Abstract

Purpose

To prospectively compare outcomes and processes of hospital-based early palliative care with standard care in surgical oncology patients (N = 152).

Methods

A randomized, mixed methods, longitudinal study evaluated the effectiveness of a hospital-based Pain and Palliative Care Service (PPCS). Interviews were conducted presurgically and at follow-up visits up to 1 year. Primary outcome measures included the Gracely Pain Intensity and Unpleasantness Scales and the Symptom Distress Scale. Qualitative interviews assessed social support, satisfaction with care, and communication with providers. Survival analysis methods explored factors related to treatment crossover and study discontinuation. Models for repeated measures within subjects over time explored treatment and covariate effects on patient-reported pain and symptom distress.

Results

None of the estimated differences achieved statistical significance; however, for those who remained on study for 12 months, the PPCS group performed better than their standard of care counterparts. Patients identified consistent communication, emotional support, and pain and symptom management as positive contributions delivered by the PPCS.

Conclusions

It is unclear whether lower pain perceptions despite greater symptom distress were clinically meaningful; however, when coupled with the patients’ perceptions of their increased resources and alternatives for pain control, one begins to see the value of an integrated PPCS.

Keywords: Cancer malignancies, Palliative care, Pain management, Symptom management, Mixed methods

Introduction

Patients with advanced malignancies generally experience multiple symptoms related to cancer and cancer treatment. These symptoms may include, but are not limited to, (1) physical symptoms such as pain, nausea, dyspnea, and fatigue; (2) cognitive changes such as delirium, memory problems, and impaired concentration; (3) effective experiences such as anxiety and depression; and (4) spiritual distress such as grief and abandonment. Symptom severity is related to both the extent of the disease and the aggressiveness of the therapies including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and biological therapies. There is an increasing expectation that the control of pain and other symptoms and the relief of suffering throughout the spectrum of the disease should be included in what health care has to offer [5].

A clearly held tenant of palliative care is that it is an individual-centered approach concerned with more than the side effects of treatment or progressive disease burden. It focuses on both the quality of life remaining to patients and supporting their families and those close to them [16]. Patients with advanced malignancies require individualized complements of palliative care, where the emphasis extends beyond pain and basic symptom management to include the resolution of emotional, social, psychological, and spiritual problems, the provision of information, improved communication, and support for the family [18, 38]. In order to understand an individual’s palliative care experience, studies must go beyond standardized measures of quality of life that impose narrowly defined conceptual models with domains that have been preselected and restrict a patient’s choice of what constitutes their individual quality of life perceptions [4].

Thorough and holistic assessments of patients’ end-of-life needs are essential for providing optimal and compassionate palliative care; yet, the complexity of these needs for both patients and clinicians is poorly understood during end-of-life transitions [1]. Communication between interdisciplinary providers as well as between the providers and their patients and families is paramount in delivering optimal palliative care; yet, studies evaluating palliative care interventions often omit the quantity and quality of this communication. Mixed methods approaches that focus on unraveling the meaning of patients’ varying experiences and perceptions hold promise in providing clinicians with guidance in how to approach the individualization of palliative care interventions [1, 41].

Pain and palliative care outcomes

The quality of studies evaluating hospital-based palliative care teams has varied over time. A previous review of the literature regarding the efficacy of hospital palliative care teams revealed a lack of well-designed clinical research [18]. The nature of the palliative care interventions described in this review varied widely ranging from individual nurses with unspecified training to multi-professional teams. Outcomes of interest generally include pain, quality of life, patient satisfaction, symptom management, and service-related outcomes. However, comparisons across studies continue to be problematic because of the lack of consensus on palliative care outcome measurement tools [32].

Despite small sample sizes and relatively high attrition rates, most studies have indicated a small positive effect of hospital-based teams [18]. Mazzocato et al. also identified many of the same outcome variables including pain, symptoms, depression, coping, family structure, and communication with health care professionals [27]. In a more recent randomized controlled trial (N = 322), patients with advanced cancer who received nurse led palliative care had higher quality of life and mood scores but did not experience improvements in symptom intensity or reduced hospital days [2]. Similarly, Ternel and colleagues [40] found that among patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (N = 151), early palliative care resulted in significant improvements in both quality of life and mood. Neither of these two most recent studies explored the qualitative nature of the individuals’ experiences beyond patient-reported measures.

This paper presents a longitudinal, multiphase, concurrent mixed methods study exploring the process and outcomes of an interdisciplinary palliative care consult team in a research intensive environment. The following three research questions were examined:

Did a hospital-based pain and palliative care team intervention improve the process and outcomes related to pain and symptoms management in patients with advanced malignancies who were undergoing major surgical procedures in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surgery Branch protocols.

Was there a difference in the patient’s perceived support regarding pain and symptom management for those patients who received early individualized, interdisciplinary symptom, and pain management from the PPCS versus patients who received standard protocol pain and symptom management?

Did patients (and family) who received early individualized, interdisciplinary symptom, and pain management from the Pain and Palliative Care Service (PPCS) differ in their level of satisfaction with care over time from patients (and family) who receive standard protocol pain and symptom management?

