Background: Recent phosphoproteome data reveal the extent of post-translational phosphorylation in selected apicomplexan parasites.

Results: Binding site mutants that mimic the effect of MTIP phosphorylation in vivo severely decrease MyoA binding.

Conclusion: Phosphorylation of selected binding site residues modulates the activity of the actomyosin motor.

Significance: Study of Apicomplexa phosphosites can inform on the regulation of functions involved in pathogenesis.

Keywords: MTIP, MyoA, Plasmodium, Phosphorylation, NMR, X-ray Crystallography

Abstract

The interaction between the C-terminal tail of myosin A (MyoA) and its light chain, myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP), is an essential feature of the conserved molecular machinery required for gliding motility and cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites. Recent data indicate that MTIP Ser-107 and/or Ser-108 are targeted for intracellular phosphorylation. Using an optimized MyoA tail peptide to reconstitute the complex, we show that this region of MTIP is an interaction hotspot using x-ray crystallography and NMR, and S107E and S108E mutants were generated to mimic the effect of phosphorylation. NMR relaxation experiments and other biophysical measurements indicate that the S108E mutation serves to break the tight clamp around the MyoA tail, whereas S107E has a smaller but measurable impact. These data are consistent with physical interactions observed between recombinant MTIP and native MyoA from Plasmodium falciparum lysates. Taken together these data support the notion that the conserved interactions between MTIP and MyoA may be specifically modulated by this post-translational modification.

Introduction

Processes of cell invasion and gliding motility, including the invasion of red blood cells by merozoites, are essential in the life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum, the major causative agent of malaria in humans. The motive force for these events is provided by a dedicated actomyosin motor located under the surface membrane of the parasite (1–4). In this motor, actin filaments attached to membrane proteins bind an atypical myosin (MyoA),5 which is in turn attached by its C-terminal end to a sub pellicular structure called the inner membrane complex via a myosin light chain (or myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP)) (5, 6). MyoA, MTIP, and the 45-kDa glideosome-associated protein (GAP45) cotranslationally form a complex that interacts with other proteins such as GAP50 at the inner membrane complex (7).

The complex of MTIP and MyoA is a conserved feature among apicomplexan parasites and can be reconstituted in vitro using recombinant MTIP constructs and synthetic peptides from the C-terminal tail of MyoA (5, 6, 8). In the latest crystal structure described (9), the C-terminal MTIP residues 60–204 adopt a calmodulin-like fold with two globular domains (N-terminal domain and C-terminal domain) connected by a 5-residue linker. Each domain is composed of two EF hands, which clamp around the C-terminal 15 amino acids of Plasmodium yoelii MyoA. The MTIP construct used in this complex, solved at physiological pH, forms a more compact conformation compared with the earlier structure obtained with Plasmodium knowlesi MTIP at acidic pH (9, 10). The structure also confirms that MTIP lacks the conserved calcium binding motifs observed in typical calmodulin and myosin light chain domains. Structural changes observed in four different crystal forms suggest conformational flexibility in free MTIP, which was also observed in recent computational analysis (11).

Because inhibition of the interaction between MTIP and MyoA in vivo is expected to prevent host-cell invasion and thus disrupt the parasite's life cycle, this interaction has been suggested as a target for development of novel antimalarial compounds and chemical genetic tools. Overexpression of the C-terminal end of MyoA in extracellular Toxoplasma gondii parasites significantly attenuates invasion (12), although in vivo activity against P. falciparum using synthetic MyoA-derived peptides is not yet conclusive (8, 10). Furthermore, inhibition of parasite cell growth and gliding motility has been recently reported with small chemical fragments targeting the MTIP-MyoA interaction (13).

Previous work also suggests that the function and interactions of these proteins and others might be modulated in vivo by phosphorylation events. Phosphorylation is important in the regulation of Plasmodium motility, as shown by genetic deletion or small-molecule inactivation of calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (PfCDPK1) (14, 15). This enzyme co-localizes with the motor complex in P. falciparum merozoites and can phosphorylate MTIP and GAP45 in vitro (16), whereas inhibition of protein kinase B-like enzyme (PfPKB), which also modifies GAP45, was shown to prevent parasite invasion of red blood cells (17). Recently, proteome-wide studies have shown that MTIP, MyoA, and GAP45 are examples of a large list of proteins in P. falciparum and T. gondii that are targeted for modification (18, 19). Although thousands of phosphorylation sites have been found in hundreds of P. falciparum proteins, including several involved in host cell adhesion and invasion (19–21), detailed studies on the structural effects of these modifications are sparse.

In this work we assign backbone amide NMR chemical shifts and use them to map residues on MTIP that are critical for binding of an optimized MyoA tail peptide in solution. The structure of this complex has been solved by x-ray crystallography to reveal new interactions and rationalize thermodynamic data in atomic detail. NMR relaxation experiments reveal the free state of MTIP to be highly flexible and give insight into the different timescales of motion involved in ligand recognition and clamping of the MyoA tail. Furthermore, NMR and other biophysical methods are used to predict the drastic effect of a recently reported MTIP phosphorylation event at Ser-108. The results we present here provide a number of insights to inform the design of novel MTIP-MyoA inhibitors as well as a structural basis for what may be an important regulatory mechanism in Plasmodium parasites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of Unlabeled MTIP

Transformants of Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells, containing the plasmid pRSETA encoding PfMTIP residues Ser-61 to Gln-204 with an N-terminal His6 tag spaced by a thrombin restriction site (henceforth called MTIP), were cultured in LB broth containing 100 mg liter−1 carbenicillin. Cell culture, protein expression, and initial purification by nickel affinity chromatography were carried out according to procedures reported previously (8). The His6-tagged protein was dialyzed overnight against a buffered solution containing 20 mm Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm TCEP before treatment with thrombin (Novagen) at a ratio of 1 unit:1 mg of recombinant protein for 1 h on ice. The resulting solution was further purified by preparative size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex-75 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) with an elution buffer containing 50 mm Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl, and 1 mm TCEP. This was exchanged for the buffer reported by Bosch et al. for crystallizing the closed MTIP-MyoA complex (9), i.e. 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP.

Expression and Purification of MTIP for NMR Studies

Uniformly 15N-labeled MTIP was expressed and initially purified as reported previously (8). 13C,15N-labeled protein was prepared in the same way with 0.2% w/v d-[13C]glucose (Cambridge Isotopes) used as the sole carbon source. Further purification was achieved using size exclusion chromatography as above. The buffer used for NMR experiments contained 20 mm MOPS·OH (pH 7.0), 50 mm NaCl, 0.005% (w/v) NaN3 and 1 mm TCEP.

Production of MTIP S107E and S108E Mutants

Mutagenesis of the gene encoding PfMTIP-(61–204) in the pQE30 plasmid was carried out using standard molecular biology techniques as per the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent) to produce the single site mutants S107E and S108E (henceforth, called MTIP S107E and MTIP S108E). Expression and purification of unlabeled and 15N-labeled protein was carried out according to protocols established for the wild type protein.

