Summary

To prevent re-replication of DNA in a single cell cycle, the licensing of replication origins by Mcm2-7 is prevented during S and G2 phases. Animal cells achieve this by cell cycle regulated proteolysis of the essential licensing factor Cdt1 and inhibition of Cdt1 by geminin. Here we investigate the consequences of ablating geminin in synchronised human U2OS cells. Following geminin loss, cells complete an apparently normal S phase, but a proportion arrest at the G2/M boundary. When Cdt1 accumulates in these cells, DNA re-replicates, suggesting that the key role of geminin is to prevent re-licensing in G2. If cell cycle checkpoints are inhibited in cells lacking geminin, cells progress through mitosis and less re-replication occurs. Checkpoint kinases thereby amplify re-replication into an all-or-nothing response by delaying geminin-depleted cells in G2. Deep DNA sequencing revealed no preferential re-replication of specific genomic regions after geminin depletion. This is consistent with the observation that cells in G2 have lost their replication timing information. In contrast, when Cdt1 is overexpressed or is stabilised by the Neddylation inhibitor MLN4924, re-replication can occur throughout S phase.

Keywords: Geminin, DNA replication, replication licensing, re-replication, deep sequencing

Introduction

The precise replication of chromosomal DNA during S phase of the cell cycle is crucial for genetic integrity to be maintained. To prevent any segment of DNA replicating more than once in a single cell cycle, replication is divided into two non-overlapping steps (Blow and Dutta, 2005; Arias and Walter, 2007). In the first stage, which occurs in late mitosis and early G1 phase, origins of replication are “licensed” by being loaded with Mcm2-7 complexes. When replication origins initiate during S phase, DNA-bound Mcm2-7 complexes are activated as DNA helicases to drive assembly and progression of replication forks. In order to prevent the re-replication of DNA, no further origin licensing (Mcm2-7 reloading) can occur once a cell enters S phase. Defects in the correct regulation of the replication licensing system may be an important cause of the genetic instability commonly seen in cancer cells (Blow and Gillespie, 2008).

Origin licensing involves the stepwise assembly of ‘pre-Replicative Complex’ (pre-RC) proteins onto DNA, and has been reconstituted in vitro with pre-RC proteins from Xenopus eggs (Gillespie et al., 2001) and budding yeast (Evrin et al., 2009; Remus et al., 2009). ORC, the origin recognition complex, first binds DNA, then recruits Cdc6 and Cdt1. These proteins then act together to load Mcm2-7 onto DNA. This reaction probably involves the opening of the Mcm2-7 hexameric ring and clamping it around DNA (Evrin et al., 2009; Remus et al., 2009). Mcm2-7 complexes are loaded onto origins as double hexamers, providing a configuration capable of initiating a pair of bidirectional replication forks (Evrin et al., 2009; Remus et al., 2009; Gambus et al., 2011).

A number of different mechanisms have been described that block licensing in S and G2 phases (Blow and Dutta, 2005; Arias and Walter, 2007). In yeasts, CDKs, which are active from late G1 until the end of mitosis, negatively regulate different pre-RC proteins. In metazoans, additional mechanisms that are only indirectly dependent on CDK activity play the major role (Blow and Dutta, 2005; Arias and Walter, 2007). In all metazoans studied to date, down-regulation of Cdt1 activity is the major route by which origin licensing is prevented in S phase and G2. This is achieved by a combination of cell-cycle-regulated proteolysis and inhibition by a small protein, geminin.

Cdt1 proteolysis is driven by polyubiquitylation. The SCF-Skp2 ubiquitin ligase ubiquitylates Cdt1 during S phase and G2 and is dependent on CDK-dependent phosphorylation of Cdt1 (Li et al., 2003; Sugimoto et al., 2004; Nishitani et al., 2006). In addition, a DDB1 and CUL4-dependent ubiquitin ligase is activated for Cdt1 ubiquitylation by its interaction with PCNA, which occurs either during S phase or in response to DNA damage (Zhong et al., 2003; Arias and Walter, 2006; Nishitani et al., 2006; Senga et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2010).

Cdt1 is also inhibited by binding to geminin, which is active throughout S phase, G2 and early mitosis (McGarry and Kirschner, 1998; Tada et al., 2001; Wohlschlegel et al., 2000). At the end of mitosis, geminin is polyubiquitinated by the Anaphase Promoting Complex. Polyubiquitylation targets geminin for proteasome-mediated degradation (McGarry and Kirschner, 1998) or inactivation (Hodgson et al., 2002; Li and Blow, 2004; Yang et al., 2011; Kisielewska and Blow, 2012), allowing the licensing system to be activated. The mechanism by which geminin inhibits Cdt1 is currently unclear but may involve formation of an inhibitory 2:4 Cdt1:geminin complex (Lutzmann et al., 2006; De Marco et al., 2009). Removal of geminin from somatic cells typically results in extensive re-replication, which in turn activates DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoint kinases (Melixetian et al., 2004; Mihaylov et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2004).

In the present work we have investigated in detail the consequences of an acute loss of geminin in human U2OS cells. We show that following geminin loss, most cells complete an apparently normal S phase, but a proportion undergo cell cycle arrest at the G2/M boundary. As Cdt1 levels build up in these cells, they eventually start to re-replicate their DNA. We show that cell cycle checkpoints thereby enhance the amount of re-replication, by amplifying it into an all-or-nothing response.

Results

Transient geminin depletion is lethal

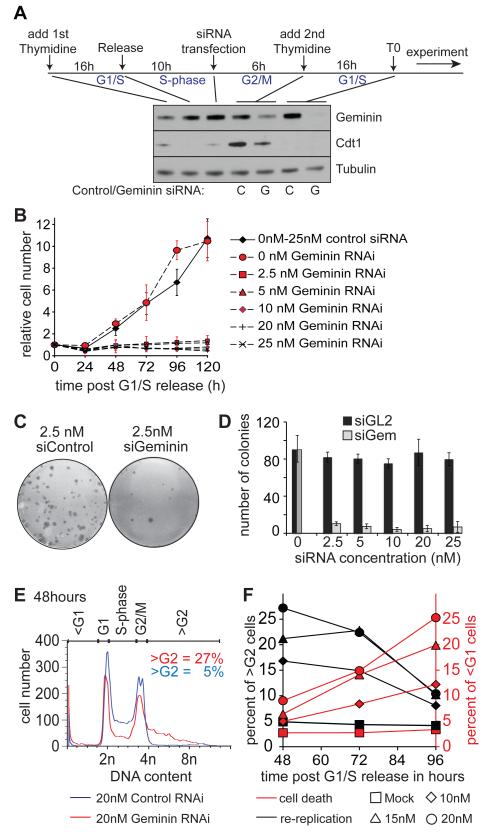

We first developed an RNAi knockdown protocol where essentially normal cells progress into S phase in the absence of geminin. Asynchronous cultures of U2OS human osteosarcoma cells were released from an initial thymidine block, transfected with RNAi and then synchronised again in early S phase with thymidine (Fig 1A). After release from this second thymidine block, a time we designate as ‘T0’, cells progress synchronously through S phase in the absence of geminin. Even very low levels of geminin siRNA (2.5 nM) severely inhibited subsequent cell proliferation (Figure 1B). Clonogenic assays showed that as little as 2.5 nM geminin siRNA decreased colony numbers to near background levels (Figure 1C, 1D).

Figure 1. Geminin depletion causes inhibition of proliferation and re-replication accompanied by cell death.