Methods

Study design

This was a randomized controlled multiphased, longitudinal, mixed methods trial of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Clinical Center (CC), PPCS intervention compared to usual care for patients with advanced malignancies who were undergoing surgical procedures in NCI Surgery Branch clinical trials. The baseline sample for this study included 152 participants, 76 in the early palliative care arm and 76 in the standard care arm (Table 1). Participants were randomized to receive either early palliative care beginning postoperatively or standard care. For the purposes of this study, standard pain and symptom management provided to the control group were considered to be good clinical practice, which at times included individual consultations such as nutrition, social work, spiritual ministry, recreation therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and/or clinical psychiatry. If standard pain and symptom management were insufficient to meet the needs of a patient assigned to the usual care group, study participants were permitted to crossover to the treatment arm of the study at the clinical discretion of the attending physician.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of study participants (N = 152)

| Variable | SoC (n = 76) | PPC (n = 76) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) | ||

| Male | 37 (48.7) | 44 (57.9) |

| Female | 39 (51.3) | 32 (42.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity (n, %) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 66 (86.8) | 63 (82.9) |

| Latino/Latina | 2 (2.6) | 3 (3.9) |

| Black/African American | 5 (6.6) | 5 (6.6) |

| Other | 3 (3.9) | 5 (6.6) |

| Education (n, %) | ||

| < High school graduate | 4 (5.3) | 0 |

| High school graduate | 19 (25) | 23 (30.3) |

| Some college | 18 (23.7) | 8 (10.5) |

| College graduate | 18 (23.7) | 22 (28.9) |

| Postgraduate education | 17 (22.4) | 23 (30.3) |

| Marital status (n, %) | ||

| Married | 55 (72.4) | 62 (81.6) |

| Never married/single | 9 (11.8) | 2 (2.6) |

| Divorced | 4 (5.3) | 8 (10.5) |

| Widowed | 7 (9.2) | 3 (3.9) |

| Missing | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

No statistically significant group mean differences

The primary outcomes were patient-reported pain and symptom intensity. Secondary patient-reported outcome measures included mood, social support, and satisfaction with pain and symptom management. In addition to exploring quantitative outcome measures, our study used a concurrent mixed methods approach including open-ended qualitative questions in order to provide insight into patient and family member perceptions regarding palliative care delivery and communication with health care providers. The mixed methods approach used was concurrent in that quantitative and qualitative data were collected during a single-phase study with side-by-side comparison and integration of both sets of data as appropriate [6–8]. Our intent with this concurrent design was to more thoroughly understand each patient’s experience through objective and subjective measures.

Patient registration and treatment randomization

The study was approved by the NCI Institutional Review Board (IRB). Once written consent was obtained, patients were randomized to the standard care (control) or early palliative care (treatment) group. Patients assigned to the treatment group received a medical order for a consult with the PPCS. Face-to-face interviews were conducted prior to surgery, within the first 24 h postoperatively, and during follow-up staging visits at 4–6 weeks, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. All interviews were conducted in an outpatient clinic setting with the exception of the preoperative interview that was conducted on the surgical oncology patient care unit and the 24 h postoperative interview that was conducted in the intensive care unit (ICU). Pain and symptom outcomes, the primary outcomes, were assessed at all time intervals. Secondary outcomes were assessed less frequently with mood assessed at baseline, 6 and 12 months. Social support and open-ended qualitative questions regarding satisfaction with pain and symptom management were included at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months.

Hospital-based pain and palliative care team

The PPCS is a consult team available to all patients who are actively participating in research studies throughout the NIH, CC. There are over 6,000 patient visits per year made by this team. The patients are seen as inpatients as well as in an outpatient clinic setting. The team was established in August of 2000 and at the time of the study had two full time attending physicians, three nurse practitioners, a nurse thanatologist (member of the team who specialized in the psychosocial and emotional aspects of death and dying), and one physician fellow in Hospice and Palliative medicine. The extended team included spiritual ministry, social work, recreation therapy, counseling, nutrition, acupuncture, acupressure, massage, reiki, rehabilitation medicine. Each consult included a full assessment of pain and other symptoms, what treatments had been implemented, and what were the most bothersome and disruptive to the patient. The consult covered not only physical symptoms, but emotional and spiritual distress. The patient was usually offered varied modalities of treatment, pharmacologic as well as complementary therapies. The philosophy of the team was to provide comfort care for symptom burden earlier in the disease process to improve quality of life.

Outcome and process measures

Process and outcomes of the PPCS were evaluated through face-to-face patient and family interviews using a series measures including (1) APACHE II (severity of illness); (2) Gracely Pain Scale (pain intensity and unpleasantness); (3) Symptom Distress Scale (symptom burden); and (4) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (mood/depression). Social support, satisfaction with care, and perceptions of communication with health care providers were evaluated using concurrent open-ended, qualitative questions.

The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score provided a measure of severity of illness using physiologic parameters collected after admission to the intensive care unit and was included to verify that there were no significant differences in postoperative acuity between the treatment and control groups [9, 23, 30].

