Abstract

S-Adenosyl-l-methionine:l-methionine S-methyltransferase (MMT) catalyzes the synthesis of S-methyl-l-methionine (SMM) from l-methionine and S-adenosyl-l-methionine. SMM content increases during barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germination. Elucidating the role of this compound is important from both a fundamental and a technological standpoint, because SMM is the precursor of dimethylsulfide, a biogenic source of atmospheric S and an undesired component in beer. We present a simple purification scheme for the MMT from barley consisting of 10% to 25% polyethylene glycol fractionation, anion-exchange chromatography on diethylaminoethyl-Sepharose, and affinity chromatography on adenosine-agarose. A final activity yield of 23% and a 2765-fold purification factor were obtained. After digestion of the protein with protease, the amino acid sequence of a major peptide was determined and used to produce a synthetic peptide. A polyclonal antibody was raised against this synthetic peptide conjugated to activated keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The antibody recognized the 115-kD denatured MMT protein and native MMT. During barley germination, both the specific activity and the amount of MMT protein increased. MMT-specific activity was found to be higher in the root and shoot than in the endosperm. MMT could be localized by an immunohistochemical approach in the shoot, scutellum, and aleurone cells but not in the root or endosperm (including aleurone).

SMM is a very common nonprotein amino acid among flowering plants (Kovatscheva and Popova, 1977; Giovanelli et al., 1980; Maw, 1981; Gessler et al., 1991; Bezzubov and Gessler, 1992). In plants it can act as a methyl donor in the reaction with homocysteine to form Met (Turner and Shapiro, 1961; Allamong and Abrahamson, 1977; Giovanelli et al., 1980). However, other methyl-transfer reactions using SMM as the methyl donor are still speculative (Giovanelli et al., 1980).

SMM is believed to function as a storage form for methyl groups. When the capacity to form methyl groups de novo diminishes relative to the capacity to form homocysteine, the methyl groups stored could be returned to the Met pool (Giovanelli et al., 1980; Giovanelli, 1987; Mudd and Datko, 1990). This function is important for ethylene formation at the time of senescence in flower tissues (Hanson and Kende, 1976). However, the physiological role of SMM in plants is not yet fully understood.

In the salt-tolerant plant Wollastonia biflora (L.) DC, SMM is the first intermediate in the synthesis of DMSP, an important osmoprotectant compound (Hanson et al., 1994). In the same plant SMM is produced in the cytosol and then imported into the chloroplast, where it is converted to DMSP (Trossat et al., 1996). The accumulation of DMSP is important from an environmental point of view. DMSP is the major biogenic source of atmospheric DMS, an important compound in the global S cycle (Trossat et al., 1996, and refs. therein).

In plants that do not accumulate DMSP, such as barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), SMM presumably has a different metabolic role. It may be converted into Met or, by enzymatic hydrolysis, into DMS and homoserine (Gessler et al., 1991). The physiological importance of DMS is still speculative but it may contribute to the aroma of flowers (Gessler et al., 1991). During food processing SMM gives rise to homoserine and DMS by thermal degradation. DMS has an important role in flavoring many cooked vegetables (Tressl et al., 1977; Kovatscheva, 1978) and other foodstuffs, including tea (Ohtsuki et al., 1984) and beer, in which it can be considered undesirable (Anderson et al., 1975; Dufour, 1986).

SMM is synthesized from AdoMet and Met in a reaction catalyzed by MMT (EC 2.1.1.12). This enzyme has been purified to homogeneity from leaves of the DMSP-accumulating plant W. biflora (James et al., 1995). A better knowledge of MMT from a germinating seed such as barley is also of utmost importance from both a physiological and a technological standpoint. In this paper we report the purification and tissue-specific distribution of MMT from germinating barley.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Plant Material

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv Haruna Nijo) seeds were subjected to a 16-h-long imbibition in water, followed by 10 h of air rest, and 16 more h of imbibition, to reach a grain moisture of about 42%. Seeds were then allowed to germinate in a humidified clay pot. The entire procedure was done in the dark and the temperature was kept at 14°C. Samples were taken every 24 h and used either directly or after storage at −20°C.

Chemicals

AdoMet (p-toluene sulfonate salt) was purchased from Sigma. PEG 4000 was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The protein dye reagents and SDS-PAGE protein standards were from Bio-Rad. The conjugation kit (Inject) was from Pierce. Enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents were from Amersham. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium solution was from Boehringer Mannheim. All other chemicals were of the highest purity available.

