Abstract

Background

Antidepressant prescribing continues to rise. Contributing factors are increased long-term prescribing and possibly the use of higher selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) doses.

Aim

To review general practice patients prescribed the same antidepressant long-term (≥2 years) and evaluate prescribing and management pre and post-review.

Design and setting

Prospective observational cohort study using routine data from 78 urban general practices, Scotland.

Method

All patients prescribed antidepressants (excluding amitriptyline) for ≥2 years were identified from records November 2009 to March 2010. GPs selected patients for face-to-face review of clinical condition and medication, December 2009 to September 2010. Pre- and post-review data were collected; average antidepressant doses and changes in prescribed daily doses were calculated. Onward referral to support services was recorded.

Results

8.6% (33 312/388 656) of all registered patients were prescribed an antidepressant, 47.1% (15 689) were defined as long-term users and 2849 (18.2%) were reviewed. 811 (28.5%) patients reviewed had a change in antidepressant therapy: 7.0% stopped, 12.8% reduced dose, 5.3% increased dose, and 3.4% changed antidepressant, resulting in 9.5% (95% CI = 9.1% to 9.8% P<0.001) reduction in prescribed daily dose and 8.1% reduction in prescribing costs. 6.3% were referred onwards, half to NHS Mental Health Services. Pre-review SSRI doses were 10–30% higher than previously reported.

Conclusion

Almost half of all people prescribed antidepressants were long-term users. Appropriate reductions in prescribing can be achieved by reviewing patients. Higher SSRI doses may be contributing to current antidepressant growth.

Keywords: antidepressant, drug therapy, depression, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Antidepressant prescribing has increased substantially across Europe and the US since the 1990s.1–4 In Scotland, the majority of antidepressants are prescribed by GPs for the treatment of depression and although prescription volumes have increased by 4.7% in 2008/2009,5 the concurrent incidence and prevalence of depression appears to have remained stable.6,7 The rise in antidepressant prescribing has been mainly explained by small proportional increases of patients receiving long-term treatment,7 alongside reductions in the number of GP consultations for depression: declining by more than half from 2003/2004 to 2008/2009.6,8

Further clarity is needed in understanding the relationship between increased long-term antidepressant prescribing, the reduction in depression consultations and antidepressant prescribing growth. Although current guidelines recommend patients in remission should be reviewed every 6 months to assess the need to continue medication,9,10 there are no formal processes to support general practice review of this patient population and the effect of GPs conducting their own reviews is unknown.

Concern over increasing rates of antidepressant prescribing led the Scottish Government in 2007 to set Health improvement, Efficiency, Governance, Access to services and Treatment (HEAT) targets to reduce prescribing.11In response, the NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHS GG&C) Health Board committed to GPs reviewing long-term antidepressant prescribing in four community health and care partnerships (CHCPs), as medication review demonstrably reduces inappropriate prescribing and costs.12–15 NHS GG&C also knew that six GP practices had higher average prescribed daily doses (PDD) of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) than reported in current literature,4,15–17 therefore PDDs were also of interest as SSRIs account for half of all antidepressant prescriptions.5

The aim of this study was to review general practice patients prescribed the same antidepressant for ≥2 years, and describe prescribing and management pre and post-review.

METHOD

Setting

In 2009, NHS GG&C consisted of 10 local CHCPs which together provide healthcare services for a diverse population of approximately 1.2 million people across a varied geographical area. The review process of patients prescribed long-term antidepressants was rapidly developed by four of the CHCPs serving a highly urbanised population within the most deprived areas of Scotland18 with a high burden of disease and chronic conditions.19 These four CHCPs were interested in reviewing antidepressant prescribing and were high volume prescribers by defined daily doses (DDDs) per capita from the Prescribing and Information System for Scotland (PRISMS). PRISMS is a web-based application providing information for all community dispensed prescriptions and reports at practice, CHCP, health board, and Scotland level.20 DDDs are units of measurement defined by the World Health Organization as ‘the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults’ and does not necessarily reflect the recommended or PDD.21 The use of DDDs enables a convenient method to compare different formulations of medicines and prescribing volumes between different organisations. PRISMS data and General Register Office Scotland22 population statistics were used to calculate DDDs per capita, for the year to September 2009 for CHCP-1, 2, 3, and 4 of 46.2, 43.6, 40.9, and 38.9, respectively. The average DDDs per capita across all 10 CHCPs was 37.6 (range 29.5 to 46.2).

