Background: Cytochrome c oxidase reduces O2 to H2O, a reaction coupled to proton translocation across the membrane.

Results: Photolysis of CO from the mixed valence form of cytochrome ba3-CO does not lead to a heme a33+-CuB1+-CO binuclear center.

Conclusion: The absence of reverse electron transfer between hemes a3 and b is shown.

Significance: Unique thermodynamic and kinetic properties of cytochrome ba3 oxidase are presented.

Keywords: Bioenergetics/Electron Transfer Complex, Cytochrome Oxidase, Enzyme Catalysis, Enzyme Kinetics, Fourier Transform IR (FTIR), Multifunctional Enzymes, Spectroscopy

Abstract

The complete understanding of a molecular mechanism of action requires the thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of different states and intermediates. Cytochrome c oxidase reduces O2 to H2O, a reaction coupled to proton translocation across the membrane. Therefore, it is necessary to undertake a thorough characterization of the reduced form of the enzyme and the determination of the electron transfer processes and pathways between the redox-active centers. In this study Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and time-resolved step-scan FTIR spectroscopy have been applied to study the fully reduced and mixed valence states of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. We used as probe carbon monoxide (CO) to characterize both thermodynamically and kinetically the cytochrome ba3-CO complex in the 5.25–10.10 pH/pD range and to study the reverse intramolecular electron transfer initiated by the photolysis of CO in the two-electron reduced form. The time-resolved step-scan FTIR data revealed no pH/pD dependence in both the decay of the transient CuB1+-CO complex and rebinding to heme a3 rates, suggesting that no structural change takes place in the vicinity of the binuclear center. Surprisingly, photodissociation of CO from the mixed valence form of the enzyme does not lead to reverse electron transfer from the reduced heme a3 to the oxidized low-spin heme b, as observed in all the other aa3 and bo3 oxidases previously examined. The heme b-heme a3 electron transfer is guaranteed, and therefore, there is no need for structural rearrangements and complex synchronized cooperativities. Comparison among the available structures of ba3- and aa3-cytochrome c oxidases identifies possible active pathways involved in the electron transfer processes and key structural elements that contribute to the different behavior observed in cytochrome ba3.

Introduction

Most biochemical redox reactions involve intramolecular delivery of electrons through a donor-acceptor pair (1–5). Determination of the pathways and dynamics of electron transfer (ET)2 is of crucial importance for understanding many catalytic reactions, especially when the redox-linked changes are coupled to other processes such as proton transfer and protonation/deprotonation events. Because both the electron transfer pathways and the conformational changes that lead to proton translocation are controlled by the protein structure, identification of both electron transport chains and proton labile residues is a necessary step toward the elucidation of the overall mechanism of function.

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is the terminal membrane protein of cellular respiration in most aerobic organisms (6, 7). It catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen to water using electrons from cytochrome c in a process coupled with the pumping of protons across the membrane. The internal electron flow through the four redox centers (Scheme 1) (8–12) and the accompanied proton uptake to form H2O is energetically and mechanistically linked to proton translocation generating the gradient that drives the synthesis of ATP. However, the mechanism of this linkage and the protein residue cofactors involved in the electron/proton transfer pathways remain unclear.

The ba3-type cytochrome c oxidase from the extremely thermophilic eubacterium Thermus thermophilus HB8 is expressed under elevated temperatures (47–85 °C) and limited oxygen supply (13, 14). As a bacterial terminal respiratory protein complex, it is located in the plasma membrane and catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen to water, a process coupled to proton translocation from the cytoplasm to the periplasm. Furthermore, cytochrome ba3 and its counterpart cytochrome caa3 are capable of reducing NO to N2O, although with a low activity (15–19). Despite the very low (<20%) overall sequence homology to other structurally known cytochrome c oxidases, the four redox centers of cytochrome ba3 display high similarity with those of other oxidases (20–23). The mixed valence (CuA1.5+-CuA1.5+) complex, bridged by Cys-149 and Cys-153 and coordinated by His-114, His-157, Met-160, and Gln-151 is located 19.0 Å away from the low-spin heme b, which is ligated by His-72 and His-386. The low-spin heme is connected to the high-spin heme a3 of the binuclear center through His-386, Phe-385, and axially coordinated to heme a3 His-384. The Fe3+-to-Fe3+ distance between the two hemes is 13.9 Å; however, they approach each other at a short edge-to-edge distance of 5.0 Å and an angle of 110°. The CuB2+ atom of the binuclear center is located 4.4 Å from heme a3 Fe3+ and is coordinated by His-233, His-282, and His-283. In the reduced form of the enzyme this distance appears enlarged by 0.3 Å (23). The only unusual features in cytochrome ba3 oxidase, compared with the other heme-copper oxidases, are the relatively short heme a3 Fe3+-CuB2+ distance at 4.4 Å (20), (4.8–5.3 Å in aa3-, bo3-, and cbb3-type oxidases) and the significantly larger heme a3 Fe3+-His-384 distance at 3.3 Å (2.0–2.2 Å in aa3-, bo3- and cbb3-type oxidases) (24–32).

Three distinct families of heme-copper oxidases have been identified. The type A oxidase superfamily is similar to the mitochondrial (aa3) enzyme. The type-B oxidase is related to the ba3 from T. thermophilus whereas the type C are the cbb3 type oxidases. The thermophilic Gram-negative eubacterium T. thermophilus HB8 (ATCC27634) expresses cytochromes caa3 and ba3, which serve as terminal oxidases for reducing oxygen to water. In contrast to the environment of the four metal centers, several amino acid residues that have been shown to be essential for proton transfer in other cytochrome c oxidases are not conserved in cytochrome ba3 oxidase (20, 21). Specifically, most of the amino acids forming the K and D channels, established for the mitochondrial enzymes, are replaced, and only the modified K-channel shows a possible functionality (20, 33). On this line, the axial heme a3 ligand His-384 as well as Asn-366, Asp-372, and the propionate group of heme a3 pyrrole ring A (20, 34, 35), leading to the conserved among all structurally known oxidases, water pool, which is connected to the bulk solvent, has been proposed to serve as the primary acceptor of both the pumped protons and the catalytically formed water molecules. Besides the significant structural differences observed in the proton pathways, a vectorial consumption of 1.0 H+/e− was measured for the water formation along with a lowered proton pumping efficiency of 0.5 H+/e− instead of 1.0 H+/e− found in other oxidases (36, 37).

Several techniques have been employed to study the intraprotein electron transfer reactions during the enzyme catalysis, but it proved difficult to directly monitor the sequence of these non-light driven processes (38–43). However, the final heme-heme electron transfer step can be followed through the reverse electron flow between the two hemes, initiated by photolysis of CO from the reduced heme a3 or b3/o3 under conditions where the low-spin heme a or b is initially oxidized. This form of the enzyme can be prepared by overnight exposure of the protein solution to CO gas and through the oxidation of CO to CO2, leading to the so-called mixed valence state where the binuclear center is reduced but the other two electron donor sites (low-spin heme and CuA) remain oxidized (44). Binding of CO to heme a3 raises the redox potential of the high-spin heme and traps the electrons at the active site. Photodissociation of CO from the high-spin heme causes the lowering of the heme redox midpoint potential and reverse electron transfer among the redox centers. Studies on aa3 oxidases showed that fast electron equilibration between the two hemes occurs on the nanosecond time scale followed by additional redistribution with time constant of few μs (45, 46). At later times (30–50 μs) further equilibration involves the CuA complex; however, its extent is small. At high pH values the overall process includes an additional ET phase between the hemes, in the millisecond time range, which is coupled to proton transfer through the K-pathway and release of a proton to the bulk medium. Rebinding of CO to high-spin heme induces the back-reactions of electron and proton transfer. This way the reverse ET in various CcOs was determined and found to be from 25 to 35% in Escherichia coli bo3 (47) and bovine heart aa3 (48) to 50–100% in Paracoccus denitrificans and Rhodobacter sphaeroides aa3 oxidases (49–52).

In the case of fully reduced cytochrome ba3, the heme a3-CuB binuclear center is subjected to peculiar properties (53–57) characterized by a high affinity of CuB for CO (K > 104 m−1) and a slow intramolecular ligand transfer to heme a3 (k = 8 s−1). As a result, cytochrome ba3 is the only documented oxidase where the binding of CO to CuB is exergonic and accounts for 25–30% of the total enzyme concentration (34). Time-resolved step-scan FTIR studies showed that after photolysis of CO from heme a32+, the ligand is almost quantitatively transferred to CuB1+, and the transiently formed CuB1+-CO complex exhibits an unusual long lifetime of 20 ms. The midpoint redox potentials of hemes b and a3 have been reported by two groups and found them inverted, having values of 210/213 and 430/285 mV (versus Normal Hydrogen Electrode), respectively (58, 59). It was concluded that uncommon electron transfer properties should be expected relative to other oxidases. However, there is no experimental evidence about the active ET pathways that contribute to them and how the observed kinetic and thermodynamic deviations, relative to the mesophilic aa3-type oxidases, are linked to protein structure.

This study focuses on two main subjects. The first is to fully characterize the reduced form of the enzyme through the binding of CO in a wide pH/pD range and follow the transient events occurred after the CO-photolysis from heme a3. This way we will reach definite thermodynamic and kinetic conclusions about structural changes that may play a role under physiologically relevant conditions. A time-resolved step-scan FTIR technique is a sensitive probe able to monitor these transient and/or labile structures. The second is to use FTIR spectroscopy to follow the possible intramolecular electron transfer between the redox-active centers in ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from T. thermophilus.

