both basal and adiponectin-stimulated IFN-γ secretion, whereas addition of U0126 (a MAPK kinase (MEK) 1 and 2 inhibitor) or compound C (an AMPK inhibitor) did not influence T cell differentiation (Fig. 6B). These results implicate p38 as a critical adiponectin-regulated mediator of T cell differentiation.

FIGURE 6.

Adiponectin induces p38 MAPK and STAT4 phosphorylation and enhances T-bet expression in human CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were incubated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAbs in the presence or absence of 5 μg/ml adiponectin for the indicated periods of time. A, whole cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to phospho-p38, phospho-STAT4, phospho-STAT1, or T-bet. Total p38, STAT4, STAT1, and β-actin served as loading controls, respectively. Images are representative of three independent experiments that used cells from different donors. B, cells were incubated as in A for 72 h, with the addition of SB203850 (10 μm), U0126 (10 μm), or compound C (10 μm), as indicated. The inhibitors were added 30 min before adiponectin. ELISA measured the IFN-γ concentration in cell supernatants. *, p < 0.05 versus APN (−); #, p < 0.05 versus APN (+).

The signaling molecules STAT1 and STAT4 and the lineage-specific transcription factor T-bet mediate the development of the TH1 response (42). Treatment of CD4+ T cells with adiponectin markedly induced phosphorylation of STAT4, but not of STAT1, and enhanced T-bet expression (Fig. 6A). Collectively, our results indicate that adiponectin enhances TH1 differentiation through the activation of the p38 MAPK-STAT4-T-bet axis.

DISCUSSION

Obesity and atherosclerosis, traditionally viewed as bland lipid-storage diseases, rather involve ongoing inflammation characterized by activation of both innate and adaptive immunity. The correlation of hypoadiponectinemia with obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis in humans (6–13), as well as with systemic inflammation and elevated plasma levels of C-reactive protein (43), have led to the hypothesis that adiponectin moderates inflammation and immunity (44). This study aimed to contribute to understanding of the functions of adiponectin in human cells critically involved in these processes by examining its role in macrophage polarization and T cell differentiation.

Macrophages respond to diverse stimuli by undergoing either classical (M1) or alternative (M2) activation programs. In view of the numerous anti-inflammatory effects attributed to adiponectin, several recent studies tested the effect of adiponectin on macrophage polarization, suggesting that this adipokine promotes alternative activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages, RAW264.7 cells, and rat Kupffer cells (29, 31). The expression profiles associated with macrophage polarization exhibit important interspecies differences, with only 50% of polarization markers coinciding in humans and mice (28). Two recent studies examined the effect of adiponectin on markers of human macrophage polarization and concluded that adiponectin induces M2 polarization in these cells. Ohashi et al. (29) showed that treatment of macrophages with adiponectin for 48 h increases the expression of the mannose receptor (MRC), and Lovren et al. (30) reported that when adiponectin is added during monocyte differentiation it primes macrophages for augmented expression of MRC and CCL18 upon IL4 stimulation. Limitations of these studies include the complexity of macrophage polarization, a process associated with changes in the expression of numerous genes, not only MRC and CCL18 (28). In contrast to these previous studies, our analysis of the adiponectin-induced transcriptome showed that adiponectin promotes neither classical nor alternative activation of human macrophages. Instead, it favors a pro-inflammatory functional palette, with augmented expression of 28 of 46 genes strictly associated with M1 and only 3 of 43 genes characteristic of M2 (28), and it reduces the expression of 14 M2 markers. Mandal et al. (31) recently reported that full-length adiponectin polarizes RAW264.7 macrophages to an M2 phenotype, in a manner dependent on the autocrine/paracrine action of IL4 induced by adiponectin. We did not detect IL4 induction by adiponectin in human primary macrophages (data not shown), which likely reflects important interspecies variations in the cellular mechanisms that promote macrophage polarization.

Several studies that reported immunomodulatory functions of adiponectin in sepsis and inflammatory diseases in animals (17, 35, 45–47) have stimulated the study of regulation of T cell functions by adiponectin. We demonstrated that addition of adiponectin to mouse splenocytes stimulated with a polyclonal activator of T cells inhibits T cell proliferation and production of IFN-γ and TNF-α, without affecting apoptosis (35). In contrast, adiponectin limits both T cell proliferation and apoptosis when added to human PBMCs together with a polyclonal T cell activator (36). Recent studies addressing the role of adiponectin on the expansion of antigen-specific T cell populations from human PBMCs have also yielded discordant results as follows: adiponectin reduced the number of influenza-specific T cells producing IFN-γ and TNF-α (36) but increased IFN-γ production by hepatitis C virus-specific T cells (37). These results indicate that the action of adiponectin on T cell differentiation and function varies among species and that the experimental conditions used in vitro (e.g. cellular composition, cytokine profile, and presence of antigens) can influence adiponectin's action decisively. This study therefore aimed to shed light on the direct effect of adiponectin on T cells in the absence of environmental cues originating in other cell types. Our results show that the addition of adiponectin to purified CD4+ T cells enhances TH1 differentiation through the activation of p38 MAPK and STAT4, two crucial signaling proteins in the TH1 response (48, 49), and by the induction of T-bet, the master transcription factor for TH1 differentiation (50).

