This article reports on the outcomes of patients with cancer who are treated with vancomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections.

Keywords: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteremia, Bloodstream infections, Vancomycin

Abstract

Background.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSIs) can cause significant morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer. However, data on outcomes of patients treated with vancomycin are lacking.

Methods.

We identified 223 patients with cancer who developed MRSA BSIs between January 2001 and June 2009 and were treated with vancomycin. Treatment failure was defined as death within 60 days of infection, persistent bacteremia ≥5 days, fever ≥4 days, recurrence or relapse, and secondary MRSA infection.

Results.

The treatment failure rate was 52% (116 of 223 patients). These patients were more likely to have been hospitalized, been treated with steroids within the previous 3 months, developed acute respiratory distress syndrome, required mechanical ventilation, required intensive care unit care, and community-onset infections (all p < .05). Risk factors for MRSA-associated mortality (27 of 223 patients; 12%) included hematologic malignancy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, community-onset infection, secondary BSI, MRSA with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≥2.0 μg/mL, mechanical ventilation, and a late switch to an alternative therapy (≥4 days after treatment failure; all p < .05). On multivariate analysis, mechanical ventilation and recent hospitalization were identified as independent predictors of vancomycin failure, and community-onset infection, secondary BSIs, and MIC ≥2 μg/mL were identified as significant predictors of MRSA-associated mortality.

Conclusions.

We found a high treatment failure rate for vancomycin in patients with cancer and MRSA BSIs, as well as a higher mortality. A vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL was an independent predictor of MRSA-associated mortality. An early switch to an alternative therapy at the earliest sign of failure may improve outcome.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is known to cause serious infections that can involve the skin, soft tissues, lungs, cardiac valves, and bloodstream. It is a major cause of community-onset and hospital-acquired bloodstream infections (BSIs) globally [1–3]. Its ability to produce metastatic or secondary infections such as endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis has been documented in myriad studies [4–7]. The emergence and global spread of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) constitutes one of the most serious contemporary challenges in the treatment of community- and health care-acquired infections. Of all MRSA infections, pneumonia and BSIs may be the most aggressive and difficult to treat; they are usually associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Until recently, the mainstay therapy for MRSA infections was vancomycin, administered at the dosage necessary to achieve serum trough concentrations of 15–20 μg/mL [8]. However, many studies reported treatment failures of vancomycin for infections caused by MRSA strains, mainly in immunocompetent patients, with apparent in vitro susceptibility but with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2 μg/mL [9, 10] and despite the achievement of the recommended serum trough concentrations [11, 12]. As per the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) 2011 recommendations [13], for isolates with a vancomycin MIC ≤2 μg/mL, clinical response should be used to determine whether vancomycin use should continue. Alternative therapy has been recommended when the vancomycin MIC is >2 μg/mL [13]. On the other hand, the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases guidelines recommend alternative therapy when the MIC is >1.5 μg/mL [14]. Furthermore, favorable outcomes have emerged for the use of daptomycin and linezolid for MRSA BSIs and hospital-acquired pneumonia, respectively [15, 16]; thus, initial therapy with these agents for the above indications may be contemplated.

S. aureus infections such as BSIs, endocarditis, and surgical site infections can cause significant morbidity [17] and mortality in patients with cancer [18–21]. In addition, factors such as sepsis and comorbid conditions have been associated with increased MRSA-associated mortality in patients with cancer [22]. On the other hand, scarce data exist on vancomycin treatment outcomes or risk factors for treatment failure and MRSA-associated mortality in patients with cancer and MRSA BSIs. Thus, in this study, we determined the characteristics and outcomes of MRSA BSIs in patients with cancer who were treated with vancomycin over 9 years at a single institution.

Patients and Methods

In this retrospective study, we searched the infection control database at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, to identify all patients with cancer who were diagnosed with MRSA BSIs from January 1, 2001 to June 30, 2009. The predetermined inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) treatment for any type of malignancy at MD Anderson; (b) MRSA isolated from blood cultures between January 1, 2001 and June 30, 2009; and (c) treatment with vancomycin for more than 72 hours.