Peptide Synthesis

PfMyoA peptides comprising residues 799–818 and 803–818, with a free C terminus and an acetyl cap on the N terminus, were synthesized and purified as reported previously (8).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

All ITC experiments were carried out at 303 K using a VP-ITC calorimeter (MicroCal). The cell contained ∼1.4 ml of 20 μm MTIP (WT or mutants), and PfMyoA peptides were added in 5- or 10-μl injections (from a solution in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP) until saturation. The measurements were carried out in duplicate, and control titrations of the peptides into buffer confirmed no significant heat of dilution for either sequence. Data were fit using Origin (OriginLab Corp).

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF)

Thermal stability analysis was performed with DSF (22). Experiments were carried out in 96-well real-time PCR plates with 20-μl samples containing 5 μm protein and 10× SYPRO Orange dye (Sigma). Curves were analyzed in MS Excel (Microsoft Corp.) and melting temperatures were determined using a customized GraFit plug-in (Erithacus Software).

Parasite Culture

P. falciparum parasites were maintained in human O+ erythrocytes provided by the National Blood Transfusion service. 3D7 is a cloned line derived from NF54 obtained from David Walliker at Edinburgh University (23). Parasites were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% Albumax at 3% hematocrit in gassed (90% nitrogen, 5% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide) flasks at 37 °C. For tight synchronization of parasite stages, a combination of sorbitol treatment (24) and stage-specific separation using a magnetic separator was performed (25).

Precipitation of Parasite Myosin A with Recombinant MTIP

1 ml of purified 3D7 schizonts was lysed in 10 volumes of hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mm Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 1× Complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 3500 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The insoluble fraction was washed in hypotonic lysis buffer and centrifuged as described a further two times or until there was no hemoglobin visible in the supernatant. The pellet, a membrane protein fraction, was solubilized in lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 125 mm NaCl, 25 mm Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 1× protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) and incubated on ice for 20 min. Detergent-soluble proteins were present in the supernatant after centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min. 1 ml of a 50% slurry of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) was added to the lysate followed by incubation at 4 °C for 1 h to remove proteins that interacted non-specifically with the resin.

300 μg of schizont lysate was added to the appropriate amount of recombinant MTIP or mutants thereof (1, 2, 5, 10, or 20 μg) in a final volume of 630 μl. The samples were mixed by rotation for 15 h at 4 °C. 100 μl of 50% nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose was added to each sample, and incubation continued for a further 3 h. The beads were washed with 5 × 0.5 ml of lysis buffer using empty 0.8-ml centrifuge columns (Pierce), with centrifugation for 30 s at 1200 × g. Proteins bound to the resin were eluted by the addition of 100 μl of 2× reducing LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen), samples were heated to 95 °C for 5 min and recovered from the column by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 s. For Western blot analysis, 20 μl of the samples were run on a 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel in MOPS running buffer (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with a rabbit anti-myosin A antibody (gift from Dr. J. Fordham). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) were used, and signal was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences) and Biomax MR film (Eastman Kodak Co.). For verification of MTIP loading quantities, 20 μl of the samples were run on a 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel in MES running buffer (Invitrogen), and proteins were visualized by staining with Instant Blue reagent (Expedeon).

Crystal Screening, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

The preparation of the MTIP-MyoA sample used for crystallography followed closely the method published by Bosch et al. (9), with an additional size exclusion chromatography step to ensure that the sample was homogeneous and contained exclusively monomeric protein. Three molar equivalents of the N-terminal-acetylated peptide PfMyoA-(799–818) were added to the protein to form a complex. The resulting solution was incubated overnight and concentrated to 10 mg ml−1 using a centrifugal concentrator with 3-kDa molecular weight cutoff filter.

Crystallization conditions were screened using the sitting-drop method with commercially available crystallization screens. Plates were incubated at 293 K, and crystals appeared in a number of different conditions within 72 h; several were cryo-protected in paraffin oil, mounted, and tested initially for diffracting power using a 1.542 Å monochromatic radiation source and a Saturn CCD detector (Centre for Structural Biology, Imperial College). The conditions that gave the best hits matched closely those reported previously; indeed, those that produced the crystal used for data collection contained 20% PEG3350 and 0.2 m potassium thiocyanate. Data were collected in-house at 100 K and with 1° oscillations. Data were indexed with Mosflm (26) and scaled with Scala (27). Initial phasing by molecular replacement was carried out using Phaser (28) using the structure of Bosch et al. (9) (pdb code 2QAC) as a search model. The visual inspection of resulting electron density maps and manual model building was done using COOT (29). Initial refinement was performed with REFMAC (30), and final refinement steps, including TLS parameters, were carried out with Phenix (31). supplemental Table S1 shows detailed statistics for data collection and refinement.

NMR Spectroscopy

Samples for NMR consisted of either 500 μl of protein solution in a standard 5-mm tube (Norell) or 350 μl in a microscale tube (Shigemi) and contained 10% (v/v) D2O to provide a lock signal. Spectra were recorded at 303 K on Bruker 600 MHz Avance III and Bruker 800 MHz Avance II spectrometers equipped with TCI and TXI Cryoprobes, respectively (Cross Faculty NMR Centre, Imperial College London), processed in NMRPipe (32), and visualized in NMRView (33).

The chemical shifts of 1HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13C′ were obtained from the HNCACB/CBCA(CO)NH and HNCO/HN(CA) CO experiments; the spectra were analyzed in NMRView, and assignments were made using a combination of the MARS automated assignment program (34) and an in-house assignment module (35).

Backbone amide 15N longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times and steady state heteronuclear 1H,15N nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOEs) were measured at 14.1 T. For the T1 experiment, 1H,15N correlation spectra were recorded at longitudinal relaxation delays of 50, 2500, 350, 1800, 650, 1400, 950, and 1200 ms (with duplicate measurements for 350 and 1800 ms); for the T2 experiment a Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) refocusing pulse train was applied during transverse relaxation delays of 15.33, 245.35, 30.66, 168.61, 45.98, 107.30, and 76.64 ms (with duplicate measurements for 30.66 and 168.61 ms), and the NOE spectrum used a 1H presaturation period of 5 s. T1 and T2 relaxation curves were fit to simple exponential functions using the rate analysis module in NMRView (33), and NOEs are reported as the ratio of intensities of the backbone amide peaks with and without 1H presaturation.

CPMG relaxation dispersion NMR experiments were performed at 14.1 and 18.8 T using the pulse sequences reported by Kay and co-workers (36). Spectra were recorded with refocusing CPMG pulse frequencies (νCPMG) ranging from 40 to 1600 Hz with 2 repeat measurements at a constant relaxation delay (Trelax) of 50 ms together with two control experiments recorded with no relaxation delay to give reference intensities I0 for each measurable amide resonance. Effective transverse relaxation rates R2eff were then plotted against νCPMG to generate relaxation dispersion trajectories for each static field strength according to R2eff(νCPMG) = ln{I0/I(νCPMG)}/Trelax. These plots were fitted simultaneously on a per-residue basis to a model for two-site exchange to determine Rex, i.e. the exchange contribution to R2 and kex i.e. the exchange rate between the visible and invisible states. The following models were tested: (i) no exchange, i.e. R2eff = R20, the transverse relaxation rate in the absence of an exchange term; (ii) “fast” two-site exchange, described by Luz and Meiboom (37); (iii) “slow” two-site exchange, described by Carver and Richards (38).

