Abstract

In this study, we examine whether and to what extent the health insurance system in Turkey provided adequate protection against high out of pocket expenditures in the period prior to “The Health Transformation Programme”. Furthermore, we examine the distribution of out of pocket expenditures by demographic characteristics, poverty status, health service type, access to health care and self-reported health status. We employ the 2002/03 National Household Health Expenditure Survey data to analyze financial burden of health care expenditure. Following the literature, we define high burdens as expenses above 10 and 20% of income. We find that 19% of the nonelderly population were living in families spending more than 10% of family income and that 14% of the nonelderly population were living in families spending more than 20% of family income on health care. Furthermore, the poor and those living in economically less developed regions had the greatest risk of high out of pocket burdens. The risk of high financial burdens varied by the type of insurance among the insured due to differences in benefits among the five separate public schemes that provided health insurance in the pre-reform period. Our results are robust to three alternative specifications of the burden measure and including elderly adults in the sample population. We see that prior to the reforms there were not adequate protection against high health expenditures. Our study provides a baseline against which policymakers can measure the success of the health care reform in terms of providing financial protection.

Keywords: Out of Pocket expenditures, Financial burden, Health care reform, Turkey

Introduction

In 2001, Turkey initiated a series of reforms to align its health care system with the health regulations of the European Union and the OECD countries. The “Health Transformation Program” (HTP) was launched in 2003 (1, 2). The Universal Health Insurance (UHI) system was implemented in October, 2008. Prior to the UHI, health insurance was provided by five different public schemes each with separate provider networks. UHI will provide health services under one scheme. Providing financial protection is one of the main goals of the Turkish health care reform.

However, to date there is only one study that examines the size of out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditures for public insurees prior to HTP reforms: Erus and Aktakke (3). They consider the OOP health expenditures concerning the insurance schemes and some demographic characteristics of the insurees by using the 2003 Household Budget Survey. But, their study does not provide the information regarding the distribution of OOP expenditures by health service type, access to health care and self reported health status. Therefore, there is still a need of baseline criteria to evaluate the performance of the reforms in terms of providing adequate financial protection. Our paper fills this gap by examining the distribution of health care expenditure burdens for the period prior to the UHI implemented in 2008. We employ the National Household Health and Expenditure Survey 2002–2003 which has been conducted as part of Turkish Ministry of Heath’s effort to develop and implement ‘National Health Accounts’ that are in line with the standards of European Union and OECD Health Accounts System. The survey is specifically designed to collect health related expenditures as well as detailed information on health utilization, health status and socio-demographic variables.

We examine the risk of high financial burden due to out of pocket health spending for the non elderly population by insurance status. Furthermore, we examine the distribution of out of pocket expenditures by service type, access to care and self-reported health status. Indeed we provide robustness check considering the three alternative specifications of the burden measure, using total expenditures instead of income to define capacity to pay, adding imputed rent to income for homeowners, and including elderly adults in the sample population.

Our study provides a baseline against which policymakers can measure the success of the health care reform in terms of providing financial protection. Indeed, we provide information on insurance coverage and access to care to present more comprehensive picture of Turkey’s health care system as it affects different segments of the population.

Background

Turkey’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was $5,045 in 2005. Total health care expenditures were $27.6 million in 2005 and health expenses accounted for 5.7% of the GDP (4). Turkey’s population was 72 million in 2005. The age composition of Turkey is much younger than that of other OECD countries: In Turkey, children 0 to 14 years constitute 28.4% of the population while individuals aged 65 and above constitute only 5.9%. In other OECD countries, on average children 0 to 14 years constitute 17.4% and those aged 65 and above constitute 15% of the population. Life expectancy in Turkey was 74 years for women and 69.1 years for men in 2006. The infant mortality rate in Turkey (22.6 per 1,000 live births in 2006) is higher than other OECD countries’ average (4.7 per 1000 live births in 2005) (4).

Prior to HTP reforms Health care delivery system

Prior to HTP reforms provision of health care was complex and fragmented. There were three main public providers: the Ministry of Health (MoH), the Social Insurance Organization (SSK), and universities. The Ministry of Health, the largest provider of health care in Turkey, provided primary, secondary, and tertiary care through its own primary health care facilities and hospitals. It was the only provider of preventive services. In 2002, MoH managed 654 hospitals that accounted for 57% of hospitals and approximately 50% of total hospital beds. SSK provided health care services through its 120 hospitals and other health facilities. University hospitals (56 hospitals) were the main provider of tertiary care, though their share in the overall delivery system was small. With 241 hospitals, the private sector comprised 20% of total number of hospitals. However, the private sector accounted for only 6.7% of total hospital beds (5). Private sector had major contribution to health delivery system in Turkey through its outpatient clinics. Doctors were allowed to work part time both in a public facility and in their private clinics (6).

Health care financing

Before the HTP reforms, health care financing was also complex and fragmented. There were three different social security schemes: SSK, Government Employees Retirement Fund (GERF), and the Social Insurance Agency of Merchants, Artisans and the Self-employed (Bag-Kur). These security funds provided both pension and health insurance. SSK covered private sector employees and blue-collar public sector employees, Bag-Kur covered self-employed people and GERF covered retired civil servants. In addition, health spending of active civil servants was financed from the general government budget. Moreover, the Green Card scheme, which provided free health services for the poor was directly funded by the government budget.1 In addition to these five schemes, the Social Solidarity Fund, which was financed through the government budget, covered the health expenses of persons who were not eligible for Green Card and could not afford health care.

Differences in benefits between the public insurance schemes

The five separate schemes had varying benefit levels. GERF had the most generous benefits package, providing all outpatient and inpatient care, medical and non-medical services. GERF provided access to all types of facilities: state facilities, universities, and the private sector facilities (2). Active civil servants were allowed to use public facilities and could be referred to the private facilities. The SSK covered all inpatient and outpatient expenditures, but did not provide nor pay for preventive care services. The SSK provided services directly through its own facilities. However, members could be referred to the MoH, university, and less frequently, private hospitals. The SSK purchased a significant share of drugs from manufacturers and but also manufactured generic drugs; and its members obtained pharmaceuticals through SSK hospitals and dispensaries.