The property of selectively reducing the heme a3-CuB binuclear site by the inhibitor CO permits the measurement of the rate constants of the individual ET reactions through the extent of the reverse electron transfer induced by the photodissociation of CO from heme a3 Fe2+. Surprisingly, photolysis of CO from heme a3 does not result in reverse electron transfer from the heme a3 to the low spin heme b, as it has been observed in all other heme-copper oxidases previously examined. Furthermore, comparison between the equilibrium fully-reduced and -mixed valence spectra suggests that the proposed CuA-CuB direct electron transfer pathway is not active in the reverse (back) direction. These results together with the already known inverted midpoint potentials of hemes b and a3 suggest that cytochrome ba3 uses a different mechanism of energy conversion to achieve exergonicity during catalysis. Tracing the observed and calculated ET pathways found in other oxidases, in the cytochrome ba3 structure, allows us to identify the key structural differences that lead to this unusual behavior. Because the direct (redox-driven) or indirect (through conformational changes) coupling of the electron transfer/oxygen chemistry and proton pumping activity is generally accepted, the study presented here provides evidences for the overall mechanism of action. Finally, we discuss the conclusions in terms of how the proteins from thermophilic microorganisms are adapted to their extreme environment and what structural changes they use relative to the mesophilic ones to function effectively.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sample Preparation

Cytochrome ba3 was isolated from T. thermophilus HB8 cells according to previously published procedures (20). The samples used for the FTIR measurements had an enzyme concentration of 1.0–1.5 mm and were placed in a desired buffer (pH/pD 5.25–6.50, MES; pH/pD 6.50–8.50, Tris or HEPES; pH/pD 8.50–10.10, CHES). The solutions prepared in D2O were measured assuming pD = pH + 0.4 (60). The fully reduced [(CuA-CuA)2+, Feb2+, Fea32+, CuB1+] ba3-CO complexes were formed by the exposure of sodium dithionite-reduced samples to 1 atm of CO (0.93 mm) and transferred to a tightly sealed FTIR cell composed of two CaF2 windows under anaerobic conditions. The path length was 14 and 21 μm for the H2O and D2O solutions, respectively. 12CO (99.5%) gas was obtained from Messer (Germany), and isotopic CO (13CO) was purchased from Isotec (Miamisburg, OH). The mixed valence [(CuA-CuA)3+, Feb3+, Fea32+, CuB1+] CO-bound form of the enzyme was prepared by overnight incubation of oxidized cytochrome ba3 with CO in the complete absence of O2 at room temperature. Upon oxidizing CO to CO2 (CO + H2O → CO2 + H2) the enzyme becomes partially reduced and is stabilized by the binding of CO (44). To obtain the high concentration of the mixed valence ba3-CO complex required for the FTIR measurements, a small amount of sodium dithionite Na2S2O4 (250 μm) was introduced in the ba3 sample to initiate the process. Under these conditions no significant trace of fully reduced cytochrome ba3 was detected as verified from the optical spectrum.

FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR measurements were performed on a Bruker Equinox IFS55 spectrometer equipped with an mercury cadmium telluride detector (Graseby D316). Its preamplifier (ac-coupled) allows us to record spectra with signal-to-noise ratios higher than 40.000/1 in 1000 scans. All the spectra presented here are an average of 2000 scans. The instrument and the optical pathway were purged with N2, the spectral resolution was 4 cm−1, and the covered spectral range was 1200–3000 cm−1. Power spectrum apodization with 32 cm−1 phase resolution and 4-point phase correction algorithm were used. The temperature was 20 °C. The 416-nm line of a continuous wave TuiOptics Diode Laser System (DL 100) was used as a pump light to photodissociate CO from cytochrome ba3-CO complex. The incident power on the sample was 13 milliwatts, which corresponds to a photolysis yield of 35%. Care was taken with the mixed valence samples because prolonged irradiation leads to photoreduction to the fully reduced cytochrome ba3-CO. All the spectra shown are static light (laser-irradiated protein)-minus-dark (no irradiation) difference spectra reflecting the CO-dissociated form (positive peaks) and the CO-bound enzyme (negative peaks). The optical absorption spectra were recorded with a PerkinElmer Life Sciences Lambda 20 UV/visible spectrometer.

Time-resolved Step-scan FTIR Spectroscopy

The 532-nm pulses from a continuum Nd-YAG laser (7-ns wide, 3–7 Hz) were used as a pump light (10 mJ/pulse) to photolyse the ba3-CO oxidase. FTIR measurements were performed on a Bruker Equinox IFS 55 spectrometer equipped with the step-scan option (Bruker, Newark, DE). For the time-resolved experiments, a TTL pulse (transistor transistor logic) provided by a digital delay pulse generator (Quantum Composers, 9314T) triggers, in order, the flashlamps, Q-switch, and the FTIR spectrometer. Pretriggering the FTIR spectrometer to start data collection before the laser fires allows 11 fixed reference points to be collected at each mirror position, which are used as the reference spectrum in the calculation of the difference spectra. Changes in intensity were recorded with an mercury cadmium telluride detector (Graseby infrared D316, response limit 600 cm−1) amplified in the dc-coupled mode and digitized with a 200-kHz, 16-bit, analog-to-digital converter. A broadband interference optical filter (Optical Coating Laboratory, Santa Rosa, CA) with short wavelength cut-off at 2.67 μm was used to limit the free spectral range from 2.67 to 8 μm. This leads to a spectral range of 3900 cm−1, which is equal to an under-sampling ratio of 4. Single-sided spectra were collected at 8 cm−1 spectral resolution, 5- or 100-μs time resolution, and 10 co-additions per data point. Total accumulation time for each measurement was 60 min, and 2–3 measurements were collected and averaged. Blackman-Harris three-term apodization with 32 cm−1 phase resolution and the Mertz phase correction algorithm were used. Difference spectra were calculated as ΔA = −log(IS/IR).

RESULTS

CO Binding in the Fully Reduced and Mixed Valence States of Cytochrome ba3

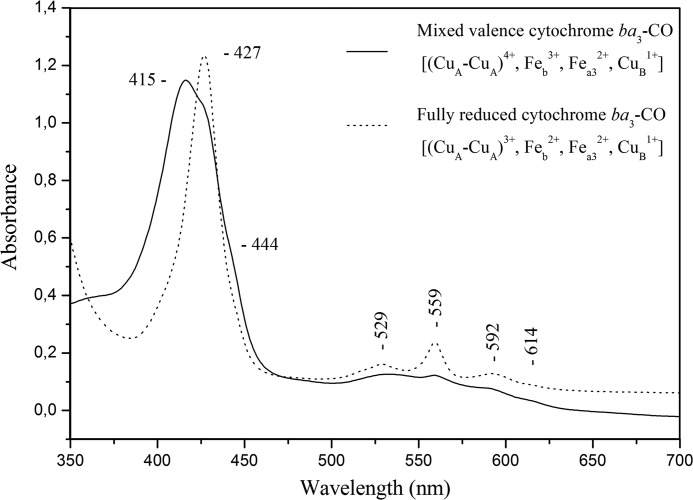

Fig. 1 displays the optical absorption spectra of the fully reduced [(CuA-CuA)2+, Feb2+, Fea32+, CuB1+] and mixed valence [(CuA-CuA)3+, Feb3+, Fea32+, CuB1+] ba3-CO complexes. The addition of CO to dithionite-reduced enzyme causes a shift of the Soret band of heme a32+ from 444 to 427 nm and of the visible band from 614 to 592 nm, whereas the bands of the reduced heme b at 427 and 559 nm remain unchanged (34). Overnight incubation of oxidized cytochrome ba3 with CO results to the reduction of the binuclear center, whereas the heme b and CuA centers remain oxidized. This form of the enzyme is finally stabilized by the binding of CO to heme a3 Fe2+ and CuB1+. The optical spectrum shown in Fig. 1 confirms the mixed valence state of the ba3-CO complex as it exhibits band characteristics of the heme a32+-CO complex at 427 and 592 nm, of oxidized heme b at 415 nm, and of reduced heme a3 at 444 and 614 nm. The fraction of the unligated heme a32+ represents the equilibrium complex A (Scheme 2) (34), where the CO is bound to CuB and is calculated to the same extent as in the fully reduced state of the enzyme (25%). Based on the small 559-nm band that appeared in the spectrum of the mixed valence cytochrome ba3-CO, we also conclude that 5–8% of heme b is reduced.

FIGURE 1.

Optical absorption spectra of cytochrome ba3-CO complex at pH 8.5. The solid line represents the MV form [(CuA-CuA)3+, Feb3+, Fea32+, CuB1+], and the dotted line represents the FR form [(CuA-CuA)2+, Feb2+, Fea32+, CuB1+)] of the ba3-CO complex.

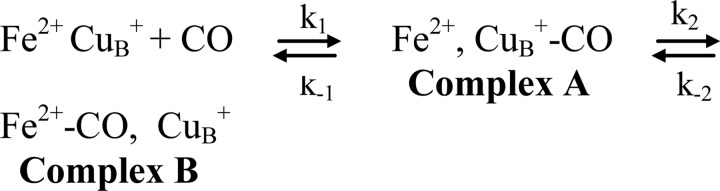

SCHEME 2.