Pain intensity and unpleasantness were measured using the Gracely Pain Scales (GPS). The GPS is designed to measure the intensity and unpleasantness of the individual’s pain sensation with the aid of verbal pain descriptors. The 13 multiple verbal descriptors cover the entire pain range, minimizing floor, and ceiling effects [12]. Scoring involves locating each of the 13 verbal descriptors along a visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 20. The location along the VAS for a descriptor is used as the numerical score for that descriptor. The patient’s score is determined by the descriptor that they choose as best representing their perceived pain intensity or unpleasantness severity. The VAS creates a ratio scale for the descriptors, as the minimum VAS score is 0. The psychometric properties of the scales, assessed using ratio scaling techniques, have indicated that the scores assigned to the descriptors demonstrate good internal consistency, reliability, and objectivity [11, 13, 26, 28].

The Symptoms Distress Scale (SDS) is a validated, 13-item self-report Likert scale measure used to measure the degree of distress associated with 11 symptoms: nausea, appetite change, insomnia, pain, fatigue, bowel changes, concentration, appearance, worry, breathing, and cough [21, 29, 33, 35, 36, 39]. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of symptom distress. A score of one represents normal or no distress for a given symptom, while a score of five represents experiencing the symptom almost constantly.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item well-validated measure to assess current frequency of depressive symptoms, with an emphasis on depressed affect or mood, and was originally intended for use with cross-sectional samples in survey research [34, 37].

Improving overall patient and family satisfaction is an essential outcome of pain and palliative care. Communication, information giving, and practical support, between patients, their families, and health care providers all have a major effect on pain and symptom relief as well as on their overall quality of life [17]. Qualitative, open-ended questions were designed to provide insight into individual patient and family experiences regarding issues in care delivery, communication, social support, and overall patient satisfaction. Open-ended questions included the following:

From your past experiences with others who have assisted you with pain and symptom management, can you describe what makes your treatment here the same? What makes it different?

Are you satisfied with your current pain and symptom management? Describe.

A broad definition of social support refers to the functional content of relationships [20]. Our study focused on the individual’s self-report of perceived and enacted social support as it related to their illness and pain/symptom management Perceived social support is operationalized as the “cognitive appraisal of being reliably connected to others.” Perceived social support differs from being socially embedded in that measures of perceived social support do not quantify either the number of social supporters or the amount of social contact [3, 43].

There are a number of validated instruments for the measurement of social support in other patient populations [15, 19]. However, due to the length of these instruments, the response burden to participants in this study was deemed to be too great. To minimize respondent burden and to provide patients with the opportunity to identify their sources of support and their level of satisfaction in their own words, the variables of social support and satisfaction with care were added as part of a semi-structures qualitative questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative analysis

Analysis Groups: Patients assigned to pain and palliative care began their treatment experience immediately after randomization. Patients in the usual care group who crossed over did not have this support from the onset of the study or postoperative period, a very critical and influential time in the treatment and disease trajectory. Thus, we considered two groups of patients: those receiving pain and palliative care from the beginning of the study and those who did not. This is essentially an intent-to-treat analysis. Summary statistics were used to describe the two groups at the preoperative and 24-h postoperative time points. Number of patients, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum were used to summarize distributions of the continuous measures; counts and percentages were used for categorical measures. Calculations were performed using SAS v9.2.

Cox proportional hazards models with time-varying covariates were used to explore factors related to time on usual care treatment until crossover, and time on study until discontinuation. These models incorporate changes in the predictor variables that accompany change in the outcome variable. For crossover among the usual care patients, predictors used were postoperative APACHE II, CES-D at baseline, and time-varying pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and SDS scores. For study discontinuation, the same set of scores plus treatment group and time-varying crossover status were included. The SAS PHREG (proportional hazards regression) procedure was used to fit the model.

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to explore treatment effects over time on pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and symptom distress. These models included a random effect for patient (measurements within the same patient are a dependent cluster), and fixed effects for assigned treatment, linear and quadratic time (assessment 1 through 7), postoperative APACHE II symptom severity score, and time-varying CES-D score (carried forward from baseline until the 6-month assessment and then from 6 months until the 12-month assessment). Interaction terms for time by treatment for CES-D score and APACHE II were included. A dropout pattern mixture was added to the model to mitigate potential bias in the estimates obtained from the mixed model attributable to self-selected study discontinuation. For the dropout pattern, three groups of discontinuers were identified, they are as follows: those dropping out for any reason prior to the 3-month assessment, those dropping out after the 3-month assessment but before the 12-month assessment, and those who completed the entire 12 months on study. The completers were considered the reference group for modeling purposes. A fixed effect and interaction terms for dropout group by all other aforementioned terms in the model (assigned treatment, linear and quadratic time, postoperative APACHE II score, time-varying CES-D score, plus interaction terms for time by treatment, time by CES-D score, and time by APACHE II) were included in the model. This allowed the unique effects for each dropout group to be estimated. For example, the main effect of the APACHE II score on the outcome variable is the effect for the reference group, the completers. The interaction of the categorical dropout group variable with the APACHE II term would produce estimates of (1) the differential effect of APACHE II for those dropping out before 3 months compared with completers, and (2) the differential effect of dropping out at 3–9 months compared with completers. The SAS MIXED procedure was used to fit the model.

Qualitative analysis

Transcript-based analysis of the data is considered to be the most rigorous choice for analyzing the information generated during the focus groups [24]. The general analysis plan included identify the major themes, considering the choice and meaning of the words used to describe each individual’s experience, and considering the context and consistency of individual responses. To maximize validity, all transcripts were analyzed by an independent blinded reviewer (CM-D) followed by independent reviews by the principal investigator (GW) as well as a member of the palliative care team (KB). The thematic areas were then verified through a joint meeting, and consensus was met between all three reviewers. Qualitative computer analysis using NVivo 7 provided an additional tool to index and cross-reference participant responses. Using the computer program to locate coded sections of the transcript is called searching and is considered the most powerful advantage of applying a software package [31].

