Abstract

Fruit tissues of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) contain both photosynthetic and heterotrophic ferredoxin (FdA and FdE, respectively) isoproteins, irrespective of their photosynthetic competence, but we did not previously determine whether these proteins were colocalized in the same plastids. In isolated fruit chloroplasts and chromoplasts, both FdA and FdE were detected by immunoblotting. Colocalization of FdA and FdE in the same plastids was demonstrated using double-staining immunofluorescence microscopy. We also found that FdA and FdE were colocalized in fruit chloroplasts and chloroamyloplasts irrespective of sink status of the plastid. Immunoelectron microscopy demonstrated that FdA and FdE were randomly distributed within the plastid stroma. To investigate the significance of the heterotrophic Fd in fruit plastids, Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) activity was measured in isolated fruit and leaf plastids. Fruit chloroplasts and chromoplasts showed much higher G6PDH activity than did leaf chloroplasts, suggesting that high G6PDH activity is linked with FdE to maintain nonphotosynthetic production of reducing power. This result suggested that, despite their morphological resemblance, fruit chloroplasts are functionally different from their leaf counterparts.

Plastids play crucial roles in maintaining the life of plants by assimilating carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Such assimilation processes require reducing power, and plastids have developed two pathways to fulfill this need. The first is a light-dependent production of NADPH by the photosynthetic electron transport chain, and the second involves a light-independent production of NADPH by the enzymatic activities of G6PDH and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase of the OPP.

Fd occupies a branch point in this flow of electrons to produce or consume this reducing power. In photosynthetic plastids Fd accepts electrons from PSI and donates them for NADP+ reduction by FNR. On the other hand, in nonphotosynthetic plastids Fd works in the reverse direction of electron transfer. Here, electrons are accepted from NADPH produced by the OPP via FNR and then serve as reducing power for Fd-dependent enzymes. NADPH production by the OPP and the FNR-Fd electron-transfer system have been shown to be important in maintaining the activities of nitrite reductase and Fd-dependent glutamate synthase in root plastids (Bowsher et al., 1992).

Leaf and root plastids contain distinct Fd isoforms, a fact based on comparative studies of leaves and roots (Wada et al., 1986; Morigasaki et al., 1990). The differences were further confirmed by analysis of their primary structure and antigenicity. In addition, leaf and root Fd isoproteins exhibited different electron-transfer efficiencies. The rate of light-dependent NADPH production was higher using leaf Fd, whereas electron transfer from NADPH to Cyt c via FNR/Fd was more efficient using root Fd (Suzuki et al., 1985; Hase et al., 1991). These studies demonstrated that the leaf Fd is efficient in donating electrons to NADP+ and the root Fd is efficient in accepting electrons from NADPH. Thus, higher plants use two types of Fd isoproteins to optimize the utilization of the reducing power. Accordingly, leaf and root Fd isoproteins are convenient markers for NADPH-producing and -consuming functions of the plastid, respectively.

Fruits are of interest with respect to Fd isoprotein distribution and function because they have photosynthetic and light-independent sugar-storage capabilities. Previously, we established that fruit tissues of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) contained both leaf-type Fds and a root-type Fd, irrespective of photosynthetic competence (Aoki and Wada, 1996). Accumulation of the leaf-type Fds, FdA and FdC, were controlled by light, whereas light had no effect on the accumulation of the root-type Fd, FdE. In addition, the FNR-dependent Cyt c reduction efficiency with FdE was twice that with FdA. The distribution of these Fd isoforms within the green fruit displayed specific temporal and spatial patterns; the FdE/FdA ratio was higher in the later stages of fruit growth, as well as in the inner part of fruit where numerous starch granules developed. Because the tomato fruits contain fruit-specific isoproteins (FdB and FdD), leaf-type Fds and FdB were collectively referred to as the photosynthetic Fds, and root-type Fd and FdD were referred to as the heterotrophic Fds.

The coexistence of both types of Fd has also been reported in young leaves of maize seedlings (Kimata and Hase, 1989). In addition to Fd, the coexistence of leaf- and root-type FNR has been reported in the first foliage leaves of mung bean seedlings (Jin et al., 1994). However, the respective patterns of localization within these tissues have yet to be elucidated. These studies provide support for the following hypotheses for subcellular Fd localization. In the first model, the photosynthetic and heterotrophic isoproteins are thought to be present in the same plastid. In the second model, the plastids are differentiated into leaf-type chloroplasts and root-type heterotrophic plastids, which separately contain photosynthetic and heterotrophic Fds, respectively. To test these two models, it will be necessary to monitor the accumulation of Fd isoproteins in individual plastids.

In the present study we demonstrate immunocytochemical detection of photosynthetic and heterotrophic Fd isoproteins in fruit plastids. Immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy localized both Fds within identical plastids of green fruit tissues. A functional difference between leaf chloroplast and fruit plastids was also demonstrated with respect to nonphotosynthetic NADPH production. These results suggest that plastid development and the differential accumulation of Fd isoproteins are closely coupled.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv Momotaro) plants were grown in the greenhouse under natural light/dark conditions using a Hyponica hydroponic system (Kyowa, Osaka, Japan). Tomato fruits were grown in the dark essentially as described by Cheung et al. (1993) by wrapping the fruit in two layers of paper bags with black linings. The rest of the plant body was grown normally as described above.

Immature green fruit, fully expanded green fruit (mature green), fruit displaying the first visible red sign (breaker), fruit in which the red area was spreading (turning), and fruit in which the entire surface was red (red ripe) were used in the present study.

Antibodies

Anti-FdA mouse antiserum was prepared by Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Anti-FdA rabbit antiserum and anti-FdE rabbit antiserum were prepared by Bio Chiba (Watsuka, Kyoto, Japan). For each immunization, 1 mg of purified Fd isoprotein was used. Antibodies (immunoglobulins) were pelleted by adding ammonium sulfate to the antisera to 55% saturation, and resuspended in PBS (10 mm sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.2] and 150 mm NaCl). Further purification of antibodies was carried out using Fd-loaded cyanogen bromide-Sepharose 4B columns (Pharmacia).