A waiver of informed consent and a waiver of authorization were requested because the study used retrospective data review that involved no diagnostic or therapeutic intervention, as well as no direct patient contact. The institutional review board approved the request and the protocol.

All definitions were developed before the initiation of the study. Treatment failure was defined as any of the following: (a) death within 60 days of infection and treatment for MRSA BSI (in-hospital mortality); (b) fever ≥4 days during therapy; (c) persistent bacteremia ≥5 days; (d) relapse or recurrence of MRSA BSI within 30 days of discontinuation of primary therapy; (e) secondary MRSA infection after bacteremia; or (f) early discontinuation or switch to an alternative therapy because of relapse, recurrence, or grade 3 or 4 adverse events. If patients met more than one criterion, the outcome was classified as one failure.

Sepsis was defined as any two of the following: (a) heart rate >90 beats per minute; (b) respiratory rate >20 per minute; (c) temperature >38°C or <36°C; and (d) white blood cell count >12,000/μL, <4,000/μL, or >10% bands. Severe sepsis was defined as presence of hypotension responsive to fluid resuscitation in patients with sepsis. Relapse was defined as MRSA BSI within 1 month after therapy. Recurrence was defined as recurrent MRSA BSI while on therapy and after documentation of negative blood cultures.

A catheter-related BSI was defined as a BSI in patients with intravascular catheters and at least one positive blood culture for MRSA obtained from a peripheral vein, a clinical manifestation of infection (i.e., fever, chills, or hypotension), and no apparent source of the BSI except the catheter. In addition, one of the following was required: a positive semiquantitative (>15 colony-forming units [CFUs]/catheter segment) or quantitative (>102 CFUs/catheter segment) culture in which the same organism (species and antibiogram) was isolated from the catheter segment and peripheral blood; simultaneous quantitative blood cultures with a ≥3:1 ratio for catheter versus peripheral blood; or a differential period of catheter culture versus peripheral blood culture positivity of >2 hours [23].

Clinical treatment success was defined as negative blood cultures for MRSA and resolution of signs and symptoms of infection by day 60, as assessed by the principal investigator.

Data Collection

Information was collected for several variables, including demographics (age, sex, and ethnicity), underlying cancer, risk factors for MRSA BSI (i.e., prior hospitalization, antibiotic exposure within 3 months of therapy, history of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus or MRSA infection within 1 year, comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), microbiological data, immune function (i.e., neutrophil count), neutropenia duration, concomitant immunosuppressive medications, antimicrobial therapy, and clinical and microbiological outcomes. In addition, we recorded the dates and times of blood cultures and the Etest (bioMerieux, Inc., Durham, NC) was used to determine vancomycin MICs, as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were provided for relevant demographic, clinical, and therapeutic variables. Vancomycin treatment success and failure were compared, with regards to the distribution of each variable, using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ .05. To determine the independent predictors of vancomycin failure, we performed a backward stepwise logistic regression analysis. The variables considered for model inclusion a priori were those associated with vancomycin failure on univariate analysis, with p < .1.

In the mortality analysis, we calculated treatment response and mortality rates. We compared MRSA-associated death and MRSA survival with respect to each variable. A p value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify the demographic, clinical, and therapeutic factors associated with MRSA-associated mortality. The variables selected for the regression models included all variables with p < .1 on univariate analysis. A backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed, using the significant variables to identify the independent predictors of MRSA-associated mortality. A comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival of patients with MRSA BSIs was performed using the log-rank statistic. This analysis was stratified by MIC ≥2 μg/mL and MIC <2 μg/mL. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was plotted. All calculations were computed using STATA 10 statistical software (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

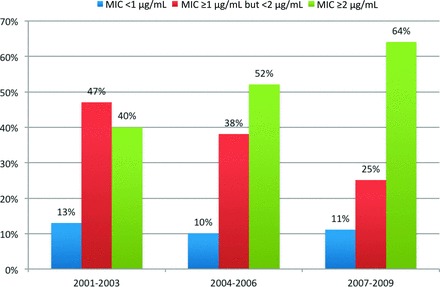

We identified 250 patients with MRSA BSIs. Twenty-seven were excluded because of nonevaluable outcome. Discrete vancomycin MIC values were available for all MRSA isolates during the study period because our microbiology laboratory uses the Etest to determine MICs for isolates cultured from sterile sites (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of minimum inhibitory concentrations over time for the clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Abbreviation: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

