Abstract

Background:

To determine the prevalence and characteristics of birth defects in perinatal infants in Hubei Province during 200l–2008.

Methods:

The prevalence of birth defects in perinatal infants delivered after 28 weeks or more was analyzed in Hubei surveillance hospitals during 200l–2008.

Results:

The incidence of birth defects in perinatal infants from 200l to 2008 was 120.0 per 10,000 births, and was increased by about 41% from 81. 1 in 2001 to 138.5 per 10,000 births in 2008. The incidence in the first 4 years (2005–2008) was much higher than the latter four (2001–2004) (χ2=77.64, P <0.05). The difference in prevalence between urban and rural was of no significance in 2008 (χ2=0.03, P >0.05), but that between male and female was significant (χ2=5.24, P <0.05), as the former prevalence was much higher. The prevalence of birth defects was slightly higher among mothers over 35 years old than those under 35 years old, but with no significance (χ2=1.98, P >0.05). The two leading birth defects were cleft lip and/or palate and polydactyly, followed by congenital heart disease, hydrocephaly, external ear malformation and neural tube defects. The prevalence of congenital heart disease was rising.

Conclusions:

Eight years’ birth defects data indicate that the birth defect rate was on the rise and the birth defects prevalence in Hubei province should be valued.

Keywords: Birth defect, Prevalence, Perinatal infants, Surveillance, Prevention

Introduction

Birth defect (BD) is a widely used term for a congenital malformation; it involves the abnormality in morphology, structure, function, metabolism, psychology and behavior. With more epidemics prevented and controlled, it has gradually become the main cause of infant and child mortality. China is one of the countries with high incidence of BD, with 800,000 to 1.2 million infants born with BD and disabilities annually, accounting for four to six percent of the country’s total newborn. The Chinese government has established a surveillance system for monitoring BD since 1986. Twenty-three types of BDs were included in the system according to the International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification Codes, tenth edition (i.e., ICD-10). In this research, we analyzed the prevalence and characteristics of BD in perinatal infants in Hubei province (Central China) during 200l–2008, in order to provide a scientific basis for developing control measures over prevention of BD on perinatal infants.

Materials and Methods

The perinatal infants presented for this report pertained to all cases (livebirths, fetal deaths, or stillbirths after 28 weeks of gestation and terminations of pregnancy for fetal anomaly; accessing within 7 days after delivery) of congenital anomaly from 52 surveillance hospitals in Hubei province between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2008.

Under the guideline of ICD-10, which delineates twenty-three different types of BDs, all infants were examined carefully by specialized doctors using routine obstetric diagnosis, physical examination or autopsies and a “BD registration card” would be filled, and reported through the network.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 12.0, Chicago, IL) for the analysis of BD incidence. The Chi-squire test was done for the determination of statistical significance.

Results

Overall BD prevalence

69,408 infants were covered in 52 surveillance hospitals in 2008 and 961 infants were found to have BDs, making the prevalence 13.85‰, which exceeded the last 7 years’. Besides, the prevalence of the first 4 years (2005–2008) was much higher than the latter four (2001–2004) (χ2=77.64, P <0.05).

BD prevalence in different infants’ groups

We analyzed the prevalence of infants classified to residence, gender and maternal age in 2008. The difference of prevalence between urban and rural was of no significance (χ2=0.03, P >0.05), but that between male and female was significant (χ2=5.24, P <0.05), as the former prevalence was much higher. The prevalence was slightly higher among mothers over 35 years old than those under 35 years old, but with no significance (χ2=1.98, P >0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Prevalence of BD by different characteristics of infants in 2008, Hubei Province

| Characteristic variable | Number of BDs † | Total births | Total prevalence per 10,000 births (95% CI†) | χ2 value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 589 | 42,342 | 139.1 (127.9 to 150.3) | 0.03 | 0.855 |