A. Schematic for double thymidine synchronisation and RNAi transfection. At the indicated stages, whole cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotted for geminin, Cdt1 and tubulin. ‘C’: cells treated with control siRNA. ‘G’: cells treated with geminin siRNA. B. Cell number at various times after transfection with different concentrations of control or geminin RNAi. C. Example well of clonogenic assays for cells treated with 2.5 nM control or geminin siRNA. D. Clonogenic assay of cells treated with increasing amounts of geminin or control RNAi. The graph shows the results of two biological experiments in triplicates, with standard error. E. DNA content of cells treated with 20 nM geminin or control siRNA 48 h after release from double thymidine block. F. Titration of geminin siRNA at different time points after release from thymidine block; cultures were subject to flow cytometry, and the percentage of cells with <G1 or >G2 DNA content is shown.

In agreement with previous studies (Melixetian et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004) we observed by flow cytometry that geminin RNAi induced substantial levels of re-replication, with typically 20 - 35% of cells exhibiting a >4C DNA content 48 h after thymidine release (Figure 1E). At longer times, the number of re-replicated cells (>4C DNA content) decreased with an associated increase in cell death (<2C DNA content) (Fig 1F). These results suggest that re-replication induced by a lack of geminin ultimately results in apoptosis in U2OS cells, as is seen in other cancer cell lines (Zhu et al., 2004; Zhu and DePamphilis, 2009). Consistent with this idea, when cells with >4C DNA content were plated out they were unable to form colonies (Supplementary Figure S1 and data not shown).

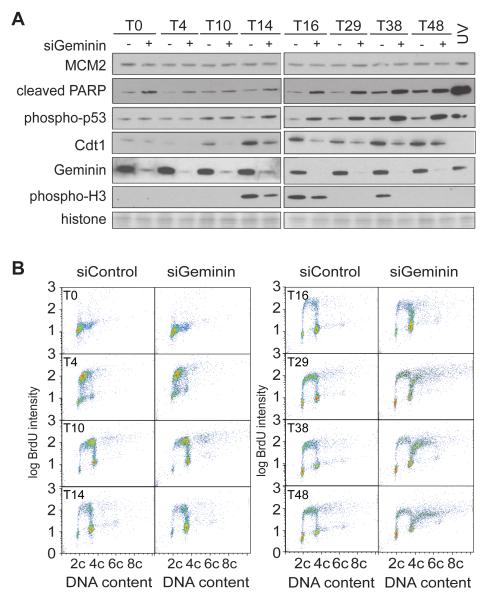

We next investigated possible molecular mechanisms leading to cell death in geminin-depleted cells. Immunoblotting of cell extracts showed that cleaved PARP and phospho-p53 became significantly increased in geminin depleted cells 48 h after thymidine release (Figure 2A). At 120 h we detected a drop in cells with >4C DNA content accompanied by a strong increase in cell death and appearance of phospho-H2AX, which is likely due to fragmentation of the genome during apoptosis (Supplementary Figure S2). This data suggests that cell death is an inevitable consequence of re-replication in U2OS cells.

Figure 2. Flow cytometry of cells re-replicating after geminin depletion.

Cells were released from a double thymidine block after prior treatment with either control or geminin RNAi, as in Figure 1A. A. Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts at different times after thymidine release. Geminin RNAi: +; control RNAi: −. As control, cells were treated with 120 mJ UV 4h after thymidine release. The membrane was also stained with amido black to show equal loading of histones. B. At different times after release from double thymidine block, cells were pulsed with BrdU and analysed by flow cytometry.

Geminin depletion does not significantly alter S-phase progression

Figure 2B shows flow cytometry of cells pulse-labelled with BrdU at different times after release from thymidine in the presence or absence of geminin. During the first 10 h of S phase there was no significant difference in BrdU intensity or DNA content between control and geminin depleted cells. By 14-16 h about 50-60% of control cells were BrdU negative and had a G2/M DNA content. Many of these cells were passing through mitosis, as indicated by phospho-H3 staining (Figure 2A). Whilst the majority of geminin-depleted cells at 14-16 h also had a near-G2/M DNA content (Figure 2B), a significant proportion remained BrdU positive. This was associated with a reduced staining for phospho-H3 and an increase in phospho-p53 and cleaved PARP (Figure 2A). At later times, control cells were again seen in G1 and S phase, while geminin-depleted cells were either enriched at G2/M or had a >4C DNA content.

These results indicate that geminin depletion does not significantly alter initial progress through S-phase. The very low levels of Cdt1 present during S phase (Figure 2A) may limit re-licensing in the absence of geminin. However, geminin-depleted cells show a defect in progression into mitosis, associated with continued BrdU incorporation and checkpoint activation, which is potentially a result of a small number of origins re-firing. In G2 and mitosis, Cdt1 levels start to rise again, though this was lower in the geminin-depleted cells than in control cells. The lower Cdt1 levels are likely a consequence of Cdt1 proteolysis (Ballabeni et al., 2004), which possibly occurs as a consequence of re-replication-induced DNA damage (Hall et al., 2008). Without geminin to restrain Cdt1 activity in cells held at the G2/M border, MCM2-7 can be loaded onto DNA and induce massive re-replication.

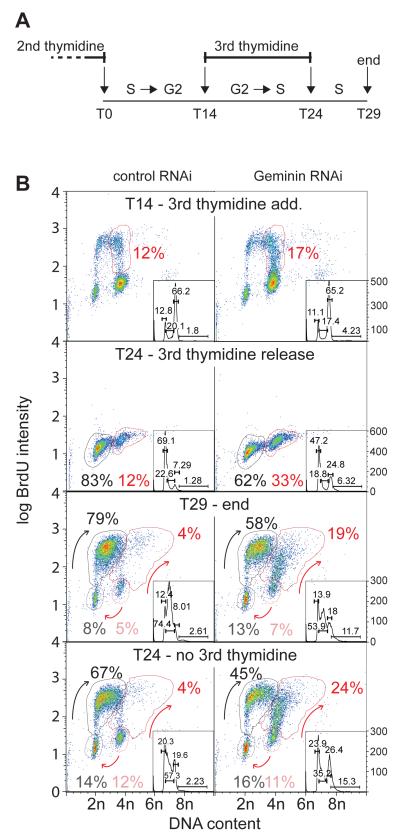

Re-replication occurs from late S-phase and G2

We therefore tested whether the majority of geminin-depleted cells undergo re-replication only once they have finished the bulk of first round DNA synthesis. Fourteen hours after the second thymidine release, when both control and geminin-depleted cells were mainly in G2/M, thymidine was again added for 10 h, allowing cells that had completed S phase to progress through mitosis and G1 but preventing further DNA replication or re-replication (Figure 3). At this stage (T24), 83% of cells in the control sample progressed through mitosis and G1 and accumulated in early S-phase, while the 12% that were in late S-phase at the time of thymidine addition arrested in late S-phase. Most of these cells started incorporating BrdU after release from the 3rd thymidine block (T29 control cells). In the geminin depleted sample at T24, only 62% cells had progressed through mitosis and G1, while 33% remained with an ~4C DNA content. Since only 17% of cells were actively incorporating BrdU at the time of the third thymidine addition (T14), this suggests that a significant proportion of the geminin-depleted cells were prevented from entering mitosis even though they were not incorporating significant amounts of BrdU. After geminin-depleted cells had been released from this third thymidine block for 5 h (T29), almost two thirds of the cells that had arrested in G2 (19% of the total) started to re-replicate. This third thymidine arrest only slightly reduced the number of geminin-depleted cells undergoing re-replication (T24, no 3rd thymidine). These results suggest that geminin depletion causes a subset of cells to linger in a late S/G2 phase state without progressing into mitosis, and that these cells subsequently start to re-replicate their DNA.