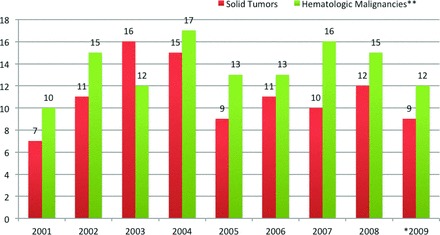

Figure 2 shows a yearwise distribution of the 223 patients in the study population on the basis of underlying cancer type: 100 solid tumors (45%) versus 123 hematologic malignancies (55%). More patients were seen in 2003 and 2004 than in 2001, 2002, or 2005–2009.

Figure 2.

Yearwise distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections in patients with solid tumors versus hematologic malignancies from 2001 to 2009. *Cases between January 1, 2009 and June 30, 2009. **Includes patients with lymphoma or leukemia, as well as hematopoeitic stem cell transplant recipients.

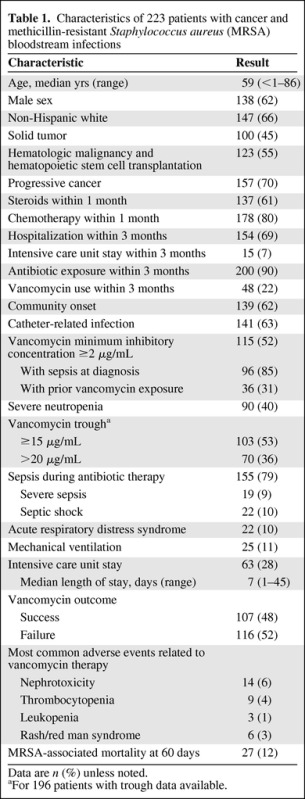

Patients' characteristics are shown in Table 1. Median age was 59 years (range, 1 month to 86 years); 138 (62%) were male and 147 (66%) were non-Hispanic white. Steroid and chemotherapy use within 1 month of infection was noted for 137 (61%) and 178 (80%) patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 223 patients with cancer and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections

Data are n (%) unless noted.

aFor 196 patients with trough data available.

A total of 139 (62%) patients had community-onset MRSA BSIs; 141 (63%) cases were catheter related. In all, 196 patients (88%) presented with sepsis-like symptoms and 90 patients (40%) had severe neutropenia.

Vancomycin Treatment Outcome

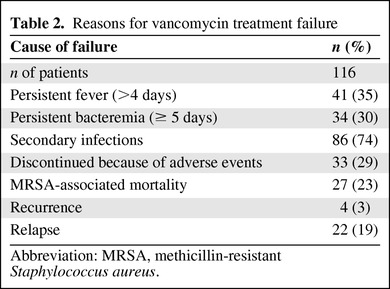

More than half of the patients experienced failure to initial vancomycin therapy (116 patients; 52%). The reasons for failure are shown in Table 2. Secondary MRSA infections were seen in 86 patients (74%) and included pneumonia (14 patients), septic thrombophlebitis (20 patients), infective endocarditis (6 patients), and deep tissue abscesses (11 patients). Persistent fever occurred in 41 patients (35%) and discontinuation of vancomycin because of adverse events occurred in 33 patients (29%). Adverse events, as documented in Table 1, included nephrotoxicity (14 patients), thrombocytopenia (9), red man syndrome/rash (6), leukopenia (3) and others (4). Few patients had more than one adverse event.

Table 2.