Enzyme Assay and Protein Assay

MMT was assayed essentially as reported previously (Pimenta et al., 1995). The enzyme (50 μL) was incubated at 25°C in a medium (250 μL) containing 25 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.8), 0.80 mm [methyl-3H]AdoMet (7.6 kBq/assay), 1 mm Met, 1 mm DTT, and 100 μg mL−1 BSA. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 volumes of 10% (v/v) ethanol in water containing 10% (w/v) activated charcoal. The mixture was centrifuged at 17,000g for 5 min and 500 μL of the supernatant containing the newly synthesized, labeled SMM was added to 6 volumes of scintillation liquid and counted in a liquid-scintillation spectrometer.

One unit is the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of 1 μmol substrate min−1 under the standard conditions of the assay. Protein was estimated according to the method of Bradford (1976) using BSA as a standard. The specific activity was calculated as units per milligram of total protein.

Extraction and Purification of MMT

All steps of enzyme extraction and purification were performed at 0°C to 4°C. Germinated barley (5 d) was homogenized twice for 20 s with a Waring blender in 2 volumes of buffer A (25 mm sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.6] containing 50 mm KCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT). The homogenate was centrifuged at 4000g for 10 min. The supernatant containing the methyltransferase activity was used for the enzyme assays and purification, either directly or after storage at −80°C.

Crude enzyme extract (600 mL) was made 10% in PEG by the addition of 0.3 volume of a 44% (w/v) PEG solution in buffer A. The mixture was stirred for 15 min and allowed to stand for an additional 15 min. After the sample was centrifuged (15,000g, 40 min), the resulting supernatant was mixed with 0.8 volume of the 44% PEG solution in buffer A to reach a 25% concentration. The mixture was stirred for 15 min and allowed to stand for 15 min more. After the sample was centrifuged again (15,000g, 40 min), the pellet was suspended again in buffer B (20 mm Tris/acetic acid buffer [pH 7.8], 0.5 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT) containing 20 mm KCl and poured onto an XK DEAE-Sepharose column (1.6 × 20 cm, Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer B (20 mm KCl). The column was washed with 7.5 volumes of buffer B containing 20 mm KCl. Elution was then performed with 60 mL of buffer B (80 mm KCl), then by a linear gradient of 80 to 170 mm KCl in buffer B, and then with 30 mL of buffer B (170 mm KCl). Finally, the column was washed with 10 column volumes of buffer B containing 1 m KCl. The flow rate for sample application, washing, and elution was 2 mL min−1 and the fraction size was 3 mL. The active fractions (45–68) were pooled and poured onto a 4-mL adenosine-agarose column prepared as described by James et al. (1995) and equilibrated with buffer B (20 mm KCl). After the column was washed with 8 volumes of buffer B (200 mm KCl and 20% [v/v] glycerol), followed by a linear gradient of 200 to 600 mm KCl in buffer B containing 20% (v/v) glycerol, the enzyme was then eluted with 1 mm AdoMet in buffer B (25 mL) containing 600 mm KCl and 20% (v/v) glycerol. The flow rate for sample application, washing, and elution was 0.5 mL min−1, and the fraction size was 1 mL. Active fractions (103–123) were pooled and stored at −80°C after flash freezing in liquid N2.

SDS-PAGE

Active enzyme fractions of the different purification steps were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5% (w/v) gels (Laemmli, 1970) and visualized with silver staining (Oakley et al., 1980). Myosin (208 kD), β-galactosidase (115 kD), BSA (79 kD), and ovalbumin (49 kD) were used as the standard proteins. Prestained standard proteins were used for immunoblot applications.

Internal Peptide Sequence Analysis

Adenosine-agarose active fractions were concentrated to 100 μL with microconcentrators (30,000 nominal Mr limit, Millipore) and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The Coomassie blue-stained bands of 115 kD were excised (approximately 10 μg of protein) and digested with 0.5 μg of Achromobacter protease I (kindly supplied by Dr. Masaki, Ibaraki University, Inashiki, Japan) for 12 h at 37°C in 0.5 m Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) containing 0.2% (w/v) SDS. The resulting peptides were separated on columns of DEAE-5PW (2 × 20 mm, Tosoh Corp., Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) and Mightysil RP 18 (2 × 50 mm, Kanto, Tokyo, Japan) connected in series with a model 1000M (Hewlett-Packard) liquid chromatography system. Peptides were eluted, subjected to Edman degradation, and analyzed by an automated protein sequencer as described by Sekimoto et al. (1997).

