Background: Cholesterol degradation is challenging due to its complex structure and low water solubility.

Results: C25 dehydrogenase is a novel molybdenum/iron-sulfur/heme-containing enzyme that hydroxylates the tertiary C25 of the steroid side chain.

Conclusion: C25 dehydrogenase and related enzymes identified in the genome of Sterolibacterium denitrificans replace oxygenases in anaerobic and even aerobic steroid metabolism.

Significance: O2-independent hydroxylations by molybdoenzymes probably represent a general strategy to activate steroid substrates anaerobically.

Keywords: Bacterial Metabolism, Biodegradation, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Cholesterol, Steroid, Anoxic Degradation

Abstract

Cholesterol is a ubiquitous hydrocarbon compound that can serve as substrate for microbial growth. This steroid and related cyclic compounds are recalcitrant due to their low solubility in water, complex ring structure, the presence of quaternary carbon atoms, and the low number of functional groups. Aerobic metabolism therefore makes use of reactive molecular oxygen as co-substrate of oxygenases to hydroxylate and cleave the sterane ring system. Consequently, anaerobic metabolism must substitute oxygenase-catalyzed steps by O2-independent hydroxylases. Here we show that one of the initial reactions of anaerobic cholesterol metabolism in the β-proteobacterium Sterolibacterium denitrificans is catalyzed by an unprecedented enzyme that hydroxylates the tertiary C25 atom of the side chain without molecular oxygen forming a tertiary alcohol. This steroid C25 dehydrogenase belongs to the dimethyl sulfoxide dehydrogenase molybdoenzyme family, the closest relative being ethylbenzene dehydrogenase. It is a heterotrimer, which is probably located at the periplasmic side of the membrane and contains one molybdenum cofactor, five [Fe-S] clusters, and one heme b. The draft genome of the organism contains several genes coding for related enzymes that probably replace oxygenases in steroid metabolism.

Introduction

Cholesterol is one of the most abundant and ubiquitous steroids. It serves as an essential constituent of eukaryotic membranes and acts as a precursor molecule for the biosynthesis of steroid hormones, oxysterols, and bile acids. Steroids are also formed by plants (1) and some prokaryotes (2), but their degradation is mostly limited to microorganisms. Microbial degradation of the omnipresent steroids like cholesterol and the analogous plant and fungal steroids (stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, ergosterol) is an important issue of the global carbon cycle. Furthermore, microbial transformation of steroid molecules is an essential part of the biotechnological production of steroid drugs (3).

Degradation of cholesterol is challenging because of its low solubility in water (95 μg/liter, 0.25 μm) and particularly because of its complex chemical structure harboring quaternary carbon atoms and a low number of functional groups. Due to this recalcitrance, cholesterol and related steroids are used as biological markers in studying the biological origin and fate of organic compounds in geological records (4). Nevertheless, the ability to grow on cholesterol as a sole carbon source is widespread in the microbial world. Nocardia, Mycobacterium, Pseudomonas, Arthrobacter, and Rhodococcus species are well known cholesterol degrading aerobes (5), some of those bacteria being used in biotechnology (3). Under aerobic conditions, mono- and dioxygenases are involved in cholesterol metabolism. They catalyze crucial hydroxylation steps that initiate degradation of the side chain and bring about the cleavage of the sterane ring (5).

Obviously, the anoxic metabolism needs to substitute all essential O2-dependent steps by an oxygen-independent strategy to overcome the chemical recalcitrance of the molecule. This challenge prompted us to study the anoxic metabolism of cholesterol in the β-proteobacterium Sterolibacterium denitrificans (6), one of two strains that are known to grow anaerobically (but also aerobically) on cholesterol as the sole carbon source (7). In a previous work, the initial steps of this anoxic metabolism were identified (8–10) (Fig. 1). Cholesterol is converted to cholest-4-en-3-one by a bifunctional cholesterol dehydrogenase/isomerase. Cholest-4-en-3-one is further oxidized to cholesta-1,4-dien-3-one catalyzed by cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase. Both transformations show analogy to the aerobic cholesterol metabolism. Recently, similar reactions were identified in anaerobic degradation of testosterone in Steroidobacter denitrificans (11).

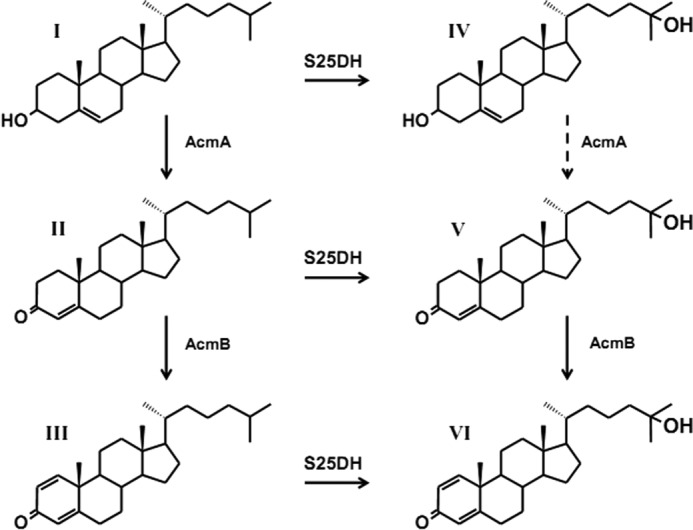

FIGURE 1.

Initial steps of anaerobic cholesterol metabolism (Acm) in S. denitrificans. AcmA, cholesterol dehydrogenase/isomerase; AcmB, cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase; S25DH, steroid C25 dehydrogenase. I, cholesterol; II, cholest-4-en-3-one; III, cholesta-1,4-dien-3-one; IV, 25-hydroxycholesterol; V, 25-hydroxycholest-4-en-3-one; VI, 25-hydroxycholesta-1,4-dien-3-one. Conversion of intermediate (IV) to intermediate (V) was not experimentally proven (dashed arrow).

Intriguingly, the following degradation of cholesterol involves an unprecedented anaerobic hydroxylation of the tertiary C25 atom of the side chain, resulting in the formation of a tertiary alcohol (10). This reaction fundamentally differs from the O2-dependent hydroxylations that occur in aerobic steroid metabolism. It is well known that in anaerobic pathways, molybdenum-containing hydroxylases can be regarded as a counterpart to oxygenases functioning in aerobic metabolism. They use water as source of the oxygen atom incorporated into the product and require an electron acceptor; in contrast, oxygenases use molecular oxygen as a source of oxygen, and many require an electron donor.

A paradigm for such an anaerobic hydroxylase acting on a hydrocarbon side chain is ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (12), and the analogous cholesterol C25 hydroxylation was proposed to be catalyzed by a similar molybdenum enzyme (10). Ethylbenzene dehydrogenase belongs to type II molybdenum-containing enzymes of the DMSO reductase family and catalyzes the hydroxylation of ethylbenzene to (S)-phenylethanol.

Here we purified and characterized steroid C25 dehydrogenase (briefly C25 dehydrogenase). The molybdenum-containing enzyme is membrane-associated, and genes coding for the subunits of the heterotrimeric enzyme were identified in the draft genome of the organism. Furthermore, analysis of the genome revealed the presence of at least seven further proteins with high similarity to the molybdenum-containing large subunit of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase and C25 dehydrogenase (hydroxylase). In contrast, no gene coding for an oxygenase acting on steroids was found in the genome. It appears indeed that several molybdenum-dependent anaerobic hydroxylases take over the role of oxygenases in the anaerobic metabolism of steroids. In this organism, the anaerobic strategy is even used for the aerobic metabolism of steroids.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Bacterial Strain

The chemicals used were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany). Sterolibacterium denitrificans Chol-1ST (DSMZ 13999) was obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany). Materials and equipment for protein purification were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and GE Healthcare.

Bacterial Cultures and Growth Conditions

S. denitrificans was grown on cholesterol at 30 °C under oxic as well as under anoxic denitrifying conditions as described (6, 9). Cells were harvested by centrifugation in the exponential growth phase at an optical density (A578 nm) of 1.0–1.6 (optical path 1 cm) and then stored at −70 °C. Large scale fermenter cultures (200 liters) were set up as described previously (10).

Preparation of Cell Extracts

Cell extracts were prepared at 4 °C under anoxic conditions. Frozen cells were suspended in 2 volumes of 20 mm Tris/H3PO4 buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.1 mg/ml DNase I. Cells were broken by passing the cell suspension through a French pressure cell (American Instruments, Silver Spring, MD) twice at 137 megapascals. The cell lysate was fractionated by two steps of centrifugation. At first, lysate was centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g to get rid of the debris, unbroken cells, and residual undissolved cholesterol. Then the supernatant (crude cell extract) was centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 2 h to separate soluble proteins from membrane-bound proteins. Extracts of aerobically grown cells were prepared under oxic conditions.

