Abstract

Faun tail nevus is a posterior midline cutaneous lesion of importance to dermatologists as it could be a cutaneous marker for its underlying spine and spinal cord anomaly. We report a 13-year-old girl with excessive hair growth over the lumbosacral region since birth. There was associated spinal anomaly with no neurological manifestation affecting the lower spinal cord. The diagnosis was made on clinical basis. The patient reported for cosmetic disability. This case is reported for its clinical importance.

Keywords: Faun tail nevus, spinal dysraphism, silky down

INTRODUCTION

Faun tail nevus is a posterior midline cutaneous marker for underlying spinal abnormalities like spinal dysraphism. Failure of the caudal neuropore to close at the end of fourth week of intrauterine life results in neural tube defects like spinal dysraphism which may also involve tissues overlying the spinal cord.[1] Abnormal lumbar hypertrichosis may present as “Silky down” or a “Faun tail”. When this occurs away from the spine, it is known as simple nevoid hypertrichosis. Silky down presents as soft non - terminal hair, while a faun tail is a wide patch of coarse terminal hair, several inches long.[2]

CASE REPORT

A 13-year-old girl presented with excessive hair growth over the lumbosacral (LS) region since birth [Figure 1]. Her parents had noticed the hairy patch with coarse hairs over LS region at birth. There was no history of back pain, urinary incontinence, paresthesia or weakness of muscles of lower limbs. No previous medical opinion had been sought for her. The family history was nil contributory. She was born of a non-consanguineous marriage and has two elder siblings. She was born by vaginal delivery at term with normal developmental milestones. Local examination revealed a 15 × 25 cm circumscribed area of hypertrichosis with coarse dark terminal hairs of varying length overlying the LS region. Skin over the area was normal. Neurological examination did not reveal any abnormality. She had a normal gait with normal tendon jerks. Muscles revealed grade 5 power. She could perceive all modalities of sensations over the lower limbs. We diagnosed it as faun tail nevus.

Figure 1.

A tuft of terminal hairs in the LS region (Faun tail)