Production of Polyclonal Antibodies and Immunoblotting Methods

Part of the major peptide fragment obtained from the peptide sequence analysis, (NH2)-ALDDDGLPIYDAEGKC-(COOH), was custom synthesized by Sawady Technology (Tokyo, Japan), Cys being added to the carboxyl terminus to allow coupling to the carrier protein. The synthetic peptide (2.5 mg) was conjugated to maleimide-activated keyhole limpet hemocyanin by using a conjugation kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. One milligram of the conjugated protein was injected into a rabbit four times at intervals of 2, 4, and 2 weeks. The antiserum collected 2 weeks after the last injection was used for immunoblots.

Proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE were transferred to an enhanced chemiluminescence, nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond N, Amersham) for 2 h at 120 mA in a mini-blot transfer cell (Nihon Eido, Tokyo, Japan). Blots were washed in TBS containing 0.2% (v/v) Tween 20. Blocking solutions were made in the same buffer containing 1% (w/v) nonfat milk powder. Blots were incubated with the antiserum diluted 1000-fold with the blocking buffer, and antigen-antibody complexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents using goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase as a secondary antibody.

Immunohistochemistry

The polyclonal antibody raised against the conjugated synthetic peptide was custom purified by immunoaffinity by Sawady Technology and used in the immunohistochemistry studies. The root, shoot (including scutellum), and endosperm (including aleurone and husk) from 5-d-germinating barley were separated and fixed at room temperature by infiltration under a vacuum for 10 min with a solution of 63% (v/v) ethanol containing 1.85% (w/v) formalin and 5% (v/v) acetic acid, and incubated for 2 h in the same solution. After dehydration, the samples were embedded with paraffin embedding medium (Paraplast Plus, Sigma). Longitudinal and cross sections (8 μm in thickness) were made from the embedded samples with a microtome. Paraffin was then removed from the samples using xylene, which was then washed out with ethanol. The samples were treated with an ethanol series and then washed in PBS and incubated in a PBS solution containing 50% (v/v) goat serum for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, with the purified antibody 300-fold diluted in a PBS solution containing 50% (v/v) goat serum and 0.2% (v/v) Tween 20. MMT was detected using a solution of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium and goat anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase as a secondary antibody and observed by light microscopy.

RESULTS

Purification of MMT

The crude enzyme extract prepared from 5-d-germinating barley was first subjected to a 10% to 25% PEG fractionation. This was an important cleaning step, since the pellet contained only 28% of the total protein present in the crude extract (Table I).

Table I.

Purification of MMT from germinating barley

| Step | Total Protein | Total Activity | Specific Activity | Activity Yield | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg | milliunits | milliunits mg−1 | % | -fold | |

| Crude extract | 3600 | 660 | 0.183 | 100 | 1 |

| PEG pellet (10%–25%) | 990 | 648 | 0.654 | 98 | 3.6 |

| DEAE-Sepharose | 70.2 | 428 | 6.10 | 65 | 33 |

| Adenosine-agarose | 0.302 | 153 | 506 | 23 | 2765 |

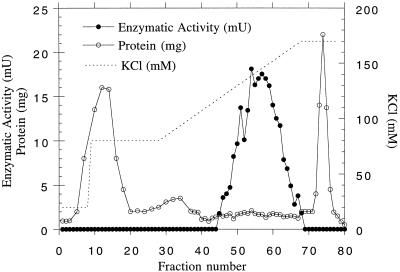

MMT in the 10% to 25% PEG pellet was then purified by DEAE-Sepharose chromatography. The enzyme was eluted by about 130 to 160 mm KCl in buffer B (Fig. 1). In this step, about 93% of the total protein present in the 10% to 25% PEG pellet could be separated from the active pool (Table I). This step was also important to remove some of the polysaccharides and pigments that were still present in the 10% to 25% PEG pellet.

Figure 1.

