Abstract

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a rare, locally invasive mesenchymal tumor occurring usually in women of reproductive age, which carries a high risk for local relapse; hence the need to differentiate it from the other mesenchymal tumors occurring in this region. We describe a case of a 44-year-old female presenting with a large pedunculated swelling on the right labia majora.

Keywords: Aggressive angiomyxoma, mesenchymal tumor, vulval tumor

INTRODUCTION

Aggressive angiomyxoma (AA) is a slow-growing vulvovaginal mesenchymal neoplasm with a marked tendency for local recurrence, but with a low tendency to metastasize. AA was first described by Steeper and Rosai in 1983.[1] It presents as a vulval polyp clinically and is diagnosed on histology. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are commonly found in AA.[2] It is thus likely to grow during pregnancy and respond to hormonal manipulation. It involves mainly the pelvis, vulva, perineum, vagina and urinary bladder in adult women in the reproductive age. Considering its locally aggressive nature, appropriate management and long-term follow-up is necessary. Many options for the treatment of recurrences have been tried with varying success, but no single modality is clearly beneficial over others.

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old female with human immunodeficiency virus infection of four years duration presented with a slow-growing mass on the right labia majora since three years. She presented to us due to ulcerations that developed on the swelling since 10 days that was associated with a clear discharge. Local examination showed a well-circumscribed pedunculated polypoidal mass measuring 16 cm × 10 cm. The mass was non-tender, soft and spongy in consistency. The overlying ulcer measured 5 cm × 1.5 cm over the dependent part, with the floor covered by unhealthy pale granulation tissue [Figure 1]. The inguinal lymph nodes were not enlarged. Her blood investigations and sonography of the abdomen revealed no abnormality. Sonography of the local part showed a large mass with peripheral vascularity, heterogenous hyperechoic areas, thick echoes and non-vascular areas in the center. There was a cystic area of size 2.8 × 2.2 near the stalk. Fine needle aspiration cytology smears revealed only blood without cellular elements. The patient was referred to gynaecology services for excisional biopsy of the lesion considering a diagnosis of fibroepithelial polyp, a vulval fibroma or a giant acrochordon. She underwent a local excision of the tumor with ligation of the stalk [Figure 2]. There was profuse bleeding during the procedure. On histopathology, the tumor was composed of spindle and stellate-shaped cells in a myxoid matrix [Figure 3]. These cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm and lacked significant nuclear pleomorphism and mitosis. Also seen were variable-sized thin-walled capillaries and thick-walled vascular channels. Some of these vessels showed perivascular hyalinization of their vascular walls [Figure 4]. This was suggestive of AA.

Figure 1.

A well-defined polypoidal pedunculated measuring 16 cm × 10 cm with an attached stalk and overlying skin showing an ulcer measuring 5 cm × 1.5 cm over the dependent part

Figure 2.

After surgical excision of the tumor mass with a small part of stalk left behind

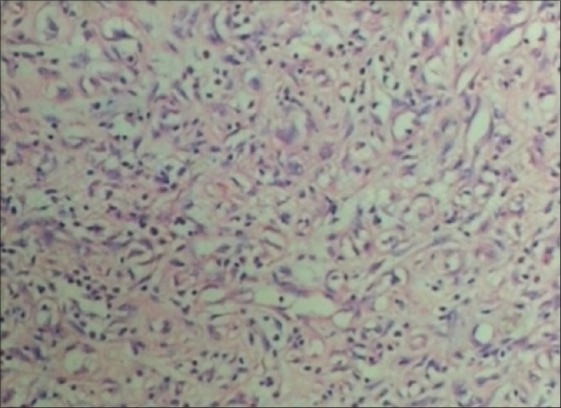

Figure 3.

Tumor composed of spindle- and stellate-shaped cells in a myxoid matrix (H and E ×10)

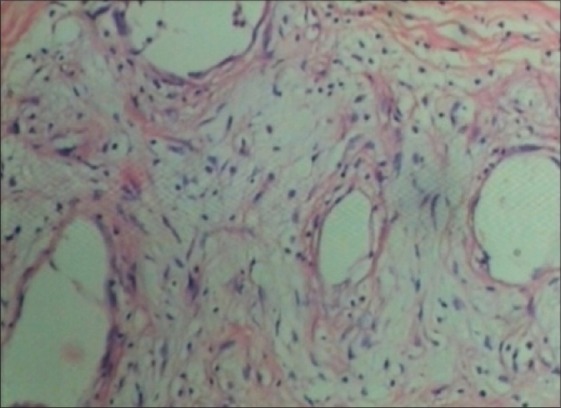

Figure 4.