Reasons for vancomycin treatment failure

Abbreviation: MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

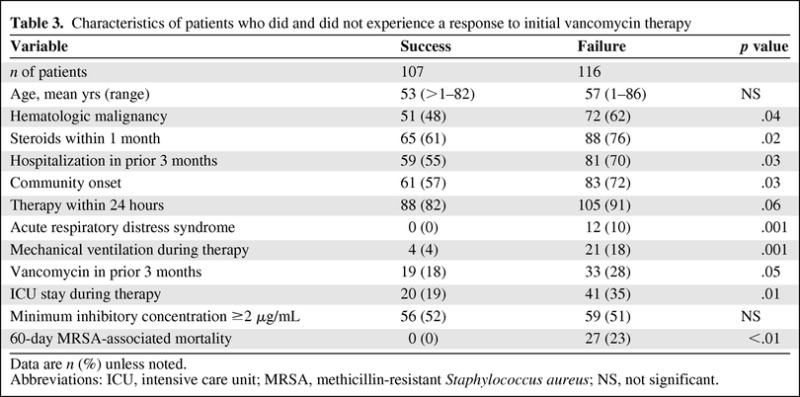

Patients who did not experience a response to vancomycin were more likely to have hematologic malignancies, community-onset BSI, or acute respiratory distress syndrome; have received steroids within 1 month of diagnosis or vancomycin within 3 months of diagnosis; have been hospitalized within 3 months of diagnosis; had needed mechanical ventilation during therapy; or had been in the intensive care unit (ICU) during therapy (all p < .05; Table 3). Furthermore, the MRSA-associated mortality rate within 60 days of diagnosis was much higher in patients who did not experience a response to initial vancomycin therapy (23% vs. 0%; p < .01).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients who did and did not experience a response to initial vancomycin therapy

Data are n (%) unless noted.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NS, not significant.

A multivariate logistic regression model revealed the joint effects of covariates as predictors of vancomycin treatment failure. Mechanical ventilation (odds ratio [OR] = 5.7, confidence interval [CI] = 1.92–20; p = .02) and hospitalization within 3 months of BSI (OR = 2.1, CI = 1.13–3.85; p = .03) were found to be significantly associated with vancomycin failure.

Switch to Alternative Antibiotics

Of the 116 patients who did not experience a response to vancomycin, 43 (37%) were switched to other antibiotics, including monotherapy with daptomycin (18), linezolid (10), and tigecycline (8) or in different combination of these antibiotics (7). All MRSA isolates were susceptible to these antibiotics. Among these patients, an early switch (≥4 days) was associated with no MRSA-associated mortality versus a 22% mortality rate for patients who were switched late (>4 days; p < .001). There were similar proportions of MRSA isolates with MIC ≥2 μg/mL between the two groups. Interestingly, variations in vancomycin MIC were minimal (±0.5 μg/mL) for patients who had MRSA isolates recovered while undergoing vancomycin therapy or for patients who had relapsed or recurrent MRSA infections and received alternative therapy.

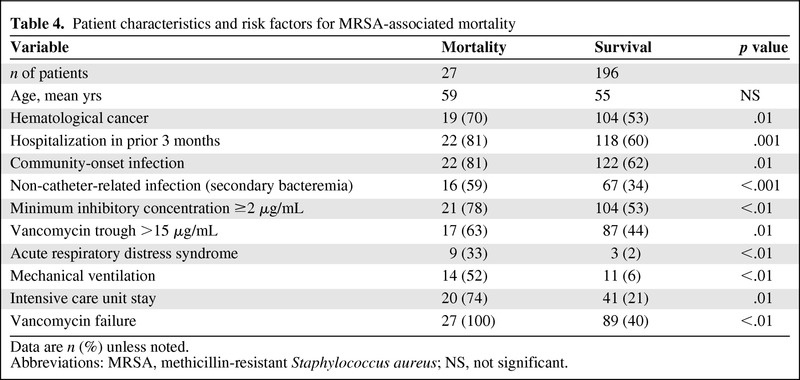

MRSA-Associated Mortality

In all, 27 patients died with MRSA infections (12%; Table 4). Underlying hematologic malignancies, hospitalization within 3 months of diagnosis, community-onset BSI, secondary BSI, ICU stay, mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL, and high vancomycin failure rates were associated with MRSA-associated death (all p < .05). A multivariate logistic regression model revealed the joint effects of covariates as predictors of MRSA-associated mortality: community-onset infection (OR = 3.3; CI = 1.12–9.09; p = .04), secondary BSI (OR = 3.2, CI = 1.32–7.2; p = .03), and vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL (OR = 2.7, CI = 1.02–7.09; p = .05) were significantly associated with mortality within 60 days of diagnosis. A vancomycin MIC of ≥2 μg/mL was also associated with prior vancomycin exposure and sepsis at diagnosis (p = .04 and .05, respectively).