Separation of Subcellular Compartments

Steroid C25 dehydrogenase localization was studied under anoxic conditions. 50 ml of an exponentially growing culture (A578 = 1) were harvested by centrifugation at 2,800 × g for 15 min. To lyse the cells gently, the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of buffer containing 20 mm Tris/H3PO4 (pH 7.0), 1 m KCl, 10 mg/ml lysozyme (100,000 units/mg), 5 mg/ml polymyxin B, 1 mm dithioerythritol, and 0.1 mg of DNase I. The cell slurry was incubated on ice for 2 h and then centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 2 h. Supernatant containing the soluble cell proteins was separated from the pellet containing the membrane proteins. The pellet was then resuspended in buffer containing 20 mm Tris/H3PO4 (pH 7.0) and 1% Tween 20 (w/v). Both fractions were assayed for C25 dehydrogenase, cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase activities.

To separate cytoplasmic membrane from outer membrane, a sucrose gradient centrifugation was carried out. 40 ml of an exponentially growing culture (A578 = 1.4) were harvested by centrifugation at 2,800 × g for 15 min. Cells were resuspended in 2 volumes of buffer (20 mm Tris/H3PO4 (pH 7.0), 0.1 mg/ml DNase I), and disrupted by passing through the French press cell. The cell extract was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant (1.5 ml) was layered on top of a sucrose bed, consisting of 0.6 m (8 ml), 0.9 m (8 ml), and 1.75 m (8 ml) sucrose in 20 mm Tris/H3PO4 buffer (pH 7.0) and centrifuged at 38,000 rpm (100,000 × g) for 16 h (rotor 60 Ti, Beckman). Three fractions were carefully collected by removal of material from the top of the gradient: (i) the soluble protein fraction (0.6 m sucrose), (ii) the fraction containing the cytoplasmic membrane (distinct layer between 0.6 m and 0.9 m sucrose), and (iii) the outer membrane and unbroken cells (1.75 m sucrose). The collected fractions were assayed for C25 dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase activities.

In Vitro Assays

An HPLC-based C25 dehydrogenase assay was routinely performed anaerobically under a nitrogen gas phase at 30 °C. The assay mixture (0.3 ml) contained 20% (w/v) (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin, 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.5 mm cholest-4-en-3-one (from 52 mm stock dissolved in 1,4-dioxane), and 5 mm K3(Fe(CN)6). The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme, and the mixture was shaken at 700 rpm. Samples of 80 μl were taken at intervals, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 μl of 25% HCl. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000 × g, and 80 μl were analyzed for substrate and products by reverse-phase HPLC and UV detection at 240 nm. Note that the calculated hydroxylation rate based on UV detection of the product at 240 nm can be affected by further reactions of the product in cell extract, which might result in disappearance of the conjugated double bond system and therefore in absorption decrease at 240 nm. When detergent was used instead of cyclodextrin, the reaction mixture (0.3 ml) contained 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 10 mm K3(Fe(CN)6), 2.6 mm cholest-4-en-3-one, and 0.5% detergent (e.g. Tween 20, Triton X-100). The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme, and the mixture was shaken at 700 rpm. The reaction was stopped by extraction with 2 volumes of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate soluble fraction was concentrated under vacuum by a vacuum concentrator (Bachofer, Reutlingen, Germany) and analyzed by HPLC. For assaying C25 dehydrogenase in whole cells, 2 m sucrose was added to the assay mixture to avoid cell lysis.

Alternatively, purified C25 dehydrogenase was assayed spectrophotometrically with ferricenium tetrafluoroborate (FcBF4) as electron acceptor. The assay mixture (0.5 ml) contained 28% (w/v) cyclodextrin, 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.5 mm cholest-4-en-3-one, and 0.5 mm FcBF4. The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme, and the decrease of absorption caused by reduction of the ferricenium ion was followed at 300 nm (Δϵ = 3,587 m−1 cm−1). To couple substrate hydroxylation to cytochrome c reduction, oxidized bovine heart cytochrome c was used in a 40-fold molar excess to C25 dehydrogenase instead of ferricenium tetrafluoroborate. The reaction was started by the addition of 0.5 mm cholest-4-en-3-one to the reaction mixture, and the reduction of cytochrome c was followed at 550 nm (Δϵ = 20,000 m−1 cm−1) (13).

Malate dehydrogenase activity was measured at 30 °C in a reaction mixture (0.5 ml) containing 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.25 mm NADH, and 0.2 mm oxaloacetate. Oxidation of NADH was followed spectrophotometrically at 365 nm (Δϵ = 3,400 m−1 cm−1) with a filter spectrophotometer.

Cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase was assayed at 30 °C in 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5 mm 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol, 0.5 mm cholest-4-en-3-one, and 20% (w/v) cyclodextrin. The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme solution, and the mixture (0.3 ml) was shaken at 700 rpm aerobically. Samples of 80 μl were taken at intervals, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 μl of 25% HCl. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000 × g, and 80 μl were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC.

HPLC Analysis

An analytical RP-C18 column (Luna 18(2), 5 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany) was used at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min on a Waters 600 HPLC system. The mobile phase comprised a mixture of two solvents: A, 30% (v/v) acetonitrile; B, 80% (v/v) 2-propanol. The separation was performed with a linear gradient of solvent B from 15 to 80% within 20 min and additionally from 80 to 95% within 10 min. The detection of UV absorbance was performed routinely at 240 nm with a Waters 996 photodiode array detector.

Solubilization and Purification of the Enzyme

All steps for solubilization and column chromatography were performed in an anaerobic glove box with an FPLC system (P500 pump system, Amersham Biosciences) at 8 °C. The purification of C25 dehydrogenase started with solubilization of the membrane-bound protein fraction. The crude extract routinely obtained from 40 g of cells (wet mass) was centrifuged at 150,000 × g, and the membrane-bound protein fraction in the pellet was resuspended in 2 volumes of buffer containing 20 mm Tris/H3PO4 (pH 7.0). The mixture was stirred gently, and Tween 20 (70% (w/v) in H2O) was slowly added to a final concentration of 2 mg of detergent/mg of membrane protein. Then glycerol was added to a final concentration of 10% (w/v), and the solution was gently stirred for 2 h at 8 °C. After centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 2 h, the supernatant was applied onto a DEAE-Sepharose column.

A DEAE-Sepharose fast flow column (70-ml volume) was equilibrated with 10 column volumes of buffer A (20 mm Tris/H3PO4 (pH 7.0), 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.02% Tween 20). The solubilized membrane protein fraction (672 mg of protein) was applied onto the DEAE column at a flow rate of 2 ml/min, and the column was washed with 5 volumes of buffer A and then with 5 volumes of buffer B (20 mm MES/Tris (pH 6.0), 1 mm DTT, and 0.02% Tween 20) and additionally with 7 volumes of buffer B containing 50 mm KCl. The active protein pool was eluted with 1–2 volumes of buffer B containing 100 mm KCl.

A Resource Q (Amersham Biosciences) column (6 ml volume) was equilibrated with 10 column volumes of buffer A. The active protein pool after chromatography on DEAE-Sepharose column (176 mg protein) was diluted with an equal volume of buffer A and applied onto the Resource Q column at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The column was washed with 3 volumes of buffer A and then with 2 volumes of buffer B and additionally with 5 volumes of buffer B containing 50 mm KCl. The active protein pool was then eluted with 6–7 volumes of buffer B containing 75 mm KCl.

A Reactive Green 19-agarose (Sigma) column (30-ml volume) was equilibrated with 10 column volumes of buffer B. The active protein pool after chromatography on the Resource Q column (32 mg of protein) was concentrated 4-fold using centrifugal devices (Pall, MicrosepTM; 30 kDa), diluted with a 3-fold volume of buffer B, and concentrated 4-fold again to reduce the salt concentration. Then the concentrated protein pool was diluted 10-fold with buffer B and applied onto the column, which was run at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed with 3 volumes of buffer B and then with 3 volumes of buffer A, and the active protein pool was eluted with 8–10 volumes of buffer A containing 2 mm cholic acid.

A Reactive Red 120-agarose (Sigma) column (10-ml volume) was equilibrated with 10 column volumes of buffer B. The active protein pool after chromatography on the Reactive Green 19 column was concentrated 4-fold by centrifugal devices (Pall, MicrosepTM; 30 kDa), diluted with a 9-fold volume of buffer B to reduce the concentration of cholic acid, and applied onto the column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed with 2 volumes of buffer B, and the enzyme was eluted with 1 volume of 50% of buffer A. The fraction was concentrated by centrifugal devices (Pall, MicrosepTM; 30 kDa).