Figure 3. Re-replication induced from G2 by 3rd thymidine block.

Cells were released from a double thymidine block after prior treatment with either control or geminin RNAi, as in Figure 1A. 14 hr later cells were optionally given a 3rd thymidine block for 10 hr, and then released for a further 5 h. A. Schematic of experiment. B. At different times during the procedure, batches of cells were given a BrdU pulse and then analysed by flow cytometry. Arrows show the movement of cells suggested by the data.

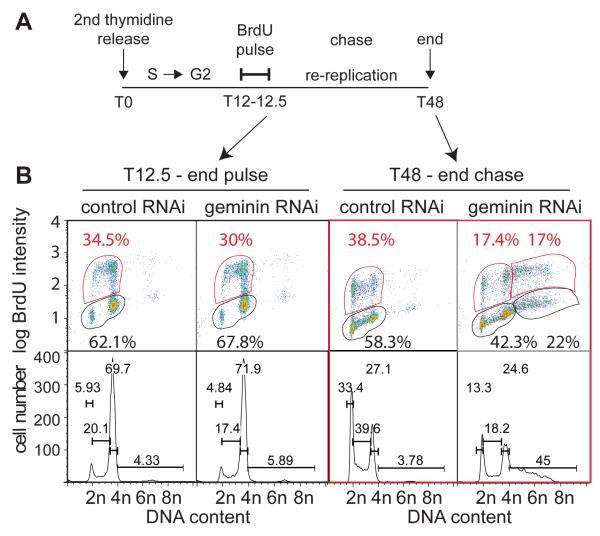

In order to demonstrate that re-replication occurs in G2 cells that had effectively ceased DNA synthesis, we carried out a pulse chase experiment, where cells at 12 h after the second thymidine release (T12) were pulse labeled with BrdU for 30 min (Figure 4A). At this time the majority of cells had progressed through S-phase and were BrdU negative (Figure 4B). The BrdU was then removed and the cells chased for 36 h to allow time for re-replication to occur. After the chase, more than half of the cells with a >4C DNA content (22% of total cells, where 39% were >4C DNA) were BrdU negative. This shows that cells in G2 can subsequently start to re-replicate.

Figure 4. Assessment of cells spontaneously re-replicating from G2.

Cells were released from a double thymidine block after prior treatment with either control or geminin RNAi, as in Figure 1A. 12 hr later cells were pulsed with BrdU for 30 mins. BrdU was then removed and cultures continued for a further 35.5 h. A. Schematic of experiment. B. At different times during the procedure, batches of cells were analysed by flow cytometry.

The G2/M checkpoint promotes re-replication of geminin depleted cells

Several studies have shown that re-replication activates the G2/M checkpoint and prevents progression into mitosis (Melixetian et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004). However, the resynthesis of Cdt1 that occurs once S phase has finished may make cells uniquely dependent on geminin to restrain re-licensing of replicated DNA during G2. Because our results suggest that it is G2-arrested cells that predominantly undergo re-replication, we investigated whether G2 checkpoint activity actually enhances re-replication in geminin-depleted cells. We used our synchronized re-replication assay to address this question by treating cells with checkpoint inhibitors 12 – 18 h after release from the thymidine block, during the time when geminin-depleted cells accumulate in G2 (Figure 5A). This allows geminin-depleted cells to pass through mitosis and re-enter G1. Caffeine was withdrawn at 18 h and the incubation continued for a further 9 hr to allow cells to pass through S phase. After this time (27 h) cells were labelled with BrdU and analysed by flow cytometry. Treatment of geminin-depleted cells with caffeine significantly reduced both the number of cells arrested in G2 and the number of cells with >G2 DNA content (Fig 5B, D). Similar results were observed when Chk1 was inhibited by UCN-01 (Fig 5C, D). In contrast, treatment with the ATM inhibitor KU55933 or co-depletion of p53 showed no or very little impact on the levels of re-replication (Fig 5D, E). Taken together with Figures 3 and 4, we draw two conclusions from these results. First, ATR and Chk1, but not ATM, are the major checkpoint kinases responsible for the G2/M arrest of geminin depleted cells. Second, ATR and Chk1 actually promote DNA re-replication in geminin-depleted cells by delaying them in G2, a cell cycle stage where they are particularly dependent on geminin for preventing re-licensing of replicated DNA. This potentially amplifies the effect of a small amount of re-replication, creating an ‘all or nothing’ effect (see Discussion).

Figure 5. The G2/M checkpoint promotes re-replication.

Cells were released from a double thymidine block after prior treatment with either control or geminin RNAi, and optionally p53 RNAi, as in Figure 1A. 12 h after release, cells were optionally treated with caffeine, UCN-01 or KU55933 for 6 h. 27 h after thymidine release, cells were pulsed with BrdU and analysed by flow cytometry. A. Schematic of experiment. B. Flow cytometry profiles of geminin RNAi and control RNAi cells plus and minus caffeine treatment. C. Flow cytometry profiles of geminin RNAi and control RNAi cells plus and minus UCN-01 treatment. D. The suppression of re-replication observed in geminin RNAi seen with different inhibitor treatments or with additional p53 knockdown, expressed as a percentage of the amount of re-replication in geminin RNAi cells without inhibitor treatment. E. Demonstration of geminin and p53 knock-down by immunoblotting.

No preferred re-replicating sequences

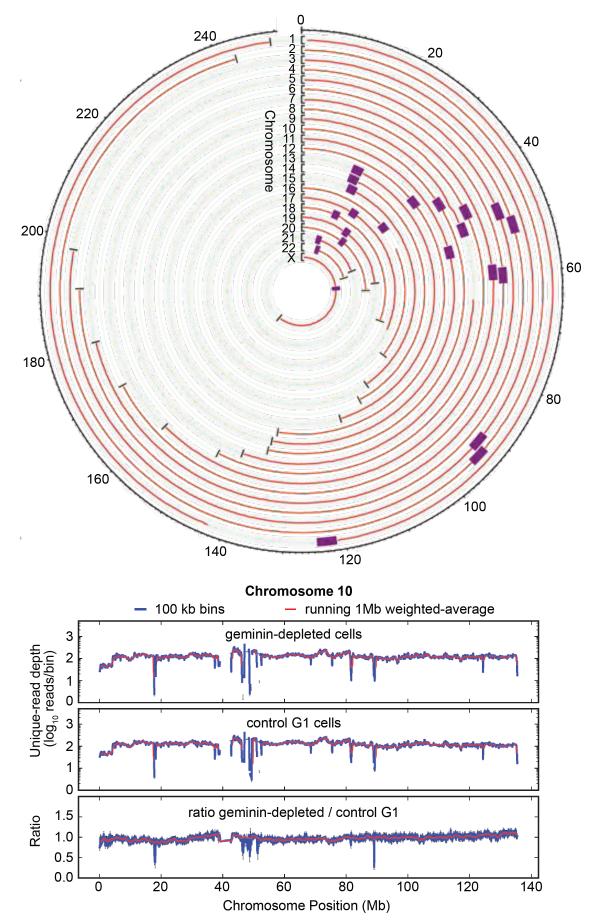

We next investigated the genetic consequences of re-replication and whether re-replication starts from preferred regions as has been reported in S. cerevisiae and D. melanogaster (Ding and MacAlpine, 2010; Green et al., 2010). We used FACS to isolate either G1 (control depleted) cells or >G2 (geminin depleted) cells 48 h after thymidine release. Genomic DNA was isolated from biological triplicates and samples were sent for deep DNA sequencing.

