Abstract

Background

Neurolinguistic programming (NLP) in health care has captured the interest of doctors, healthcare professionals, and managers.

Aim

To evaluate the effects of NLP on health-related outcomes.

Design and setting

Systematic review of experimental studies.

Method

The following data sources were searched: MEDLINE®, PsycINFO, ASSIA, AMED, CINAHL®, Web of Knowledge, CENTRAL, NLP specialist databases, reference lists, review articles, and NLP professional associations, training providers, and research groups.

Results

Searches revealed 1459 titles from which 10 experimental studies were included. Five studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and five were pre-post studies. Targeted health conditions were anxiety disorders, weight maintenance, morning sickness, substance misuse, and claustrophobia during MRI scanning. NLP interventions were mainly delivered across 4–20 sessions although three were single session. Eighteen outcomes were reported and the RCT sample sizes ranged from 22 to 106. Four RCTs reported no significant between group differences with the fifth finding in favour of the NLP arm (F = 8.114, P<0.001). Three RCTs and five pre-post studies reported within group improvements. Risk of bias across all studies was high or uncertain.

Conclusion

There is little evidence that NLP interventions improve health-related outcomes. This conclusion reflects the limited quantity and quality of NLP research, rather than robust evidence of no effect. There is currently insufficient evidence to support the allocation of NHS resources to NLP activities outside of research purposes.

Keywords: experimental designs; neurolinguistic programming; primary care; review, systematic; treatment effectiveness

INTRODUCTION

Neurolingistic programming (NLP) is an emerging technology within health care attracting interest and investment, particularly within primary care. NLP is a communication framework using techniques to understand and facilitate change in thinking and behaviour. Early study of NLP was of a scholarly nature and promoted NLP as a psychotherapeutic technique, although publication of commercial works1,2 in the 1980s signalled a move between the academic and commercial worlds. While there is no agreed definition of NLP, different formulations share (or practitioners accept) a set of core propositions. In particular, NLP proposes that our internal representations of the world show a bias for a particular sensory modality (visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, olfactory or gustatory), and that a person’s dominant modality, or preferred representational system (PRS), is signalled through various behavioural indices, particularly verbal expression and eye movement. A visual person, for example, may say ‘I see what you mean’ whereas an auditory thinker may say ‘I hear what you say’. The central tenet, or hypothesis of NLP is that communication will be more effective, or persuasive, if it is tailored to match the PRS of the target person. NLP practitioners use the individual’s PRS as a foundation to the development of rapport, to facilitate modelling, elicit well formed outcomes and use anchoring (or conditioning) techniques. NLP training is informally regulated in the UK, through the Association of NLP (ANLP)3 and internationally through the International NLP Trainer’s Association (INLPTA)4 at three levels of diploma, practitioner, and master practitioner, based on the number of hours of study and practice.3,4 While NLP training organisations and practitioner registers are internationally widespread with NLP training opportunities for business use, personal development, and health visible in many European countries, US, Canada, and Australia,3–6 the targeting of medical and healthcare practitioners for such training by NLP organisations in the form of seminars, workshops, and literature appears to be presently focused on the UK.7–10

This targeted interest by the NLP community in medical and healthcare professionals led the authors to make a UK Freedom of Information (FOI) request to NHS organisations to identify spending on NLP training or services over a 3-year period. Information was requested on the purpose of any training (for example, personal development, management training, clinical service provision), which staff were trained and whether any associated evaluations or audits had been undertaken. This request was sent in June 2009 to all 143 primary care trusts, 73 mental health trusts, 166 hospital trusts, 12 ambulance trusts, 10 care trusts, and 10 strategic health authorities. A total of 326 (79%) NHS organisations responded to the request and the unpublished data revealed an NHS monetary spend of £802 468 on NLP-related activity. Over 700 NHS staff undertook NLP training during the time period with the majority (75%) being in administrative/managerial roles. Clinical staff included counsellors and clinical psychologists. A conservative estimate of 1-day training per person was determined at a modest daily salary rate of £150 per person indicates an estimated training cost of £105 000. For five trusts reporting that they had developed NLP-based services, the majority was spent on weight-loss counselling (£200 000) and this was a research study. Other spend areas included counselling skills (£190), substance misuse counselling (£90) and smoking cessation services (£450). While this spend was found to be modest, the FOI request established that it was widespread.