How this fits in

Long-term antidepressant prescribing is increasing and contributing to the overall growth. There are no formal processes to support routine review of this patient population in general practice. Review of people prescribed long-term antidepressants supports optimisation of therapy and reductions in prescribing and associated costs in certain populations.

The four CHCPs recruited practices between November 2009 and March 2010 via an invitation letter to participate from the CHCP prescribing teams and clinical directors. Practices agreed to participate by completing and returning opt-in forms.

Patients

Patients prescribed the same antidepressant for ≥2 years were identified by CHCP support staff using a data extraction tool specifically designed, developed and piloted to identify this patient group from individual General Practice Administration System Scotland (GPASS) systems. GPASS was the most widely used general practice system in NHS GG&C at this time. This tool identified patients prescribed an antidepressant within the previous 3 months and patients prescribed the same antidepressant for 2 years or more. This duration was chosen as current guidelines recommend up to 2 years antidepressant treatment for those at risk of relapse.9,10 Amitriptyline was excluded from the search due to its non-mental health uses.23 Duloxetine was included as an earlier audit of the data found that prescriptions for managing conditions other than depression were sparse.

Patients were excluded if aged <18 years, under regular psychiatric care, had a GP face-to-face antidepressant review within the preceding 6 months, or were on the severe mental illness register (practices review this group as part of the Quality Outcomes Framework [QOF]).

This initiative was primarily intended to support GP review of patients’ clinical condition and medication, in line with current guidelines,9,10 therefore a planned sample size for research purposes was not calculated. However, it was known that patient numbers would be sufficiently high to permit analysis of the prescription data. Practices were asked to review and submit forms for a proportion of all registered patients: equivalent to 30 per 4000 patients. Other than exclusion criteria, GPs were not provided with guidance or a sampling framework from which to select patients, therefore GPs were allowed to prioritise patients for review, permitting flexibility to pragmatically select patients they felt may benefit most, at the expense of introducing selection bias into the study. Reviews took place between December 2009 and September 2010.

At review GPs completed a standardised review form recording: date of review, CHCP, practice, name of antidepressant(s), daily dose, changes in antidepressant therapy and any onward referral. Subsequent amendments were made to capture patients’ age, sex, GP-defined indication, and duration of current antidepressant for CHCP-2 to 4. All practices in the four CHCPs reviewed patients once and CHCP-1 followed-up with a second review within 3 months of the first.

Data handling

Review outcomes were categorised as antidepressant continued, stopped, reduced, increased or changed. Missing outcome data were analysed as though patients had continued with pre-review antidepressant therapy. Where antidepressant names or daily doses were missing it was impossible to ascertain the PDD therefore patients were included in the analysis as antidepressant continued with a PDD of zero milligrams. Where combination antidepressants were prescribed the PDD of each antidepressant was used to calculate the total PDD expressed as DDDs. Onward referrals were categorised as NHS mental health, NHS general medicine, social/council services and non-government organisations. Drug costs from the British National Formulary 59 and Scottish Drug Tariff May 2010 were used for calculations. Data were collated using Microsoft Access® and Excel® and further analysed in SPSS (version 19).

Statistical methods

Statistically significant differences in changes in PDD, expressed as DDD pre and post-review, were analysed using paired two tailed t-test and onward referrals to mental health and non-mental health services by CHCPs using the χ2 test.

RESULTS

Eighty-one per cent (78/96) of practices agreed to participate, representing a total population of 388 656, of whom 8.6% (33 312/388 656) were prescribed an antidepressant, excluding amitriptyline, in the last 3 months and 47.1% (15 689/33 312) were defined as long-term users.