Preparation of Cholest-4-en-3-one-25-ol

C25 dehydrogenase assays (0.5 ml) were performed for the synthesis of cholest-4-en-3-one-25-ol. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 14 h and were then extracted with 3 volumes of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate fractions were evaporated, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.2 ml of 2-propanol and applied to a HPLC column. The peaks containing product were collected, and the solution was lyophilized. The obtained cholest-4-en-3-one-25-ol was dissolved in 0.3 ml of 1,4-dioxane, and the concentration was determined by using a calibration curve prepared with cholest-4-en-3-one.

Characterization of the Enzyme

Electron acceptor specificity of the C25 dehydrogenase was tested by using the following electron acceptors: K3[Fe(CN)6], ferricenium tetrafluoroborate, ferricenium hexafluoro-phosphate, NAD+, NADP+, phenazine methosulfate, 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol, methylene blue, and duroquinone. HPLC-based assays were set up with 5 mm each of the electron acceptor. To assess the pH optimum, C25 dehydrogenase was assayed in 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer within a pH range of 6.0–8.0. Reversibility of the C25 hydroxylation reaction was tested under anaerobic conditions in 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), containing 10 mm methyl viologen, 5 mm dithionite, and 0.1 mm cholest-4-en-3-one-25-ol. After adding the enzyme (4.5 μg), the reaction mixture was incubated for 16 h and then analyzed by HPLC. UV-visible spectra were recorded with a Cary spectrophotometer (Cary 100 Bio, Varian) by using a gas-tight stoppered quartz cuvette under anaerobic conditions. The native molecular mass of C25 dehydrogenase was determined by gel filtration on a Superdex 200 column (24-ml volume, Amersham Biosciences) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The column was equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mm Tris/H3PO4 (pH 7.0), 1 mm DTT, 500 mm KCl, and 0.02% Tween 20. For calibration, thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), bovine serum albumin (69 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), and RNase I (13.7 kDa) were used. N-terminal labeling of native C25 dehydrogenase was carried out by derivatization with (N-succinimidyloxycarbonylmethyl)tris(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl) phosphonium bromide according to Ref. 14. MASCOT MS/MS data searches were performed by using the protein database derived from the genome sequences of S. denitrificans.2

Computational Analysis

The BLASTP searches were performed via the NCBI BLAST server (15, 16). The search was performed in September 2011. The amino acid sequences of subunits of C25 dehydrogenase were used as queries for BLASTP searches against assembled bacterial genomes. Gene prediction and annotation of the draft genome were carried out using the RAST server (17) and the Geneious package version 5.4 for manual correction (18). For construction of a phylogenetic tree, the amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW implemented within MEGA4 (19). The multiple alignments were performed using ClustalW of the BioEdit package (version 7.0.9.0).

Other Methods

Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA protein quantification kit (VWR, Darmstadt) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Discontinuous SDS-PAGE was performed in 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels according to standard procedures (20). Blue native PAGE was performed in 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels according to modified standard procedures (21). Cathode buffer contained 25 mm Tris/glycine (pH 8.4) and 0.02 or 0.002%, respectively, Coomassie G250. Anode buffer contained 25 mm Tris/glycine (pH 8.4). Sample buffer contained 0.25 m Tris/Cl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, and traces of bromphenol blue. The gel was run at 8 °C and 10 mA. Gels were stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. Image Lab software (Bio-Rad version 2.0 build 8) was used for analysis of subunit composition based on their relative abundance in SDS gel. MS analysis of excised gel bands was carried out as described (22). Photometric determinations of iron and inorganic sulfide were performed by standard chemical techniques (23). Additionally, a simultaneous determination of 32 elements in the purified enzyme was performed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy using a Jarrel Ash Plasma Comp 750 instrument at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia (Athens, GA). The identification of the nucleotide moiety of the molybdenum cofactor was performed by using a Lichrospher 100 RP-18 E column (5-μm particle size, 4 × 125 mm) as described (24).

Sequences

The sequence data of new identified molybdoenzymes reported in this work have been submitted to GenBankTM and have been assigned the following accession numbers: JQ292991 (S25dA); JQ292992 (S25dB); JQ292993 (S25dC); JQ292994 (S25dA2); JQ292995 (S25dA3); JQ292996 (S25dA4); JQ292997 (S25dB4); JQ292998 (S25dC4); JQ292999 (S25dD4); JQ293000 (S25dA5); JQ293001 (S25dB5); JQ293002 (S25dC5); JQ293003 (S25dA6); JQ293004 (S25dB6); JQ293005 (S25dC6); JQ293006 (S25dA7); JQ293007 (S25dB7); JQ293008 (S25dC7); JQ293009 (EbdA-like); JQ293010 (EbdB-like); JQ293011 (EbdC-like); JQ293012 (EbdD-like).

RESULTS

C25 Dehydrogenase (Hydroxylase) Activity in S. denitrificans

An HPLC-based assay with cholest-4-en-3-one as substrate and potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) as artificial electron acceptor was developed for activity measurements in cell extracts and during purification of the enzyme. Transformation of the substrate to products was monitored routinely at 240 nm (supplemental Fig. 1). With cell extract, 25-hydroxycholest-4-en-3-one was formed as product, but in addition, cholesta-1,4-dien-3-one and 25-hydroxycholesta-1,4-dien-3-one were formed (supplemental Fig. 1B), which is due to the presence of the initial enzymes of the pathway (see Fig. 1). These initial enzymes act also on compounds I and II (Fig. 1). In contrast, purified C25 dehydrogenase produced only 25-hydroxycholest-4-en-3-one (supplemental Fig. 1C; see below). Coupling of substrate oxidation to the reduction of the artificial electron acceptor 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol or phenazine methosulfate in a spectrophotometric test could not be used with cell extracts due to nonspecific reactions occurring in extracts. A photometric assay with ferricenium cation as artificial electron acceptor, however, was developed to measure the activity of purified C25 dehydrogenase (see below). Activity was linearly dependent on the amount of added protein in the range 0–0.11 mg/ml protein and required the presence of detergents like Triton X-100, Tween 20, dodecyl β-d-maltoside, or 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (briefly cyclodextrin). Routinely, 20% (w/v) cyclodextrin was added to dissolve up to 0.7 mm of steroid substrates, and the addition of detergent or cyclodextrin resulted in a 1,000-fold activity increase. The pH optimum of the reaction was between 7.0 and 7.5. Nearly identical activities were obtained under oxic and strictly anoxic conditions, indicating that molecular oxygen is not required for the hydroxylation of the side chain. The specific hydroxylation rate in cell extract was 2 nmol/min (milliunits)/mg of protein. This value is close to the calculated cholesterol degradation rate of 3 milliunits/mg of protein, when cells were growing under denitrifying conditions with a doubling time of 44 h. Similar activities were measured in cells that were grown on cholesterol under oxic or anoxic (denitrifying) conditions. This indicates that S. denitrificans may use the same anaerobic degradation strategy both for anaerobic and aerobic growth on cholesterol. This conclusion is corroborated by genome sequencing (see below).