How this fits in

Neurolinguistic programming (NLP) is a collection of communication and behaviour change techniques used within the NHS for both clinical and managerial purposes and has a reputation in the business and entertainment industry as a method for influencing people. NLP is promoted to health professionals as a therapeutic and managerial intervention. Limited experimental research has been undertaken into the use of NLP to influence health outcomes and there is little evidence that NLP interventions improve health outcomes based on poor quality studies across heterogeneous conditions and populations. The allocation of NHS resources to support NLP activities should be confined to research investigations.

NLP’s position outside mainstream academia has meant that while the evidence base for psychological intervention in both physical and mental health has strengthened,11–14 parallel evidence in relation to NLP has been less evident and has attracted academic criticism.15,16 No systematic review of the NLP literature has been undertaken applying Cochrane methods.17 The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic literature review and appraise the available evidence for effectiveness of NLP on health-related outcomes.

METHOD

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported primary research on the effects of NLP on any health-related outcomes in all clinical populations. Studies without a quantitative evaluation of the effect of NLP, single case (n = 1) studies, and those in which a single NLP technique was evaluated were excluded. Language eligibility was restricted to English.

MEDLINE® Ovid version (1950 to 20/02/12), PsycINFO (Earliest to 20/02/12), Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (Earliest to 20/02/12), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) (1985 to 20/02/12), CINAHL® (1981 to 20/02/12), Web of Knowledge (Earliest to 20/02/12) and CENTRAL (Earliest to 20/02/12) were searched. The following keywords ‘neurolinguistic/neuro-linguistic and neuro linguistic programming’ were combined using the ‘OR’ Boolean operator together with the MeSH heading ‘neurolinguistic programming’ (available for MEDLINE only). The specialist NLP databases at the Universities of Bielefeld and Surrey (to 20/02/12), and the European Association for Neuro-linguistic Psychotherapy (to 20/02/12) were also searched in their entirety, and NLP associations, research groups, and social network forums, were contacted for additional research. Reference lists were screened for additional citations. A single reviewer initially screened all search results by title and those deemed potentially relevant were assessed against the eligibility criteria by two reviewers independently, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. Full-text papers of included studies were assessed against the eligibility criteria by two reviewers independently and discrepancies were resolved through discussion or referral to a third reviewer.

A data extraction template was developed, pilot-tested on two papers by three reviewers, and modified as necessary. Two reviewers independently extracted data from each study, including: publication details (authors, year, and country), participant characteristics, intervention details, outcome measures, risk of bias, and study findings. Risk of bias assessment for the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was undertaken with reference to the Cochrane Handbook.17 The RCTs were assessed against the four risk domains of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, and incomplete outcome data. The risk of bias was assessed based on the reported study methods according to the following criteria; low risk of bias = all domains adequately met, high risk of bias = at least one domain not met and uncertain risk of bias = inadequate reporting of methods.17 Risk of bias for the pre-post studies was assessed using the Downs & Black quality index score. This is a validated checklist for assessing the quality of randomised and non-randomised studies in five subscales: reporting, external validity, internal validity (bias and confounding), and power.18