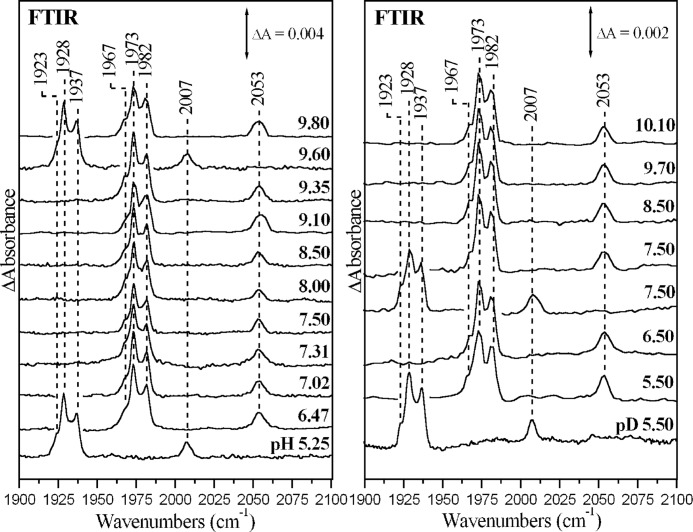

Fig. 2 presents the equilibrium FTIR spectra of the fully reduced cytochrome ba3-12CO complex at the indicated pH and pD values. The spectra at pH 5.25 and 9.60 and pD 5.50 and 7.50 represent the ba3-13CO complex. In the 12C16O derivatives we observes four CO-sensitive modes at 1967, 1973, 1982, and 2053 cm−1, which shift to 1923, 1928, 1937, and 2007 cm−1, respectively, upon replacement of 12CO with 13CO. The first three peaks are assigned to the C-O stretching vibration of heme a3 Fe2+-CO complex (equilibrium complex B, Scheme 2), whereas the peak at 2053 cm−1 represents the equilibrium CuB1+-CO complex (equilibrium complex A, Scheme 2), which accounts for almost 25% of the enzyme (34). The frequencies and bandwidths of these C-O modes remained unchanged between H2O and D2O and also in the 5.25–10.10 pH/pD range.

FIGURE 2.

Absolute FTIR spectra of cytochrome ba3-CO. Shown are FTIR spectra of the fully reduced cytochrome ba3-CO complex at indicated pH and pD values. The spectra at pH 5.25 and 9.60 and pD 5.50 and 7.50 represent the ba3-13CO complex. Enzyme concentration was 1.0 mm, the path length was 15–25 μm, and the spectral resolution was 2–4 cm−1. The total number of scans was 1000.

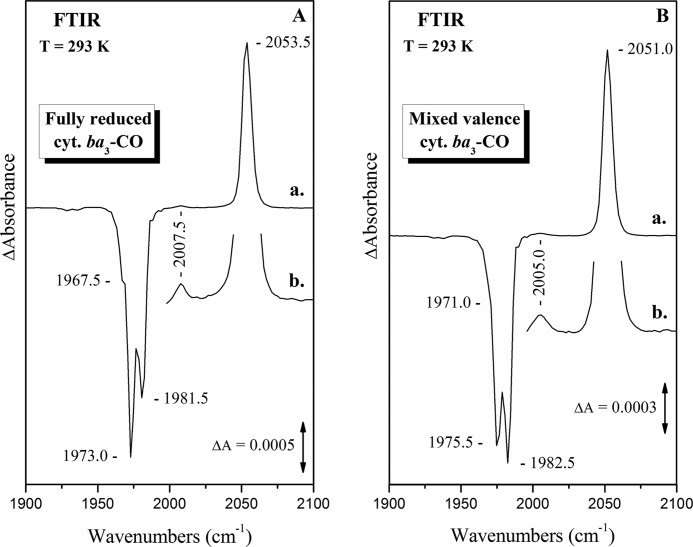

Fig. 3A shows the double difference equilibrium FTIR spectrum of the fully reduced (FR) cytochrome ba3-CO complex at pD 8.5. Three major heme a3 Fe2+-CO conformers are evident from the presence of CO-sensitive modes at 1967.5, 1973.0, and 1981.5 cm−1, whereas the CuB1+-CO complex (2053.5 cm−1) adopts a single conformation. The ratio of the Fe-CO/Cu-CO relative areas is 5.2 and considering the integrated absorptivities expected for the observed heme a32+-CO and CuB1+-CO complexes (ϵFe-CO/ϵCu-CO = 1.68) (61), we conclude that 73% of the enzyme has the CO bound in heme a3 and 27% in the CuB. This ratio corresponds to an equilibrium constant of 2.7, or ΔG° = −0.55 kcal/mol, for the transfer of CO from CuB to heme a3 Fe2+ at 293 K. The three major modes at 1967.5, 1973.0, and 1981.5 cm−1 represent the 93.5% of the total heme a3 Fe2+-CO complexes, and their relative ratios reflect an energy difference ΔG° of −0.15 and −0.70 kcal/mol between the 1981.5–1973.0 cm−1 and 1967.5–1973.0 cm−1 conformers, respectively, at 293 K. None of the observed modes showed sensitivity to H/D exchange and in the 5.25–10.10 pH/pD range, suggesting a highly rigid and hydrophobic environment for the binuclear center (34, 62). The adoption of a single geometry for the CuB1+-CO complex reflects the stability of the CuB environment (His-282, His-283, His-233–Tyr-237), which is not subjected to protonation/deprotonation changes.

FIGURE 3.

Absolute FTIR spectra of cytochrome ba3-CO. A, shown is a FTIR spectrum of the fully reduced [(CuA-CuA)2+, Feb2+, Fea32+, CuB1+] cytochrome ba3-CO complex at pD 8.5. B, shown is a FTIR spectrum of the mixed valence [(CuA-CuA)3+, Feb3+, Fea32+, CuB1+] cytochrome ba3-CO complex at pD 8.5. Enzyme concentration was 1.5 mm, the path length was 56 μm, and the spectral resolution was 4 cm−1. The total number of scans was 2000.

Fig. 3B presents the double difference equilibrium FTIR spectrum of the mixed valence (MV) ba3-CO complex at pD 8.5. All the heme a3 Fe2+-CO modes detected for the FR state are slightly (1–3 cm−1) upshifted, and the CuB-CO mode is downshifted by 2.5 cm−1, in agreement with previous observations for the E. coli bo3 and bovine aa3 oxidases (47, 48, 63). The three major peaks at 1971.0, 1975.5, and 1982.5 cm−1 represent again the 93.0% of the total heme a3 Fe2+-CO complexes; however, the high energy conformer becomes dominant in expense of the 1973.0 cm−1 (FR state) conformer. No difference in the 6.50–8.50 pH/pD range was detected, in agreement with the observations made for the FR state (data not shown). The relative Fe-CO/CuB-CO area ratio is reduced to 4.7 from 5.2 in the FR state; considering the change of the integrated absorptivities for the shifted heme a32+-CO and CuB1+-CO bands (ϵFe-CO/ϵCu-CO = 1.62), we calculate a 71–29% equilibrium ratio of the bound CO between the heme a3 Fe2+ and CuB centers. The observed frequency shifts of the CO-bound modes and the inverted population ratio between the 1973.0 and 1981.5 cm−1 conformers are attributed to the presence of CO2/H2CO3 molecules, catalytically formed during the reduction of the binuclear center by the CO. The altered electrostatic interactions induced by the presence of the CO2/H2CO3 molecules in the binuclear center appears to shift the fragile (0.15 kcal/mol) equilibrium toward the 1981.5 cm−1 conformer. However, these changes do not seem enough to drive the 1967.5–1973.0 cm−1 modes equilibrium (0.70 kcal/mol), and their magnitude is calculated to 0.50 kcal/mol, as evidenced from the slight equilibrium shift in the heme a3 to CuB CO transfer. Details about this effect will be given elsewhere.

Comparison between the spectra presented in Fig. 3 reveals that no extra CO-sensitive modes relative to the FR, is detected in the MV state of cytochrome ba3-CO complex. Through the crystal structure it was proposed that CuB might be involved in a direct electron transfer pathway between the CuA site and the binuclear center. Our data clearly show that CuB remains reduced when CO is bound to heme a3, and no reverse electron transfer takes place between CuB and CuA. If a (CuA-CuA)2+, Fea32+-CO, CuB2+ complex would be generated instead of the ordinary (CuA-CuA)3+, Fea32+-CO, CuB1+, the heme a32+-CO complex would exhibit different C-O stretching frequencies. In particular, the C-O modes would be shifted to lower frequencies, as the more polar CuB2+ would stabilize the Cδ+-Oδ− resonance form. However, these results do not exclude the possibility of the forward ET between the two Cu sites.