Seven practices dropped out due to practice computer problems, workload issues, and undisclosed reasons. Ninety-one per cent (71/78) of practices agreeing to participate reviewed and submitted forms for 2849 patients, representing 18.2% (2849/15 689) of those prescribed long-term antidepressants: 1.1% (32/2849) were concurrently prescribed two antidepressants and 0.1% (1/2849) prescribed three. No differences were observed between CHCP participating practices (Yates χ2 = 3.27, 18 degrees of freedom [df], P = 0.999), or between participating practices and non-participating practices (Yates χ2 = 7.16, 6 df, P = 0.305). Demographic data were available for 94.4% (2691/2849) patients reviewed and 67.7% (1929/2849) had antidepressant indication recorded (Table 1). Antidepressant dose information was missing for 0.6% (17/2849) of patients.

Table 1.

Review patients’ demographics, antidepressant duration and indication

| Age, years | Mean | ±SD | Median | Range |

| All n = 2691 | 54.4 | 13.4 | 54 | 19–100 |

| Female n = 1975 | 54.8 | 13.7 | 54 | 19–100 |

| Male n = 716 | 53.7 | 12.4 | 53 | 20–87 |

| Duration: same antidepressant (years) | ||||

| All n = 2849a | 5.5 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.0–24.8 |

| Female n = 1975 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.0–24.8 |

| Male n = 716 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 2.0–19.0 |

| Indication for antidepressant n = 1929 | % (n) | |||

| Depression | 65.0% (1253) | |||

| Mixed anxiety depression | 22.1% (426) | |||

| Anxiety disorders | 10.1% (194) | |||

| Otder mental healtd | 1.5% (1.5%) | |||

| General medical | 1.4% (27) | |||

158 patients’ sex not available.

A total of 28.5% (811/2849) patients had a change in antidepressant therapy during their face-to-face review: 7.0% (199/2849) stopped, 12.8% (366/2849) reduced dose, 5.3% (150/2849) increased dose, and 3.4% (96/2849) changed antidepressant altogether. This resulted in a 9.5% (95% CI = 9.1% to 9.8% P <0.001) reduction in mean PDD, expressed as DDDs (Table 2). An estimated 8.1% (£23 320 per annum) reduction in antidepressant prescribing costs were achieved.

Table 2.

Change in prescribed daily doses expressed as defined daily doses (DDDs)

| Pre-review | Post-review | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHCP | Number of patients | Number of ADMs prescribed | Total % PDDa | Mean PDDa (SD) | Total PDDa | Mean PDDa (SD) | Total PDDa change | 95% CI % PDDa change | P-valueb |

| CHCP-1 | 599 | 618 | 872.2 | 1.46 (0.83) | 792.7 | 1.32 (0.89) | ↓ 9.3% | 8.6 to 10.1 | 0.007 |

| CHCP-2 | 485 | 492 | 668.8 | 1.38 (0.73) | 629.7 | 1.30 (0.80) | ↓ 5.9% | 5.2 to 6.6 | 0.101 |

| CHCP-3 | 1039 | 1041 | 1333.8 | 1.28 (0.63) | 1203.8 | 1.16 (0.70) | ↓ 9.7% | 9.2 to 10.3 | <0.001 |

| CHCP-4 | 726 | 732 | 901.7 | 1.24 (0.67) | 793.8 | 1.09 (0.73) | ↓ 12.0% | 11.2 to 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Total | 2849 | 2883 | 3776.5 | 1.33 (0.71) | 3419.9 | 1.20 (0.77) | ↓ 9.5% | 9.1 to 9.8 | <0.001 |

| cCHCP-1 Review 2 | 525d | 525 | 696.0 | 1.38 (0.85) | 653.6 | 1.29 (0.89) | ↓ 6.1% | 5.9 to 7.1 | 0.006 |

PDD expressed DDDs.