Elution profile of MMT from the DEAE-Sepharose column. A 10% to 25% PEG fraction of a germinating barley extract (550 mg of protein) was poured onto the column. Fractions of 3 mL were collected and each fraction was assayed for MMT activity and protein content. The dotted line represents the KCl gradient. mU, Milliunits.

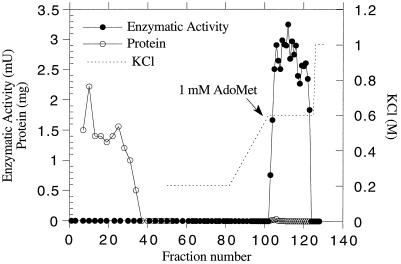

The pool of active fractions eluted from the DEAE-Sepharose column was directly applied to the adenosine-agarose column. The column was then washed with buffer B containing 20% glycerol, and the enzyme was eluted with buffer B (0.6 m KCl) containing 1 mm AdoMet and 20% glycerol (Fig. 2). The presence of 20% glycerol during the chromatography was necessary to stabilize the enzyme during this step and during storage. This chromatography allowed for an 83-fold purification with an activity yield of 36% (Table I).

Figure 2.

Elution profile of MMT from the adenosine-agarose column. The active fractions (45–68) collected from the DEAE-Sepharose column (Fig. 1) were pooled and 25 mg of protein was poured onto the column. Fractions of 1 mL were collected and each fraction was assayed for MMT activity and protein content. The dotted line represents the KCl gradient. AdoMet (1 mm) was added to the elution buffer (0.6 m KCl) as indicated by the arrow. mU, Milliunits.

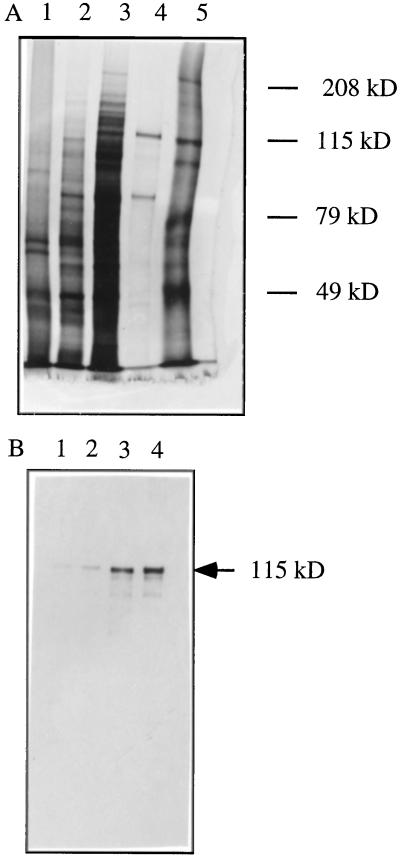

SDS-PAGE Analysis and Immunodetection

Protein fractions from the different purification steps were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). Two bands (80 and 115 kD) were still present in the most purified fraction (lane 4), but only the major 115-kD band correlated with the enzyme activity. Moreover, the 80-kD band could also be found in the nonactive fractions of the adenosine-agarose chromatography (not shown).

Figure 3.

SDS-PAGE (A) and immunoblot analysis (B) of samples taken through MMT purification. A, Fractions from the sequential purification steps were analyzed on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized by silver staining. Lane 1, Crude extract (1 μg); lane 2, 10% to 25% PEG pellet (1.5 μg); lane 3, DEAE-Sepharose pool (3.5 μg); lane 4, adenosine-agarose pool (0.3 μg); lane 5, molecular mass markers (kD). B, Fractions from the sequential purification steps were resolved on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by immunoblot using the polyclonal antibody raised against the conjugated MMT peptide. Lane 1, Crude extract (4.7 μg); lane 2, 10% to 25% PEG pellet (3.7 μg); lane 3, DEAE-Sepharose pool (1.5 μg); lane 4, adenosine-agarose pool (0.1 μg).