Bag-Kur did not operate its own health facilities, and instead contracted with over 133 health organizations such as the Ministry of Health and SSK facilities, university hospitals, private hospitals, nongovernmental organizations and pharmacies for inpatient services, outpatient services and pharmaceuticals (7). The Green Card scheme covered inpatient care only at the Ministry of Health hospitals and referrals to university hospitals. However, the Green Card holders could submit their outpatient expenses to the Solidarity Fund but these requests were (totally or partially) covered by the Solidarity Fund only if the Fund had enough sources.

Prior to the health care reform, only GERF and Bag-Kur members had access to private facilities for dental care. Furthermore, only GERF members had direct access to university hospitals, while SSK members had to be refereed from other public hospitals. Bag-Kur members were required to pay for expenses incurred at university hospitals and private hospitals out of pocket, then they were reimbursed from Bag-Kur subject to quantity and price constraints. For services that were not provided by contracted hospitals, patients were referred to private centers. SSK members only had access to contracted centers (8).

Insurance premiums

GERF did not collect premiums for health insurance. It financed its health care services through the GERF budget. GERF budget was composed of pension contributions: active civil servants’ contributions as employees (16% of salary) and the government’s contribution as employer (20% of salary). Moreover, the difference between GERF funds and expenses were subsidized from the government’s general budget.

Active civil servants’ health expenses were not covered by GERF and their expenses were financed through allocations from the government budget. The SSK was mainly funded through premiums based on payroll wages.2 SSK actives had to pay 5% of payroll wage as employee contribution and employers paid 6 % of payroll wage.

Premium payment was a significant burden especially for Bag-Kur active members, since there was no other contribution from other sources. Bag-Kur’s premium was 20% of Bag-Kur active member’s average income. Bag-Kur retirees paid for health insurance through a 10% deduction from their pension.

Co-payment for outpatient services were the same among GERF, SSK and Bag-Kur. For outpatient pharmaceuticals, prosthesis and other healing devices co-payments rates were 20% and 10% respectively for active members and pensioners.3 Furthermore, SSK members and their dependents had copays per outpatient visit.4 However, copay rates were reduced for consultation and surgery at SSK facilities.

Crucial HTP Reforms

The SSK health facilities were transferred to the MoH thereby separating the purchaser (SSK) and the provider of health services (MoH). The SSK members gained access to all MoH hospitals. Performance based supplementary payment system was initiated in the MoH health facilities. Health information systems were improved. Moreover, the Green Card scheme started to cover outpatient health expenses. Both Green Card holders and SSK members gained access to private pharmacies. Social Security Institution (SSI) was established; combining SSK, Bag-Kur and GERF into one establishment.

Most significantly, in 2008 UHI was initiated which aimed to extend GERF benefits to all insured people. Thus, the benefit generosity across the various health insurance schemes is unified under UHI. Ultimately, UHI will cover the whole population. However, the reform will take some time; active civil servants and green card holders will be covered by UHI in three years.5

Previous Literature

There are two alternative methods that have been used to examine high financial burdens or catastrophic health expenditures. One line of research uses expenditures to measure a household’s capacity to pay (9–11). Total consumption expenditure of the household is taken to be the effective income, assuming that consumption is a more accurate reflection of purchasing power than income reported in household surveys. Expenditures are defined as catastrophic if they exceed 40% of “income” remaining after subsistence needs (food expenditures) have been met. The other line of research, which we follow in this study, uses income to measure a household’s capacity to pay (12–15). This method is subject to potential bias due to underreporting of income and may overestimate the prevalence of catastrophic burdens. However, it is preferred to the first method in that using total expenditures to measure capacity to pay underestimates the prevalence of catastrophic expenditures. For household with exceptionally high health care expenditures in a given period, using total expenditures as the denominator of the burden measure leads one to underestimate the burden of health expenditures. Since health care expenditures would be included in the total expenditures. Furthermore, using total expenditures to measure capacity to pay underestimates burdens for families who borrow or use their savings to pay for health care.

Methods and Data

We used data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. This survey was conducted as part of Turkish Ministry of Heath’s effort to develop and implement ‘National Health Accounts’ that are in line with the standards of European Union and OECD Health Accounts System.6 The household survey contains detailed information on health insurance coverage, health utilization, and out of pocket spending (OOPS) on healthcare as well as other sociodemographic variables. Two rounds of the survey were administered during September–October 2002 and during March–April 2003. The survey had a 92% response rate with 9,805 out of 10,675 households completing the survey.7 Sample size is 39,411 for the nonelderly (younger than 65 years) population used in this study. Our results are weighted to be nationally representative of the Turkish civilian, noninstitutionalized population younger than 65 years.8 Standard errors have been corrected for the complex design of the survey using SPSS. In all tables presented, t-tests were utilized to compare the means.

Health care burdens are defined as the share of out of pocket health care expenditures within family income. We construct annual burden measures, scaling up expenditures reported for the previous six-months to annual levels. Burdens are constructed at the family level and then assigned to individuals within the family.9 The burden measure includes all out of pocket payments for healthcare products and services. Premium payments and indirect health expenditures are not included.10 The survey did not collect data on premiums for public insurance schemes.11 Thus we could not include premiums in the financial burden measures.