Results

The baseline sample for this study included 152 participants (76 in the early palliative care arm and 76 in the standard care arm). By the 3-month assessment, 107 participants (70.4%) remained on study (54 pain and palliative care; 53 standard of care), and by 12 months, 50 participants (32.9%) remained on study (22 pain and palliative care, 28 standard of care). Patients came off-study due to death or progression in disease, making them no longer eligible for the surgical oncology clinical trial they were enrolled in at the time of inclusion into this study. The randomization was successful at balancing the two groups in that there were no significant differences in demographic and self-reported measures between the two groups at baseline (Tables 1, 2).

Table 2.

Summary statistics for baseline and 24 h postop measures by treatment group

| Pain and palliative care |

Standard of care |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline age (years) | N = 76 | N = 76 |

| Mean (SD) | 52.43 (10.42) | 52.38 (3.01) |

| Min–max | 29–75 | 20–79 |

| Median | 51.5 | 53 |

| APACHE IIa postop | N = 75 | N = 70 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.05 (3.67) | 10.34 (3.05) |

| Min–max | 5–21 | 5–20 |

| Median | 10 | 10 |

| Pain intensity: baseline | N = 75 | N = 76 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.91 (4.34) | 2.95 (4.18) |

| Min–max | 0–15 | 0–16 |

| Median | 0 | 1 |

| Pain intensity: postop | N = 72 | N = 71 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.40 (4.53) | 6.83 (4.64) |

| Min–max | 0–19 | 0–17 |

| Median | 8 | 7 |

| Pain unpleasantness: baseline | N = 74 | N = 75 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.31 (4.34) | 3.28 (3.89) |

| Min–max | 0–16 | 0–13 |

| Median | 0 | 1 |

| Pain unpleasantness: postop | N = 71 | N = 70 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.73 (3.71) | 6.71 (3.86) |

| Min–max | 0–17 | 0–17 |

| Median | 6 | 7 |

| Symptom Distress Score: baseline | N = 76 | N = 76 |

| Mean (SD) | 22.42 (6.20) | 22.19 (6.62) |

| Min–max | 13–41 | 13–41 |

| Median | 21 | 21 |

| Symptom Distress Score: postop | N = 74 | N = 72 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.39 (6.65) | 28.37 (6.99) |

| Min–max | 16–45 | 16–48 |

| Median | 29 | 28 |

No statistically significant group mean differences

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II)—standard care (N = 69), early palliative care (N = 75)

Crossover from standard of care to pain and palliative care

If standard pain and symptom management were insufficient to meet the needs of a patient assigned to the standard of care group, study participants were permitted to crossover to the treatment arm of the study at the clinical discretion of the attending physician. Fifteen patients crossed over during the study, 1 by 24 h postop, 7 by 4–6 weeks, 3 by 3 months, and 4 by 6 months. A proportional hazards model was used to assess predictors of the risk of crossover. Table 3 shows that baseline CES-D was a significant predictor, where a higher CES-D score multiplied the crossover risk by 1.116 per point. Pain unpleasantness was also a significant predictor of crossover; a higher Gracely Pain Unpleasantness scale score multiplied the crossover risk by 1.365 per point. Diagnostic tests indicated that the predictors conformed to the proportional hazards assumption.

Table 3.

Proportional hazard model for time until crossover from standard of care to pain and palliative care

| Analysis of maximum likelihood estimates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DF | Parameter estimate | Standard error | Chi-square | P value | Hazard ratio |

| APACHE IIa | 1 | 0.02509 | 0.12079 | 0.0431 | 0.8354 | 1.025 |

| Depressionb | 1 | 0.10933 | 0.05492 | 3.9626 | 0.0465 | 1.116 |

| Pain intensityc | 1 | −0.19748 | 0.13152 | 2.2544 | 0.1332 | 0.821 |

| Pain unpleasantnessc | 1 | 0.31143 | 0.14082 | 4.8905 | 0.0270 | 1.365 |

| Symptom distressc | 1 | −0.01831 | 0.04673 | 0.1535 | 0.6952 | 0.982 |

Within 24 h postop,

at baseline (preop),

Time-varying covariate

Discontinuation from the study

We used a proportional hazards model to assess predictors of the risk of study discontinuation for any reason. Table 4 shows that crossover patients were likely to come off the study after switching treatment; the risk of discontinuation for crossover patients was over 2 times the risk of patients who remained in the standard of care group. Time-dependent CES-D (most recent score) was a significant predictor, multiplying the off-study risk by 0.96 per point. Symptom distress was also a significant predictor of discontinuation, a higher SDS score multiplied the off-study risk by 1.067. Diagnostic tests indicated that the predictors conformed to the proportional hazards assumption.

Table 4.