| Suburb | 372 | 27,066 | 137.4 (123.6 to 151.3) | ||

| Sex of infant | |||||

| Male | 542 | 37,566 | 144.3 (132.2 to 156.3) | 5.24 | 0.022* |

| Female | 395 | 31,818 | 124.1 (112 to 136.3) | ||

| Unclear‡ | 24 | 24 | – | ||

| Maternal age, y | |||||

| <20 | 14 | 1,004 | 139.4 (67 to 212) | 5.69 | 0.224 |

| 20- | 336 | 22,583 | 148.8 (133 to 164.6) | ||

| 25- | 380 | 29,146 | 130.4 (117.4 to 143.4) | ||

| 30- | 157 | 12,106 | 129.7 (109.5 to 149.9) | ||

| 35- | 74 | 4,569 | 162 (125.4 to 198.6) | 1.98 | 0.160 |

P<0.05 (significant difference).

BDs, birth defects; CI, confidence interval

When compared unclear group did not included.

Top six BDs and prevalence

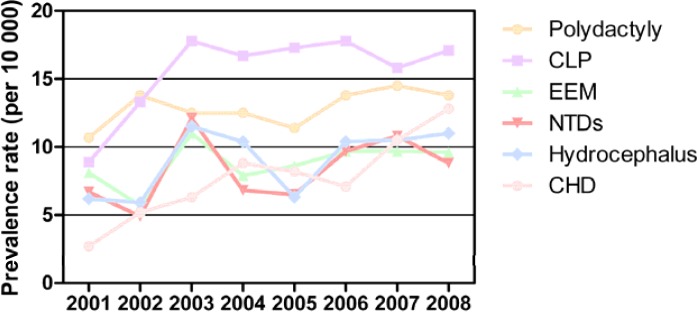

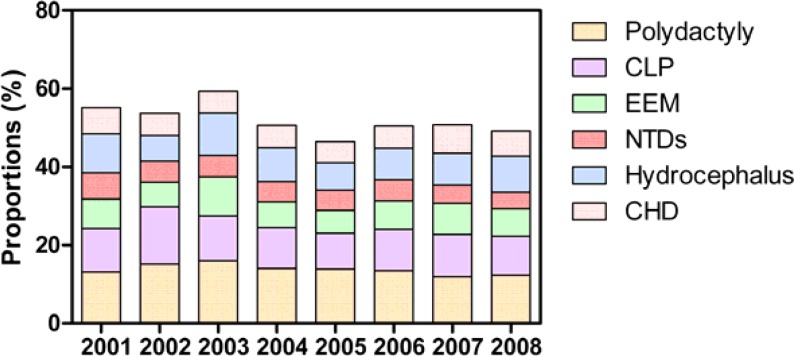

The two leading BDs were cleft lip and/or palate (CLP, without cleft palate) and polydactyly during 2001–2008; the prevalence fluctuated around 1.7 ‰ and 1.3‰ respectively. In 2008, congenital heart defect (CHD), hydrocephaly, external ear malformation (EEM) and neural tube defects (NTDs, including anencephalia, rachischisis and encephalocele) followed the top two BDs. The above top six BDs constituted over the half of all BDs in 2008, with a much higher level (64%) in 2003. The prevalence of CHD was rising from top nine in 2001 to top three in 2008, as 0.27‰ to 1.28‰. However, the prevalence of NTDs was decreased sharply in 2008. (Fig.1 and 2)

Fig.1:

Prevalence of top 6 BDs during 2001–2008 in Hubei province. BDs, birth defects; CLP,cleft lip and/or palate; EEM,external ear malformation; NTDs, neural tube defects; CHD, congenital heart defect

Fig. 2:

Proportions of top 6 BDs during 2001–2008 in Hubei province. BDs, birth defects; CLP,cleft lip and/or palate; EEM,external ear malformation; NTDs, neural tube defects; CHD, congenital heart defect