Figure 6 shows the sequencing data as a circle plot, where each circle represents DNA from a single chromosome, shown as a running 1 Mb weighted-average. Deviation from exact circularity, which reflects differences in abundances of the sequenced DNA, is only slight. As an example, chromosome 10 is shown in more detail below the circle plot. In addition to the 1 Mb weighted-average data (red), data grouped with a 100 kb weighted-average is also shown. The abundance ratio typically remains very close to 1 with only minor deviations, which implies that most re-replication occurs stochastically across the genome, rather than preferentially at specific loci. Small-scale (~10%) increases in the ratio are observed for some chromosomes for a few Mb surrounding the centromeres (notably chromosomes 4, 7, 10, 18 & 19) and telomeres (notably chromosomes 6,10, 11,12,19 & 21). The raw data shows some strong, narrow (<10kb), ‘spikes’ which are associated with satellite repeats and are also seen in other genomic sequencing datasets (van Koningsbruggen et al., 2010). Similar results were obtained when DNA from re-replicating cells was used to probe an Agilent whole genome microarray (data not shown). Analysis of the ~10% of sequencing reads that mapped to repetitive chromosomal sequences gave almost identical ratios between control and geminin-depleted samples (see Methods), suggesting that repetitive DNA is not preferentially re-replicated in geminin-depleted cells. Apart from the slight enrichment at centromeres and telomeres, the data therefore provide no evidence that any particular regions of the genome are preferentially re-replicated in response to geminin depletion.

Figure 6. Re-replication occurs throughout the entire genome.

Cells were released from a double thymidine block after prior treatment with either control or geminin RNAi, as in Figure 1A. 48 h after release from the 2nd thymidine block, cells were sorted by FACS according to their DNA content. Cells with a G1 DNA content were collected from the control RNAi sample, and cells with a >G2 DNA content were collected from the geminin RNAi sample. DNA was isolated from the two samples and subjected to deep DNA sequencing. The number of reads in 1 Mb segments of the genome were derived for the two samples, and the ratio of read numbers in geminin-depleted/control G1 samples were calculated. A. Geminin-depleted >G2 / control G1 ratio for all 23 chromosomes. Black brackets show the ratio scale from 0 to 2; the faint green line shows a ratio of 1. Purple boxes denote centromeres. Ticks around the ring show chromosome position in Mb. B. Expanded data for chromosome 10 as exemplar. The number of reads per segment is compared for 1 Mb (red lines) and 100 kb (blue lines) bins. Data for geminin depleted cells with >G2 DNA content (top), control G1 cells (middle), and their ratios are shown (bottom).

Stabilization and overexpression of Cdt1

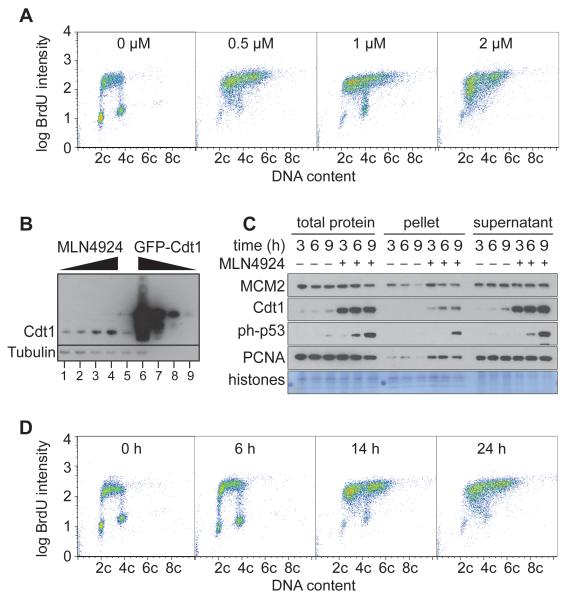

Previous studies have shown that overexpression or stabilization of Cdt1 can result in re-replication (Vaziri et al., 2003; Nishitani et al., 2004; Thomer et al., 2004; Li and Blow, 2005; Maiorano et al., 2005). We therefore investigated whether re-replication in U2OS cells caused by increased Cdt1 levels is similar to re-replication due to loss of geminin. We increased Cdt1 levels either by inhibiting Cdt1 degradation or by overexpressing recombinant Cdt1. Cdt1 degradation is mediated by two ubiquitin ligases: one that is dependent on PCNA and the Cullin CUL4 (Zhong et al., 2003; Arias and Walter, 2006; Nishitani et al., 2006; Senga et al., 2006) and a second dependent on SCF-Skp2 and the Cullin CUL1 (Li et al., 2003; Sugimoto et al., 2004; Nishitani et al., 2006). Cullin activity is dependent on its modification by Nedd8 which can be blocked by the small molecule MLN4924 (Soucy et al., 2009). Treatment of cells with MLN4924 stabilizes Cdt1 in S-phase and causes re-replication, apoptosis and senescence (Soucy et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010; Milhollen et al., 2011).

We treated asynchronous U2OS cells with different concentrations of MLN4924 and examined BrdU and DNA content 24 h later (Figure 7A). Substantial re-replication of DNA was seen at concentrations of 0.5 - 2 μM MLN4924, which caused Cdt1 levels to rise 2 - 5 fold (Fig 7B). This was associated with an enrichment of cells in S phase, and loss of G1 or G2/M cells. The lack of G2 cells is in marked contrast with our results with geminin RNAi, and suggests that unlike geminin depletion, Cdt1 stabilisation induces re-replication directly from S phase without entering G2/M or a subsequent G1 phase. Interestingly we also found that MLN4924 levels higher than 1 μM result in a marked accumulation of cells in early S-phase with reduced amounts of BrdU incorporation.

Figure 7. Re-replication caused by MLN4924.

U2OS cells were transfected with empty expression vector or constructs containing GFP, full-length GFP-Cdt1, GFP-Cdt134-546 or GFP-Cdt11-372.

A. 24 h after treatment with different concentrations of MLN4924, cells were pulsed with BrdU and analysed by flow cytometry. B. Cells were treated with either 0, 0.5, 1 or 2 μM MLN4924 and harvested 24 hr later (lanes 1-4). In parallel, cultures were transfected with constructs to express either GFP (lane 5) or full-length GFP-Cdt1 (lanes 6-9), and after 24 h, GFP-expressing cells were isolated by FACS. Whole cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotted for Cdt1 and tubulin. To compare Cdt1 expression in MLN49234-treated cells and GFP-expressing cells, extract volumes were normalised to give equal tubulin signals (lanes 1-6). In order to assess the degree of GFP-Cdt1 overexpression, extracts of GFP-Cdt1 expressing cells were diluted 10-, 100- and 1000-fold (lanes 7-9). C. Cells were released from a double thymidine block in the presence or absence of 1 μM MLN4924. At different times, total cell extract, soluble protein, and chromatin-enriched fractions were prepared and analysed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. D. At different times after treatment with 1 μM MLN4924, cells were pulsed with BrdU and analysed by flow cytometry.

In order to provide further evidence that cells re-replicating in response to MLN4924 do not need to enter a G2 phase, cells were treated with 1 μM MLN4924 and pulsed with BrdU at different times afterwards (Figure 7C, 7D). Cells appear to continuously incorporate BrdU as they acquire >4C DNA content without passing through a G2 phase where no BrdU incorporation occurs. Within 6 hr after treatment with MLN4924, cells released from a double thymidine block strong phosphorylation of p53 was observed, consistent with re-replication-induced DNA damage occurring during S phase (Fig 7D).