RESULTS

Clamping of the MyoA Tail Is Enthalpically Driven and Entropically Highly Unfavorable

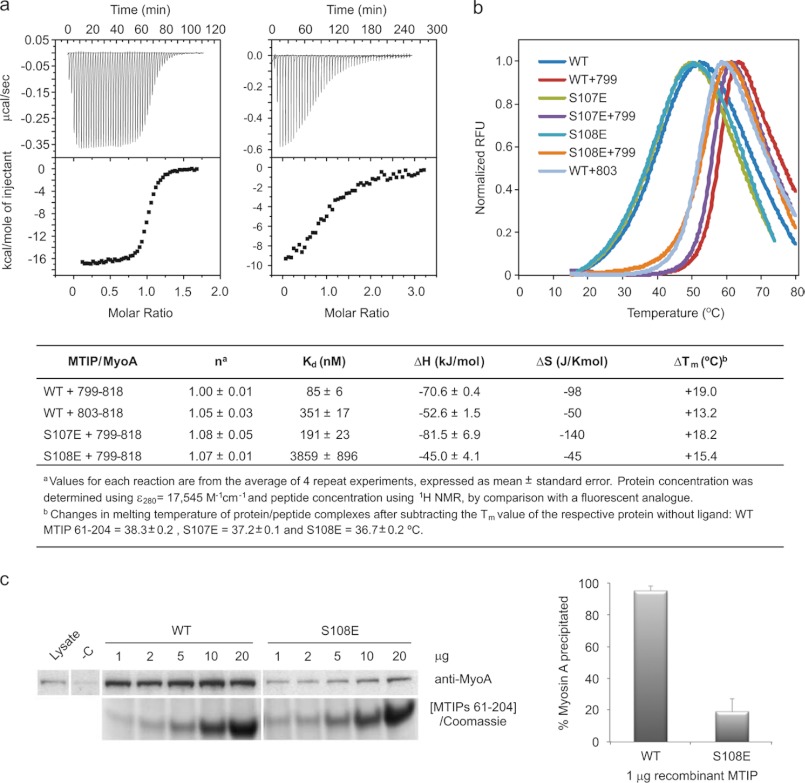

The peptide spanning the 20 C-terminal amino acids of P. falciparum MyoA (i.e. residues 799–818) was previously identified in our laboratory as a potent competitive inhibitor of a preformed complex consisting of MTIP with a fluorescent MyoA peptide (8), whereas prior crystallographic studies of this interaction used the 803–817 region of MyoA from P. yoelii as the ligand (6, 9, 10). We sought to extend our understanding of the binding thermodynamics of MTIP-MyoA by employing ITC and DSF (22) (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

Thermodynamics of MTIP-MyoA analyzed by ITC, DSF, and parasite pulldown experiments. a, shown are binding isotherms after the titration of PfMyoA tail 799–818 into a solution of MTIP (left) and MTIP S108E (center). Thermodynamic parameters fitted using Origin software (Microcal) are described in the table below. Other ITC data are shown in supplemental Fig. S1. Titrations were carried out at 303 K in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, and 1 mm TCEP. b, DSF thermograms for MTIP and MTIP mutants in free and bound forms using MyoA peptides 799–818 (799) and 803–818 (803) (right). Analysis of transition slopes is presented in supplemental Fig. S1. Changes in melting temperature (ΔTm) between free and bound forms of each protein are described in the table below. RFU, relative fluorescence units. c, shown is a Western blot analysis of MyoA pulldown assays from P. falciparum schizont lysate using a range of MTIP concentrations for the wild type protein and the phosphomimetic mutant S108E. MyoA pulldown data for S108E are shown in supplemental Fig. S1. Lysate, 6 μg of schizont lysate; represents 2% of the amount of lysate used in each sample. −C, reaction to which no recombinant MTIP was added. The histogram shows the amounts of MyoA pulled out by 1 μg of MTIP WT or the S108E mutant. Data are from the average of three independent experiments; error bars are the mean ± S.D.

ITC data show that PfMyoA-(799–818) binds to MTIP with ∼4-fold greater affinity than PfMyoA-(803–818), implying that the N-terminal extension of MyoA establishes additional native interactions that are not apparent in the previous structure of the MTIP-MyoA complex. The interaction is enthalpically driven, and interestingly, the large difference in ΔHbinding induced by the extension is partially compensated by the change in TΔSbinding (-29.5 and −15.2 kJ mol−1, respectively), giving only a modest increase in the free energy of binding compared with the shorter peptide. These observations are supported by DSF, which reveals that the complex with PfMyoA-(799–818) is significantly more stable to thermal unfolding, with an increase in Tm of 5.8 °C. In both cases we observe a large shift and sharpening of the melting transition relative to the unbound protein (supplemental Fig. S1b), as would be expected in a system where the tertiary structure of the protein may be ill-defined in the absence of its binding partner. The highly unfavorable entropy change observed by calorimetry suggests a substantial ordering upon ligand binding and is consistent with the alternative conformations of the free protein observed by x-ray crystallography (10).

Crystal Structure of MTIP with PfMyoA-(799–818) Reveals New Peptide-Protein Interactions

To explore the structural basis for changes in the binding affinity for these peptides, we sought to obtain crystallographic data of MTIP in complex with PfMyoA-(799–818). Optimization of the conditions reported previously for crystallization of PfMTIP-(60–204)/PyMyoA-(803–817) (9) yielded crystals that diffracted to 1.94 Å. Using the structure of the closed complex (pdb code 2QAC) as a search model, we were able to determine the structural model of the new complex. The coordinates of the new complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 4AOM.

The overall fold of this complex is similar to the compact structure reported previously, with both MTIP domains participating in MyoA tail binding. Residues Asn-800–Pro-802 extend the α-helix of the PfMyoA tail by an extra turn, and the side-chain of Asn-800 forms a number of water-mediated polar interactions with MTIP residues in the α-helix spanning residues Val-141–Phe-151, e.g. the backbone amide of Met-147 and the side chain of Lys-146 (supplemental Fig. S2). On the other side of the binding interface, the aliphatic side chain of Ile-801, identified previously as an important contributor to binding (8), is engaged in a hydrophobic interaction with Trp-171/Gly-172. No electron density is observed for the C-terminal Gln-818. This residue is not present in the sequence of PyMyoA, and in fact its inclusion in model peptides leads to a small decrease in binding affinity (8). Interestingly, an MTIP ion pair between side chains of Lys-71 and Asp-137, previously thought to stabilize the kinked conformation of the interdomain linker, is not observed in the new complex. Other structural details of this complex are shown in supplemental Fig. S2.