Following previous literature, we define high burdens as OOP health care spending above 10 and 20% of family income12. The survey data have been previously edited by MoH and missing and low household incomes have been recoded as zero. The zero-recoded cases are 7,6% of our sample. In cases where family income is zero, we replaced income with a week’s minimum wage to construct the burden measure.13

We also present burdens by demographic characteristics and by poverty status. We use TUIK’s poverty line (PL) based on food and non-food expenses:14 poor (income< P), low-income (100% PL <income<200% PL), middle-income (200% Pl<income< 400% Pl), and high-income (income > 400% PL).15

Results

Burdens by Insurance Status

Table 1 shows that the publicly provided health insurances schemes covered 65.4% of the nonelderly population (43.3 million). SSK covered 33.6% of the population (active SSK and pensioned), Bag-Kur insures 11.0% of the population (active and pensioned), and GERF covers 4.4% of the population. Active civil servants and their dependants account for 7.8% and Green Card holders account for 8.7% of the population. Uninsured population (22 million) accounted for 33.7% of the nonelderly population. Private insurance companies cover 0.3 million individuals (0.4% of non-elderly population). The remaining (0.5% of non-elderly population) had other health coverage16.

Table 1:

Components of family out-of-pocket burdens, Turkey, 2002–2003

| Insurance Status | Population (*1000) | Family Income (US $)† | Out-of-pocket spending on care (US $)† | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 10 % | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 20 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turkey Sample | 66085 | 3904 (162.4) | 351 (21.9) | 18.9 (0.6) | 14.4 (0.6) |

| Active Civil Servants | 5150 | 6112 (467.0) | 209 (48.2) | 8.8 (1.1) | 5.7 (0.9) |

| SSK active | 15181 | 4571** (197.4) | 367* (59.9) | 15.9** (0.9) | 10.6** (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur active | 5562 | 5229 (894.3) | 387* (51.7) | 21.5** (1.7) | 16.8** (1.6) |

| GERF | 2899 | 5179 (209.8) | 211 (36.1) | 10 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.1) |

| SSK retirees | 7012 | 4064** (121.3) | 299 (43.1) | 15.2** (1.1) | 9.8** (0.9) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 1696 | 3784** (259.3) | 331 (93.0) | 17.6** (2.1) | 12.2** (1.7) |

| Green Card | 5752 | 1671** (101.3) | 286 (34.5) | 25.9** (1.8) | 22.2** (1.7) |

| Uninsured | 22239 | 2867** (184.8) | 424** (33.2) | 23.4** (1.1) | 19.3** (1.0) |

| Private Insurance | 273 | 13360** (2495.6) | 153 (53.3) | 5.5 (2.7) | 1.5** (1.0) |

| Others | 323 | 3382** (446.3) | 178 (53.1) | 13.4 (3.5) | 5.7 (2.1) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. Survey has been done in September 2002/ April 2003 period. Thus we employed average exchange rate of this period (1 US $ = 1.6 YTL) to convert family income and OOP spending on health into dollar terms.

Notes:

Standard errors of means are in parentheses. Statistical significance denotes difference from the reference category which is active civil servants.

P<0.05

P<0.01

Overall, 19% of the nonelderly population (12.6 million) was living in families spending more than 10% of family income on health care. In other words, approximately one out of every five persons incurred burdens that exceeded 10% of family income. Moreover, 14% of the nonelderly population was living in families spending more than 20% of family income on health care.

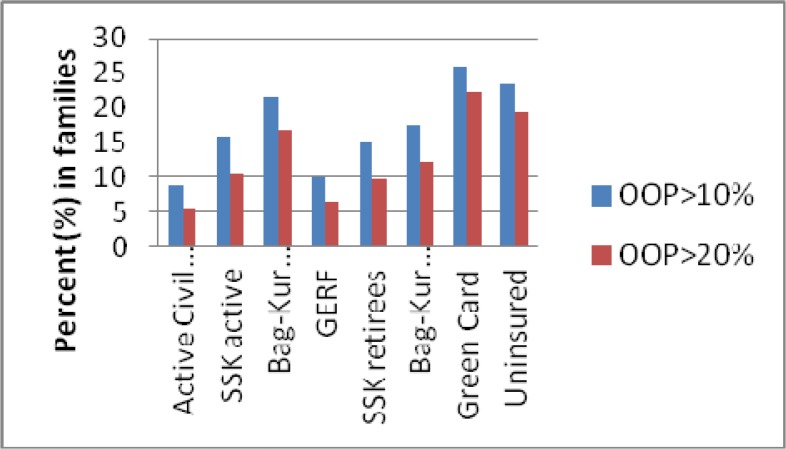

Secondly, there are significant differences in the risk of high burdens by insurance type. Green Card holders are the most likely and active civil servants are the least likely to bear high burdens. Among the active members, Bag-Kur actives had the greatest risk, while active civil servants had the lowest risk of high burdens. Similarly, among retirees Bag-Kur retirees had the greatest risk while retired civil servants (GERF) had the lowest risk. (Fig. 1). Active civil servants had the highest income ($6112) and lowest OOP spending ($209). Retired civil servants (GERF) had higher income ($5179) and lower OOP spending ($211) compared to Bag-Kur and SSK retirees. However, out of pocket payments among the retired insurees are not statistically significantly different from each other.

Fig 1:

Risk of high burdens by insurance status

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey

Table 1 also shows that Green Card holders faced the greatest risk of high burdens. Green Holders had the lowest average income level ($1671). More significantly, their average out-of-pocket spending ($286) is higher than oop spending among active civil servants and retired civil servants (GERF) who had the highest income among the nonelderly population.

Burdens by demographic characteristics and poverty status

Table 2 shows risk of high burdens by age, sex, region, urbanicity, cities and by poverty status. Differences in risk of high burdens are significant by age, sex region, urbanicity, by cities and by poverty status. Adults aged 55 to 64 years are least likely (%16.6) and the juniors aged 0 to 17 years are most likely (%20.7) to incur health care financial burdens exceeding 10% of family income. The high rate of uninsured and low family income level is the most important reasons that drive the juniors’ health expenses burden up.17 People living in the East region were most likely (24.2%) and those living in Central Anatolia region were least likely (15.7%) to bear high burdens. East region of Turkey is economically less developed and the number of insured people is low compared to other regions.