95% CI calculated using a two tailed t-test.

CHCP-1: GPs performed two reviews, therefore second review shown separately.

Of the 525 patients attending second review: 485 were prescribed one antidepressant, 20 prescribed two antidepressants and 20 prescribed none. ADMs = antidepressant medicines. DDD = defined daily dose. PDD = prescribed daily dose. SD = standard deviation.

There was significant variation between CHCPs in patients continuing, stopping, reducing, increasing, or changing antidepressants (χ2 = 30.89, 12 df, P <0.005). This was attributable to CHCP-1 having fewer patients change antidepressant than CHCPs 2, 3 & 4. There was no significant difference between CHCPs 2, 3 and 4.

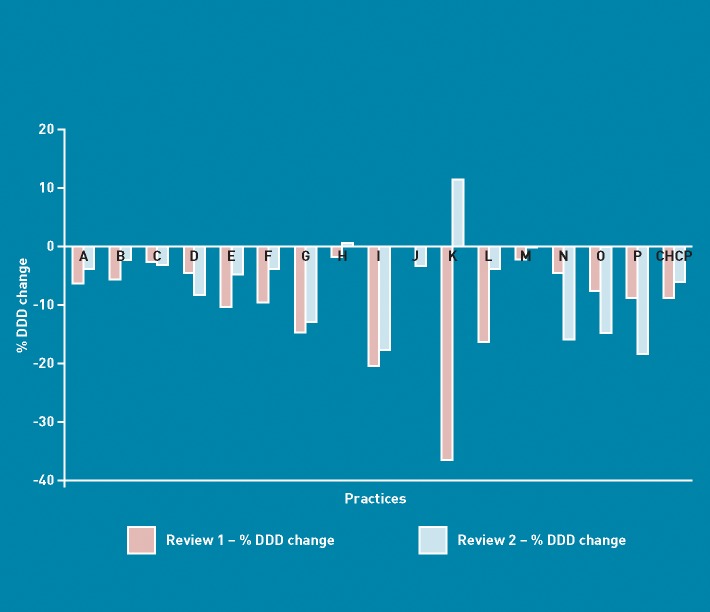

In CHCP-1 87.6% (525/599) patients had a second review (Figure 1). This resulted in a further 6.1% (95% CI = 5.9% to 7.1%, P = 0.006) reduction in PDD and an estimated 6.8% (£4346 per annum) reduction in prescribing costs. Of the 38 patients who stopped their antidepressant during the first review nine (24%) restarted, 22 (58%) did not restart and 7 (18%), were lost to follow-up. Of the 87 patients who reduced dose, 11 (13%) stopped, 34 (39%) continued on lower dose, 13 (15%) had a further reduction, 11 (13%) increased, 1 (1%) changed, and 17 (19%) were lost to follow-up.

Figure 1.

CHCP-1 % change in prescribed daily dose (expressed as defined daily dose) pre- to post-review.

A total of 6.3% (179/ 2849) patients were referred onwards to support services: 50.5% NHS mental health, 23.1% non-government organisations, 14.5% NHS general medical and 11.8% social and council services. Results were aggregated into NHS mental health versus non-mental health services (Table 3), finding significant inter-CHCP variation (χ2 = 10.4, 3 df, P <0.015) with CHCP-2 having more referrals to non-mental health services. There was no significant difference between the other CHCPs. In comparison to all the other practices, practice K reviewed a patient group with higher than average SSRI doses and appears to have a different pattern of change in PDD at review 1 to review 2. More data is required to comment further.

Table 3.