Table 4.

Patient characteristics and risk factors for MRSA-associated mortality

Data are n (%) unless noted.

Abbreviations: MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NS, not significant.

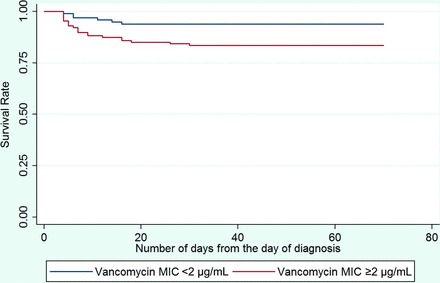

Survival Analysis of Patients with MRSA BSIs

Figure 3 depicts the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients with MRSA BSIs, stratified by MIC values (MIC ≥2 μg/mL vs. <2 μg/mL). More deaths were seen in patients with MIC values of ≥2 μg/mL (log-rank test value, p = .02). We found no statistical difference in the median survival durations of these populations. We attribute this finding to a bimodal temporal mortality distribution in patients with MIC ≥2 μg/mL versus a uniform distribution in patients with MIC <2 μg/mL.

Figure 3.

Survival curves of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections stratified by minimum inhibitory concentrations ≥2 μg/mL versus p = .02). Abbreviation: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate, in depth, the characteristics and outcomes of patients with cancer and MRSA BSIs, with a focus on clinical outcomes after vancomycin therapy. Our study, which included 223 patients treated at a single institution over the span of 9 years, yielded important findings: (a) a high rate of vancomycin treatment failure in patients with cancer as based on predetermined definitions of failure; (b) a significant association exists between mortality rates and a vancomycin MIC of ≥2 μg/mL; and (c) switching to an alternative therapy ≤4 days after vancomycin treatment failure is associated with a higher survival rate.

Vancomycin treatment failure was observed in 52% of patients in our study. A similar failure rate was reported in a recent retrospective single-center study of 320 patients [24] with documented MRSA BSIs who were initially treated with vancomycin between 2005 and 2010. However, the authors defined vancomycin failure as 30-day mortality or persistent signs and symptoms of infection after therapy and persistent BSI ≥7 days. Furthermore, in a logistic regression model, they identified infective endocarditis, nosocomially acquired infection, initial vancomycin trough <15 μg/mL, and vancomycin MIC of >1 μg/mL, as determined by an Etest, as predictors of treatment failure. In comparison, an MIC >1 μg/mL was not a significant predictor of treatment failure in our study. On the other hand, with a lack of standardized definitions for success and failure in these kinds of studies, comparisons of outcomes and even risk factors or predictors may be inappropriate.

In a recent cohort study by Lubin et al. [25], the variables associated with a vancomycin MIC of ≥2 μg/mL included age >50 years, prior vancomycin exposure, MRSA BSI history, chronic liver disease history, and nontunneled central venous catheter use. In our study, MRSA with a vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL was associated with prior vancomycin exposure and sepsis at diagnosis. In addition, our data showed that an MIC of ≥2 μg/mL was associated with an increase in MRSA-associated mortality but not with vancomycin treatment failure. These findings are consistent with those of studies by Sorieno et al [2] and Lodise et al., [26] except in those studies, a high MIC (≥2 μg/mL) was associated with treatment failure. Several other recent studies have demonstrated poor outcomes (in terms of mortality) in patients with MRSA infections and vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL. [27–29] The high failure rate and mortality in these patients may be due to the presence of unsuspected heteroresistant vancomycin S. aureus, which can be prevalent in MRSA isolates with MIC ≥2 μg/mL [27, 28]. Another important factor that may affect mortality is the presence of the panton valentine leukocidin gene. However, in a recent study at our institution, the presence of this gene was not associated with a poor outcome in patients with cancer and MRSA infections [30].