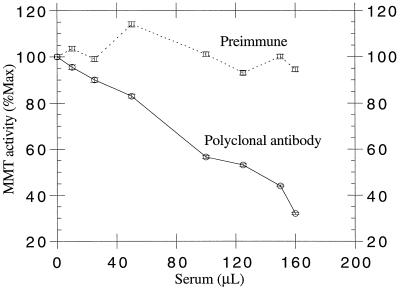

The 115-kD polypeptide band was cut from the Coomassie blue-stained polyacrylamide gel and subjected to cleavage with Achromobacter protease I specific for lysyl bonds. The resulting peptides were separated by reverse-phase chromatography, and from one of the major peptides, a 25-amino acid sequence (KIAWINLYLNALDDDGLPIYDAEGK) was obtained. The polyclonal antibody raised against the synthetic peptide (NH2)-ALDDDGLPIYDAEGKC-(COOH) combined to keyhole limpet hemocyanin selectively recognized the 115-kD polypeptide in each protein fraction of the different purification steps (Fig. 3B). This antibody could also neutralize the MMT activity when incubated with active fractions from the DEAE-Sepharose column (Fig. 4), showing that it could also react with the native MMT. MMT was not neutralized by incubation with the same amounts of preimmune serum.

Figure 4.

Immunotitration of MMT with a polyclonal antibody raised against the combined protein. A sample of the pool of DEAE-Sepharose active fractions (25 μL, 15 μg) was incubated with different amounts of antiserum raised against the combined protein or preimmune serum, and MMT activity was measured. Data are the means ± se of two to three experiments.

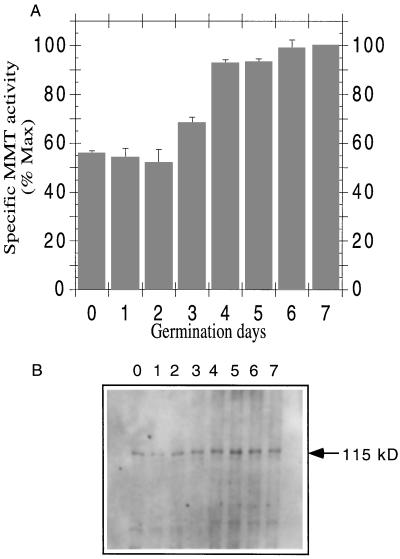

MMT during Barley Germination

Samples were taken from germinating barley between d 0 (dry barley kernels before germination) and d 7 (counting after starting the imbibition) and crude protein extracts were made. Total protein and MMT activity were determined for each extract and the specific activity was calculated. MMT specific activity did not change significantly during the first 2 d of germination, increased during the 3rd and 4th d, and leveled out after that (Fig. 5A). Immunoblot analysis showed a similar pattern for the protein content (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

MMT activity and protein level during barley germination. A, Crude extracts were prepared for each day of germination. D 0 corresponds to a crude extract obtained from barley kernels before germination. MMT activity was determined on 50 μL of the respective crude extracts. Data are the means ± se of three experiments, and values are plotted as percentages of maximum specific activity (specific activity of 7-d germination). B, Crude extracts (10 μg of protein) after various germination times (0–7 d) were resolved on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by immunoblotting.

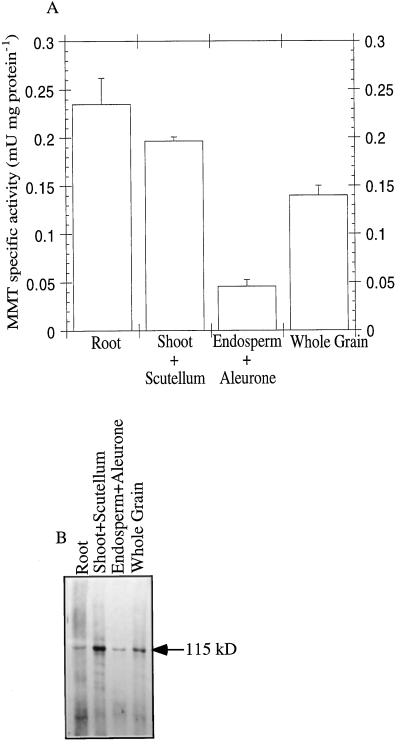

Distribution of MMT in 5-d-Germinating Barley

Crude protein extracts were made from root, shoot plus scutellum, and endosperm tissues (including aleurone) of 5-d-germinating barley. MMT activity and total protein content were measured. The MMT specific activity was the highest in root and shoot plus scutellum (Fig. 6A). Immunoblot analyses showed the same tendency as the specific enzymatic activity for shoot plus scutellum, endosperm (including aleurone), and whole grain but not for the root, in which the signal was low in comparison with the specific activity (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Distribution of MMT in 5-d-germinating barley. A, Crude extracts were prepared from 5-d-germinated barley root, shoot plus scutellum, endosperm (including aleurone), and whole grain using 2 volumes of extraction buffer (buffer A) as described in Methods. Data are the means ± se of three experiments. B, Crude protein extracts of the different grain parts (10 μg of protein) were loaded onto a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and subjected to immunoblot analysis. mU, Milliunits.