Thermodynamic Effects of Mutation at Phosphorylation Sites: S107E and S108E

Evidence of Ser-107/108 phosphorylation of MTIP in parasites is based on a monophosphorylated peptide identified from P. falciparum schizonts, but the precise site of modification could not be determined from MS/MS data due to the presence of two adjacent serines (19). To investigate the importance of this phosphorylation at a molecular level, we recreated the character of the phosphorylated residues through glutamic acid mutants S107E and S108E. From the MTIP-MyoA crystal structures and NMR data (see below), both Ser-107 and Ser-108 in the MTIP N-terminal domain form important inter- and/or intramolecular interactions, so it was expected that measurable effects on binding thermodynamics might be observed. Indeed, a drastic decrease in affinity to PfMyoA-(799–818) was observed by ITC for MTIP S108E (Kd = 3.86 μm) compared with the interaction with the wild type protein (Kd = 0.09 μm), whereas the effect with neighboring S107E was less marked (Fig. 1). DSF analysis showed that the mutants had similar thermal unfolding profiles to the WT protein in the unbound form, whereas the ΔTm values in the presence of the ligand followed the trend in binding affinities. Notably, the unfolding transition of MTIP S108E bound to MyoA-(799–818) was significantly shallower than for MTIP and MTIP S107E, suggesting a change in the cooperativity of the unfolding event as a result of a structural change in the mutant complex.

Effect of Phosphomimetic Mutations on Binding to Native MyoA

To test our hypotheses from MyoA peptide binding studies in a physiological context, we performed MyoA pulldown experiments with lysates from P. falciparum schizonts. To aliquots of parasite lysate, we titrated His-tagged MTIP and mutants (S107E and S108E) and incubated each solution with nickel resin. After a stringent washing protocol, we analyzed the amount of bound MyoA by Western blot. In the case of MTIP S108E, we observed that the amount of MyoA pulled out from the lysate was dependent on the concentration of recombinant protein, whereas in the case of MTIP, it appeared that binding was saturated even at the lowest protein concentration tested. At these MTIP concentrations (1 μg), a histogram shows that the amount of MyoA pulled out by the wild type protein is ∼5 times larger than the MyoA obtained from MTIP S108E (Fig. 1c). For MTIP S107E, binding to native MyoA was not concentration-dependent, possibly an indication that this technique is not sensitive enough to detect small changes in binding affinities, as observed for MTIP and this mutant in ITC experiments (supplemental Fig. S1). Nonetheless, these data support the observation that the weaker ITC affinities of the phosphomimetic mutants for MyoA tail peptides translate to a weaker affinity for the native, full-length MyoA protein.

NMR Assignments of Free and Bound States Enable Per-residue Analysis of MTIP in Solution

Consistent with data from fluorescence binding assays, two-dimensional NMR spectra showed large amide chemical shift changes between free MTIP and the protein in complex with PfMyoA peptides 799–818 and 803–818, indicating that ligand binding is associated with significant conformational changes. In addition, large spectral differences between these two complexes suggest additional interactions between MTIP and the 4-residue MyoA N-terminal extension (8). For the majority of MTIP amide resonances, the tight binding leads to slow exchange on the NMR chemical shift timescale between the free and bound forms of the protein. To obtain residue specific information, it was therefore necessary to acquire backbone resonance assignments of these two forms separately (Fig. 2, right). Using triple resonance NMR methods, we assigned 137 and 141 of 143 backbone amide resonances of MTIP (excluding Pro-106) for the free and PfMyoA-(799–818)-bound states, respectively.

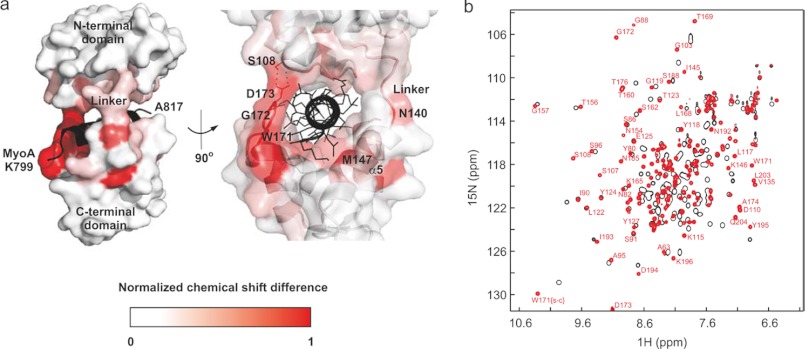

FIGURE 2.

Structure and NMR-based interaction hotspots of MTIP/PfMyoA-(799–818). a, shown is the crystal structure of MTIP (surface representation; white) in complex with PfMyoA-(799–818) (schematic representation; black), highlighting hotspots of peptide binding (red) as derived from chemical shift differences in the 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the free and bound forms of MTIP. b, shown are 1H,5N HSQC spectra of 400 μm uniformly 13C,15N-labeled MTIP recorded at neutral pH and 303 K in the absence (black) and presence (red) of 3 mol eq of PfMyoA-(799–818). The backbone amides are almost completely assigned in both cases; some of these assignments are shown for the bound form.

Chemical shift indexing of 13Cα and 13C′ Nuclei (39) (supplemental Fig. S3) for the bound form suggests that in solution all the secondary structural elements seen in the crystal structure are present with the exception of the N-terminal α-helix of MTIP, spanning residues Ile-65–Lys-71. Interestingly, the chemical shift indexing predictions of the free and bound states are comparable, in line with the observation that there is no significant change in ellipticity values in circular dichroism spectra between the two conformations (6). In addition to the large free energy change of binding obtained by ITC (−41 kJ/mol), these results strongly suggest that (a) complex formation involves reorientation and clustering of existing α-helices rather than the formation of new ones and (b) ligand binding provides a major contribution to the stability of the folded protein, as shown for other calmodulin-like domains (40).

Perturbations of backbone amide chemical shifts between the free and bound states of MTIP revealed binding hotspots of the protein in solution, which were mapped onto the structure (Fig. 2, left). The C-terminal domain shows the greatest perturbations upon binding of MyoA-(799–818), and hotspots on MTIP are found along the binding groove of the structure, mainly clustered around the region that binds the N-terminal portion of the peptide. The loop spanning residues Thr-170–Thr-176 is particularly affected by MyoA complexation, presumably due to interactions with nearby peptide side chains and intra-MTIP interactions, for example hydrogen bonding between Asp-173 and Ser-108. Interestingly, the H-bond acceptor is the backbone amide of Ser-108, a residue that could not be identified in the HSQC spectrum of free MTIP likely due to exchange broadening of the peak. However, the peak is clearly visible in the dispersed region of the spectrum for the MTIP-MyoA complex. Chemical shifts of amides in the interdomain linker are also strongly affected by the presence of the peptide; this linker acts as the “hinge” about which the two globular MTIP domains clamp the MyoA tail.