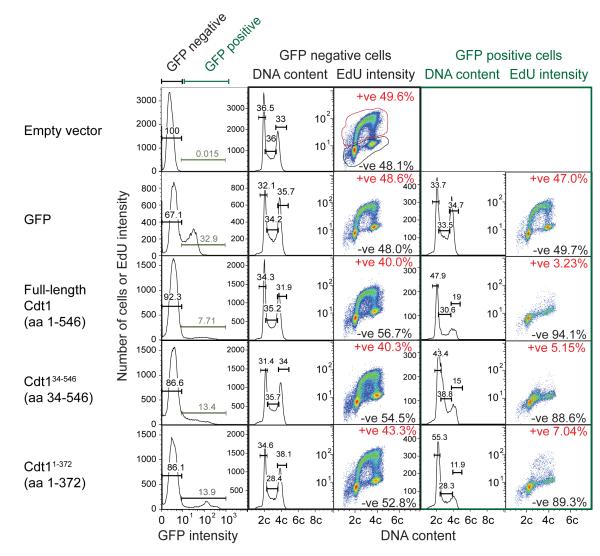

To further increase Cdt1 levels we overexpressed a number of different GFP-tagged Cdt1 constructs that are functionally active but maintain different degrees of cell cycle regulation. These constructs were expressed at levels >100 times higher than endogenous Cdt1 (Fig 8), and led to a strong induction of cell cycle checkpoints and inhibition of EdU incorporation and S phase progression (Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 8. Cdt1 over-expression blocks S phase progression.

U2OS cells were transfected with empty expression vector or constructs containing GFP, full-length GFP-Cdt1, GFP-Cdt134-546 or GFP-Cdt11-372. 48 h later, cells were pulsed with EdU for 20 min and were then stained with anti-GFP antibodies, DNA content, and for incorporated EdU. Cells were then analysed by flow cytometry. Cells were separated by the GFP content (left columns) into low GFP (non-transfected or non-expressers) and high GFP categories. DNA content frequency graphs and EdU versus DNA content is shown for each category.

Discussion

We report here the way that geminin prevents re-replication of chromosomal DNA, and the consequences of a loss of geminin. Geminin depletion in U2OS cells does not significantly affect progression through the first S-phase but triggers activation of the G2/M checkpoint. Cells arrested in G2 then undergo re-firing of origins randomly distributed throughout the genome, ultimately leading to cell death. Activation of the G2/M checkpoint amplifies small defects caused by geminin depletion, thereby creating an ‘all or nothing’ response to re-replication.

Preventing re-replication of DNA is crucial for maintaining genetic stability, and defects in correctly regulating the replication licensing system may make an important contribution to the genetic instability commonly seen in cancer cells (Blow and Gillespie, 2008). Many regulatory mechanisms in animal cells can potentially prevent the relicensing of replication origins once cells have entered S phase. However, the most important of these converge on the down-regulation of Cdt1 activity, and involve either Cdt1 proteolysis or Cdt1 inhibition by geminin (Arias and Walter, 2007; Blow and Dutta, 2005; DePamphilis et al., 2006). Previous work has shown that inhibition or loss of geminin promotes re-replication of chromosomal DNA (Melixetian et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004; Li and Blow, 2005). The results presented in this paper demonstrate how this occurs.

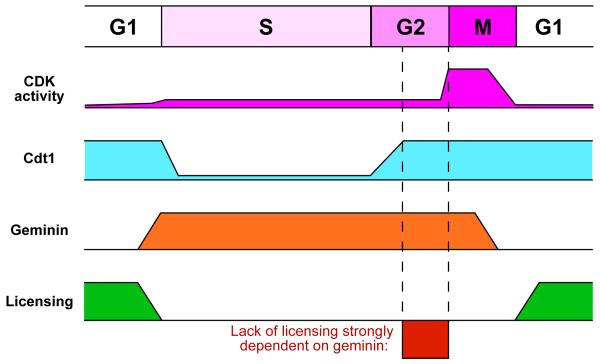

During anaphase and G1 phases, Cdt1 activity is high, geminin activity is low and this allows origin licensing to take place (Figure 9). During S phase, Cdt1 is degraded and geminin is stabilised or activated, both of which can contribute to preventing licensing occurring at this time. We show that synchronised U2OS cells progressing through their first S phase in the absence of geminin exhibit no large-scale defect in DNA replication. This is likely due to the ability of PCNA-mediated Cdt1 degradation during S phase to prevent the re-licensing of DNA that has already been replicated. When Cdt1 levels build up during G2 in cells lacking geminin, re-replication occurs. This suggests that they key role of geminin is to prevent re-licensing and re-replication in G2 phase (Figure 9). In contrast, when Cdt1 proteolysis is suppressed by MLN4924 or when Cdt1 is overexpressed, significant re-replication apparently starts within S phase (our results and Soucy et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010; Milhollen et al., 2011). Geminin depletion does cause problems in the first S phase, however, with 20 – 40% of cells being delayed or blocked in very late S phase or G2. This appears to be due to activation of checkpoint kinases as the G2 block was associated with phosphorylation of p53 and could be abolished by treatment of cells with checkpoint inhibitors such as caffeine or UCN-01.

Figure 9. Cartoon of licensing control by Cdt1 and geminin.

Activity levels of CDKs, Cdt1 and geminin are shown throughout the cell cycle. This allows licensing to take place only during late mitosis and G1. In the absence of geminin, rising Cdt1 levels in G2 can promote re-licensing of replicated DNA, and in the presence of CDK activity, can cause re-replication of DNA.

Although it seems likely that activation of the G2/M checkpoint caused by geminin depletion is a consequence of a small amount of re-replication, we could find no evidence of significant amounts of re-replication having occurred at this stage (data not shown). Similar results were reported by Liu et al, who showed that Cdt1 overexpression in a number of different cell lines causes checkpoint activation in the absence of detectable rereplication (Liu et al., 2007). It is not clear why a small amount of re-replication should cause checkpoint activation. One mechanism by which re-replication induces checkpoint activation is as a consequence of head-to-tail collision of replication forks chasing one another along the same DNA template (Davidson et al., 2006). In order for a head-to-tail collision to occur, re-licensing and re-initiation must occur rapidly after a first initiation event, which seems incompatible with low levels of re-replication occurring in the first S phase after geminin depletion. However, head-to-tail fork collision, which activates checkpoint kinases and causes checkpoint-independent inhibition of replication (Davidson et al., 2006), could well explain the rapid inhibition of DNA replication that occurred when we overexpressed Cdt1 to very high levels.

An alternative explanation for the checkpoint activation that occurs following geminin depletion is that re-replicating forks may be particularly prone to collapse (Green and Li, 2005; Green et al., 2010), possibly due to the re-replicating DNA lacking dormant origins that can rescue replication when forks stall spontaneously (Ge et al., 2007; Ge and Blow, 2010; Blow et al., 2011). This interpretation is consistent with ATR and the Fanconi Anaemia pathway being activated when geminin is lost (Zhu and Dutta, 2006; Liu et al., 2007).

We show here that, paradoxically, activation of the G2/M checkpoint in response to loss of geminin actually promotes re-replication. We show that only after being delayed in G2 do geminin-depleted cells undergo massive re-replication. This is likely because the PCNA-dependent degradation pathway is no longer active in G2, so that Cdt1 levels start to accumulate. G2 is therefore the critical stage of the cell cycle where the presence of geminin is most important for preventing re-replication (Figure 9). By holding cells at this stage, the G2/M checkpoint increases the amount of re-replication that occurs, thereby amplifying the small amounts of re-replication initially caused by geminin depletion. This may represent a protective mechanism to prevent small amounts of re-replication from accumulating in cells, by making re-replication an ‘all or nothing’ response. Consistent with this idea, it was not possible for us to grow out colonies from cells that had undergone re-replication. Even modest amounts of re-replication ultimately led to cell death.