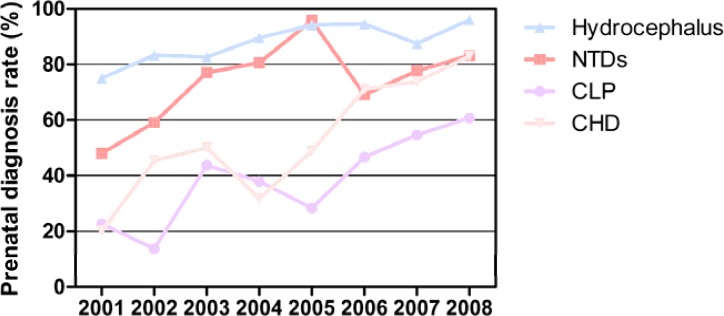

Prenatal diagnosis of BD

In general, prenatal diagnosis rate of BD was increased, such as CHD, as its rate was increased to 82.95% in 2008 from 20% in 2001. (Fig.3)

Fig. 3:

Prenatal diagnosis rate of BD during 2001–2008 in Hubei province.BD, birth defect; NTDs, neural tube defects; CLP,cleft lip and/or palate; CHD, congenital heart defect

Quality control

Department of Public Health spot-checked nine cities and seventeen counties in 2008, finding that the rate of missing report of surveillance hospitals was 15.72%.

Discussion

Chinese government has started BD surveillance since mid 80s. Since 1986, surveillance system of Hubei province had been growing steadily till 2001. Fifty-two surveillance hospitals were included in 2001 and the number of infants under surveillance was nearly 40,000 each year, which made the data reliable. During 2001–2008, 406,264 infants were covered and the BD prevalence was 12‰ (4,874 of 406,264), far exceeding the earlier prevalence (8‰) during 1997–2002 (1). The prevalence of 2008 was 13.85‰, a little higher than the national average prevalence (13.49‰). The data indicated an increase of BD prevalence, the same trend as the whole nation (2). To speculate, it may relate to several things. First, surveillance system was improved to make the data more genuine, especially with the advanced prenatal diagnostic techniques and expertise skills. Second, as the forcible premarital health assessment was cancelled, the risks of BD were increased. Furthermore, as modernization of the city, pollution and other modern life-related risks and lifestyle (e.g. delayed childbearing) (3) were responsible too.

The prevalence in urban and rural were of no significant difference in 2008, different from the earlier data published before 2008 which indicated that prevalence in rural was a little higher than in urban (1). The enhanced maternal and child health care in rural may contribute to the offset. The difference of prevalence between male and female was significant; the former prevalence was much higher, which paralleled with the data previously published (4). Advanced maternal age (over 35 years old) was related to a higher BD prevalence, but with no significance compared to the younger group, different from a majority of the data previously published (4, 5). The recent emphasis on the antenatal care and prenatal screening for pregnant women over 35 years old might be partly related to this difference.

From 2002 to 2008, CLP and polydactyly were continuously on top two. This may relate to genetic and environmental factors. Genetic factors contributing to CLP have been identified for some syndromic cases and many genes associated with syndromic cases of CLP have also been identified to contribute to the incidence of isolated cases of CLP (6). Besides, CLP and other congenital abnormalities have been linked to maternal hypoxia, as caused by e.g. maternal smoking (7–9), maternal alcohol abuse or some forms of maternal hypertension treatment (10). Integration of genetic and environmental risk using different methods may generate a synthesis that will both better characterize etiologies, as well as provide access to better clinical care and prevention (11). A case-control study by JY Luo, et al. (12) on polydactyly showed that heredity was the foremost risk factor. At the same time, CHD was growing year after year, ranking top three in 2008, which was partly due to improved prenatal diagnostic techniques and skills and increased environmental risks. With above three BDs, hydrocephaly, EEM and NTDs were still the main BDs and constituted over 50% of all BDs, while shooting up to 64% in 2003 probably due to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, which made hospitals screening for BD in a much more cautious way.