Subcellular Localization

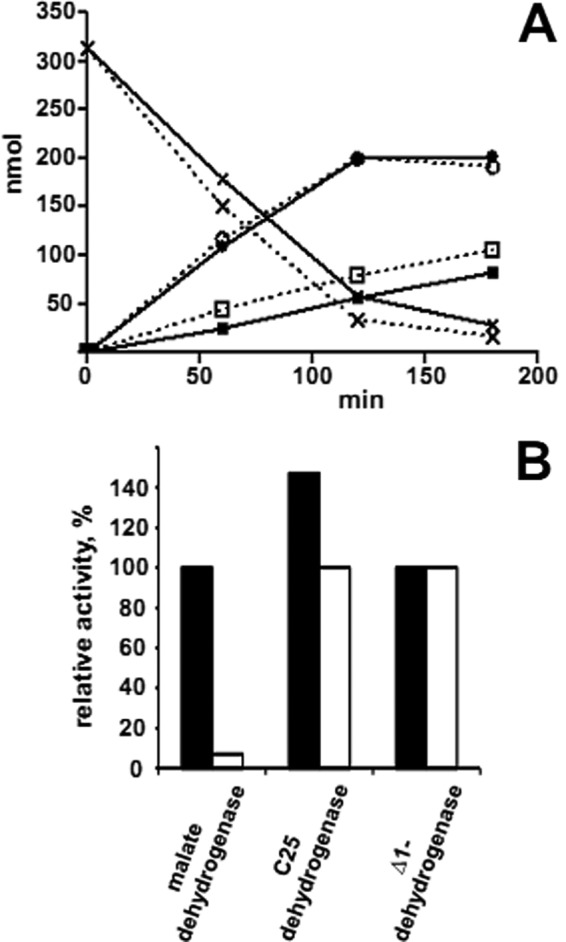

When freshly harvested cells were treated with polymyxin B and lysozyme in hypotonic medium to gently lyse the cells, formation of cell ghosts was observed by microscopic examination. After centrifugation at 150,000 × g, 60% of C25 dehydrogenase activity and 83% of cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase activity were found in the membrane fraction, whereas 90% of malate dehydrogenase activity was recovered in the soluble protein fraction. Furthermore, after centrifugation of cell extract on a sucrose gradient, C25 dehydrogenase activity was completely recovered in the cytoplasmic membrane fraction, whereas 85% of the cytoplasmic marker protein malate dehydrogenase was recovered in the soluble protein fraction. To address whether the electron acceptor site of the enzyme faces the periplasmic or cytoplasmic side, whole cell assays were carried out. Note that the cytoplasmic membrane is not permeable for charged ions like the electron acceptors potassium hexacyanoferrate or NAD+. Nevertheless, similar C25 dehydrogenase activities were measured with whole cells and with cell extract, whereas only residual activity of the cytoplasmic marker enzyme malate dehydrogenase (NAD+-dependent) was observed when tested with whole cells (Fig. 2). The addition of high concentrations (1 m) of the non-chaotropic salt NaCl to the membrane fraction did not solubilize the enzyme, whereas after treatment with Tween 20, the C25 hydroxylation activity was observed solely in the solubilized protein fraction. These observations indicate that C25 dehydrogenase is preferentially associated with the cytoplasmic membrane with the electron-accepting site facing the periplasmic space.

FIGURE 2.

Cellular localization of C25 dehydrogenase. A, C25 dehydrogenase assay with cell suspension and cell extract. The assay mixture contained 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 2 m sucrose, 7% (w/v) (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin, 0.7 mm cholest-4-en-3-one, 5 mm K3(Fe(CN)6), and 0.1 ml of cell suspension (0.3 mg of protein) or cell extract (0.3 mg of protein) in a total volume of 0.3 ml. Solid line, assay with cell suspension; dashed line, assay with cell extract. ×, conversion of cholest-4-en-3-one; circles, formation of cholesta-1,4-dien-3-one; squares, formation of 25-hydroxycholesta-1,4-dien-3-one. B, relative activities of enzymes determined in cell suspension and in cell extract. Solid bars, activities in cell extract: C25 dehydrogenase (2.2 milliunits/mg), cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase (6 milliunits/mg), and malate dehydrogenase (1 unit/mg); open bars, activities measured with suspension of whole cells: C25 dehydrogenase (1.5 milliunits/mg), cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase (6 milliunits/mg), and malate dehydrogenase (72 milliunits/mg).

Purification

The membrane-bound protein fraction was used for purification, yielding a brownish enzyme preparation. Routinely, the soluble protein fraction after Tween 20 treatment was not used further; it contained ∼40% of total C25 dehydrogenase activity and can be used for enzyme purification following the same scheme. The solubilization of membrane-bound protein was performed with the weak detergent Tween 20, which is commonly used for solubilization of peripheral membrane proteins. After solubilization, about 95% of the activity was obtained in the solubilized protein fraction, whereas only residual activity could still be observed in the membrane fraction. A nearly homogeneous C25 dehydrogenase fraction containing three subunits was obtained after four chromatographic steps (Fig. 3A and supplemental Table 1). Two chromatographic steps were carried out on DEAE and Resource Q anion exchange columns, followed by two affinity chromatographic steps using Reactive Green 19 and Reactive Red 120. C25 dehydrogenase was eluted from Reactive Green 19 by the substrate analog cholic acid, whereas a pH shift was used for its elution from Reactive Red 120. Although the enzyme activity was not affected by oxygen in cell extracts, after the first chromatographic DEAE step, the enriched fraction quickly lost activity in air. Therefore, purification had to be carried out under anoxic conditions.

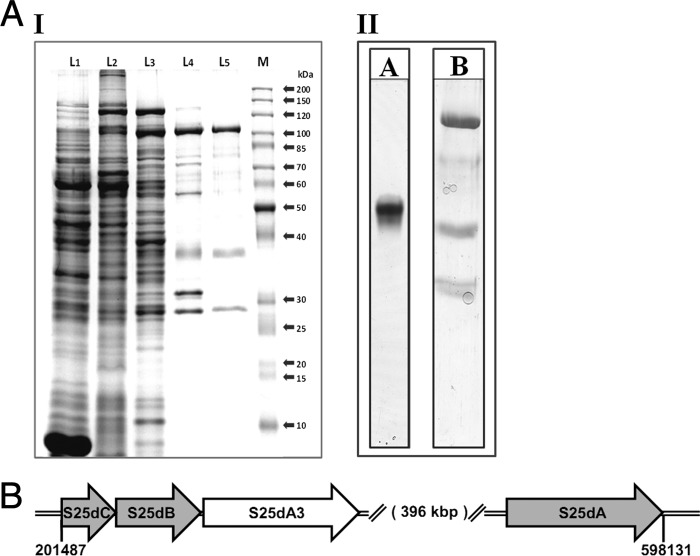

FIGURE 3.

Purification and characterization of C25 dehydrogenase. A, SDS-PAGE (11%) of active pools during purification of C25 dehydrogenase (I) and blue native PAGE of the purified enzyme (II). I, L1, cell extract (100 μg of protein); L2, solubilized membrane fraction (100 μg of protein); L3–L5, active pools after chromatography on DEAE (L3; 34 μg of protein), on Resource Q (L4; 20 μg of protein), and on Reactive Red 120 (L5; 6 μg of protein); lane M, marker proteins (sizes given on the right). II, lane A, blue native PAGE (8%) of enzyme after Reactive Red 120 chromatography (9 μg). Lane B, the visible band was cut out, treated with SDS-buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (11%). Proteins were stained with sensitive Coomassie Blue. B, organization of genes encoding C25 dehydrogenase and C25 dehydrogenase-like enzyme in S. denitrificans. S25dA, α subunit of C25 dehydrogenase; S25dB, β subunit of C25 dehydrogenase; S25dC, γ subunit of C25 dehydrogenase; S25dA3, molybdenum-containing subunit of a C25 dehydrogenase-like protein of unknown function.

Molecular Properties

Steroid C25 dehydrogenase consists of three subunits of ∼108, 38, and 27 kDa, as revealed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). The subunits were present in an approximate 1:1:1 molar ratio. The molecular mass of the native enzyme was determined by gel filtration as 168 ± 12 kDa, indicating a αβγ-composition. Based on peptide mass fingerprint analysis of gel bands, the corresponding genes were identified in a draft genome of the organism (Fig. 3B).2 The gene for the α subunit was a single ORF related to the large subunit of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, which contained a 5′ sequence coding for an N-terminal twin arginine translocation (Tat) leader peptide. In contrast, the genes for the β and γ subunits were located 396 kbp away in a cluster of three genes coding for α, β, and γ subunits of another molybdenum-containing enzyme also related to ethylbenzene dehydrogenase. Apparently, the β and γ subunits are shared by these two similar molybdenum enzymes, one being C25 dehydrogenase and the function of the other being unknown. The phenomenon of subunit sharing may be common in this metabolic pathway (see “Discussion”). The calculated sizes of the subunits were 108 kDa (α), 38 kDa (β), and 23 kDa (γ). The reason for the apparent larger size of the γ subunit estimated by SDS-PAGE may be due to hydrophobicity of this putative membrane anchor protein.

Edman degradation for N-terminal amino acid sequencing of the proteins after blotting on a PVDF membrane or electroelution out of SDS-polyacrylamide gels was not successful. This failure could be caused by blocking of the α-amino group. The N-terminal amino acid of the α subunit could, however, be derivatized with (N-succinimidyloxycarbonylmethyl)tris(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl) phosphonium bromide. After mass spectrometric detection of labeled peptides, the tris(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl) phosphonium bromide label was identified on the methionine of the large subunit, corresponding to the first amino acid coded by the gene. Surprisingly, in this enzyme preparation the N-terminal leader peptide of the α subunit apparently was not cleaved off. No tris(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl) phosphonium bromide label could be identified on the β and γ subunits, indicating that they were probably not accessible for derivatization.

The molar contents of molybdenum, iron, and acid-labile sulfur were determined. The molybdenum content was 0.7 ± 0.1 mol/mol of enzyme, as determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy; the iron content was 16 ± 5 mol/mol of enzyme as determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy and colorimetric assay; and the acid-labile sulfur content was 18 ± 5 mol/mol of enzyme. These values are consistent with the predicted presence of one molybdenum atom, four [Fe4S4] clusters and one [Fe3S4] cluster, and one heme. Analysis of the nucleotide part of molybdenum cofactor revealed the presence of GMP rather than AMP or CMP.