Isolation of Intact Plastids

Leaf and fruit chloroplasts were isolated as described by Kinoshita and Tsuji (1984), with all procedures performed at 4°C. Fresh leaves and green fruits were homogenized with extraction medium (330 mm sorbitol, 30 mm Mops-NaOH [pH 7.8], 2 mm EDTA, and 0.2% BSA). After the filtered homogenate was centrifuged, chloroplast pellets were further purified on a Percoll step gradient (Pharmacia). The three-step gradient contained 90%, 40%, and 20% (v/v) Percoll in pH 7.4 extraction medium. Chloroplast suspensions were layered on top of the gradient and centrifuged at 3500g for 20 min. Intact chloroplasts that banded at the 40%/90% interface were removed, diluted with extraction medium, and pelleted at 2200g for 1 min.

Fruit chromoplasts were isolated essentially as described by Bathgate et al. (1985). The pericarp and columella of red tomato fruits were sliced and homogenized with chromoplast extraction medium (400 mm Suc, 100 mm Tris-HCl [pH 8.2], 2 mm MgCl2, 8 mm EDTA, 10 mm KCl, and 4 mm Cys). The filtered homogenate was centrifuged at 5,000g for 5 min. The chromoplast pellet was further purified as described by Leidvogel (1987). The pellet was resuspended in a medium containing 50% (w/v) Suc, 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 2 mm MgCl2, 8 mm EDTA, 10 mm KCl, and 4 mm Cys. The suspension was then placed into centrifugation tubes to form a layer at the bottom of a discontinuous gradient containing 40%, 30%, and 15% (w/v) Suc dissolved in a solution of 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 2 mm MgCl2, 8 mm EDTA, 10 mm KCl, and 4 mm Cys, and centrifuged at 74,000gmax for 1 h. Intact chromoplasts concentrated by flotation at the 30%/40% interface were diluted with extraction medium and pelleted at 5,000g for 5 min.

To obtain soluble, plastidic proteins, intact plastid fractions were osmotically ruptured by 20-fold dilution with 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and centrifuged at 27,000g for 5 min. The supernatant was fractionated by addition of ammonium sulfate to 70% saturation, and the resultant supernatant was dialyzed against 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and concentrated by using Centriprep-3 and Microcon-3 columns (Amicon).

Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

Nondenaturing PAGE was carried out using a 15% polyacrylamide gel according to the method of William and Reisfeld (1964). Proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane as previously described (Aoki and Wada, 1996). Visualization of the immunoreaction was carried out by using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham) or catalyzed signal amplification system (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Tomato plant tissues were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). After dehydration in a graded-ethanol series, tissues were embedded in Technovit 8100 (Heraeus Kulzer GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Semi-thin sections were mounted on 233-kD poly-l-Lys-coated glass slides (Sigma). Sections were treated with blocking solution S (10% [v/v] normal swine serum [Dako] in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, prior to being incubated overnight at room temperature with a cocktail of anti-FdA mouse and anti-FdE rabbit antibodies diluted 1:50 in blocking solution S. Sections were then incubated for 1 h in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:200 in blocking solution S. After the sections were washed with PBS, immunoreactions for FdA and FdE were visualized by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (diluted 1:20 in blocking solution S, Dako) and by TRITC-conjugated streptavidin (diluted 1:200 in blocking solution S, Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL), respectively. The sections were counterstained with 1 μg/mL DAPI (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) in TAN buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.5 mm EDTA, 1.2 mm spermidine, and 0.05% [v/v] 2-mercaptoethanol; Fujie et al., 1994). Stained samples were observed under an Olympus BX50 fluorescence microscope.

Electron Microscopy

For conventional electron microscopy, tomato plant tissues were fixed overnight with 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde, postfixed with 0.5% (v/v) OsO4 for 20 min, stained with 0.5% (w/v) uranium acetate for 30 min, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in an epoxy resin based on Glicidether 100 (Selva Feinbiochemica GmbH & Co., Heidelberg, Germany).

For postembedding immunoelectron microscopy, tomato plant tissues were fixed overnight with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), dehydrated in a graded-ethanol series, and embedded in London Resin White (hard grade, London Resin Co., London, UK) in the presence of 1% (w/w) benzoyl peroxide. London Resin White was then polymerized for 1 to 2 d at room temperature by using a UV polymerizer. Ultrathin sections cut from the London Resin White block were incubated with blocking solution M (10% [v/v] normal mouse serum [Dako] in PBS) for 30 min and incubated with anti-FdA rabbit antibody or with anti-FdE rabbit antibody diluted 1:20 in blocking solution M overnight at 4°C. After the sections were washed with PBS, immunoreaction sites were labeled with 10-nm gold particle-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (British BioCell International, Cardiff, UK) diluted 1:33 in blocking solution M for 2 h at room temperature. The ultrathin sections were then stained with 0.5% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 20 min.

For pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy, tissue blocks were cryoprotected by overnight immersion in a 30% (w/v) Suc solution dissolved in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) held at 4°C and then frozen and cut into 15-μm sections using a cryostat. Sections were mounted on poly-l-Lys-coated glass slides, incubated with blocking solution M for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated with anti-FdA rabbit antibody or anti-FdE rabbit antibody (both diluted 1:50 in blocking solution M) overnight at room temperature. Immunoreaction sites were visualized by incubating the sections successively with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody diluted 1:200 in blocking solution M for 1 h, streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Dako) diluted 1:300 in PBS for 1 h, and finally a mixture of 0.01% (w/v) 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and 0.02% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Immunostained cryosections were postfixed with 0.5% (v/v) OsO4 for 20 min, stained with 0.5% (w/v) uranium acetate for 30 min, dehydrated in a graded-ethanol series, and embedded in an epoxy resin based on Glicidether 100 (Selva Feinbiochemica GmbH & Co).

