Abstract

Malignant syphilis or Lues maligna, commonly reported in the pre-antibiotic era, has now seen a resurgence with the advent of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Immunosuppression and sexual promiscuity set the stage for this deadly association of HIV and Treponema pallidum that can manifest atypically and can prove to cause diagnostic problems. We report one such case in a 30-year-old female who responded favorably to treatment with penicillin.

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, malignant syphilis, co-existence

INTRODUCTION

Malignant syphilis is a rare form of destructive syphilide, with rupia-like ulcerative lesions and severe toxemia, which may end in death.[1] Ulcers, commonly seen over the face and extremities,[2] are covered with thick crusts, which heal slowly. Mucus membranes of the mouth and nose may be involved and prodromes of fever, myalgia and headache are common.[3] These lesions were commonly reported in the pre-antibiotic era, and have now re-emerged with the advent of HIV.

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old housewife presented with multiple, large, ulcerative lesions all over the body of 1-month duration. She did not give any history of genital lesions before the onset of skin lesions. Concomitant symptoms of headache, fever, myalgia and leucorrhea were present. She also gave a history of two spontaneous miscarriages for which she had not taken treatment and has not had contact with her husband since 6 months. Her husband, a lorry driver had multiple extra and premarital contacts. He was diagnosed as having HIV 2 years ago and was initiated on antiretroviral therapy. He was currently being treated for chancroid as well, due to many genital ulcers that he presented to us with.

On examination, the patient was febrile. Cutaneous examination revealed multiple, ulcerative, crusted lesions on the face and extremities [Figures 1 and 2]. Erosions were present on the lips and genital mucosa as well. Palms [Figure 3] and soles showed multiple annular lesions with central pigmentation. The axillary, epitrochlear and inguinal lymph nodes were enlarged, tender and rubbery in consistency.

Figure 1.

Multiple crusted lesions with erosion of lips

Figure 2.

Crusted lesions of extremities

Figure 3.

Annular lesion with central pigmentation of the palms

Initial laboratory investigations revealed leucocytosis, with predominance of polymorphs and an elevated ESR. VDRL was reactive (1:128 dilution) and HIV-1 was positive (ELISA). Western blot assay for P24 antigen was also found to be positive. Pus culture from the ulcerated lesions grew Staphylococcus aureus which was highly sensitive to newer quinolones. CSF analysis showed no abnormalities of raised intracranial pressure, pleocytosis or elevated proteins. CSF VDRL was nonreactive in our patient.

VDRL of the patient's partner was found to be positive in 1:64 dilution. We initiated treatment with Benzathine penicillin G 24 lakh units intramuscularly as a single dose following which the partner was lost to follow-up.

