Abstract

Background:

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the inequality of geographical distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds in Iran using the Gini coefficient.

Methods:

The population information of Iran’s provinces in 2006 was obtained from The Statistical Center of Iran and the number of non-cardiac intensive care beds (including ICU, PostICU and NICU beds) in all provinces was taken from published information of Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran in the current year. The number of beds per 100,000 populations of each province and the Gini coefficients for each bed were calculated.

Results:

Iran’s population was 70,495,782. The total number of ICU, PostICU and NICU beds were 3720, 291 and 1129, respectively. Tehran had the highest percentage of each bed among all provinces. The number of each bed was 5.3, 0.4 and 1.6 per 100,000 populations of country, respectively. The calculated Gini coefficients for each bed were 0.17, 0.15 and 0.23, respectively.

Conclusion:

The findings of this study showed that, according to the Gini coefficients, non-cardiac intensive care beds have an almost equal geographical distribution throughout the country. However, the numbers of beds per population are less than other countries. Since such studies can be used as a base for health systems planning about correction of inequality of health services distribution, similar studies in other health care services are recommended which can be conducted at the national or provincial level.

Keywords: Intensive care beds, Geographical distribution, Inequity, Gini coefficient, Iran

Introduction

Inequality in health services distribution has become a worldwide challenge among different countries (1). From the viewpoint of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), health inequality in various countries has a progressive trend (2). Therefore, equality in distribution of health services and equal accessibility to such services has become a major principle in most health systems (3). Nevertheless, measuring equality in health is not a straightforward task. Different countries use different methods for such a purpose. In most countries, in fact, customer reports or policy makers' views are taken as defining criteria for equality and only few countries apply scientific and precise measures to quantify health care equality (4). In the U.S., in most cases equality in health is concerned with racial or ethnical differences (3). Some studies have even placed an emphasis on the regional changes in receiving equality in healthcare (5–7). Therefore, understanding the geographical distribution of health resources, equal accessibility to such resources and improvement of them may lead to better planning to make health services accessible by all (3).

Although the reasons for health services distribution are mentioned as unknown (8, 9), studies show that different factors such as personal, social, economic and geographical have some effect on health (10, 11). These factors are more obvious in developed and developing countries (12) as far as geographical distribution of health services in countries become a basic problem. On the other hand, the extent to which these factors make impact differs in various countries and even in various geographical areas within a country (11).

Intensive health care services have dramatically increased in the past decades. In fact, in 1985–2000 the percentage of intensive care units beds in the U.S. increased by 71.8%. In England and Wales, averages of 1% of hospital beds are especially used for intensive care, which counts as a dramatic disparity between different hospitals (13). In addition, European healthcare standards (as of 1994) require a 2–3% intensive care beds proportion (14). However, the ratio of ICU beds in 2007 in the U.S. was 2.8 to 10,000 population (from 1.01 to 5.95), which shows a marked and uneven distribution of healthcare resources across the country (15).

One of the most important indices of inequality of health services is the assessment of accessibility to the hospital intensive care services (16) and it is shown that people who have less ease of access to these cares also have lower health level (17). Since inhabitants in regions with lower hospital beds have lower health levels (18), assessment of the number and type of intensive care beds and their distribution can be used as an indirect method for assessment of the level of accessibility to the hospital intensive cares. However, there is a lack of information about the geographical distribution of intensive care beds in developing countries (19).

The Gini coefficient, which is based on and calculated from Lorenz curve, is a method for the evaluation of the equal distribution of health care services. This index compares the cumulative frequency curve of distribution of a variable with the equal distribution of it (20, 21). This index has been used in many medical studies such as survival studies (22), prediction of improvement rate (23), the number of Primary Care Physicians (24) and the number of hospital beds (3).

Since we have no data about the geographical distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds in our country, this study was conducted with the aim of assessment of the inequality of the geographical distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds (ICU, PostICU and NICU beds) in Iran by Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient.