Onward referral to support services

| CHCP-1 | CHCP-2a | CHCP-3a | CHCP-4 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient reviews resulting in onward referral, n (%) | 27 (4.5) | 43 (8.9) | 66 (6.3) | 43 (5.9) | 179 (6.3) |

| Referrals to services, n (%) | |||||

| NHS mental health services | 19 (67.8) | 15 (31.9) | 37 (54.4) | 23 (53.5) | 94 (50.5) |

| Non-mental health services | 9 (32.1) | 32 (68.1) | 31 (45.6) | 20 (46.5) | 92 (49.5) |

Some patients were referred to more than one support service. Mental health services included: community mental health teams, primary care mental health teams and community addictions teams. Non-mental health services included: NHS general medical clinics (pain, cardiovascular, diabetic, etc), social and council services (social services, housing association, Live Active exercise etc) and non-government organisations (Citizens Advice, Glasgow Council on Alcohol, Life Link etc).

A total of 2883 antidepressants where prescribed for the 2849 patients. Pre-review mean PDDs were calculated for each antidepressant (Table 4). For patients with a recorded indication of depression or mixed anxiety depression, pre-review mean (±SD) antidepressant PDDs were 26.3 mg (±10.2 mg) and 27.0 mg (±12.5 mg) for citalopram and fluoxetine, respectively. Evidence is lacking for improved citalopram or fluoxetine efficacy at doses greater than 20 mg daily for the treatment of depression.24,25

Table 4.

Pre-review mean antidepressant prescribed daily dose and defined daily dose equivalent

| ADMs prescribed, n (%) (N = 2883) | Mean dose (SD) (mg) | Range, mg | Median, mg | Mean PDD as DDD | Mean PDD as DDD (SD) from literature4,14–16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine | 773 (26.8) | 28.7 (13.0) | 10–60 | 20 | 1.43 (0.65) | 1.05 [Poluzzi et al 20044] 1.07 [Donoghue et al 199614] 1.08 [Truter & Kotze16] |

| Citalopram | 744 (25.8) | 28.2 (13.8) | 4.3–60 | 20 | 1.41 (0.69) | 1.17 [McManus et al 200315] 1.3 [Poluzzi et al 20044] 1.2 [Truter & Kotze16] |

| Paroxetine | 250 (8.7) | 26.2 (10.5) | 5–60 | 20 | 1.31 (0.52) | 0.90 [Poluzzi et al 20044] 1.13 [Donoghue et al 199614] 1.15 [McManus et al 200315] 1.05 [Truter & Kotze16] |

| Venlafaxine | 210 (7.3) | 139.6 (72.2) | 18.75–375 | 150 | 1.40 (0.72) | 1.22 [McManus et al 200315] |

| Trazodone | 194 (6.7) | 171.3 (105.0) | 50–600 | 150 | 0.57 (0.35) | 0.30 [Poluzzi et al 20044] |

| Sertraline | 178 (6.2) | 94.4 (41.3) | 25–200 | 100 | 1.89 (0.83) | 0.90 [Poluzzi et al 20044] 1.60 [Donoghue et al 199614] 1.45 [McManus et al 200315] |

| Mirtazapine | 175 (6.1) | 35.5 (10.5) | 15–60 | 30 | 1.18 (0.35) | 1.25 [Poluzzi et al 20044] |

| Dosulepin | 145 (5.0) | 103.3 (49.0) | 25–225 | 75 | 0.69 (0.33) | 0.51 [Donoghue et al 199614] 0.55 [McManus et al 200315] |

| Escitalopram | 70 (2.4) | 15.4 (6.5) | 5–40 | 20 | 1.54 (0.65) | |

| Lofepramine | 61 (2.1) | 141.2 (53.9) | 70–280 | 140 | 1.34 (0.51) | 1.28 [Donoghue et al 199614] |

| Duloxetine | 33 (1.1) | 65.6 (29.0) | 30–120 | 60 | 1.09 (0.48) | |

| Other | 50 (1.7) | |||||

ADMs = antidepressant medicines. DDD = defined daily doses. PDD = prescribed daily dose. SD = standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Almost half of all study patients prescribed antidepressants were prescribed the same antidepressant long-term. Reviewing long-term patients resulted in one in four having their antidepressant therapy altered, providing reductions in prescribing and possible associated costs. Where follow-up reviews were performed, further additional reductions were made.