Ultrathin sections were examined using a Hitachi H-700 electron microscope operated at 100 kV. For quantitative analysis of the results of postembedding immunogold labeling, the area of cellular compartments on the electron micrographs was measured by using Lia32 for Windows 95, version 0.36 (free software developed by Dr. K. Yamamoto; for information, see http://www.agr.niigata-u.ac.jp/∼kazukiyo/lia32.html).

Assay of Plastidic G6PDH Activity

G6PDH activity was measured essentially as described by Graeve et al. (1994) with minor modifications. The plastids were ruptured osmotically by dilution of the suspension (1:30 in 100 mm Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]), centrifuged at 27,000g for 10 min, and the supernatant containing stromal proteins was preincubated in the presence or absence of 20 mm DTT at 4°C for 10 min under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 white light to mimic the light conditions in the greenhouse. G6PDH activity was assayed at 20°C by measuring the A340 in a reaction mixture containing 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 0.2 mm NADP+, 2 mm Glc6P, and 5 mm MgCl2, with or without 20 mm DTT. The number of plastids in suspensions was counted on a hemocytometer after proper dilution.

RESULTS

Fd Isoproteins in Isolated Fruit Plastids

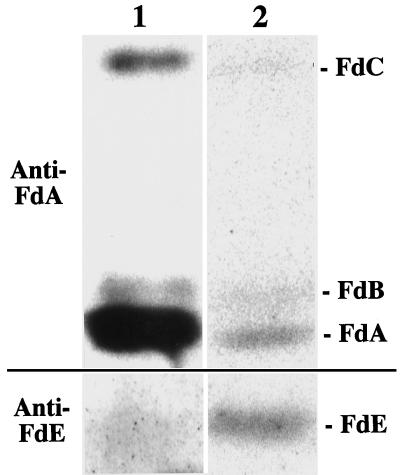

To determine the Fd isoprotein profiles in fruit plastids, intact chloroplasts and chromoplasts were isolated from mature green and red-ripe fruits, respectively, and soluble protein fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using polyclonal antibodies against the photosynthetic FdA and the heterotrophic FdE (Fig. 1). Only a small amount of soluble protein was obtained from the chloroplast fraction because of the low recovery of intact fruit chloroplast (about 80% intact), which made the detection of Fds difficult. To overcome this problem, the immunoreaction was visualized by using the tyramide-amplified horseradish peroxidase detection system originally developed for immunocytochemistry. FdA, FdB, and FdC were clearly detected, and FdE was faintly detected in the chloroplast fraction. In the isolated chromoplast fraction (about 75% intact), FdA, FdB, FdC, and FdE were clearly detected by chemiluminescence. The relative amount of FdA in the chromoplast fraction was smaller than that in the chloroplast fraction.

Figure 1.

Immunoblot analysis of Fd profiles in isolated fruit chloroplasts (lane 1) and chromoplasts (lane 2). Lanes 1 and 2 contain 5 and 20 μg of soluble plastidic protein, respectively. Immunoreaction was visualized by using catalyzed signal amplification system reagents in lane 1 and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents in lane 2.

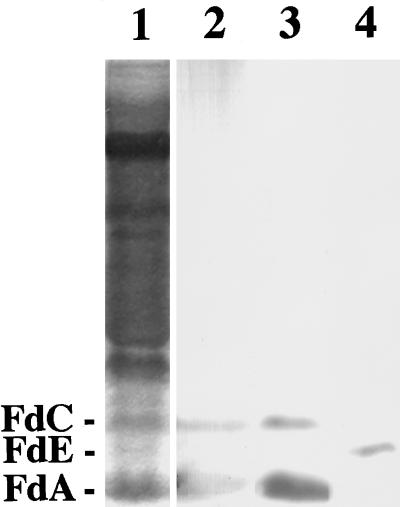

Specificity of Anti-Fd Antibodies

To determine whether there was a plastid-by-plastid difference in the Fd profile, we carried out immunocytochemical analyses. Mouse polyclonal antiserum against FdA and rabbit polyclonal antiserum against FdA and FdE were purified with FdA- and FdE-loaded affinity columns, respectively, to obtain highly specific antibodies (Fig. 2). It should be stressed that no cross-reaction was seen between anti-FdA and anti-FdE antibodies. Cross-reactivity of anti-FdA antibodies to FdC could not be completely abolished. However, this antibody could be used for the detection of photosynthetic isoproteins, because the accumulation patterns of FdA and FdC have been shown to be similar (Aoki and Wada, 1996).

Figure 2.

Specificity of antibodies used for immunocytochemical analyses. Lane 1, Coomassie brilliant blue-stained proteins after nondenaturing PAGE. Proteins shown in lane 1 were blotted onto a PVDF membrane and subjected to immunodetection by using anti-FdA mouse antibody (lane 2), anti-FdA rabbit antibody (lane 3), and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (lane 4). Each lane contained 20 μg of soluble protein extracted from red-ripe fruits. The immunoreaction was visualized by using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents.