Photodissociation of CO from the Fully Reduced and Mixed Valence States of Cytochrome ba3

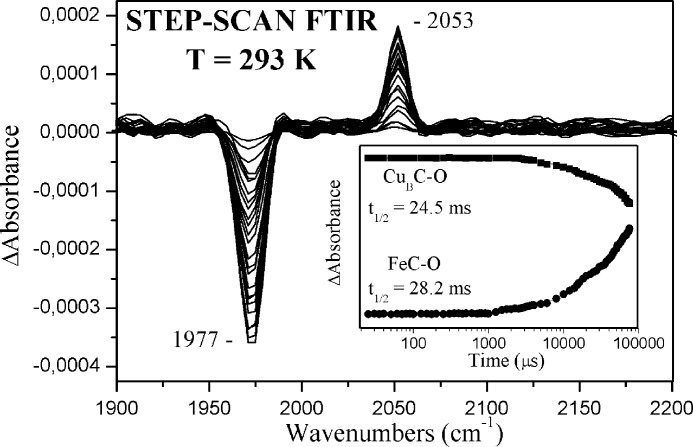

Fig. 4 shows the step-scan time-resolved FTIR difference spectra (td = 150 μs-78.5 ms, 8-cm−1 spectral resolution) of fully reduced ba3-CO (pH 6.50) subsequent to CO photolysis by a nanosecond laser pulse (532 nm). Under these experimental conditions, the 1967, 1973, and 1982 cm−1 peaks cannot be resolved, and thus a single negative peak was observed at 1977 cm−1. The negative peak at 1977 cm−1 arises from the photolysed heme a3-CO. The positive peak that appears at 2053 cm−1 is attributed to the C-O stretch (νCO) of the transiently formed CuB1+-CO complex, as found under continuous light illumination (53), and arises from the near ballistic transfer of the photolysed CO to CuB. Its intensity persists until almost 70 ms. The frequency of the C-O mode in the transient CuB1+-CO complex is the same as that of the equilibrium CuB1+-CO (complex A). This observation suggests that no structural change at CuB occurs in association with CO binding to and dissociation from heme a3. No significant intensity variations are detected in the transient difference spectra (td = 5–3000 μs) for either the 2053 and 1977 cm−1 modes. At later times, however, the decreased intensity of the transient 2053 cm−1 mode (3–70 ms) is accompanied by an increased intensity at 1977 cm−1. The intensity ratio (≈1.5) of the Fe-CO/CuB-CO remains constant for all data points, and thus, we conclude that no significant fraction of CO escapes the binuclear center at 293 K (34). This is consistent with the low temperature experiments in which it was demonstrated that the CuB1+-CO intermediate is fully formed and that no significant fraction of CO escapes the metal centers below 300 K (53).

FIGURE 4.

Time-resolved step-scan FTIR spectra of photodissociated cytochrome ba3-CO. Shown are step-scan time-resolved FTIR difference spectra of the CO-bound form of fully reduced cytochrome ba3 (pH 6.50) at 0.15, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 64, 70, and 78.5 ms subsequent to CO photolysis. The spectral resolution was 8 cm−1, and the time resolution was 100 μs. A 532-nm, 10-mJ/pulse pump beam was used for photolysis.

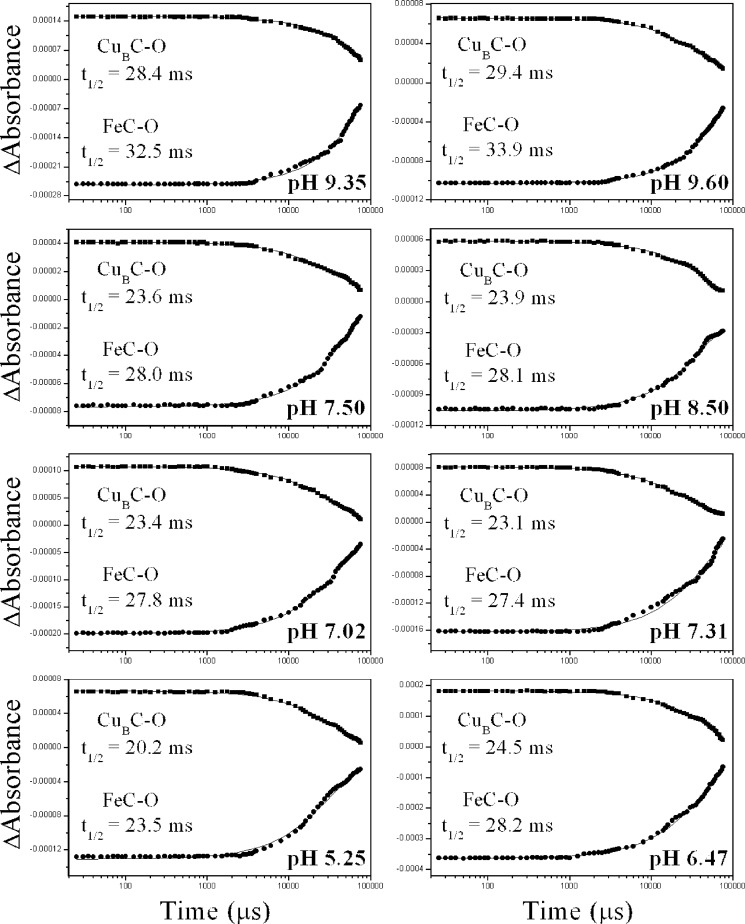

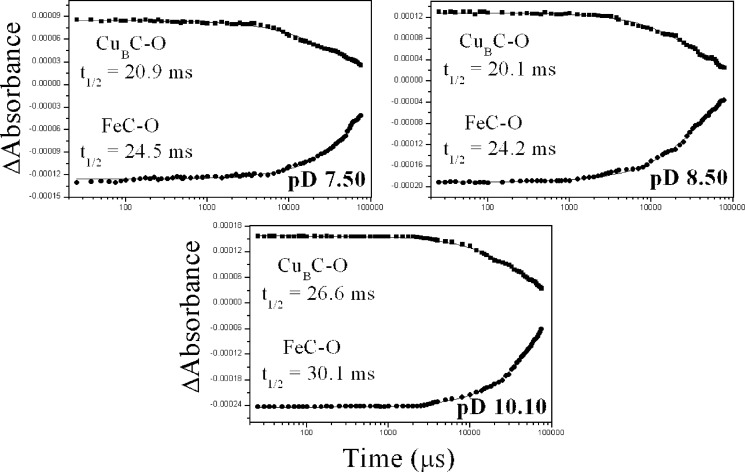

Figs. 5 and 6 display the kinetic evolution of the 1977 (photolysed heme a32+-CO complex) and 2053 cm−1 (transiently formed CuB1+-CO complex) modes at the indicated pH and pD values. The data showed no significant pH dependence of both rates. The rate of the transiently formed CuB1+-CO complex exhibited a decay with t½ = 23.6 ms, which corresponds to a k1obs value of 29.4 s−1 at pH 7.50, and this rate became slightly (≈15%) bigger at pH < 6.00 and smaller (≈20%) at pH > 9.00. Rebinding of CO to heme a3 Fe2+ occurred with t½ = 28.0 ms (k2obs = 24.8 s−1), and this rate was also slightly pH-dependent in the same trend as the decay of the CuB1+-CO complex. The same behavior was observed in the experiments performed in D2O (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 5.

Kinetic analysis of the heme a32+-CO and CuB1+-CO modes at indicated pH values. Shown is a plot of the 2053 cm−1 (squares) and 1977 cm−1 (circles) modes versus time subsequent to CO photolysis. ΔA was measured from the bands area at times between 0 and 78.5 ms subsequent to CO photolysis from heme a3. The curves are three-parameter exponential fits to the experimental data according to first-order kinetics.

FIGURE 6.

Kinetic analysis of the heme a32+-CO and CuB1+-CO modes at indicated pD values. Shown is a Plot of the 2053 cm−1 (squares) and 1977 cm−1 (circles) modes versus time subsequent to CO photolysis. ΔA was measured from the band areas at times between 0 and 78.5 ms subsequent to CO photolysis from heme a3. The curves are three-parameter exponential fits to the experimental data according to first-order kinetics.

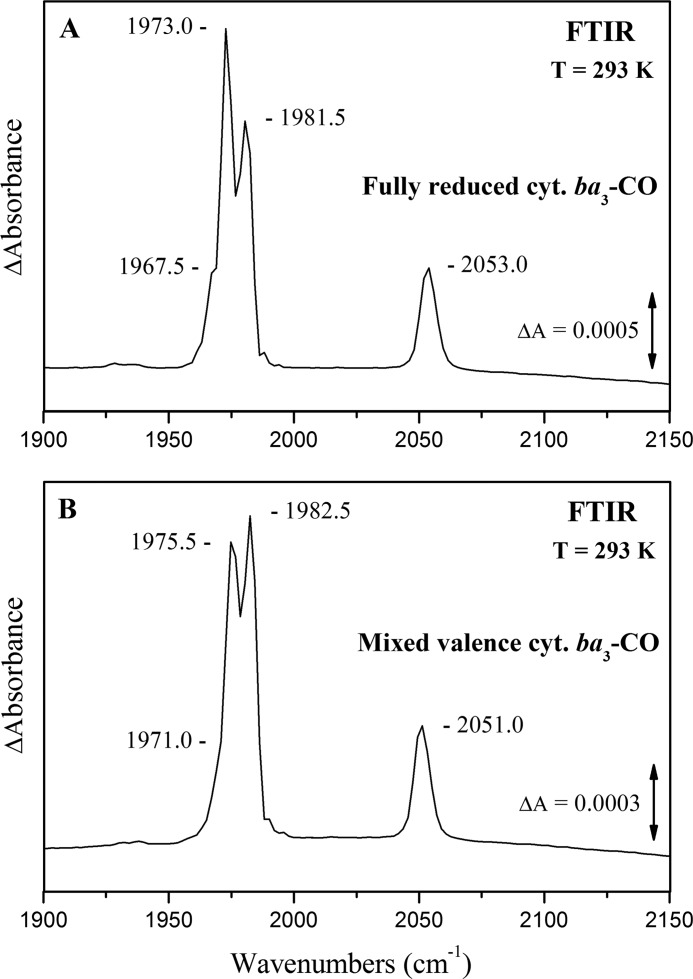

Fig. 7A shows the static light-minus-dark FTIR spectrum of fully reduced ba3-CO complex. Photolysis of the heme a3-CO complex by 416 nm c.w. laser light results in the migration of CO to CuB. The ratios of the negative Fe-CO bands were the same with those observed in the absolute FTIR spectrum, and the frequency of the transient CuB-CO complex was the same (2053.5 cm−1) with that of the equilibrium complex. Besides the small CuB-13CO band at 2007.5 cm−1, which represents the 1.1% natural abundance of 13CO, no other CuB-CO mode was detected in the 2000–2100 cm−1 spectral region (Fig. 7A, spectrum b), even at a ratio of 0.5% of the 2053.5 cm−1 peak. This is in agreement with the absolute FTIR spectrum where only a single CuB-CO mode was detected in contrast to the multiple heme a3 Fe-CO modes. The ratio of the Fe-CO/CuB-CO integrated areas is 2.32. Using Alben's correlation of vibrational frequencies with the integrated absorptivities for CO complexes, we conclude that 75% of the photolysed CO is transferred to CuB. This value is somewhat lower than the 100% reported earlier in the time-resolved step-scan FTIR study of the ba3-CO (34). However, the difference is attributed to the limited spectral resolution (8 cm−1) of the step-scan measurements, under which the absolute intensities of the multiple heme a3-CO bands could not be resolved.