In light of the numerous anti-inflammatory functions attributed to adiponectin, our findings that adiponectin promotes inflammation in isolated macrophages and T cells may seem paradoxical. But these data concur with previous observations by our group (26) and by others (38, 51) that adiponectin induces a degree of inflammatory activation in macrophages that likely mediates tolerance to further pro-inflammatory stimuli. The mechanism that leads to subsequent macrophage hyporesponsiveness remains unclear, but our previous work has suggested that adiponectin induces sustained expression of various anti-inflammatory molecules in these cells, including A20, BCL3, SOCS3, and TRAF1, which likely mute further activation (26). These observations suggest that the results of short-term in vitro experiments involving acute exposure of cells to a mediator may not reflect the biology of cells that encounter tonically elevated levels of the mediator. The net effect of adiponectin as a modulator of inflammation in local environments in vivo, such as the atheroma, therefore likely depends on a complex interplay of adiponectin-regulated signals in different cells integrated over time. Dissection of these pathways in isolated cells therefore will help to unravel the roles of adiponectin in such lesions.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–3 and Table 1.

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- AMPK

- 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase

- MRC1

- mannose receptor C, type 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arita Y., Kihara S., Ouchi N., Takahashi M., Maeda K., Miyagawa J., Hotta K., Shimomura I., Nakamura T., Miyaoka K., Kuriyama H., Nishida M., Yamashita S., Okubo K., Matsubara K., Muraguchi M., Ohmoto Y., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y. (1999) Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 257, 79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldstein B. J., Scalia R. G., Ma X. L. (2009) Protective vascular and myocardial effects of adiponectin. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okamoto Y., Kihara S., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y., Libby P. (2006) Adiponectin. A key adipocytokine in metabolic syndrome. Clin. Sci. 110, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu W., Cheng K. K., Vanhoutte P. M., Lam K. S., Xu A. (2008) Vascular effects of adiponectin. Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic intervention. Clin. Sci. 114, 361–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trujillo M. E., Scherer P. E. (2005) Adiponectin. Journey from an adipocyte secretory protein to biomarker of the metabolic syndrome. J. Intern. Med. 257, 167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hotta K., Funahashi T., Arita Y., Takahashi M., Matsuda M., Okamoto Y., Iwahashi H., Kuriyama H., Ouchi N., Maeda K., Nishida M., Kihara S., Sakai N., Nakajima T., Hasegawa K., Muraguchi M., Ohmoto Y., Nakamura T., Yamashita S., Hanafusa T., Matsuzawa Y. (2000) Plasma concentrations of a novel adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 1595–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumada M., Kihara S., Sumitsuji S., Kawamoto T., Matsumoto S., Ouchi N., Arita Y., Okamoto Y., Shimomura I., Hiraoka H., Nakamura T., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y., and Osaka CAD Study Group (2003) Association of hypoadiponectinemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ouchi N., Ohishi M., Kihara S., Funahashi T., Nakamura T., Nagaretani H., Kumada M., Ohashi K., Okamoto Y., Nishizawa H., Kishida K., Maeda N., Nagasawa A., Kobayashi H., Hiraoka H., Komai N., Kaibe M., Rakugi H., Ogihara T., Matsuzawa Y. (2003) Association of hypoadiponectinemia with impaired vasoreactivity. Hypertension 42, 231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li S., Shin H. J., Ding E. L., van Dam R. M. (2009) Adiponectin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 302, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iwashima Y., Katsuya T., Ishikawa K., Ouchi N., Ohishi M., Sugimoto K., Fu Y., Motone M., Yamamoto K., Matsuo A., Ohashi K., Kihara S., Funahashi T., Rakugi H., Matsuzawa Y., Ogihara T. (2004) Hypoadiponectinemia is an independent risk factor for hypertension. Hypertension 43, 1318–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsubara M., Maruoka S., Katayose S. (2002) Decreased plasma adiponectin concentrations in women with dyslipidemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 2764–2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kazumi T., Kawaguchi A., Hirano T., Yoshino G. (2004) Serum adiponectin is associated with high density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and low density lipoprotein particle size in young healthy men. Metabolism 53, 589–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schulze M. B., Rimm E. B., Shai I., Rifai N., Hu F. B. (2004) Relationship between adiponectin and glycemic control, blood lipids, and inflammatory markers in men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27, 1680–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sattar N., Wannamethee G., Sarwar N., Tchernova J., Cherry L., Wallace A. M., Danesh J., Whincup P. H. (2006) Adiponectin and coronary heart disease. A prospective study and meta-analysis. Circulation 114, 623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lindsay R. S., Resnick H. E., Zhu J., Tun