RESULTS

Available evidence

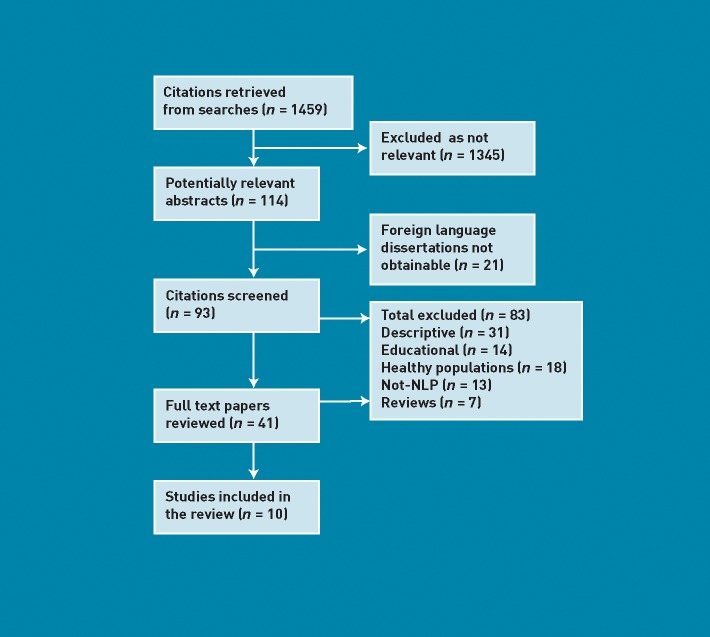

A total of 1459 citations were retrieved using the search strategy. Of these, 93 titles were potentially relevant (Figure 1). Abstracts were obtained and screened and 41 full text papers reviewed. Of the initial 93 citations, the majority were excluded as they were descriptive in nature, were not NLP interventions or they involved only healthy populations. In total, 10 studies were identified meeting the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Due to the small number of studies identified and heterogeneity (in research design, populations, NLP interventions, and assessed outcomes), statistical analysis was not appropriate and a narrative synthesis of the evidence was undertaken. Nine studies were published in peer-reviewed journals and one was identified online.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of identified studies.

Table 1.

Details of included studies

| Author, country and health issue | Study design and setting | Population and participants | NLP Intervention details | Assessed outcomes and measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised Controlled Trials | |||||

| Krugman et al

19 US Speech anxiety |

Design: RCT Setting: University Assessmen: Baseline and immediately post-treatment Groups: arm 1) NLP single session; arm 2) self-controlled desensitisation; arm 3) waiting list control |

Participants: university undergraduate students Recruitment: response to advertisement for a programme to alleviate anxiety in public speaking situations. Study baseline, n = 55, 28 male/27 female. Numbers randomised, analysed and completed not reported Single session |

NLP interventionist training: three graduate clinical/counselling psychologists with additional 4 months of NLP training. Training fidelity checks employed NLP intervention: phobia intervention from ‘Frogs into Princes’:2 Kinaesthetic Anchoring techniques, visualisation |

Public speech anxiety. Personal Report of Confidence as a Speaker Scale. Paul’s Modified Behaviour Checklist. Observed global rating of speech anxiety |

Between group differences; no statistical difference between groups (results data not reported). Within group differences (pre-post tests): t values (pre-post tests): t values attained statistical significance (P<0.05) showing reduction in all measures of speech anxiety (including fear expectancy and fear survey) in all three arms. |

| de Miranda et al

20 Brazil Maternal emotional disturbance and child emotional development |

Design: RCT. Setting: day care centre. Assessment: baseline and 9 months post-intervention. Groups: arm 1) NLP; arm 2) control, no further description | Participants: mother and infant pairs. Mothers’ age unreported, child age 18–36 months, sex unreported. Recruitment: not described. Randomised n = 45 (23 NLP/22 control). Completed n = 37. Analysed: children n = 27, mothers n = 37 (10 NLP/27 control) | NLP interventionist training: not described. NLP intervention: arm 1) not described beyond ‘NLP’, 15 sessions over 1 year | Child development (Bayley scale). Home environment variation (Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment [HOME] questionnaire). Maternal Mental Health (Self Report Questionnaire) | Between Groups: Non-significant trend towards improvement in the HOME environment (P = 0.09). Variations in child mental development (OR 1.21, 95% CI = 0.0 to 23.08, P = 0.669). Maternal mental health: P = 0.26. |