Materials and Methods

In this study, the population data of Iranian provinces based on the latest population census in 2006 conducted by the Statistics Center of Iran was used. The number of non-cardiac intensive care beds (ICU, PostICU and NICU beds) in each province in 2006 was based on the latest published information of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran.

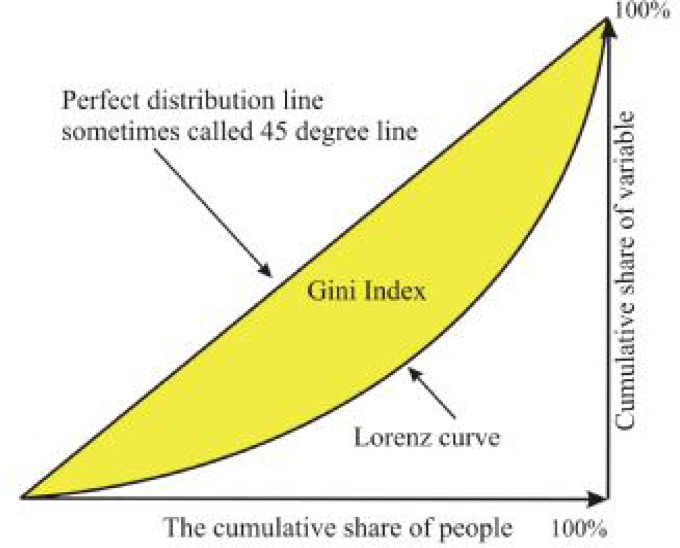

The Lorenz curve compares the distribution of a given variable with the uniform distribution (of same variable) that represents equality. This uniform distribution is shown by a diagonal line, the egalitarian line (25). The farther the Lorenz curve lies from this line, the higher the inequality (26) (Fig. 1). In this curve, horizontal axis (X) represents the cumulative percentage of population and vertical axis (Y) illustrates the percentage of some value held by the corresponding cumulative proportion of the population (26). In our study, the X axis illustrates the cumulative percentage of population of Iran’s provinces and the Y axis shows the cumulative percentage of each type of non-cardiac intensive care beds in Iran’s provinces.

Fig. 1:

In Lorenz curve cumulative percent of population is illustrated on horizontal axis while cumulative percent of other variable is figurate on vertical axis

The Gini coefficient is calculated as a proportion of two areas, the area of the egalitarian triangle as the denominator and the area between the Lorenz curve and the egalitarian line as the numerator (18). Its mathematical formula is as follows:

Or

In this study, X was the cumulative percentage of the population and Y was the cumulative percentage of each type of non-cardiac intensive care beds. The Gini coefficient ranges between 0 and 1, where theoretically, zero corresponds to a perfect equality and 1 corresponds to a perfect inequality. However, practically, a Gini coefficient smaller than 0.2 means an absolute equality; values between 0.2 and 0.3 indicate a high equality; between 0.3 and 0.4, an inequality; between 0.4 and 0.6, a high inequality; and greater than 0.6, an absolute inequality (27).

Population data and the number of non-cardiac intensive care beds of all provinces were entered into Excel software. The number of each intensive care beds per 100,000 populations and cumulative number of them was calculated for each province and with Lorenz curve, the Gini coefficient via above formula was computed for each bed type.