Table 2:

Risk of high burdens by demographic characteristics and poverty status, among the nonelderly population in Turkey, 2002–2003

| Characteristics | Population (Thousands) | Persons with total family burden | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.10 of Family Income | >0.20 of Family Income | |||

| Total | 66,085 | |||

| Age | 0–17 | 23,834 | 20.7 | 16.3 |

| 18–34 | 20,826 | 18.8 | 14.2* | |

| 35–54 | 17,052 | 17** | 12.4** | |

| 55–64 | 4,374 | 16.6** | 12.8** | |

| Sex | Male | 33,182 | 18.6 | 14.2 |

| Female | 32,903 | 19.2 | 14.6 | |

| Region | West | 28,531 | 18.5 | 13.5 |

| South | 7,763 | 18.7 | 15 | |

| Middle | 11,216 | 15.7* | 10.8* | |

| North | 7,179 | 17 | 13.2 | |

| East-South East | 11,396 | 24.2* | 20.6** | |

| Urbanicity | Rural | 20,738 | 21.5 | 17.7 |

| Urban | 27,258 | 17.2** | 12.8** | |

| Major cities | Ankara | 3,423 | 14.6 | 9.2 |

| İstanbul | 11,757 | 20.5* | 14.6** | |

| İzmir | 2,909 | 14.2 | 11.1 | |

| Poverty status † | Poor | 34,043 | 23.3 | 19.4 |

| Low Income | 17,699 | 14.3** | 9** | |

| Middle Income | 8,507 | 13** | 7.3** | |

| High Income | 3,311 | 5.6** | 2.6** | |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey.

Note: Standard errors of means are available upon request.

Poverty line by household size from Turkish Statistical Institute, (TUIK)). Poverty line is calculated including food and non-food expenses. TUIK provides poverty lines for families composed of at most 10 persons. In our analyze families with more than 10 persons constitutes 4% of our sample (2.5 million individuals). Of these, only 3% of them incurred health care expenses greater than 10% of family income. Thus, they are excluded form the analysis. Statistical significance denotes difference from the reference category which is the first row of each characteristics section.

P<0.05

P<0.01

People living in Ankara and Izmir (second and third largest cities) were less likely to incur high burdens compared to those in Istanbul. While the overall uninsurance rate for urban areas was 28.2%, 32.8 % of the population in Istanbul was uninsured. Moreover, it is seen that people living in rural area are more likely to incur high burdens compared to those in urban area. Also, it is observed that the risks of high burdens are greater among lower income groups. The poor had the greatest risk of high burdens, while the high-income faced the lowest risk.

Distribution of out of pocket spending by service type

Table 3 shows average out of pocket expenditures and the distribution of out of pocket spending by service type at the person-level. Average out of pocket spending was significantly higher among those with burdens above 20% of income ($435) compared to persons with burdens less than 20% of income ($14). Among those with burdens above 20% of income, ambulatory care accounted for 46.8% and prescription medications accounted for 30.8% of out of pocket expenditures. Among active civil servants, hospital stays accounted for 14.4%, ambulatory care visits accounted for 27.8%, prescription medications accounted for 48.3% and other services accounted for 9.5% of out of pocket expenditures. Table 3 also shows that among all insurance types except Green Card scheme, ambulatory care visits and prescription medications account for the largest share of out of pocket expenditures. For Green Card holders hospital stays have greater share than ambulatory care visits.

Table 3:

Distribution of out-of-pocket expenditures by service type, among the nonelderly population in Turkey 2002–2003

| US$ average oop expenses | (%) Distribution of average OOP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Stays | Ambulatory Care Visits | Prescription Medication | Other Services | ||

| Total | 74.3 (4.4) | 17.3 (0.8) | 37.3 (2.4) | 39.3 (2.4) | 6.1 (0.5) |

| persons with burden≤ %20 of income | 13.5 (0.7) | 18.5 (1.0) | 30 (4.2) | 45.9 (4.2) | 5.6 (0.7) |

| persons with burden> %20 of income insurance coverage | 435.3** (27.9) | 15.8 (1.1) | 46.8** (1.5) | 30.8** (1.4) | 6.7 (0.7) |

| Active Civil Servants | 62.6 (20.6) | 14.4 (2.5) | 27.8 (3.1) | 48.3 (3.6) | 9.5 (1.9) |

| SSK active | 79.8 (10.4) | 16 (1.4) | 39.9** (2.0) | 35.9** (2.0) | 8.2 (1.2) |

| Bag-Kur active | 88.9 (14.0) | 15.1 (2.2) | 40.2* (4.8) | 41 (4.6) | 3.6** (1.0) |

| GERF | 46.9 (11.1) | 20.1 (3.8) | 29 (5.4) | 46 (5.4) | 4.9 (2.1) |

| SSK pensioned | 89.9 (15.8) | 13.6 (1.4) | 41.6** (2.1) | 41.3 (2.1) | 3.6** (1.1) |

| Bag-Kur pensioned | 99.3 (27.7) | 17.2 (3.3) | 41.4* (4.6) | 37.9 (4.8) | 3.4* (1.5) |

| Green Card | 48.1 (5.3) | 32.4** (2.7) | 29 (2.7) | 34.8** (2.8) | 3.8** (1.1) |

| Uninsured | 73.9 (5.9) | 17.2 (1.3) | 37.7 (8.5) | 38.8 (8.5) | 6.3 (1.0) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. Survey has been done in September 2002/ April 2003 period. Thus we employed average exchange rate of this period (1 US $ = 1.6 YTL) to convert family income and OOP spending on health into dollar terms.

Notes: Standard errors of means are in parentheses.

[*] Difference from the reference category is significant at 1 [5]% level. Those with burden <20% of income are the reference category. The reference category in the bottom section is active civil servants.