The top six BDs in Hubei province were similar to national data, but their prevalences were all higher than national average ones except CHD (2). Data published on Annual Report of the National Maternal and Child Health Care Surveillance and Communications in June, 2009 indicated that the prenatal diagnosis rate in Hubei province in 2008 was 14.29%, a bit lower than eastern coastal cities and provinces. All the data showed that there was more the maternal and child health care could do to improve the present situation. As periconceptional folate supplementation has a strong protective effect against NTDs (13), pregnant woman has been encouraged to take folic acid supplements to prevent NTDs by doctors. Actually, the decrease of NTDs did happen which was owe mainly to the folic acid supplements taking measure (14). To reduce the overall prevalence of BD, it is necessary to keep the surveillance system function properly and provide prevention and health care service extensively. To reduce the rate of missing report of surveillance hospitals and make the BD data much more convenient and accessible, it is of help to draw lessons from the European network of registers for the epidemiologic surveillance of congenital anomalies, the EUROCAT (15). Besides, primitive maternal and child health care service should be easily approachable for women of childbearing age, especially those living in rural areas (16). Furthermore, studies on the integration of genetic and environmental risks, especially the links between environmental geochemistry and prevalence of BD (17), are also important for better characterizing etiologies, as well as providing access to better clinical care and prevention.

Eight years’ BD data indicate that the BD prevalence was rising and the BD prevalence in Hubei province should be valued; prevention program of BD shall be better performed to decrease prevalence of birth deformation in perinatal infants based on improved perinatal care and prenatal diagnosis.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, Informed Consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all staff members involved in birth defects monitoring in Hubei province and the China Birth Defect Monitoring Center. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Gong LY, Mao ZF, Li XD. Analysis of birth defects in 1997–2002 in Hubei Province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2004;25(10):881. (in chi). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MCHSCN Annual Report of the National Maternal and Child Health Care Surveillance and Communications. 2010. Available from: www.mchscn.org.

- 3.Griffiths SM. Leading a healthy lifestyle: the challenges for China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(3 Suppl):110S–116S. doi: 10.1177/1010539510373000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou LQ, Li XD. Analysis of Surveillance of Birth Defect on Perinatal Fetuses in Hubei Province during 2001–2005. J Applied Clinical Pediatrics. 2007;22(11) (in chi). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou AF, Qin LZ, Zhang YM. Analysis of the report of perinatal birth defects monitoring in Wuhan city from 2004 to 2007. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2008;23(24) (in chi). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacqueline QYSHB, Hechta T. Genetic Causes of Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip with or without Cleft Palate. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;70:107–113. doi: 10.1159/000322486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B, Jiao X, Mao L, Xue J. Maternal cigarette smoking and the associated risk of having a child with orofacial clefts in China: A case-control study. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;39(5):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi M, Wehby GL, Murray JC. Review on genetic variants and maternal smoking in the etiology of oral clefts and other birth defects. Birth defects research. Part C, Embryo today: reviews. 2008;84(1):16. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little J, Cardy A, Munger RG. Tobacco smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(3):213–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurst J, Houlston R, Roberts A, Gould S, Tingey W. Transverse limb deficiency, facial clefting and hypoxic renal damage: an association with treatment of maternal hypertension? Clinical Dysmorphology. 1995;4(4):359. doi: 10.1097/00019605-199510000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12(3):167–178. doi: 10.1038/nrg2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo JY, Fu CH, Yao KB, Hu RS, Du OY, Liu ZY. A case-control study on genetic and environmental factors regarding polydactyly and syndactyly. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2009;30(9):903. (in chi). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry RJ, Li Z, Erickson JD, Li S, Moore CA, Wang H, Mulinare J, Zhao P, Wong LY, Gindler J, Hong SX, Correa A. Prevention of neural-tube defects with folic acid in China. China-U.S. Collaborative Project for Neural Tube Defect Prevention. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(20):1485–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911113412001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu L, Ling H. National Neural Tube Defects Prevention Program in China. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S196–204. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd PA, Haeusler M, Barisic I, Loane M, Garne E, Dolk H. Paper 1: The EUROCAT network--organization and processes. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2011;91(Suppl(1)):S2–15. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han Y, Wei J, Song X, Sarah BJ, Wen C, Zheng X. Accessibility of Primary Health Care Workforce in Rural China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011 2011 Apr 13; doi: 10.1177/1010539511403801. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu HY, Zhang KL. Links between environmental geochemistry and rate of birth defects: Shanxi Province, China. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409(3):447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]