FIGURE 7.

Difference FTIR spectra of photodissociated cytochrome ba3-CO. A, shown is a light-minus-dark difference FTIR spectrum of the CO-bound form of fully reduced cytochrome ba3 oxidase at pD 8.5 (a) and the same spectrum expanded by a factor of 10 in the 2000–2100 cm−1 spectral region (b). The peak at 2007.5 cm−1 corresponds to the 1.1% CuB-13CO complex. B, shown is a light-minus-dark difference FTIR spectrum of the CO-bound form of mixed valence cytochrome ba3 oxidase at pD 8.5 (a) and the same spectrum expanded by a factor of 10 in the 2000–2100 cm−1 spectral region (b). The peak at 2005.0 cm−1 corresponds to the 1.1% CuB-13CO complex. Enzyme concentration was 1.5 mm, the path length was 56 μm, and the spectral resolution was 4 cm−1. The excitation wavelength was 416 nm, and the incident power 13 milliwatts. The photolysis yield is calculated to be 35%.

Fig. 7B displays the light-minus-dark difference FTIR spectrum of mixed valence cytochrome ba3-CO complex subsequent to a 416-nm laser photolysis. In agreement with the FR complex, the transient CuB-CO complex in the MV form absorbed at the same frequency as the equilibrium one at 2051.0 cm−1, and no changes were observed after H2O/D2O exchange and in the 6.5–8.5 pH range (data not shown). However, the ratio of the Fe-CO/CuB-CO integrated areas was reduced to 2.06 compared with the 2.32 value in the FR ba3-CO, leading to an 80% transfer of the photolysed CO to CuB. The increased compared with FR, transfer of CO to CuB is attributed to structural changes in the binuclear center due to the presence of the CO2/H2CO3 molecules, byproducts of the MV ba3-CO complex formation. We suggest that carbon dioxide occupies the same secondary binding site, which has been previous shown to temporally host photolysed CO molecules preventing this way the escape of CO to the solvent (64, 65).

As shown in the 10-fold expanded 2000–2100 cm−1 spectral region (Fig. 7B, spectrum b), no other CuB-CO mode was detected even at a ratio of 0.5% of the 2051.0 cm−1 band. The absence of any other than the 2051.0 cm−1 CuB-CO mode in a spectral region with a very high signal-to-noise ratio > 105 reflects the complete absence of reverse electron transfer from the high spin heme a32+ to [(CuA-CuA)3+, heme b3+] upon dissociation of CO from heme a3 Fe2+. If a [(CuA-CuA), Feb]5+, Fea33+, CuB1+-CO complex would be generated instead of the ordinary [(CuA-CuA), Feb]6+, Fea32+, CuB1+-CO, the CuB-CO complex would exhibit a clear different C-O stretching frequency. In particular, the C-O mode would be shifted to lower frequencies (≈2030 cm−1), as the more polar heme a3 Fe3+ would stabilize the Cδ+-Oδ− resonance form of the CO. This result is in contrast to all the other previously examined oxidases, which showed a significant fraction (25–100%) of back electron transfer from heme a3/o3 to the low-spin heme a/b (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Extent of reverse electron transfer followed the CO dissociation from the mixed-valence form of various cytochrome c oxidases

The midpoint redox potentials (versus Standard Hydrogen Electrode) of the hemes are also included. ND, not determined.

| Enzyme | Reverse electron transfer (a3/o3)2+ → (a/b)3+ | Reference | Midpoint redox potential (vs. SHE) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. denitrificans aa3 | 50% at pH 7.0 100% at pH 11.0 |

49 | pH 8.0 heme a: 359 mV heme a3: 350 mV |

69 |

| Bovine heart aa3 | 25–35% at pH 7.5 | 48 | ND | |

| R. sphaeroides aa3 | 100% at pH 7.0 | 50, 52 | ND | |

| E. coli bo3 | 25% at pH 8.0 | 47 | ND | |

| T. thermophilus ba3 | 0% at pH 6.5–8.5 4.2% at pH 7.4 |

This work | pH 7.6 Heme b: 210 mV Heme a3: 430 mV |

58 |

| 38 | pH 7.0 Heme b: 213 mV Heme a3: 285 mV |

59 |

FTIR studies on the MV complex of E. coli bo3 and bovine heart aa3 oxidases have shown that c.w. laser photolysis of the CO-bound form of the enzyme results in an additional transient CuB-CO complex, not present in the FR state, detected at 2046 and 2040 cm−1, respectively (47, 48). The observed frequencies were 21 and 17 cm−1 lower than the main CuB-CO conformer, and the presence of those bands was attributed to the reverse electron transfer from heme a32+/o32+ to heme a3+/b3+. All the vibrational modes associated with the CO-photolysis of the fully reduced and mixed-valence forms of various CcO enzymes are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Vibrational modes associated with CO-photolysis of the fully reduced and mixed valence forms of various cytochrome c oxidases

| Enzyme | FR Form (a3/o3)2+-CO CuB1+ | FR Form (a3/o3)2+ CuB1+-CO | MV Form (a3/o3)2+-CO CuB1+ | MV Form (a3/o3)2+ CuB1+-CO | ET Species (a3/o3)3+ CuB1+-CO | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm−1 | cm−1 | cm−1 | cm−1 | cm−1 | ||

| Bovine heart aa3 | 1963 | 2063 | 1965 | 2061 | 2040 | 48 |

| E. coli bo3 | 1950, 1959 | 2064 | 1951, 1962 | 2063 | 2046 | 47 |

| T. thermophilus ba3 | 1967, 1973, 1982 | 2053 | 1971, 1975, 1983 | 2051 | Not observed | This work |

DISCUSSION

This study is mainly focused on the thermodynamic and kinetic investigation of two distinct forms of cytochrome ba3-CO complex; that is, the fully reduced and the mixed valence. Through them we are also able to monitor possible heme a3 → heme b and CuB → CuA ET processes of the enzyme. FTIR spectroscopy has been proven a structure- and redox-sensitive tool capable of monitoring the redox state of the active sites and their response to an external perturbation such as the photolysis of CO from heme a3. This way we are able to reach physiologically relevant conclusions about the mechanism of action during catalysis.

Binding, Photodissociation, and Recombination Kinetics of CO in ba3-Cytochrome c Oxidase

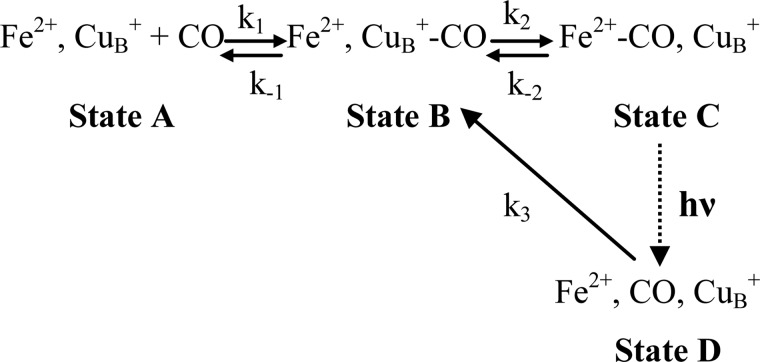

The general aspect of the CO binding, photodissociation, and rebinding kinetics observed by the static FTIR and the time-resolved step-scan FTIR data presented in Figs. 1–7 can be understood through the model depicted in Scheme 3. It should be noted that in cytochrome ba3-CO there is a 25–75% thermal distribution between states B and C not found in any other cytochrome c oxidase. However, the equilibrium CuB1+-CO complex is not photolabile and remains a spectator through the photodissociation rebinding processes of heme a32+-CO complex and formation decay processes of transient CuB1+-CO complex.

SCHEME 3.

In Scheme 3 k1 represents the binding of CO to CuB, and k2 represents its transfer to heme a3 iron. On the other hand, k−1 and k−2 reflect the reverse processes, and k3 reflects the formation of the transient CuB1+-CO complex from the geminate photoproduct (state D), which is expected to be formed in less than 100 fs as found in aa3 oxidase (40, 55).