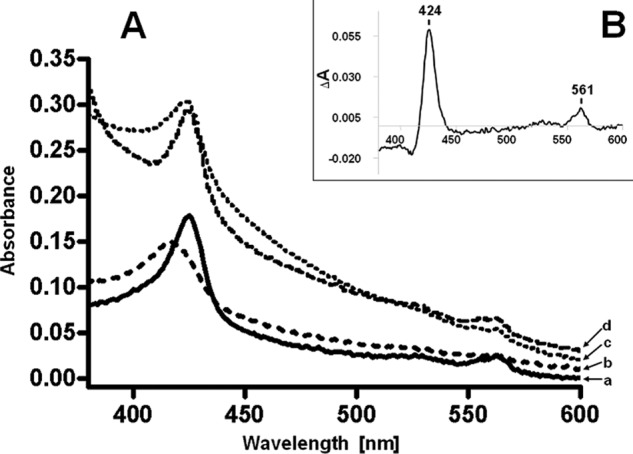

Spectral Properties

The complex UV-visible spectrum of the purified brownish enzyme showed distinct absorption maxima at 424, 527, and 561 nm, which indicated the presence of a reduced heme b cofactor, as well as a broad shoulder around 400 nm. Anaerobic oxidation of the enzyme with potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) resulted in the disappearance of α and β peaks of the heme at 561 and 527 nm and the shift of the Soret band at 424 nm to 416 nm (Fig. 4A). The difference spectrum of reduced minus oxidized enzyme indicated the presence of a heme b cofactor (Fig. 4B). The spectrum of the reduced enzyme could be restored by the addition of the substrate cholest-4-en-3-one to the cyanoferrate-oxidized enzyme (Fig. 4A). The substrate-reduced enzyme and the enzyme as isolated showed identical heme b spectra, suggesting that C25 dehydrogenase was purified in the reduced heme form. Further treatment of the enzyme with dithionite did not result in further reduction of the heme cofactor but resulted in further bleaching of the absorption between 400 and 500 nm (Fig. 4A), which is indicative of the presence of iron-sulfur clusters. Obviously, these clusters are not fully reduced by the substrate and need a strong chemical reductant, such as dithionite, in order to be entirely reduced. The heme content of the enzyme was determined as 1.13 mol/mol of protein from dithionite-reduced enzyme, using a molar absorption coefficient ϵ556 nm of 34,700 m−1 cm−1 for the α band (25).

FIGURE 4.

UV-visible spectrum of C25 dehydrogenase. A, spectrum of purified enzyme (0.9 mg/ml). a, directly after purification under anaerobic conditions; b, after anaerobic oxidation with 170 μm potassium hexacyanoferrate; c, after rereduction with 50 μm cholest-4-en-3-one dissolved in dioxane; d, after vigorous reduction with dithionite. For better visibility, spectra b–d were offset along the y axis (+0.01, +0.02, and +0.03, respectively). B, difference spectrum of the reduced enzyme (a in A) minus potassium hexacyanoferrate-oxidized enzyme (b in A).

Catalytic Properties

The purified enzyme catalyzed the hydroxylation of the tertiary C25 atom of the steroid side chain. The low water solubility of the substrates, which required the addition of detergents or cyclodextrin, hampered the determination of kinetic properties of C25 dehydrogenase. An HPLC-based assay or a photometric assay containing the ferricenium cation as an artificial electron acceptor was used to measure the activity of the purified enzyme in the presence of cyclodextrin. The substrate routinely used was cholest-4-en-3-one (supplemental Fig. 1A). Only 25-hydroxycholest-4-en-3-one was formed (supplemental Fig. 1C). The stoichiometry was 1 mol of C25 hydroxylated product formed per 1.8 mol of ferricenium added. The addition of water-soluble organic solvents like 1,4-dioxane or dimethyl sulfoxide to the reaction mixture to increase the solubility of the substrates resulted in a strong decrease of the enzymatic activity. The addition of detergents or cyclodextrin to the assay resulted in 1,000-fold increased activity.

A specific activity of 220 nmol/min/mg was found with cholest-4-en-3-one as substrate at an optimal pH value of 7–7.5 and in the presence of cyclodextrin; this activity is in the same range as that reported for ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (12). A slightly higher hydroxylation rate was observed with cholesta-4,6-dien-3-one, whereas lower activity was observed with cholesterol, cholest-5-en-3β-ol-7-one, and cholcalciferol (Table 1). No activity could be measured with ergosterol, desmosterol, or cholesterylbenzoate; the enzyme also did not act on isoamylbenzoate, isoamyl alcohol, or 2-methylbutane that mimic the branched side chain of the steroids. The potential of C25 dehydrogenase to catalyze the reverse reaction was tested by an anaerobic enzyme assay with reduced methyl viologen as electron donor and cholest-4-en-3-one-25-ol as substrate; no reduction to cholest-4-en-3-one was detected. The enzyme was not inhibited by sodium azide or sodium cyanide (5 mm each).

TABLE 1.

Relative activity of C25 dehydrogenase with steroid substrates

For structures of cholesterol, cholest-4-en-3-one and cholesta-1,4-dien-3-one, see Fig. 1. Measurements of relative activities were carried out in spectrophotometric assays. For steroid substrates, also HPLC assays were performed. No activity was observed with isoamylbenzoate, isoamylalcohol, 2-methyl-butane, ergosterol, desmosterol, and stigmasterol. For MS analysis, the assay mixture (0.5 ml) was extracted with 3 volumes of ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate was evaporated, and the dry residue was dissolved in 100 μl of chloroform. Electrospray ionization mass spectra were recorded with an Applied Biosystems API 2000 triple quadrupole instrument running in positive ion mode. ND, not determined.

| Substrate | m/z | Relative activity | Product m/z |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||

| Cholest-4-en-3-one | 385a (M + H) | 100 | 401a (M + H) |

| Cholesta-4,6-dien-3-one | 383a (M + H) | 127 | 399a (M + H) |

| 5-Cholesten-3β-ol-7-one | 401a (M + H) | 15 | 417a (M + H) |

| Cholesterol | 369b (M + H − H2O) | 10 | 367b (M + H − 2 H2O) |

| Cholecalciferol | ND | <5c | ND |

a Analysis with HPLC-electrospray ionization-MS.

b Analysis with HPLC-electrospray ionization-MS with atmospheric pressure photo ionization source.

c Formation of the product was observed using the HPLC assay when the reaction mixture was incubated for 12 h.

The capability of bovine heart cytochrome c to serve as an electron acceptor was tested in a modified spectrophotometric assay. Cytochrome c was indeed reduced, the specific enzyme activity being 20 nmol/min/mg with cholest-4-en-3-one as a substrate, which is 10-fold lower than with hexacyanoferrate (III). The Km value for bovine heart cytochrome c was estimated as 15 μm.

Stability

The activity of C25 dehydrogenase was not affected by aerobic preparation of cell extracts, whereas the purified enzyme was inactivated irreversibly by incubation in air with a half-life of 14 min (supplemental Fig. 2). The inactivation was largely prevented by the addition of the artificial electron acceptor potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) to the enzyme preparation. In the presence of cyanoferrate, more than 90% of the enzyme activity was retained after a 2-h incubation in air; still, the enzymatic activity was completely lost after 24 h of incubation. The enzyme can be stored for at least 3 months at 4 °C under anaerobic conditions.