Another clear binding hotspot centers on Met-147, the backbone amide of which engages in a polar interaction with PfMyoA residue Asn-800 in the crystal structure (supplemental Fig. S2). The contribution of this region was also investigated by NMR. Using high resolution 1H,5N-HSQC and HNCACB spectra, we reassigned the PfMyoA-(803–818)-bound form of MTIP by comparing the chemical shifts of Cα and Cβ nuclei to those assigned previously for the PfMyoA-(799–818) complex, assuming that the overall fold of these proteins is essentially the same (supplemental Fig. S4). Using this method it was not possible to assign peaks from the helix spanning Val-141–Phe-151 in the dispersed region of the HSQC spectrum, suggesting that the backbone chemical shifts and/or dynamics of this helix are very different between the two complexes due to interaction with the 4-residue peptide extension.

NMR Analysis of S107E and S108E Mutants

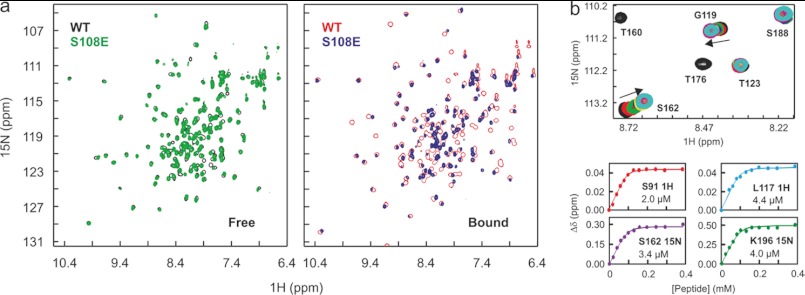

To understand more about their solution behavior relative to the wild type protein, the 15N-labeled MTIP mutants S107E and S108E were studied by NMR. In the free state, both substitutions appeared to cause minor changes relative to MTIP as judged from HSQC spectra (Fig. 3a), supporting the observations by DSF of thermal unfolding transitions. The majority of peaks overlaid well, indicating a similar overall fold. The failure to detect Ser-108 in the WT free state assignment was presumed to be due to exchange broadening, which suggests that the intramolecular H-bond with Asp-173 that stabilizes the compact structure could occur transiently in the free state. In the S108E mutant we expect that this interaction may be prevented by electrostatic repulsion, which could cause some of the changes observed. Other variations are likely due to local effects of the change to a negatively charged amino acid. Upon saturation of the S108E mutant with the MyoA tail peptide, we observed that the HSQC spectrum overlaid much less well with that of the WT bound form (Fig. 3b), indicating more substantial changes in the structure of the complex.

FIGURE 3.

NMR analysis of the MTIP S108E mutant. a, shown are overlays of 1H,15N HSQC spectra of MTIP (black and red) and MTIP S108E (green and blue) in their free state (left) and in complex with PfMyoA-(799–818) (center). b, a zoomed-in section of the titration of the MyoA tail into MTIP S108E shows some amide resonances in fast exchange (Ser-162 and Gly-119) and some in slow exchange (Thr-160 and Thr-176) with the bound state on the NMR chemical shift timescale. The overlaid spectra represent 0 (black), 0.2 (red), 0.4 (green) 0.8 (yellow), 1.3 (pink), and 3.0 (cyan) mol eq of PfMyoA-(799–818); the protein concentration was 100 μm. Those in the fast exchange regime were used to determine dissociation constants for the binding equilibrium; four curves are shown. δΔ represents the change in chemical shifts for the selected amide atoms.

To examine the dynamics of interaction with the MyoA tail, we carried out NMR titrations with 15N-labeled mutant MTIPs and unlabeled MyoA-(799–818) peptide. In the case of S107E and as observed for the WT protein, almost all shifted amide resonances fell under a slow exchange regime in which the chemical shift difference (Δω) greatly exceeds the rate of exchange (koff) between bound and free forms. This supported the tight binding observed by ITC. In the case of the MTIP S108E titration, we observed a range of exchange regimes (Fig. 3c), indicative of weaker binding overall (faster koff) but still some substantial conformational changes in certain regions of the protein (where Δω still remains greater than koff). For the amides in the fast exchange regime, we were able to track peak shifts as a function of ligand concentration and thus calculate a Kd as 2.52 ± 1.69 μm, comparable with what was measured by ITC (3.86 ± 0.90 μm).

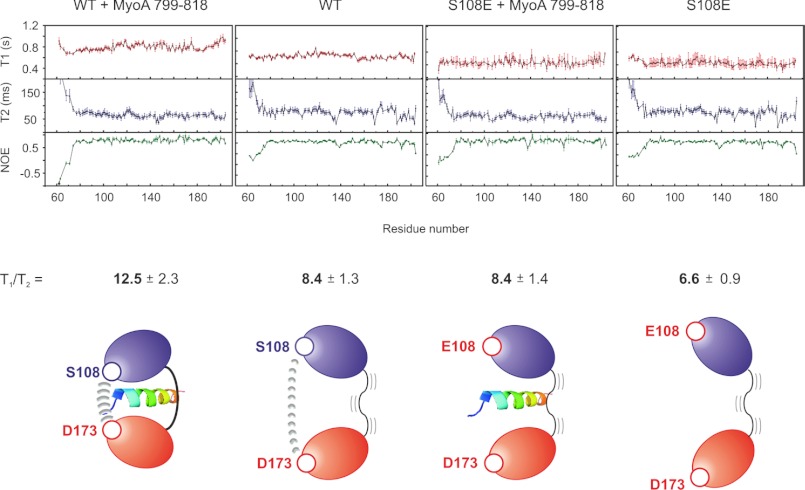

Relaxation Properties of MTIP Reveal a Highly Flexible Free State

As well as studying interaction hotspots, we were interested in exploring the per-residue dynamics of the protein, particularly in the free form for which crystallographic structural determination at physiological pH has not been possible (Figs. 4 and 5). 15N T1 and T2 relaxation times and heteronuclear 1H,15N NOEs were obtained for the backbone of free and MyoA tail-bound MTIP and plotted as a function of residue number (Fig. 5, left).

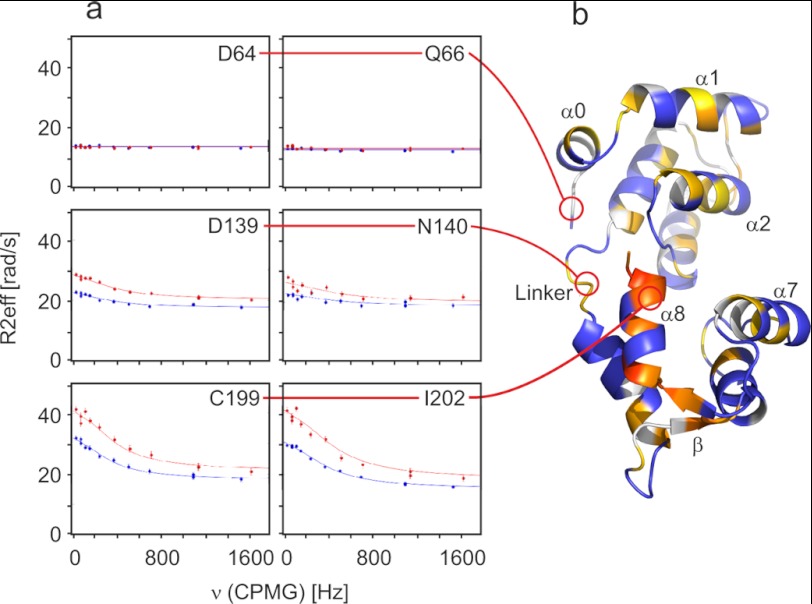

FIGURE 4.