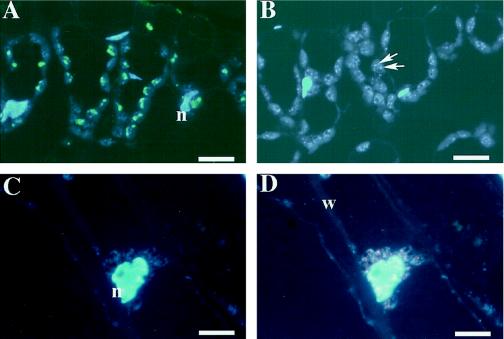

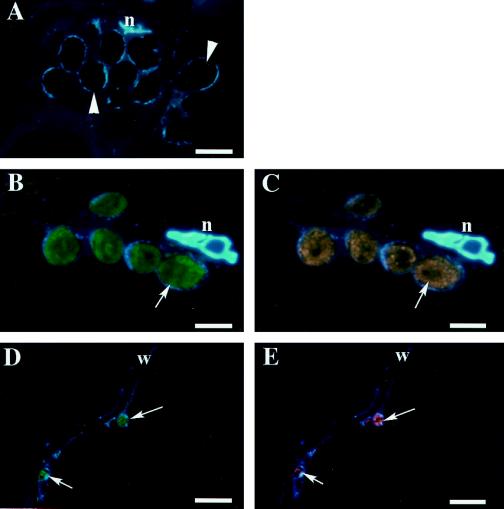

Immunoreactivity associated with both antibodies was localized in plastids, which almost disappeared by using preimmune IgGs and antibodies preincubated with the antigens (data not shown). The specificity of the antibodies was tested further by applying them to leaf and root sections. Tissues were embedded in a hydrophilic resin and cut into 1-μm-thick sections. Immunoreactivity for FdA and FdE was visualized by FITC and TRITC, respectively. Sections were counterstained with DAPI to localize DNA-containing organelles. Leaf chloroplasts were FITC labeled for FdA but were not TRITC labeled for FdE (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, root plastids were TRITC labeled for FdE but were not FITC labeled for FdA (Fig. 3, C and D). This result is consistent with previous results of immunoblotting where it was shown that leaf tissues contain FdA but no FdE, and that root tissues contain FdE but no FdA (Aoki and Wada, 1996). Therefore, we conclude that the immunoreaction of anti-FdA and anti-FdE antibodies is specific to their antigens.

Figure 3.

Localization of FdA and FdE in leaves and roots. Leaf (A and B) and root (C and D) sections were labeled with anti-FdA mouse antibody (A and C) and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (B and D). Immunoreactions were visualized by fluorescence of FITC (green) for FdA and TRITC (red) for FdE. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Arrows in B indicate punctate ctDNA (nucleoid). n, Nucleus; w, cell wall. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Localization of Fd Isoproteins in Fruit Tissues by Immunofluorescence Microscopy

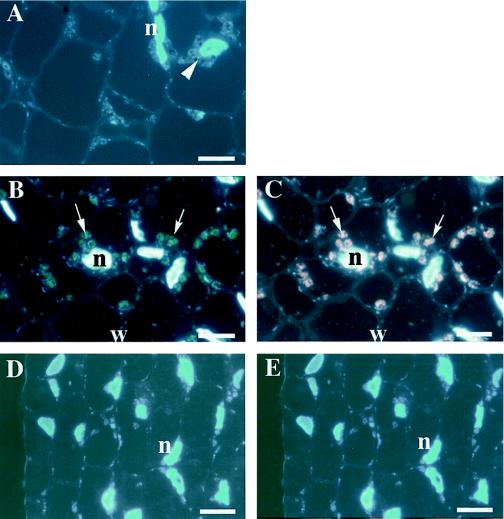

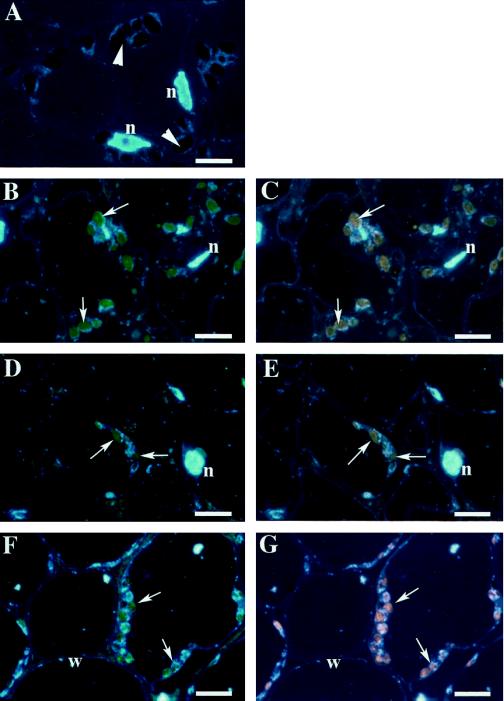

Double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy was performed by using sections of green fruit tissues to determine whether FdA and FdE were localized in identical or separate plastids. In most plastids displaying immunofluorescence, overlapping signals for FdA and FdE were detected (Figs. 4–6). This result clearly demonstrated that FdA and FdE were colocalized in the same fruit plastids.

Figure 4.

Localization of FdA and FdE in preanthesis tomato fruit by double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy. As a control, the columella was double labeled with preimmune IgGs of mouse and rabbit (A). The plastid position is indicated by an arrowhead. The columella (B and C) and the mesocarp (D and E) were double labeled with anti-FdA mouse antibody (B and D) and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (C and E). The positions of immunolabeled plastids are indicated by arrows. Visualizations are the same as in Figure 4. n, Nucleus; w, cell wall. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Figure 6.

Localization of FdA and FdE in 23-mm-diameter fruit by double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy. As a control, the inner mesocarp was double labeled with preimmune IgGs of mouse and rabbit (A). The plastid positions are indicated by arrowheads. The inner mesocarp (B and C) and the outer mesocarp (D and E) were double labeled with anti-FdA mouse antibody (B and D) and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (C and E). The positions of immunolabeled plastids are indicated by arrows. Visualizations are the same as in Figure 4. n, Nucleus; w, cell wall. Scale bars = 5 μm.

The cellular/tissue localization of Fds was examined next. The fruit was divided into four parts: the outer mesocarp, the inner mesocarp, the vascular bundle, which is a boundary of the outer and the inner mesocarp, and the columella. Fds first appeared in plastids of the columella in the fruit before anthesis, whereas Fds were not detected in plastids of the mesocarp at this stage (Fig. 4). In the fruit just after anthesis (5 mm diameter), Fds were detected in some of the plastids of the inner mesocarp near the basal end of the fruit, as well as in the columella plastids (data not shown). In 11-mm-diameter fruit, Fd-labeled plastids could be found both in the outer and the inner mesocarp (Fig. 5). Plastids in the inner mesocarp and the columella were larger than those in the outer mesocarp, suggesting that plastid enlargement progressed faster in the inner part of the fruit. In 23-mm-diameter fruit, the plastids in the inner mesocarp were extensively expanded because of the presence of large starch granules, whereas only a few plastids in the outer mesocarp contained starch granules. Plastids in the inner mesocarp were intensely labeled for FdA and FdE. In contrast, only a few Fd-labeled plastids were found in the outer mesocarp (Fig. 6). It should be noted that FdA and FdE were not detected in the vascular tissue at any stage of fruit development.