Sequence Analysis and Phylogeny

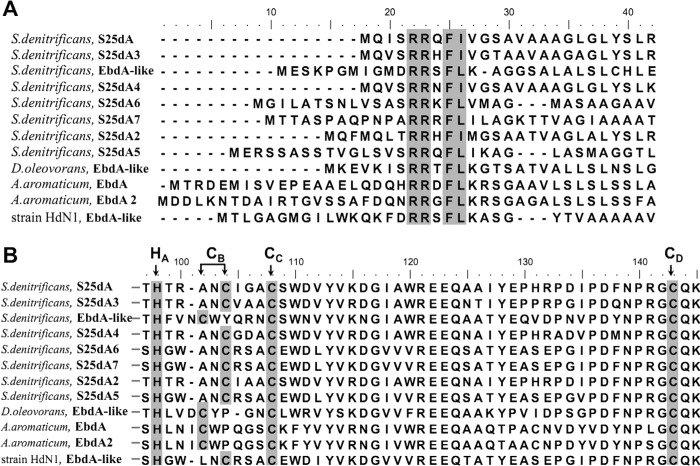

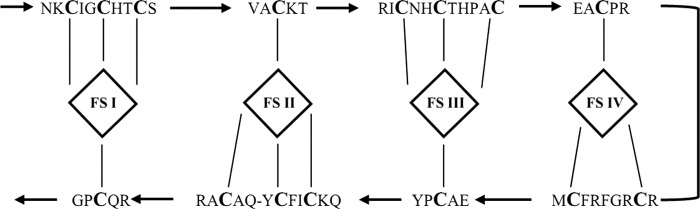

Analysis of the α subunit of C25 dehydrogenase showed high similarity to the α subunit of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase of Aromatoleum aromaticum (35% amino acid sequence identity, accession number CAI07432), an unidentified molybdopterin oxidoreductase of Desulfococcus oleovorans strain Hxd3 (35% amino acid sequence identity, accession number ABW66004), and further molybdopterin-containing oxidoreductases of the type II group of the DMSO reductase family. Examination of the N terminus of the α subunit revealed that it contained a “twin arginine” motif, MQISRRQFIV (Fig. 5), indicative of proteins that bind a prosthetic group and fold in the cytoplasm, before the translocation via the Tat system (26). Furthermore, a cysteine-rich motif, GTHTRANCIGACSWDV26NPRGCQK, was identified in the N-terminal part of the large subunit (Fig. 5). This motif is characteristic of type II enzymes with an aspartate molybdenum ligand in the active site and is responsible for coordination of a [Fe4S4] cluster (27). The β subunit showed high similarity to the β subunit of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (55% amino acid sequence identity) and to further iron-sulfur subunits of DMSO reductase-like proteins. Sequence analysis revealed conserved cysteines (Fig. 6 and supplemental Fig. 4), which are responsible for coordination of four [Fe-S] clusters (28). Analysis of amino acid sequence of the γ subunit showed similarity exclusively to the γ subunit of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase and ethylbenzene dehydrogenase-like proteins. Highly conserved methionine (Met-111) and lysine (Lys-203) residues were identified (supplemental Fig. 5), which are the axial ligands of the heme b iron in ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (29). Furthermore, neither azide nor cyanide inhibit the C25-hydroxylase. This finding supports the assumption that the heme is hexacoordinated.

FIGURE 5.

Sequence alignment of the molybdenum-containing subunit of C25 dehydrogenase from S. denitrificans, of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase from A. aromaticum, and of related enzymes. A, alignment of the N-terminal sequences bearing a consensus motif for the Tat export way. The conserved amino acids are highlighted. B, alignment of the sequence surrounding the [Fe4S4] cluster, which is characteristic of type II enzymes of the DMSO reductase family. Highly conserved amino acids coordinating this FS0-[Fe4S4] cluster are highlighted. S25dA, α subunit of C25 dehydrogenase; EbdA, α subunit of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase; S25dA2–S25dA7, molybdenum-containing subunits of enzymes with high similarity to C25 dehydrogenase, which were identified in the genome of S. denitrificans.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of amino acid sequence of β subunit of C25 dehydrogenase. Coordination of the FS1–FS4 [Fe-S] clusters in the β subunit of C25 dehydrogenase, as proposed based on the sequence similarity to ethylbenzene dehydrogenase β subunit (EbdB) and the crystal structure of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase.

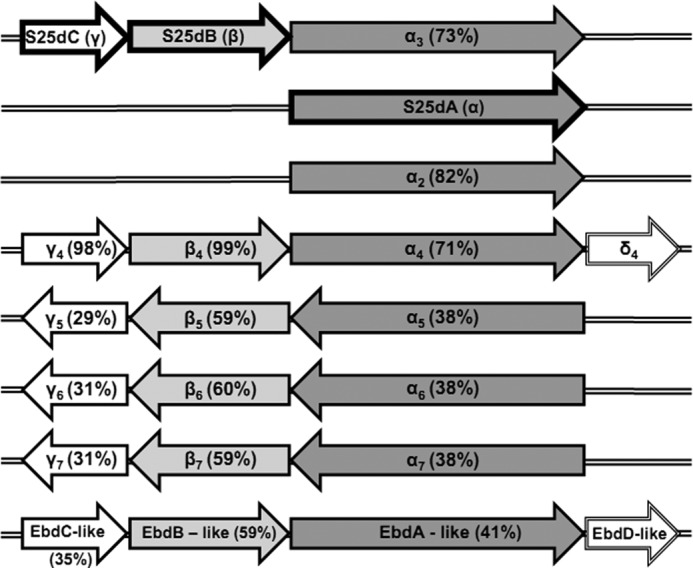

Genes Coding for Steroid C25 Dehydrogenase-like Enzymes in the Genome

S. denitrificans harbors a set of genes coding for at least seven further C25 dehydrogenase-like enzymes (Fig. 7), which are scattered in the genome. Genes of six C25 dehydrogenase-like enzymes are organized in gene clusters coding for α, β, and γ subunits, whereas an additional gene for a single α subunit is located as a single ORF, like the single gene for the α subunit of steroid C25 dehydrogenase (Fig. 7). Interestingly, only two genes encoding maturation chaperones were identified in the draft genome. Maturation of complex molybdoenzymes requires enzyme-specific chaperones for correct insertion of co-factors before folding and translocation across the membrane. The private chaperone genes often occur in the gene clusters of respective molybdoenzyme, as was shown for all type II enzymes (30–33). In contrast, the two maturation chaperones identified in the genome of S. denitrificans may be responsible for the maturation of eight molybdoenzymes.

FIGURE 7.

Genes coding for C25 dehydrogenase and C25 dehydrogenase-like enzymes in the genome of S. denitrificans. Amino acid sequences of α, β, and γ subunits of C25 dehydrogenase were used as queries for BLASTP searches against the genome of S. denitrificans. The BLASTP (2.2.14) search tool implemented into the RAST server was used. S25dA, molybdenum-containing α subunit of steroid C25 dehydrogenase; S25dB, [Fe-S] clusters-containing β subunit of steroid C25 dehydrogenase; S25dC, heme b-containing γ subunit of steroid C25 dehydrogenase; α2–α7, genes coding for molybdenum-containing subunits related to S25dA; β4–β7, genes coding for [Fe-S] cluster-containing subunits related to S25dB; γ4-γ7, genes coding for heme b-containing subunits related to S25dB; δ4, EbdD-like, genes coding for proteins related to maturation chaperone of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase. EbdABC-like, molybdenum-containing enzyme related to S25dABC but phylogenetically clustering with ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (Fig. 8). The sequence identities to the corresponding subunits of C25 dehydrogenase are given in parentheses.

Interestingly, no gene resembling any oxygenase gene from the known aerobic steroid metabolism could be found. This is another argument for the functioning of the O2-independent steroid pathway studied here, both under anoxic and oxic conditions.

DISCUSSION

Function of C25 Dehydrogenase

Previous studies showed that under anoxic conditions, cholesterol is transformed to cholest-4-en-3-one and cholesta-1,4-dien-3-one (Fig. 1) (11). These transformations are similar to those occurring in aerobic steroid degradation (5). Here we described a novel molybdenum-containing enzyme that catalyzes the subsequent anaerobic hydroxylation of the C25 tertiary carbon atom of the steroid side chain. It acts as counterpart to C26 monooxygenase of aerobic catabolism (34) that exploits the ability of activated molecular oxygen to overcome the high C–H bond stability. C25 dehydrogenase resembles ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, which catalyzes a similar oxygen-independent hydroxylation of a hydrocarbon, forming secondary alcohols of a wide range of aromatic and heterocyclic compounds with an ethyl or propyl moiety (12). Hydroxylation may proceed via formation of a carbocation, which is stabilized by an adjacent aromatic ring (35). Because of the high similarity of C25 dehydrogenase with ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, we assume that C25 dehydrogenase employs a similar hydroxylation mechanism. Due to the higher stability of the C25 carbocation compared with the terminal C26 or C27, its hydroxylation is probably favored.

S. denitrificans is a facultative anaerobic cholesterol degrader. It appears that the same anaerobic strategy is used under anoxic and oxic conditions, as indicated by the following findings. (i) Comparable anaerobic C25 hydroxylation activities were measured in extracts of anaerobically and aerobically grown cells. (ii) Previous proteome analyses revealed no differences in soluble protein patterns of anaerobically and aerobically grown cells (9). (iii) No oxygenase genes known from aerobic cholesterol metabolism could be identified in the draft genome of the organism. The usage of one common anaerobic strategy is highly economical for an organism growing on steroids both under anoxic and oxic conditions. It reflects an adaptation of a facultative anaerobic organism to frequent periodical oxygen fluctuations allowing the instantaneous usage of cholesterol, no matter whether oxygen is available or not. Apparently, the enzymes of the anaerobic strategy are sufficiently oxygen-stable in vivo and possibly also in cell extracts, although purified C25 dehydrogenase is oxygen-labile.