15N CPMG relaxation dispersion NMR of free MTIP. a, shown are relaxation dispersion trajectories (R2eff versus CPMG refocusing pulse frequency) for residues from different parts of MTIP in its free state. The unstructured part of the N terminus (represented by Asp-64 and Gln-66) is highly dynamic on the ns to ps timescale but shows negligible dynamics on the slower timescales probed by the relaxation dispersion experiments, whereas the linker (represented by Asp-139 and Asn-140) and C-terminal helix α8 (represented by Cys-199 and Ile-202) appear to be undergoing exchange processes. Experimental data were obtained at neutral pH at static field strengths of 14.1 T (15N frequency of 60.77 MHz, blue) and 18.8 T (15N frequency of 81.16 MHz, red), and for those residues that exhibited exchange dynamics, data were fitted globally to models for two site exchange. b, Rex values from experiments recorded at 18.8 T are mapped onto the crystal structure of MTIP (schematic representation; white) in complex with PfMyoA-(799–818) (not included) to reveal regions of elevated ms timescale dynamics in free MTIP (white to orange gradient). Where data are missing due to overlap or excessive line broadening, residues are colored in blue.

FIGURE 5.

Relaxation data for MTIP, MTIP S108E, and their complexes with the MyoA tail. Shown is variation of backbone 15N T1 and T2 relaxation times and 1H,15N heteronuclear NOEs for wild type MTIP bound to PfMyoA-(799–818) and in the free state (left) and (right) followed by data for MTIP S108E. Below each relaxation dataset, schematic models represent the effect of amino acid substitutions and ligand binding on the orientation of MTIP domains. The average values of T1/T2 are given for each system; these are reported as the mean ± S.D., removing values for residues where T2 < 50 ms or NOE < 0.6. These residues were judged to be undergoing motions separate from the overall tumbling of the MTIP molecules.

Different regions of free MTIP display a variety of dynamic properties. Drops in NOEs from average values indicate that the N- and C-terminal portions are free to move on timescales faster than the tumbling of the rest of the molecule, as are amides in the linker between the domains (Val-135–Asn-140) and residues Gly-172, Ala-174, and Leu-175 in a key MyoA binding loop. The backbone amide resonances of Ile-133–His136, where the N-terminal domain joins the linker, have substantially reduced 15N T2 values, suggesting that the protein exchanges between conformers via the linker on a slower (ms to μs) timescale. Residues Leu-168 and Thr-169 are likewise affected and can be found next to the loop containing Asp-173, which forms the intra-MTIP H-bond to Ser-108 to complete the MyoA binding groove. As mentioned above, the Ser-108 amide itself could not be identified in the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum, and it is likely that this is due to exchange broadening, as adjacent Ser-107 has a shortened T2 (57.2 ms relative to an average of 78.7 ms). The C-terminal 20 residues also show faster T2 relaxation, suggesting conformational flexibility on a slow (ms to μs) timescale.

To investigate these slow dynamics of free MTIP in detail, we used 15N CPMG relaxation dispersion NMR experiments (41) that allowed us to probe exchange processes with low-population conformers (42). To fit our trajectories of R2eff plotted against CPMG frequency, we used the program NESSY (43), enabling us to find the appropriate exchange model on a per-residue basis. Using datasets from two static field strengths (14.1 and 18.8 T), we tested different models for two-site exchange and found that a substantial proportion of amides with observable resonances were subject to exchange processes, with others potentially undetected due to excessive line broadening (Fig. 4). A few residues in the unstructured part of the N terminus, which were shown in the heteronuclear NOE experiment to be flexible on the ns to ps timescale display insignificant ms dynamics; other instances of low Rex observed in isolated parts of MTIP could be a result of the backbone amides in exchanging conformers having very similar 15N chemical shifts. The largest values of Rex were found in the C-terminal domain, but there is also clear evidence of ms timescale dynamics throughout the N-terminal domain, consistent with a model in which both domains move to clamp around the MyoA tail. The linker (residues Val-135–Asn-140), about which the motion is thought to occur, was shown to be dynamic on the fast timescale probed by the heteronuclear NOE experiment, and it appears from these data that it is also dynamic on slower timescales. Very clear relaxation dispersion was observed in the C-terminal helix α8 and the connected short β strand, which appear to be in a different dynamic regime to the rest of the domain; the elevated Rex values may reflect a large chemical shift difference between exchanging conformers and/or a slow rate of exchange (kex). A good fit was obtained using the Carver-Richards model and clustering together the measurable residues of α8, giving an exchange rate kex of 1665 ± 296 s−1 and a minor state population of 2.1%.

In contrast, MTIP bound by MyoA-(799–818) displayed relaxation properties expected of a compact complex with well defined tertiary structure. The exception to this was the N terminus of the protein, where (as in the free state) T2 times rise and NOEs drop considerably from average values due to the presence of ns-ps dynamics. These data suggest that this region is the beginning of the unstructured “N-terminal extension” of MTIP, as it neither appears to contribute to MyoA tail binding nor the folding of the rest of the protein (8, 10). Interestingly, short T2 times were observed in α5, presumably exchange-broadening due to interactions with the N terminus of the peptide as described above. Overall, the relaxation data indicate that the protein loses flexibility in the bound state relative to the free state, in line with observations by ITC that MyoA tail binding is entropically disfavored.

The Phosphomimetic Mutation S108E Causes Major Changes in the Relaxation Properties of the MTIP-MyoA Complex

Having observed a dramatic effect on binding affinity and suggestions that the structure of the complex is altered by the S108E substitution, we sought to investigate whether the dynamics of the protein in solution were also affected (Fig. 5, right). The relaxation properties of the free mutant protein are comparable with those of WT and the main features of the T2, and NOE plots are very similar. One observation is that the average value of the T1/T2 ratio, which can provide an estimate of the system correlation time, is lower in the case of free S108E, suggesting faster tumbling on average. If the Ser-108–Asp-173 interaction occurs transiently in free MTIP as suggested above, it may serve to slow the average tumbling of both domains. Thus, elimination of this interaction by mutation would likely decrease T1 times and increase T2 times and may lead to the effect we observe.