About 6% of patients were referred onwards to support services, with half to non-mental health services. There was significant variation between CHCPs for the type of service category referral, likely influenced by geographical location of services and service availability.

The pre-review average PDDs of the majority of antidepressants are higher than previously reported in literature,4,15–17 with SSRI doses 10–30% higher.

Strengths and limitations

This is possibly the largest study reported using routine primary patient data to quantify changes in antidepressant prescribing and management and has an advantage over other studies by linking patient, antidepressant, PDD, indication,and duration of named antidepressant, thereby overcoming some limitations identified in other studies.4,7,26,27

Medication review has been shown to be effective at reducing prescribing quantities and costs in general practice.11–14 The magnitude of observed change in PDDs, expressed as DDDs, vary with: antidepressant, individual patient, and groups of patients reviewed, which is also true for observed prescribing costs changes that are influenced by the use of proprietary medicines, drug tariff prices and patent expiry. Although this study was set in highly urbanised and deprived areas which may have increased the magnitude of observed DDD change, the study believes the review process itself could be generalised to other settings. A more robust health economic evaluation would have been beneficial here in determining whether cost savings from reduced prescriptions were offset by GP time in undertaking face-to-face reviews.

The follow-up reviews by CHCP-1 demonstrated further prescribing reductions could be made. However, the 3-month time period is likely too short to assess sustainability of reductions, especially as common mental health problems are relapsing and remitting in nature.9,10 Therefore, a 12-fmonth follow-up period with reviews at 3, 6, and 12 months would be more appropriate to assess long-term sustainability of prescribing changes.28 Being a quasi-experimental study, the inclusion of a control group or any randomisation mechanism was not possible and as GPs prioritised which patients were reviewed, a positive selection bias was likely introduced toward larger PDD reductions. In an ideal experimental study the study would have developed a randomised sampling framework of patients on long-term antidepressant medications for review. Further, the study cannot rule out the possibility that reductions observed were a result of the statistical phenomenon of regression to the mean, however study patients were a stable population of long-term users and not predicted to get better over time, with or without an antidepressant.

Positive identification of patients’ prescribed long-term antidepressants helped GPs engage with the review process and accommodate the increased workload within usual practice constraints. As GPs pragmatically selected a sample of patients prescribed long-term antidepressants for review, it is not possible to confidently infer generalisability of results to other patient populations, although it is feasible that GPs elsewhere may adopt similar criteria for patient selection. Using PRISMS it is difficult to predict wholesale CHCP level prescribing changes as a 9.5% reduction in PDDs, expressed as DDDs, equates to <1.0% reduction in total CHCP DDDs for 33 312 patients prescribed antidepressants.

This study established variations in antidepressant mean doses by CHCP geographical location, which was not possible in a previous study.26 As average CHCP PDDs follow a similar trend to CHCP DDDs per capita, this indicates that regional and practice average PDD contribute to the variations in antidepressant prescribing along with practice and practitioner factors.26,29 This study is limited to 4 CHCPs which constrains further assessment of this observation.

Comparison with existing literature

This study found that 8.6% of registered patients were prescribed an antidepressant: higher than previously reported in a UK study of 6.9% (5648/81 221)30 and lower than estimated by NHS Scotland Information Services Division 10.4%.5 The 47.1% of patients prescribed long-term antidepressants is comparable with other studies of 48%30 and 40.6–51.4%,7 however the mean PDD of SSRIs are substantially higher than previously reported,4,15–17 suggesting a tendency to ‘push the dose’ in these CHCPs.