Figure 5.

Localization of FdA and FdE in 11-mm-diameter fruit by double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy. As a control, the columella was double labeled with preimmune IgGs of mouse and rabbit (A). The plastid positions are indicated by arrowheads. The columella (B and C), the inner mesocarp (D and E), and the outer mesocarp (F and G) were double labeled with anti-FdA mouse antibody (B, D, and F) and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (C, E, and G). The positions of immunolabeled plastids are indicated by arrows. Visualizations are the same as in Figure 4. n, Nucleus; w, cell wall. Scale bars = 5 μm.

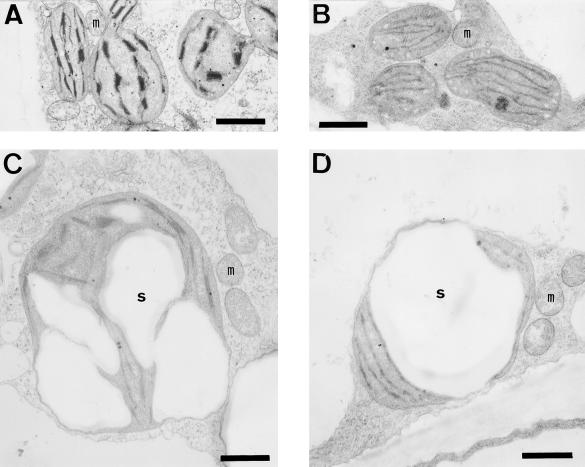

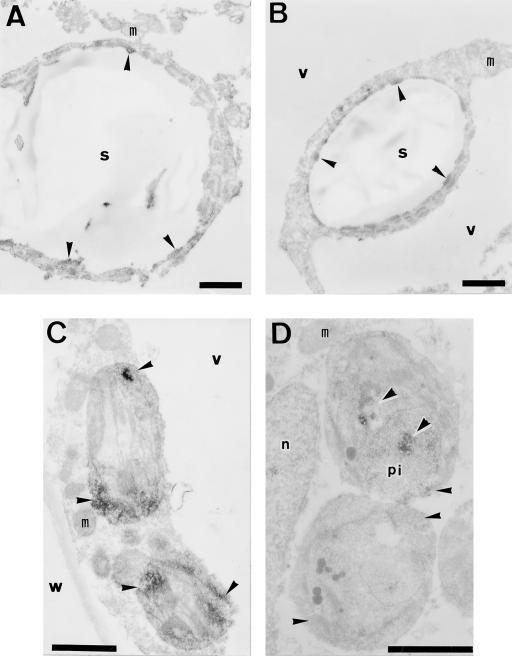

Plastids in the green fruit tissues of tomato could be classified into two types on the basis of the sink status. Although their distribution appears to have tissue-specific patterns, they were found in the same cell at times. In one type, the plastids contained no starch granule but had stacked thylakoid membranes, hereafter referred to as “fruit chloroplast” (Fig. 7A). Fruit chloroplasts were found in the columella and the mesocarp prior to anthesis, in the mesocarp of 11-mm-diameter fruits, and in the outer mesocarp of 23-mm-diameter fruits. The second plastid type contained large starch granules and the stacked thylakoid membranes were appressed to the plastid envelope, hereafter referred to as “chloroamyloplast” (Fig. 7B). Chloroamyloplasts were found in the columella and the mesocarp of 11-mm-diameter fruits and in the inner and the outer mesocarp of 23-mm-diameter fruits. Thylakoid membranes of chloroamyloplasts became unstacked with dark treatment (Fig. 7, C and D), but the amount of starch did not change significantly (Fig. 7D). Thus, it is likely that starch in the chloroamyloplast is not transient starch accompanied by photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the fruit, but storage starch resulting from deposition of sugars transported from leaves. As shown in Figures 4–6, both types of fruit plastids contain FdA and FdE.

Figure 7.

Ultrastructures of plastids in light-grown (A and C) and dark-grown (B and D) fruit. Two morphologically different plastids were found: plastids that contain few starch granules (A and B; fruit chloroplasts) and plastids that contain large starch granules (C and D; chloroamyloplasts). m, Mitochondria; s, starch granule. Scale bars = 1 μm.

It is interesting that in the fruit chloroplasts of the columella before and just after anthesis, plastid DNAs were stained with DAPI as small punctate deposits. This structure was typical of chloroplasts within mature leaves (Fig. 4, A and B, and Fujie et al., 1994). Along with starch accumulation, fruit plastid DNAs lost this punctate-like appearance and were transformed into ring-like structures typically seen in chloroamyloplasts of 11- and 23-mm-diameter fruits (Figs. 5 and 6).

In summary, our experiments established that FdA and FdE are colocalized in the same fruit chloroplasts and chloroamyloplasts. FdA and FdE first appeared in the columella and then spread out to the whole mesocarp. Finally, Fds accumulated mainly in the inner mesocarp and the columella, whereas they were scarcely found in the outer mesocarp. Accumulation of Fds appeared to increase with development of the chloroamyloplast. Fds were not detected in fruit chloroplasts of the mesocarp prior to anthesis in these studies, probably because the amount of Fds was below the detection limit of the methods used.