The five equations that describe kinetically our system are:

|

|

where “Fe” and “Cu” corresponds to heme a3 Fe2+ and CuB1+, and [Fe, Cu-CO] and [Fe-CO, Cu] correspond to the analogous CO-bound complexes. [Fe, Cu]T and [Fe, Cu] symbolize the total enzyme concentration, and the unliganded form of the enzyme and k1obs and k2obs are the experimentally measured rates of the decay of the transient CuB1+-CO complex and of the CO rebinding to heme a3, respectively. In the case of cytochrome ba3, it is known that k−2 = 0.8 s−1, and K1 = 104 m−1 (57). Both values are extremely larger than those found in other heme-copper oxidases (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Kinetics data of various CcOs

| Οxidase | k2obs | K1 | K2 | k1 | k−1 | k2 | k−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | m−1 | m−1s−1 | s−1 | s−1 | s−1 | ||

| Bovine aa3 | 90 | 87 | 4 × 104 | 6 × 107 | 7 × 105 | 1,030 | 0.023 |

| P. denitrificans aa3 | 42 | 53 | 5 × 107 | 1 × 106 | 780 | ||

| E. coli bo | 60 | 400 | 2 × 105 | 500 | 190 | ||

| T. thermophilus. caa3 | 40 | 39,00 | 8 × 107 | 2 × 104 | 50 | ||

| T. thermophilus ba3 | 28.6 | ≈10,000 | 35.8 | ? | ? | 28.6 | 0.8 |

Scheme 3 assumes a priori a rapid equilibrium (K1 = k1/k−1) between states A and B. When this equilibration is rapid relative to all other processes after the very fast formation of state B from state D, the observation of the reformation of state C after the laser-induced photodissociation will be kinetically identical with the direct formation of state C from the unliganded enzyme and CO. The validity of the above assumption can be verified after the determination of the relative rate constants. As we will see below, cytochrome ba3 is the only oxidase where this assumption is solid.

With the assumption k2 ≫ k−2, Equation 1 can be rewritten,

Combining Equations 3, 5, and 6, we reach

|

To reach to the above result, we assumed that states A and B are in equilibrium, so the rate-determining step is K2 = k2/k−2.

When [CO] ≪ 1/K1 (nonsaturation conditions) [Fe, Cu]T ≈ [Fe, Cu], and accordingly Equation 7 leads to:

and Equation 6 can then be transformed to

As [CO] becomes equal to the term 1/K1, our solution exhibits saturation behavior, so Equations 5 and 7 can be rearranged to

Equation 6 can now be rearranged as

In the case of cytochrome ba3-CO, we can assume saturation conditions, as [CO] = 10−3 m; therefore, [CO] ≫ 1/K1 = 10−4 m. So, from Equation 11 and our experimental data, we are in position to calculate rate constant k2.

As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, the decay of the transient CuB1+-CO complex is accompanied by the concomitant rebinding of CO to heme a3, suggesting the absence or decay of any thermodynamic and/or kinetic barrier. For example at pH 7.50 we measure a k1obs of 29.4 s−1 and a k2obs of 24.8 s−1, which is larger than k−2 (0.8 s−1) by a factor of 31, so the previous assumption k2 ≫ k−2 is valid. In addition we do not need to assume that the rate-determining step is the K2 and, therefore, k−1 ≫ k2.

The fast equilibration between states A and B (K1 = 104 m−1) is responsible for the kinetic identification of the two processes leading to the formation of the [Fe-CO, Cu] complex, the one that follows photodissociation (k2obs) and the thermal one (k2). The final result of k2 = k2obs is valid only for cytochrome ba3, as it is the only oxidase that exhibits saturation kinetics behavior under normal CO pressure (1 atm) and temperature (293 K) conditions. The reason for this behavior is the exceptionally high affinity of CuB for CO (K1), in contrast to what has been found to all the other heme-copper oxidases.

Differential Equation 2 cannot be solved due to the large number of unknown parameters. If we make the assumption that the rate-determining step is the K2, then k−1 ≫ k2 ≫ k−2. In addition, due to saturation conditions [Fe, Cu]T ≈ [Fe, Cu-CO] ⇒ [Fe, Cu] ≈ 0. So Equation 2 is simplified to

However, the derived k−1 values do not support the assumption made k−1 ≫ k2 ≫ k−2, and, therefore, cannot be accepted. If we assume that K1 is the rate-determining step, we reach to the same exactly conclusion: k−1 = k1obs + k2obs.

To summarize, in the case of cytochrome ba3-CO, both K1 and K2 are rate-determining steps, as neither can be considered to equilibrate faster than the other. In addition, cytochrome ba3 is the only oxidase that exhibits behavior of saturation kinetics, as [CO] ≫ 1/K1 (Table 3).

Electron Transfer in Cytochrome c Oxidase

Cytochrome c oxidase utilizes a complex pattern of ET through strongly coupled substrate and redox-dependent sites that involve intermediate cofactors and nonadiabatic, long distance, single-electron tunneling between weakly coupled redox centers (5, 11, 45, 46, 66). In the aerobic electron transfer chain of T. thermophilus, electrons are donated by cytochrome c552 and enter ba3-cytochrome c oxidase through the dinuclear CuA site (39, 58, 59, 67). The interactions between this pair were found to be mainly hydrophobic (68), in contrast to other oxidases where an electrostatic character was described. Furthermore, the physiological direction of the reaction is also thermodynamically favorable, as the midpoint Em redox potentials for cytochrome c552 and CuA complex are 200–230 and 240–260 mV (57, 68), respectively. Similar values for the CuA complex have been obtained for the bovine heart and P. denitrificans aa3 oxidases (69). The next step in cytochrome ba3 involves the CuA-heme b electron transport, a reaction thermodynamically unfavorable as the low-spin heme b exhibits a redox potential of 210 mV (58, 59). Calculations with the method of tunneling currents in bovine heart aa3 oxidase suggested that this transfer is mediated through pathways involving the His-157, Gln-151, Cys-149, and Cys-153 CuA ligands and the pair of Arg-449 and Arg-450. The current enters the heme mainly through the ring D propionate group (70).

Electron Transfer between Hemes in Cytochrome ba3 Oxidase

The final step in the ET chain is the transfer to the binuclear center through the heme b-heme a3 pathway. This step is characterized by a high driving force as the midpoint redox potentials of heme a3 and heme b were found to be 430 (58)/285 (59) and 210 mV, respectively. Although these values are highly model-dependent and no cooperative or anticooperative effects were taken into account, the downhill flow of the electrons is secured because of the above-mentioned inverted midpoint potentials. To study this ET step we performed photolysis of the mixed-valence state of cytochrome ba3-CO to follow the possible reverse electron transfer between the hemes as previously shown on aa3 and bo3 oxidases. The data presented in Fig. 7 revealed that no such process takes place in cytochrome ba3, a unique property among the various cytochrome c oxidases examined (39–43). It should be noted that Siletsky et al. (38) also studied the electron backflow in ba3-oxidase using optical spectroscopy at the reduced heme a3 band (445 nm) and electrometric measurements. Although they observed a 4.2% electron redistribution between hemes a3 and b, after CO photolysis those data are in relative agreement with ours in terms that in both studies cytochrome ba3 exhibited a significant reduced reverse electron transfer ratio relative to other heme-copper oxidases.

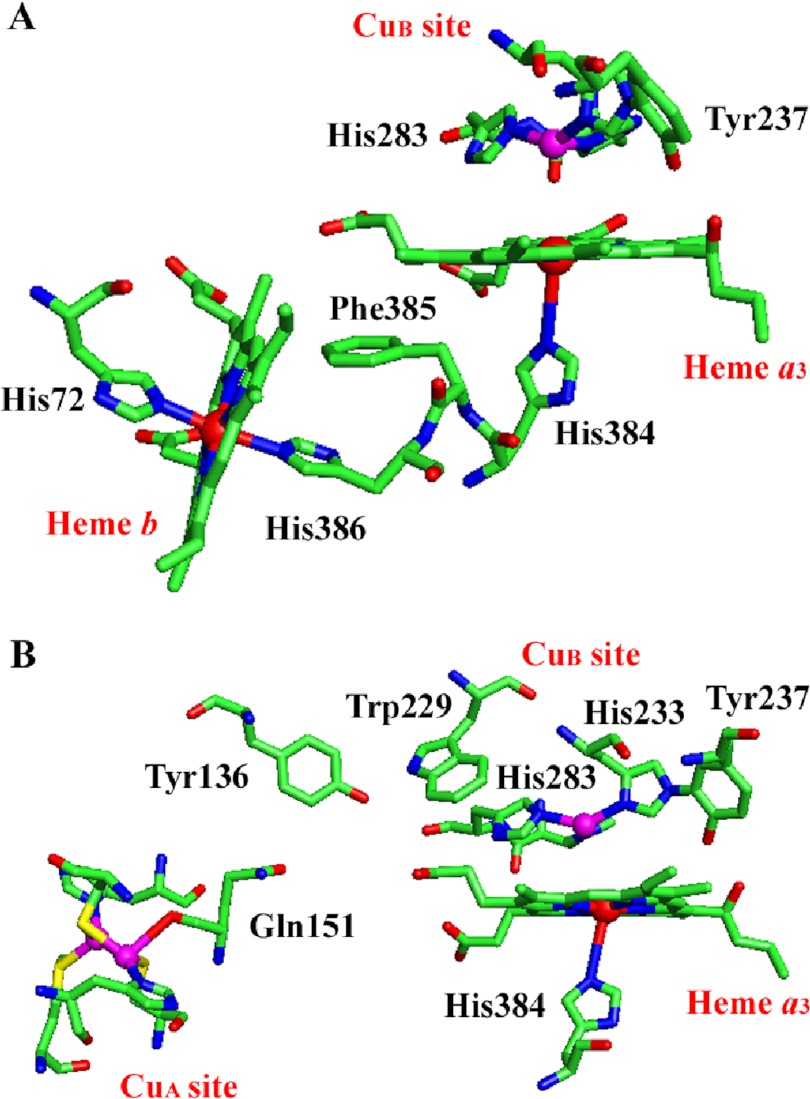

Exploring the reasons for this behavior, the basis of electron transfer in proteins is two or more single- or multi-electron redox centers usually connected through a chain of protein residues, with the three parameters affecting the intra-protein ET rates being the edge-to-edge distance, driving force ΔG, and reorganization energy λ. Heme b and heme a3 are connected through His-386, Phe-385, and His-384 (Fig. 8A) a motif conserved in all the structurally known oxidases. Previous studies on aa3 oxidases have suggested that the dominant ET pathways are through space jumps between the two hemes and through the covalent bonds between His-386, Phe-385, and His-384 (cytochrome ba3 numbering). A comparison among the available crystal structures suggests that these pathways are also operative in cytochrome ba3. Therefore, assuming similar edge-to-edge distances and reorganization energies λ, we attribute the observed difference in the heme b-heme a3 ET process to the high driving force ΔG revealed by the electrochemical titrations of hemes b and a3 (58, 59).