Membrane Association and Catalysis at Lipid-Water Interface

C25 dehydrogenase operates on highly hydrophobic substrates, which, due to their low water solubility, probably concentrate in the membrane bilayer rather than in the aqueous phase of the cytoplasm. Thus, a membrane-associated C25 dehydrogenase can easily reach the hydrophobic side chain of its substrate (36), which may provide kinetic advantages because both enzyme and its substrate are concentrated within the membrane. A similar situation was described for cytochrome P-450scc, a mono-oxygenase cleaving the side chain of cholesterol and forming pregnenolone. C25 dehydrogenase may partially immerse into the membrane bilayer, thus facilitating the binding of cholesterol (37).

C25 dehydrogenase operates at the lipid-water interface on lipophilic substrates; sequence analysis does not predict transmembrane helices. All attempts to establish an in vitro assay failed when cholest-4-en-3-one was simply added to the assay. However, the activity increased 1,000-fold when detergents or cyclodextrin were added to the reaction mixture. The ability of detergents to increase activity is well known for enzymes operating on hydrophobic substrates. The phenomenon of interfacial activation was described for lipases (38), whereas the detergent-dependent activation of tyrosinase (39) or pyruvate oxidase (40) is thought to be caused by protein-detergent interaction. We suggest that the activation effect on C25 dehydrogenase is caused by increased substrate solubility rather than protein-detergent interaction because a comparable stimulation of C25 hydroxylation activity was achieved both with detergents and cyclodextrin.

Electron Acceptor

The estimated redox potential of the C25-hydroxycholesterol/cholesterol pair is around +30 mV, based on theoretical calculations of related alcohol/hydrocarbon couples. Steroid C25 dehydrogenase shows in vitro activity only with artificial electron acceptors of high redox potential, like cyanoferrate (E°′ = + 420 mV) or ferricenium ion (E°′ = + 380 mV). The difference in redox potential of the substrate/product pair and that of the electron acceptor may explain the irreversibility of the reaction under experimental conditions. Due to the accessibility of the electron acceptor site of C25 dehydrogenase from the periplasmic space, a periplasmic c type cytochrome of similar positive redox potential may function as natural electron acceptor, coupling C25 hydroxylation to nitrate reduction or alternatively to O2 reduction. The use of cytochrome c was also proposed for the closely related ethylbenzene dehydrogenase from A. aromaticum (12). Bovine heart cytochrome c, tested here, is probably a poor surrogate for the bacterial cytochrome c.

Substrate Specificity

Steroid C25 dehydrogenase catalyzes the hydroxylation of cholesterol but also of intermediates II and III (Fig. 1). Apparently, the first steps of anaerobic degradation of cholesterol proceed randomly via independent reaction steps operating in parallel on the side chain and the ring system. A similar situation is known to exist for aerobic steroid degradation (5). Thus, it appears to be a general strategy of microbial steroid decomposition to follow a branched route of reactions. The hydroxylation rate of cholesterol was lower compared with that of cholest-4-en-3-one or cholesta-4,6-dien-3-one (Table 1), all substrates having the same side chains but differing in the ring systems (supplemental Fig. 3). The presence and localization of double bonds have an impact on the conformation of the molecule. Thus, the more planar conformations of rings A and B of cholest-4-en-3-one and cholesta-4,6-dien-3-one may result in a better fitting into the active site of the enzyme. No hydroxylation activity was observed with stigmasterol and ergosterol, whose side chain structures differ from that of cholesterol (supplemental Fig. 3). They harbor additional methyl or ethyl substituents at C24 that may cause steric hindrances in the active site. Therefore, we assume that C25 dehydrogenase operates selectively on the isooctane side chain of steroids and requires a tertiary C25.

One may ask whether there is a physiological reason for the preference of cholest-4-en-3-one as substrate. It is well known that cholesterol is an important constituent of eukaryotic membranes. However, steroids can affect the growth of some microorganisms, damaging their cytoplasmic membranes (e.g. the presence of cholest-4-en-3-one is toxic for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (41)). Therefore, a higher C25 transformation rate of 3-ketosteroids may reflect an adaptation of S. denitrificans to remove toxic intermediates from the membrane. Hydroxylation at C25 increases the water solubility of the molecules, thus facilitating migration out of the membrane (42).

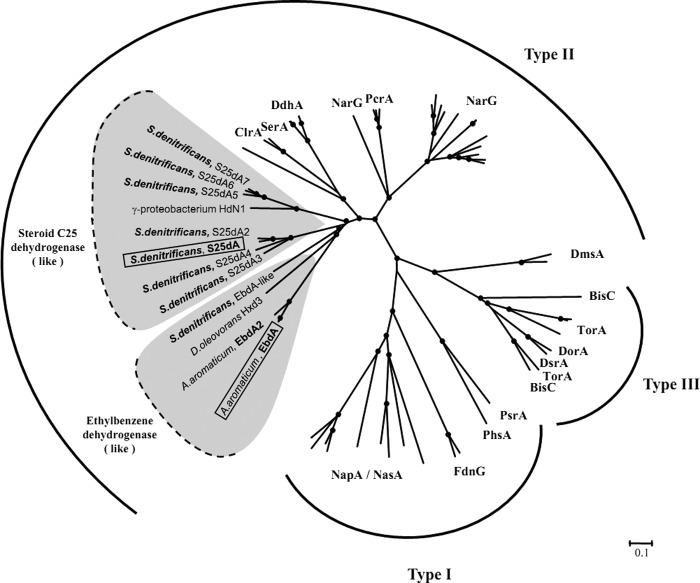

C25 Dehydrogenase, a New Member of the DMSO Reductase Family of Molybdoenzymes

Steroid C25 dehydrogenase is a molybdenum/iron-sulfur/heme-containing enzyme and belongs to type II of the DMSO reductase family enzymes. Based on its high sequence similarity to ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (29) and other archetypal complex iron-sulfur-molybdoenzymes (28), the α subunit contains molybdenum coordinated by molybdo-bis(pyranopterin guanine dinucleotide) cofactor and the FS0-[Fe4S4] cluster (Fig. 5B); the β subunit harbors FSI-FSIII-[Fe4S4] and FSIV-[Fe3S4] clusters (Fig. 6), and the γ subunit contains the heme b group with conserved methionine and lysine axial ligands. Remarkably, the genome of S. denitrificans harbors genes coding for at least seven further C25 dehydrogenase-like enzymes (Fig. 7). The large subunits of all of them possess a signal peptide for Tat-dependent translocation (Fig. 5A) and therefore may be located in the periplasmic space. A phylogenetic tree (Fig. 8) reveals that steroid C25 dehydrogenase and related enzymes form a distinct clade, together with other heterotrimeric, periplasmic enzymes like ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, selenate reductase, dimethylsulfide dehydrogenase, and chlorate reductase.

FIGURE 8.

Phylogenetic tree of enzymes of the DMSO reductase family (types I, II, and III) based on amino acid sequences of molybdenum-containing α subunits. C25 dehydrogenase and several related enzymes in S. denitrificans belong to family II, as do ethylbenzene dehydrogenase from A. aromaticum and related dehydrogenases. The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm. Bootstrap values higher than 75% are marked with dots. The scale bar represents 0.1 changes/amino acid. GenBankTM accession numbers for sequences used to construct the tree are listed in supplemental Table 2. BisC, biotin sulfoxide reductase; ClrA, chlorate reductase; DdhA, dimethylsulfide dehydrogenase; DmsA/DorA/DsrA, dimethylsulfoxide reductase; EbdA, ethylbenzene dehydrogenase; FdhG, formate dehydrogenase; NarG, respiratory nitrate reductase; NapA, periplasmic nitrate reductase; NasA, assimilatory nitrate reductase; PcrA, perchlorate reductase; PhsA, thiosulfate reductase; PsrA, polysulfide reductase; SerA, selenate reductase; TorA, trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase.

A signature of all type II enzymes is the presence of the FS0-[Fe4S4] cluster in the catalytic subunit, which is coordinated by an N-terminal consensus sequence (CA/HA)X2–3CBX3CCX27–34CDX(K/R) (27). So far, ethylbenzene dehydrogenase represents an exception with a HAX3CBX5CCX34CDXK consensus sequence. Interestingly, the consensus sequence of C25 dehydrogenase and related enzymes of S. denitrificans also differs from that of the other type II enzymes (Fig. 5B). Ethylbenzene dehydrogenase and C25 dehydrogenase act on hydrophobic substrates, in contrast to other type II enzymes that are involved in anaerobic respiration. The identified differences in the consensus sequence may represent a signature of the new clade of type II enzymes.