On the basis of our findings, an alternative agent to vancomycin should be considered for MRSA with vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL. Moreover, the IDSA 2011 recommendations for vancomycin MIC >2 μg/mL include the use of appropriate alternative therapy [13]. Previous studies have made similar recommendations, but with MIC values of >1 μg/mL and a target vancomycin trough serum value of >10 μg/mL [2, 9, 10]. In a prospective cohort study by Hidayat et al [12], 95 patients with MRSA with a vancomycin MIC ≥2 μg/mL had a lower clinical response rate than did those with an MIC of <2 μg/mL, after controlling for the targeted trough.

Interestingly and similar to our findings, Holmes et al. [31] found that higher vancomycin MIC was associated with increased mortality; however, it was regardless of the usage of vancomycin or flucloxacillin. The authors theorized that treatment outcome might have been affected by additional unrecognized host or pathogen factors. The design of our study precluded this kind of comparison because we included only patients who received vancomycin as initial therapy for MRSA BSI and excluded patients with MSSA bacteremia.

As highlighted by Holland and Fowler [32], various studies showed some relationship between vancomycin MIC and high failure rate or mortality, but the link between the two is probably not causal. Although the guidelines may differ regarding at which level of MICs an alternative therapy should be considered and for which MRSA infections (and despite the limitations of our findings), we recommend the cautious use of vancomycin in severe (life-threatening) staphylococcal diseases as recommended by others as well [33]; alternative therapy should be considered if the vancomycin MIC is ≥2 μg/mL, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Patients who were switched earlier to an alternative anti-MRSA agent (within 4 days) because they did not experience a response to vancomycin had much lower mortality rates, indicating the crucial timing of empiric “optimal” therapy for serious infections in immunocompromised patients in particular. Various studies have found that daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline are important substitutes for vancomycin, depending on the site of infection [15, 34–37]. In one study, daptomycin and linezolid were recommended for managing severe community- or hospital-acquired infections [38].

Our study has some inherent limitations, including its retrospective nature. However, it includes a large number of patients treated with the same initial antibiotic over the span of 9 years. Furthermore, relevant cofounders could have been overlooked, and the complexity of our immunocompromised patients may make the determination of causality difficult.

In summary, we found a high failure rate for vancomycin in MRSA BSI in patients with cancer, with increased morbidity and mortality. Switching to an alternative therapy at the earliest sign of failure (≤4 days) may improve outcome. We also recommend alternative anti-MRSA therapy in patients with cancer with serious MRSA infections with a vancomycin MIC of ≥2 μg/mL.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cubist Pharmaceuticals. We thank Ann M. Sutton from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for editorial support.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Roy F. Chemaly

Provision of study material or patients: Roy F. Chemaly

Collection and/or assembly of data: Sminil N. Mahajan, Jharna N. Shah

Data analysis and interpretation: Sminil N. Mahajan, Jharna N. Shah, Roy F. Chemaly

Manuscript writing: Sminil N. Mahajan

Final approval of manuscript: Ray Hachem, Frank Tverdek, Javier A. Adachi, Victor Mulanovich, Kenneth V. Rolston, Issam I. Raad, Roy F. Chemaly