Showing thin- and thick-walled vessels lined by spindle- and stellate-shaped cells (H and E ×40)

DISCUSSION

Angiomyxomas are classified either as superficial (also called as cutaneous myxoma) or AA. Superficial angiomyxomas usually present in middle-aged adults as a single nodule or a polypoidal lesion in the head and neck region that may be clinically confused with skin tag or neurofibroma. The stroma is made up of mostly edema with little myxoid material. On the other hand, AA occurs almost exclusively in the pelvic and perineal regions of women of reproductive age, but is occasionally reported in men (male-to-female ratio 1:6).[2] The term “aggressive” denotes its propensity for local aggression and recurrences after excision. Usually, this tumor is non-metastasizing, but there are reports of multiple metastases in women treated initially by excision and who later succumbed to metastatic disease.[3,4] About one-fourth of these tumors are pedunculated. There is no complete consensus regarding the tumor pathogenesis. This hormonally responsive tumor is believed to arise from specialized mesenchymal cells of the pelvic–perineal region or from the multipotent perivascular progenitor cells, which often display variable myofibroblastic and fibroblastic features.[5] This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the tumor cells express desmin and, in some cases, a smooth muscle actin along with desmin. Recent cytogenetic and molecular studies have identified a variety of genetic alterations, involving the chromosome 12, in the region 12q13-15. A gene in this region, called high-mobility group protein isoform I-C (HMGIC), which encodes proteins involved in the transcriptional regulation, appears to have a role in the pathogenesis of this tumor. Detection of inappropriate HMGI-C expression using the immunoperoxidase technique with anti HMGI-C antibody may potentially be a useful marker for microscopic residual disease.[6]

Clinically, AA may be misdiagnosed as Bartholin cyst, lipoma, labial cyst, Gartner duct cyst, levator hernia or sarcoma. Fibro-epithelial stromal polyp, superficial angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, cellular angiofibroma and smooth muscle tumors also need to be considered in the differential diagnoses of a polypoidal mass in the perineum. AA is an infiltrative tumor, whereas angiomyofibroblastoma is well circumscribed (this characteristic can also be identified on magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). Also, AA has thick-walled vessels, which are less numerous than the thin-walled vessels in angiomyofibroblastoma. On computed tomography (CT) scan, these tumors have a well-defined margin with attenuation less than that of the muscle. On MRI, these tumors show high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. The attenuation on CT and high signal intensity on MRI are likely to be related to the loose myxoid matrix and high water content of angiomyxoma.[7] Our patient was not subjected to radiological investigation as its clinical appearance at presentation was that of a benign polyp. Wide surgical excision is the traditional treatment of choice. However, organs, such as the rectum and bladder to which the tumor may be attached, are spared as the morbidity of extensive surgery may not be justified due to its high recurrence rate even after complete resection. Where fertility is to be preserved or surgery is likely to be extensive and mutilating, incomplete resection is acceptable as local recurrences can be treated with further resection.[7] Recurrences may occur from months to several years after excision (2 months to 15 years).[8] AA, despite the name, is not that aggressive, with only a 30% chance of recurrence, which is eminently treatable by excision with a 1 cm margin. Most of the patients have only one recurrence. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are considered less-suitable options due to low mitotic activity. Hormonal manipulation with tamoxifen, raloxifene and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues has been shown to reduce the tumor size and may help to make complete excision feasible in large tumors and in the treatment of recurrence.[9] Angiographic embolization may also help in subsequent resection by shrinking the tumor as well as making it easier to identify it from surrounding normal tissues.[10] As late recurrences are known, all patients need to be counselled about the need for long-term follow-up. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred method for detecting recurrences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steeper TA, Rosai J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:463–75. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han-Geurts IJ, van Geel AN, van Doorn L, den Bakker M, Eggermont AM, Verhoef C. Aggressive angiomyxoma: Multimodality treatments can avoid mutilating surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:1217–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siassi RM, Papadopoulos T, Matzel KE. Metastasizing aggressive angiomyxoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;2:1772. doi: 10.1056/nejm199912023412315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blandamura S, Cruz J, Faure-Vergara L, Machado-Puerto I, Ninfo V. Aggressive angiomyxoma: A second case of metastasis with patient's death. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1072–4. doi: 10.1053/s0046-8177(03)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alameda F, Munne A, Baro T, Iglesias M, Condom E, Lloreta-Trull J, et al. Vulvar angiomyxoma, aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma: An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:193–205. doi: 10.1080/01913120500520911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nucci MR, Fletchr CD. Vulvovaginal soft tissue tumors: Update and review. Histopathology. 2000;36:97–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Outwater EK, Marchetto BE, Wagner BJ, Siegelman ES. Aggressive angiomyxoma: Findings on CT and MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:435–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behranwala KA, Thomas JM. Aggressive angiomyxoma: A distinct clinical entity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:559–63. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(03)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCluggage WG, Jamieson T, Dobbs SP, Grey A. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: Dramatic response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:623–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magtibay PM, Salmon Z, Keeney GL, Podratz KC. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum: A case series. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]