Results

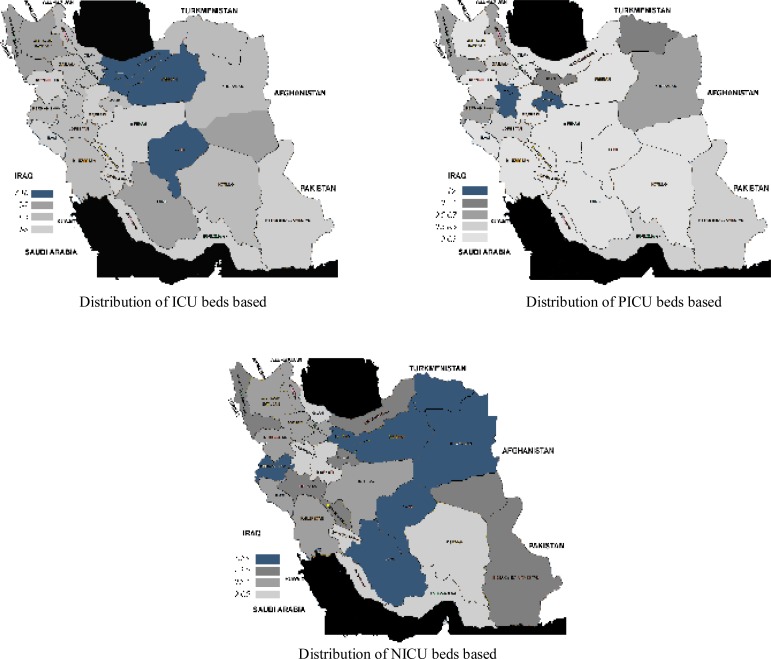

The total population of Iran was 70,495,782 in 2006 and the total numbers of ICU, PostICU and NICU beds in this year were 3720, 291 and 1129, respectively. Tehran had the highest percentage of each bed among all provinces. The number of these beds per 100,000 populations in the country was 5.3, 0.4 and 1.6, respectively. Table 1 shows country population, the number and percentage of ICU, PostICU and NICU beds and the number of beds per 100,000 populations according to the population of each province. Fig. 2 illustrates the geographical distribution of each bed on the map by province.

Table 1:

Iran population, the number and percentage of non-cardiac intensive care beds and beds number per 100.000 population in each province

| Province | Population (person) | ICU beds | Post-ICU beds | NICU beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Count | % | Count/100.000 Population | Count | % | Count/100.000 Population | Count | % | Count/100.000 Population | ||

| Ilam | 545,787 | 9 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Semnan | 589,742 | 51 | 1.4 | 8.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| Kohkiluyeh o Buyer Ahmad | 634,299 | 13 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| South Khorasan | 636,420 | 40 | 1.1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| North Khorasan | 811,572 | 27 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 6 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 20 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| Chahar Mahal o Bakhtyari | 857,910 | 21 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 10 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Bushehr | 886,267 | 24 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Zanjan | 964,601 | 32 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Yazd | 990,818 | 78 | 2.1 | 7.9 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 20 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Qom | 1,046,737 | 47 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 22 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 15 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Qazvin | 1,143,200 | 35 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Ardebil | 1,228,155 | 51 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 8 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Markazi | 1,351,257 | 30 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Hormozgan | 1,403,674 | 35 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 6 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Kurdestan | 1,440,156 | 38 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Golestan | 1,617,087 | 50 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 17 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Hamedan | 1,703,267 | 65 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 18 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 7 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Lorestan | 1,716,527 | 53 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 6 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 20 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Kermanshah | 1,879,385 | 90 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 10 | 3.4 | 0.5 | 54 | 4.8 | 2.9 |

| Gilan | 2,404,861 | 80 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Sistan o baluchestan | 2,405,742 | 68 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 8 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 25 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| Kerman | 2,652,413 | 92 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| West Azarbayjan | 2,873,459 | 170 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 18 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 36 | 3.2 | 1.3 |

| Mazandaran | 2,922,432 | 179 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 6 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 42 | 3.7 | 1.4 |

| East Azarbayjan | 3,603,456 | 222 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 7 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 32 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Khuzestan | 4,274,979 | 206 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 37 | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| Fars | 4,336,878 | 299 | 8.0 | 6.9 | 8 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 110 | 9.7 | 2.5 |

| Isfahan | 4,559,256 | 124 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 26 | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Khorasan Razavi | 5,593,079 | 238 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 34 | 11.7 | 0.6 | 221 | 19.6 | 4.0 |

| Tehran | 13,422,366 | 1,253 | 33.7 | 9.3 | 114 | 39.2 | 0.8 | 346 | 30.6 | 2.6 |

| Total | 70,495,782 | 3,720 | 100.0 | 5.3 | 291 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 1,129 | 100.0 | 1.6 |