The proportion of patients referred to non-pharmacological services is relatively small. As long-term antidepressant users are more ‘expert’ in managing their condition, conceivably they can make better informed choices about personal management strategies, be they pharmacological, non-pharmacological or non-medicalised.31,32

Implications for practice and research

The challenge for clinical practice is that increasing numbers of people are being prescribed antidepressants long-term,7 in spite of consultations for depression appearing to reduce8 and frequency of antidepressant review reducing with therapy duration.33 Use of long-term antidepressants for some patients may be appropriate to minimise relapse.27,34 Although fewer reviews may be appropriate for some ‘expert’ patients31 this is inappropriate for others, such as older people with increased risk of adverse effects.35 Reviewing continued antidepressant therapy provides an opportunity to optimise pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, and address repeat prescribing issues.36,37 The current QOF 2011/2012 supports the identification and initial management of people with depression38 but not their continued care. Future structures, as previously called for,39 should consider proactive management of depression as part of long-term condition management strategies.

SSRIs demonstrate a flat dose response curve for the treatment of depression,9,10,24,25 meaning prescribing doses >20 mg daily citalopram/fluoxetine/paroxetine or 50 mg daily sertraline is not supported by current evidence to provide better efficacy.9,10,24,25 Historically GPs prescribed subtherapeutic doses of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)14,15,27 and over the years campaigns40 and guidelines9,10,41 have supported a message to prescribers to increase antidepressant doses to achieve better patient response and remission of depressive symptoms. This message is appropriate for TCAs and venlafaxine whose efficacy increases as dose increases,9,10,24,25 but not for SSRIs where it may be more efficacious to change compliant non- and poor-SSRI responders to a different SSRI rather than increasing the dose.

As increasingly more antidepressants are prescribed long-term, more retrospective and prospective routine data studies are required to assess antidepressant long-term safety and efficacy. Further opportunities exploiting routine data exist in assessing impact of local and national prescribing targets, policies and guidelines in analyses of linked individual patient level prescriptions, PDDs and e-health diagnoses data. Lastly, qualitative research approaches have a role in explaining why GPs may ‘push the dose’.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to all patients, GP practices, prescribing support teams, CHCP and NHS GG&C mental health partnership staff for their work and support. Richard Hassett for designing, developing and piloting the data extraction tool. Andrew Morgan for developing the database.

Funding

The initiative was incentivised with CHCP Local Enhanced Service and NHS GG&C Mental Health Collaborative monies. This work is independent of the funder and does not necessarily represent their view.

Ethical approval

This service evaluation study was primarily undertaken to support practices to optimise normal patient care as per current mental health guidelines and work towards addressing the antidepressant HEAT targets. GPs chose which patients to review and how to optimise care in line with current local and national guidelines. The NRES guidelines indicate for this project no IRB approval was necessary.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Middleton N, Gunnell D, Whitley E, et al. Secular trends in antidepressant prescribing in the UK, 1975–1998. J Public Health Med. 2001;23(4):262–267. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.4.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental health policy and practice across Europe: the future direction of mental health care. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill, Open University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Kelton CM, Jing Y, et al. Utilization, price, and spending trends for antidepressants in the US Medicaid Program. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4(3):244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poluzzi E, Motola D, Silvani C, et al. Prescriptions of antidepressants in primary care in Italy: pattern of use after admission of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for reimbursement. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;59(11):825–831. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0692-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Information Services Division, Scotland. Antidepressants. Edinburgh: ISD Scotland; 2011. http://www.isdscotlandarchive.scot.nhs.uk/isd/information-and-statistics.jsp?pContentID=3671&p_applic=CCC&p_service=Content.show& (accessed 19 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munoz-Arroyo R, Sutton M, Morrison J. Exploring potential explanations for the increase in antidepressant prescribing in Scotland using secondary analyses of routine data. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(527):423–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore M, Yuen H, Dunn N, et al. Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: A descriptive study using the general practice research database. BMJ. 2009;339(7727):956–961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Information Services Division, Scotland. General practice depression consultations. Edinburgh: ISD; 2011. http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/3711.html (accessed 19 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression in adults (update). Clinical Guideline CG90. London: NICE; 2009. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG90/ (accessed 19 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson IM, Ferrier IN, Baldwin RC, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(4):343–396. doi: 10.1177/0269881107088441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Scottish Government. Depression Workstream Overview. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/01/18120533/3 (accessed 8 Oct 2012)