| Stipancic et al21 Croatia Psychological difficulties | Design: RCT waiting list controlled trial alternately allocated. Setting: private psychotherapy practice. Assessments: arm 1) baseline, post-treatment and 5 months post-treatment. Arm 2) baseline, 3 months. Groups: arm 1) NLP psychotherapy, arm 2) Wait list control | Participants: self-referred for psychological difficulties to ‘reduced rate’ psychotherapy: 79% female <21 years = 9%; 21–40 years = 59% >40 years = 31%. Married 24%; employed 56%; college educated or higher 100%. Recruitment: multiple methods. Alternately allocated n = 106 (54 int/52 wait list) Number completed not reported. Analysed n = 54 in int group. Control group analyses not reported. | NLP interventionist training: Seven psychotherapists trained to NLP master practitioner level. NLP intervention: individual neurolinguistic psychotherapy (NLPt). Weekly x 60 min sessions. Mean n = 20 (range 5–65). | Baseline/screening structured clinical interviews for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Croatian scale of Quality of Life | Between groups: ANOVA test found NLP arm resulted in QOL improvement and decreased clinical symptoms (F = 8.114, P = 0.000). Within group findings at 5 months found improvement in intervention compared to baseline (F=3.672, P = 0.019. A small significant interaction was found between number of sessions and size of improvement. |

| Sorensen et al 22 Denmark Weight maintenance | Design: RCT. Setting: weight loss clinic. Assessment: baseline pre randomisation, post intervention and at 2 and 3 years. Groups: arm 1) NLP therapy, arm 2) a course in gourmet cookery | Participants: overweright or obese adults aged 25–55 years. Recruitment: At weight loss clinic following >8% weight loss during 12-week programme. Number in study: randomised n = 48 (23 to NLP, 25 cookery); completed n = 41 (17 NLP, 24 cookery); analysed at 3 years n = 34 (16 NLP, 18 cookery) | NLP interventionist training: experienced NLP practitioner (certified by Danish NLP institute). NLP intervention: NLP course arm 1) 10 sessions over 5 months, arm 2) 10 sessions over 5 months | Fasting weight in light clothes to nearest 0.1kg on digital scales | Between groups: during the 5 months of treatment, there was no significant difference observed between groups for additional weight lost: NLP: –1.8kg versus cookery course: –0.2kg (ANCOVA, NS). After 3 years 57% in the NLP group and 50% in the cookery group had maintained a part of their initial weight loss. There was no significant difference observed between groups (ANCOVA) |

| Simpson and Dryden23 UK Panic Disorder | Design: equivalence randomised trial. Setting not reported. Assessments: screening, baseline post randomisation, immediately at intervention completion and 4 weeks post completion. Groups: Arm 1) REBT, arm 2) VKD (NLP arm) | Participants: adults meeting DSM-IV criteria for panic disorder age range 23–65 years. Recruited via media advert. Randomised n = 22, completed n = 18, (12 females/6 males) nine in each arm. Mean duration = 9.52 years. Follow-up numbers | NLP interventionist: trained hypnotherapist (registered with UK Council for Psychotherapists as a hypno-psychotherapist) NLP Intervention: VKD also known as Fast Phobia technique. Four sessions at weekly intervals | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire (ACQ) Panic Attack Symptoms Questionnaire (PASQ) Global Panic Rating (GPR) | Between groups: 4 week follow-up — no between group differences: HADS depression: F = 0.106, P = 0.749 HADS anxiety: F = 0.003, P = 0.96; ACQ: F = 0.374, P = 0.549; PASQ: F = 0.659, P = 0.429; GPR: F = 3.586, P = 0.076. There was a greater change in the pre-post scores for the VKD arm as follows pre-post intervention: GPR 18.78 reduced to 4.78; PASQ 74.78 reduced to 30.67; ACQ 2.37 reduced to 1.48; HADS anxiety 15.56 reduced to 7.11; HADS depression 9.67 reduced to 4.89 |