Fig. 2:

Distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds based on beds number per 100.000 populations in each province of Iran

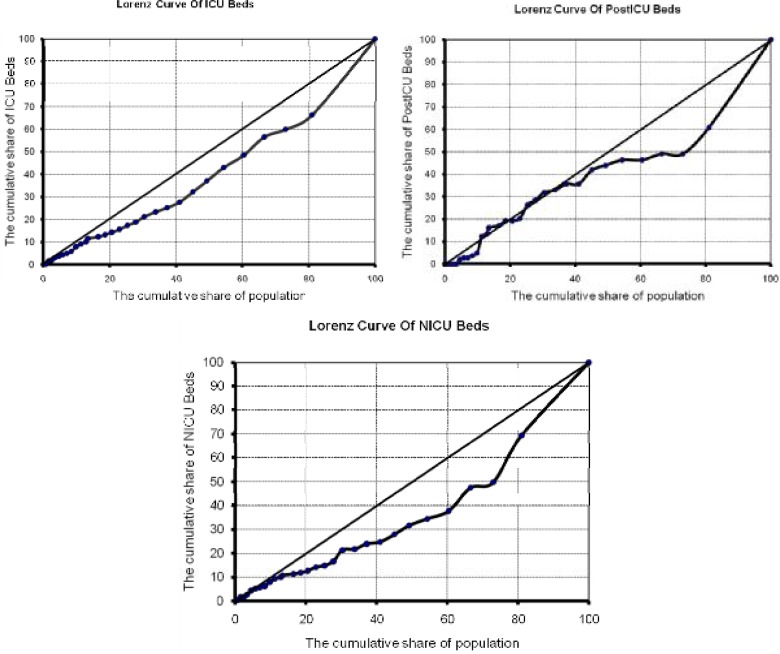

With the cumulative percentage of population and cumulative percentage of each bed, the Lorenz curves were drawn as shown in Fig. 3. The Gini coefficient for ICU, PostICU and NICU beds were calculated as 0.17, 0.15 and 0.23, respectively.

Fig. 3:

Lorenz curve of non-cardiac intensive care beds

Discussion

The findings of the present study show that the Gini coefficient for the ICU and PostICU beds in Iran is less than 0.2 and for NICU beds it is slightly more; thus it seems that the ICU and PostICU beds have more equal distribution than NICU ones. However, in spite of the slight difference, it can be assumed that the distribution of all non-cardiac intensive care beds based on Gini coefficient is equal throughout the country.

In this study, the numbers of ICU, PostICU and NICU beds per 100,000 populations in the country were 5.3, 0.4 and 1.6, respectively. The proportion of ICU beds per 100,000 people in 2005 were as varied as follows: 20 in the U.S., 9.3 in France, 13.5 in Canada, 24.6 in Germany, 3.5 in England, 21.9 in Belgium, 8.4 in the Netherlands and 8.2 in Spain (28). In South Africa, there were 4,168 ICU beds counted in 2005 of which 86% were installed in three provinces. The proportion of bed varied greatly in different provinces of this country, from 1:20,000 to 1:80,000 (19). The distribution of secondary and tertiary health services in the Palestine is also reported to be unequal, mostly concentrated in the downtown. In the Gaza Strip and in the Eastern Strip the proportions of IU beds per 1,000 were 1.4 and 1.2, respectively (29). Although there is a great difference between statistics of ours with developed countries and we are far from the ideal point, factors such as defined criteria for intensive care beds and its measurement, consideration of private hospital beds, neonatal beds, psychological beds and other intensive care beds may be causes accounting for this difference (30).

