Abstract

Psoriasis vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid (BP) represent two clinically well-characterized, chronic, inflammatory skin conditions. The concomitant occurrence of these two entities in a patient is rare. Here we report a 57-year-old male suffering from psoriasis vulgaris for 15 years on irregular medication who noticed eruption of blisters all over the body. We believe that this is the first case report of psoriasis vulgaris coexistent with bullous pemphigoid in Indian literature. Please check where you want bullous pemphigoid and where you want psoriasis pemphigoides.

Keywords: Methotrexate, bullous pemphigoid, salt split study

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic T-cell-mediated inflammatory disease affecting the skin and joints.[1] Psoriasis has been consistently associated with many cutaneous and systemic conditions. Recent epidemiological studies have shown that psoriasis patients are prone to develop cardiovascular and other metabolic syndromes.[2] On the other hand, a variety of cutaneous disorders may be associated with psoriasis.[3] Occurrence of autoimmune blistering disease in psoriasis is rare; here we report a case of coexistence of psoriasis with bullous pemphigoid (BP).

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old male presented with history of blisters all over the body of 10 days duration. They were associated with severe itching. The blisters were noticed first on the arm and later spread to other parts of the body. He also gave history of oral ulcers and difficulty in swallowing. The patient was a known case of psoriasis vulgaris since 15 years. He had used both modern medicines and alternative medicines for psoriasis for a variable amount of time; in particular, antipsoriatic treatment was discontinued 26 months before the presentation. Cutaneous examination revealed tense bullae and crusted erosions on upper and lower limbs [Figure 1]. Oral cavity showed erosions on the right side of buccal mucosa. Bulla spread sign and Nikolskiy's signs were negative.

Figure 1.

Multiple tense vesicles and bullae over the forearm.

There were hyperpigmented scaly plaques on the trunk, extremities and scalp. Blisters were present both over the scaly plaques as well as on the normal skin [Figure 2]. A diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris with BP was considered and he was investigated. His hematological and biochemical parameters were normal. The skin biopsy from scaly plaque was consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis and showed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, regular elongation of rete ridges. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin showed a strong linear basement membrane zone (BMZ) band with C3 and a weak BMZ band with IgG [Figure 3]; salt split study of skin biopsy (direct salt split) showed BMZ band on the epidermal side (‘roof pattern’) confirming the diagnosis of BP [Figure 4]. Indirect immunofluorescence using human skin as substrate showed linear BMZ band in serial dilutions of 1:10 and 1:80. Patient was treated with methotrexate 10 mg/week orally along with topical betamethasone in cream base (0.3%). At 1-month follow-up, psoriatic lesions have improved; he used to get occasional new blisters. At 3-month follow-up, both conditions have subsided with postinflammatory pigmentation.

Figure 2.

Hyperpigmented scaly plaques on the thighs; single bulla on the normal skin on the left thigh.

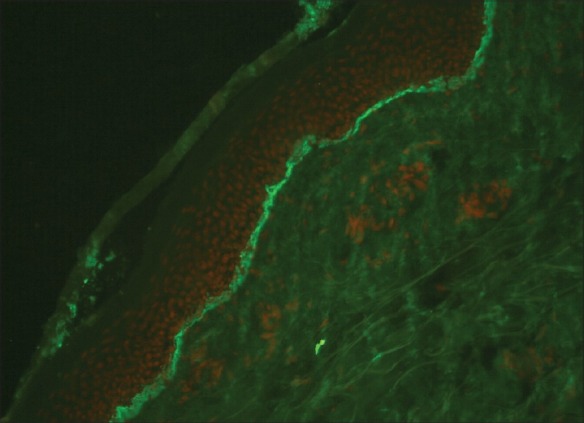

Figure 3.

Linear C3 basement membrane zone band (DIF, X20).

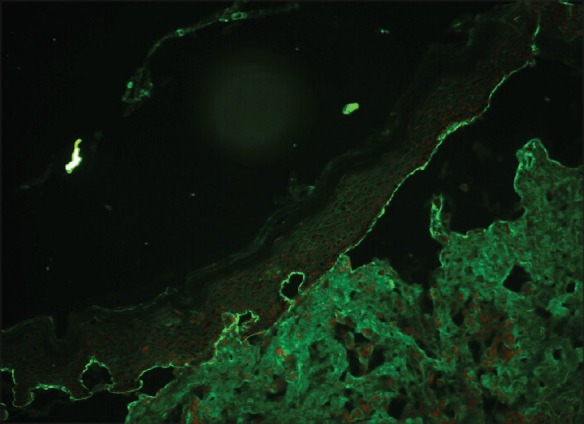

Figure 4.

Linear basement membrane zone band with IgG seen on the epidermal side of the salt split skin (DIF, X20).