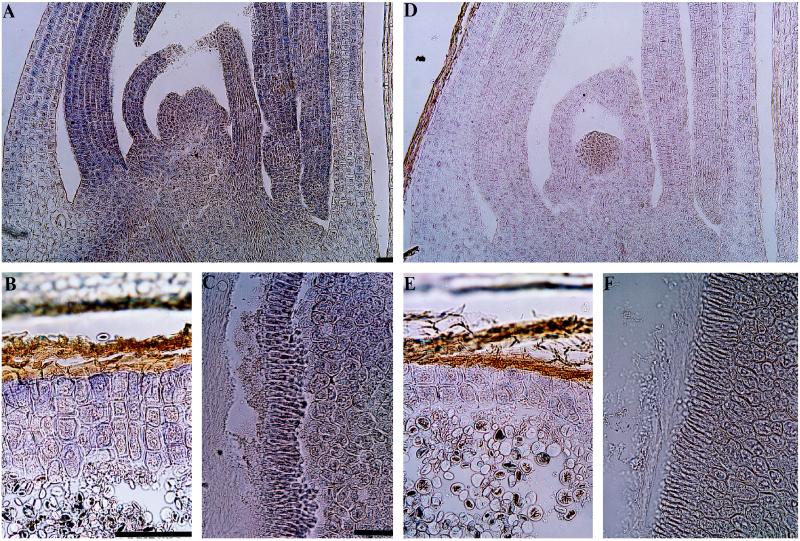

Immunohistochemistry

Immunoblot analysis showed that the immunoaffinity-purified antibody selectively recognized the 115-kD polypeptide in crude protein extracts from 5-d-germinating barley (not shown).

Longitudinal and cross-sections were made from different parts of 5-d-germinating grains and incubated with the immunoaffinity-purified antibody. Longitudinal sections of the shoot showed that MMT was abundant, particularly in the first three leaves, but was weakly detected in the coleoptile (Fig. 7A). Cross-sections of the endosperm showed that MMT was localized in aleurone cells (Fig. 7B) but was not detected inside the endosperm. Cross-sections of the scutellum also showed the presence of MMT in the scutellar epithelium (Fig. 7C). Sections shown in Figure 7, D to F, were incubated with preimmune serum as negative controls for Figure 7, A to C, respectively.

Figure 7.

Tissue localization of MMT in 5-d-germinating barley. Immunoaffinity-purified polyclonal antibody raised against the conjugated MMT peptide was used as a primary antibody, and goat anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase was used as a secondary antibody. The purple color indicates the presence of the MMT. A and D, Longitudinal sections of shoot showing that MMT is immunolocalized in almost all parts of the shoot (A), but in the first, second, and third leaves the signal is stronger. B and E, Cross-sections of endosperm, including aleurone. C and F, Cross-sections of the scutellum. MMT is localized in aleurone cells (B) and in the scutellar epithelium (C). Negative controls were made from the same source of embedded material, replacing the immunoaffinity-purified antibody by preimmune serum (D–F). The bars represent 100 μm. A and D, ×34; B and E, ×170, C and F, ×85.

DISCUSSION

A simple purification scheme for MMT from germinating barley has been established. It consists of a 10% to 25% PEG fractionation, an anion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sepharose, and an affinity chromatography on adenosine-agarose. The two first steps allowed us to discard a majority of undesired proteins, whereas the highly specific affinity step accomplished the final separation and furnished almost homogeneous active fractions. Considering the whole procedure, a good activity yield and a high purification factor were obtained (23%, 2765-fold). The specific activity of the most purified fraction was 3-fold higher than that of the homogeneous MMT purified from Wollastonia biflora leaves (506 and 146 nmol min−1 mg−1, respectively; James et al., 1995). In the affinity-chromatography step, the presence of 20% glycerol was necessary for the stability of the enzyme during the purification and storage. As reported earlier (Pimenta, 1996), the activity yield for this step was only about 10% in the absence of glycerol, and the enzyme activity was almost completely lost upon storage at −80°C after flash freezing in liquid N2.