Our conclusions are consistent with several previous studies showing that inhibition of checkpoint signalling or DNA damage response pathways in geminin-defective cells leads to decreased levels of re-replication (Melixetian et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004; Zhu and Dutta, 2006; Lin and Dutta, 2007). These previous reports assumed that reduced levels of re-replication were due to increased apoptosis when DNA damage and checkpoint pathways were inhibited, but they could equally well be explained by reducing the period of time cells spend in G2, as we show here. Consistent with our interpretation, re-replication induced by Cdt1 overexpression is enhanced by inhibition of checkpoint kinases, since Cdt1-induced re-replication occurs directly within S phase (no G2 delay is required) and checkpoint kinases suppress re-initiation of re-licensed origins (Li and Blow, 2005; Davidson et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007).

When we analysed the DNA content of cells that had undergone significant re-replication after geminin depletion, we could find no evidence for the preferential amplification of any specific DNA sequences. This result is in contrast to studies in S. cerevisiae (Green et al., 2010; Green et al., 2006) and Drosophila (Ding and MacAlpine, 2010) which showed preferred amplification of specific DNA regions. It is currently unclear why our results differ from these previous reports. It is hard to draw parallels between our results in human U2OS cells and results obtained in S. cerevisiae, since the mechanisms that suppress licensing in yeast are different from those in animal cells, and yeasts lack geminin. It is more surprising that our results differ from results obtained by depletion of geminin in Drosophila, which showed a preferential re-replication of heterochromatin. Although we detected a small-scale (≈10%) increase in the re-replication around some centromeres (chromosomes 4, 7, 10, 18 and 19) and telomeres (chromosomes 6, 10, 11, 12, 19 and 21), the increase was small and other known heterochromatic regions such as the p arms of chromosome 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22 were not elevated. In addition to using a different cell type, the Drosophila study of Ding et al (2010) differed from ours in using asynchronous cells, and driving re-replication to much higher levels (~8C DNA content), though it is not obvious why these features would be critical for causing preferential re-replication of specific regions.

Interestingly, however, our data is in agreement with a recent study in mouse cells, which showed that G2 phase chromatin lacks determinants of replication timing (Lu et al., 2010). When G2 cells were induced to undergo a complete genome re-duplication, either by incubation in Xenopus egg extracts or following transient CDK inhibition, replication did not follow any defined temporal sequence. It would therefore be expected that in our experiments, where geminin depletion induced re-replication predominantly from a G2 state, re-replication would occur without any defined temporal sequence, so that all chromosome domains might have an equal probability of being re-replicated. As suggested by a previous report (Lin et al., 2010), we would predict that this would not be the case for re-replication induced by Cdt1 overexpression or MLN4924 treatment, as this appears to induce re-replication directly from within S phase. Since MLN4924 is in trial as an anti-cancer agent, it would be interesting to know if different ways of inducing re-replication can be used to exploit different sensitivities between normal and cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, synchronization, siRNA, and drug treatment

U2OS cells (ATCC, Cat. No. HTB-96, Lot. 7658494) were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Cat No.12491-023) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) plus 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Cat. No.15070-063) at 37°C with 5% CO2. For cell cycle synchronization, cells were treated with 2.5 mM thymidine (Sigma, Cat. No. T1895) for 15-16 h, washed twice with 8 ml PBS, released for 10-12 h and treated again with 2.5 mM thymidine for 14-16 h.

Transfections were performed 10 h after release from 1st thymidine block. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine™RNAiMAX (Invitrogen™, Cat.No.13778) >24 h post seeding at 25-50% confluency according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNAi oligos were: geminin (5′AACUUCCAGCCCUGGGGUUAU3′) (at 2.5 - 25 nM); control, (5′CGUACGCGGAAUACUUCGA 3′) (at 2.5 - 25 nM); and ON-TARGET plus SMART pool Human TP53 (Thermo Scientific; Cat No. L-003329-00-0005) (at 10 nM). Caffeine (Calbiochem, Cat. No. 205548) was freshly prepared as a 100 mM stock in H2O and used at 5 mM. MLN4924 (10 mM stock in DMSO) was a gift of Dimitris Xirodimas and Philip Cohen. KU55933 (Tocris Bioscience, Cat. No. 3544) was used at 10 μM. UCN-01 (Calbiochem, Cat no: 539644) was used at 300 nM.

Proliferation and clonogenic assay

For clonogenic assays, 500 cells were plated in triplicate into 6 well dishes and incubated for 10 d. To assess proliferation, cells were harvested at 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h and counted using the Countess automated cell counter (Invitrogen, Cat. No. C10227). After 10 days colonies were washed twice with PSB, fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 20 min, −20°C, stained with crystal violet solution (0.5% crystal violet w/v, 25% methanol) for >2 h and counted.

Chromatin fractionation, immunoblotting and antibodies

For preparation of total cell lysates, cells were trypsinized, washed 2× in PBS, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Pellets were resuspended in 50-200 μl RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% NP-40 1 mM EDTA; 0.5% Na-deoxycholate) plus freshly added inhibitors (1 mM PMSF; 0.1 mM NaOVan; 0.1 mM NaF and 1 μg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin) and incubated on ice, 10 min. Samples were sonicated (310W, Diagenode Bioruptor, Cat. No. UCD-200 TM) for 2× 10 min with 30 s intervals. Samples were centrifuged at 14000×g, 10 min, 4°C. Protein content was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Cat. Nr. 500-0006).

For chromatin fractionation, cells were trypsinized and washed 2× with PBS. The cell pellet was loosened and resuspended in 50-150 μl ice-cold CSK buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.4; 300 mM sucrose; 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2; 0.5% Triton-X-100; 1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM NaOVan, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin and pepstatin). After 15 min on ice, samples were spun 5 min, 5000×g. The supernatant was collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, while the pellet was resuspended, washed 2× in 1 ml CSK buffer and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The chromatin pellet was then resuspended in 50-150μl RIPA buffer and processed as for total cell lysates. Primary antibodies used: phospho-histone H3 (Cell Signalling), cleaved PARP (Asp214), phospho-p53 (Cell Signalling, Ser15), PCNA (PC10), geminin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MCM2 (BD Transduction Laboratories BM28), phospho-histone H2A.X (Upstate), actin (Neomarker). Cdt1 antibody was kindly provided by Zoi Lygerou. Secondary antibodies were HRP conjugated anti-mouse (Sigma, Cat. No. A5278, 1:10000) and HRP conjugated anti-rabbit (Sigma, Cat. No. A0545, 1:50000); or for Cell Signalling primaries HRP conjugated (Cat. No. □ 7074).

Flow cytometry

For cell cycle analysis cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS, resuspended in 70% ice-cold ethanol and stored at −20°C for >30 min. Cells were then washed 2× in PBS plus 1% BSA, 0.2%Triton X-100 and incubated in 0.25-1.0 ml propidium iodide solution (50 μg/ml propidium iodide, 50 μg/ml RNase, 0.1 % Triton-X-100 in PBS) for 15-30 min. Analysis was done using the FACSCalibur™(Becton Dickinson) Flow Cytometer using CellQuest data acquisition software and FlowJo 8.8.4 analysis software.