| Pre-Post Study Design (uncontrolled) | |||||

| Einspruch and Forman24 US Phobia | Design: pre-post design. Setting: phobia and anxiety outpatient clinic. Assessment: baseline and 8 weeks | Participants: people with simple or multiple phobias. Mean age 44 years. Male 29%. Mostly college educated. Recruitment: not reported. Baseline and number completed not reported. Analysed n = 48: group, n = 31, individual n = 17. NB: Reports only those who completed both baseline and follow-up assessments | NLP Interventionist training: not reported. NLP intervention: group or individual intervention according to assessed need. Individual: mean 2.8 sessions per person. Duration not stated. Group: weekly 2-hour sessions for 8 weeks plus three one-to-one sessions | Mark’s Phobia questionnaire and Beck Depression Inventory | 16/17 individual participants and 27/29 group participants reported reduced phobia severity at follow-up (both P =<0.01). Group participants reported statistically significant improvements in depression scores (M=3.26; t = 5.18, P = <0.001), 27/29 reported reduced severity. |

| Timpany25 New Zealand Morning sickness in pregnancy | Design: pre-post. Setting: therapist office. Baseline and follow-up assessment. Follow-up time unreported | Participants: women with moderate to severe morning sickness. Recruitment: press advert. Baseline n = 12, completed n =12 analysed n =12. Single 2-hour session | NLP interventionist training: NLP trainer. NLP intervention: combination of NLP time line therapy, well-formed outcomes/goal setting and hypnotherapy | Percentage of time feeling nauseous. Number of vomiting episodes per day. Stress (unreported measure) | 50% of women felt a significant reduction in symptoms in the week after the session. Four women went from feeling nauseous 100% of the time to 20% of the time and two women from 100% to 40%. 5/8 women who had been vomiting noted improvement |

| Konefal and Duncan26 Denmark Social anxiety | Design: pre-post. Setting: residential training course. Assessment: baseline (T0), post intervention (T1) and 6 months (T2) | Participants: people with self-reported social anxiety. 15 male and 13 female), aged 20–60 years. Recruitment not reported. Baseline 28, completed = not reported, analysed n = 23 | NLP interventionist training: not stated NLP intervention: 15 skills and techniques detailed. Residential 21-day programme | Liebowitz Social Phobia Scale | Social anxiety fear T0 M = 20.3 (SE 1.8); T1 M =12.9 (SE2.0); not reported, analysed n = 23 T2 M = 12.4 (SE1.7). Fear avoidance T0 = 20.1 (SE1.7), T1 = 14.5 (SE2.2), T2 = 14.0 (SE2.2). These findings were statistically different from T0 to T1 (P<0.001), but not statistically significant from T1 to T2 |

| Gray27 US Substance misuse | Design: pre-post. Setting: community. Assessments: baseline and 16 weeks | Participants: substances mis-users. Recruitment: compulsory attendance. through criminal justice system. Baseline n = 127 of which 99 described as valid cases. Completed n = 80, analysed n = 99 | NLP interventionist training: not stated. NLP intervention: visualisation, anchoring, well-formed outcomes 2-hour weekly group session and two one-on-one sessions over 16 weeks | Urinalysis for illegal substances | Non-significant difference between completers and non-completers. Abstinence after programme: completers = 55%; non-completers: 16% |

| Bigley et al 28 UK Claustrophobic patients undergoing MRI | Design: pre-post. Setting: NHS radiography department. Assessment: on day of NLP session and follow up on day of MRI prior to scan. Time lag unreported | Participants: patients who had previously failed to undergo MRI. 24 males/26 females. Median age 52 years (range 17–75) Recruitment: NHS radiography department. Baseline n = 50, completed n = 50, analysed n = 50 | NLP interventionist training: MRI radiographer with NLP practitioner training. NLP intervention: ‘Clare’s fast phobia cure’: collapsing anchor, stacked anchor. Single session of 1 hour duration | Successfully completed MRI. Anxiety measured by adapted Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | 38 patients (76%) successfully completed MRI. A further nine (18%) went into the scanner but image was of insufficient quality. Anxiety scores significantly reduced after NLP in all participants, but no statistical difference between those completing MRI or not (P = 0.172). Cost saving of £319 per MRI examination of MRI with NLP vs MRI under general anaesthetic |

NLP = neurolinguistic programming. OR = odds ratio. RCT = randomised controlled trial. REBT = rational emotive behaviour therapy. VKD = visual kinaesthetic dissociation.