Proportional hazard model for time until study discontinuation

| Maximum likelihood estimates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DF | Parameter estimate | Standard error | Chi-square | P value | Hazard ratio |

| Treatment groupa | 1 | −0.30780 | 0.22998 | 1.7912 | 0.1808 | 0.735 |

| Crossoverb | 1 | 0.84766 | 0.41430 | 4.1862 | 0.0408 | 2.334 |

| APACHE IIc | 1 | −0.00684 | 0.03042 | 0.0506 | 0.8221 | 0.993 |

| Depressiona | 1 | −0.03805 | 0.01773 | 4.6059 | 0.0319 | 0.963 |

| Pain intensityb | 1 | 0.04402 | 0.04599 | 0.9165 | 0.3384 | 1.045 |

| Pain unpleasantnessb | 1 | −0.05507 | 0.05577 | 0.9751 | 0.3234 | 0.946 |

| Symptom distressb | 1 | 0.06457 | 0.01579 | 16.7151 | <.0001 | 1.067 |

At baseline (preop),

time-varying covariate,

within 24 h postop

Analysis of scales

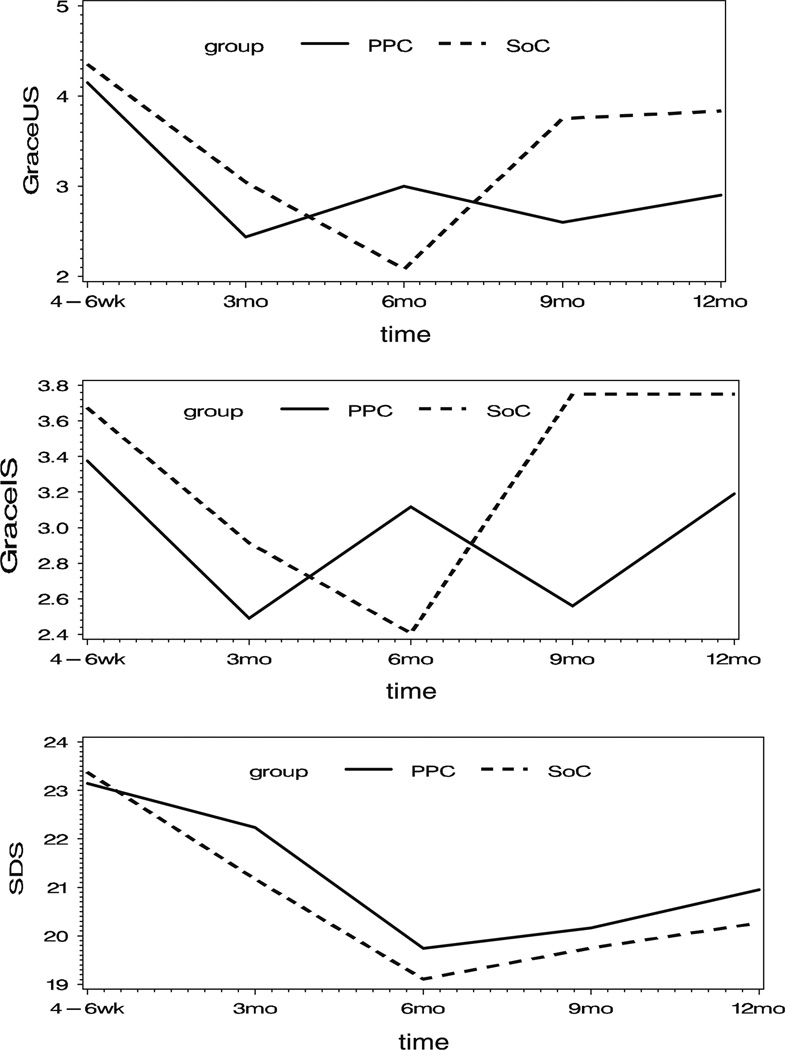

For the three scales, the patterns of mean scores over time by treatment group all suggest a quadratic function for time, as shown in Fig. 1. Thus, a quadratic function was fit to the data using a linear mixed model with a random effect for patient. These models also included fixed effects for assigned treatment group, preop baseline scale score, linear and quadratic time, time-varying CES-D score, and APACHE II score. Interaction terms for time by treatment, CES-D by treatment, and APACHE II score by treatment were included. A dropout pattern mixture was added to the model to account for potential bias attributable to self-selected study discontinuation. For the dropout pattern, three groups of discontinuers (for any reason) were identified, they are as follows: those discontinuing prior to the 3-month assessment (n = 45: pain and palliative care = 22, standard of care = 23), those discontinuing after the 3-month assessment but before the 12-month assessment (n = 57: pain and palliative care = 32, standard of care = 25), and those who completed the entire 12 months on study (n = 50: pain and palliative care = 22, standard of care = 28). A fixed effect for dropout group and interaction terms for dropout group with all other model terms were included in the model.

Fig. 1.

Mean scores versus time

Table 5 shows the contrasts in the adjusted means for the 3 scales at each measurement time for standard of care versus pain and palliative care by dropout groups, evaluated at the median baseline value for each scale, median CES-D, and median APACHE II scores. None of the estimated differences achieved statistical significance, although the study was not powered to detect more than what might be considered clinically meaningful differences. For the completers, the pain and palliative care group performs better at the end of the study versus their standard of care counterparts. The pattern of standard of care to pain and palliative care differences is not the same for the 3–9 month discontinuers compared with study completers.

Table 5.