The changes in relaxation properties are much more pronounced when we compare the bound forms of the proteins. In the case of the wild type protein, T1/T2 increases significantly upon ligand binding, presumably due to the addition of the ∼2.5 kDa peptide causing the two domains to tumble as one folded complex. Although in the MTIP S108E complex there is a small increase relative to the free protein, it is not nearly so pronounced, and in fact the T1/T2 average is very close to the value for the wild type MTIP free state. This strongly suggests that the mutant complex has very different tumbling properties compared with the wild type complex and may indicate that parts of the two MTIP domains are free to move independently despite the presence of the MyoA tail. This hypothesis is supported by several observations: (i) the shallower melting transition observed by DSF, suggestive of a less cooperative unfolding process; (ii) that NOEs in the interdomain linker (residues 135–140) in the MTIP S108E-bound state drop significantly, suggesting ns-ps flexibility that is not seen in the wild type MTIP/MyoA complex; (iii) that binding of MyoA-(799–818) to MTIP S108E is much less entropically unfavorable than to MTIP.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated in this study that the native interactions between MTIP and the MyoA tail are better modeled using peptide PfMyoA-(799–818) as a ligand. This peptide binds more tightly than PfMyoA-(803–818), and this result is consistent with additional interactions observed in the new crystal structure of the complex and solution NMR chemical shift perturbation analysis.

Although a number of MTIP phosphorylation events have been reported in vitro, the only residue to be annotated as phosphorylated in P. falciparum parasites is Ser-108. Phosphoproteomic analysis identified tryptic peptides derived from this region of MTIP that are at least monophosphorylated; however, the exact identity of the modified residue remains unclear, as judged by zero calculated confidence in assigning phosphorylation to either Ser-107 or Ser-108 directly from MS/MS spectra (19). As described above, Ser-108 establishes an essential intramolecular interaction with Asp-173 to lock the orientation of domains in the bound form of MTIP. Although this residue is not in direct contact with the ligand, the large decrease in MyoA affinity of the S108E mutant reflects the importance of this position, reinforced by the observation that neighboring S107E has a much smaller but still measurable effect.

The results described here suggest that phosphorylation at Ser-107 and/or Ser-108 in vivo would likely have a significant impact on MyoA motor function as its localization at the inner membrane complex depends on tight interaction with its light chain MTIP, with the effect of modification at the latter residue predicted to be more pronounced. In addition to the substantially weakened affinity of MTIP S108E for the MyoA tail peptide as well as the native myosin, we have shown by unfolding analysis that the structure of the complex is significantly perturbed. NMR experiments have reinforced this in per-residue detail by showing that the mutant MTIP does not form a rigid clamp around its ligand; indeed, some of the dynamics of the free state (for instance, flexibility in the interdomain linker) are maintained in the MTIP S108E-bound state. Furthermore, the physical interaction of recombinant MTIP (wild type and the phosphomimetic S107E and S108E mutants) with P. falciparum lysates confirms the relevance of these interactions in the context of native, full-length MyoA. Importantly, the Ser to Glu substitution represents an approximation to the effect of phosphorylation, meaning that the double negative charge of a phosphate group could amplify the effects we have observed at each position. Because modification at the equivalent positions of T. gondii MTIP (called MLC1) has also been detected (19), it is plausible that this is a conserved feature among Apicomplexa parasites that depends on MyoA motility for gliding and cell invasion. Apart from these residues, other reported in vitro targets for phosphorylation in PfMTIP are Ser-85/Ser-86 (14), located in the border between helix α1 and the α1-α2 loop (at the distal end of the NT domain), and Ser-47/Ser-51 in the disordered N-terminal extension (16). Modification of these positions is less likely to affect complex formation with MyoA, as they are surface-exposed and face away from the binding site. Additional cell-based assays are required to examine the effect of these phosphorylation events in the regulation of P. falciparum motor complex assembly/disassembly and/or activity.

Our extensive analysis of the NMR relaxation properties of free MTIP in solution provide novel, residue-level insight into its dynamics on different timescales that are likely key in MyoA recognition and thus motor complex assembly. We show that many of these dynamic processes are quenched upon ligand binding due to formation of a compact, well folded complex; this is reflected in thermal stability analysis, and observations that clamping of the MyoA tail by MTIP is enthalpically driven and highly disfavored entropically. These results highlight an opportunity to enhance affinity by constraining the observed α-helix conformation of the MyoA tail, for example by applying stapling strategies (44), or by exploiting fragment-based approaches toward α-helix mimetics (45). With this in mind together with our detailed mapping of interaction hotspots and the dynamics of the system in solution, work is on-going in our laboratory to develop novel inhibitors of the P. falciparum MTIP-MyoA complex using structure-guided strategies. Because milligram quantities of isotopically enriched MTIP can be readily produced, the NMR assignments reported here will enable rapid binding site determination for hit compounds and as such provide complementary information to the fluorescence-based inhibition assays that we have recently reported (8).

Acknowledgments

We thank Munira Grainger for the preparation of P. falciparum schizonts used in our binding experiments. We also acknowledge Steve J. Matthews, members of the Cota, Tate, and Matthews laboratories and Dr. Jeremy Moore (Centre for Structural Biology) at Imperial College London for generous support.

This work was supported by Royal Society Grant 2008/R1 (to E. W. T. and E. C.) and UK Medical Research Council Grant U117532067 (to A. A. H.).

This article contains supplemental Table 1 and Figs. 1–4.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4AOM) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- MyoA