Characteristics of included studies

Five studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs)19–23 and five were observational/ pre-post test studies.24–28 These were conducted in the US,3 Denmark,2 UK,2 Croatia, Brazil, and New Zealand. Targeted health conditions include various anxiety disorders,6 weight maintenance, morning sickness, substance misuse, and claustrophobia during MRI. The five RCTs targeted anxiety disorders,3 maternal anxiety/child development and weight maintenance. Two used NLP interventions versus a no-intervention control arm and three compared NLP to an active intervention. Within the five RCTs, follow-up occurred immediately following a single session treatment, at 1 month, 5 months, 9 months and 3 years.

Within the 10 included studies participants were recruited broadly from childcare, criminal justice, and public and private healthcare facilities, higher education and the press. Demographic data about participants was poorly reported with eight studies reporting some data on sex. Two of these studies specifically recruited women only and the six remaining reported data indicating that overall 64% of study participants were female. Six studies reported participant age, albeit inexactly, with a range from 17–75 years and a mid-range estimate of approximately 40 years. One of the RCTs21 presented broader socioeconomic data and found participants to be college educated or higher (100%), married (24%), and employed (56%).

Interventions

Delivery of NLP interventions ranged from three studies using a single 1–2 hour session19,25,28 to the remainder offering 4–20 1–2 hour sessions. Duration of intervention was reported by six studies ranging from 4 weeks,23 21 days residential,26 4–5 months22,27 and 12 months.20 One study offered group NLP.24

Six studies described the qualifications and training of the interventionists and these included three clinical psychologists,19 eight psychotherapists,21,23 a certified NLP practitioner22,25 and an NLP practitioner level radiographer.28 These NLP interventionists were all certified to a minimum of NLP practitioner level with two stated as being master practitioner certified.21,25 The interventionist training level was better described in the RCTs. Intervention techniques reported were mixed with six studies19,23,25–28 employing a well-established NLP intervention described in the NLP literature.29,30 Four studies referred generally to ‘NLP techniques’ or ‘NLP behaviour modification’. The observational studies provided greater detail about the interventions employed.

Outcomes

Across the 10 studies, 23 measures were used, and 18 outcomes reported. Outcomes were largely aligned to the targeted condition and the most common outcome assessed was anxiety19,23–26,28 with three also measuring quality of life23 and depression.23,24 Validated measures were referenced by seven studies with a further two reporting the outcome was assessed but not how. All psychological outcome measures were different across these eight studies. Only three studies measured objective outcomes, weight,22 successful completion of MRI scan,28 and urinalysis for illegal substances.27 Of the 18 outcomes reported, 11 were self-reported, three were objective measures, two were observed, and two not reported. The two observed measures were from RCTs19,20 and one had a blinded outcome assessor19 and the other was unclear.20 In general the RCTs performed no better than the pre-post studies in terms of reporting of outcomes and the process of their measurement.

Risk of bias

In three of the RCTs, the risk of bias was high with alternate group allocation,21,23 and incomplete outcome data reporting20 (Table 2). In two RCTs the risk of bias was uncertain.19,21 None reported results by intention to treat (ITT) analysis and, although one22 reported undertaking ITT analysis, only the completer analysis was presented. Three RCTs fared better in reporting withdrawals and participants lost to follow-up. In the pre-post study designs, the quality index scores18 ranged from 6–13 (maximum rating is 23 for non RCTs) where low ratings represent poor quality. Only one paper28 scored above the scale mid-point for quality.

Table 2.

Assessment of risk of bias

| RCTs | Adequate sequence generation? | Allocation concealment? | Blinding (of outcome assessors)? | Incomplete outcome data addressed? | Overall assessment of risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krugman et al19 | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Uncertain |

| De Miranda et al20 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | High |

| Stipancic et al21 | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Sorensen et al22 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Uncertain |

| Simpson and Dryden23 | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Pre-post study designs | Reporting (10 items) | External validity (3 items) | Internal validity: bias & confounding (13 items) | Power (1 item) | Total score (27 items) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Einspruch and Forman24 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Timpany25 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Konefal and Duncan26 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 10 |

| Gray27 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| Bigley et al28 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 13 |

RCT = randomised controlled trial.