Estimated standard of care—pain and palliative care difference by time point

| Dropout group | Assessment time | Pain intensity |

Pain unpleasantness |

Symptom distress |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | P value | Difference | P value | Difference | P value | ||

| Before 3 months | 4–6 weeks | −0.9989 | 0.9274 | 3.4215 | 0.1695 | 4.1578 | 0.2690 |

| 3–9 months | 4–6 weeks | 1.3665 | 0.1471 | 0.7825 | 0.3884 | −0.1489 | 0.9203 |

| 3 months | 1.5421 | 0.1356 | 0.5854 | 0.5510 | −1.5771 | 0.3172 | |

| 6 months | 0.1511 | 0.8934 | −0.4453 | 0.6747 | −2.1591 | 0.1963 | |

| 9 months | −2.8063 | 0.1906 | −2.3098 | 0.2312 | −1.8951 | 0.5009 | |

| Completers | 4–6 weeks | −0.8613 | 0.3351 | −0.9071 | 0.2888 | 0.6305 | 0.6740 |

| 3 months | −0.6056 | 0.5344 | −0.8970 | 0.3311 | 0.2031 | 0.8978 | |

| 6 months | −0.1008 | 0.9177 | −0.4522 | 0.6243 | 0.0695 | 0.9650 | |

| 9 months | 0.6531 | 0.4705 | 0.4273 | 0.6223 | −0.2294 | 0.8794 | |

| 12 months | 1.6561 | 0.1874 | 1.7416 | 0.1350 | 0.6830 | 0.7105 | |

Adjusted for preop score (baseline), APACHE II, and time-varying CES-D

Beyond exploring the quantitative differences between groups based on the results of patient-reported outcomes, in order to evaluate their individual physiologic and emotional experiences, participants in the early palliative care group were concurrently asked at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months “Can you describe how the Pain and Palliative Care Team has or has not provided you with support as you progress through your protocol treatment both while you’re here and when you return home?.” Three major themes emerged during thematic analysis of verbatim transcripts: (1) consistent communication to individualize care; (2) emotional support and “being there;” and (3) assistance with pain and symptom management (Table 6). Consistent communication was described in terms of the team as a whole and their focus on individualizing patients’ pain and comfort needs. When describing emotional support or “being there” participants emphasized the support and reassurance they felt knowing the Pain and Palliative Care Team was available across time. They saw team members as their advocates. Additionally, participants described positive personal experiences when it came to describing the team’s comprehensive and integrative management of their pain and symptoms both while at the NIH Clinical Center and once they went home.

Table 6.

Individual thematic quotes describing the palliative care team process and outcomes

| Theme | Individual quotes (gender, age, diagnosis) |

|---|---|

| (1) Consistent communication to individualize care | “The team was great, I mean they came in every day and at first it was kind of hard to answer their questions about the level of pain but they worked very hard to try to find the right combination of medicines and once they came up with a suggestion they were put into effect right away, which I was surprised. And once we got the right combination everything progressed very quickly, I got well much faster and was home within just a few days then.”—female, age 45, mesothelioma |

| “Actually just, I mean just having somebody talk to you about alternatives, not just medicine but alternatives to things like that, knowing that the group was there and that they cared enough to follow up with you and come and check with you and stuff like that, so if I had a problem I could call somebody. ”—male, age 49, mucinous adenocarcinoma | |

| (2) Emotional support or “being there” | “Well, they’ve never not been there for me, they’re always a phone call away. I have the business card right here. ”—male age 44, melanoma |

| “Helps to manage pain. Dr. B. is available to adjust the treatment even at home. The worked with me until the neurontin kicked in. ”—male, age 50, adenocarcinoma | |

| “They’re around to help you modify your routine to avoid symptoms. I’ve never needed to call them. ”—male, age 48, mesothelioma | |

| (3) Assistance with pain and symptom management | “They definitely supported me, it was really impressive I guess in the hospital to have members of the team check on me and sometimes in fact the whole team there at one time, which was impressive, but I just feel like as I said in answer to one of the other questions, that my experience here has been that they’ve been very concerned with the control of the pain as opposed to just saying here’s some medication, there’s been a lot of concern about is it working to make me as comfortable as possible. ”—female, age 50, ocular melanoma |

| “I have used them when I’ve returned home. Again, you know anxiety and insomnia which isn’t necessarily related to my pain and all. But certainly waking up and the music helped me relax and get back to sleep, I have used and it really was helpful to me. ”—female, age 45, colon cancer | |

| “During the time I was here during the surgery I was having a problem and they sent in an acupuncturist to try and relieve some of the discomfort I was having and they were visiting on a regular basis and based on the visits they will make more. ”—male, age 62, mesothelioma | |

| “Well today she gave us a phone number, and I guess I didn’t know before that I could call and talk to them. And I’d say my main concern has been the fact that I’m so tired all the time. And she talked to me about”—female, age 62, ocular melanoma |

Social support

Participants were asked “Who (or what) provides your strongest source of support to cope with your illness and related symptoms when you are at home?” at baseline, 4–6 weeks, and 6 months. Response options were partner/spouse, family member, friend, health professional, religious affiliation, and other with respondents able to select more than one source. Analyses included a count of the number of 5 options selected with “other” not included in the count. When the mean number of sources of support were compared, there was no difference between early palliative care and standard care groups at baseline (2.1 vs. 2.2, t = 0.64, P = .53) or at 6 months (means 1.8 and 1.9, respectively, t = 0.22, P = .83). However, there was a difference at 4–6 weeks with the mean number for the early palliative care group greater than the mean number for the standard group (2.1 vs. 1.5; t = 2.50, P = .014). At 4–6 weeks and again at 6 months, participants also were asked “Who (or what) provides your strongest source of support to cope with your illness and related symptoms when you are at the NIH Clinical Center?” The same response options were available and participants could check more than one source. There was no difference in the distributions of the number of sources identified between the early palliative care and standard care groups at either time.