The Gini coefficient was used in a study in the U.S. in 1998 to measure the distribution of hospital beds. The findings showed coefficients of 0.0571–0.4303 in different states (3). The 1970–1997 trend indicated progressive equality in the distribution of hospital beds. The northern states have been reported to enjoy an equal distribution of hospital beds (3). Although the obtained Gini coefficients in our study are representative of equality distribution of these beds throughout the country, the geographical distribution of each bed may be different among various provinces and the centers of each province may have higher number of intensive care beds than other areas. Among all provinces, in Tehran, the capital of Iran, the ratios of all beds were almost two times higher than other provinces. In addition, it must be considered that, although the Gini coefficient of Post ICU beds was almost equal to the ICU beds, the number of such beds in some provinces was zero.

Overall, past studies about health status throughout the country showed that Isfahan, Tehran and Markazi provinces had ideal health status, while Ardebil, Golestan and Qom provinces did not have an appropriate health status and the health status of Khuzestan, Sistan Baluchestan and Kohkiluyeh Buyer Ahmad were very poor (31). Studies in some countries such as England (32), Turkey (17), Italy (33), Australia (30) and the USA (34) have shown that inhabitants of rural areas or in vicinity of big cities have lower levels of accessibility to intensive cares. Moreover, these people are in lower socioeconomical status and consequently in lower health status. Because of centralization policies especially in developing world, the population around big cities may become higher and higher, thus the need for all types of hospital beds, especially intensive care beds, will increase dramatically (35).

In addition, it must considered that merely the number of intensive care beds cannot be a representative of appropriate use of them and other factors such as coordination between prehospital emergency cares and hospitals, accurate programming for better use of intensive care units, presence of a intensive care specialists, presence of complete treatment guidelines, good nutritional support for patients of these wards and training of family members of patients for co-operation with treatment personnel can lead to the appropriate use of these facilities.

This study is the first one in the field of assessment of inequality of geographical distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds in Iran in which each type of bed was evaluated separately. However, it must be noted that, this study was a cross sectional one and conducted in 2006. In addition, the distribution of beds was assessed throughout the country not in each province separately due to lack of information sources from the geographical distribution of beds in each province. However, the findings of this study can be used by managers and policy makers of health system for planning to abolish inequality in distribution of health care services alongside other indices. Therefore, such studies which should be done continuously and use of indices about all types of health care services which represent inequality in their distribution, such as Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient, could lead to a better understanding and consequently planning for improvement of quality of services.

In conclusion, this study showed that, according to the Gini coefficients, geographical distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds did not differ significantly and all of them, especially ICU and PostICU beds, had equal geographical distribution throughout the country. However, some provinces had no PostICU beds. In addition, except Tehran, there are little differences among other provinces. Such studies can be used as a base for health systems planning to correct inequality of health services distribution. Therefore, similar studies in all health care services should be carried out at national or provincial levels for obtaining more data.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical issues including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc. have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Statistics Center of Iran and the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran for their kind cooperation. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, et al. European Union Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2468–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Social determinants of health. 2011. Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Available from: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en (Accessed 14th February 2011)

- 3.Horev T, Pesis-Katz I, Mukamel DB. Trends in geographic disparities in allocation of health care resources in the US. Health Policy. 2004;68(2):223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Doorsalaer E, Wagstaff A, Rutten F. Equity in the finance and delivery of health care: an international perspective, Commission of the European Communities health services research series, No 8. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cable G. Income, race, and preventable hospitalizations: a small area analysis in New Jersey. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002;13(1):66–80. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller ME, Holahan J, Welch WP. Geographic variations in physician service utilization. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52(2):252–78. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper RS, Kennelly JF, Durazo-Arvizu R, Oh HJ, Kaplan G, Lynch J. Relationship between premature mortality and socioeconomic factors in black and white populations of US metropolitan areas. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):464–73. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch JW, Davey Smith G, Kaplan GA, House JS. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ. 2000;320:1200–204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ. 2001;322:1233–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sridhar D. Inequality in the United States Health. 2005. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2005/papers/HDR2005_Sridhar_Devi_36.pdf (Accessed 14th February 2011)