NLP effects

Across the five RCTs, NLP was evaluated with undergraduate students, mother and child pairs, weight challenged adults, and emotionally-distressed adults for which the main outcomes were assessed ranging from immediately post-treatment to 3-year follow-up. Main outcomes reported were anxiety (self-report), child development (observed), weight (objective), and quality of life (self-report). Four RCTs reported no significant between group differences in the assessed outcomes with the fifth21 reporting less psychological distress and increased perceived quality of life in the NLP group compared to the waiting list control arm. Three RCTs and five pre-post studies reported within group improvements. Of the three studies measuring objective outcomes, one reported a post-treatment increase in completed MRI scans28 and the other two reported no post-treatment improvement in urinalysis for illegal substances27 or weight maintenance.22

DISCUSSION

Summary

This systematic review demonstrates that there is little evidence that NLP interventions improve health-related outcomes. The study conclusion reflects the limited quantity and quality of NLP research, rather than robust evidence of no effect.

Strengths and limitations

This represents the first well-conducted review investigating the effectiveness of NLP on health-related outcomes. The study has not attempted to define NLP and its many components and techniques and this complicates the interpretation of the evidence. This study took the authors’ word that they were delivering NLP if they said they were and the evidence of levels of training of the interventionist supported this assumption. Some academic investigation into NLP was found in unpublished German language dissertations that the library advised would not be possible to obtain and this represents a possible gap in the evidence. The decision was taken to exclude studies using single NLP techniques. NLP has a lack of consensus surrounding a definition of techniques and mechanism of effect and on an individual technique basis there is overlap with more established and evidence-based psychological techniques. Arguably these could include developing rapport = person-centred counselling; modelling = vicarious learning; eliciting well formed outcomes = goal setting; reframing = cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques; and anchoring = classical conditioning. Inclusion of studies labelled by their authors as NLP and focusing on one of these single NLP techniques would have lead to a misleading observation of the evidence. Publication bias assessment was not formally calculated because only 10 studies were included.18 The scoping reviews around the practice of NLP in physical and mental health conditions suggested it remains a controversial intervention. As only one of the five RCTs showing a positive effect in favour of NLP was found, the authors are less concerned about publication bias. However, it is possible that the controversy surrounding NLP may lead to a publication bias against studies that find a positive effect in favour of NLP.

Risk of bias in the five RCTs was high, or uncertain due to inadequate reporting of methods. It was not possible to determine the risk of bias associated with selective outcome reporting due to the absence of published study protocols. Assessment of the pre-post studies found four scoring lower than the scale midpoint score indicating a high risk of bias.

Implications for research and practice

There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend use of NLP for any individual health outcome. Neither this review, nor the FOI NHS trust data, point strongly to appropriate populations for further research. Use of NLP in specific settings may be vindicated in future, and preliminary data from its use in MRI/claustrophobia may justify a sufficiently powered RCT to clarify its role for these patients. Discussions with NLP key informants identified populations, for example allergy sufferers, who they felt were a strong target population for further NLP-based research. A formal stakeholder consultation with a range of NLP master practitioners would be an important next step for identifying such target populations for research. The strength of evidence for CBT would suggest it as a possible comparison group. The risk of bias assessments point to the need to develop a fully-specified and replicable intervention protocol for evaluation in a sufficiently powered RCT.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many NLP practitioners who, in person and online, helped us develop an understanding of NLP and directed us to possible sources of evidence.

Funding

NHS Coventry commissioned the research and had representation on the steering group. The researchers had independence from the funders in the design and execution of the study. The study was sponsored by University of Warwick who had a research governance role in relation to the study.