M. L., Howard B. V., Zhang Y., Yeh J., Best L. G. (2005) Adiponectin and coronary heart disease. The Strong Heart Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, e15–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lawlor D. A., Davey Smith G., Ebrahim S., Thompson C., Sattar N. (2005) Plasma adiponectin levels are associated with insulin resistance but do not predict future risk of coronary heart disease in women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 5677–5683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okamoto Y., Folco E. J., Minami M., Wara A. K., Feinberg M. W., Sukhova G. K., Colvin R. A., Kihara S., Funahashi T., Luster A. D., Libby P. (2008) Adiponectin inhibits the production of CXC receptor 3 chemokine ligands in macrophages and reduces T-lymphocyte recruitment in atherogenesis. Circ. Res. 102, 218–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kato H., Kashiwagi H., Shiraga M., Tadokoro S., Kamae T., Ujiie H., Honda S., Miyata S., Ijiri Y., Yamamoto J., Maeda N., Funahashi T., Kurata Y., Shimomura I., Tomiyama Y., Kanakura Y. (2006) Adiponectin acts as an endogenous antithrombotic factor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 224–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nawrocki A. R., Hofmann S. M., Teupser D., Basford J. E., Durand J. L., Jelicks L. A., Woo C. W., Kuriakose G., Factor S. M., Tanowitz H. B., Hui D. Y., Tabas I., Scherer P. E. (2010) Lack of association between adiponectin levels and atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1159–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ouchi N., Kihara S., Arita Y., Nishida M., Matsuyama A., Okamoto Y., Ishigami M., Kuriyama H., Kishida K., Nishizawa H., Hotta K., Muraguchi M., Ohmoto Y., Yamashita S., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y. (2001) Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation 103, 1057–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kumada M., Kihara S., Ouchi N., Kobayashi H., Okamoto Y., Ohashi K., Maeda K., Nagaretani H., Kishida K., Maeda N., Nagasawa A., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y. (2004) Adiponectin specifically increased tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 through interleukin-10 expression in human macrophages. Circulation 109, 2046–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wulster-Radcliffe M. C., Ajuwon K. M., Wang J., Christian J. A., Spurlock M. E. (2004) Adiponectin differentially regulates cytokines in porcine macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 924–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thakur V., Pritchard M. T., McMullen M. R., Nagy L. E. (2006) Adiponectin normalizes LPS-stimulated TNF-α production by rat Kupffer cells after chronic ethanol feeding. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 290, G998–G1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamaguchi N., Argueta J. G., Masuhiro Y., Kagishita M., Nonaka K., Saito T., Hanazawa S., Yamashita Y. (2005) Adiponectin inhibits Toll-like receptor family induced signaling. FEBS Lett. 579, 6821–6826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yokota T., Oritani K., Takahashi I., Ishikawa J., Matsuyama A., Ouchi N., Kihara S., Funahashi T., Tenner A. J., Tomiyama Y., Matsuzawa Y. (2000) Adiponectin, a new member of the family of soluble defense collagens, negatively regulates the growth of myelomonocytic progenitors and the functions of macrophages. Blood 96, 1723–1732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Folco E. J., Rocha V. Z., López-Ilasaca M., Libby P. (2009) Adiponectin inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling in human macrophages independent of interleukin-10. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25569–25575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martinez F. O., Helming L., Gordon S. (2009) Alternative activation of macrophages. An immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 451–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinez F. O., Gordon S., Locati M., Mantovani A. (2006) Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization. New molecules and patterns of gene expression. J. Immunol. 177, 7303–7311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohashi K., Parker J. L., Ouchi N., Higuchi A., Vita J. A., Gokce N., Pedersen A. A., Kalthoff C., Tullin S., Sams A., Summer R., Walsh K. (2010) Adiponectin promotes macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6153–6160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lovren F., Pan Y., Quan A., Szmitko P. E., Singh K. K., Shukla P. C., Gupta M., Chan L., Al-Omran M., Teoh H., Verma S. (2010) Adiponectin primes human monocytes into alternative anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ Physiol. 299, H656–H663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mandal P., Pratt B. T., Barnes M., McMullen M. R., Nagy L. E. (2011) Molecular mechanism for adiponectin-dependent M2 macrophage polarization. Link between the metabolic and innate immune activity of full-length adiponectin. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13460–13469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansson G. K., Libby P. (2006) The immune response in atherosclerosis. A double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 508–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weber C., Zernecke A., Libby P. (2008) The multifaceted contributions of leukocyte subsets to atherosclerosis. Lessons from mouse models. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 802–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schulte S., Sukhova G. K., Libby P. (2008) Genetically programmed biases in Th1 and Th2 immune responses modulate atherogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 172, 1500–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okamoto Y., Christen T., Shimizu K., Asano K., Kihara S., Mitchell R. N., Libby P. (2009) Adiponectin inhibits allograft rejection in murine cardiac transplantation. Transplantation 88, 879–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilk S., Scheibenbogen C., Bauer S., Jenke A., Rother M., Guerreiro M., Kudernatsch R., Goerner N., Poller W., Elligsen-Merkel D., Utku N., Magrane J., Volk H. D., Skurk C. (2011) Adiponectin is a negative regulator of antigen-activated T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2323–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palmer C., Hampartzoumian T., Lloyd A., Zekry A. (2008) A novel role for adiponectin in regulating the immune responses in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 48, 374–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Park P. H., McMullen M. R., Huang H., Thakur V., Nagy L. E. (2007) Short-term treatment of RAW264.7 macrophages with adiponectin increases tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression via ERK1/2 activation and Egr-1 expression. Role of TNF-α in adiponectin-stimulated interleukin-10 production. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 21695–21703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Odegaard J. I., Ricardo-Gonzalez R. R., Goforth M. H., Morel C. R., Subramanian V., Mukundan L., Red Eagle A., Vats D., Brombacher F., Ferrante A. W., Chawla A. (2007) Macrophage-specific PPARγ controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature 447, 1116–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yamauchi T., Kamon J., Ito Y., Tsuchida A., Yokomizo T., Kita S., Sugiyama T., Miyagishi M., Hara K., Tsunoda M., Murakami K., Ohteki T., Uchida S., Takekawa S., Waki H., Tsuno N. H., Shibata Y., Terauchi Y., Froguel P., Tobe K., Koyasu S., Taira K., Kitamura T., Shimizu T., Nagai R., Kadowaki T. (2003) Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature 423, 762–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee M. H., Klein R. L., El-Shewy H. M., Luttrell D. K., Luttrell L. M. (2008) The adiponectin receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 activate ERK1/2 through a Src/Ras-dependent pathway and stimulate cell growth. Biochemistry 47, 11682–11692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cui G., Qin X., Zhang Y., Gong Z., Ge B., Zang Y. Q. (2009) Berberine differentially modulates the activities of ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK to suppress Th17 and Th1 T cell differentiation in type 1 diabetic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28420–28429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Otake H., Shite J., Shinke T., Watanabe S., Tanino Y., Ogasawara D., Sawada T., Hirata K., Yokoyama M. (2008) Relation between plasma adiponectin, high sensitivity C-reactive protein, and coronary plaque components in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 101, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berg A. H., Scherer P. E. (2005) Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 96, 939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uji Y., Yamamoto H., Tsuchihashi H., Maeda K., Funahashi T., Shimomura I., Shimizu T., Endo Y., Tani T. (2009) Adiponectin deficiency is associated with severe polymicrobial sepsis, high inflammatory cytokine levels, and high mortality. Surgery 145, 550–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nishihara T., Matsuda M., Araki H., Oshima K., Kihara S., Funahashi T., Shimomura I. (2006) Effect of adiponectin on murine colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium. Gastroenterology 131, 853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takahashi T., Saegusa S., Sumino H., Nakahashi T., Iwai K., Morimoto S., Kanda T. (2005) Adiponectin replacement therapy attenuates myocardial damage in leptin-deficient mice with viral myocarditis. J. Int. Med. Res. 33, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rincón M., Enslen H., Raingeaud J., Recht M., Zapton T., Su M. S., Penix L. A., Davis R. J., Flavell R. A. (1998) Interferon-γ expression by Th1 effector T cells mediated by the p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway. EMBO J. 17, 2817–2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kaplan M. H., Sun Y. L., Hoey T., Grusby M. J. (1996) Impaired IL-12 responses and enhanced development of Th2 cells in Stat4-deficient mice. Nature 382, 174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Szabo S. J., Kim S. T., Costa G. L., Zhang X., Fathman C. G., Glimcher L. H. (2000) A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell 100, 655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsatsanis C., Zacharioudaki V., Androulidaki A., Dermitzaki E., Charalampopoulos I., Minas V., Gravanis A., Margioris A. N. (2005) Adiponectin induces TNF-α and IL-6 in macrophages and promotes tolerance to itself and other pro-inflammatory stimuli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 1254–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]