- myosin A

- MTIP

- MyoA tail domain interacting protein

- GAP45

- 45-kDa glideosome-associated protein

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- DSF

- differential scanning fluorimetry

- CPMG

- Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- TCEP

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- T

- tesla

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baum J., Papenfuss A. T., Baum B., Speed T. P., Cowman A. F. (2006) Regulation of apicomplexan actin-based motility. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farrow R. E., Green J., Katsimitsoulia Z., Taylor W. R., Holder A. A., Molloy J. E. (2011) The mechanism of erythrocyte invasion by the malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 22, 953–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frénal K., Soldati-Favre D. (2009) Role of the parasite and host cytoskeleton in apicomplexa parasitism. Cell Host Microbe 5, 602–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kappe S. H., Buscaglia C. A., Bergman L. W., Coppens I., Nussenzweig V. (2004) Apicomplexan gliding motility and host cell invasion. Overhauling the motor model. Trends Parasitol. 20, 13–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bergman L. W., Kaiser K., Fujioka H., Coppens I., Daly T. M., Fox S., Matuschewski K., Nussenzweig V., Kappe S. H. (2003) Myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP) localizes to the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium sporozoites. J. Cell Sci. 116, 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Green J. L., Martin S. R., Fielden J., Ksagoni A., Grainger M., Yim Lim B. Y., Molloy J. E., Holder A. A. (2006) The MTIP-myosin A complex in blood stage malaria parasites. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 933–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rees-Channer R. R., Martin S. R., Green J. L., Bowyer P. W., Grainger M., Molloy J. E., Holder A. A. (2006) Dual acylation of the 45-kDa gliding-associated protein (GAP45) in Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 149, 113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas J. C., Green J. L., Howson R. I., Simpson P., Moss D. K., Martin S. R., Holder A. A., Cota E., Tate E. W. (2010) Interaction and dynamics of the Plasmodium falciparum MTIP-MyoA complex, a key component of the invasion motor in the malaria parasite. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 494–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bosch J., Turley S., Roach C. M., Daly T. M., Bergman L. W., Hol W. G. (2007) The closed MTIP-myosin A-tail complex from the malaria parasite invasion machinery. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bosch J., Turley S., Daly T. M., Bogh S. M., Villasmil M. L., Roach C., Zhou N., Morrisey J. M., Vaidya A. B., Bergman L. W., Hol W. G. (2006) Structure of the MTIP-MyoA complex, a key component of the malaria parasite invasion motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4852–4857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delmotte A., Tate E. W., Yaliraki S. N., Barahona M. (2011) Protein multi-scale organization through graph partitioning and robustness analysis. Application to the myosin-myosin light chain interaction. Phys. Biol. 8, 055010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agop-Nersesian C., Egarter S., Langsley G., Foth B. J., Ferguson D. J., Meissner M. (2010) Biogenesis of the inner membrane complex is dependent on vesicular transport by the alveolate-specific GTPase Rab11B. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kortagere S., Welsh W. J., Morrisey J. M., Daly T., Ejigiri I., Sinnis P., Vaidya A. B., Bergman L. W. (2010) Structure-based design of novel small-molecule inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 840–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kato N., Sakata T., Breton G., Le Roch K. G., Nagle A., Andersen C., Bursulaya B., Henson K., Johnson J., Kumar K. A., Marr F., Mason D., McNamara C., Plouffe D., Ramachandran V., Spooner M., Tuntland T., Zhou Y., Peters E. C., Chatterjee A., Schultz P. G., Ward G. E., Gray N., Harper J., Winzeler E. A. (2008) Gene expression signatures and small-molecule compounds link a protein kinase to Plasmodium falciparum motility. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 347–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siden-Kiamos I., Ecker A., Nybäck S., Louis C., Sinden R. E., Billker O. (2006) Plasmodium berghei calcium-dependent protein kinase 3 is required for ookinete gliding motility and mosquito midgut invasion. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 1355–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Green J. L., Rees-Channer R. R., Howell S. A., Martin S. R., Knuepfer E., Taylor H. M., Grainger M., Holder A. A. (2008) The motor complex of Plasmodium falciparum. Phosphorylation by a calcium-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30980–30989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vaid A., Thomas D. C., Sharma P. (2008) Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-PfPKB signaling pathway in erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5589–5597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nebl T., Prieto J. H., Kapp E., Smith B. J., Williams M. J., Yates J. R., 3rd, Cowman A. F., Tonkin C. J. (2011) Quantitative in vivo analyses reveal calcium-dependent phosphorylation sites and identifies a novel component of the Toxoplasma invasion motor complex. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Treeck M., Sanders J. L., Elias J. E., Boothroyd J. C. (2011) The phosphoproteomes of Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii reveal unusual adaptations within and beyond the parasites' boundaries. Cell Host Microbe 10, 410–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lasonder E., Treeck M., Alam M., Tobin A. B. (2012) Insights into the Plasmodium falciparum schizont phospho-proteome. Microbes Infect. 14, 811–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solyakov L., Halbert J., Alam M. M., Semblat J. P., Dorin-Semblat D., Reininger L., Bottrill A. R., Mistry S., Abdi A., Fennell C., Holland Z., Demarta C., Bouza Y., Sicard A., Nivez M. P., Eschenlauer S., Lama T., Thomas D. C., Sharma P., Agarwal S., Kern S., Pradel G., Graciotti M., Tobin A. B., Doerig C. (2011) Global kinomic and phospho-proteomic analyses of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 2, 565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niesen F. H., Berglund H., Vedadi M. (2007) The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2212–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walliker D., Quakyi I. A., Wellems T. E., McCutchan T. F., Szarfman A., London W. T., Corcoran L. M., Burkot T. R., Carter R. (1987) Genetic analysis of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science 236, 1661–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lambros C., Vanderberg J. P. (1979) Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J. Parasitol. 65, 418–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor H. M., Grainger M., Holder A. A. (2002) Variation in the expression of a Plasmodium falciparum protein family implicated in erythrocyte invasion. Infect. Immun. 70, 5779–5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leslie A. G. W., Powell H. R. (2007) in Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography (Read R., Sussman J. L., eds) pp. 41–51, Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX. A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe. A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson B. A. (2004) Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol. Biol. 278, 313–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jung Y. S., Zweckstetter M. (2004) Backbone assignment of proteins with known structure using residual dipolar couplings. J. Biomol. NMR 30, 25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marchant J., Sawmynaden K., Saouros S., Simpson P., Matthews S. (2008) Complete resonance assignment of the first and second apple domains of MIC4 from Toxoplasma gondii using a new NMRView-based assignment aid. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2, 119–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mulder F. A., Skrynnikov N. R., Hon B., Dahlquist F. W., Kay L. E. (2001) Measurement of slow (micros-ms) time scale dynamics in protein side chains by 15N relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. Application to Asn and Gln residues in a cavity mutant of T4 lysozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 967–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luz Z., Meiboom S. (1963) Nuclear magnetic resonance study of proteolysis of trimethylammonium ion in aqueous solution. Order of reaction with respect to solvent. J. Chem. Phys. 39, 366–370 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carver J. P., Richards R. E. (1972) A general two-site solution for the chemical exchange produced dependence of T2 upon the carr-Purcell pulse separation. J. Magn. Reson. 6, 89–105 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. (1994) The 13C chemical-shift index. A simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Masino L., Martin S. R., Bayley P. M. (2000) Ligand binding and thermodynamic stability of a multidomain protein, calmodulin. Protein Sci. 9, 1519–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palmer A. G., 3rd, Kroenke C. D., Loria J. P. (2001) Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for quantifying microsecond-to-millisecond motions in biological macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 339, 204–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baldwin A. J., Kay L. E. (2009) NMR spectroscopy brings invisible protein states into focus. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 808–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bieri M., Gooley P. R. (2011) Automated NMR relaxation dispersion data analysis using NESSY. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Verdine G. L., Hilinski G. J. (2012) Stapled peptides for intracellular drug targets. Methods Enzymol. 503, 3–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oltersdorf T., Elmore S. W., Shoemaker A. R., Armstrong R. C., Augeri D. J., Belli B. A., Bruncko M., Deckwerth T. L., Dinges J., Hajduk P. J., Joseph M. K., Kitada S., Korsmeyer S. J., Kunzer A. R., Letai A., Li C., Mitten M. J., Nettesheim D. G., Ng S., Nimmer P. M., O'Connor J. M., Oleksijew A., Petros A. M., Reed J. C., Shen W., Tahir S. K., Thompson C. B., Tomaselli K. J., Wang B., Wendt M. D., Zhang H., Fesik S. W., Rosenberg S. H. (2005) An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumors. Nature 435, 677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]