Ethical approval

None required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Grindler J, Bandler R. The structure of magic: a book about language and therapy. Oxford: Science and Behaviour; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandler R, Grinder J. Frogs into princes. Moab, UT: Real People Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Association for NLP. Accreditation panel. http://www.anlp.org/accreditation-panel (accessed 8 Oct 2012)

- 4.International NLP Trainers Association. Standards. http://www.inlpta.org/index.php/en/standards-mainmenu-77 (accessed 8 Oct 2012)

- 5.Camana R. Depression: can NLP relieve the sypmptoms of depression? Articlesantch.com http://www.articlesnatch.com/Article/Depression---Can-Nlp-Relieve-The-Sypmptoms-Of-Depression-/1808517#ixzz22U7gGqJj (accessed 3 Aug 2012)

- 6.Russell M. ‘Healer of last resort’ — if you’re caught in the health practitioner round-about. NSW, Australia: Natural Therapy Pages; http://www.naturaltherapypages.com.au/therapist/weightlossadelaide/8722 (accessed 3 Aug 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson G, editor. Magic in practice: introducing medical NLP — the art and science of language in healing and health. London: Hammersmith Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acuity Training and Development. Advanced NLP for doctors. http://www.acuitydr.co.uk/certified-nlp-core-skills-training (accessed 3 Aug 2012)

- 9.Jo Wadell Training. NLP foundation course for doctors. http://www.jowaddell.co.uk/2012-NLP-doctors-course-details.php (accessed 3 Aug 2012)

- 10.Medical NLP. http://medicalnlp.groupsite.com (accessed 8 Oct 12)

- 11.Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1589–1597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alam R, Sturt J, Lall R, Winkley K. An updated meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of psychological interventions delivered by psychological specialists and generalist clinicians on glycaemic control and on psychological status. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, et al. on behalf of the Back Skills Training Trial investigators Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):916–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults. London: NICE; 2009. Clinical guideline 90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heap M. Neurolinguistic programming: an interim verdict. In: Heap M, editor. Hypnosis: current clinical, experimental and forensic practices. London: Croom Helm; 1988. pp. 268–280. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devilly GJ. Power therapies and possible threats to the science of psychology and psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(6):437–445. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J, Green S, editors. The Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ (accessed 3 Aug 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krugman M, Kirsch I, Wickless C, et al. Neuro-linguistic programming treatment for anxiety: magic or myth? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(4):526–530. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Miranda C, de Paula C, Palma D, et al. Impact of the application of neurolinguistic programming to mothers of children enrolled in a day care centre of a shantytown. Sao Paulo Med J. 1999;117(2):63–71. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31801999000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stipancic M, Renner W, Schutz P, Dond R. Effects of neuro-linguistic psychotherapy on psychological difficulties and perceived quality of life. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2010;10(1):39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorensen LB, Greve T, Kreutzer M, et al. Weight maintenance through behaviour modification with a cooking course or neurolinguistic programming. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2011;72(4):181–185. doi: 10.3148/72.4.2011.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson SDR, Dryden W. Comparison between REBT and visual/kinaesthetic dissociation in the treatment of panic disorder: an empirical study. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther. 2011;29(3):158–176. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Einspruch E, Forman B. Neurolinguistic programming in the treatment of phobias. Psychother Priv Pract. 1988;6(1):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timpany L. A study of the effectiveness of single session NLP treatment for pregnancy sickness. 1994 http:/www.transformations.net.nz (accessed 3 Aug 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konefal J, Duncan R. Social anxiety and training in neurolinguistic programming. Psychol Rep. 1998;83(Pt 3):1115–1122. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray R. The Brooklyn programme — innovative approaches to substance abuse treatment. Fed Prob: a Journal of Correctional Philosophy and Practice. 2002:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigley J, Griffiths PD, Prydderch A, et al. Neurolinguistic programming used to reduce the need for anaesthesia in claustrophobic patients undergoing MRI. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(986):113–117. doi: 10.1259/bjr/14421796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dilts R, Delozier J. The encyclopaedia of systemic NLP and NLP new code literature. NLP University Press; http://www.nlpu.com (accessed 3 Aug 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 30.James T, Woodsmall W. Time line therapy and the basis of personality. Capitola, CA: Meta Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]