Access to health services by insurance coverage

Table 4 shows that the % with any health care use was significantly higher among the active civil servants compared to SSK actives, Bag-Kur actives and Green card holders. Similarly, the % with any health care use were significantly higher among the retired civil servants (GERF) compared to SSK and Bag-Kur retirees. There was no significant difference among the public health insurance schemes in access to inpatient care except Green card scheme. The % with inpatient care use was significantly higher for Green card holders compared to active civil servants. Before the HTP only inpatient care was covered for Green card neither outpatient nor medication (except during hospitalization). Consequently, it was observed that the %s with any outpatient care, any preventive care and any medication were significantly lower for Green card holders compared to active civil servants.

Table 4:

Health care use by insurance type

| Insurance Coverage | Outpatient (%) | Inpatient (%) | Preventive Care (%) | Medication† (%) | Any Health Care Use(%)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Turkey Sample) | 9.3 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 6.5 (0.2) | 12.9 (0.3) |

| Active Civil Servants | 12.8 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.2) | 8.3 (0.6) | 16.6 (0.7) |

| SSK active | 9.6** (0.4) | 3.6 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.1) | 6.5** (0.3) | 13.9** (0.4) |

| Bag-Kur active | 9.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.3) | 0.8** (0.2) | 7.5 (0.6) | 13** (0.7) |

| GERF | 17.9** (1.1) | 3.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 13.1** (0.9) | 21.5** (1.1) |

| SSK retirees | 14 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.3) | 0.8** (0.1) | 9.7 (0.6) | 17.5 (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 15.6 (1.3) | 4.4 (0.7) | 0.6** (0.3) | 11.9** (1.3) | 19.4 (1.6) |

| Green Card | 8.1** (0.6) | 5.6** (0.5) | 0.9** (0.2) | 4.7** (0.4) | 13.7** (0.8) |

| Uninsured | 5.5** (0.3) | 1.8** (0.1) | 1.1* (0.1) | 4** (0.2) | 8** (0.3) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey.

Notes:

Included prescription medication during hospitalization, outpatient and/or preventive health care.

Any outpatient, any inpatient, any preventive care and any prescription medication. Standard errors of means are in parentheses.

[*] Difference from the reference category (active civil servants) is significant at 1 [5]% level.

Table 4 also shows that the % with any medication use was significantly lower among the SSK actives compared to active civil servants. It was noted that prior the HTP system SSK members had limited access to medication only through SSK pharmacies. Lastly, the % with any outpatient care, any medication use, any preventive care, any inpatient care and any health care use were significantly lower among the uninsured compared to among the active civil servants.

Self-reported health status by insurance coverage

Table 5 shows the differences in self-reported health status by insurance type. As in access to care measures, we find that the % reporting good or very good health is higher among active civil servants compared to SSK and Bag-Kur actives as well as Green card holders and the uninsured. Similarly, the % reporting good or very good health is higher among retired civil servants compared to SSK and Bag-Kur retirees.

Table 5:

Self reported health status by insurance type among the nonelderly population in Turkey, 2002–2003

| Insurance Status | Number of Persons (×1000) | Percent of total population | Very Bad (in %) | Bad (in %) | Average (in %) | Good or very good (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total† | 50820 | 100 | 0.3 (0.0) | 3.6 (0.2) | 13.6 (0.4) | 82.5 (0.5) |

| Active Civil Servants | 3906 | 7.7 | 0.1 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.3) | 10.8 (0.9) | 87.2 (1.1) |

| SSK active | 11150 | 21.9 | 0.2 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.2) | 11.0 (0.6) | 86.9 (0.6) |

| Bag-Kur active | 4218 | 8.3 | 0.2 (0.1) | 2.9 (0.4) | 11.1 (0.9) | 85.8 (1.1) |

| GERF | 2678 | 5.3 | 0.4 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.6) | 15.8 (1.1) | 79** (1.3) |

| SSK retirees | 6553 | 12.9 | 0.4 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.4) | 18.9 (0.9) | 75.6** (1.0) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 1598 | 3.1 | 0.6 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.7) | 20.6 (1.6) | 74.2** (1.8) |

| Green Card | 4050 | 8 | 0.8 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.5) | 16.6 (1.1) | 77.1** (1.3) |

| Uninsured | 16161 | 31.8 | 0.2 (0.0) | 4.1 (0.3) | 12.9 (0.6) | 82.7** (0.8) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey.

Notes:

Total population for self reported health status (51 million) is less than our nonelderly total population (which is 66 million), due to missing values,

[*] Difference from the reference category (active civil servants) is significant at 1 [5]% level.

Sensitivity Analyses

We have tested the robustness of our results on burdens by insurance status (Table 1) to four alternative specifications. Appendix 1 presents our results when we add imputed rent for homeowners to income to define capacity to pay. Appendix 2 presents our results when we use total expenditures instead of income to define capacity to pay. Appendix 3 presents our results when we include the elderly (age 65 and over) in our sample population.

In all these cases, the prevalence of burdens are virtually identical for the whole population and are very similar by insurance status. The rankings of the different insurance schemes in terms of prevalence of high burdens are robust to these alternative specifications.

Furthermore, we have run the burdens excluding the households with zero-recorded income in order to see if replacing their income with the minimum wage has impacted our results. Again, it is observed that the rankings of the different insurance schemes in terms of prevalence of high burdens are robust (Appendix 4).

Discussion

In this study, we examined whether and to what extent the health insurance system in Turkey provided adequate protection against high out of pocket expenditures in the period prior to “The Health Transformation Programme” (HTP) for the non-elderly population. Financial burden of the Turkish health system has never been questioned for the period before the HTP period. One of the main reason is that researchers have not an opportunity to access the National Household Health Expenditure Survey 2002–2003 which has been conducted as part of Turkish Ministry of Heath’s effort to develop and implement ‘National Health Accounts’ that are in line with the standards of European Union and OECD Health Accounts System. Our study is the first to use the 2002/03 National Household Health Expenditure Survey data in order to analyze financial burden of health care expenditure. The National Household Health Expenditure Survey is specifically designed to collect health related expenditures as well as detailed information on health utilization and health status.