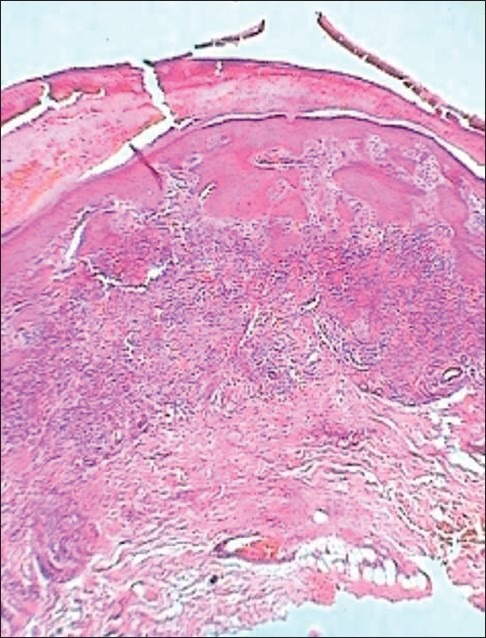

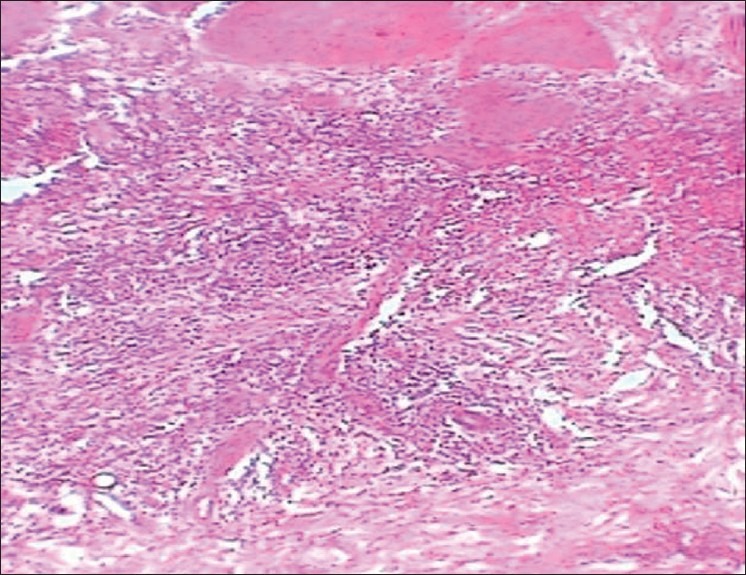

Skin biopsy of the rupioid lesions showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with ulceration, dense lymphocytic infiltrate at mid-dermal level on 20× magnification [Figure 4] and plasma cell infiltrate with obliterative vasculitis on 40× magnification [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Section on 20× magnification showing dense lymphocytic infiltrate

Figure 5.

Section on 40× magnification showing plasma cell infiltrate with endarteritis obliterans

Since the patient gave history of intense headache and fever we considered an impending CNS involvement and hence treatment was initiated with procaine penicillin 1.2 million units daily for 3 weeks intramuscularly, and we also took the advantage of admitting the patient in our hospital. She was also given a course of oral antibiotics to eliminate the S. aureus. Patient started responding to treatment and all her cutaneous lesions healed completely in 3 weeks [Figures 6 and 7]. Patient also showed leukoderma colli around her neck. She was discharged and referred to a HIV center for HAART therapy. Monthly VDRL titers were done, and there was a four-fold decrease in the titers. Follow-up after 6 months showed no evidence of relapse, with a nonreactive VDRL and positive TPHA.

Figure 6.

Resolved malignant syphilis of face

Figure 7.

Resolved malignant syphilis of extremities

DISCUSSION

It is not surprising that HIV and Treponema pallidum causing syphilis can co-infect the same person. Both organisms are sexually transmitted and the risk factors for their acquisition are also the same. In immunodeficient states, co-existing sexually transmitted diseases can present atypically.[4] Hence the diagnosis of malignant syphilis can occasionally prove to be challenging.

In Chandigarh, India, malignant syphilis was reported in two out of 55 patients with syphilis, from the year 1990-99; and among the study population one of three HIV-infected patient had malignant syphilis.[5] A review of publications in the English literature identified 14 cases of malignant syphilis reported between the early 1900s and 1988. From 1989 to 1994, an additional 12 cases were reported. Of those 12 cases, 11 occurred in patients who either were infected with HIV or were at high risk for HIV infection.[6]

It is still not clear why only some patients infected with T. pallidum have malignant syphilis. This could probably be attributed to the altered immune status of the host or to a virulent strain of T. pallidum. However, we do not have enough evidence regarding the virulence of the organism. This atypical form of syphilis with concomitant HIV can lead to accelerated neurosyphilis with which it commonly presents.[2] Surprisingly, CSF analysis in our patient showed a normal picture.

Similar cases[7,8] have been reported which stressed the atypical presentation of syphilis in a background of HIV infection and cautioned the clinician on maintaining a high index of suspicion to identify and treat this deadly association.

HIV-infected patients are at risk for developing malignant syphilis. Despite its malignant presentation penicillin still continues to play a promising role in treating this fatal disease.

Some of the features suggestive of syphilis and HIV co-infection are unusually high or low titers, a late fall in titer after successful treatment and a higher incidence of asymptomatic CNS involvement. Physicians also need to maintain a serological follow-up to document a four-fold fall in titer besides a stringent clinical documentation of resolution of symptoms.

This case is highlighted for the presence of malignant syphilis with HIV, an association which seems to be on a rise parallel with the rise of HIV infection.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schöfer H, Imhof M, Thoma-Greber E, Brockmeyer NH, Hartmann M, Gerken G, et al. Active syphilis in HIV infection: Multicenter retrospective survey.The German AIDS Study Group (GASG) Genitourin Med. 1996;72:176–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.72.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra CM. Syphilis and HIV infection. Semin Neurol. 1992;12:43–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1041156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher DA, Chang LW, Tuffanelli DL. Lues maligna.Presentation of a case and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:70–3. doi: 10.1001/archderm.99.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis and infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb04441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar B, Gupta S, Muralidhar S. Mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis in north Indian patients: A changing scenario? J Dermatol. 2001;28:137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sands M, Markus A. Lues maligna, or ulceronodular syphilis, in a man infected with human immunodeficiency virus: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:387–90. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad PV, Paari T, Chokkalingam K, Vijaybushanam V. Malignant syphilis in a HIV infected patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:192–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagarajan N, Adithyan S, Amalaraja D, Ganesh R. Lues maligna in a HIV positive woman. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2006;27:36–8. [Google Scholar]