SDS-PAGE of the most purified fractions still revealed the presence of the 115- and 80-kD bands. However, only the 115-kD fraction correlated with the enzymatic activity in the adenosine-agarose chromatography, indicating that the 80-kD fraction was a contaminant. The value of 115 kD is in agreement with the results obtained from a homogenous preparation of MMT from W. biflora leaves (James et al., 1995).

Immunoblot analysis showed that the polyclonal antibody raised against a conjugated MMT peptide selectively recognized the 115-kD polypeptide. This polyclonal antibody also recognized the native MMT, because it was able to reduce MMT activity in vitro when incubated with partially purified fractions, whereas the preimmune serum had no effect.

The highest content of SMM in plants corresponds to the germination stage, as reported by Gessler et al. (1991). Dethier et al. (1991) measured SMM content during barley germination and reported that SMM was not present in raw barley, remained negligible during the early stages of germination, and increased rapidly after the 4th d of germination. In the present work we followed MMT during barley germination, at both the activity and protein levels. Our data show that MMT was already present in an active form in the dry grain. Its activity measured in vitro and expressed per milligram of total protein (specific activity) did not change significantly during the first 2 d of germination but increased during the 3rd and 4th d. Immunoblot analysis also showed that the protein level during germination followed the pattern of the specific activity. Thus, the SMM content does not follow the MMT activity measured in vitro. SMM may be rapidly consumed during the early period of germination for the production of Met in a reaction catalyzed by S-methylMet:homocysteine S-methyltransferase (EC 2.1.10). In wheat this enzyme was active in the dry seeds and at the early stages of germination (Allamong and Abrahamson, 1977). The conversion of SMM into Met in periods of high metabolic activity, such as the early stages of germination, is in agreement with the hypothesis of its storage function. However, because the MMT was measured in vitro, a possible inhibition of the MMT activity or a lack of its substrates in early germination should be considered. Further investigation is necessary to clarify this point. A kinetic study of MMT should be performed, as well as the determination of the concentration of its substrates, products, and possible effectors.

Dethier et al. (1991) determined the SMM content in the different parts of the grain on a per-day basis and reported that the shoot (including scutellum), followed by the root, were the major contributors to the SMM content of germinating barley grain. But shoot content is higher than in root. They also suggested that the SMM content of the endosperm fraction (with aleurone) was attributable to SMM diffusion from the shoot (including scutellum). To study the distribution of the MMT, we analyzed the MMT enzyme activity and total protein content in the different parts of the grain of 5-d-germinated barley. The most important levels of MMT-specific activity were concentrated in the root and shoot plus scutellum. Low specific activity was found in the endosperm part (containing aleurone), and for the whole grain we obtained an intermediate value for the MMT-specific activity, as expected. The immunoblot approach showed that the MMT content was especially high in the shoot and low in the endosperm (containing aleurone). The immunoblot data were well correlated with the specific activity of the shoot, endosperm, and whole grain. For the root, however, a very weak signal was detected by immunoblot analysis, even though the specific activity found in the root extract was high, comparable to that of the shoot plus scutellum. The weak signal in root extracts suggests the presence of an MMT isoenzyme with a low cross-reaction with the antibody. Previously, we did not have any other indication of the presence of an MMT isoenzyme. Supporting the existence of a root isoenzyme, the MMT activity in root extracts was not reduced after incubation with the polyclonal antibody (data not shown).

An immunohistochemistry approach was used to localize MMT in the different parts of the grain. In the root a clear signal could not be detected. This result supports the hypothesis of the presence of a specific isoenzyme in this tissue. MMT was widely distributed in the shoot; however, the first, second, and third leaves presented the strongest signal. In the coleoptile a weak signal has been detected. MMT was detected in the scutellar epithelium and in aleurone cells but could not be detected in the endosperm. Gessler et al. (1991) found no correlation between SMM content and MMT activity in different parts of several plants, suggesting that SMM could be transported or actively utilized. Our results indicate that MMT may be involved in converting Met derived from the degradation of storage protein in the endosperm into SMM in aleurone and the scutellar epithelium. SMM can then be transported to other parts of the developing seedling, where it can be converted back into Met. These results suggest that in germinating barley SMM may function in both a storage and a transport form for labile methyl moieties. However, further experiments are necessary to clarify this point.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Andrew Hanson (University of Florida) for discussions and valuable comments concerning this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Koji Takio (RIKEN) for helpful guidance regarding peptide sequence analysis.