For 2D BrdU/PI flow cytometry, cells were incubated with 20 μM BrdU, 30 min. For pulse-chase experiments BrdU was removed, cells washed 3× in PBS and incubated with 100 μM thymidine 30 min, after which the thymidine was diluted to 10 μM. Cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS, resuspended in 70% ice-cold ethanol and stored at −20°C. Cells were washed twice in PBS plus 1%BSA, 0.2% TritonX-100 and incubated in 2 M HCl plus 0.2% Triton X-100 for 30 min, room temperature. Cells were then washed with PBS plus 1%BSA, 0.2%Triton X-100 and blocked in PBS plus 5% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h. The solution was replaced by blocking solution containing mouse anti-BrdU antibody (0.5 μg/ml; BD Bioscience, Cat. No. 347580) and incubated 1 h, room temperature. Cells were washed twice in PBS plus 1% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated in blocking solution plus Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab)2 fragment (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen, Cat. No. A21204) for 1 h then washed 2× in PBS plus 1% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100 and stained for DNA content and analyzed as above.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting

Cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS and incubated in DMEM media containing 15 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 30 min, 37°C. Cells were filtered and immediately sorted using the argon ion laser at 345 nm (UV) in a FACS Vantage (with DIVA upgrade, Becton Dickinson).

Cdt1 construct design

The IMAGE clone of human Cdt1 cDNA (Accession BC009410) was obtained from www.geneservice.co.uk in a pOBT7 vector. Initially the cDNA was transferred into the EcoRI/XhoI site of pcDNA3 and subsequently full-length Cdt1 (amino acids 1-546), Cdt134-546 (amino acids 34-546) and Cdt11-372 (amino acids 1 - 372) were PCR amplified and cloned into the EcoRI/KpnI site of pEGFP-N1. Primers:

Fl- Cdt1_fw: 5′ TCCGAATTCATGGAGCAGCGCCGCGTCACC 3′,

Fl- Cdt1_rv: 5′ CCCGGTACCGCTCCCAGCCCCTCCTCAGC 3′,

Deg- Cdt1_fw: AGCGAATTCATGCCCGCACTCCGCGCCCCG 3′,

Lic- Cdt1_rv: ATCGGTACCGAAATCAGGTTGCGGGCC 3′)

Cdt1 Transfection, flow cytometry and antibodies

At 80% confluency 10cm dishes of U2OS cells have been transfected with 6ug pEGFP-N1 or 24ug Fl-Cdt1-GFP, Deg-Cdt1-GFP, Lic-Cdt1-GFP using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen™, Cat. No. 11668) according to the manufactures protocol. About 46h post transfection Click-iT™ EdU (10 μM) was added to the culture medium for 2h. Cells were harvested, fixed with 4% PFA for 20min, permeabilized with 0.3% TX-100, incubated with anti-GFP antibody (1:500, Roche, Cat. No. 11814460001) for 1h and subsequently with Alexa Fluor 488 F (ab)2 fragment of rabbit anti-mouse (2 μg/ml)(Invitrogen™Molecular Probes™, Cat. No. A21204) for 1 h. Afterwards the Click-iT EdU (Invitrogen™, Cat. No. A10202) reaction was performed according to the manufactures instruction and the cells were stained for there DNA content with 7AAD (20ug/ml) (Sigma, Cat. No A9400-1MG). Analysis was done using the FACSCalibur™(Becton Dickinson) Flow Cytometer using the CellQuest data acquisition software and the FlowJo 8.8.4 analysis software.

Solexa Sequencing, data reduction and processing

DNA was isolated from sorted cells using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 69504) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with exceptions at the 2nd wash, which was performed with 80% ethanol and the final step as DNA was eluted in H2O. DNA quality was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA from the control and geminin depleted cells were sequenced at the GenePool Next-Generation Sequencing facility in Edinburgh. 6 samples (3 biological replicates for each treatment) produced more than 82×106, 50 bp long, single-end, sequenced reads. Quality scores were >38/40 along the entire length of the sequences for all samples, and reads needed no clipping prior to alignment. Reads were aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh37/hg19) with the Bowtie short read aligner (v0.12.3). The resulting alignment was filtered for reads that were unique matches to a position in the genome, allowing for up to two mismatches in the sequence alignment. ~80% of the reads fulfilled these criteria. A further 42.0×105 reads were excluded because they mapped to mitochondrial DNA (37.0×105 reads) or the Y chromosome (5.0×105 reads; the U2OS is a female cell line), leaving a total of ~70×106 usable mapped reads covering 3.04×109 bases (average depth=0.02). Data from biological replicates were combined and then initially binned into 10 kb bins, resulting typically in 10s of reads per bin. Characteristic features of centromeres and satellite repeats were observed. Large centromeric gaps in the data persisted throughout further analysis, however the satellite repeat features were typically sharp on the scale of 10 kb and were effectively removed from the data by increased binning and taking the ratio of control and geminin-depleted cells.

Data binning was also increased to 100 kb bins, to ensure that random counting errors for each bin were normally distributed, before the ratio of each of the bins was taken. There were large regions of several chromosomes with read counts per bin more than an order of magnitude less than the genome average. This produced a significant increase in the variance of the ratios in these regions and produced values for the ratios strongly dependant on the binning factor. The origin of the low read counts in these bins is not clear. There was no correlation for any of the classes of repeat annotated by RepeatMasker with the low count bins. Instead we hypothesise that they may be associated with mutations in the U2OS genome relative to the reference sequence.

Of the high-quality reads that mapped to the female core genome (ignoring reads mapping to the Y chromosome or mitochondria), 89.9% (+−0.2%) mapped uniquely to a single location in both the control and geminin-depleted samples. To investigate the re-replication of repetitive DNA, we examined ratios of geminin-depleted/control ratios for the non-unique mapping data. These ratios turned were almost identical to the ratios observed in the unique mapping data. The average difference between the ratio for non-unique reads minus the ratio for unique reads was consistent with zero (−0.0001 ±0.0007) for the 10 kb binned-data, which corresponds to 0.13% ±0.06% as a fraction of the ratio.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by CR-UK studentship C303/A7999 to KKN and CR-UK programme grant C303/A7399 to JJB. We would like to thank Rosemary Clarke for her help with the cell sorting.