FIGURE 8.

The two proposed electron transfer pathways in cytochrome ba3 oxidase. A, shown is the heme b-heme a3-CuB pathway through His-386, Phe-385, and His-384 residues. The CuA-heme b ET step has been removed for clarity together with the hydroxyethylgeranylgeranyl tail of heme a3. B, shown is the direct CuA-CuB pathway through Gln-151, Tyr-136, Trp-229, and His-283 residues. The CuA, CuB atoms are shown as magenta spheres, and the heme b, heme a3 iron atoms are shown as red spheres respectively. The figure was prepared with PyMOL (PDB accession code 1EHK) (71).

Previous studies on aa3 oxidases revealed either undistinguishable potentials for the two hemes or higher potential for the low-spin heme. In contrast, cytochrome ba3 exhibits inverted potentials of 210 and 285/430 mV for the heme b and a3, respectively. Furthermore, both values are shifted to more positive potentials than other heme b proteins (sperm whale myoglobin 40 mV) and heme a3 containing oxidases (350 mV in P. denitrificans aa3 oxidase) (69). The difference between heme b and heme a3 potentials is due to the presence of a C-8 formyl substituent in heme a3, which is an electron-withdrawing group. The observed shifts to more positive potentials is a result of increasing positive charge on the hemes. This can be achieved by protonation of the heme(s) propionate groups, high hydrophobicity, and alterations of the heme(s) axial ligands. Indeed, subunit I of cytochrome ba3 is buried to an extreme hydrophobic region, having a pI of 10.4 and a net charge of +9 (21). This nonpolar, low-dielectric microenvironment does not allow the heme to receive electron density from water molecules. In addition, spectroscopic studies have shown that the heme b and a3 propionates groups are partially protonated in cytochrome ba3 (34, 58) relative to other aa3 oxidases and also that the heme a3 axial ligand His-384 appears to have a larger Fe-N bond of 3.3 Å (20), preventing a high degree of π back-bonding electron donation to iron. All these three parameters deviate from what is known in other oxidases and have been tuned in such way to raise the positive charge feeling by the hemes. This leads to an increase of the midpoint potentials and stabilization of the reduced state of hemes. During catalysis, heme a3 reduction is further favored due to the high driving force of the heme b-heme a3 ET step, as discussed above.

Direct Electron Transfer from CuA Complex to Heme a3-CuB Binuclear Center

From the first available crystal structure of bovine heart aa3-cytochrome c oxidase, it was suggested that electrons can also be supplied to the binuclear center through a direct transfer from the CuA complex. In addition, Soulimane et al. (20) reporting the x-ray structure of cytochrome ba3 suggested a direct ET from CuA to the binuclear center through a CuA-CuB electron pathway. This pathway, shown in Fig. 8B, involves the CuA ligand Gln-151, Tyr-136, Trp-229, and H283is-, one of the CuB ligands at a distance of 21.6 Å between the two metals. In cytochrome ba3 the CuA complex exhibits a midpoint reduction potential of 250 mV similar to that observed in P. denitrificans aa3 oxidase. The reduction potential of CuB is not known yet; however, according to that determined in aa3 oxidase (412 mV) (69), we expect similar or even higher potential. Therefore, this step if active is characterized by a high driving force. On the other hand, several spectroscopic studies and pathway analysis data suggested that the CuA-CuB ET pathway is not active, presumably due to a long tunneling route between CuA and Tyr-136 and a high reorganization energy. Although cytochrome ba3 is an ideal system to study these events through the equilibrium heme a3 Fe2+-CO and CuB1+-CO modes, the data presented in Fig. 3 rule out the possibility of reverse electron transfer from CuB or heme a3 to CuA. However, the proposal of the forward ET from CuA to CuB or heme a3 still cannot be excluded.

These results show that ba3-cytochrome c oxidase uses a clear different structural pattern of energy conversion for the coupling of the electron transfer/oxygen chemistry and proton pumping processes. This pattern has taken into account all the extreme environmental factors that affect the function of the enzyme and is manufactured in such a way that ensures its effective operation.

This work was supported by Cyprus University of Technology research funds (to C. V.) and Science Foundation Ireland Grant BICF865 (to T. S.).