References

- 1.Steinberg JP, Clark CC, Hackman BO. Nosocomial and community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremias from 1980 to 1993: Impact of intravascular devices and methicillin resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:255–259. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soriano A, Martinez JA, Mensa J, et al. Pathogenic significance of methicillin resistance for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:368–373. doi: 10.1086/313650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) report, data summary from October 1986-April 1996, issued May 1996. A report from the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system. Am J Infect Control. 1996;24:380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler VG, Jr., Sanders LL, Sexton DJ, et al. Outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia according to compliance with recommendations of infectious diseases specialists: Experience with 244 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:478–486. doi: 10.1086/514686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mylotte JM, McDermott C, Spooner JA. Prospective study of 114 consecutive episodes of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:891–907. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen AG, Wachmann CH, Espersen F, et al. Treatment and outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A prospective study of 278 cases. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:25–32. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falcone M, Carfagna P, Cassone M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus sepsis in hospitalized non neutropenic patients: Retrospective clinical and microbiological analysis. Ann Ital Med Int. 2002;17:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheetz MH, Wunderink RG, Postelnick MJ, et al. Potential impact of vancomycin pulmonary distribution on treatment outcomes in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:539–550. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakoulas G, Moise-Broder PA, Schentag J, et al. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2398–2402. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2398-2402.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moise-Broder PA, Sakoulas G, Eliopoulos GM, et al. Accessory gene regulator group II polymorphism in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is predictive of failure of vancomycin therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1700–1705. doi: 10.1086/421092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moise PA, Smyth DS, El-Fawal N, et al. Microbiological effects of prior vancomycin use in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:85–90. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hidayat LK, Hsu DI, Quist R, et al. High-dose vancomycin therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: Efficacy and toxicity. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2138–2144. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children (2011) Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18–55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dryden M, Andrasevic AT, Bassetti M, et al. A European survey of antibiotic management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: Current clinical opinion and practice (2010) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(Suppl 1):3–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler VG, Jr., Boucher HW, Corey GR, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:653–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walkey AJ, O'donnell MR, Wiener RS. Linezolid vs glycopeptide antibiotics for the treatment of suspected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2011;139:1148–1155. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chemaly RF, Hachem RY, Husni RN, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus surgical-site infections in patients with cancer: A case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1499–1506. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0923-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang CI, Song JH, Ko KS, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus infections in non-neutropenic cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:483–488. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espersen F, Frimodt-Moller N, Rosdahl VT, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients with hematological malignancies and/or agranulocytosis. Acta Med Scand. 1987;222:465–470. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1987.tb10966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Barca E, Carratala J, Mykietiuk A, et al. Predisposing factors and outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in neutropenic patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:117–119. doi: 10.1007/pl00011241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skov R, Gottschau A, Skinhoj P, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A 14-year nationwide study in hematological patients with malignant disease or agranulocytosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:563–568. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuervo SI, Cortes JA, Sanchez R, et al. Risk factors for mortality caused by Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in cancer patients. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2010;28:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mermel LA, Allon MA, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45. doi: 10.1086/599376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kullar R, Davis SL, Levine DP, et al. Impact of vancomycin exposure on outcomes in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Support for consensus guidelines suggested targets. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:975–981. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubin AS, Snydman DR, Ruthazer R, et al. Predicting high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:997–1002. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lodise TP, Graves J, Evans A, et al. Relationship between vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3315–3320. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00113-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musta AC, Riederer K, Shemes S, et al. Vancomycin MIC plus heteroresistance and outcome of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Trends over 11 years. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1640–1644. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02135-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soriano A, Marco F, Martinez JA, et al. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:193–200. doi: 10.1086/524667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takesue Y, Nakajima K, Takahashi Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration of 2 μg/mL methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients with bacteremia. J Infect Chemother. 2010;17:52–57. doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campo M, Hachem R, Jiang Y, et al. Panton valentine leukocidin exotoxin has no effect on the outcome of cancer patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:312–318. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31822d8978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes NE, Turnidge JD, Munckhof WJ, et al. Antibiotic choice may not explain poorer outcomes in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:340–347. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holland TL, Fowler VGJ. Vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration and outcome in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Pearl or pellet? J Infect Dis. 2011;204:329–331. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gould IM, Cauda R, Esposito S, et al. Management of serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: What are the limits? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lefebvre M, Jacqueline C, Amador G, et al. Efficacy of daptomycin combined with rifampicin for the treatment of experimental methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) acute osteomyelitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36:542–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrigos C, Murillo O, Euba G, et al. Efficacy of usual and high doses of daptomycin in combination with rifampin versus alternative therapies in experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother B. 2010;54:5251–5256. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00226-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moschovi M, Trimis G, Tsotra M, et al. Efficacy and safety of linezolid in immunocompromised children with cancer. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:694–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis T, Chaudhry R, Nightingale P, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Epidemiology, outcome, and laboratory characteristics in a tertiary referral center in the UK. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e131–e135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arbeit RD, Maki D, Tally FP, et al. The safety and efficacy of daptomycin for the treatment of complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1673–1681. doi: 10.1086/420818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]