References

- Arias EE, Walter JC. PCNA functions as a molecular platform to trigger Cdt1 destruction and prevent re-replication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:84–90. doi: 10.1038/ncb1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias EE, Walter JC. Strength in numbers: preventing rereplication via multiple mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:497–518. doi: 10.1101/gad.1508907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabeni A, Melixetian M, Zamponi R, Masiero L, Marinoni F, Helin K. Human geminin promotes pre-RC formation and DNA replication by stabilizing CDT1 in mitosis. EMBO J. 2004;23:3122–3132. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow JJ, Dutta A. Preventing re-replication of chromosomal DNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:476–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow JJ, Ge XQ, Jackson DA. How dormant origins promote complete genome replication. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow JJ, Gillespie PJ. Replication licensing and cancer--a fatal entanglement? Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:799–806. doi: 10.1038/nrc2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson IF, Li A, Blow JJ. Deregulated replication licensing causes DNA fragmentation consistent with head-to-tail fork collision. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marco V, Gillespie PJ, Li A, Karantzelis N, Christodoulou E, Klompmaker R, van Gerwen S, Fish A, Petoukhov MV, Iliou MS, et al. Quaternary structure of the human Cdt1-Geminin complex regulates DNA replication licensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:19807–19812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905281106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePamphilis ML, Blow JJ, Ghosh S, Saha T, Noguchi K, Vassilev A. Regulating the licensing of DNA replication origins in metazoa. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, MacAlpine DM. Preferential re-replication of Drosophila heterochromatin in the absence of geminin. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrin C, Clarke P, Zech J, Lurz R, Sun J, Uhle S, Li H, Stillman B, Speck C. A double-hexameric MCM2-7 complex is loaded onto origin DNA during licensing of eukaryotic DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:20240–20245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911500106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambus A, Khoudoli GA, Jones RC, Blow JJ. MCM2-7 form double hexamers at licensed origins in Xenopus egg extract. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:11855–11864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XQ, Blow JJ. Chk1 inhibits replication factory activation but allows dormant origin firing in existing factories. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:1285–1297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XQ, Jackson DA, Blow JJ. Dormant origins licensed by excess Mcm2-7 are required for human cells to survive replicative stress. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3331–3341. doi: 10.1101/gad.457807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie PJ, Li A, Blow JJ. Reconstitution of licensed replication origins on Xenopus sperm nuclei using purified proteins. BMC Biochem. 2001;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BM, Finn KJ, Li JJ. Loss of DNA replication control is a potent inducer of gene amplification. Science. 2010;329:943–946. doi: 10.1126/science.1190966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BM, Li JJ. Loss of rereplication control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in extensive DNA damage. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:421–432. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BM, Morreale RJ, Ozaydin B, Derisi JL, Li JJ. Genome-wide mapping of DNA synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals that mechanisms preventing reinitiation of DNA replication are not redundant. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:2401–2414. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JR, Lee HO, Bunker BD, Dorn ES, Rogers GC, Duronio RJ, Cook JG. Cdt1 and Cdc6 are destabilized by rereplication-induced DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:25356–25363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802667200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson B, Li A, Tada S, Blow JJ. Geminin becomes activated as an inhibitor of Cdt1/RLF-B following nuclear import. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:678–683. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00778-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisielewska J, Blow JJ. Dynamic interactions of high Cdt1 and geminin levels regulate S phase in early Xenopus embryos. Development. 2012;139:63–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.068676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Liu E, Wu X. The Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex plays an important role in the prevention of DNA rereplication in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:32243–32255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HO, Zacharek SJ, Xiong Y, Duronio RJ. Cell type-dependent requirement for PIP box-regulated Cdt1 destruction during S phase. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:3639–3653. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Blow JJ. Non-proteolytic inactivation of geminin requires CDK-dependent ubiquitination. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:260–267. doi: 10.1038/ncb1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Blow JJ. Cdt1 downregulation by proteolysis and geminin inhibition prevents DNA re-replication in Xenopus. EMBO J. 2005;24:395–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhao Q, Liao R, Sun P, Wu X. The SCF(Skp2) ubiquitin ligase complex interacts with the human replication licensing factor Cdt1 and regulates Cdt1 degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30854–30858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Dutta A. ATR pathway is the primary pathway for activating G2/M checkpoint induction after re-replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30357–30362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Milhollen MA, Smith PG, Narayanan U, Dutta A. NEDD8-targeting drug MLN4924 elicits DNA rereplication by stabilizing Cdt1 in S phase, triggering checkpoint activation, apoptosis, and senescence in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10310–10320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Lee AY, Chiba T, Olson E, Sun P, Wu X. The ATR-mediated S phase checkpoint prevents rereplication in mammalian cells when licensing control is disrupted. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:643–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Li F, Murphy CS, Davidson MW, Gilbert DM. G2 phase chromatin lacks determinants of replication timing. J. Cell Biol. 2010;189:967–980. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzmann M, Maiorano D, Mechali M. A Cdt1-geminin complex licenses chromatin for DNA replication and prevents rereplication during S phase in Xenopus. EMBO J. 2006;25:5764–5774. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorano D, Krasinska L, Lutzmann M, Mechali M. Recombinant Cdt1 induces rereplication of G2 nuclei in Xenopus egg extracts. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry TJ, Kirschner MW. Geminin, an inhibitor of DNA replication, is degraded during mitosis. Cell. 1998;93:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melixetian M, Ballabeni A, Masiero L, Gasparini P, Zamponi R, Bartek J, Lukas J, Helin K. Loss of Geminin induces rereplication in the presence of functional p53. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:473–482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylov IS, Kondo T, Jones L, Ryzhikov S, Tanaka J, Zheng J, Higa LA, Minamino N, Cooley L, Zhang H. Control of DNA replication and chromosome ploidy by geminin and cyclin A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:1868–1880. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1868-1880.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhollen MA, Narayanan U, Soucy TA, Veiby PO, Smith PG, Amidon B. Inhibition of NEDD8-Activating Enzyme Induces Rereplication and Apoptosis in Human Tumor Cells Consistent with Deregulating CDT1 Turnover. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3042–3051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H, Lygerou Z, Nishimoto T. Proteolysis of DNA replication licensing factor Cdt1 in S-phase is performed independently of geminin through its N-terminal region. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30807–30816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H, Sugimoto N, Roukos V, Nakanishi Y, Saijo M, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T, Nakayama KI, Nakayama K, Fujita M, et al. Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCF-Skp2 and DDB1-Cul4, target human Cdt1 for proteolysis. EMBO J. 2006;25:1126–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus D, Beuron F, Tolun G, Griffith JD, Morris EP, Diffley JF. Concerted loading of Mcm2-7 double hexamers around DNA during DNA replication origin licensing. Cell. 2009;139:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senga T, Sivaprasad U, Zhu W, Park JH, Arias EE, Walter JC, Dutta A. PCNA is a cofactor for Cdt1 degradation by CUL4/DDB1-mediated N-terminal ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6246–6252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Berger AJ, Gavin JM, Adhikari S, Brownell JE, Burke KE, Cardin DP, Critchley S, et al. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature. 2009;458:732–736. doi: 10.1038/nature07884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto N, Tatsumi Y, Tsurumi T, Matsukage A, Kiyono T, Nishitani H, Fujita M. Cdt1 phosphorylation by cyclin A-dependent kinases negatively regulates its function without affecting geminin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19691–19697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S, Li A, Maiorano D, Mechali M, Blow JJ. Repression of origin assembly in metaphase depends on inhibition of RLF-B/Cdt1 by geminin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:107–113. doi: 10.1038/35055000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomer M, May NR, Aggarwal BD, Kwok G, Calvi BR. Drosophila double-parked is sufficient to induce re-replication during development and is regulated by cyclin E/CDK2. Development. 2004;131:4807–4818. doi: 10.1242/dev.01348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Koningsbruggen S, Gierlinski M, Schofield P, Martin D, Barton GJ, Ariyurek Y, den Dunnen JT, Lamond AI. High-resolution whole-genome sequencing reveals that specific chromatin domains from most human chromosomes associate with nucleoli. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:3735–3748. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri C, Saxena S, Jeon Y, Lee C, Murata K, Machida Y, Wagle N, Hwang DS, Dutta A. A p53-dependent checkpoint pathway prevents rereplication. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlegel JA, Dwyer BT, Dhar SK, Cvetic C, Walter JC, Dutta A. Inhibition of eukaryotic DNA replication by geminin binding to Cdt1. Science. 2000;290:2309–2312. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang VS, Carter SA, Hyland SJ, Tachibana-Konwalski K, Laskey RA, Gonzalez MA. Geminin escapes degradation in g1 of mouse pluripotent cells and mediates the expression of oct4, sox2, and nanog. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Feng H, Santiago FE, Kipreos ET. CUL-4 ubiquitin ligase maintains genome stability by restraining DNA-replication licensing. Nature. 2003;423:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature01747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Chen Y, Dutta A. Rereplication by depletion of geminin is seen regardless of p53 status and activates a G2/M checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:7140–7150. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7140-7150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, DePamphilis ML. Selective killing of cancer cells by suppression of geminin activity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4870–4877. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Dutta A. An ATR- and BRCA1-mediated Fanconi anemia pathway is required for activating the G2/M checkpoint and DNA damage repair upon rereplication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:4601–4611. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02141-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.