As with the pain and symptom outcomes, we concurrently conducted a thematic analysis of verbatim transcripts for answers provided when participants in the early palliative care group were asked “Do you feel that you are more likely or less likely to complete the protocol (refers to primary clinical trial) knowing that the Pain Team and the Cancer team are working together? Can you put into words your sense of security?” Contrary to the quantitative measures of social support, which showed no difference except at 4–6 weeks between the participants receiving palliative care and those who did not, participants described their sense of support in terms of reassurance knowing that the Pain and Palliative Care Service was available and competent to provide care specifically focused on their physical and emotional comfort.

I would say probably more likely, I fully intend to go through the whole five years, I have no doubts that I would not do that just because I think it’s a good program and I’m very pleased with the care that I’m getting and appreciative that I am going to be followed so closely for 5 years. And that if anything should happen, that I would need more surgery or anything, that I know first of all I would be getting first rate medical care and then care as far as emotionally.

But pain is a big part of this protocol, I mean it’s a very painful surgery to go through and I know that it certainly made it a lot easier to get through the protocol because of the pain team’s involvement.

The majority of respondents described the cohesive nature between the primary clinical research team and the Pain and Palliative Care Team.

More likely (referring to completing the study protocol). I think they have a good relation between all the different groups.

More certain (referring to completing the study protocol) that they are because I guess as a group I feel that they all get together and they talk about things and decide things about how to handle it.

Discussion

As illustrated in these study results, the Pain and Palliative Care Service serves multiple clients (health care providers, investigators, patients, family members) while impacting the overall clinical care delivery system. There is evidence that patients and family often have conflicting expectations. These conflicting expectations are further compounded in when patients are enrolled in a clinical trial such as those in our study. Palliative care teams find negotiation critical in effective relationships between providers and patients. In order to optimize patient and family decision making, the overall goals of care must be defined [25]. For many patients and caregivers, it is the way they receive information that allows them to accept and act on it. Information received in a supportive way is experienced as a contribution to their overall well-being [10]. This sense of actively participating in dialogs regarding their symptom burden was evident in the perspectives the patients shared regarding the importance of communicating with the team, knowing the team was there for them and understanding that alternatives existed for optimizing their comfort in an individualized way.

It is unclear whether the lower pain intensity and unpleasantness scores (despite their greater symptom distress) for patients who remained on study through the 12 months were clinically meaningful when observed in isolation; however, when coupled with the patient’s perceptions that they had alternatives and resources for pain control both while they were at the clinical center and while they were at home because of their access to the pain and palliative care service, one begins to see the value that having ongoing care provided by integrated teams such as these may have.

Similar to Arnold’s [1] findings, our participants seemed to place emphasis on psychosocial and emotional needs in addition to their physiological needs when asked to describe the type and quality of their support both at home and when they were at the NIH Clinical Center. Arnold further explained that this focus on social relationships supports “belongingness” as a requisite human need that can increase at the end of life. Exploring how palliative care teams can optimize this need for belongingness through patients’ and families’ perspectives becomes particularly critical.

Conclusions

This study further supports the premise that palliative studies that use qualitative methods as an integral component of their design have shown that interpretation of data may be greatly facilitated because this triangulation of methods allows clinician researchers to explore both the process and the outcomes of overall care [14]. Palliative care research designs should continue to strive to embrace the same philosophies as the practice of palliative care: respect for patient autonomy, open awareness, holism, mutual respect, and collaboration [22, 42]. Mixed methods approaches that explore the patient and family experience by combining validated patient-reported outcome measures with open-ended qualitative methods offer the best hope for evaluating a full picture of palliative care outcomes from patient and family perspectives. These methods also provide a way for interdisciplinary integrative palliative care teams to explore the process and outcomes of their interventions and truly understand their patients’ and families’ experiences as they transition through to the end of life.

Abbreviations

- PPCS

Pain and Palliative Care Service

- NIH

Institutes of Health

- CC

Clinical Center

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- APACHE II

The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- GPS

Gracely Pain Scales

- SDS

Symptom Distress Scale

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Contributor Information

Gwenyth R. Wallen, Email: gwallen@cc.nih.gov, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Building 10, Room 2B14, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Karen Baker, Pain and Palliative Care Service, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive, 2-1733 MSC 1517, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Marilyn Stolar, United BioSource Corporation, 430 Bedford Street, Suite 300, Lexington, MA 02420, USA.

Claiborne Miller-Davis, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Building 10, Room 2B14, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Nancy Ames, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Building 10, Room 2B14, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Jan Yates, Shenandoah University, 348 Renaissance Drive, Martinsburg, WV 25403, USA.