- 11.Marmot M. Inequalities in health. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):134–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackenbach JP, Bos V, Andersen O, Cardano M, Costa G, Harding S, et al. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in six Western European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:830–37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anonymous. Critical to success: the place of efficient and effective critical care service within the acute hospital. London: Audit Commission; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halpern NA, Pastores SM, Thaler HT, Greenstein RJ. Changes in critical care beds and occupancy in the United States 1985–2000: Differences attributable to hospital size. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2105–12. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227174.30337.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr BG, Addyson DK, Kahn JM. Variation in critical care beds per capita in the United States: implications for pandemic and disaster planning. JAMA. 2010;303(14):1371–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace D. Roots of increased health care inequality in New York. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(11):1219–27. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90127-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Türkkan A, Aytekin H, Wallace D. Socioeconomic and health inequality in two regions of Turkey. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):346–52. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldstein MS. Effects of Differences in Hospital Bed Scarcity on Type of Use. Br Med J. 1964;2(5408):561–64. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5408.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhagwanjee S, Scribante J. National audit of critical care resources in South Africa- unit and bed distribution. S Afr Med J. 2007;97(12 Pt 3):1311–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Grand J. Inequalities in health: the human capital approach. Welfare state programme pamphlet no. 1. London: London School of Economics; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan GH. Changes in regional inequality in rural China: decomposing the Gini index by income sources. Australian J Agr Econ. 2001;45(3):361–81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonetti M, Gigliarano C, Muliere P. The Gini concentration test for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 2009;15(4):493–518. doi: 10.1007/s10985-009-9125-5. Epub 2009 Sep 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin R. The Gini-index as a Measure of the Goodness of Prediction. Bull Econ Res. 1997;49(2):127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theodorakis PN, Mantzavinis GD. Inequalities in the Distribution of Rural Primary Care Physicians in Greece and Albania. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5(3):457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas V, Wang Y, Fan X. Measuring education inequality - Gini coefficients of education. World Bank; 2000. Available from: http://www.mendeley.com/research/measuring-educational-inequality-gini-coefficients-of-education/ (Accessed 14th Feb 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berndt DJ, Fisher JW, Rajendrababu RV, Studnicki J. Measuring Healthcare Inequities using the Gini Index. HICSS '03 Proceedings of the 36th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’03), 0-7695-1874-5/03.2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao CX, Zhuo L, Gu YM, Qin ZH. Study of large medical equipment allocation in Xuzhou. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007;8(12):881–4. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Collange O, Fowler R, Hoste EA, et al. Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2787–93. e1–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abu-Zaineh M, Mataria A. Assessing the Causes of Inequality in Health Care Delivery System in Palestine. The Palestinian Economy. 2010:341. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anonymous. Acute Health Division. 2011. Department of Human Services Victoria, Australia. Available from: http://www.dhs.vic.gov.au/ahs/archive/icu/contents.htm (Accessed 14th Feb 2011)

- 31.Amini N, Yadollahi H, Inanlou S. Ranking Of Country Provinces Health. Social Welfare. 2006;5(20):27–48. [in Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood J. Rural Health and Healthcare: a North West perspective. 2011 Available from: www.nwpho.org.uk/reports/ruralhealth.pdf (Accessed 14th February 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caiazzo A, Cardano M, Cois E, Costa G, Marinacci C, Spadea T, et al. Inequalities in health in Italy. Epidemiol Prev. 2004;28(3 Suppl):i–ix. 1–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Probst JC, Laditka SB, Wang JY, Johnson AO. Effects of residence and race on burden of travel for care: cross sectional analysis of the 2001 US National Household Travel Survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;9(7):40. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elder AT. Hospital Bed Accommodation Requirements of a Region. Ulster Med J. 1958;27(1):64–70. 71–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]