Abbreviations:

- AdoMet

S-adenosyl-l-Met

- DMS

dimethylsulfide

- DMSP

3-dimethylsulfoniopropionate

- MMT

S-adenosyl-l-Met:l-Met S-methyltransferase

- SMM

S-methyl-l-Met

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Frontier Research Program of the Japanese government. M.J.P. received a Japanese Science and Technology fellowship.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allamong BD, Abrahamson L. Methyltransferase activity in dry and germinating wheat seedlings. Bot Gaz. 1977;138:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Clapperton JF, Crabb D, Hudson JR. Dimethyl sulphide as a feature of lager flavor. J Inst Brew. 1975;81:208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Bezzubov AA, Gessler NN. Plant sources of S-methylmethionine. Prikl Biokhim Microbiol. 1992;28:423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethier M, Jaeger BD, Barszczak E, Dufour JP. In vivo and in vitro investigations of the synthesis of methylmethionine during barley germination. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 1991;49:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour JP. Direct assay of S-methylmethionine using high-performance liquid chromatography and fluorescence techniques. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 1986;44:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gessler NN, Bezzubov AA, Podlepa EM, Bykhovskii VY. S-methylmethionine (vitamin U) metabolism in plants. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 1991;27:192–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli J. Sulfur amino acids in plants: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli J, Mudd SH, Datko A (1980) Sulfur amino acids in plants. In BJ Miflin, ed, The Biochemistry of Plants, Vol 5. Academic Press, New York, pp 453–505

- Hanson AD, Kende H. Methionine metabolism and ethylene biosynthesis in senescent flower tissue of morning glory. Plant Physiol. 1976;57:528–537. doi: 10.1104/pp.57.4.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson AD, Rivoal J, Paquet L, Gage DA. Biosynthesis of 3-dimethylsulfoniopropionate in Wollastonia biflora (L.) DC. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:103–110. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James F, Nolte KD, Hanson A. Purification and properties of S-adenosyl-l-methionine:l-methionine S-methyltransferase from Wollastonia biflora. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22344–22350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovatscheva EG. Stability of S-methylmethionine in buffer solutions and vegetable juices in the course of thermal treatment. Nahrung. 1978;22:315–321. [Google Scholar]

- Kovatscheva EG, Popova JG. Natural sources of S-methylmethionine and stability of some of them during storage. Nahrung. 1977;21:465–472. doi: 10.1002/food.19770210602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maw GA. The biochemistry of sulphonium salts. In: Stirling CJM, Patai S, editors. The Chemistry of the Sulphonium Group, Part 2. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1981. pp. 703–770. [Google Scholar]

- Mudd SH, Datko AH. The S-methylmethionine cycle in Lemma paucicostata. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:623–630. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley BR, Kirsch DR, Morris NR. A simplified ultrasensitive stain for detecting proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1980;105:361–363. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki K, Kawabata M, Taguchi K, Kokura H, Kawamura S. Determination of S-methylmethionine in various teas. Agric Biol Chem. 1984;48:2471–2475. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenta MJ (1996) Study of S-adenosyl-l-methionine:l-methionine S-methyltransferase from green barley malt. PhD thesis. Catholic University of Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

- Pimenta MJ, Vandercammen A, Dufour JP, Larondelle Y. Determination of S-adenosyl-l-methionine:l-methionine S-methyltransferase activity by selective adsorption of [methyl-3H]S-adenosylmethionine onto activated charcoal. Anal Biochem. 1995;225:167–169. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimoto H, Seo M, Dohmae N, Takio K, Kamiya Y, Koshiba T. Cloning and molecular characterization of plant aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15280–15285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tressl RDB, Holzer M, Kossa T. Formation of flavor components in asparagus. 2. Formation of flavor components in cooked asparagus. J Agric Food Chem. 1977;25:459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Trossat C, Nolte KD, Hanson AD. Evidence that the pathway of dimethylsulfoniopropionate biosynthesis begins in the cytosol and ends in the chloroplast. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:965–973. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JE, Shapiro SK. S-methylmethionine and Sadenosylmethionine-homocysteine transmethylase in higher plant seeds. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961;51:581–584. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]