We found that 18.9% of the nonelderly population were living in families spending more than 10% of family income on health care and 14.4% of the nonelderly population were living in families spending more than 20% of family income on health care. Furthermore, those with lower income, those living in rural area, those living in the eastern region, those living in Istanbul and those who are younger have greater risk of having high out of pocket burdens. More significantly, we find that the risk of high financial burden varied among the five separate public schemes that provided health insurance in the pre-reform period. We also find wide variation in terms of access to care and self-reported health status between the different insurance schemes.18

There are some limitations of the high burden measures. Some household could have registered spending zero % of their income on health precisely because they were too poor to access care. We found that 1.5% of households were dissuaded from seeking health care because of out-of-pocket payments. In addition, 0.7% of families incurred loss of income from an inability to work.

In literature there are three main studies that examine financial burden of health expenditures in Turkey during the HTP period: (3), (16) and (17). All of these studies employ the Household Budget Surveys. The first study considers healthcare expenditures for the years 2003, before the reforms, and 2006, after the reforms (3). Its results show that with the reforms ratio of households with non-zero OOP expenditure has increased, but the share and level of OOP expenditures have decreased. There is another study which employs the Household Budget Survey 2006 and defines expenditures as catastrophic if they exceed 40% of income remaining after subsistence needs have been met (16). It found that the proportion of households with catastrophic health expenditure is 0.6% and impoverished households consist 0.4% of total. Their study does not provide quantitative comparison with the pre-reform system in Turkey since it only considers the 2006 data, but concludes that Turkish population, on average, has better protection from catastrophic medical expenses than in many other countries with comparable income levels at that time (16).

The forthcoming World Bank study considers health expenditure burdens in Turkey by employing the Household Budget Survey 2006 (17). It found that only 5.3% of households were spending more than 10% of their household expenditure on health care in 2006. These estimates are significantly lower than ours, suggesting that financial burdens of medical expenses are lower after the HTP period. This may indicate that the health system reforms were successful in providing the financial protection against high health expenses, since more people in Turkey benefited from risk pooling health insurance (1, 2, 5).

This paper fills a gap in providing analyses of health care expenditures from a non-developed country. Turkey is of particular interest because it is what the UN calls an “upper middle income developing” country that has a long history of European ties and alignment and is currently engaged in widespread health reforms. Our study provides the baseline against which policymakers can measure the success of the Turkish health care reform in terms of the affordability of health care and financial protection. Indeed, our method may also guide other developing countries in measuring affordability of health care within their health care systems.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, Informed Consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Strategy Development Headship of the Turkish Ministry of Health (MoH) for sponsoring Seher Nur Sulku’s visit to US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This study has been completed as a project of AHRQ titled as ‘Project of Financial Burden of HealthCare’, Project No: IM07266, 2008–2009. We thank the MoH Turkey Turkish Institute of Health (TUSAK) for providing access to the 2002–2003 National Household Health Expenditure Survey data and TUSAK specialists for technical assistance. We are grateful to Steve Cohen, Director of the Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends (CFACT), AHRQ, Jessica Banthin, Director of the Division of Modeling and Simulation, CFACT, AHRQ, and Joel Cohen, Director of the Division for Economic and Social Studies, CFACT, AHRQ, for helpful comments. Any remaining errors are our own. All the views expressed in this paper belong to the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the MoH, TUSAK or AHRQ.

Appendix 1:

Components of family out-of-pocket burdens, Turkey, 2002–2003 Age <65, imputed rent is added to income for homeowners

| Insurance Status | Population (*1000) | Family Income (US $)† | Out-of-pocket spending on care (US $)† | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 10 % | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 20 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turkey Sample | 63547 | 4433 (169.8) | 351 (21.9) | 17.4 (0.6) | 12.5 (0.6) |

| Active Civil Servants | 4948 | 6692 (485.6) | 215 (50.0) | 8.2 (1.1) | 5.3 (0.9) |

| SSK active | 14903 | 5024** (203.8) | 371* (61.0) | 14.7** (0.9) | 9.1** (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur active | 5237 | 6003 (944.2) | 385* (49.9) | 19.2** (1.7) | 13.7** (1.5) |

| GERF | 2860 | 5771 (220.1) | 213 (36.5) | 9.4 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.1) |

| SSK retirees | 6968 | 4562** (125.9) | 298 (43.3) | 13.5** (1.0) | 8.2* (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 1685 | 4339** (272.9) | 333 (93.5) | 15.4** (1.9) | 10.8** (1.7) |

| Green Card | 5421 | 2013** (107.9) | 282 (32.6) | 23.6** (1.7) | 18.3** (1.6) |

| Uninsured | 20928 | 3381** (196.0) | 422** (32.8) | 22.2** (1.1) | 17.5** (1.0) |

| Private Insurance | 273 | 13990** (2541.2) | 153 (53.3) | 5.5 (2.7) | 0.9** (0.7) |

| Others | 323 | 3768** (474.5) | 179 (53.1) | 12.9 (3.5) | 5.2 (2.1) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. Survey has been done in September 2002/ April 2003 period. Thus we employed average exchange rate of this period (1 US $ = 1.6 YTL) to convert family income and OOP spending on health into dollar terms.

Notes:

Standard errors of means are in parentheses.