- ET

- electron transfer

- FR

- fully reduced

- MV

- mixed valence

- CcO

- cytochrome c oxidase

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Marcus R. A., Sutin N. (1985) Electron transfers in chemistry and biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 811, 265–322 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Page C. C., Moser C. C., Chen X., Dutton P. L. (1999) Natural engineering principles of electron tunneling in biological oxidation-reduction. Nature 402, 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Page C. C., Moser C. C., Dutton P. L. (2003) Mechanism for electron transfer within and between proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moser C. C., Page C. C., Farid R., Dutton P. L. (1995) Biological electron transfer. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 27, 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gray H. B., Winkler J. R. (2005) Long-range electron transfer special feature. Long-range electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3534–3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferguson-Miller S., Babcock G. T. (1996) Heme/copper terminal oxidases. Chem. Rev. 96, 2889–2908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Michel H., Behr J., Harrenga A., Kannt A. (1998) Cytochrome c oxidase. Structure and spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27, 329–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Regan J. J., Ramirez B. E., Winkler J. R., Gray H. B., Malmström B. G. (1998) Pathways for electron tunneling in cytochrome c oxidase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 30, 35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tan M. L., Balabin I., Onuchic J. N. (2004) Dynamics of electron transfer pathways in cytochrome c oxidase. Biophys. J. 86, 1813–1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brzezinski P. (1996) Internal electron-transfer reactions in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry 35, 5611–5615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jasaitis A., Rappaport F., Pilet E., Liebl U., Vos M. H. (2005) Activationless electron transfer through the hydrophobic core of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10882–10886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill B. C. (1994) Modeling the sequence of electron transfer reactions in the single turnover of reduced, mammalian cytochrome c oxidase with oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 2419–2425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Than M. E., Soulimane T. (2001) ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus Thermophilus: Handbook of Metalloproteins (Messerschimdt A., Huber R., Poulos T., Wieghardt K., eds) pp. 363–378, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zimmermann B. H., Nitsche C. I., Fee J. A., Rusnak F., Münck E. (1988) Properties of a copper-containing cytochrome ba3, a second terminal oxidase from the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 5779–5783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giuffrè A., Stubauer G., Sarti P., Brunori M., Zumft W. G., Buse G., Soulimane T. (1999) The heme-copper oxidases of Thermus thermophilus catalyze the reduction of nitric oxide. Evolutionary implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14718–14723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pinakoulaki E., Ohta T., Soulimane T., Kitagawa T., Varotsis C. (2005) Detection of the His-heme Fe2+-NO species in the reduction of NO to N2O by ba3-oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 15161–15167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pilet E., Nitschke W., Rappaport F., Soulimane T., Lambry J. C., Liebl U., Vos M. H. (2004) NO binding and dynamics in reduced heme-copper oxidases aa3 from Paracoccus denitrificans and ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry 43, 14118–14127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayashi T., Lin I. J., Chen Y., Fee J. A., Moënne-Loccoz P. (2007) Fourier transform infrared characterization of a CuB-nitrosyl complex in cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. Relevance to NO reductase activity in heme-copper terminal oxidases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14952–14958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Radzi Noor M., Soulimane T. (2012) Bioenergetics at extreme temperature. Thermus thermophilus ba3- and caa3-type cytochrome c oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 638–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soulimane T., Buse G., Bourenkov G. P., Bartunik H. D., Huber R., Than M. E. (2000) Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 19, 1766–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keightley J. A., Zimmermann B. H., Mather M. W., Springer P., Pastuszyn A., Lawrence D. M., Fee J. A. (1995) Molecular genetic and protein chemical characterization of the cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20345–20358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hunsicker-Wang L. M., Pacoma R. L., Chen Y., Fee J. A., Stout C. D. (2005) A novel cryoprotection scheme for enhancing the diffraction of crystals of recombinant cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61, 340–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu B., Chen Y., Doukov T., Soltis S. M., Stout C. D., Fee J. A. (2009) Combined microspectrophotometric and crystallographic examination of chemically reduced and x-ray radiation-reduced forms of cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Structure of the reduced form of the enzyme. Biochemistry 48, 820–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iwata S., Ostermeier C., Ludwig B., Michel H. (1995) Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature 376, 660–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsukihara T., Aoyama H., Yamashita E., Tomizaki T., Yamaguchi H., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yaono R., Yoshikawa S. (1996) The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 Å. Science 272, 1136–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ostermeier C., Harrenga A., Ermler U., Michel H. (1997) Inaugural article. Structure at 2.7 Å resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody FV fragment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10547–10553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Svensson-Ek M., Abramson J., Larsson G., Törnroth S., Brzezinski P., Iwata S. (2002) The x-ray crystal structures of wild-type and EQ(I-286) mutant cytochrome c oxidases from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Mol. Biol. 321, 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoshikawa S., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yaono R., Yamashita E., Inoue N., Yao M., Fei M. J., Libeu C. P., Mizushima T., Yamaguchi H., Tomizaki T., Tsukihara T. (1998) Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science 280, 1723–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsukihara T., Shimokata K., Katayama Y., Shimada H., Muramoto K., Aoyama H., Mochizuki M., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Yamashita E., Yao M., Ishimura Y., Yoshikawa S. (2003) The low-spin heme of cytochrome c oxidase as the driving element of the proton-pumping process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15304–15309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abramson J., Riistama S., Larsson G., Jasaitis A., Svensson-Ek M., Laakkonen L., Puustinen A., Iwata S., Wikström M. (2000) The structure of the ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli and its ubiquinone binding site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 910–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lyons J. A., Aragão D., Slattery O., Pisliakov A. V., Soulimane T., Caffrey M. (2012) Structural insights into electron transfer in caa3-type cytochrome oxidase. Nature 487, 514–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buschmann S., Warkentin E., Xie H., Langer J. D., Ermler U., Michel H. (2010) The structure of cbb3 cytochrome oxidase provides insights into proton pumping. Science 329, 327–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang H. Y., Hemp J., Chen Y., Fee J. A., Gennis R. B. (2009) The cytochrome ba3 oxygen reductase from Thermus thermophilus uses a single input channel for proton delivery to the active site and for proton pumping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16169–16173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koutsoupakis K., Stavrakis S., Pinakoulaki E., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2002) Observation of the equilibrium CuB-CO complex and functional implications of the transient heme a3 propionates in cytochrome ba3-CO from Thermus thermophilus. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and time-resolved step-scan FTIR studies. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32860–32866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koutsoupakis C., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2004) Probing the Q-proton pathway of ba3-cytochrome c oxidase by time-resolved Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 86, 2438–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kannt A., Soulimane T., Buse G., Becker A., Bamberg E., Michel H. (1998) Electrical current generation and proton pumping catalyzed by the ba3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. FEBS Lett. 434, 17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gomes C. M., Backgren C., Teixeira M., Puustinen A., Verkhovskaya M. L., Wikström M., Verkhovsky M. I. (2001) Heme-copper oxidases with modified D- and K-pathways are yet efficient proton pumps. FEBS Lett. 497, 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siletsky S. A., Belevich I., Jasaitis A., Konstantinov A. A., Wikström M., Soulimane T., Verkhovsky M. I. (2007) Time-resolved single-turnover of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1383–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Szundi I., Funatogawa C., Fee J. A., Soulimane T., Einarsdóttir O. (2010) CO impedes superfast O2 binding in ba3 cytochrome oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21010–21015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Einarsdóttir O., Dyer R. B., Lemon D. D., Killough P. M., Hubig S. M., Atherton S. J., López-Garriga J. J., Palmer G., Woodruff W. H. (1993) Photodissociation and recombination of carbonmonoxy cytochrome oxidase. Dynamics from picoseconds to kiloseconds. Biochemistry 32, 12013–12024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fee J. A., Case D. A., Noodleman L. (2008) Toward a chemical mechanism of proton pumping by the B-type cytochrome c oxidases. Application of density functional theory to cytochrome ba3 of Thermus thermophilus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15002–15021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nicholls P., Soulimane T. (2004) The mixed valence state of the oxidase binuclear centre. How Thermus thermophilus cytochrome ba3 differs from classical aa3 in the aerobic steady state and when inhibited by cyanide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1655, 381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Daskalakis V., Farantos S. C., Guallar V., Varotsis C. (2011) Regulation of electron and proton transfer by the protein matrix of cytochrome c oxidase. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 3648–3655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brzezinski P., Malmström B. G. (1985) The reduction of cytochrome c oxidase by carbon monoxide. FEBS Lett. 187, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pilet E., Jasaitis A., Liebl U., Vos M. H. (2004) Electron transfer between hemes in mammalian cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16198–16203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Verkhovsky M. I., Jasaitis A., Wikström M. (2001) Ultrafast haem-haem electron transfer in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1506, 143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Prutsch A., Vogtt K., Ludovici C., Lübben M. (2002) Electron transfer at the low-spin heme b of cytochrome bo3 induces an environmental change of the catalytic enhancer glutamic acid 286. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1554, 22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okuno D., Iwase T., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Yoshikawa S., Kitagawa T. (2003) FTIR detection of protonation/deprotonation of key carboxyl side chains caused by redox change of the CuA-heme a moiety and ligand dissociation from the heme a3-CuB center of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7209–7218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rost B., Behr J., Hellwig P., Richter O. M., Ludwig B., Michel H., Mäntele W. (1999) Time-resolved FT-IR studies on the CO adduct of Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c oxidase. Comparison of the fully reduced and the mixed valence form. Biochemistry 38, 7565–7571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Adelroth P., Brzezinski P., Malmström B. G. (1995) Internal electron transfer in cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 34, 2844–2849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Belevich I., Tuukkanen A., Wikström M., Verkhovsky M. I. (2006) Proton-coupled electron equilibrium in soluble and membrane-bound cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochemistry 45, 4000–4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Szundi I., Ray J., Pawate A., Gennis R. B., Einarsdóttir O. (2007) Flash-photolysis of fully reduced and mixed-valence CO-bound Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c oxidase. Heme spectral shifts. Biochemistry 46, 12568–12578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Einarsdóttir O., Killough P. M., Fee J. A., Woodruff W. H. (1989) An infrared study of the binding and photodissociation of carbon monoxide in cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 2405–2408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Goldbeck R. A., Einarsdóttir O., Dawes T. D., O'Connor D. B., Surerus K. K., Fee J. A., Kliger D. S. (1992) Magnetic circular dichroism study of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. Spectral contributions from cytochromes b and a3 and nanosecond spectroscopy of carbon monoxide photodissociation intermediates. Biochemistry 31, 9376–9387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woodruff W. H. (1993) Coordination dynamics of heme-copper oxidases. The ligand shuttle and the control and coupling of electron transfer and proton translocation. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25, 177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pinakoulaki E., Ohta T., Soulimane T., Kitagawa T., Varotsis C. (2004) Simultaneous resonance Raman detection of the heme a3-Fe-CO and CuB-CO species in CO-bound ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Evidence for a charge transfer CuB-CO transition. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22791–22794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Giuffrè A., Forte E., Antonini G., D'Itri E., Brunori M., Soulimane T., Buse G. (1999) Kinetic properties of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Effect of temperature. Biochemistry 38, 1057–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hellwig P., Soulimane T., Buse G., Mäntele W. (1999) Electrochemical, FTIR, and UV/visible spectroscopic properties of the ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry 38, 9648–9658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sousa F. L., Veríssimo A. F., Baptista A. M., Soulimane T., Teixeira M., Pereira M. M. (2008) Redox properties of Thermus thermophilus ba3. Different electron-proton coupling in oxygen reductases? Biophys. J. 94, 2434–2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Glasoe P. K., Long F. A. (1960) Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 64, 188–190 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Alben J. O., Moh P. P., Fiamingo F. G., Altschuld R. A. (1981) Cytochrome oxidase (a3) heme and copper observed by low-temperature Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of the CO complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 234–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Koutsoupakis K., Stavrakis S., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2003) Oxygen-linked equilibrium CuB-CO species in cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Implications for an oxygen channel at the CuB site. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14893–14896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Iwaki M., Rich P. R. (2007) An IR study of protonation changes associated with heme-heme electron transfer in bovine cytochrome c oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2923–2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Koutsoupakis C., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2003) Docking site dynamics of ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36806–36809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Koutsoupakis C., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2003) Ligand binding in a docking site of cytochrome c oxidase. A time-resolved step-scan Fourier transform infrared study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14728–14732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kaila V. R., Verkhovsky M. I., Wikström M. (2010) Proton-coupled electron transfer in cytochrome oxidase. Chem. Rev. 110, 7062–7081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Farver O., Chen Y., Fee J. A., Pecht I. (2006) Electron transfer among the CuA-, heme b-, and a3-centers of Thermus thermophilus cytochrome ba3. FEBS Lett. 580, 3417–3421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Maneg O., Ludwig B., Malatesta F. (2003) Different interaction modes of two cytochrome c oxidase soluble CuA fragments with their substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46734–46740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gorbikova E. A., Vuorilehto K., Wikström M., Verkhovsky M. I. (2006) Redox titration of all electron carriers of cytochrome c oxidase by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry 45, 5641–5649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Medvedev D. M., Daizadeh I., Stuchebrukhov A. A. (2000) Electron transfer tunneling pathways in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 6571–6582 [Google Scholar]

- 71.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4 Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]