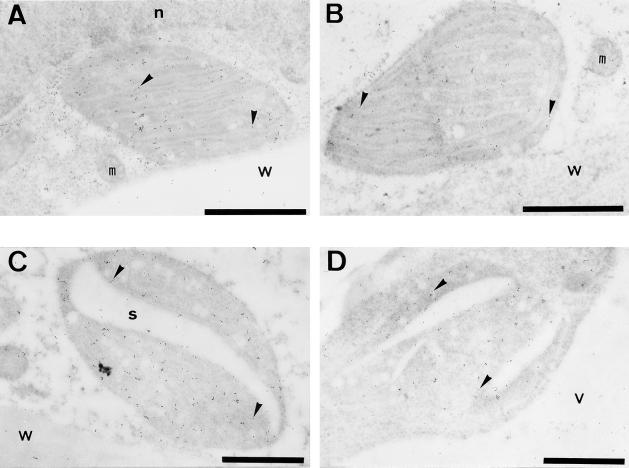

Localization of Fd Isoproteins by Immunoelectron Microscopy

Immunoelectron microscopy was performed to investigate the distribution of Fds within the plastid. Immunogold label for FdA and FdE was clearly detected in the fruit chloroplasts (Fig. 8). To confirm the specific localization of Fds in the fruit chloroplasts, we estimated labeling densities of the gold particles in cellular compartments. When anti-FdA antibody was used (n = 1559), the labeling density was 36.2 (gold particles)/μm2 in the fruit chloroplasts, 4.3/μm2 in the mitochondria, 3.0/μm2 in the cytosol, 3.1/μm2 in the vacuole, 3.5/μm2 in the cell wall, and 2.0/μm2 in the nucleus. Labeling density in the fruit chloroplast was 10 times as high as that in other cellular compartments. However, when anti-FdE antibody was used (n = 1036), the labeling density was 15.0/μm2 in the fruit chloroplast, 7.4/μm2 in the mitochondria, 2.7/μm2 in the cytosol, 3.1/μm2 in the vacuole, 3.3/μm2 in the cell wall, and 0.0/μm2 in the nucleus. Although labeling density in the mitochondria was high, labeling density in the fruit chloroplast was significantly higher than in all other cellular compartments. Therefore, we conclude that both FdA and FdE are localized in the fruit chloroplasts of the outer mesocarp. Gold particles labeled for FdA were found primarily in the stromal region and not in association with the thylakoid membranes. Similarly, FdE was found in the stromal region. These findings are fully consistent with the commonly accepted localization of Fd in the stroma of leaf chloroplasts.

Figure 8.

Localization of FdA and FdE in fruit plastids by immunogold electron microscopy. Fruit chloroplasts of 23-mm-diameter fruit (A and B) and the plastids undergoing transition from chloroplast to chromoplast of the turning fruit (C and D) were labeled with anti-FdA rabbit antibody (A and C) and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (B and D). The positions of the 10-nm gold particles are indicated by arrowheads. Gold particles were mostly found in the stroma. n, Nucleus; m, mitochondria; s, starch; v, vacuole; w, cell wall. Scale bars = 1 μm.

In addition to the plastids in the green fruit, the ultrastructure and the presence of Fds were investigated in the transitional plastids in the ripening fruit. In the outer mesocarp of the breaker fruit, the thylakoid structure within the plastids disappeared and starch granules were degraded (Fig. 8). In such plastids, FdA was localized not only in the stroma but also in the region of the starch granules. Although labeling density of the gold particles for FdA was lower in the latter region compared with the stroma, immunolabeling was specific compared with the labeling detected in the preimmune IgG control. Experiments performed using anti-FdE antibody revealed that the stroma and starch were also immunolabeled.

Since it was difficult to obtain intact, ultrathin sections of London Resin White-embedded chloroamyloplasts containing large starch granules, we performed horseradish peroxidase-labeling electron microscopy by the pre-embedding method (Fig. 9). Immunoreactivity for FdA was detected in the stromal region but not in the starch region of the chloroamyloplast. Similarly, immunoreactivity for FdE was detected selectively in the stromal region of the chloroamyloplast. The pre-embedding method was also applied to fruit chloroplasts in the columella just after anthesis. Immunoreactivity for FdA and FdE was mostly detected in the stroma and the periphery of the thylakoid membranes. At this stage, most fruit plastids in the columella contained electron-dense proteinaceous inclusions bounded by a single membrane. Immunoreactivity for both Fds was often found within such proteinaceous inclusions.

Figure 9.

Localization of FdA and FdE in fruit plastids by immunoperoxidase electron microscopy. Chloroamyloplasts of 23-mm-diameter fruit (A and B) and fruit chloroplasts in the columella of preanthesis fruit (C and D) were labeled with anti-FdA rabbit antibody (A and C) and anti-FdE rabbit antibody (B and D). The immunoreaction was visualized by diaminobenzidine stain, and the positions of the immunoreaction sites are indicated by arrowheads. Immunoreactivity was mostly found in the stroma and on occasion in the proteinaceous inclusion body. n, Nucleus; m, mitochondria; pi, proteinaceous inclusion body; s, starch granule; v, vacuole; w, cell wall. Scale bars = 1 μm.

Activity of Plastidic G6PDH Was Higher in Fruit Plastids than in Leaf Chloroplasts

The heterotrophic Fd isoprotein plays a crucial role in electron transfer from NADPH to the Fd-dependent enzymes, particularly in the nonphotosynthetic plastids (Bowsher et al., 1992), in which NADPH is supplied by the activity of G6PDH of the OPP. Thus, characterization of plastidic activities related to Glc6P metabolism provided insight into the role of the heterotrophic Fd isoprotein in the fruit plastid. It was reported that the phosphate translocator of fruit chloroplasts was capable of transporting not only triose phosphates but also Glc6P (Schunemann and Borchert, 1994). To determine whether fruit plastids maintain nonphotosynthetic NADPH production, we compared the activity of G6PDH in leaf chloroplasts, fruit chloroplasts, and fruit chromoplasts isolated from tissues harvested during the normal light period.

Although activity of the cytosolic marker enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the isolated plastid fraction was low, the plastidic G6PDH activity was estimated from the difference between measurements without and with DTT to exclude the possibility of contaminating cytosolic G6PDH activity (Johnson, 1972). G6PDH activity was estimated on the basis of plastid number. Plastidic G6PDH activity in the leaf chloroplast was low, whereas activities in the fruit chloroplast and chromoplast were 7 and 48 times higher, respectively, than that in the leaf chloroplast (Table I).

Table I.