Appendix 2:

Components of family out-of-pocket burdens, Turkey, 2002–2003 Total expenditure instead of income is used to define capacity to pay

| Insurance Status | Population (*1000) | Family Expenditure (US $)† | Out-of-pocket spending on care (US $)† | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 10 % | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 20 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turkey Sample | 66085 | 2856 (57.2) | 352 (21.9) | 17.1 (0.6) | 11.9 (0.5) |

| Active Civil Servants | 5150 | 3505 (176.3) | 209 (48.2) | 10.0 (1.2) | 5.8 (0.9) |

| SSK active | 15181 | 3089* (81.2) | 367* (59.9) | 15.4** (0.9) | 9.5** (0.7) |

| Bag-Kur active | 5562 | 3201 (131.8) | 388* (51.7) | 16.9** (1.5) | 12.0** (1.3) |

| GERF | 2899 | 3373 (150.2) | 211 (36.1) | 9.0 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.1) |

| SSK retirees | 7012 | 2879** (97.9) | 299 (43.1) | 14.9** (1.1) | 9.4** (0.9) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 1696 | 2622** (142.5) | 331 (93.0) | 17.7** (2.1) | 12.9** (1.9) |

| Green Card | 5752 | 2020** (115.9) | 286 (34.5) | 20.9** (1.6) | 15.3** (1.5) |

| Uninsured | 22239 | 2591** (62.4) | 424** (33.2) | 20.9** (1.0) | 15.7** (0.9) |

| Private Insurance | 273 | 5256* (711.4) | 153 (53.3) | 4.1 (2.1) | 1.6** (1.0) |

| Others | 323 | 2766* (271.8) | 179 (53.1) | 12.1 (3.4) | 8.0 (3.0) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. Survey has been done in September 2002/ April 2003 period. Thus we employed average exchange rate of this period (1 US $ = 1.6 YTL) to convert family expenditure and OOP spending on health into dollar terms.

Notes:

Standard errors of means are in parentheses. Statistical significance denotes difference from the reference category which is active civil servants.

P<0.05

P<0.01

Appendix 3:

Components of family out-of-pocket Burdens, Turkey, 2002–2003 Sample population includes elderly (age≥65) in addition to nonelderly (age<65) population

| Insurance Status | Population (*1000) | Family Income (US $)† | Out-of-pocket spending on care (US $)† | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 10 % | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 20 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turkey Sample | 70985 | 3864 (154.4) | 347 (21.2) | 18.7 (0.6) | 14.2 (0.6) |

| Active Civil Servants | 5250 | 6080 (458.8) | 207 (47.3) | 8.8 (1.1) | 5.7 (0.9) |

| SSK active | 15456 | 4545** (194.3) | 362* (58.8) | 15.8** (0.9) | 10.6** (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur active | 5671 | 5204 (877.4) | 387** (50.8) | 21.6** (1.6) | 16.9** (1.6) |

| GERF | 3644 | 5031* (198.7) | 237 (38.6) | 11.0 (1.2) | 7.1 (1.0) |

| SSK retirees | 8279 | 3964** (113.5) | 300 (41.6) | 14.8** (1.0) | 9.6** (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 2650 | 3760** (239.2) | 262 (61.0) | 15.8** (1.6) | 10.8** (1.3) |

| Green Card | 6086 | 1671** (98.8) | 298 (38.5) | 25.8** (1.8) | 22.2** (1.7) |

| Uninsured | 23281 | 2852** (179.0) | 421** (32.8) | 23.3** (1.0) | 19.3** (1.0) |

| Private Insurance | 282 | 13144** (2424.1) | 151 (51.9) | 5.7 (2.6) | 1.9** (1.1) |

| Others | 384 | 3174** (389.8) | 181 (47.1) | 15.7 (3.5) | 7.9 (2.4) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. Survey has been done in September 2002/ April 2003 period. Thus we employed average exchange rate of this period (1 US $ = 1.6 YTL) to convert family income and OOP spending on health into dollar terms.

Notes:

Standard errors of means are in parentheses. Statistical significance denotes difference from the reference category which is active civil servants.

P<0.05

P<0.01

Appendix 4:

Components of family out-of-pocket burdens, Turkey, 2002–2003 Sample population age <65, excluding families with zero income

| Insurance Status | Population (*1000) | Family Income (US $)† | Out-of-pocket spending on care (US $)† | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 10 % | Percent in families with out-of-pocket burden greater than 20 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turkey Sample | 59578 | 4332 (175.9) | 358 (23.1) | 17.8 (0.6) | 12.8 (0.6) |

| Active Civil Servants | 4885 | 6449 (489.1) | 218 (50.6) | 8.4 (1.2) | 5.2 (0.9) |

| SSK active | 14441 | 4809** (206.0) | 373 (62.9) | 15.0** (0.9) | 9.5** (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur active | 4568 | 6368 (1071.1) | 390* (53.4) | 19.0** (1.7) | 13.3** (1.5) |

| GERF | 2805 | 5358* (203.0) | 203 (35.7) | 9.7 (1.3) | 6.1 (1.1) |

| SSK retirees | 6783 | 4205** (124.3) | 296 (44.4) | 14.5** (1.1) | 8.9** (0.8) |

| Bag-Kur retirees | 1589 | 4041** (268.8) | 348 (99.0) | 16.6** (2.1) | 10.9** (1.6) |

| Green Card | 4861 | 1973** (110.4) | 307 (35.7) | 24.3** (1.9) | 20.2** (1.7) |

| Uninsured | 19117 | 3334** (211.5) | 437** (35.3) | 23.0** (1.2) | 18.2** (1.1) |

| Private Insurance | 257 | 14179** (2602.2) | 157 (55.8) | 5.1 (2.7) | 0.9** (0.7) |

| Others | 273 | 4003** (489.2) | 203 (62.1) | 14.9 (4.1) | 5.7 (2.4) |

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. Survey has been done in September 2002/ April 2003 period. Thus we employed average exchange rate of this period (1 US $ = 1.6 YTL) to convert family income and OOP spending on health into dollar terms.

Notes:

Standard errors of means are in parentheses. Statistical significance denotes difference from the reference category which is active civil servants.

P<0.05

P<0.01

Footnotes

For the percentage of the population under each insurance scheme please see Section 4 Results ‘Burdens by Insurance Status’ part of our study.

Additional sources of funding are payments of non-members for using SSK facilities (such as Bag-Kur members).

However, neither of the insurance schemes were charging for the long-term outpatient drug therapies for chronic illnesses such as cancer.