DISCUSSION

Since the initial description of coexistence of bullous disease and psoriasis by Bloom in 1929, several autoimmune bullous diseases associated with psoriasis have been reported in literature.[4,5] These include pemphigus vulgaris (PV), pemphigus foliaceus (PF), pemphigus herpetiformis, bullous pemphigoid (BP), linear bullous dermatoses (LAD), cicatricial pemphigoid (CP), epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (psoriasis bullosa acquisita) and a novel bullous dermatoses targeting 200 kDa molecule present in the lower lamina lucida.[6–9] Among these, BP is the most frequent condition to be associated with psoriasis (psoriasis pemphigoides); less than 50 cases of such association have been described in the English literature. This association is reported to be more common among men than women with an average age of onset at 63 years. In most cases, psoriasis preceded the development of BP, with an average time interval of 20 years (range, 1–60 years) between the two conditions.[10]

The triggering factor in the association of psoriasis and BP remains unknown. Whether the treatment of psoriasis, pathological events at the basement membrane zone (BMZ) in psoriasis itself, common immunological or immunogenetic mechanisms, or a coincidence of multiple factors precipitates the autoimmune bullous diseases in these patients remain controversial.[11] Since the coexistence was seen in patients who received wide range of treatment for psoriasis as well as in untreated patients, it is difficult to incriminate a single agent as a potentially causative factor in the development of BP.[10] Reduced barrier function of the diseased psoriatic epidermis, combined with the irritant effects of therapies administered for psoriasis, such as anthralin, tar, and ultraviolet light, together with a low-grade immunologic BMZ insult, may precipitate blister formation.[7] Cram and Fukuyama demonstrated the triggering role of ultraviolet light B (UVB) in the induction of BP.[12] Psoralen and ultraviolet light A (PUVA) therapy is also known to induce blisters mimicking BP.[13] Recently, BP developing after efalizumab therapy for psoriasis has been described.[14] This molecule, however, has been withdrawn now from the market due to serious neurological side effects. Changes at the BMZ in psoriasis itself may be responsible for precipitating the bullous disease.[11] The presence of chronic inflammation, trafficking of activated lymphocytes and abundance of antigen presenting cells in psoriasis could unmask, expose or alter BMZ antigens, giving rise to autoantibody production.[15] Electron microscopy studies have shown a focal discontinuity and reduplication of the basal lamina in psoriasis. The concept of “epitope spreading” whereby tissue damage from a primary inflammatory process causes the release and exposure of a previously ‘sequestered’ antigen, leading to a secondary autoimmune response against the newly released antigen, may provide us with a unifying explanation for the development of subepidermal bullous disorders.[16]

Common immunogenetic or immunological mechanisms may also play a crucial role in this disease association. Psoriasis has been associated with other autoimmune diseases such as discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis, Crohns’ disease and ulcerative colitis. It may be suggested that psoriasis provides a particular predisposition of the immune system that, under certain circumstances leads to autoimmune response.[5] Circulating antibodies against components of the Malpighian layer and stratum corneum have been detected in the serum of psoriatic patients. The dysregulation of T-cell activity in psoriasis might result in the induction of specific antibodies to basement membrane antigens.[10] Psoriasis has been historically considered as Th1-type immune mediated disease. However, recent studies have established that Th17 is the primary pathogenetic subset; this subset of T cell also plays a key role in autoimmunity.[17]

Methotrexate has been used with good effect to treat BP-associated psoriasis. Steroids should not be used for the fear of triggering pustular psoriasis. Other drugs that have shown to be beneficial include dapsone, azathioprine, cyclosporine, erythromycin with etretinate.[11] We have treated our patient with methotrexate (10 mg per week). At 3-month follow-up both conditions responded well with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. We believe that this is the first case report of psoriasis vulgaris coexistent with BP in Indian literature.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Felice C, Chimenti S. Overview of Psoriasis. In: Chimenti S, editor. Psoriasis. Florence: See- Firenze; 2005. pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christophers E, Mrowietz U. Psoriasis. In: Burgdorf WH, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Landthaler M, editors. Braun- Falco's Dermatology. 3rd ed. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. pp. 506–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saraceno R, Chimenti S. Associated conditions of psoriasis. In: Chimenti S, editor. Psoriasis. Florence: See- Firenze; 2005. pp. 105–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom D. Psoriasis with superimposed bullous eruption. Med J Rec. 1929;130:246. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunwald MH, David M, Feuerman EJ. Coexistence of psoriasis vulgaris and bullous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:224–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endo Y, Tamiira A, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y, Hashimoto T. Psoriasis vulgaris coexistent with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:785–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnadas MA, Gilaberte M, Pujol R, Agustí M, Gelpí C, Alomar A. Bullous pemphigoid in a patient with psoriasis during the course of PUVA therapy: Study by ELISA test. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1089–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen KR, Shimizu S, Miyakawa S, Ishiko A, Shimizu H, Hashimoto T. Coexistence of psoriasis and an unusual IgG-mediated subepidermal bullous dermatosis: Identification of a novel 200-kDa lower lamina lucida target antigen. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:340–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris SD, Mallipeddi R, Oyama N, Gratian MJ, Harman KE, Bhogal BS, et al. Psoriasis bullosa acquisita. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:665–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilczek A, Sticherling M. Concomitant psoriasis and bullous pemphigoid: coincidence or pathogenic relationship? Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1353–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirtschig G, Chow ET, Venning VA, Wojnarowska FT. Acquired subepidermal bullous diseases associated with psoriasis: A clinical, immunopathological and immunogenetic study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:738–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cram DL, Fukuyama K. Immunohistochemistry of ultraviolet-induced pemphigus and pemphigoid lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:819–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomsen K, Schmidt H. PUVA-induced bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:568–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duong TA, Buffard V, André C, Ortonne N, Revuz J, Bagot M, et al. Efalizumab induced bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:161–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooke N, Jenkinson H, Wojnarowska F, McKenna K, Alderdice J. Coexistence of psoriasis and linear IgA disease in a patient with recent herpes zoster infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:643–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, Nishikawa T, Zone JJ, Black MM, et al. Epitope spreading: Lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Psoriasis. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. pp. 20.1–20.60. [Google Scholar]