- 12.Mackie CA, Lawson DH, Campbell A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of medication review in patients receiving polypharmacy in a general practice setting. Pharm J. 1999;263:R7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zermansky AG, Petty DR, Raynor DK, et al. Randomised controlled trial of clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients receiving repeat prescriptions in general practice. BMJ. 2001;323(7325):1340–1343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7325.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson C, Thomson A. Prescribing support pharmacists support appropriate benzodiazepine and Z-drug reduction 2008/09 — experiences from North Glasgow. Clin Pharm. 2010;3(Suppl 1):S5–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donoghue J, Tylee A, Wildgust H. Cross sectional database analysis of antidepressant prescribing in general practice in the United Kingdom, 1993–5. BMJ. 1996;313(7061):861–862. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7061.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McManus P, Mant A, Mitchell P, et al. Use of antidepressants by general practitioners and psychiatrists in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37(2):184–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truter I, Kotze TJ. An investigation into the prescribing patterns of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in South Africa. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1996;21(4):237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1996.tb01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scottish Government. Scottish index of multiple deprivation: 2009 general report. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2010. August http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2009/10/28104046/0 (accessed 19 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scottish Government, Inequalities in health. Report of the Measuring Inequalities in Health Working Group. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; November 2003. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/47171/0013513.pdf (accessed 19 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prescribing and Information System for Scotland (PRISMS) http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Prescribing-and-Medicines/PRISMS/ (accessed 8 Oct 2012)

- 21.World Health Organization. Definitions and general considerations. Geneva: WHO; 2009. http://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/ (accessed 19 Sep 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.General Register Office Scotland. http:www.gro-scotland.gov.uk (accessed 19 Sep 2012)

- 23.British National Formulary 58. London: BMA and Royal Pharmaceutical Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adli M, Baethge C, Heinz A, et al. Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):387–400. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corruble E, Guelfi JD. Does increasing dose improve efficacy in patients with poor antidepressant response: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(5):343–348. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101005343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison J, Anderson MJ, Sutton M, et al. Factors influencing variation in prescribing of antidepressants by general practices in Scotland. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(559):e25–31. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X395076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donoghue JM, Tylee A. The treatment of depression: prescribing patterns of antidepressants in primary care in the UK. Br J Psych. 1996;168(2):164–168. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams N, Simpson AN, Simpson K, Nahas Z. Relapse rates with long-term antidepressant drug therapy: a meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2009;24(5):401–408. doi: 10.1002/hup.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hull SA, Aquino P, Cotter S. Explaining variation in antidepressant prescribing rates in east London: a cross sectional study. Fam Pract 2005. 2005;22(1):37–42. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petty DR, House A, Knapp P, et al. Prevalence, duration and indications for prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. Age Ageing. 2006;35(5):523–526. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schofield P, Crosland A, Waheed W, et al. Patients’ views of antidepressants: from first experiences to becoming expert. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(585):142–148. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X567045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornford CS, Hill A, Reilly J. How patients with depressive symptoms view their condition: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):358–364. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middleton DJ, Cameron IM, Reid IC. Continuity and monitoring of antidepressant therapy in a primary care setting. Qual Prim Care. 2011;19(2):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361(9358):653–661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, et al. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zermansky AG. Who controls repeats? Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(412):643–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saastamoinen LK, Enlund H, Klaukka TJ. Repeat prescribing process in primary care: a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2008;16(3):155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for GMS contract 2011/12. Delivering investment in general practice. London: BMA NHS Employers; April 2011. http://www.nhsemployers.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/QOFguidanceGMScontract_2011_12_FL%2013042011.pdf (accessed 19 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews G. Should depression be managed as a chronic disease? BMJ. 2001;322(7283):419–421. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rix S, Paykel ES, Lelliott P, et al. Impact of a national campaign on GP education: an evaluation of the Defeat Depression Campaign. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(439):99–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paykel ES, Freeling P. Treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 1992;304(6838):1380–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6838.1380-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]