This amount was the multiplication of ‘civil servants wage multiplier’ by 20. Civil servants wage multiplier, which is a constant less than one, renewed in each 6 months by Council of Ministers.

Turkish Institute of Health (TUSAK), operating under the MoH Turkey, conducted National Health Accounts study with a consortium of Harvard Public Health School and Health Management Research Company. The consortium assigned BİGTAŞ research company to conduct the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey. The Survey’s sample has been developed and approved by the cooperation of Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK).

The sample chosen with random probability sample technique to represent Turkey’s population and its five regions. In fact Turkey is composed of 7 geographical regions: North (Karadeniz Region), South (Akdeniz Region), South East, Central Anatolia, East Anatolia, Aegean and Marmara Regions. However, this survey combines South East and East Anatolia regions as ‘East’; and combines Aegean and Marmara Regions as ‘West’.

The weights, constructed by Turkish Statsistical Institute (TUIK), are used.

In the methodology employed the expenditures by elderly members living in the household are included to calculate family level expenditures, but the results were presented at the person-level only for the population aged below 65.

The expenses for transportation, meal and hospital attendant are called as indirect expenses. In literature these expenses do not included directly in the OOPS on health.

The survey collected only premium for private insurance. Only 0.4% of non-elderly population is privately insured in Turkey in 2002–2003 (our calculation using data from the 2002–2003 National Household Health and Expenditure Survey). Thus we did not include the premium payments in the financial burden.

The survey gathers information about the use of health care services and what have spent on the use of these services in the last 6 months (the recall period is 6 months). The MoH have scaled these up to an annual basis by adding expenditures reported in the two waves. Annual family income is the sum of annual personal income of each family member. Annual personal income is composed of the sum of income received during last 12 months such as salary, wage or crop share, interest income, rental income, remittance, any payment from public aid programs in cash or in kind and inheritance (or lotteries in cash or in kind).

Yearly minimum wage was $1468.3 in 2002 and $1816.4 in 2003. Thus a weekly minimum wage is $30.5 in 2002 and $37.8 in 2003.

TUIK provides poverty lines for families composed of at most 10 persons. In our analyze families crowded than 10 persons constitutes 4% of our sample. Indeed, only 3% of them incurred health care expenses greater than 10% of family income. Thus, we did not consider families crowded than 10 persons, and this does not affect our results represented in this section.

Note that the size of the lower income groups is higher than the official estimates, but it is within the poverty estimates for Turkey. According to TUIK, 18.6 % of the population was below the poverty line. According to the World Bank, in 2003 29.6 of the population was below the poverty line. According to Ankara Business Bureau, 74 % of the population is below the poverty line. Underreporting of income in the household survey may also partially explain the discrepancy.

Other health coverages are mainly the abroad health insurances and the Turkish Armed Forces’ health insurance for soldiers and disabled because of war & their dependents.

In the health care system prior UHI if the parents did not protected by health insurance either their children were covered. When we consider the percentage of the population covered by any insurance according to age, we see that approximately 38% of juniors aged 0–17 were uninsured, while only 15,7% of the adults aged 55–64 were uninsured (our inspection, not shown in Table 3). Moreover when family income is taken into account, it is seen that 63,2% of juniors aged 0–17 were living in poor families, while relatively lower percentage (43,3%) of adults aged 55–64 were living in poor families.

It is observed that GERF provides the best financial protection against high out-of-pocket health spending, followed by SSK and Bag-Kur. Even though our study could not take into account the premium payment because of lack of data, we should emphasize that high premium payment requirement of Bag-Kur were causing its members to not regularly contribute the health care insurance program (which was not mandatory). Thus, even if person covered by Bag-Kur, she might not access its health insurance benefits.

References

- 1.MoH. Future for Turkish Health Sector Under 21 Aims (21 Hedefte Türkiye Sağlıkta Gelecek) Ministry of Health & Refik Saydam Hygiene Center School of Public Health Publication; Ankara, Turkey: 2007. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD. Reviews of Health Systems Turkey. OECD & the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, OECD publishing; France: 2009. pp. 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erus B, Aktakke N. Impact of healthcare reforms on out-of-pocket health expenditures in Turkey for public insures. European Journal of Health Economics. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD. Health Data 2008. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); Paris, France: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MoH. Health 2006. Ministry of Health Publication; Ankara, Turkey: 2006. pp. 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatar MH, Ozgen B, Sahin PB, Berman P. Informal payments in the health sector: a case study from Turkey. Health Affairs. 2007;26(4):1029–39. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Bank. Turkey: Reforming the Health Sector for Improved Access and Efficiency, Volume 1. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; Washington DC: 2003. pp. 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Social Security Institution. Activity report (2007 yılı faaliyet raporu) Social Security Institution; Ankara, Turkey: 2007. Available from http://www.sgk.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/2c3544004c1667138480846156da2d6a/2007FaaliyetRaporu.pdf?MOD=AJPERES. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. The Lancet. 2003;362:111–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Than NBT, Lofgren CI. Household out-of-pocket payments for illness: evidence from Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somkotra T, Lagrada LP. Which households are at risk of catastrophic health spending: experience in Thailand after universal coverage. Health Affairs. 2009;28(3):w467–w478. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296(22):2712–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banthin JS, Cunningham P, Bernard DM. Financial burden of health care, 2001–2004. Health Affairs. 2008;27(1):188–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard D, Banthin J, Encinosa W. Health care expenditure burdens among people with diabetes in 2001. Medical Care. 2006;44(3):210–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199729.25503.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernard D, Banthin J. Medicare Part D and health care expenditure burdens among the elderly: 2005 & 2007. Health Affairs 2010 Under review at. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yardim MS, Cilingiroglu N, Yardim N. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Turkey. Health Policy. 2010;94(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aran M, Hentschel J. Household level health expenditures and health insurance coverage of the poor in Turkey. Washington DC: World Bank; (Forthcoming) [Google Scholar]