Jacques Bolle, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 5207 Dorset Avenue, Chevy Chase, MD 20815, USA.

Donna Pereira, Palliative Care Department, George Washington University Hospital, 900 23rd St NW, Washington, DC 20037, USA.

Diane St. Germain, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 6130 Executive Boulevard, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Daniel Handel, Pain and Palliative Care Service, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive, 2-1733 MSC 1517, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Ann Berger, Pain and Palliative Care Service, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive, 2-1733 MSC 1517, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

References

- 1.Arnold BL. Mapping hospice patients” perception and verbal communication of end-of-life needs: An exploratory mixed methods inquiry. BMC Palliative Care. 2011;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(7):741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrera M. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(4):413–445. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr AJ, Higginson IJ. Measuring quality of life: Are quality of life measures patient centered? British Medical Journal. 2001;322:1357–1360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleeland CS. Cross-cutting research issues: A research agenda for reducing distress of patients with cancer. In: Foley KM, Gellband H, editors. Improving palliative care for cancer. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. pp. 233–276. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creswell JW, Zhang W. The application of mixed methods designs to trauma research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(6):612–621. doi: 10.1002/jts.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Bufalo C, Morelli A, Bassein L, Fasano L, Quarta CC, Pacilli AM, et al. Severity scores in respiratory intensive care: Apache ii predicted mortality better than saps ii. Respiratory Care. 1995;40(10):1042–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devery K, Lennie I, Cooney N. Health outcomes for people who use palliative care services. Journal of Palliative Care. 1999;15(2):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gracely RH, Dubner R, McGrath PA. Fentanyl reduces the intensity of painful tooth pulp sensations: Controlling for detection of active drugs. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1982;61(9):751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gracely RH, Kwilosz DM. The descriptor differential scale: Applying psychophysical principles to clinical pain assessment. Pain. 1988;35(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gracely RH, McGrath P, Dubner R. Ratio scales of sensory and affective verbal pain descriptors. Pain. 1978;5(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(78)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grande G, Todd CJ. Why are trials in palliative care so difficult? Palliative Medicine. 2000;14(1):69–74. doi: 10.1191/026921600677940614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: Reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychology. 1996;15(2):135–148. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higginson IJ. Evidence based palliative care. There is some evidence-and there needs to be more. BMJ. 1999;319(7208):462–463. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7208.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001;322(7297):1297–1300. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higginson IJ, Finlay I, Goodwin DM, Cook AM, Hood K, Edwards AG, et al. Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2002;23(2):96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchison C. Social support: Factors to consider when designing studies that measure social support. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(6):1520–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israel BA, Schurman SJ. Social support, control and the stress process. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson BS, Strauman J, Frederickson K, Strauman TJ. Long-term biopsychosocial effects of interleukin-2 therapy. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1991;18:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karim K. Conducting research involving palliative patients. Nursing Standard. 2000;15(2):34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger RA. Analyzing & reporting focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesage P, Portenoy RK. Ethical challenges in the care of patients with serious illness. Pain Medicine. 2001;2(2):121–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2001.002002121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, Shoaf SE, Smoller B, Dubner R. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(19):1250–1256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205073261904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzocato C, Sweeney C, Bruera E. Clinical research in palliative care: Patient populations, symptoms, interventions and endpoints. Palliative Medicine. 2001;15(2):163–168. doi: 10.1191/026921601668441770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McArthur JC, Yiannoutsos C, Simpson DM, Adornato BT, Singer EJ, Hollander H, et al. A phase II trial of nerve growth factor for sensory neuropathy associated with hiv infection. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1080–1088. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCorkle R, Cooley ME, Shea JA. A user’s manual for the symptom distress scale. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreno R, Apolone G, Reis Miranda D. Evaluation of the uniformity of fit of general outcome prediction models. Intensive Care Medicine. 1998;24(1):40–47. doi: 10.1007/s001340050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan DL. Computerized analysis. In: Krueger RA, editor. Analyzing & reporting focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Mara AM, Germain D, Ferrell B, Bornemann T. Challenges to and lessons learned from conducting palliative care research. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37(3):387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, McCarthy LJ, Friedlander-Klar H, Kiyasu E, et al. The memorial symptom assessment scale: An instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European Journal of Cancer Part A: General Topics. 1994;30(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarna L. Effectiveness of structured nursing assessment of symptom distress in advanced lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1998;25:1041–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarna L, Lindsey AM, Dean H, Brecht ML, McCorkle R. Nutritional intake, weight change, symptom distress, and functional status over time in adults with lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1993;20:481–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaver PR, Brennan KA. Measures of depression and loneliness. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Standing Medical Advisory Committee, & Committee. Standing Nursing and Midwifery Advisory. London: The principles and provision of palliative care; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor EJ. Factors associated with meaning in life among people with recurrent cancer. Onclology Nursing Forum. 1993;20:1399–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ternel JS, Greer JA, Musilkansky MA, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallen GR, Berger A. Mixed methods: In search of truth in palliative care medicine. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2004;7(3):403–404. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallen GR, Ulrich C, Grady C. Learning about a “Good Death”: Ethical considerations in palliative care nursing research. DNA Reporter. 2005;30(2):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wills TA, Shinar O. Measuring perceived and received social support. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 86–135. [Google Scholar]