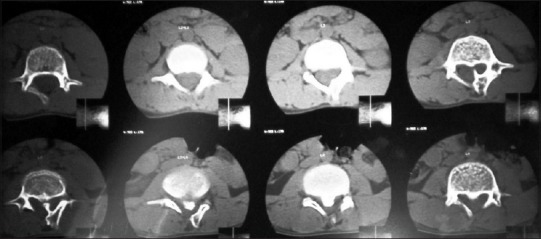

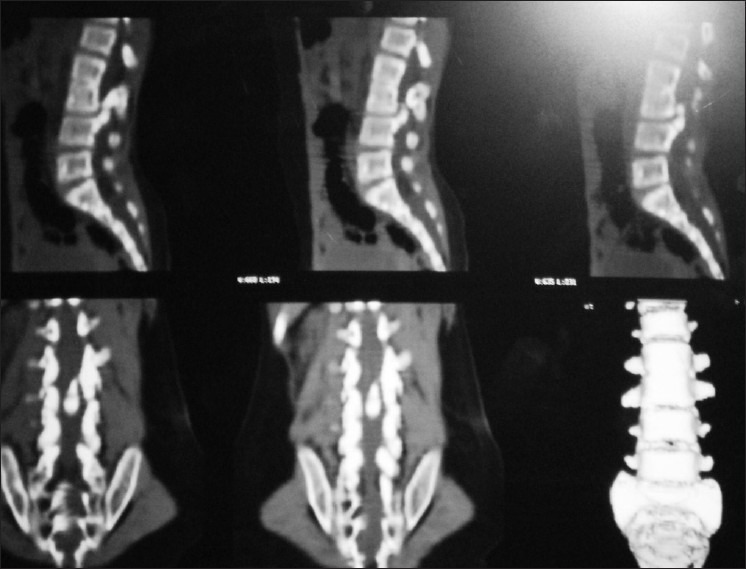

As this entity is a cutaneous marker of underlying spinal anomalies, an orthopedic opinion was taken and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the LS region was done. Serial axial sections of lumbar spine with saggital, coronal and 3D construction showed spina bifida of L2, L3, L4 and L5 vertebrae, with partially absent spinous process of the sacrum [Figures 2 and 3]. A complete bony septum was noted from the posterior surface of L4 body, extending upward and posterior to the left lamina of the L2 and L3 vertebrae. The left laminae of L2 and L3 vertebrae appeared widened and fused together. This bony septum divided the bony spinal canal into two compartments. The spinal canal and the thecal sac appeared divided along the midline into two parts at L3 and L4 levels. Distortion of the bony spinal canal contour was noted. L2 L3 disk space appeared reduced. No significant soft tissue defect was noted in the muscular planes. No obvious meningocele or myelomeningocele was noted.

Figure 2.

CT pictures of lumbar spine. Absent spinous process of L2 and left lamina (white arrow), narrowing of the spinal canal below with bony septum dividing the canal (diastometamyelia) (black arrows)

Figure 3.

CT pictures of LS region in lateral and AP view showing spina bifida and diastometamyelia

Spina bifida of L2 to L5 vertebrae with partially absent spinous processes of the sacrum and fusion of left laminae of L2 and L3 vertebrae was noted. Diastometamyelia at L3 - L4 level with distortion of the spinal canal contour was also seen.

DISCUSSION

The word “faun” refers to an Italian deity in human form with horns, pointed ears with goat's legs and tail. In certain racial groups such as African American, Asian and Hispanic, hypertrichosis in the LS region may be a normal entity.[3]

Spinal dysraphism is a generic term describing pathologic conditions related to improper closure of the caudal neuropore. It encompasses all the conditions associated with spina bifida.[4] Other cutaneous markers, to name a few, are dimples, dermal sinuses, subcutaneous lipomas, port wine stain, acrochordons, hemangiomas, aplasia cutis, telengiectasia, capillary malformation, etc.[5] The separation of the neuroectoderm from the epithelial ectoderm occurs in the third to fifth week of intrauterine life and is initiated along the posterior midline. The cleavage can be incomplete at any phase, so that a defect may appear in the skin, vertebrae, spinal cord, and/or central nervous system. Congenital hypertrichosis over the LS area is a sign of the underlying spinal dysraphism.[6] In occult cases of dysraphism, except for cosmetic disfigurement, treatment is rarely required for tethered cord or spinal instability. A good cosmetic result with intense pulsed light treatment was achieved in the patients with faun tail. Local anesthesia may be required before treatment of faun tail with laser or laser- like systems due to associated neurological abnormalities.[7]

Our patient had localized hypertrichosis with confirmed spina bifida and diastometamyelia but no neurological deficit. The patient was advised to undergo excision of bone spur and detethering of the cord by the neurosurgeon, as this could lead to neurological impairment in the future. She mainly reported for cosmetic disability and removal of hairs in the LS region. This case is reported for its rarity and absence of neurological deficit associated with the spinal anomalies and also to highlight that a thorough radiological and neurological examination is mandatory for such cases. The patient was advised cosmetic removal of hairs.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton DJ, Moss C. Neavi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol. 15. Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 104–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavafoghi V, Ghandchi A, Hambrick GW, Udverhelyi GB. Cutaneous signs of spinal dysraphism. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:573–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.114.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drolet BA. Cutaneous signs of neural tube dysraphism. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2000;47:813–23. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasnik AP, Shinagare A, Lalchandani UR, Gujrathi R, Pai BU. Rudimentary third lower limb in association with spinal dysraphism: Two cases. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41:72–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.30530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drolet B. Birthmarks to worry about: Cutaneous markers of dysraphism. Dermatol Clin. 1988;16:447–53. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atherton DJ, Moss C. Neavi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol. 5. Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2001. pp. 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdemir M, Balevi A, Engin B, Tol H. Treatment of Faun Tail Neavus with Intense Pulsed light. Photomed Laser Surg. 2010;28:435–8. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]