Molybdenum Hydroxylases as Counterparts of Oxygenases

Degradation of cholesterol is challenging due to its complex structure and requires, therefore, several activation steps. Under aerobic conditions, this part is taken over by four oxygenases initiating the degradation of the side chain and the cleavage of the ring structures (5). In S. denitrificans growing on cholesterol both under anaerobic and aerobic conditions, molybdenum hydroxylases obviously operate as oxygenase counterparts. The presence of a set of eight C25 dehydrogenase-like enzymes supports this suggestion. These paralogous enzymes may have evolved by several gene duplication events. Molybdenum hydroxylases probably represent a general strategy of facultative microorganisms to activate hydrophobic substrates containing a sterane ring.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Müller and Volker Brecht (Universität Freiburg) for mass spectrometry measurements and Yin-Ru Chiang and Wael Ismail (Universität Freiburg) for invaluable contributions during the early stages of this work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

This article contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1–5.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) JQ292991, JQ292992, JQ292993, JQ292994, JQ292995, JQ292996, JQ292997, JQ292998, JQ292999, JQ293000, JQ293001, JQ293002, JQ293003, JQ293004, JQ293005, JQ293006, JQ293007, JQ293008, JQ293009, JQ293010, JQ293011, and JQ293012.

J. Dermer and G. Fuchs, unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1. Behrman E. J., Gopalan V. (2005) Cholesterol and plants. J. Chem. Educ. 82, 1791–1793 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bode H. B., Zeggel B., Silakowski B., Wenzel S. C., Reichenbach H., Müller R. (2003) Steroid biosynthesis in prokaryotes. Identification of myxobacterial steroids and cloning of the first bacterial 2,3(S)-oxidosqualene cyclase from the myxobacterium Stigmatella aurantiaca. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kieslich K. (1980) Industrial aspects of the biotechnological production of steroids. Biotechnol. Lett. 2, 211–217 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mackenzie A. S., Brassell S. C., Eglinton G., Maxwell J. R. (1982) Chemical fossils. The geological fate of steroids. Science 217, 491–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kieslich K. (1985) Microbial side-chain degradation of sterols. J. Basic Microbiol. 25, 461–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tarlera S., Denner E. B. (2003) Sterolibacterium denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel cholesterol-oxidizing, denitrifying member of the β-proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 1085–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harder J., Probian C. (1997) Anaerobic mineralization of cholesterol by a novel type of denitrifying bacterium Arch. Microbiol. 167, 269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiang Y. R., Ismail W., Gallien S., Heintz D., Van Dorsselaer A., Fuchs G. (2008) Cholest-4-en-3-one-Δ1-dehydrogenase, a flavoprotein catalyzing the second step in anoxic cholesterol metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 107–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chiang Y. R., Ismail W., Heintz D., Schaeffer C., Van Dorsselaer A., Fuchs G. (2008) Study of anoxic and oxic cholesterol metabolism by Sterolibacterium denitrificans. J. Bacteriol. 190, 905–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiang Y. R., Ismail W., Müller M., Fuchs G. (2007) Initial steps in the anoxic metabolism of cholesterol by the denitrifying Sterolibacterium denitrificans. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13240–13249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiang Y. R., Fang J. Y., Ismail W., Wang P. H. (2010) Initial steps in anoxic testosterone degradation by Steroidobacter denitrificans. Microbiology 156, 2253–2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kniemeyer O., Heider J. (2001) Ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, a novel hydrocarbon-oxidizing molybdenum/iron-sulfur/heme enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21381–21386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prütz W. A. (1993) Sulfane-activated reduction of cytochrome c by glutathione. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 18, 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gallien S., Perrodou E., Carapito C., Deshayes C., Reyrat J. M., Van Dorsselaer A., Poch O., Schaeffer C., Lecompte O. (2009) Ortho-proteogenomics. Multiple proteome investigation through orthology and a new MS-based protocol. Genome Res. 19, 128–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benson D. A., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D. J., Ostell J., Sayers E. W. (2011) GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D32–D37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aziz R. K., Bartels D., Best A. A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R. A., Formsma K., Gerdes S., Glass E. M., Kubal M., Meyer F., Olsen G. J., Olson R., Osterman A. L., Overbeek R. A., McNeil L. K., Paarmann D., Paczian T., Parrello B., Pusch G. D., Reich C., Stevens R., Vassieva O., Vonstein V., Wilke A., Zagnitko O. (2008) The RAST Server. Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drummond A. J., Ashton B., Buxton S., Cheung M., Cooper A., Duran C., Field M., Heled J., Kearse M., Markowitz S., Moir R., Stones-Havas S., Sturrock S., Thierer T., Wilson A. (2011) Geneious, version 5.4, Biomatters, Ltd., Aukland, New Zealand [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007) MEGA4. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schägger H., Von Jagow G. (1991) Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal. Biochem. 199, 223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramos-Vera W. H., Labonté V., Weiss M., Pauly J., Fuchs G. (2010) Regulation of autotrophic CO2 fixation in the archaeon Thermoproteus neutrophilus. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5329–5340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lovenberg W., Buchanan B. B., Rabinowitz J. C. (1963) Studies on the chemical nature of clostridial ferredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 3899–3913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sachelaru P., Schiltz E., Brandsch R. (2006) A functional mobA gene for molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide cofactor biosynthesis is required for activity and holoenzyme assembly of the heterotrimeric nicotine dehydrogenases of Arthrobacter nicotinovorans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5126–5131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanlon S. P., Toh T. H., Solomon P. S., Holt R. A., McEwan A. G. (1996) Dimethylsulfide:acceptor oxidoreductase from Rhodobacter sulfidophilus. The purified enzyme contains b-type heme and a pterin molybdenum cofactor. Eur. J. Biochem. 239, 391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berks B. C. (1996) A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol. Microbiol. 22, 393–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jormakka M., Richardson D., Byrne B., Iwata S. (2004) Architecture of NarGH reveals a structural classification of Mo-bisMGD enzymes. Structure 12, 95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rothery R. A., Workun G. J., Weiner J. H. (2008) The prokaryotic complex iron-sulfur molybdoenzyme family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 1897–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kloer D. P., Hagel C., Heider J., Schulz G. E. (2006) Crystal structure of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase from Aromatoleum aromaticum. Structure 14, 1377–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bender K. S., Shang C., Chakraborty R., Belchik S. M., Coates J. D., Achenbach L. A. (2005) Identification, characterization, and classification of genes encoding perchlorate reductase. J. Bacteriol. 187, 5090–5096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rabus R., Kube M., Beck A., Widdel F., Reinhardt R. (2002) Genes involved in the anaerobic degradation of ethylbenzene in a denitrifying bacterium, strain EbN1. Arch. Microbiol. 178, 506–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McDevitt C. A., Hugenholtz P., Hanson G. R., McEwan A. G. (2002) Molecular analysis of dimethyl sulfide dehydrogenase from Rhodovulum sulfidophilum. Its place in the dimethyl sulfoxide reductase family of microbial molybdopterin-containing enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 1575–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krafft T., Bowen A., Theis F., Macy J. M. (2000) Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding the periplasmic-cytochrome b-containing selenate reductase of Thauera selenatis. DNA Seq. 10, 365–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosłoniec K. Z., Wilbrink M. H., Capyk J. K., Mohn W. W., Ostendorf M., van der Geize R., Dijkhuizen L., Eltis L. D. (2009) Cytochrome P450 125 (CYP125) catalyzes C26 hydroxylation to initiate sterol side chain degradation in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 1031–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Szaleniec M., Hagel C., Menke M., Nowak P., Witko M., Heider J. (2007) Kinetics and mechanism of oxygen-independent hydrocarbon hydroxylation by ethylbenzene dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 46, 7637–7646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rothman J. E., Engelman D. M. (1972) Molecular mechanism for the interaction of phospholipid with cholesterol. Nat. New Biol. 237, 42–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seybert D. W., Lancaster J. R., Jr., Lambeth J. D., Kamin H. (1979) Participation of the membrane in the side chain cleavage of cholesterol. Reconstitution of cytochrome P-450scc into phospholipid vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 12088–12098 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ferrato F., Carriere F., Sarda L., Verger R. (1997) A critical reevaluation of the phenomenon of interfacial activation. Methods Enzymol. 286, 327–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wittenberg C., Triplett E. L. (1985) A detergent-activated tyrosinase from Xenopus laevis. I. Purification and partial characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 12535–12541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gennis R. B. (1977) Protein-lipid interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 6, 195–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ouellet H., Guan S., Johnston J. B., Chow E. D., Kells P. M., Burlingame A. L., Cox J. S., Podust L. M., de Montellano P. R. (2010) Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP125A1, a steroid C27 monooxygenase that detoxifies intracellularly generated cholest-4-en-3-one. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 730–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Olkkonen V. M., Hynynen R. (2009) Interactions of oxysterols with membranes and proteins. Mol. Aspects Med. 30, 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]