Plastidic G6PDH activity in isolated plastids

| Plastid | G6PDH Activity |

|---|---|

| nmol min−1 10−9 plastids | |

| Leaf chloroplast | 0.56 ± 0.18 |

| Fruit chloroplast | 3.7 ± 0.10 |

| Fruit chromoplast | 27.3 ± 3.04 |

Plastidic G6PDH activity was calculated from the difference between the measurements with and without 20 mm DTT. Reduction of NADP+ was monitored. Values are the averages ±se of five determinations.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we present immunological evidence for the colocalization of photosynthetic and heterotrophic Fd isoproteins in tomato fruit plastids. First, immunoblotting studies established that FdA and FdE are present in the soluble protein fraction obtained from isolated fruit chloroplasts and chromoplasts (Fig. 1). However, this result did not exclude the possibility that the isolated plastid fraction was extracted from a mixture of two populations of plastids with a similar density, which separately contained FdA or FdE. However, double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy clearly demonstrated that FdA and FdE were colocalized in the same plastid (Figs. 4–6). Furthermore, FdA and FdE were also detected in fruit chloroplasts and chloroamyloplasts by gold-labeling and horseradish peroxidase-labeling electron microscopy (Figs. 8 and 9).

Immunoelectron microscopy demonstrated that both FdA and FdE were randomly localized in the stroma, i.e. there does not appear to be any particular association between these and any plastidic structure. In chloroamyloplasts the FITC and TRITC fluorescent signals were associated with the starch granules. In most of the chloroamyloplast cross-sections examined, this signal was brighter in the periphery of the starch granule and dimmer in the core. Thus, the distribution of fluorescence could be attributed in part to the thickness of the section and may not indicate the localization of Fds within starch granules. Concerning other plastidic structures, immunoreactivity was also found in the proteinaceous inclusion bodies of the fruit chloroplasts (Fig. 9, C and D) and in the deformed structure of the chromoplasts (Fig. 8, C and D). Membrane-bound proteinaceous inclusion bodies have been reported in the chloroplasts of several plant species, and Rubisco and phenoloxidase appear to be present in these bodies (for review, see Kirk and Tilney-Bassett, 1978). Although the origin and fate of these inclusion bodies have not been elucidated, we speculate that stromal proteins, including Fds, are concentrated in these inclusion bodies at the early stage of fruit-plastid development. The deformed structures of the chromoplasts are most likely degrading chloroamyloplast starch granules. We speculate that this starch-granule-like structure is not as “rigid” as the granules in the mature chloroamyloplasts and may contain stromal components, including Fds. Collectively, these results indicate that both photosynthetic and heterotrophic Fd isoproteins are localized in the stroma of the fruit plastids.

Two morphologically different plastids, the fruit chloroplast and the chloroamyloplast, were found in immature green fruit tissues. However, based on our immunocytochemical studies, these plastids are not qualitatively different in terms of their Fd profiles. The difference between the two types of plastids was in the extent of starch accumulation. Starch granules within chloroamyloplasts were abundant in the columella and the inner mesocarp. Wang et al. (1994) reported that the spatial distribution of starch granules and Suc synthase were similar, an observation quite consistent with our findings. It is most likely that the chloroamyloplasts represent the full-grown form of the fruit chloroplasts and that their growth depends on the cellular sugar concentration or sink strength. We speculate that the differentiation of fruit chloroplasts and chloroamyloplasts is not developmentally determined, because the chloroamyloplast formation was not restricted within the columella and the inner mesocarp. Formation of chloroamyloplasts at times appears to occur in the outer mesocarp tissue (Figs. 5 and 6). We noted that the starch granules, when formed in the outer mesocarp of the 11-mm-diameter fruit, disappeared in the 23-mm-diameter fruit (Fig. 6), suggesting that the fruit chloroplast and the chloroamyloplast are interchangeable in a given tissue. It also supports our speculation that the formation of the chloroamyloplast is not determined developmentally but is dependent stochastically on the sink status.

What is the significance of the heterotrophic Fd isoprotein in green fruit plastids? We expected that a comparison of the fruit plastids with the leaf chloroplast would provide insight into this question, because both are photosynthetically competent, but heterotrophic Fd isoprotein was present exclusively in the fruit plastids. G6PDH activity in the chloroplast and chromoplast of the fruit were 7 and 48 times as high, respectively, as that in the leaf chloroplast (Table I). The photosynthetic capability of the fruit plastids is relatively low (Piechulla et al., 1987). As a consequence, the higher G6PDH activity of the fruit plastids implies that the inhibitory effect of photosynthetically reduced thioredoxin on G6PDH is low. Therefore, it seems logical that in the less-photosynthetic fruit plastids the higher plastidic G6PDH activity is required for NADPH production, and NADPH is preferentially consumed by the heterotrophic Fd isoprotein in the Fd-dependent metabolic pathway (except for futile production of NADPH).

The phosphate translocator of the fruit plastid is capable of translocating Glc6P (Schunemann and Borchert, 1994). We obtained results consistent with this study by measuring the inhibitory effect of Glc6P on the Pi translocation (K. Aoki and K. Wada, unpublished results). Imported Glc6P is first stored as starch and later can be remobilized as a substrate for G6PDH in the OPP (Thom and Neuhaus, 1995). Thus, the high activity of the plastidic G6PDH would be advantageous under Glc6P-rich conditions in producing light-independent reducing power, and, consequently, the presence of the heterotrophic Fd should be advantageous for utilizing the produced light-independent reducing power. However, it should be mentioned that an increase in G6PDH activity may not be attributed only to the release from photosynthetic inactivation but also to the increase in the amount of G6PDH protein, although the level was not estimated. Finally, the nature of the preferred electron-accepting partner for the heterotrophic Fd remains to be identified.

Both fruits and leaves develop from the shoot apical meristem and possess chlorophyll-containing plastids. However, the established differences in the Fd profile and in G6PDH activity demonstrate that plastids within fruits and leaves differ with respect to their production/ consumption of NADPH. In other words, fruit chlorophyll-containing plastids are distinct from leaf chloroplasts. The presence of FdE and the high activity of G6PDH, together with the capacity to translocate Glc6P, suggest that fruit plastids utilize imported sugar phosphate for their source of reducing power. Accumulation of FdE in the very early stage of fruit development (fruit before anthesis) implies that the functional differentiation between fruit and leaf plastids occurs concomitantly with organ differentiation.

Based on these observations, it would appear that the accumulation of Fd isoproteins is primarily controlled in an organ-dependent manner. This hypothesis would explain the colocalization of FdA and FdE in fruit plastids with varying photosynthetic and sink status. However, the quantitative differences between the accumulation patterns of Fd isoproteins cannot be overlooked. For example, the photosynthetic isoproteins are more abundant in light-grown than in dark-grown fruits, and the heterotrophic isoprotein is more abundant in the inner part of the fruit, where numerous chloroamyloplasts have been found (Aoki and Wada, 1996). Thus, the accumulation patterns of Fds must undergo fine modulation by environmental and nutritional factors within the limit of organ-dependent control.

The accumulation of FdE may also be controlled by sugars, because the presence of this isoprotein was positively correlated with the pattern of starch accumulation. To ascertain the influence of metabolic control (by sugar) over FdE level, we attempted to analyze FdE in detached leaves fed with exogenous Suc. Unfortunately, we were not able to detect FdE in these leaves; rather, an increase in the level of an unidentified Fd isoprotein was observed (data not shown). This preliminary result indicates that FdE accumulation is not induced in leaves by exogenous Suc treatment, suggesting that metabolic control does not override organ-dependent control of Fd accumulation. It will be important to elucidate the mechanisms that control the expression and accumulation of Fd isoproteins, which will bridge the gap between plastid development and organ differentiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Mitsuharu Satoh (Bio Chiba, Kyoto, Japan) for producing antibodies, Dr. Yutaka Yada (Ishikawa Forest Experiment Station, Tsurugi, Ishikawa, Japan) and Dr. Kazukiyo Yamamoto (Niigata University) for Lia32, and Mr. Shuichi Yamazaki (Department of Anatomy 1, School of Medicine, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan) for photographic assistance. We would also like to thank Dr. W.J. Lucas (The University of California, Section of Plant Biology, Division of Biological Science) for reading the manuscript and improving the English.

Abbreviations:

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FNR

Fd-NADP+ oxidoreductase

- G6PDH

Glc 6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Glc6P

Glc 6-phosphate

- OPP

oxidative pentose phosphate pathway

- TRITC

tetramethyl-rhodamine B isothiocyanate

Footnotes

This work was supported by research fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists to K.A. and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports, Japan, to K.W. (no. 05454016).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aoki K, Wada K. Temporal and spatial distribution of ferredoxin isoproteins in tomato fruit. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:651–657. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate B, Purton ME, Grierson D, Goodenough PW. Plastid changes during the conversion of chloroplasts to chromoplasts in ripening tomatoes. Planta. 1985;165:197–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00395042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowsher CG, Boulton EL, Rose J, Nayagam S, Emes MJ. Reductant for glutamate synthase is generated by the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway in non-photosynthetic root plastids. Plant J. 1992;2:893–898. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AY, McNellis T, Piekos B. Maintenance of chloroplast components during chromoplast differentiation in the tomato mutant Green Flesh. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:1223–1229. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.4.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujie M, Kuroiwa H, Kawano S, Mutoh S, Kuroiwa T. Behavior of organelles and their nucleoids in the shoot apical meristem during leaf development in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Planta. 1994;194:395–405. doi: 10.1007/BF00194444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeve K, von Schaewen A, Scheibe R. Purification, characterization, and cDNA sequence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Plant J. 1994;5:353–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1994.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase T, Mizutani S, Mukohata Y. Expression of maize ferredoxin cDNA in Escherichia coli. Comparison of photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic ferredoxin isoproteins and their chimeric molecule. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1395–1401. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Morigasaki S, Wada K. Purification and characterization of two ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase isoforms from the first foliage leaves of mung bean (Vigna radiata) seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:697–702. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.2.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HS. Dithiothreitol: an inhibitor of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in leaf extracts and isolated chloroplasts. Planta. 1972;106:273–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00388105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Hase T. Localization of ferredoxin isoproteins in mesophyll and bundle sheath cells in maize leaf. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:1193–1197. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita I, Tsuji H. Benzyladenine-induced increase in DNA content per chloroplast in intact bean leaves. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:575–578. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.3.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk JTO, Tilney-Bassett RAE (1978) Chloroplasts of vascular plants. In The Plastid: Their Chemistry, Structure, Growth and Inheritance, Ed 2. Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp 127–134

- Leidvogel B. Isolation of membranous chromoplasts from daffodil flowers. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Morigasaki S, Takata K, Sanada Y, Wada K, Yee BC, Shin S, Buchanan BB. Novel forms of ferredoxin and ferredoxin-NADP reductase from spinach roots. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;283:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechulla B, Glick RE, Bahl H, Melis A, Gruissem W. Changes in photosynthetic capacity and photosynthetic protein pattern during tomato fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:911–917. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.3.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunemann D, Borchert S. Specific transport of inorganic phosphate and C3- and C6-sugar-phosphate across the envelope membranes of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) leaf-chloroplasts, tomato fruit-chloroplasts and fruit-chromoplasts. Bot Acta. 1994;107:461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Oaks A, Jacquot JP, Vidal J, Gadal P. An electron transport system in maize roots for reaction of glutamate synthase and nitrite reductase. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:374–378. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.2.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom E, Neuhaus E. Oxidation of imported or endogenous carbohydrates by isolated chloroplasts from green pepper fruits. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1421–1426. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Onda M, Matsubara H. Ferredoxin isolated from plant non-photosynthetic tissues. Purification and characterization. Plant Cell Physiol. 1986;27:407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Smith A, Brenner ML. Temporal and spatial expression pattern of sucrose synthase during tomato fruit development. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:535–540. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- William DE, Reisfeld RA. Disk electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gel. Extension to new conditions of pH and buffers. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1964;121:372–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb14210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]